Abstract

Peer to peer (P2P) support has been suggested as one community program that may promote aging in place. We sought to understand challenges older adults have maintaining their independence and to identify how P2P support facilitates independence. We completed 17 semi-structured interviews with older adults receiving P2P support in 3 cities in the United States. Study team members coded data using deductive and inductive conventional content analysis. Participants identified declining abilities, difficulties with mobility, and increasing cost of living as challenges to independence. P2P support facilitated independence and provided them with a new friend. The qualitative findings indicate that maintaining independence as an older adult in the United States has many challenges. P2P programs have an important role in helping older adults stay in their home by supporting mobility and promoting social engagement.

Keywords: Independence, peer-to-peer support, aging in place, isolation, transportation, cost of living

INTRODUCTION

In 2030 the United States (US) Census Bureau projects that there will be 72 million people 65 and older living in the US, accounting for over 20 percent of the total US population.1 Most people age 65 and older report their health as good, very good, or excellent, but with age comes increased risk of certain diseases and disorders.2 These health conditions and the process of aging itself frequently lead to functional decline in older Americans. In 2013, about 44 percent of people age 65 and older enrolled in Medicare reported a functional limitation; approximately 28 percent had difficulty with at least one activity of daily living such as eating, bathing, dressing, using the restroom independently, and walking.3

Functional decline puts older adults at risk for entering into nursing homes, yet the vast majority of older adults want to continue to age in place. Aging in place is defined as “… being able to remain in one’s current residence even when faced with increasing need for support.”4,5 Among individuals ages 65 to 74, about 97 percent reside in the community and nearly 90 percent of them desire to age in place.6 Additionally, there are many economic, social and health advantages to aging in place.7,8 Therefore, the question of how to effectively help older adults age in place is of great national importance.

Despite the importance of this question, most of the research has focused on what factors place older adults at risk of moving from community living to a nursing home rather than what can be done to prevent this transition. Known risk factors for long-term care placement in nursing homes include older age, type and number of chronic physical or mental health conditions, recent hospitalizations and/or emergency department visits, need for assistance with instrumental activities of daily living, social isolation, minority race or ethnicity and economic disadvantage.9,10

Peer to peer (P2P) support may be one community service that promotes aging in place in older adults. P2P support programs can be operationalized in a variety of different ways depending on the community. Generally, these programs involve matching one older adult with a less-able older adult in the same community. Peer supporters can visit their client in their homes, take them to the grocery store or doctor’s appointments, and are a connection point with whom the older adult can engage with socially. The P2P programs often include training for the peer supporters with topics such as developing a P2P relationship, the importance of companionship, basic health and emotional health needs of at-risk older adults; providing emotional support and troubleshooting of particular issues that might arise in a relationship.

Several studies have previously investigated the impact of P2P support on older adults’ general health and well-being. 11–15 One program evaluation found older adults who were experiencing loneliness and who began receiving a weekly visitor had improved life satisfaction and improvements in worth and social integration.11 These findings have been replicated in studies that found improvements in physical health, general health, social function and satisfaction among socially isolated older adults.13–15 Likewise decreases in anxiety and depressive symptoms12,15,16 and increased socialization12,15 have been reported in older adults who receive P2P support. One qualitative study in Australia suggested that volunteer programs that addressed recipients’ social, emotional, and mobility needs can contributed to older adults remaining in their homes.14

While there is substantial literature suggesting P2P support programs improve general health and wellbeing few studies explored which components of P2P support older adults find most meaningful. We sought to explore this gap in the literature qualitatively from the perspective of older adults who receive these services. The purpose of this study was to understand the challenges that older adults have maintaining their independence and to identify how P2P support services can facilitate continued independence. By understanding what components of P2P support programs are most important to older adults, we can strategically target further development of these elements and continue to increase the potential impact of P2P support in helping older adults age in place.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

