Abstract

The Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) is a temporary cash transfer program for workers who have reduced earnings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some workers receiving the CERB also receive provincial or territorial income assistance. A lack of clear objectives and definitions related to the CERB has led to the CERB being treated very differently by provincial and territorial income assistance (IA) programs. We look at how these different treatments of CERB under provincial income assistance programs affect IA clients across jurisdictions. We consider arguments for why the CERB should have been fully exempted from IA benefits.

Keywords: Canada Emergency Response Benefit, COVID-19, provincial income assistance benefits

Abstract

La Prestation canadienne d’urgence (PCU) est un programme temporaire de transferts monétaires destiné aux travailleurs dont les revenus ont diminué en raison de la pandémie de la COVID‑19. Certains travailleurs bénéficiant de la PCU reçoivent également de l’aide provinciale ou territoriale au revenu. Les objectifs et les définitions de la PCU n’ayant pas été clairement établis, le traitement dont elle fait l’objet varie considérablement selon les programmes d’aide au revenu provinciaux et territoriaux. Les auteures se demandent en quoi ces différences de traitement de la PCU par les programmes provinciaux d’aide au revenu touchent les clients de l’aide au revenu, selon les administrations. Elles se penchent sur les arguments qui auraient dû militer en faveur de l’entière exclusion de la PCI dans le calcul des prestations d’aide au revenu.

Mots clés : COVID‑19, Prestation canadienne d'urgence, prestations provinciales d'aide au revenu

Introduction

The web of income and social support programs across Canada is complex. Along with federal income support programs that are available nationally, each province and territory offers its own income assistance (IA) programs (sometimes referred to as “welfare” or “funders of last resort”), each with different rules and eligibility requirements. On top of this web of programs, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government made available the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), a temporary cash benefit of $2,000/month, to workers whose earnings were reduced to below $1,000/month due to the pandemic. Each province and territory has chosen to treat the CERB differently for the purposes of their IA programs. Some jurisdictions have completely exempted the CERB and will allow their IA clients to pocket the entire amount of the CERB while maintaining their provincial/territorial IA benefit levels. Other jurisdictions have chosen not to exempt the CERB, meaning that IA clients who receive the CERB will no longer receive IA benefits. Finally, some jurisdictions have taken a middle route and chosen to partially exempt the CERB, implying that IA clients may be able to keep some of the IA benefits.

In this paper, we look at how these different treatments of CERB under provincial income assistance programs affect IA clients across jurisdictions. We focus, in our examples, particularly on IA benefits of single adults, as single adults represent the vast majority of IA clients (Falvo 2015; Petit and Tedds 2020). It is important to note that single adult IA clients universally receive the lowest IA benefits of any family type. This means that our results also show the worst possible outcome related to the treatment of CERB for IA clients. First, we find that for IA clients who receive the CERB, their IA benefits plus CERB benefits exceed the market basket measure (MBM) of income poverty regardless of how the provincial or territorial IA program treats the CERB. Although this is good news, we argue that it is temporary: without the CERB, which is currently intended to be a temporary measure, all IA clients (with the exception of AISH clients in Alberta) receive IA benefits below the MBM. Second, we find that IA clients in jurisdictions that have fully exempted the CERB attain a higher level of the MBM than IA clients in jurisdictions that have partially exempted or not exempted the CERB. For jurisdictions that are partially exempting the CERB for IA clients, we find that, regardless of the partial exemption, many IA clients in these jurisdictions will not receive IA benefits: the partial exemption leaves a large portion of the CERB non-exempt, and, when this is deducted from the IA benefit amount, it drives IA benefits to zero. IA clients in the jurisdictions that have partially exempted the CERB have their IA benefits reduced to zero the same way as in jurisdictions that have not exempted the CERB. Finally, we find that some IA clients who receive the CERB may have a lower total monthly income than before COVID-19 began (e.g., when they were employed) if their loss of earnings plus their loss of IA benefits exceeds $2,000 (the amount of the CERB). This is true for clients in IA programs that are relatively more generous, such as AISH in Alberta, Disability Assistance in British Columbia, and SAID in Saskatchewan.1 This occurs due to the interaction between the program design and treatment of CERB, highlighting the importance of understanding interactions between programs.

The different treatment of the CERB across jurisdictions for IA clients, combined with the diverse program designs of IA programs across jurisdictions, means that IA clients who receive the temporary CERB are treated asymmetrically during the COVID-19 pandemic dependent on where they live. For example, IA clients living in Golden, BC who receive the CERB will receive both their entire IA benefit and the full amount of the CERB, and only those who had earned over $2,000/month prior to the pandemic will see a decline in their total monthly income while receiving the CERB. However, persons living in Canmore, AB, less than an hour away from Golden, BC, will see their IA benefits decrease if they receive the CERB, potentially going down to zero in the months when they are collecting the CERB. Further, persons receiving Alberta’s Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) and who were earning at least $725/month will have a lower monthly total income while collecting CERB than before COVID-19.

This difference in how various IA programs are treating the CERB stems from a lack of clear objectives and definition of the CERB. The CERB could be seen as akin to EI, which provides employment insurance to workers and is paid out of deferred earnings. In this case, an IA program would deduct CERB one for one from IA benefits. Or CERB could be viewed as a direct replacement for earned income and thus be treated by IA programs in the same manner in which earned income is treated—with a partial exemption. Finally, the CERB could be viewed akin to a tax benefit program such as the Canada Child Benefit or the Canada Workers Benefit. In this case, the CERB would be fully exempted and not impact IA benefits. While the CERB was rushed through in order to be responsive to economic conditions, it is important to note that the federal Employment Minister Carla Qualtrough asked the provinces not to claw back the CERB (Stapleton 2020). Given that there was clear thought at the federal level about the treatment of the temporary CERB by provincial IA programs, the federal government still opted not to clarify the objectives of CERB to ensure the outcome that they appear to have preferred. As a result, this paper provides clear lessons to be learned related to the design and administration of future emergency benefit programs such as the CERB.

There are good arguments as to why jurisdictions should fully exempt the CERB, particularly because the CERB is a temporary benefit in response to severe economic circumstances. First, the cost of living has increased for low-income households during COVID-19 due to the closing of public services such as food banks, public libraries, and other NGOs that provide vital services. Fully exempting the CERB provides IA clients with additional income to help cover these costs, given that before COVID-19, their IA benefits were lower than the MBM, leaving them with little money saved after spending on day-to-day necessities. Second, fully exempting the CERB reduces income volatility and would provide IA clients with the temporary opportunity to save and create a stable financial foundation, potentially reducing IA caseloads and recidivism rates. Finally, jurisdictions that are not fully exempting the CERB are penalizing work for IA clients who have met the expectations of their IA programs and have put in the effort to find work. IA programs tend to have complex and punitive clawback rates on employment income. By further reducing IA benefits for those who receive the CERB, this adds another disincentive to finding work in the first place. IA programs should consider these incentives carefully.

