Abstract

Trypanosomatids of the subfamily Strigomonadinae bear permanent intracellular bacterial symbionts acquired by the common ancestor of these flagellates. However, the cospeciation pattern inherent to such relationships was revealed to be broken upon the description of Angomonas ambiguus, which is sister to A. desouzai, but bears an endosymbiont genetically close to that of A. deanei. Based on phylogenetic inferences, it was proposed that the bacterium from A. deanei had been horizontally transferred to A. ambiguus. Here, we sequenced the bacterial genomes from two A. ambiguus isolates, including a new one from Papua New Guinea, and compared them with the published genome of the A. deanei endosymbiont, revealing differences below the interspecific level. Our phylogenetic analyses confirmed that the endosymbionts of A. ambiguus were obtained from A. deanei and, in addition, demonstrated that this occurred more than once. We propose that coinfection of the same blowfly host and the phylogenetic relatedness of the trypanosomatids facilitate such transitions, whereas the drastic difference in the occurrence of the two trypanosomatid species determines the observed direction of this process. This phenomenon is analogous to organelle (mitochondrion/plastid) capture described in multicellular organisms and, thereafter, we name it endosymbiont capture.

Keywords: genome, bacterial endosymbionts, Trypanosomatidae, Angomonas

1. Introduction

The flagellates of the family Trypanosomatidae are well known for human pathogens, such as Trypanosoma brucei, T. cruzi, and various Leishmania spp., yet the majority of trypanosomatid genera are intestinal parasites of insects [1]. In the process of adaptation to this omnipresent and extremely diverse group of hosts, trypanosomatids acquired many peculiar features, the study of which illuminated not only the evolution of parasitism in this group, but also the evolutionary strategies of eukaryotes in general [2,3]. One of the most intriguing phenomena is the presence of bacteria in the cytoplasm of some of these flagellates [4]. Such symbiotic relationships originated in trypanosomatids several times independently and range from recently established and unstable ones to those that demonstrate a high level of integration [5,6,7,8]. Mutualistic nature of these endosymbioses is demonstrated by the metabolic cooperation between the bacteria and their trypanosomatid hosts, removing the dependence of the latter on the environmental availability of essential nutrients, such as heme, some amino acids, and vitamins [9,10,11,12].

The first discovered and, consequently, most studied group of endosymbiont-bearing trypanosomatids is the subfamily Strigomonadinae, comprising seven described species of the genera Angomonas, Strigomonas, and Kentomonas [7,13]. All of these species have intracytoplasmic bacteria Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium spp. belonging to the family Alcaligenaceae (Betaproteobacteria: Burkholderiales), and, as judged by their respective phylogenies, the origin of the endosymbiosis was a single event followed by a prolonged coevolution [14]. However, the description of Angomonas ambiguus revealed a violation of the co-speciation pattern: being a sister species to A. desouzai, this flagellate contained an endosymbiont not discernible from that of Angomonas deanei by the sequences of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene and the internal transcribed spacer [7]. This discrepancy was reflected in the name of the described trypanosomatid (meaning “ambiguous” in Latin). The endosymbionts of both A. deanei and A. ambiguus were classified into a single species, Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium crithidii [7]. When the same discordance was later shown in the phylogenies of trypanosomatids and their endosymbionts based on the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene, it was proposed that A. ambiguus obtained its endosymbiont from A. deanei by horizontal transfer [15].

In this work, we address these complex evolutionary relationships by analyzing the genomic sequences of two strains of A. ambiguus and their respective endosymbionts from geographically distant locations (Brazil and Papua New Guinea) using comparative genomic and phylogenetic tools. Our results not only confirm the transition of bacteria between the two Angomonas species, but also demonstrate that this was not a singular event.

2. Results

2.1. Genomic Sequences

The assemblies for the trypanosomatid hosts of the strains TCC2435 and PNG-M02 consisted of 7753 (N50 = 22.5 kb) and 1740 contigs (N50 = 133.9 kb), with total lengths of 21.2 Mb and 23.7 Mb being similar to those of Angomonas spp. genomes (21–24 Mb) sequenced previously [16,17].

The genome assembly for the endosymbiont of Angomonas ambiguus TCC2435 (hereafter referred to as TCC2435 symbiont) contained 14 contigs with the total size of 803,474 bp and N50 of 126 kb. However, the contigs 8 and 12, comprising the ribosomal operon (~5.6 kb) and the EF-Tu gene (~1.2 kb), respectively, displayed a significantly higher coverage (Table S1) suggesting that they were present in more than one copy. Given that in the genomes of Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. the first sequence invariantly has 3 copies and the second one has 2 (except for the very divergent Ca. K. sorsogonicusi), we estimate that the actual genome size should be bigger by at least 12.4 kb, i.e., ~816 kb. A similar genome length was obtained for Ca. K. crithidii from A. ambiguus PNG-M02 (hereafter referred to as PNG-M02 symbiont), the assembly of which contained a single scaffold of 816,901 bp. These values are smaller than that for the genome of the endosymbiont of A. deanei TCC036E (821,930 bp; hereafter referred to as TCC036E symbiont) used here as a reference, but are within the known size range for the genomes of bacteria from Angomonas spp. and Strigomonas spp. (810–830 kb) [16,17].

