Abstract

The valorization of agri-food by-products is essential from both economic and sustainability perspectives. The large quantity of such materials causes problems for the environment; however, they can also generate new valuable ingredients and products which promote beneficial effects on human health. It is estimated that soybean production, the major oilseed crop worldwide, will leave about 597 million metric tons of branches, leaves, pods, and roots on the ground post-harvesting in 2020/21. An alternative for the use of soy-related by-products arises from the several bioactive compounds found in this plant. Metabolomics studies have already identified isoflavonoids, saponins, and organic and fatty acids, among other metabolites, in all soy organs. The present review aims to show the application of metabolomics for identifying high-added-value compounds in underused parts of the soy plant, listing the main bioactive metabolites identified up to now, as well as the factors affecting their production.

Keywords: Glycine max, foodomics, agricultural waste

1. Introduction

1.1. Metabolomics Applied to Agri-Foods and Their By-Products

Plants have been used to produce food, feed, energy, biomaterials, and also as a source of bioactive compounds. Metabolomics has emerged as one of the principal contributors to enhancing the identification of these compounds, generating innovative discoveries and supporting the development of novel products [1]. Progress in efficient extraction techniques, such as ultrasound, microwave, and pulsed-electric-field-assisted extractions, as well as supercritical fluid and pressurized liquid extractions, among others, generate extracts with a higher yield and bioactivity [2,3,4,5,6]. Once these extracts are generated, they can be analyzed with one or more powerful chromatography and/or electrophoresis techniques coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), producing accurate chemical information on a vast number of compounds [7,8,9,10,11,12]. For the identification of metabolites, databases have been increasingly updated, crosslinking information from different libraries. Sorokina and Steinbeck [13] list almost one hundred databases useful for natural product research. In addition, Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) and Small Molecule Accurate Recognition Technology (SMART 2.0) are examples of bio-cheminformatics tools for the analysis of MS and NMR data, respectively [14,15,16]. All these modern techniques and tools support the advancement of metabolomics’ frontiers.

In 2019, 8.3 billion metric tons of cereals, oil crops, roots and tubers, sugar crops, and vegetables were produced [17]. However, it is estimated that one-third of food production is lost and wasted, and this problem is Target 12.3 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations (UN) [18,19,20]. In this context, foodomics has shown the potential not only of foods, but also of their related by-products, as sources of compounds with human health benefits (Figure 1) [21,22]. For example, Katsinas et al. [23] used supercritical carbon dioxide and pressurized liquid extractions to valorize olive pomace, which is a by-product of the olive oil industry. As a result, they identified several phenolic compounds and generated bioactive extracts. Assirati et al. [24] applied a metabolomics approach in the chemical investigation of the three major solid sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) by-products, leading to the identification of up to 111 metabolites in a single matrix, with several of these compounds already known by their potent bioactive properties, such as 1-octacosanol, octacosanal, orientin, and apigenin-6-C-glucosylrhamnoside. Terpenes of orange (Citrus sinensis) juice by-products showed antioxidant and neuroprotective potential in in vitro assays, as revealed by Sánchez-Martínez et al. [25]. As for the permeability of the blood–brain barrier, some terpenes of orange extract demonstrated a high capacity to cross this obstacle, which is a critical point for treating Alzheimer’s disease [25,26].

Figure 1.

Foodomics proposes a holistic approach to develop ingredients and products with health benefits from foods and their by-products.