CERB Program Details

The CERB is one part of a bigger COVID-19 economic response plan: it is a temporary income support program for workers who have significantly reduced employment earnings due to COVID-19. It was announced on 18 March 2020 by the Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, and legislation was passed on 23 March 2020. Details regarding what the CERB would look like were released with an amendment on 15 April 2020 that shored up some gaps that had been identified. Applications for the CERB were accepted beginning 6 April 2020 for the previous month. The following details the CERB as of 10 June 2020 (the time of writing this).2

To be eligible for the CERB, a person must meet the following conditions:

- He, she, or they must be a worker:

- at least 15 years of age; and

- a resident of Canada; and

- for 2019 or in the 12 month period preceding application for the CERB, have had a total income of at least $5,000 from employment, self-employment, EI benefits, or other payments related to pregnancy, newborn children, or adoption.

- Workers are eligible for the CERB if

- they cease working for reasons related to COVID-19 for at least 14 consecutive days within the four-week period for which they are applying for the benefit; and

- they have not ceased work voluntarily; and

- they do not receive more than $1,000 of employment or self-employment income within those same four weeks; and

- they do not receive any EI benefits or other benefits related to pregnancy, newborn children, or adoption.

Those who apply for the CERB receive $2,000 for each four-week period, regardless of their total annual income. The benefit is a flat amount, meaning that regardless of any person’s individual or family circumstances, so long as he, she, or they meet the CERB conditions, he, she, or they receive $2,000 each four-week period. The maximum number of weeks the CERB can be claimed for is 16 weeks. An eligible person must reapply every four weeks to receive the monthly installment of CERB. Under these rules, a person could receive up to $8,000 in CERB benefits by applying every four weeks. The CERB is a taxable benefit; however, the tax on the CERB is not deducted at the source (unlike EI), meaning that taxes on the CERB will be assessed upon completion of a 2020 tax return.

To deliver payments to Canadians in a fast and simple manner, the CERB is being jointly delivered by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and Service Canada (through the EI program). The application is online and is short and simple: no supporting documents to prove eligibility are required. At the time of application, eligibility is not being adjudicated. This allows the CRA/Service Canada to process the application and provide a payment within 10 days of the application. When eligibility is assessed, those who were not eligible but received a payment will have to pay back what they erroneously received; however, under the current rules, there will be no penalty (e.g., interest charged).3

Treatment of CERB by Provincial IA Programs

To understand how the CERB is being treated by IA programs, it is first informative to understand how income is treated for the purpose of IA programs and how IA benefits are calculated. In all jurisdictions, to determine the IA benefit level (B), first, the maximum benefit (Max(B)) is determined, based on factors such as family type, family size, and ability to work. Next, non-exempted income (NE) is deducted from that maximum benefit amount. Equation 1 shows this as a simple equation:

| (1) |

NE is found by taking income from any source (Y) and deducting from Y all exempted income (E). In other words,

| (2) |

Y can be further disaggregated into (a) gross earned income (Ye) and (b) gross income from other sources (Yo). Yo can include anything from dividend and interest/investment income to court settlements to spousal and child supports to tax refunds/other benefits to rental income and so on. In other words,

| (3) |

E includes both deductions and exemptions. Earnings deductions (De) are subtracted from Ye and include mandatory earnings deductions deducted at source such as Canada Pension Plan (CPP) contributions and employment insurance (EI) contributions. What is included in De differs by jurisdiction. Other deductions (Do) are subtracted from Yo and can include income tax deducted at source from employment insurance benefits and essential operating costs of renting self-contained units. What is included in Do also differs by jurisdiction.

Finally, also included in E are exempted earnings (Ee) and other exemptions (Eo). Ee is subtracted from Ye. Ee is calculated by first determining the earnings exemptions threshold (which differs by province).4 Any earnings below that threshold are exempted and any earnings above that threshold may be exempted, depending on the “phase-out” rate. For example, in Alberta, Alberta Works clients who are single and are expected to work have an earnings exemption threshold of $230/month plus 25 percent of earnings over $230/month; the phase-out rate is 75 percent. A client making $300/month (Ye) would have Ee = $230 + ($300–$230) × 0.25 = $247.50.

Last, Eo is subtracted from Yo. Eo is generally comprised of a lot of different sources of income. What precisely is included in Eo differs by jurisdiction, but it can include things such as tax refunds, the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), and child support payments.

Expanding Equation (2), we see that NE income is calculated as

| (4) |

We now turn to how this matters for the CERB. Different jurisdictions have included the CERB in different parts of Equation (4). Ultimately, what type of income the CERB is determined by the various jurisdictions, and whether or not it is exempt impacts the IA benefit amount in Equation (1). For example, the CERB could be included in both Yo and Eo, making the CERB fully exempt; that is, Yo = Eo = CERB and NE = 0, so that the CERB has no impact on B. On the other hand, the CERB could be included in Yo but not Eo and thus not be exempt; that is, Yo = CERB and Eo = 0, so that NE = CERB. Finally, the CERB could be included in Ye and have Ee apply, so that the CERB is partially exempt; that is, Ye = CERB and Ee > 0, so that 0 < NE < CERB and the CERB has some impact on B.

Table 1 provides details on how each IA program is treating the CERB. British Columbia, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories have all fully exempted the CERB; they are setting Yo = Eo = CERB, so that NE = 0, and the CERB has no impact on B. On the other hand, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island have decided to treat the CERB as other income (Yo = $2,000) that is completely non-exempt (Eo = 0), so that NE = $2,000: for these provinces, the CERB is not exempt.

Table 1:

Treatment of CERB across Provincial IA Programs

| Jurisdiction | Program | Classification of CERB | Treatment of CERB (Single Adults)a | How Much of CERB Is Exempt (E) (Single Adults) | How Much of CERB Is Non-Exempt (NE) (Single Adults) | Access to IA Benefits (Such as Health-Related Benefits)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Temporary Assistance (TA) | Exempt income Eo | Exempt (no clawback) | $2,000/month | $0 | No change. CERB recipients have access to all TA-related supports. |

| Disability Assistance (DA) | Exempt income Eo | Exempt (no clawback) | $2,000/month | $0 | No change. CERB recipients have access to all DA-related supports. | |

| Alberta | Alberta Works (AW) | Earned income Ye – Ee | $230 exempt, remaining 25% exempt (75% clawback rate) | $672.50/month | $1,327.50/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive AW income benefits will retain their health benefits. |

| Assured Income to the Severely Handicapped (AISH) | Passive business income Yo – Eo | $300 exempt, remaining 25% exempt (75% clawback rate) | $725/month | $1,275/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive AISH income benefits will retain their health benefits. | |

| Saskatchewan | Income Support (SIS) | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for one from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | Unknown whether CERB recipients who no longer receive SIS income benefit will retain access to other SIS-related benefits. |

| Assured Income for Disability (SAID) | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for one from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | Unknown whether CERB recipients who no longer receive SAID income benefits will retain access to other SAID-related benefits. | |