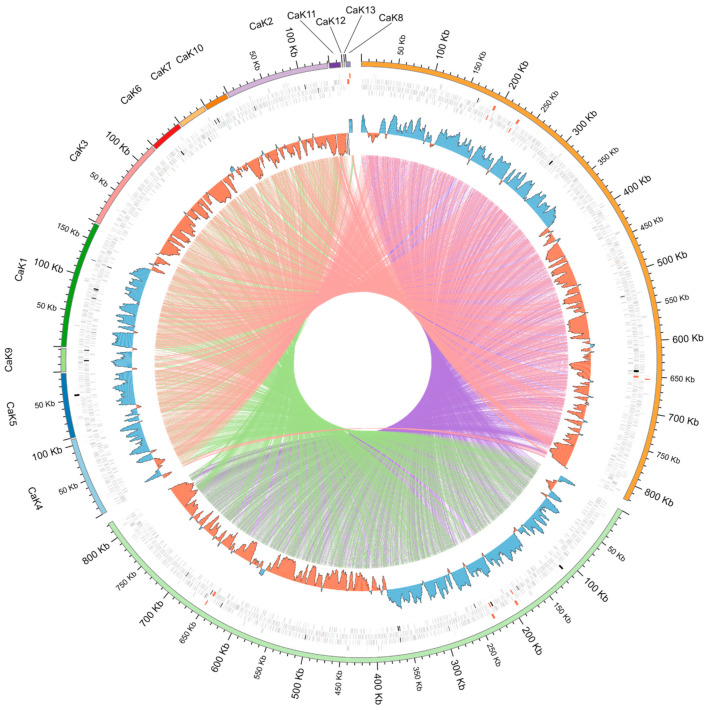

The GC content of the genomes of the PNG-M02 and ATCC2435 symbionts was 30.33% and 30.65%, respectively. These values are very close to those for the genomes of Ca. K. crithidii ATCC036E (30.96%) and the symbionts from Strigomonas spp. (31.23–32.55%) [16]. Similarly to other Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. [16,18] and bacterial endosymbionts in general [19,20], Ca. K. crithidii from A. deanei and the two A. ambiguus strains showed a very high level of gene order conservation with no detectable rearrangements (Figure 1 and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the genomes of three Ca. K. crithidii strains. The rings in the outside-in direction mean: (i) genomic coordinates of scaffolds; (ii) predicted genes (protein-coding in grey, rRNA in red, tRNA in blue, tmRNA in orange, ncRNA in green, and pseudogenes in black); (iii) GC skew plot (negative values in red and positive ones in blue). The lines in the central area connect orthologous genes between the genomes in a pairwise manner.

The overall genome sequence identity in the TCC2435/TCC036E, TCC2435/PNG-M02, and PNG-M02/TCC036E pairs was 90.8%, 90.4%, and 90.3%, respectively. These values are much higher than the interspecific similarity between the genomes of Strigomonas spp. symbionts (83–85%) or Ca. K. crithidii and Ca. K. desouzaii (73%) [16]. In agreement with the smaller size, the two bacterial genomes studied here were predicted to code for slightly smaller numbers of proteins: 729 and 726 for TCC2435 and PNG-M02 symbionts, respectively, as compared to 733 for the TCC036E symbiont (Table S2). However, the number of annotated pseudogenes in the two newly sequenced genomes was higher, with most of such sequences being frameshifted (Table S2). The distribution of the pseudogenes did not show any hotspots (Figure 1). Only 39 tRNA genes were predicted in the TCC2435 symbiont genome (which may be due to assembly fragmentation), whereas the genomes of PNG-M02 and TCC036E symbionts featured 43 and 44 such genes, respectively. The inspection of the tRNA lists for the three genomes revealed that they all differed from each other, but the differences consisted only in the number of redundant tRNAs, i.e., those with the same anticodon (Table S3).

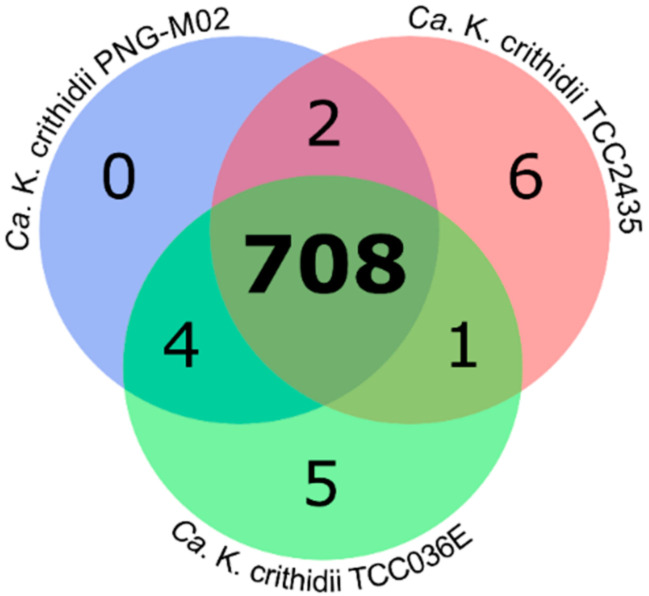

2.2. Analysis of Orthologous Groups (OGs) of Proteins

Only minor differences in gene content were revealed between the three analyzed endosymbiont genomes (Figure 2). The number of OGs present or absent only in one of the three genomes negatively correlated with the assembly quality, suggesting that at least some of the differences may be artifactual. Thus, the genome of the PNG-M02 symbiont assembled to a single contig based on PacBio and Illumina reads displayed the lowest numbers, whereas those for the fragmented assembly of the TCC2435 symbiont were the highest (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sharing of orthologous groups of proteins encoded in the genomes of the three Ca. K. crithidii strains.