1.2. Glycine max: More Than Beans

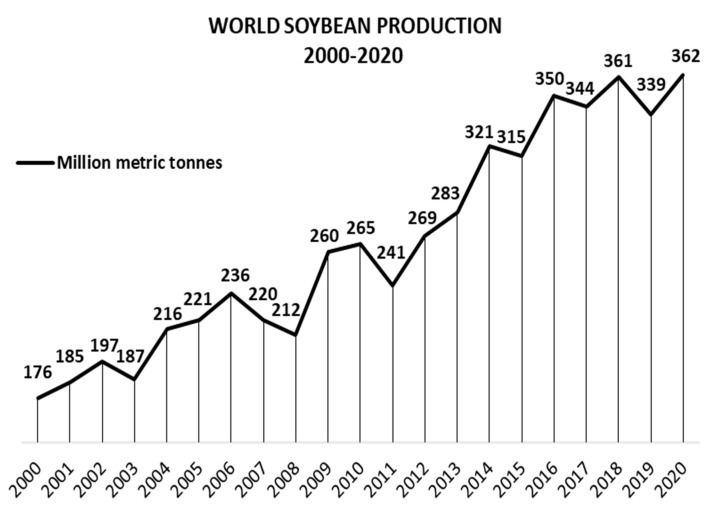

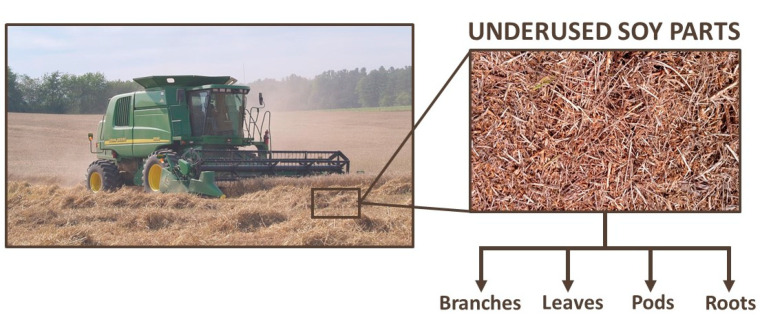

Soy, also known as soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), is originally from China and Eastern Asia [27]. It is the major oilseed crop worldwide, with a world production of 362, 254, and 61 million metric tons of soy grains, meal, and oil, respectively, in 2020/21. For the same period, the global area harvested was 1.28 million km2, 2.5 times the area of Spain [28,29]. Figure 2 shows soybean production from 2000/01 to 2020/21, demonstrating consistent growth, with few moments of decrease [29,30]. However, this production involves just one part of G. max: the beans. Krisnawati and Adie [31] analyzed 29 soybean genotypes and found an average value of 1.65 for the straw:grain ratio in soy. Therefore, it is estimated that about 597 million metric tons of soy branches, leaves, pods, and roots will be left on the ground post-harvesting in 2020/21 [29,31]. Figure 3 shows the soil of a no-tillage soybean production, a system which leaves all underused soy parts on the ground. Keeping these materials on the soil contributes to mineral, organic matter, and humidity factors [32]. In contrast, problems related to higher weed and disease infestations, as well as greenhouse gas emissions caused by the decomposition of organic matter, require alternative management of the agricultural straw [33,34,35,36,37,38]. By applying a biorefinery approach, such by-products could be transformed into raw material for the extraction of several bioactive compounds.

Figure 2.

World soybean production 2000–2020, in million metric tons.

Figure 3.

Underused soy parts left on the soil just after the soybean harvest.

Inspired by the potential of underused soy parts, this review aims to show the application of metabolomics in soy analysis, listing the potential of these by-products as a source of high-added-value compounds, as well as the factors which affect their production.