| Manitoba | Employment and IA (EIA) | Earned income Ye – Ee | $200 is exempt, remaining 30% is exempt (70% clawback rate). | $740/month exempt | $1,260/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive EIA income benefits will continue to receive drug, dental, and optical benefits. |

| Ontario | Ontario Works (OW) | Earned income Ye – Ee | Amount less than earnings exemption is exempt; amounts above earnings exemption clawed back at 50% | $1,100/month | $900/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive OW income benefits will continue to be OW clients and will retain their health benefits. |

| Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) | Earned income Ye – Ee | Amount less than earnings exemption is exempt; amounts above earnings exemption clawed back at 50% | $1,100/month | $900/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive ODSP income benefits will continue to be ODSP clients and will retain their health benefits. | |

| Quebec | L’aide Sociale et Social Solidarity | Earned income Ye – Ee | $200 is exempt; remainder will be clawed back at 100% | $200/month | $1,800/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive SS income benefits will continue to receive health-related benefits. |

| Nova Scotia | IA | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for one from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive IA income benefits will continue to receive drug coverage and the bus pass. |

| New Brunswick | Social assistance | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for one from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive SA income benefits will keep health benefits. |

| Newfoundland | Income Support | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for one from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive IA benefits will retain drug coverage. |

| PEI | Social Assistance | Non-exempt other income Yo | Deducted one for ne from benefits | $0 | $2,000/month | CERB recipients who no longer receive IA benefits will continue to receive medical, optical, and dental benefits. |

| Yukon | Social Assistance | Exempt income Eo | Exempt (no clawback) | $2,000/month | $0 | No change |

| Northwest Territories | IA | Exempt income Eo | Exempt (no clawback) | $2,000/month | $0 | No change |

Information for these columns was collected from Tweddle and Stapleton (2020).

Finally, some jurisdictions have partially exempted the CERB. Alberta has elected to treat CERB income as “passive business income” (Yo = $2,000) for AISH clients and will partially exempt $725/month (Eo = $725) of the $2,000 monthly CERB payment, leaving $1,275 from the CERB as non-exempt income (NE = $1,275). Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, and Alberta Works in Alberta have elected to treat CERB income as earned income (Ye = $2,000) subject to the earnings exemption (Ee > 0). For example, IA clients in Manitoba will have $740 of the CERB payment exempt (Ee = $740). This leaves $1,260 of the $2,000 CERB payment as non-exempt (NE = $1,260).

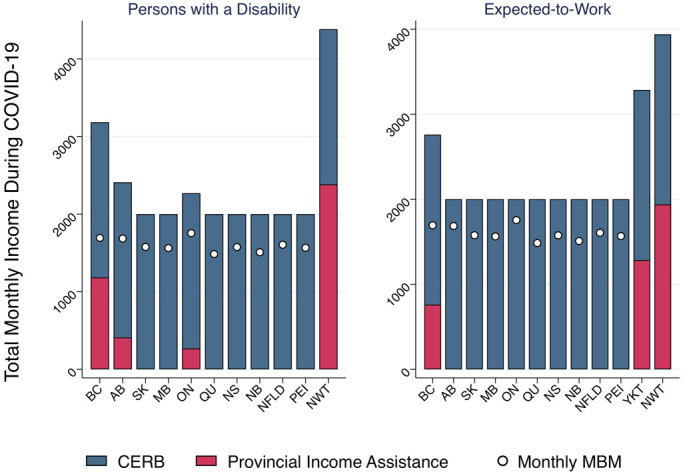

The classification of the CERB has an impact on IA benefits. Table 2 provides details on the maximum IA benefit a single adult IA client may receive (e.g., one who has no other income) and the maximum IA benefit a single adult IA client receiving the CERB (and no other income) may receive by jurisdiction and program. Also included in Table 2 is a comparison of the maximum monthly benefits of single adult IA clients relative to the market basket measure (MBM) threshold of income poverty in months in which single adult IA clients receive the CERB and in months when they receive only the usual (maximum) IA benefit and no CERB. If the ratio of benefits to MBM is equal to one, the benefits are exactly equal to the MBM. If the ratio is greater than one, this indicates that the benefits are greater than the MBM. If the ratio is less than one, this indicates that the benefits are less than the MBM. Since the MBM is regional (as opposed to provincial), in each province, we use the MBM threshold for the largest city by population.5 The 2018 MBM threshold is used. Figure 1 provides a visual of the monthly IA benefits plus CERB a single adult IA client may receive during months they receive the CERB relative to the monthly MBM.

Table 2:

Maximum IA Benefits by Province and Program when Clients Collect the CERB

| Jurisdiction | Program | Treatment of CERB | Maximum Monthly IA Benefit (Single Adults) | Ratio of Maximum Monthly Benefit to MBMa | Non-Exempt Amount of CERB | Maximum Monthly IA in Month when Receiving CERB | CERB + IA in Month Receiving CERB | Ratio of Monthly CERB + IA to MBMa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Temporary Assistance | Fully exempt | $760 | 0.45 | $0 | $760 | $2,760 | 1.63 |

| Disability Assistance | Fully exempt | $1,183.42 | 0.70 | $0 | $1,183.42 | $3,183.42 | 1.88 | |

| Alberta | Alberta Works (AW) | Partially exempt | $745 | 0.44 | $1,327.50 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.19 |

| Assured Income to the Severely Handicapped (AISH) | Partially exempt | $1,685 | 1.00 | $1,275 | $410 | $2,410 | 1.43 | |

| Saskatchewan | Income Support (SIS) | Not exempt | $860 | 0.55 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.27 |

| Assured Income for Disability (SAID) | Not exempt | $1,064 | 0.67 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.27 | |

| Manitoba | EIA | Partially exempt | $771 | 0.49 | $1,260 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.28 |

| EIA (disabilities) | Partially exempt | $1,039.50 | 0.67 | $1,260 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.28 | |

| Ontario | Ontario Works (OW) | Partially exempt | $733 | 0.42 | $900 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.14 |

| Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) | Partially exempt | $1,169 | 0.67 | $900 | $269 | $2,269 | 1.29 | |

| Quebec | Social Assistance | Partially exempt | $710 | 0.48 | $1,800 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.35 |

| Sociale Solidarite | Partially exempt | $1,088 | 0.73 | $1,800 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.35 | |

| Nova Scotia | IA | Not exempt | $586 | 0.37 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.27 |

| Disability Support Program | Not exempt | $850 | 0.54 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.27 | |

| New Brunswick | Transitional Assistance | Not exempt | $564 | 0.37 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.33 |

| Enhanced Assistance | Not exempt | $797 | 0.53 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.33 | |

| Newfoundland | Income Support | Not exempt | $906 | 0.56 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.25 |

| Income Support (PWD) | Not exempt | $906 | 0.56 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.25 | |

| Prince Edward Island | Social Assistance | Not exempt | $988 | 0.63 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.28 |

| AccessAbility Supports | Not exempt | $1,163 | 0.75 | $2,000 | $0 | $2,000 | 1.28 | |

| Yukon | Social Assistance | Fully exempt | $1,342 (Nov.–Mar.), $1,285 (Apr.–May, Oct.), $1,227 (June-Sept.) | — | $0 | $1,285 (Apr.–May, Oct.), $1,227 (June-Sept.) | $3,285 (Apr.–May, Oct.), $3,227 (June-Sept.) | — |

| Northwest Territories | IA | Fully exempt | $1,939 | — | $0 | $1,939 | $3,939 | — |

| IA (PWD) | Fully exempt | $2,383 | — | $0 | $2,383 | $4,383 | — |

Notes: All numbers presented here are for single adults who own/rent their place of residence. The first program presented for each province is transitional/temporary assistance for those expected to work. The second program presented for each province is for persons with disabilities. Since the MBM is regional, we use the MBM for the largest city by population in each province. The 2018 MBM is used. The MBM is not available for the Territories.