A detailed inspection of the “unique” genes revealed that most of them either represent pseudogenes with a degraded sequence, which leads to clustering them into separate OGs, or potentially spurious short ORFs with no BLAST hits in NCBI nr database (Table S4). After exclusion of annotated or suspected pseudogenes and sequences with no BLAST hits, only two “unique” genes remained, both in the TCC036E symbiont genome: a helix-turn-helix domain-containing protein and tetraacyldisaccharide 4′-kinase. Each of these two genes is present (but not invariably) in other Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp., suggesting their dispensability. The first one, appearing to be a transcription factor (based on blast results), is absent from the genomes of endosymbionts of all Strigomonas spp. The second gene codes for an enzyme phosphorylating a precursor of lipopolysaccharide (component of the outer membrane) and is absent from the genomes of Ca. K. galatii and Ca. K. oncopelti. This agrees with the previous observation that the functional category “cell wall, membrane, and envelope biogenesis” is overrepresented among lost and pseudogenized genes in the genomes of Strigomonadinae symbionts [16]. Similar results were obtained after the inspection of the OGs missing from one of the three genomes: most of them were associated with the synthesis of the cell wall or lipopolysaccharide (Table S4). In addition, the ribosome-associated translation inhibitor RaiA (also absent from the genomes of endosymbionts of all Strigomonas spp.) was not detected in the TCC036E symbiont genome, and a short hypothetical protein was absent from the genome of TCC2435 symbiont, although a potential homolog could be detected with an increased e-value threshold (Table S4).

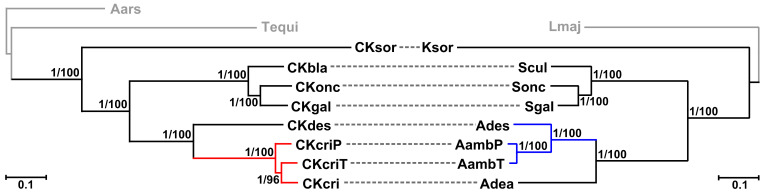

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

For each of the two phylogenomic datasets used (431 and 1549 single-copy genes for bacteria and trypanosomatids, respectively), maximum-likelihood and Bayesian trees showed identical topology with all branches or all but one bearing maximal statistical supports (Figure 3). In accordance with the previous inferences, Kentomonas sorsogonicus represents here the earliest branch within the subfamily Strigomonadinae [13], whereas its bacterium, Ca. K. sorsogonicusi, occupies the same position among the endosymbionts of this trypanosomatid subfamily [18]. The relationships within the genus Strigomonas and their respective endosymbionts are also correlated, suggesting cospeciation of these two groups of organisms. The situation is different for the third genus of Strigomonadinae: although Angomonas ambiguus and A. desouzai represent sister taxa, the bacteria hosted by the former species are paraphyletic in respect to that of A. deanei (Figure 3). This suggests a single horizontal endosymbiont transfer from A. ambiguus to A. deanei, in contrast to the previous proposal that the transfer had the opposite direction [15]. The alternative explanation of this figure implies two independent endosymbiont switches from A. deanei to A. ambiguus and is less parsimonious.

Figure 3.

Juxtaposed maximum-likelihood phylogenomic trees of endosymbiotic bacteria and their respective trypanosomatid hosts. Outgroups are shown in grey. Dashed lines connect endosymbionts with their hosts, while colored branches point to the discrepancy between their phylogenies. Numbers at branches indicate bootstrap support and Bayesian posterior probability values, respectively. Scale bars show the number of substitutions per site. Organism codes: Lmaj, Leishmania major; Ksor, Kentomonas sorsogonicus; Scul, Strigomonas culicis; Sonc, S. oncopelti; Sgal, S. galati; Ades, Angomonas desouzai; AambP and AambT, A. ambiguus strains PNG-M02 and TCC2535, respectively; Adea, A. deanei; Aars, Achromobacter arsenitoxydans; Tequi, Taylorella equigenitalis; CKsor, Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium sorsogonicusi; CKbla, Ca. K. blastocrithidii; CKonc, Ca. K. oncopeltii; CKgal, Ca. K. galatii; CKdes, Ca. K. desouzaii; CKcri, CKcriP, and CKcriT, Ca. K crithidii TCC036E, PNG-M02, and TCC2435, respectively.