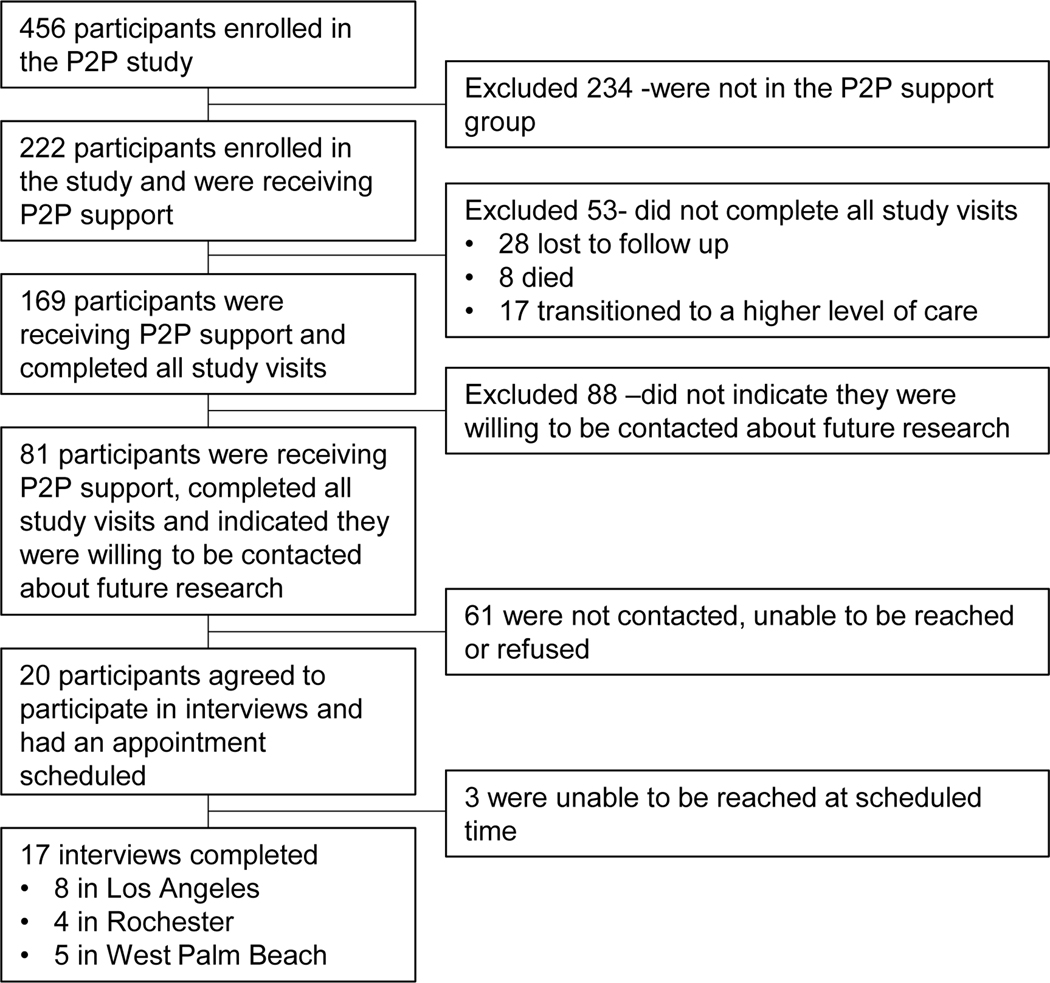

We completed 17 interviews by telephone with older adults in Los Angeles, California; Rochester, New York; and West Palm Beach, FL. These were the three cities where we conducted a quantitative comparative-effectiveness study that compared the effectiveness of P2P support to the effectiveness of standard community services in helping older adults age in their communities. All participants in this study had previously participated in the quantitative study. To be eligible for the quantitative study, participants needed to be 65 years of age or older, speak English or Spanish, be living independently in their own home, apartment or independent retirement community, and be receiving an average of 1 hour of help from their peer per week. Older adults also needed to be eligible for or currently receiving peer support, which means they would have one or more of the following characteristics: were living at or below poverty level or on a fixed income that did not meet their living expenses; were socially isolated; had chronic illnesses; or frequently used community services or resources that the organization offered (such as social gatherings, a meal, or bereavement services). In contrast to most studies of P2P, which focused on improving a specific disease outcomes, our study focused on improving general health. Eligibility criteria for this qualitative study included: (1) completed the quantitative study including all follow up visits, (2) received peer support, (3) had previously agreed to be contacted about future research and (4) were willing to participate in one interview by telephone. Figure 1 describes how participant selection proceeded.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram for Selection of Participants for Qualitative Interviews

Eighty one participants from the quantitative study who met inclusion criteria were stratified by sex (male/female) and the females were further stratified by age (older age (≥80 years old)/younger age (65–79 years old)). We did not stratify the men by age due to the small number of eligible men. We were interested in exploring how sex and age influenced their experiences and therefore participants were purposefully selected based on site, sex and age (younger females, older females, and males). Research coordinators at each site recruited participants by phone in each of the three groups on the site-specific list that was randomly generated. The research coordinators called participants in each of the three subgroups starting at the top of the list and set up appointments with 20 individuals who were available and interested in being interviewed.

We proceeded with sampling, data collection and preliminary data analysis concurrently and stopped data collection after 17 interviews because participant responses became redundant, attempts to uncover new themes failed to reveal novel data and the study team deemed data saturation had been reached.17 In addition to the 17 completed interviews, two participants did not answer their telephones at the time of their appointments or on subsequent attempts to contact them and one participant was unable to call into the telephone line for the interview.