2. Metabolomics and Soy

An Overview

Soy has been recognized as a medicinal plant since it contains several bioactive compounds in its various parts. For example, bioactive peptides found in soybeans have been linked to human health benefits with potential anti-hypertensive, anti-cancer, and anti-inflammatory properties [39]. Another type of bioactive compound identified in soybeans, the anthocyanins, showed anti-obesity and anti- inflammatory properties [40]. Isoflavonoids, the best-known class of compounds found in all parts of soy, have been studied due to their potential protective effects associated with chronic diseases, cancer, osteoporosis, and menopausal symptoms [41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Different factors modulate a plant’s metabolism, and metabolomics can measure these variations qualitatively and quantitatively, analyzing the production and turnover of primary and secondary (specialized) metabolites [48,49,50]. In soy, metabolomics studies have identified four main causes of changes in metabolism: genetic modifications, organism interactions, growth stages, and abiotic factors. Genetic modifications can be related to different species and cultivar/variety of soybean. Lu et al. [51] investigated the metabolic changes between two soybean species (Glycine max and Glycine soja) under salt stress. Using gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and liquid chromatography coupled to Fourier transform and mass spectrometry (LC–FT/MS), the authors found a higher content of hormones, reactive oxygen species, and other substances related to the salt stress condition. In another study, Glycine max and Glycine gracilis presented different profiles of secondary metabolites during the growth stage, as revealed by a 1H NMR-based metabolomics approach [52]. The advancement of molecular biology provides the development of a wide range of soybean cultivars or varieties, with new types of plants resistant against insects, abiotic stress, and other factors. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) database reveals 4869 patents for a “soybean cultivar” or “soybean variety” search [53]. Different colored soybeans, such as brown, yellow, or black, present specific metabolite profiles [54,55,56]. Isoflavones could be the substrate for the production of proanthocyanidin in the seed coat, being a possible cause for the brown color of the cultivar Mallikong mutant [55]. Yang et al. [56] identified higher levels of anthocyanin and protein in yellow cotyledon seeds of black soybean. In contrast, higher levels of isoflavone, stearic acid, and polysaccharide are related to the green cotyledon seeds of the same species. Two Korean soy cultivars, Sojeongja and Haepum, presented different levels of soyasaponins Aa and Ab, whose production is related to specific gene variations [57]. Another important factor in genetic modification is the transgenic soybean. García-Villalba et al. [58] used capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOF-MS) to qualitatively and quantitatively measure the metabolites of transgenic and non-transgenic soybeans. In summary, similar types and amounts of metabolites were identified. The same result was achieved by Harrigan et al. [59] and Clarke et al. [60]. However, it is reported that transgenic soybeans were less affected by generational effects and can present more secondary metabolites, such as prenylated isoflavones [61,62].

Moreover, the interaction between soy and microorganisms, nematodes, aphids, and other insects causes distinct metabolic responses, and metabolomics is a unique approach for understanding such changes, providing insights to improve soy’s response against biotic factors [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. Recent works used GNPS to identify metabolite variation in soy infected by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi and the nematode Aphelenchoides besseyi [78,79,80]. Both pathogens resulted in a higher production of bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, isoflavonoids, and terpenoids.

Distinct metabolic responses have also been reported for each growth stage of soybean [81,82,83]. During germination, 58 metabolites were reported in the separation of soy sprouts, such as phytosterols, isoflavones, and soyasaponins [84]. The production of secondary metabolites such as daidzein, genistein, and coumestrol also changed in the vegetative and reproductive soybean stages, as described by Song et al. [85].

The presence of soybean crops in a wide range of latitudes and longitudes is a consequence of several adaptive changes in their metabolism. Brazil, which is the major producer of soybean, presents different soil and climate types; even so, there is soy production in all its regions. This fact corroborates the high performance of soybean in several abiotic conditions. In addition, treatments with fertilizers and other agricultural inputs have been tested for the cultivation of soybeans in unfavorable conditions, causing additional modifications in soy metabolism [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. As an example of external treatments, ethylene application on soybean leaves increased the genistin, daidzin, malonylgenistin, and malonyldaidzin production [94]. Using two ionization methods, electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI), coupled to Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance-mass spectrometry (FTICR-MS), Yilmaz et al. [95] analyzed the metabolite profile of soy leaves from midsummer to autumn. They found a decreased production of chlorophyll-related metabolites and a higher level of disaccharides from summer to autumn. Another metabolomic approach analyzed soy leaves from crops with different geographical localizations and identified different amounts of metabolites such as pinitol and flavonoids [96]. An excellent review performed by Feng et al. [97] summarizes the use of metabolomics in soy under abiotic stress.