Information on the MBM thresholds was collected from Statistics Canada (2020c).

Figure 1:

Total Monthly Income during COVID-19 by Source for Income Assistance Clients, Single Adults

Source: Author’s calculations and Statistics Canada (2020c).

From Table 2 and Figure 1, we see that since British Columbia, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories have fully exempted the CERB, IA clients in these jurisdictions receive the full amount of their IA benefits in the months when they receive the CERB, along with the CERB. BC IA clients who receive the CERB receive over 1.5 times the MBM threshold.

From Table 2 and Figure 1, we also see that IA clients in jurisdictions that have not exempted the CERB will see their IA benefits drop to zero. This includes clients in Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. This is because the CERB, which is $2,000/month and non-exempt, exceeds the maximum IA benefit in all of these provinces. Recalling Equation (1), this implies that the IA benefit would be negative; thus these clients are no longer eligible for IA. Further, in these provinces, the ratio of the CERB plus IA to the MBM is, on the average, 1.28. This is lower than the MBM ratio in British Columbia.

Also from Table 2, we see that single adult IA clients in jurisdictions that have partially exempted the CERB have an outcome similar to that for clients in provinces that have not exempted the CERB. For IA clients in Alberta (Alberta Works), Manitoba, Ontario (Ontario Works), and Quebec, although these provincial IA programs have partially exempted the CERB by treating it as earned income minus exempted earnings, IA clients in these programs will receive no IA benefits in the months where they collect the CERB. This is because the exemption is not large enough: the non-exempt CERB exceeds the maximum IA benefits, so that Equation (1) results in a negative benefit amount, causing persons collecting the CERB to receive no IA benefits. In these provinces, the ratio of the CERB plus IA to the MBM is, on the average, 1.29—very similar to the ratio in the jurisdictions that have not exempted the CERB and again lower than the ratio in British Columbia.

Last, in Table 2, the fifth column reports the ratio of the maximum IA benefits to the MBM of income poverty. In every jurisdiction and program, with the exception of AISH in Alberta, this ratio is less than one. This indicates that nearly every IA program provides benefits that are less than the MBM measure of poverty. Although the ratio of the CERB plus IA benefits to the MBM seems large (e.g., larger than one), the CERB is temporary: this will not last. When it ends, IA clients will return to receiving IA benefits below the MBM. Further, prior to COVID-19, IA clients were receiving IA benefits less than the MBM, which may have impacted how much savings they had during COVID-19 to help cover rising costs of living. This is a point we will return to in the discussion.

Table 2 and Figure 1 do not tell the whole story: they only show us what the final IA benefit plus the CERB benefit will be for single adults. They do not tell us whether that amount is greater or less than the monthly income of a single adult IA client before COVID-19. In a few cases, some IA clients will have a lower monthly income when they have no employment and are collecting CERB than when they had employment and were not collecting CERB. This is true of provincial/territorial IA programs with high levels of benefits and high levels of exempt earnings.

As a thought experiment, consider a single adult IA client who is working in March 2020. In April 2020, he, she, or they lose the job for reasons related to COVID-19 and apply for the CERB. Comparing March to April, he, she, or they lose earned income and gains CERB income. Dependent on the jurisdiction in which he, she, or they reside, he, she, or they may or may not lose IA benefits. If the loss of earnings plus loss of IA is greater than the gain from the CERB, monthly income in April may be lower than in March.

There are three programs in which an IA client may have a lower monthly income when collecting CERB than when employed. First, under BC Disability Assistance (DA), although CERB is fully exempted, the earnings exemption and benefit level are sufficiently high so that DA clients earning over $2,000 may receive DA, although this is dependent on accumulated earnings. DA clients who were earning over $2,000/month and then were fired/laid off when COVID-19 hit so that they collected the CERB may have a lower total monthly income than before COVID-19. This is generally true for all recipients of CERB.

More problematically, for AISH clients in Alberta and SAID clients in Saskatchewan, total monthly income may be lower when collecting the CERB after only minimal earnings loss. For AISH clients who were earning over $725/month, the loss of earnings plus the loss of AISH benefits is greater than the CERB payment, making the change in total income negative. Likewise, for clients of SAID in Saskatchewan, the loss of earnings plus the loss of SAID may be larger than the gain in CERB benefits, dependent on a SAID’s client’s past level of earnings (as the earnings exemption is annual). For example, a SAID client with accumulated earnings below the $6,000 annual earnings exemption threshold who made $936/month or more, if he, she, or they lose employment and receive the CERB, total monthly income will be lower with the CERB than with employment.

This lower total monthly income in BC DA, Alberta AISH, and Saskatchewan SAID is partially a result of program design and should actually be commended. All of these programs have higher levels of benefits and/or more generous earning exemption thresholds than other jurisdictions. Clients of these programs are not cut off of IA benefits as quickly when they gain employment, a point we will come back to.

However, because of these more generous program designs, the loss of earnings plus the loss of IA benefits can result in a net loss of monthly income even with the gain of the CERB benefit compared to less generous program designs where, although there may be a loss of earnings and a loss of IA benefits, there is a net gain in monthly income because of the CERB. The more generous a program is, the more there is to lose and the less that the CERB can make up for that loss.

How Many People Does This Affect?

The next question to look at is how many provincial IA clients may actually be eligible for the CERB, and how many IA clients may be no longer eligible for IA benefits. To answer this question, we use data from the Social Policy Simulation Database (SPSD) from Statistics Canada. In May 2020, a COVID-19 version of the SPSD was released that allowed users to investigate federal income support benefits announced in Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan and its effects on Canadians.

The SPSD is a non-confidential, statistically representative database of Canadian individuals. It includes sufficient information on each individual to estimate his or her taxes paid and cash transfers received from the government (Statistics Canada n.d.). The underlying data upon which the representative data are largely based is the Consumer Income Survey conducted by Statistics Canada. These data are not available for the territories, nor does the SPSD provide an adequate indicator of disability status.