Data Collection

One research team member trained in qualitative research methods conducted all interviews over the telephone in a private room. We audio-recorded all interviews; they lasted an average of 30 minutes. We transcribed the audio files verbatim and reviewed them for accuracy. The Institutional Review Board deemed the study as a quality improvement study and all participants gave verbal consent prior to participation. All participants who completed interviews received a $25 gift card in appreciation of his or her time.

We used semi structured interviews to understand older adults’ experiences in the community.18 The semi-structured interview questions are listed in Table 1. We began with open ended questions designed to elicit participants’ broad responses. Probes were used as follow-ups to each question to elicit the participant’s response to any related topics that the participant doesn’t bring up on their own. For example, in the interviews we were interested in independence broadly, and transportation more specifically. If a participant did not bring up transportation in their discussion of independence, we followed up with a specific probing question to understand the challenges they faced with transportation.

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview questions

| 1. What it is like to live in [city name] as an older adult? |

| 2. Are there ways that the community is organized that makes it easier or harder for adults to live independently? |

| 3. What has your experience been like with having a peer supporter? |

| 4. What was the most meaningful or helpful aspect of the program? |

| 5. What has it meant for you to have a peer supporter? |

| 6. What do you think is the best way for us to talk to other older adults about peer support? |

| 7. Initially, why did you want a peer supporter, and how did you get engaged in the program? What was it like to get signed up? |

| 8. Is there anything else you’d like to tell me? |

Data Analysis

We used deductive and inductive conventional content analysis to analyze the data.19 The deductive component allowed us to include codes a priori based on the domains of the interview questions; the inductive component of analysis allowed us to include emerging domains. To begin the analysis, we developed a preliminary codebook based on the semi-structured interview guide. One study team member, used the preliminary codebook to code several interviews.

Next, the whole study team met to review codes, add new codes, refine code definitions, and finalize the codebook. For the remaining interviews, one study team member coded the interviews and a second study team member reviewed the coding. As coding proceeded, we did not add codes but instead refined code definitions to reach agreement among study team members. A copy of the sections of the codebook used in this analysis are included in supplementary table 1.