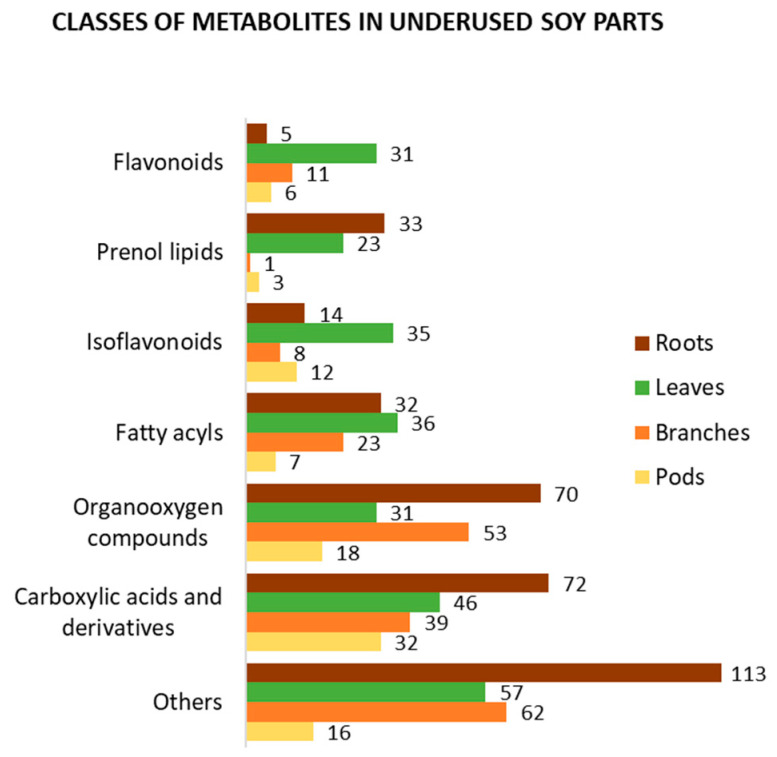

3. Bioactive Compounds in Underused Soy Parts

In addition to the four main causes of change in soy metabolism mentioned above, both qualitative and quantitative metabolic variations among soy organs are expected. To present an overview of the metabolite profile of underused soy parts, we selected metabolomics and related works which used various approaches to analyze them [38,67,78,79,80,93,94,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. Using Jchem (JChem for Excel 21.1.0.787, ChemAxon (https://www.chemaxon.com, accessed on 8 April 2021)) [109] and ClassyFire [110], we organized and classified the metabolites identified in soy roots, leaves, branches, and pods, as presented in Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S4, respectively. Figure 4 summarizes the best-known classes of bioactive compounds identified in underused soy parts. Carboxylic acids and their derivatives, such as amino acids, peptides, and analogues, are the most mentioned class of compounds. This class is mainly composed of primary metabolites; however, it also contains several bioactive compounds. Similarly, organooxygen and fatty acyl compounds include metabolites with human health benefits. Isoflavonoids, which are the most mentioned class of secondary metabolites, as well as prenol lipids and flavonoids, have been suggested to have a wide range of medicinal uses. Focusing on secondary metabolites, prenol lipids are the most identified class of compounds in soy roots, with several soyasaponins found in this part. In soy leaves, different subclasses of isoflavonoids have been found, such as isoflavonoid O-glycosides, isoflavans, isoflav-2-enes, and others. The metabolite profiles of soy branches and pods have been less studied; however, approximately 20 flavonoids and isoflavonoids have been identified in each part. Other classes of compounds, such as steroids and steroid derivatives, coumarins and derivatives, and cinnamic acids and derivatives, have been found in underused soy parts.

Figure 4.

Classification of the metabolites identified in soy roots, leaves, branches, and pods according to ClassyFire.