Table 3 provides summary statistics on the number of individuals (ages 15–64) in each province who receive provincial IA and the number of income recipients (ages 15–64) who potentially qualify for the CERB. From Table 3, we see that 4.77 percent of the Canadian population receive provincial IA, and, of those, nearly 20 percent are potentially eligible for the CERB (e.g., they were working and met the income requirements for CERB). This varies across provinces. British Columbia has the highest proportion of IA recipients potentially eligible for the CERB, at 28.44 percent, and Newfoundland has the lowest proportion of IA recipients eligible for CERB, at 4.42 percent. It is interesting to note that the provinces with the largest proportion of IA clients potentially eligible for CERB are the same provinces we identified above as having more generous program designs: British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan.

Table 3:

Number of IA Recipients and IA Recipients Who Potentially Qualify for the CERB

| Province | Number of Individuals (Population) | No. of Individuals Receiving Provincial IA | Individuals Receiving Provincial IA (%) | No. of IA Recipients Potentially Eligible for CERB | Recipients Potentially Eligible for CERB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 37,874,174 | 1,805,732 | 4.77 | 354,270 | 19.63 |

| BC | 5,168,631 | 218,789 | 4.23 | 62,234 | 28.44 |

| AB | 4,529,039 | 212,480 | 4.69 | 46,911 | 22.08 |

| SK | 1,145,273 | 55,014 | 4.80 | 11,151 | 20.27 |

| MB | 1,312,208 | 60,136 | 4.58 | 9,102 | 15.14 |

| ON | 14,727,182 | 835,823 | 5.68 | 164,882 | 19.73 |

| QB | 8,615,742 | 331,958 | 3.85 | 50,272 | 15.14 |

| NB | 750,822 | 29,481 | 3.93 | 2,866 | 9.72 |

| NS | 948,881 | 37,055 | 3.91 | 5,452 | 14.71 |

| PEI | 159,822 | 4,200 | 2.63 | 481 | 11.45 |

| NFLD | 516,574 | 20,796 | 4.03 | 919 | 4.42 |

Source: SPSD/M and author’s calculations.

From Table 3, about 5.9 percent of all IA clients who are potentially eligible for the CERB live in provinces that have not exempted the CERB. That is, 5.9 percent of all IA clients may not receive IA in the months when the CERB is available. Further, 76.5 percent of all IA clients who are potentially eligible for the CERB live in provinces that have partially exempted the CERB. As we saw in Table 2, there is the potential that these IA clients will no longer receive IA. Only 17.6 percent of all IA clients who are potentially eligible for the CERB live in provinces that have fully exempted the CERB, and thus only these clients are guaranteed to continue receiving IA benefits while receiving the CERB.

Unfortunately, the SPSDM does not adequately model provincial IA benefits, nor does it provide sufficient information to estimate provincial IA amounts. Further, the COVID-19 SPSDM model does not model how provincial IA benefits are affected by receipt of the CERB. Due to these limitations, we are unable to estimate the actual magnitude of the effect of the CERB on provincial IA recipients. To do so would require access to IA administrative data linked to tax filer data, at a minimum; however, such data are only available in the Statistics Canada Research Data Centers (RDC), which are currently closed due to the pandemic, and are only available currently for the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. When the RDCs reopen and the data are available, we plan to revisit this analysis to measure the impact these differing provincial treatments of the CERB had on IA clients.

Discussion

Prior to COVID-19, it was well documented that provincial IA programs were inadequate: in all provinces and across all programs, IA benefits leave low-income households below the income poverty line (Tweddle and Aldridge 2019). We also show this above in Table 2: the ratio of the maximum IA benefit for single adults to the MBM poverty measure is less than one in all programs except for AISH in Alberta. IA clients who work are trying to better their financial situation, and often have to overcome barriers (e.g., disabilities including mobility and access issues, addictions, metal health issues, employer bias). Usher in COVID-19 and these same IA clients are now thrown an additional curve ball: COVID-19 has resulted in the loss of jobs for many low-income workers. In March and April, persons making less than $24.04/hour had a 38.1 percent job loss compared with a decline of 12.7 percent for all other employees (Statistics Canada 2020a).

For IA clients who have lost their employment, not only do their barriers remain, but they have increased, and their costs of living have also increased. Prior to COVID-19, many low-income households used basic services to live day to day. Food banks and school lunch programs provided food to those with food insecurity, public libraries provided computers and internet access to those with limited access to technology, and social service offices, legal clinics, and NGOs provided aid with filling out application forms for various benefits and other necessary paperwork. COVID-19 has cut off or reduced access to all of these services, forcing low-income households either to go without or to purchase these items (Loopstra, Dachner, and Tarasuk 2015; McIntyre, Dutton, et al. 2016; McIntyre, Patterson, et al. 2016). Further, prices on day-to-day grocery items have increased (Statistics Canada 2020b).

There are good arguments as to why the CERB should be fully exempted by all jurisdictions, particularly because it is intended to be a temporary program. First, fully exempting the CERB for IA clients will help them cover the increasing costs of living due to COVID-19. Given that for all IA clients, the ratio of MBM to the monthly maximum IA benefit without CERB is less than one, it is highly likely that IA clients do not have accumulated savings sufficient to cover unexpected expenses. In general, Rothwell and Robson (2018) estimate that 54 percent of Canadians do not have enough savings to maintain their households at 50 percent of the median income for three months, and this increases to 70 percent to those with less than high school education. Allowing IA clients to retain their IA benefits plus the CERB would help them fill in for their likely lack of savings. Further, making up for the lack of saving to cover the increasing costs of living is particularly important during a pandemic because, if IA clients cannot cover costs such as rent, they may be forced to move.6 Moving during a pandemic increases risk of transmission of the virus, particularly if those moving cannot afford safety measures.

Second, fully exempting the CERB would allow IA clients to have a consistent and predictable stream of income during the period when the CERB is delivered: there would be no interruption in the stream of IA benefits, thus reducing (negative) income volatility. Income volatility in low-income households has been shown to lead to adverse consequences such as increased food insecurity (Bania and Leete 2007), worse emotional health (Gennetian and Shafir 2015), adverse schooling outcomes for children (Gennetian et al. 2015; Yeung, Linver, and Brooks-Gunn 2002), increased material hardship and difficulty paying bills, including rent (Schneider and Harknett 2017), and increased financial vulnerability/lower ability to cope with an unexpected expense (Schneider and Harknett 2017). Further, even if IA clients do have a higher monthly income because of CERB, providing low-income households with a temporary opportunity to build a solid financial foundation (through the accumulation of financial assets) ensures that a household has more resources at its disposal to meet its needs, increasing the likelihood of well-being and security, and can lead to greater stability, greater mobility, and the promotion of welfare exit (Robson 2008).

Third, fully exempting the CERB would avoid penalizing IA clients for working. IA clients who were working prior to COVID-19 were meeting (and potentially exceeding) the expectations of their IA programs. Not only does clawing back the CERB penalize IA clients who were trying to better themselves, but also it creates additional disincentives for IA clients to work (on top of other disincentives already baked into most IA programs).