Once coding was completed, we grouped codes into higher-level categories that had meaning to participants. We then explored how these higher-level categories were similar or different among participants from different cities of different sexes and of different ages. Although we looked for differences by sex and age we did not find that experiences differed in different sex or age groups. Therefore, we report the findings globally and as applicable describe how the findings differed by site. We used qualitative software, Dedoose20 developed by SocioCultural Research Consultants LLC (Los Angeles California), as a tool to code our data.

RESULTS

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the 17 interview participants. Overall, participants identified many factors that made it challenging to maintain their independence as they aged including declining abilities, difficulties with mobility including transportation, and increasing cost of living. In Los Angeles specifically, housing costs were highlighted as a major barrier to independence. Although participants described many challenges with maintaining their independence, they often simultaneously described how having a peer supporter facilitated their independence and provided them with a new friend.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Pseudonym | Gender (Male/Female) | Age Group | Years of Schooling | Site(LA, Rochester, WPB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | Male | N/A | 13 | LA |

| Participant B | Female | Older | 12 | LA |

| Participant C | Female | Older | 15 | LA |

| Participant D | Male | N/A | 20 | LA |

| Participant E | Male | N/A | 6 | LA |

| Participant F | Female | Older | 10 | LA |

| Participant G | Female | Younger | 14 | LA |

| Participant H | Female | Younger | 13 | LA |

| Participant I | Female | Younger | 14 | Rochester |

| Participant J | Female | Younger | 18 | Rochester |

| Participant K | Female | Older | 16 | Rochester |

| Participant L | Male | N/A | 17 | Rochester |

| Participant M | Female | Older | 12 | WPB |

| Participant N | Female | Older | 14 | WPB |

| Participant O | Female | Younger | 12 | WPB |

| Participant P | Male | N/A | 14 | WPB |

| Participant Q | Female | Younger | 18 | WPB |

Challenges with Independence

Declining Abilities with Age

Eleven of the participants acknowledged that they could not do all the things they could do even one year ago, such as getting around their homes or going shopping. For example, one participant said, “Well, now it’s changed because I’m getting older and I could use some more help, but I’m not getting any help.” (Participant F) Similarly, another participant acknowledged that abilities change very quickly. This participant said, “I went to the hospital three times in a row and I never really felt well since those episodes and so I know that things can change very quickly.” (Participant J)

Specifically, four of the participants acknowledged that they were lucky to be as independent as they were. One woman from West Palm Beach said, “I’m one of the lucky ones who is 86 and still able to function really well, and not be—and I’m not ill.” (Participant M) Declining abilities with age was a major challenge for many of the participants.

Mobility

Fifteen of the participants described struggling to get around their neighborhoods. One woman said, “Because in the area that I live, you know, it’s very hard to get to public transportation. And it’s kind of dangerous and hard for me to walk at this point.” (Participant C) The experience of giving up one’s car was common and was often associated with losing aspects of one’s independence and relying on others to get places.

Participants described relying on others in different ways. For example, one woman said, “I was leasing the car and it just got very expensive. Plus, the insurance and the gas, so I just—and I can walk where I live, I can walk to my clubhouse. I can walk to most of my activities. And I’m lucky enough to have some friends who are bridge players who take me to the duplicate bridge game. And so, so far so good.” (Participant M) Similarly, this woman also relied on her friends for transportation. She said, “I really feel like I can manage because of my friends, some of my friends are younger, and some of them still drive.” (Participant J) Another woman had a different experience with losing her ability to drive: “Because I don’t drive, number one. So that means I’m locked in having to beg rides. And, I hate doing this.” (Participant N) Mobility and maintaining the ability to get places was a major challenge for the older adults we interviewed.