Table 1 presents 38 isoflavonoids identified in one or more of the above-mentioned underused soy parts. Eight of them (daidzein, genistein, glycitein, daidzin, genistin, glycitin, malonyldaidzin, and malonylgenistin) were reported in all soy organs. Recent works showed promising biological activities of daidzein against colon cancer and hepatitis C virus [111,112]. Daidzin, which is a glyco-conjugate form of daidzein, presented therapeutic properties against multiple myeloma and epilepsy [113,114]. Bioactivity studies regarding the other aforementioned compounds also found properties against chronic vascular inflammation, human gastric cancer, breast cancer, and degenerative joint diseases [115,116,117]. Biochanin A, coumestrol, glyceollin, medicarpin, and ononin are more examples of widely known bioactive isoflavonoids which are found in different soy organs (see Table 1 for a summary) [118,119,120,121,122]. Carneiro et al. [38] quantified six isoflavones in soy branches, leaves, pods, and beans collected just after mechanical harvesting. Almost 3 kg of isoflavones were found per metric ton of soy leaves. However, less than 1 kg per metric ton was found in soy branches and pods. In soybeans, which are the main product of the soy plant, it was approximately 2 kg per metric ton.

Table 1.

Isoflavonoids identified in soy branches (B), leaves (L), pods (P), and roots (R).

| Name | Formula | B | L | P | R | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2′-hydroxydaidzein | C15H10O5 | X | [80] | |||

| 7,3′,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone | C15H10O5 | X | [79] | |||

| 7-O-methylluteone | C21H20O6 | X | [78] | |||

| acetyl daidzin | C22H22O9 | X | [104] | |||

| acetyl genistin | C23H22O11 | X | X | [94,104] | ||

| acetyl glycitin | C24H24O11 | X | [104] | |||

| afrormosin 7-O-glucoside | C23H24O10 | X | [80] | |||

| biochanin A | C16H12O5 | X | [80] | |||

| biochanin A 7-O-D-glucoside | C22H22O10 | X | [80] | |||

| biochanin A 7-O-glucoside-6′′-O-malonate | C25H24O13 | X | [80] | |||

| calycosin | C16H12O5 | X | [80] | |||

| coumestrol | C15H8O5 | X | X | [79,80,101] | ||

| daidzein | C15H10O4 | X | X | X | X | [38,78,79,80,94,98,101,103,104,106,107,108] |

| daidzin | C21H20O9 | X | X | X | X | [38,78,79,80,94,98,101,103,104,107,108] |

| formononetin | C16H12O4 | X | [80,102] | |||

| formononetin 7-O-glucoside | C22H22O9 | X | X | [79,80] | ||

| formononetin 7-O-glucoside-6′′-malonate | C25H24O12 | X | [78,80,94] | |||

| formononetin 7-O-glucoside-6-O-malonate | C25H24O12 | X | X | [78,79] | ||

| genistein | C15H10O5 | X | X | X | X | [38,79,94,98,104,108] |

| genistin | C21H20O10 | X | X | X | X | [38,78,79,94,101,104,107,108] |

| glyceollidin I/II | C20H20O5 | X | [80] | |||

| glyceollin I | C20H18O5 | X | [78,80] | |||

| glyceollin II | C20H18O5 | X | [78,80] | |||

| glyceollin III | C20H18O5 | X | [78,80] | |||

| glyceollin IV | C21H22O5 | X | [80] | |||

| glyceollin VI | C20H16O4 | X | [80] | |||

| glycitein | C16H12O5 | X | X | X | X | [38,80,98,104,108] |

| glycitein 7-O-glucoside | C22H22O10 | X | [80] | |||

| glycitin | C22H22O10 | X | X | X | X | [38,79,101,104,108] |

| isotrifoliol | C16H10O6 | X | [80] | |||

| malonyldaidzin | C24H22O12 | X | X | X | X | [38,78,79,80,94,101,103,104,107,108] |