Some writers have argued that it would not be fair to allow IA clients to retain both their full IA benefits and the CERB when low-income households who are not IA clients will only receive the CERB (see for example Boessenkool 2020). However, this positions the argument as a race to the bottom instead of considering how those on the bottom can be pulled up during unprecedented economic conditions. Policy-makers in several jurisdictions have, in fact, provided additional aid to low-income households who are not IA clients yet face the same barriers and rising costs of living as IA clients. This includes the federal government, which has provided one-time top-ups to the GST/HST credit, to the CCB, and to OAS and GIS recipients.

Finally, the different treatment of the CERB across provincial/territorial IA programs is problematic. There is no explanation as to why an AISH recipient living in Canmore, AB should be treated differently than a Disability Assistance recipient living in Golden, BC, less than an hour away. But they are treated differently. At the national level, Canada recognizes that key income benefit programs should be provided consistently across Canada. For example, all Canadians face the same eligibility requirements and program parameters for the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), OAS/GIS, the Working Income Tax Benefit/Canada Workers Benefit (CWB), and employment insurance (EI). Further, all of these programs are treated in the same manner by provincial IA programs. CERB, particularly because it is temporary, should be no different.

This raises the question of why IA programs are treating the CERB differently. One explanation may be that, because of the swiftness with which the CERB was put into place, there was very little technical guidance as to what the CERB was. Is it like EI, which is an employment insurance program meant to insure workers and paid out of deferred earnings, and thus should it be non-exempt for the purposes of IA, as EI is? Or is it a replacement for employment income, and thus should it be treated as employment income for the purposes of IA? Or is it a tax benefit program, paid out of general revenue to supplement low income, like the CCB or CWB, and thus should it be fully exempt for the purposes of IA?

Some writers have argued that CERB should be treated as earned income (and partially exempted) because it temporarily replaces lost employment income (see for example Boessenkool 2020). But it may not be this simple. Although this is indeed what the Canada Emergency Response Benefit Act purports, this is not reflected in the way the CERB is designed. If CERB were to replace lost employment income, recipients would receive a benefit amount equal to the amount of their low employment income. This is not the case. The CERB differs in one way or another from all other programs in Canada. This highlights the importance of the federal government concisely defining a program and its objectives to minimize differential treatment of programs across jurisdictions.

All of the complexity discussed in this paper demonstrates how different IA programs across Canada are, and how their interactions with federal IA programs matter. It also demonstrates how important it is to clearly and consciously define IA programs, and consider their effects on all sociodemographic groups. Although there was not time to conduct this in-depth analysis with the CERB, future federal programs can learn from the CERB experience.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Government of British Columbia (spcs46008190052) that helped support this research. We would like to thank Molly Harrington, Assistant Deputy Minister, Research, Innovation, and Policy Division, Social Development and Poverty Reduction, Government of British Columbia; Robert Bruce, Executive Director, Research Branch, Research, Innovation, and Policy Division, Social Development and Poverty Reduction, Government of British Columbia; and John Stapleton, Open Policy Ontario, for their helpful comments and information as we were preparing this paper. We would also like to thank Robin Shaban, Robin Shaban Consulting for her help with the SPSD/M, and an anonymous guest editor for helpful comments.

Appendix

Table A.1:

IA Rates for Single Adults with Disabilities

| Program | Family Type | Maximum Support Allowance | Maximum Shelter Allowance | Maximum Total Benefit | Earnings Exemption | Clawback Rate (Non-Exempt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC Disability Assistancea | Single Adult | $808.42/month | $375/month | $1,183.42/month | $12,000/year (net earnings) | 100% |

| AB AISHb | Single Adult | — | — | $1,685/month | $1,072/month (net earnings) | 50% up to $2,009/month, 100% after $2,009/month |

| ON ODSPc | Single Adult | $672/month | $497/month | $1,169/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 50% |

| SK SAIDd | Single Adult (large urban area)e | — | — | $1,064/month | $6,000/year (gross earnings) | 100% |

| MB EIAf | Single Adult | $274.80/month + $48.80/month + $7.80/month + 105/month | $603/month | $1039.50/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 70% |

| QU Social Solidarityg | Single Adult | $995/month + $93/month | — | $1,088/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 100% |

| NS DSPh | Single Adult | — | — | $850/month | $350/month (net earnings) | 25% from $350–$500, 50% from $500–$750, 75% over $750 |

| NB Enhanced Assistancei | Single Adult | $697/month + $100/month | — | $797/month | $500/month (gross earnings) | 70% |

| PEj | Single Adult | $342 (food) + $83 (essentials) + $150 (community living allowance) | $588/month | $1,163/month | $500/month (net earnings) | 70% |

| NLk | Single adult | $534 | $372 | $906 | $150/month (net earnings) | 80% |

| YTl | Single adult, not in labour force (if in labour force, same rates as those expected-to-work) | Nov.–Mar.: $242 (food) + $459 (fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) + $250 Apr., May, Oct.: $242 (food) + $402(fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) + $250 June–Sept.: $242 (food) + $344 (fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) + $250 (Whitehorse) | $514 | Nov.–Mar.: $1,592 Apr., May, Oct.: $1,535 June–Sept.: $1,477 | — | — |

| NT | Single adult | $343 (food) + $405 (disabled allowance) + $79 (clothes) + $39 (incidentals) (Yellowknife) m | Actual cost of shelter + fuel + utilities. From CMHC: $1,517 n (average for 1-bedroom) | $2,383/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 85% |

Notes: Net earnings = wages/salary – allowable deductions such as CPP/EI premiums, union dues, etc.; Gross earnings = wages/salary before deductions. All of these assume the recipient rents his or her place of residence (e.g., is not living in a long-term care facility or other shared/accommodated living situation) and is boarding with a non-relative. None of these amounts include possible supplements such as disability/community/caregiver supports, home/vehicle modification, or health-related supplements.

As of April 2019. Source: BCEA Policy & Procedure Manual (British Columbia 2020).

Current to April 2020. Source: AISH Policy Manual (Alberta 2020).

Current to September 2018. Source: Social Assistance Policy Directives: Income Support (Ontario 2018b) and Deductions from Income (Ontario 2018a).

Current to May 2020. Source: the Saskatchewan Assistance Regulations (Saskatchewan 2014).

In Saskatchewan, there are four tiers of benefits. I have included the top tier with the highest benefit level for large urban areas such Saskatoon, Regina, and Lloydminster, as well as the lowest tire with the lowest level of benefits for small rural areas and social housing units.

Current to 2019. Source: Manitoba Assistance Regulation (Manitoba 2019).

Current to February 2020. Source: Individual and Family Assistance Regulation, Chapter IV (Quebec 2020).

Current to 27 November 2019. Employment Support and IA Regulations, (Nova Scotia 2019). This is just the basic amount and does not include new programs such as the Flex program, which provides up to an additional $3,800/month dependent on the client’s needs and circumstances. Receipt of Flex funding is also dependent on available funding (there is a waiting list).

Current to May 2020. Source: General Regulation, NB Reg 95-61 (New Brunswick 2020), and New Brunswick policy manual, s. 3.9 (New Brunswick n.d.).