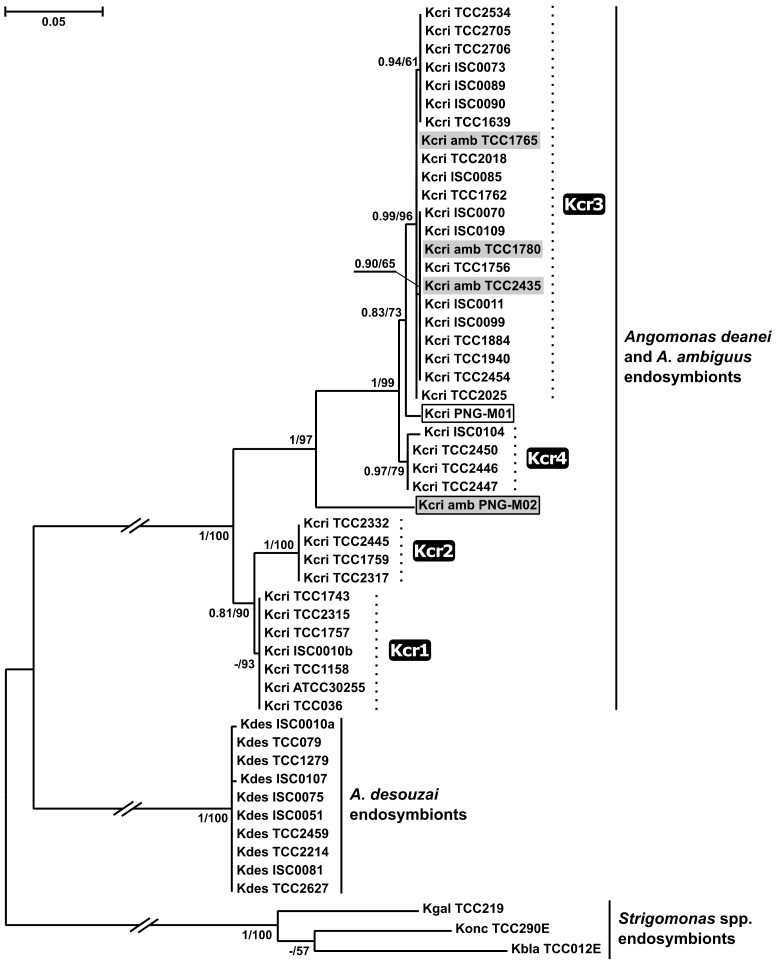

In order to clarify the situation, we performed an additional phylogenetic analysis using GAPDH gene sequences of Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. This allowed investigating the relationships of these bacteria on a much larger set of strains, available from a previous study [15]. The phylogenetic trees inferred using maximum likelihood and Bayesian approaches displayed almost identical topologies differing only in the presence of a single very short branch with a very short length (Figure 4). They were congruent with the previously published GAPDH tree [15] and confirmed the unity of the symbionts from A. deanei and A. ambiguus, representing the same four subclades (Kcr1–Kcr4). As in the previous inference, all sequences of the endosymbionts from A. ambiguus from Brazil (isolates TCC1765, TCC1780, and TCC2435) nested within the Kcr3 subclade and displayed 100% identity to some sequences of the endosymbionts from A. deanei originating from the same country. However, Ca. K. crithidii from the Papuan A. ambiguus isolate PNG-M02 represented a separate lineage, sister to the KCr3+Kcr4 group. The identity of its GAPDH sequence to those of other Ca. K. crithidii was only ~91%, almost the same as the observed minimum within this bacterial species (90.8%). Interestingly, the endosymbiont of A. deanei PNG-M01, obtained from the same host species and the same locality as PNG-M02, was not related to the latter and nested within the KCr3 + Kcr4 group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

GAPDH-based maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. The endosymbionts of Angomonas ambiguus are highlighted in grey, the isolates from Papua New Guinea are boxed. The labels in black rectangles indicate individual subclades of Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium crithidii. Numbers at branches indicate bootstrap supports and Bayesian posterior probabilities, respectively. Scale bar show the number of substitutions per site. The tree is rooted with the sequences of Strigomonas spp. endosymbionts.

3. Discussion

Mutualistic endosymbioses of prokaryotes with eukaryotes are quite diverse in terms of involved taxa, time of origin, and level of interdependence, with the latter two factors usually being correlated: evolutionary older relationships demonstrate a higher level of integration [21]. In insects, whose relationships with prokaryotes have been studied quite intensively, symbionts permanently residing in the cytoplasm of the host cells usually display perfect co-evolutionary patterns in contrast to bacteria that do not have such a restriction and, therefore, can switch hosts and/or be replaced by other species [22]. In agreement with this trend, Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. also show cospeciation with their trypanosomatid hosts and the only exception concerns the A. deanei–A. ambiguus pair, which shares a single endosymbiotic bacterium, Ca. K. crithidii. This was first detected using 16S rRNA gene sequences [7] and later confirmed by the analysis of bacterial GAPDH gene sequences [15].

Although being a rare phenomenon, the replacement of permanent endosymbionts is well known in insects [22] and presumably also occurs in ciliates [23,24]. The new bacterium in such a case originates from either a free-living or a facultatively symbiotic species and restores deteriorated functions of the old endosymbiont, whose genome degraded due to Muller’s ratchet [25]. The situation with the bacteria of Angomonas spp. is drastically different: both of them represent equally ancient endosymbionts and the replacement is combined with horizontal transfer between two related host species. This may appear unprecedented, but only when considering typical bacterial endosymbionts. A remarkable analogy can be found in mitochondria and plastids, the two kinds of organelles with prokaryote ancestry. The organellar capture (replacement of a mitochondrion or plastid of one species by that of another) also known as mitochondrial/plastid introgression (when it refers to genomes) has been described in a wide range of animals and plants and is usually associated with the formation of a hybrid zone between two species [26,27]. These species often have significantly different abundance levels resulting in asymmetrical introgression due to the contrast effects of genetic drift on small and large populations [28]. In general, introgression is driven by the prevalence of interspecific gene flow over the intraspecific one. In the case of mitochondria, this condition is met when dispersal is exerted predominantly by males (in some animals) or pollen (in conifers), not contributing the organelle to the progeny (due to maternal inheritance) and, thus, the intraspecific organellar gene flow for the colonizing species is close to zero [29,30].

Since the outcome of the interspecific interaction between A. deanei and A. ambiguus is similar to organellar capture, henceforth we will refer to it as endosymbiont capture. In order to understand the mechanism of this phenomenon, we summarize here the available data.