| malonylgenistin | C24H22O13 | X | X | X | X | [78,79,80,94,101,104,107,108] |

| malonylglycitin | C25H24O13 | X | X | X | [80,94,104,108] | |

| medicarpin | C16H14O4 | X | [80] | |||

| neobavaisoflavone | C20H18O4 | X | X | [78,79] | ||

| phaseollin | C20H18O4 | X | [80] | |||

| pisatin | C17H14O6 | X | [80] | |||

| sojagol | C20H16O5 | X | [78,80] |

3.1. Roots

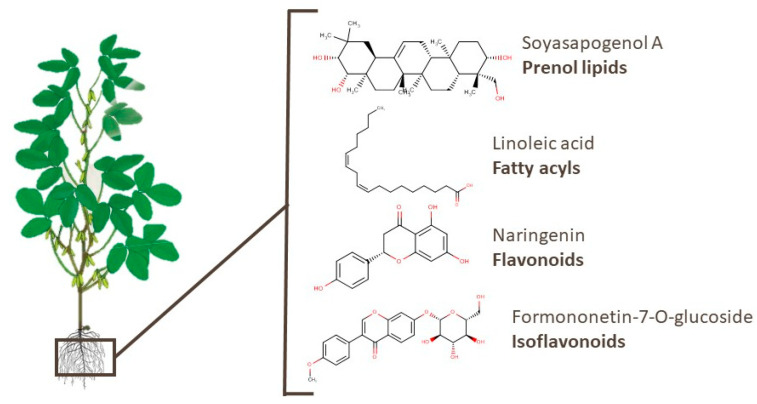

Different compounds belonging to the prenol lipids category, which are recognized by their bioactivity, have already been identified in soy. Table S1 contains 339 compounds found in soy roots, of which 33 are of this class [79,93,98,101,103,106,108]. Tsuno et al. [108] identified several soyasaponins, sapogenins, and isoflavones in soy root exudates. Soyasaponins have been linked to anti-obesity, anti-oxidative stress, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as preventive effects on hepatic triacylglycerol accumulation [123,124,125,126]. Omar et al. [127] identified the potent inhibitory effects of soyasapogenol A, which is a triterpenoid, against p53-deficient aggressive malignancies. In addition, other compounds of different classes, such as fatty acyls, isoflavonoids, flavonoids, and others, are presented in Table S1. Linoleic acid, naringenin, and formononetin-7-O-glucoside, which are examples of the aforementioned classes, have been related to cardiovascular health, neuroprotective effects, and anti-inflammatory properties [122,128,129]. The chemical structures of these bioactive compounds are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of soyasapogenol A, linoleic acid, naringenin, and formononetin-7-O-glucoside, which are examples of bioactive compounds identified in soy roots.