Cost of Living

Cost of living was another major challenge that these older adults face. One woman was frustrated with the increasing costs of living: “[T]he only thing I can say is that I wish I had some more money. That’s about it, but that’s no one can help me with that. My kids do a little bit but other than that, my life is fine … You know everything is so expensive today.” (Participant M) Another woman said that she gave up her car because of cost. “I gave up my car, because I just couldn’t afford it anymore.” (Participant N) Participants in Rochester had an easier time finding affordable housing options. One man said, “It’s pretty well organized. I’m a low-income senior and there are many apartment complexes, in the area that are available for people with lower income, and so they have served me well.” (Participant L)

In contrast to participants from Rochester and West Palm Beach, participants in Los Angeles regularly commented on cost of housing as a challenge in maintaining their independence. One man said, “Because today all of my income is not enough to pay the rent for one bedroom, even not for a studio. But my Social Security would not be enough to pay the rent. So there are houses, apartment for low income with lower rent is also a great thing.” (Participant D) Another woman said, “Well I love Los Angeles. I love the weather. I just really love Los Angeles, but my income makes it that I live in one room. And that’s kind of a strange situation.” (Participant G) Increasing cost of living was a major concern mentioned by eight participants in this study.

Value of Peer-to-Peer Support

Maintaining Independence

Fourteen of the participants stated that they wanted to continue living in their own home and they recognized that their peer supporter helped them maintain their independence by taking the participant to the doctor and grocery store. One woman described the value of the services she received this way, “I live in Los Angeles 39 years. And I’m getting older. I don’t drive where I live, over 30 years, I have macular degeneration. But I do have a part time [peer], they give me from Jewish Family Service… now [my peer supporter] comes for 3 hours 2 days a week so I can get out. Otherwise, it would be impossible to stay in the house, because there is no shopping nearby where even a bus goes by.” (Participant F) Similarly, a man said this about his peer supporter: “Well, I’m able to get a haircut and I’m able to go to the grocery store. And, I wouldn’t be able to do those things without their help because I, I don’t have a car and I have some anxiety problems and some depression problems. And, the lady from Catholic Family Center that helps me shop, she actually walks around with me. And that, that makes it doable for me, otherwise I’d get too nervous.” (Participant L) The peer supporters play a vital role in helping these older adults remain in their homes through their help transporting them to doctor’s appointments, the grocery store, pet grooming appointments, religious services, exercise classes and social activities.

Friendship

In addition to helping the older adults maintain their independence, the participants also described their peer supporter as a new friend. One woman described the value of her peer supporter this way: “…It’s just very good to have someone, you know, that’s helpful to you, that gives you the strength to keep going when you’re in a lot of difficult situations like I am. You know? So it’s good.” (Participant C) Another woman said that she and her peer supporter are now almost like friends. “[Sarah] is my usual driver and I feel like she’s actually kind of become a kind of friend.” (Participant J) Participants we interviewed highlighted how having a new friend was another benefit of the P2P support program.

DISCUSSION

Participants in our study described what it was like to be an older adult with some limitations in their city and what their peer supporter did to help them maintain their independence. Participants described how their declining abilities and issues with mobility are some of the challenges they face as they attempted to maintain their independence as they age. Additionally, participants described how the P2P support program helped them maintain their independence and interact with a new friend.

Normal cognitive aging has been widely characterized in the literature.21 The lifestyle cognition hypothesis suggests that an active lifestyle and engaging in certain activities may help prevent age-associated cognitive decline.22 Some studies even suggest that social engagement is related to delayed onset of Alzheimer’s disease.23,24 Additionally, it is widely acknowledged that older adults lose physical abilities as they age. The question then becomes, how do you support older adults who want to stay in their homes as their physical and cognitive abilities decline?

P2P support programs have been shown to help older adults to maintain their independence despite decreasing cognitive and physical ability.25 Our qualitative findings support the idea that older adults find value in the P2P support programs. The older adults discussed increased ability to get out and interact in the community as a result of their peer companion. These findings are consistent with previous work which found that access to services and social support, services that many P2P programs provide, were two of the strategies that contributed to successful aging in place.26 Nonetheless, the challenges our participants faced are likely to be substantial, and peer support, alone, may not be able to completely address these challenges.