Out of the three Angomonas spp. described to date, A. deanei has the highest prevalence and the widest (potentially cosmopolitan) distribution. It was documented in various countries of Africa and South America, as well as in Papua New Guinea, Turkey, Czechia, and Russia [15,31,32]. Meanwhile, South America is currently the only known area for A. desouzai, whereas A. ambiguus, the rarest of the three species, has been also reported from Africa and Papua New Guinea [15,31,32]. All three species occur mostly in blowflies (Calliphoridae), although two clades of A. deanei apparently prefer Muscidae [15]. While it is unclear whether the single records of A. deanei and A. desouzai from Syrphidae [7] represent nonspecific infections, the first isolate of A. deanei from the predatory bug Zelus leucogrammus [33] undoubtedly is such a case [34].

Here, we sequenced and analyzed the genomes of Ca. K. crithidii from two A. ambiguus strains and compared them with the previously published genome of the endosymbiont from A. deanei TCC036E [16]. The three genomes display very similar sizes and GC content, a high level of nucleotide sequence identity and no significant differences in gene content. Based on these features, the three bacterial endosymbionts can be considered as members of a single species. Previously, the discussion of the discordance in the phylogenies of endosymbionts and their trypanosomatid hosts was based only on data concerning Brazilian strains, whereas here we also included those from a geographically distant area—Papua New Guinea. Our phylogenomic analysis confirmed the unity of the symbionts from A. deanei and A. ambiguus, but, due to the small number of included isolates, its results were inconclusive regarding the direction of the endosymbiont transfer. However, the phylogenetic analysis based on the bacterial GAPDH gene sequences allowed taking advantage of a larger Ca. K. crithidii sampling. It not only confirmed that the endosymbiont of A. deanei was captured by A. ambiguus but also demonstrated that this occurred more than once.

With little doubt, the occurrence of Angomonas spp. in the same blowfly hosts and the relatedness of the trypanosomatids are the factors that facilitate endosymbiont capture. It was demonstrated that A. deanei colonizes the host rectum and forms massive aggregates in the area of rectal papillae [32]. Presumably, upon mixed infections, cells of two different species may come into a close contact and attempt to undergo sexual process. In contrast to multicellular organisms, its successful completion is not required to create a new heritable nucleus-symbiont combination. Of note, a sex-independent (grafting-based) mechanism of chloroplast capture has been proposed for plants [35].

By analogy to organelle capture, the reported very low prevalence of A. ambiguus [15] explains the phenomenon to be observed as a unidirectional process with this species being an acceptor. The reason why only A. deanei but not A. desouzai, being more closely related to A. ambiguus, is observed as a donor may be also related to their relative abundance. However, we cannot exclude that this is just due to the small number of A. ambiguus strains analyzed to date. Importantly, the endosymbiont capture is a repeated process (there were at least two independent cases) and its incidence may depend on the local demographic situation. The identical GAPDH sequences of Ca. K. crithidii of A. ambiguus and several A. deanei strains from South America indicate a recent event in agreement with the data on the current drastically different prevalence of these two species in that area. Meanwhile, the sequences of this gene in the endosymbionts of the Papuan isolates of both trypanosomatid species obtained from the same population of blowflies were significantly different and positioned distantly on the phylogenetic tree. This might be a result of a relatively ancient endosymbiont capture. Regrettably, for the moment other isolates of these two species from Papua New Guinea and data on their prevalence in that region are not available.

In sum, the replacement of endosymbionts of Angomonas ambiguus by those of Angomonas deanei is a repeated process analogous to organelle capture described in multicellular organisms and apparently shares with the latter one of the underlying mechanisms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Trypanosomatid Strains: Origin and Cultivation

In this work, two axenically cultivated strains of Angomonas ambiguus were used: (i) PNG-M02 from the blowfly Chrysomya megacephala collected in Nagada, Papua New Guinea [31]; and (ii) TCC2435 representing a clonal culture of TCC1780 isolated from C. albiceps in Campo Grande, Brazil [7]. The cultures were maintained at 27 °C in RPMI 1640 cultivation medium at pH 7.0 supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 10 μg/mL of hemin, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin. In addition to cultures, DNA of the non-cultivated A. deanei strain PNG-M01 (from the same host species and location as PNG-M02) available from an earlier study [31] was used for PCR amplification of the bacterial GAPDH gene.

4.2. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

DNA extraction from both strains of A. ambiguus was performed by the classical phenol-chloroform method, without preceding separation of the endosymbiont and trypanosomatid cells. Sequencing of TCC2435 DNA was performed using Roche 454 GS-FLX Titanium (1.37 mln single-ended reads, 550 Mbp), and Illumina MiSeq (13 mln 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads) platforms. DNA of PNG-M02 strain was sequenced at Wellcome Sanger Institute using Illumina MiSeq and HiSeq 2500 technologies (2,4 mln 2 × 250 bp and 14.7 mln 2 × 125 paired-end reads, respectively) as well as PacBio RS II sequencing system (13,977 long reads, 321 Mbp). The corresponding raw reads are available from GenBank under the following accession numbers: ERS4809514 (PNG-M02) and SRR14208463, SRR14216068, SRR14216074, and SRR14209298 (TCC2435).