3.2. Leaves

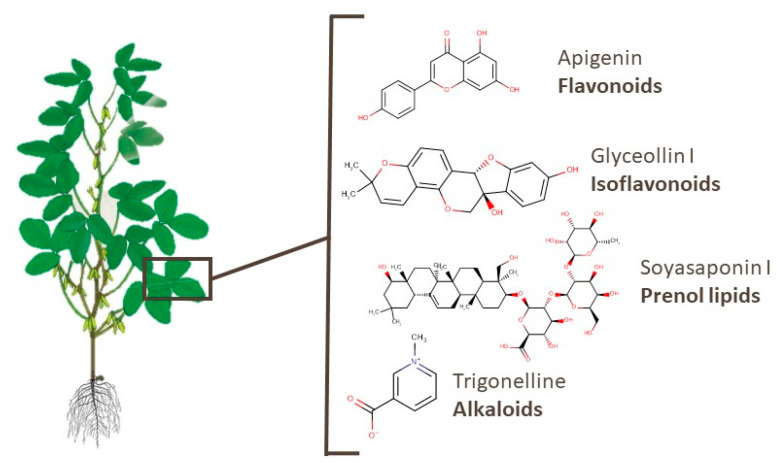

Leaves and roots are the most-studied underused soy parts. In Table S2, 259 metabolites of 32 classes identified in soy leaves are presented [38,78,80,94,98,101,102,103,106]. Almost 90 of these compounds are flavonoids, isoflavonoids, or prenol lipids. Widely known bioactive flavonoids such as apigenin, kaempferol, rutin, and others were also identified. Apigenin has been suggested as a potential anticancer agent [130]. Glyceollin I and soyasaponin I, an isoflavonoid and a prenol lipid, presented activities against breast cancer and Parkinson’s disease, respectively [120,131]. Moreover, different soyasaponins and even trigonelline, which is an alkaloid, were found in this part of the plant. For example, the latter substance was reported to have potential for lung cancer therapy, memory function recovery, and an anti-obesity effect [132,133,134]. Figure 6 shows the chemical structures of the aforementioned metabolites.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of apigenin, glyceollin I, soyasaponin I, and trigonelline, which are examples of bioactive compounds identified in soy leaves.

3.3. Branches

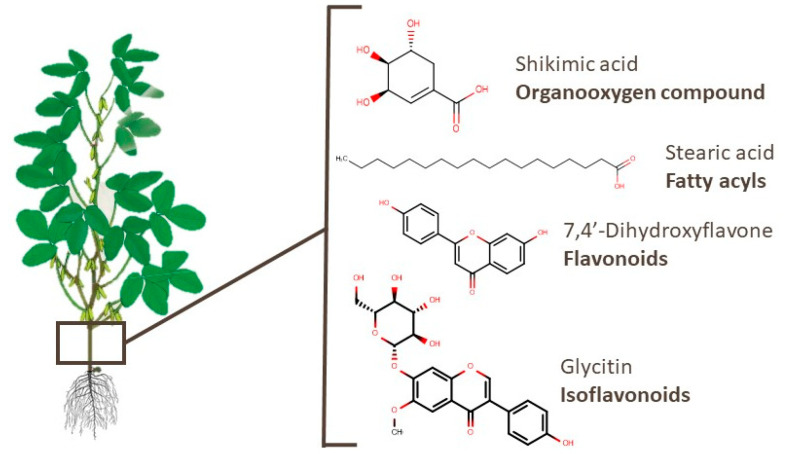

In soy branches, 197 compounds have already been identified, as presented in Table S3 [38,67,98,99,101]. The most widely reported class among these metabolites is the organooxygen compounds category (53 compounds), such as alcohols and polyols, carbohydrates and their conjugates, and carbonyl (Table S3). Shikimic acid, an example of an organooxygen compound, was linked to therapeutic effects in osteoarthritis [135]. Metabolites of other classes, such as succinic and stearic acids, presented an apoptotic effect in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and antifibrotic activity, respectively [136,137]. Flavonoids and isoflavonoids, such as 7,4′-dihydroxyflavone and glycitin, presented activity against lung diseases [138,139]. The chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of shikimic acid, stearic acid, 7,4′-dihydroxyflavone, and glycitin, which are examples of bioactive compounds identified in soy branches.