The older adults also described how P2P support was valuable because it offered them a new friend. Social isolation and loneliness are common issues among older adults that have both been associated with increases in morbidity and mortality.27,28 The issue of loneliness has become so important that the World Health Organization has included encouraging social engagement for older adults as a key strategy for age-friendly cities.29 It seems as if P2P support programs are one strategy that may contribute to increased social engagement for older adults.

Participants in our study identified issues with mobility as one of the primary challenges to independence. This is consistent with previous literature that has also found that independent of age, mobility is a critical element of one’s quality of life and independence.30 Personal health and well-being has been found to be significantly related to transportation deficiency with people in good and excellent health less likely to have transportation deficiencies. 31 It is clear from our study that people meet these mobility challenges in varied ways –living in areas where they can mostly walk to activities, relying on friends or utilizing P2P support. There is clearly a continued need for communities to work to improve access to transportation for older adults in an aging society. In addition, our data support the need for transportation options to be low or no cost, given the financial challenges experienced by older adults.

Our work underlines the importance of financial challenges in the lives of older adults. The relationship between financial hardship and disability is complex. Older adults with high needs for long-term services and supports are more likely to report financial hardship related to paying for food, rent, utilities, medical care, and prescription drugs.32 At the same time perceptions of financial hardship associate with symptoms of depression, 33 in particular for those with chronic conditions.34 Independent of other sociodemographic factors, self-reported financial hardship is strongly associated with poor self-rated health. Our study highlights how worries about income adequacy can serve as stressors for older adults who wish to age in place with community supports.

This study has several limitations. While the results raise important questions for further investigation related to challenges faced by older adults wishing to age in place in cities, they may not be generalizable to older adults in other urban settings across the United States. Additionally, our recruitment strategy was an opt-in system, and it is possible that the participants that had positive experiences with P2P support were more likely to participate in the study. Finally, while the older adults in the quantitative study were racially and ethnically diverse, the participants in this study all self-identified as non-Hispanic white. Thus, we may have only captured the experiences of white older adults.

The results of this study provide us with a better understanding of the challenges that older adults with declining abilities face as they strive to maintain their independence. These results also clarify what services older adults find most useful within P2P support programs. Clearly, supporting mobility by providing rides to the grocery store, doctor’s appointments and social activities should continue to be a priority for P2P. Additionally, P2P support programs should consider the importance of the peer relationship in reducing loneliness and isolation. Overall, the qualitative findings indicate that the older adults who receive peer support services perceive the services to be highly valuable in helping them surmount the challenges of aging in place. Communities should continue to invest in P2P as a way to support older adults to age in place.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to all of the participants who agreed to be interviewed for this study as well as the support of the entire study team and our four partner organizations: The Alliance for Strong Families and Communities, Alpert Jewish Family Service of West Palm Beach, Community Place, and Jewish Family Service of Los Angeles.

FUNDING

This project was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) contract number [CER-1310–07844].

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Schwei, BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine University of Wisconsin Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, 800 University Bay Drive, Suite 310; Madison, WI 53705;.

Amy W. Amesoudji, University of Wisconsin Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

Kali DeYoung, BioTel Research.

Jenny Madlof, Ferd & Gladys Alpert Jewish Family Service of West Palm Beach.

Erika Zambrano-Morales, California State University---Los Angeles.

Jane Mahoney, Department of Medicine University of Wisconsin Madison School of Medicine and Public Health.

Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Departments of Medicine and Population Health Department of Medicine Dell Medical School The University of Texas at Austin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Washington DC: Census Bureau; 2014:25–1140. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Being. https://agingstats.gov/docs/PastReports/2012/OA2012.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 3.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: Key Indicators of Well-Being. https://agingstats.gov/docs/LatestReport/Older-Americans-2016-Key-Indicators-of-WellBeing.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 4.Greenfield EA. Using Ecological Frameworks to Advance a Field of Research, Practice, and Policy on Aging-in-place Initiatives. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preface Pastalan L. In: Pastalan L, ed. Aging in Place: The Role of Housing and Social Support. New York: Haworth Press; 1990:ix–xii. [Google Scholar]

- 6.AARP: Seniors’ Desire to Age in Place Faces Serious Challenges. Senior Housing News. http://seniorhousingnews.com/2011/12/20/aarp-seniors-desire-to-age-in-place-faces-serious-challenges/. Published December 20, 2011. Accessed March 22, 2017.

- 7.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Measuring the Costs and Savings of Aging in Place | HUD USER. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall13/highlight2.html. Accessed March 17, 2020.

- 8.Joosten D. Preferences for accepting prescribed community-based, psychosocial, and in-home services by older adults. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(1):1–18. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n01_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morley JE. Aging in place. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(6):489–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Larger Quantitative Studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIntyre I, Corradetti P, Roberts J, Browne G, Watt S, Lane A. Pilot Study of a Visitor Volunteer Programme for Community Elderly People Receiving Home Health Care. Health Soc Care Community. 1999;7(3):225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman LM. The Friendly Companion Program. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2003;40(1–2):123–133. doi: 10.1300/J083v40n01_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SH. [Effects of a Volunteer-run Peer Support Program on Health and Satisfaction with Social Support of Older Adults Living Alone]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(4):525–536. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.4.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson A. Improving Life Satisfaction for the Elderly Living Independently in the Community: Care Recipients’ Perspective of Volunteers. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(2):125–139. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2011.602579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geffen LN, Kelly G, Morris JN, Howard EP. Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):279. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1310-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler SS. Evaluating the Senior Companion Program: a mixed-method approach. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;47(1–2):45–70. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowen GA. Naturalistic Inquiry and the Saturation Concept: A Research Note. Qual Res. 2008;8(1):137–152. doi: 10.1177/1468794107085301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project | Semi-structured Interviews. http://www.qualres.org/HomeSemi-3629.html. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 19.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dedoose. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2018. www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel K. Normal Cognitive Aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):737–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fratiglioni L, Paillard-Borg S, Winblad B. An Active and Socially Integrated Lifestyle in Late Life Might Protect Against Dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(6):343–353. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00767-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowe M, Andel R, Pedersen NL, Johansson B, Gatz M. Does Participation in Leisure Activities Lead to Reduced Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease? A Prospective Study of Swedish Twins. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(5):P249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scarmeas N, Levy G, Tang M-X, Manly J, Stern Y. Influence of Leisure Activity on the Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2236–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenfield EA, Scharlach A, Lehning AJ, Davitt JK. A Conceptual Framework for Examining the Promise of the NORC Program and Village Models to Promote Aging in Place. J Aging Stud. 2012;26(3):273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dupuis-Blanchard S, Gould ON, Gibbons C, Simard M, Éthier S, Villalon L. Strategies for Aging in Place. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2015;2. doi: 10.1177/2333393614565187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luanaigh CO, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1213–1221. doi: 10.1002/gps.2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. The Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/278979/WHO-FWC-ALC-18.4-eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- 30.Spinney JEL, Scott DM, Newbold KB. Transport mobility benefits and quality of life: A time-use perspective of elderly Canadians. Transp Policy. 2009;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2009.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S. Assessing mobility in an aging society: Personal and built environment factors associated with older people’s subjective transportation deficiency in the US. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 2011;14(5):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2011.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willink A, Davis K, Mulcahy J, Wolff JL, Kasper J. The Financial Hardship Faced by Older Americans Needing Long-Term Services and Supports. Issue Brief Commonw Fund. 2019;2019:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craft BJ, Johnson DR, Ortega ST. Rural-urban women’s experience of symptoms of depression related to economic hardship. J Women Aging. 1998;10(3):3–18. doi: 10.1300/J074v10n03_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Age and the effect of economic hardship on depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(2):132–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.