Current to January 2020. Source: e-mail inquiry to Hannah Bell, MLA and Social Assistance Act Regulations (Prince Edward Island 2018).

Source: Social assistance Web site (Newfoundland and Labrador n.d.) and Income and Employment Support Policy and Procedure Manual, Chapter 3: Assessment of Income (Newfoundland and Labrador 2018).

Source: Social Assistance Regulation, O.I.C. 2012/83 (Yukon 2012).

Source: Income Assistance Regulations R.R.N.W.T. 1990, c. S-16 (Northwest Territories 2019).

Source: CMHC Rental Market Report (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2020).

Table A.2:

IA Rates for Single Adults Expected to Work (Transitional/Temporary Programs)

| Program | Family Type | Maximum Support Allowance | Maximum Shelter Allowance | Maximum Total Benefit | Earnings Exemption | Claw-back Rate (Non-Exempt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC Temporary Assistancea | Single Adult | $385/month | $375/month | $760/month | $400/month (net earnings) | 100% |

| AB Alberta Worksb | Single Adult | $415/month | $330/month | $745/month | $230/month (net earnings) | 75% |

| SK SISc | Single Adult | $285/month | $575/month (Saskatoon/Regina) | $860/month | $325/month (gross earnings) | 100% |

| MB EIAd | Single Adult | $195/month | $576/month | $771/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 70% |

| ON Ontario Workse | Single Adult | $343/month | $390/month | $733/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 50% |

| QU Social Assistancef | Single Adult | $655/month + 20/month + $35/month | — | $710/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 100% |

| NS IAg | Single Adult | — | — | $586/month | $250/month (net earnings) | 25% from $250–$500, 50% from $500–$750, 75% over $750 |

| NB Transitional Assistance h | Single Adult | — | — | $564/month | $150/month (gross earnings) | 70% |

| PEi | Single Adult | $342 (food) + $24 (clothing) + $15 (household) + $19 (personal) | $588/month | $988/month | $250/month (net earnings) | 70% |

| NLj | Single adult | $534/month | $372/month | $906/month | $70/month (net earnings) | 80% |

| YTk | Single adult | Nov.–Mar.: $242 (food) + $459 (fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) Apr., May, Oct.: $242 (food) + $402(fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) June–Sept.: $242 (food) + $344 (fuel/utilities) + $74 (clothes) + $53 (incidentals) (Whitehorse) | $514 | Nov.–Mar.: $1,342/month Apr., May, Oct.: $1,285/month June–Sept.: $1,227/month | $0/month | 50% if within first 3 years or after 5 years of unemployment, 25% otherwise |

| NTl | Single adult | $343 (food) + $79 (clothes) (Yellowknife) | Actual cost of shelter + fuel + utilities. From CMHC: $1,517 m (average for 1-bedroom) | $1,939/month | $200/month (net earnings) | 85% |

Note: All values are for single adults expected to work who rent/own their own accommodation.

Source: CMHC Rental Market Report (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2020).

Current to May 2020. Source: Income and Employment Supports Policy Manual, (Alberta 2019).

Current to April 2020. Source: SIS webpage (Saskatchewan 2020).

Current to 2019. Source: Manitoba Assistance Regulation (Manitoba 2019).

Source: Ontario Works Policy Directives (Ontario n.d.).

Source: Individual and Family Assistance Regulation, Chapter VII (Quebec 2020).

Current to 27 November 2019. Employment Support and IA Regulations (Nova Scotia 2019).

Current to May 2020. Source: General Regulation, NB Reg 95-61 (New Brunswick 2020).

Current to January 2020. Source: email inquiry to Hannah Bell, MLA and Social Assistance Act Regulations (Legislative Assembly of Prince Edward Island 2019).

Source: Social assistance website (Newfoundland and Labrador 2020) and Income and Employment Support Policy and Procedure Manual, Chapter 3: Assessment of Income (Newfoundland and Labrador 2018).

Source: Social Assistance Regulation, O.I.C. 2012/83 (Yukon 2012).

Source: Income Assistance Regulations R.R.N.W.T. 1990, c. S-16 (Northwest Territories 2019).

Source: CMHC Rental Market Report (Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation 2020).

Notes

Alberta has partially exempted the CERB, British Columbia has fully exempted the CERB, and Saskatchewan has not exempted the CERB. More on this below.

This paper focuses on CERB as it was implemented on 6 April 2020, including the amendment on 15 April 2020. On 16 June 2020, the federal government announced that the CERB will be extended for an additional eight weeks, for a total of 24 weeks (Press 2020).

This may change. Bill C-17 is currently in its first reading, and in it are amendments to the Act that would penalize (through fines and/or incarceration) those who fraudulently received the CERB.

See Tables A.1 and A.2 in the Appendix for a comparison of earnings exemption thresholds by province and program.

The MBM is not available for the territories.

This is regardless of the rent deferral and eviction moratorium imposed by the provinces. Even if a low-income household is deferring rent today, it will still have to pay all the back rent when the moratorium is lifted. Low-income households that have to defer rent may still not be able to pay rent when the moratorium is lifted, resulting in their immediate eviction. Thus, they may choose to move now so that any rent they do owe will be less and/or to avoid hostile relations. Further, they may be bullied by their landlords today if they fail to pay rent, forcing them to move.

Contributor Information

Gillian Petit, Department of Economics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Lindsay M. Tedds, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta

References

- Alberta . 2019. Alberta Works Policy Manual. Accessed 23 May 2020 at http://www.humanservices.alberta.ca/AWOnline/index.html.

- Alberta . 2020. AISH Policy Manual. Accessed 24 May 2020 at http://www.humanservices.alberta.ca/AWOnline/AISH/7180.html.

- Bania, N., and Leete L.. 2007. Income Volatility and Food Insufficiency in US Low-Income Households, 1992–2003. Institute for Research on Poverty. Available https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp132507.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Boessenkool, K. 2020. Three Ways to Treat CERB in Social Assistance. C.D. Howe Institute. Accessed 2 June 2020 at https://www.cdhowe.org/intelligence-memos/boessenkool-robson-–-thoughts-forestalling-coming-childcare-crisis. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia . 2020. BCEA Policy & Procedure Manual, ed. Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction . Accessed 25 May 2020 at https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/policies-for-government/bcea-policy-and-procedure-manual.

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation . 2020. Rental Market Report Data Tables. Accessed 31 May 2020 at https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/data-and-research/data-tables/rental-market-report-data-tables.

- Falvo, N. 2015. “Three Essays on Social Assistance in Canada: A Multidisciplinary Focus on Ontario Singles.” PhD thesis, School of Public Policy & Administration, Carleton University. Accessed 20 June 202 at https://curve.carleton.ca/system/files/etd/2790f685-680f-419e-93a5-90cf54ed8e85/etd_pdf/4896234423e115ac1c9f6eea81ca8d73/falvo-threeessaysonsocialassistanceincanadaamultidisciplinary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian, L., and Shafir E.. 2015. “The Persistence of Poverty in the Context of Financial Instability: A Behavioral Perspective.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 34(4):1–33. 10.1002/pam.21854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian, L., Wolf S., Hill H., and Morris P.. 2015. “Intrayear Household Income Dynamics and Adolescent School Behaviour.” Demography 52(2):455–83. 10.1007/s13524-015-0370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Assembly of Prince Edward Island . 2019. Creation of a Special Committee of the Legislative Assembly on Poverty in PEI. Accessed 2 June 2020 at https://www.assembly.pe.ca/committees/current-committees/special-committee-on-poverty-in-pei.