After processing the raw reads generated by Illumina and 454 platforms with Trimmomatic V. 0.39 [36] and those from the PacBio system with SMRT Analysis Suite (Pacific BioSciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), the data quality was assessed using the FastQC v. 0.11.9 software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc, accessed on 30 April 2020). Since the BLAST search against available genomic sequences of trypanosomatids revealed that the PNG-M02 sample was contaminated with DNA from Crithidia fasciculata, the data were filtered by mapping the preprocessed reads to the C. fasciculata genome Cf-C1 (TritrypDB v. 40) using BBmap v. 38.84 with the settings recommended for contaminant reads removal (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/, accessed on 6 May 2020). The genomic assembly for the PNG-M02 strain was made with hybridSPAdes v. 3.14.1 [37] using both Illumina and error corrected PacBio reads. The endosymbiont genome was identified using blastn and the closest known endosymbiont genome Ca. K. crithidii TCC036E. Two different assemblies were made for the strain TCC2435 with Newbler v. 2.7: (i) trypanosomatid-focused using only Illumina data (with “-large” option); and (ii) endosymbiont-focused using both 454 and Illumina reads. Genes were predicted with Companion [38] and Glimmer v. 3 [39] for the bacteria and their hosts, respectively. Gene annotation for the endosymbionts was performed with PROKKA v. 1.14.5 [40]. The assembled genome sequences have been deposited in GenBank under the Bioproject accession PRJNA673871.

4.3. Synteny Analysis of Bacterial Genomes

The single-scaffold genomic sequences of Ca. K. crithidii TCC036E (GCA_000340825.1) and Ca. K. crithidii PNG-M02 were circularized using Circlator v. 1.5.5 [41] and the dnaA gene was selected as a start in their linear representation. The scaffolds of Ca. K. crithidii TCC2435 genome were reordered and inverted to match the two abovementioned ones, following tripartite genome alignment and synteny analysis using Mauve v. 2015-02-13 [42]. Visualization of genomic alignment was prepared with Circos v. 0.69-9 [43].

4.4. Phylogenomic Analyses

Analyses of protein OGs were performed with OrthoFinder v. 2.3.11 [44] with the default settings. In addition to the sequences obtained in this work, the bacterial dataset (BD) comprised the previously published genomes of all six Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp. as well as those of Achromobacter arsenitoxydans and Taylorella equigenitalis, which were used here as outgroups (Table S5). The trypanosomatid dataset (TD) included previously published genomic sequences for Strigomonadinae and L. major Friedlin, which served as an outgroup (Table S5), as well as the generated earlier draft sequence of Kentomonas sorsogonicus [18]. Out of the total 1645 (BD) and 17,990 (TD) inferred protein OGs, 431 and 1549, respectively, included one protein per species and were used for the subsequent phylogenomic analyses. The amino acid sequences were aligned using Muscle v. 3.8.31 [45], trimmed with Gblocks v. 0.91b [46] and concatenated with FASconCAT-G v.1.04 [47]. The resulting supermatrices contained 133,474 (BD) and 658,788 (ED) positions with respective gap proportions of 0.4% and 5%. Maximum likelihood analyses were performed in RAxML v.8.2.11 [48] with automated selection of the substitution schemes for the partitioned model, linked edge lengths, and 100 bootstrap pseudoreplicates for branch support estimation. Bayesian inference was performed in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 [49] with “mixed” prior for amino acid substitution matrix and rate heterogeneity modelled using 4 discrete Γ-categories. Relative rates, substitution models, and Γ-distribution shape were unlinked across partitions. The analysis was run for 1,000,000 generations with every 100th tree sampled, and other parameters set by default.