- Loopstra, R., Dachner N., and Tarasuk V.. 2015. “An Exploration of the Unprecedented Decline in the Prevalence of Household Food Insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007 –2012.” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de politiques 41(3):191–206. 10.3138/cpp.2014-080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba . 2019. The Manitoba Assistance Act, 1988: Assistance Regulation, 404/88R. Accessed 2 June 2020 at https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/statutes/ccsm/a150e.php.

- McIntyre, L., Dutton D.J., Kwok C., and Emery J.C.H.. 2016. “Reduction of Food Insecurity among Low-Income Canadian Seniors as a Likely Impact of a Guaranteed Annual Income.” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de politiques 42(3):274–86. 10.3138/cpp.2015-069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, L., Patterson P.B., Anderson L.C., and Mah C.L.. 2016. “Household Food Insecurity in Canada: Problem Definition and Potential Solutions in the Public Policy Domain.” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de politiques 42(1):83–93. 10.3138/cpp.2015-066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- New Brunswick . 2020. New Brunswick Regulation under the Family Income Security Act, NB Reg 95–61. Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/social_development/policy_manual.html.

- New Brunswick . n.d. Social Development Policy Manual: Special Benefits. Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/social_development/policy_manual/benefits/content/special_benefits.html.

- Newfoundland and Labrador . 2018. Income and Employment Support Policy and Procedure Manual. Accessed 12 June 2020 at https://www.gov.nl.ca/aesl/files-policymanual/policymanual-pdf-is-assess-exempt-income.pdf.

- Newfoundland and Labrador . n.d. Program Overview. Accessed 12 June 2020 at https://www.gov.nl.ca/aesl/income-support/overview/#monthlyrates.

- Northwest Territories . 2019. Income Assistance Regulations, R.R.N.W.T. 1990, c.S-16. Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/social-assistance/social-assistance.r1.pdf.

- Nova Scotia . 2019. Employment Support and IA Regulations, NS Reg 195/2019. Accessed 4 June 2020 at https://novascotia.ca/just/regulations/regs/esiaregs.htm.

- Ontario . 2018a. Ontario Disability Support Program—Income Support. Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/odsp/income_support/index.aspx.

- Ontario . 2018b. Ontario Disability Support Program—Social Assistance Policy Directives: Income Support. Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/directives/index.aspx.

- Ontario . n.d. Social Assistance Policy Directives: Ontario Works, ed. Ministry of Community and Social Services . Accessed 3 June 2020 at https://www.mcss.gov.on.ca/en/mcss/programs/social/directives/index.aspx.

- Petit, G., and Tedds L.M.. 2020. Programs-Based Overview of Income and Social Support Programs for Working-age Persons in British Columbia. School of Public Policy, University of Calgary. [Google Scholar]

- Press, J. 2020. “CERB to Be Extended by 8 Weeks, Trudeau Announces.” Financial Post, 16 June 2020. Accessed 19 June 2020 at https://business.financialpost.com/news/economy/cerb-extended-eight-weeks.

- Prince Edward Island . 2018. Social Assistance Act Regulations. Accessed 2 June 2020 at https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/legislation/S%2604-3G-Social%20Assistance%20Act%20Regulations.pdf.

- Quebec . 2020. Individual and Family Assistance Regulation, Chapter A-13.1.1, r. 1. Accessed 4 June 2020 at http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cr/A-13.1.1,%20r.%201.

- Robson, J. 2008. Wealth, Low-Wage Work, and Welfare: The Unintended Costs of Provincial Needs Tests. Accessed 29 May 2020 at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0f8b/84982041f4e3a27c2a45d6650b1171ab5af8.pdf.

- Rothwell, D., and Robson J.. 2018. “The Prevalence and Composition of Asset Poverty in Canada: 1999, 2005, and 2012.” International Journal of Social Welfare 27(1):17–27. 10.1111/ijsw.12275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saskatchewan . 2014. The Saskatchewan Assistance Regulations, RRS c S-8 Reg 12. Accessed 2 June 2020 at https://www.canlii.org/en/sk/laws/regu/rrs-c-s-8-reg-12/latest/rrs-c-s-8-reg-12.html.

- Saskatchewan . 2020. Saskatchewan Income Support (SIS): Financial Help. Accessed 4 June 2020 at https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/family-and-social-support/financial-help/saskatchewan-income-support-sis.

- Schneider, D., and Harknett K.. 2017. Income Volatility in the Service Sector: Contours, Causes and Consequences. The Aspen Institute. Accessed 29 May 2020 at https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2017/07/ASPEN_RESEARCH_INCOME_VOLATILITY_WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, J. 2020. “How Ottawa Stopped Provincial CERB Clawbacks.” The Record, 29 April 2020. Accessed 23 May 2020 at https://www.therecord.com/opinion/contributors/2020/04/29/how-ottawa-stopped-provincial-cerb-clawbacks.html.

- Statistics Canada . 2020a. The Daily—Labour Force Survey, May 2020. Accessed 24 May 2020 at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200605/dq200605a-eng.htm.

- Statistics Canada . 2020b. “Monthly Average Retail Prices for Food and Other Selected Products.” Table 18-10-0002-01. Accessed 4 June 2020 at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000201.

- Statistics Canada . 2020c. Table 11-10-0066-01 Market Basket Measure (MBM) Thresholds for the Reference Family by Market Basket Measure Region, Component and Base Year. Accessed 4 June 2020 at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110006601.

- Statistics Canada . n.d. SPSD/M Product Overview. Ottawa. Accessed 14 May 2020 at http://odesi2.scholarsportal.info/documentation/FINBUS/SPSD/V18.1/DOCS/spsdm-bdmsps-overview-vuedensemble-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tweddle, A., and Aldridge H.. 2019. Welfare in Canada 2018. Maytree. Accessed 18 May 2020 at twwedhttps://maytree.com/welfare-in-canada/. [Google Scholar]

- Tweddle, A., and Stapleton J.. 2020. Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) Interactions with Provincial and Territorial Social Assistance and Subsidized Housing Programs and Youth Aging Out of Care. Maytree. Accessed 10 June 2020 at https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Backgrounder-CERB-interactions-8June2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, W.J., Linver M., and Brooks-Gunn J.. 2002. “How Money Matters for Young Children’s Development: Parental Investment and Family Process.” Child Development 73(6):1861–79. 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukon . 2012. Social Assistance Regulation, O.I.C. 2012/83. Accessed 2 June 2020 at http://www.gov.yk.ca/legislation/regs/oic2012_083.pdf.