4.5. Amplification and Phylogenetic Analysis of GAPDH Gene

The bacterial GAPDH gene of the strain PNG-M01 was amplified and sequenced using the newly designed primers KAGF1 (5′-ATTTTAAGAGCTCATTACGAAGGT-3′) and KAGR1 (5′-GATCTTGCCCTACGCAAATC-3′). The obtained sequence was deposited in GenBank under the accession number MW161049. Other sequences of this gene from the endosymbionts of Angomonas and Strigomonas available in the GenBank were collected (Table S6) and aligned with MAFFT v. 7.471 using L-INS-I algorithm [50]. Maximum Likelihood analysis was accomplished in IQ-TREE v. 2.0.5 [51] with the best substitution model (TIM2 + F + I) selected by the built-in ModelFinder [52]. The statistical support of branches was estimated by the standard bootstrap method with 1000 pseudoreplicates. Bayesian inference was accomplished in MrBayes v. 3.2.7 under the GTR + I model with run parameters as described above.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of our laboratories for the discussion of our results.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens10060702/s1, Figure S1: MAUVE alignment of three genomes of Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium spp., Table S1: Read coverage of the genomic contigs of the TCC2435 symbiont, Table S2: Summary statistics on the genes encoded in the three Ca. K. crithidii genomes, Table S3: Comparison of lists of tRNA genes in the genomes of endosymbionts from Angomonas spp., Table S4: Presence and absence of OGs in the genomes of Ca. K. crithidii, Table S5: Previously published genomic sequences used in the phylogenomic analyses, Table S6: GAPDH gene sequences from Ca. Kinetoplastibacterium sequences retrieved from GenBank for phylogenetic analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.P.A. and A.Y.K.; methodology, A.B., G.A.B., J.A.C., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; validation, A.B., G.A.B., J.A.C., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; formal analysis, T.S., A.B., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; investigation, T.S., A.C.M., J.R., M.G.S., M.S., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; resources, G.A.B., J.A.C., J.L., M.M.G.T., E.P.C., V.Y.; data curation, T.S., A.B., and J.M.P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.P.A. and A.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, V.Y., J.L., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; visualization, T.S., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; supervision, V.Y., J.L., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K.; funding acquisition, V.Y., J.L., G.A.B., J.A.C., J.M.P.A., and A.Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the European Regional Funds project “Centre for Research of Pathogenicity and Virulence of Parasites” CZ.02.1.01/16_019/0000759 to V.Y., A.Y.K., J.R., and J.L., the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (grant 20-07186S) to V.Y., J.L., and A.Y.K., State Assignment AAAA-A19-119031390116-9 for ZIN RAS to A.Y.K., São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) grants 2016/07487-0 (to M.M.G.T and E.P.C.) and 2013/14622-3 (to J.M.P.A.), CNPq fellowship to A.C.M., Wellcome Trust grant 206194 for M.S. and J.A.C., National Science Foundation’s Assembling the Tree of Life program to G.A.B. and M.G.S., and a grant from the University of Ostrava SGS/PrF/2021 for J.R. Computational resources were provided to T.S. by the project “e-Infrastruktura CZ” (e-INFRA LM2018140) within the program Projects of Large Research, Development and Innovations Infrastructures and ELIXIR-CZ project (LM2018131), part of the international ELIXIR infrastructure.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from GenBank under the following accession numbers: ERS4809514 (PNG-M02 raw reads), SRR14208463, SRR14216068, SRR14216074, and SRR14209298 (TCC2435 raw reads), Bioproject PRJNA673871 (generated assemblies).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kostygov A.Y., Karnkowska A., Votýpka J., Tashyreva D., Maciszewski K., Yurchenko V., Lukeš J. Euglenozoa: Taxonomy, diversity and ecology, symbioses and viruses. Open Biol. 2021;11:200407. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lukeš J., Butenko A., Hashimi H., Maslov D.A., Votýpka J., Yurchenko V. Trypanosomatids are much more than just trypanosomes: Clues from the expanded family tree. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:466–480. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butenko A., Hammond M., Field M.C., Ginger M.L., Yurchenko V., Lukeš J. Reductionist pathways for parasitism in euglenozoans? Expanded datasets provide new insights. Trends Parasitol. 2021;37:100–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maslov D.A., Opperdoes F.R., Kostygov A.Y., Hashimi H., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. Recent advances in trypanosomatid research: Genome organization, expression, metabolism, taxonomy and evolution. Parasitology. 2019;146:1–27. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganyukova A.I., Frolov A.O., Malysheva M.N., Spodareva V.V., Yurchenko V., Kostygov A.Y. A novel endosymbiont-containing trypanosomatid Phytomonas borealis sp. n. from the predatory bug Picromerus bidens (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) Folia Parasitol. 2020;67:4. doi: 10.14411/fp.2020.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostygov A.Y., Dobáková E., Grybchuk-Ieremenko A., Váhala D., Maslov D.A., Votýpka J., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. Novel trypanosomatid-bacterium association: Evolution of endosymbiosis in action. mBio. 2016;7:e01985-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01985-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teixeira M.M., Borghesan T.C., Ferreira R.C., Santos M.A., Takata C.S., Campaner M., Nunes V.L., Milder R.V., de Souza W., Camargo E.P. Phylogenetic validation of the genera Angomonas and Strigomonas of trypanosomatids harboring bacterial endosymbionts with the description of new species of trypanosomatids and of proteobacterial symbionts. Protist. 2011;162:503–524. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catta-Preta C.M., Brum F.L., da Silva C.C., Zuma A.A., Elias M.C., de Souza W., Schenkman S., Motta M.C. Endosymbiosis in trypanosomatid protozoa: The bacterium division is controlled during the host cell cycle. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:520. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostygov A.Y., Butenko A., Nenarokova A., Tashyreva D., Flegontov P., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. Genome of Ca. pandoraea novymonadis, an endosymbiotic bacterium of the trypanosomatid Novymonas esmeraldas. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1940. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein C.C., Alves J.M., Serrano M.G., Buck G.A., Vasconcelos A.T., Sagot M.F., Teixeira M.M., Camargo E.P., Motta M.C. Biosynthesis of vitamins and cofactors in bacterium-harbouring trypanosomatids depends on the symbiotic association as revealed by genomic analyses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves J.M., Klein C.C., da Silva F.M., Costa-Martins A.G., Serrano M.G., Buck G.A., Vasconcelos A.T., Sagot M.F., Teixeira M.M., Motta M.C., et al. Endosymbiosis in trypanosomatids: The genomic cooperation between bacterium and host in the synthesis of essential amino acids is heavily influenced by multiple horizontal gene transfers. BMC Evol. Biol. 2013;13:190. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alves J.M., Voegtly L., Matveyev A.V., Lara A.M., da Silva F.M., Serrano M.G., Buck G.A., Teixeira M.M., Camargo E.P. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of heme synthesis genes in trypanosomatids and their bacterial endosymbionts. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Votýpka J., Kostygov A.Y., Kraeva N., Grybchuk-Ieremenko A., Tesařová M., Grybchuk D., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. Kentomonas gen. n., a new genus of endosymbiont-containing trypanosomatids of Strigomonadinae subfam. n. Protist. 2014;165:825–838. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Y., Maslov D.A., Chang K.P. Monophyletic origin of beta-division proteobacterial endosymbionts and their coevolution with insect trypanosomatid protozoa Blastocrithidia culicis and Crithidia spp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8437–8441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borghesan T.C., Campaner M., Matsumoto T.E., Espinosa O.A., Razafindranaivo V., Paiva F., Carranza J.C., Añez N., Neves L., Teixeira M.M.G., et al. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of coevolving symbiont-harboring insect trypanosomatids, and their Neotropical dispersal by invader African blowflies (Calliphoridae) Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:131. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves J.M., Serrano M.G., Maia da Silva F., Voegtly L.J., Matveyev A.V., Teixeira M.M., Camargo E.P., Buck G.A. Genome evolution and phylogenomic analysis of Candidatus kinetoplastibacterium, the betaproteobacterial endosymbionts of Strigomonas and Angomonas. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013;5:338–350. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motta M.C., Martins A.C., de Souza S.S., Catta-Preta C.M., Silva R., Klein C.C., de Almeida L.G., de Lima Cunha O., Ciapina L.P., Brocchi M., et al. Predicting the proteins of Angomonas deanei, Strigomonas culicis and their respective endosymbionts reveals new aspects of the trypanosomatidae family. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva F.M., Kostygov A.Y., Spodareva V.V., Butenko A., Tossou R., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V., Alves J.M.P. The reduced genome of Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium sorsogonicusi, the endosymbiont of Kentomonas sorsogonicus (Trypanosomatidae): Loss of the haem-synthesis pathway. Parasitology. 2018;145:1287–1293. doi: 10.1017/S003118201800046X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Cano D.J., Reyes-Prieto M., Martinez-Romero E., Partida-Martinez L.P., Latorre A., Moya A., Delaye L. Evolution of small prokaryotic genomes. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:742. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wernegreen J.J. Endosymbiont evolution: Predictions from theory and surprises from genomes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015;1360:16–35. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wernegreen J.J. Endosymbiosis. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:R555–R561. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCutcheon J.P., Boyd B.M., Dale C. The life of an insect endosymbiont from the cradle to the grave. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:R485–R495. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boscaro V., Fokin S.I., Petroni G., Verni F., Keeling P.J., Vannini C. Symbiont replacement between bacteria of different classes reveals additional layers of complexity in the evolution of symbiosis in the ciliate Euplotes. Protist. 2018;169:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vannini C., Ferrantini F., Ristori A., Verni F., Petroni G. Betaproteobacterial symbionts of the ciliate Euplotes: Origin and tangled evolutionary path of an obligate microbial association. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;14:2553–2563. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett G.M., Moran N.A. Heritable symbiosis: The advantages and perils of an evolutionary rabbit hole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10169–10176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421388112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toews D.P., Brelsford A. The biogeography of mitochondrial and nuclear discordance in animals. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:3907–3930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsitrone A., Kirkpatrick M., Levin D.A. A model for chloroplast capture. Evolution. 2003;57:1776–1782. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison R.G., Larson E.L. Hybridization, introgression, and the nature of species boundaries. J. Hered. 2014;105(Suppl. 1):795–809. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esu033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit R.J., Excoffier L. Gene flow and species delimitation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009;24:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du F.K., Petit R.J., Liu J.Q. More introgression with less gene flow: Chloroplast vs. mitochondrial DNA in the Picea asperata complex in China, and comparison with other conifers. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:1396–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Týč J., Votýpka J., Klepetková H., Šuláková H., Jirků M., Lukeš J. Growing diversity of trypanosomatid parasites of flies (Diptera: Brachcera): Frequent cosmopolitism and moderate host specificity. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;69:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganyukova A.I., Malysheva M.N., Frolov A.O. Life cycle, ultrastructure and host-parasite relationships of Angomonas deanei (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) in the blowfly Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Protistology. 2020;14:204–218. doi: 10.21685/1680-0826-2020-14-4-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carvalho A.L.M. Estudos sobre a posição sistemática, a biologia e a transmissão de tripanosomatídeos encontrados em Zelus leucogrammus (Perty, 1834) (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) Rev. Pathol. Trop. 1973;2:223–274. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frolov A.O., Kostygov A.Y., Yurchenko V. Development of monoxenous trypanosomatids and phytomonads in insects. Trends Parasitol. 2021;37:538–551. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2021.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stegemann S., Keuthe M., Greiner S., Bock R. Horizontal transfer of chloroplast genomes between plant species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:2434–2438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antipov D., Korobeynikov A., McLean J.S., Pevzner P.A. hybridSPAdes: An algorithm for hybrid assembly of short and long reads. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1009–1015. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinbiss S., Silva-Franco F., Brunk B., Foth B., Hertz-Fowler C., Berriman M., Otto T.D. Companion: A web server for annotation and analysis of parasite genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W29–W34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delcher A.L., Bratke K.A., Powers E.C., Salzberg S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt M., De Silva N., Otto T.D., Parkhill J., Keane J.A., Harris S.R. Circlator: Automated circularization of genome assemblies using long sequencing reads. Genome Biol. 2015;16:294. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darling A.E., Mau B., Perna N.T. ProgressiveMauve: Multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emms D.M., Kelly S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuck P., Longo G.C. FASconCAT-G: Extensive functions for multiple sequence alignment preparations concerning phylogenetic studies. Front. Zool. 2014;11:81. doi: 10.1186/s12983-014-0081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Hohna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T.K.F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from GenBank under the following accession numbers: ERS4809514 (PNG-M02 raw reads), SRR14208463, SRR14216068, SRR14216074, and SRR14209298 (TCC2435 raw reads), Bioproject PRJNA673871 (generated assemblies).