3.4. Pods

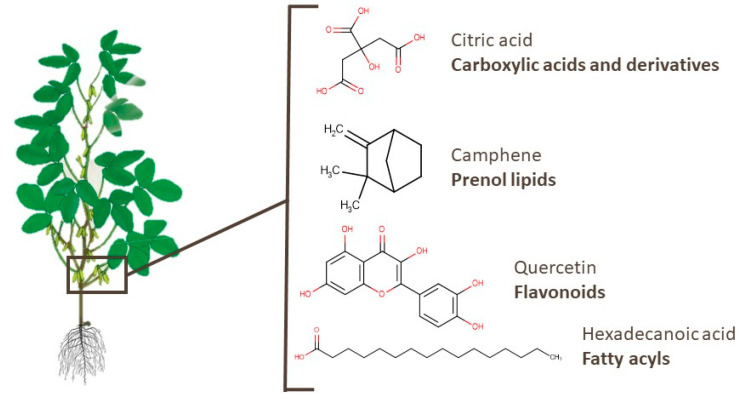

Similarly to branches, there are few metabolomics works identifying pod metabolites [38,98,100,104,105,107]. Amino acids, peptides, and mono-, di-, and tricarboxylic acids and their derivatives are the most mentioned types of compounds in pods, as shown in Table S4, with some of these substances already widely used in industry, such as citric and fumaric acids. Moreover, specialized metabolites such as camphene and α-pinene, which were also identified in soy pods, presented anti-skeletal muscle atrophy and neuroprotective effects, respectively [140,141]. Quercetin, which is a widely known flavonoid, may be a potential anti-inflammatory treatment in patients with COVID-19, as described by Saeedi-Boroujeni and Mahmoudian-Sani [142]. Hexadecanoic acid, a fatty acyl compound, presented an inhibitory effect on HT-29 human colon cancer cells [143]. Figure 8 presents the chemical structures of one compound of each class mentioned. In addition, fatty acyls, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, and other classes of compounds were identified in pods, leading to the 94 metabolites presented in Table S4.

Figure 8.

Chemical structures of citric acid, camphene, quercetin, and hexadecanoic acid, which are examples of bioactive compounds identified in soy pods.

4. Bioactive Compounds in Industrial By-Products from Soybean Processing—An Overview and Trends

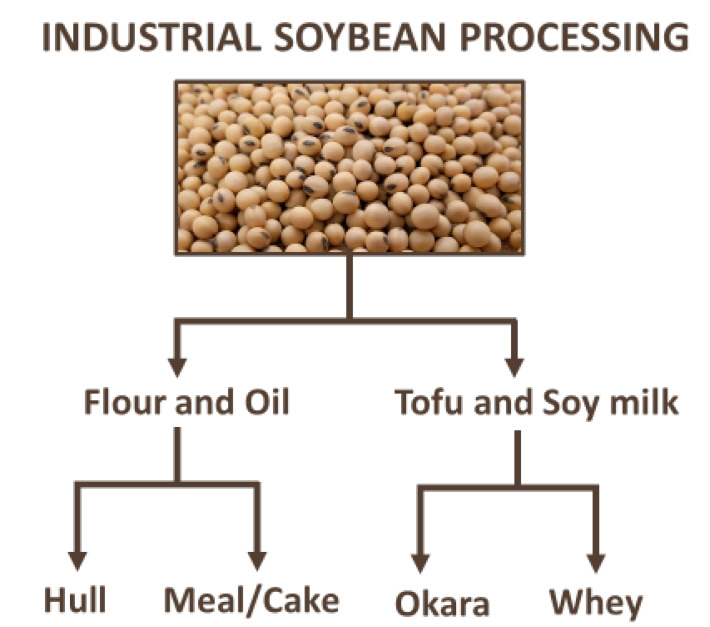

Underused soy parts are not the only by-products of soy. Soybean is transformed into different products, such as flour, oil, tofu, soy sauce, and soy milk, as presented in Figure 9. These processes generate by-products with vast applications, and their use as sources of bioactive compounds is an excellent opportunity to develop new ingredients and products with health benefits. In addition, green extractions of such materials provide more sustainable and valuable outcomes. Soy hull represents approximately 8% of the bean and is one of the by-products generated by soy flour and oil production [144]. Using a sustainable approach for valorizing soybean hull, Cabezudo et al. [145] optimized alkaline hydrolysis for polyphenol extraction and tested a fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae and α-amylase hydrolysis for the same purpose. In this work, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and isoflavones were identified by LC–MS, demonstrating the great potential of soy hull as a source of antioxidant compounds. Soybean meal is a by-product of soy oil production. The characterization of soybean meal demonstrated a higher antioxidant capacity and content of total phenolics, flavonoids, and saponins than in unprocessed grains [146]. In addition, different forms of isoflavones, such as β-glucosylated, malonyl glucosylated, acetyl glucosylated, and aglycones, as well as three group B soyasaponins were identified. Alvarez et al. [147] optimized a green supercritical fluid extraction using CO2 and ethanol to analyze soybean meal, resulting in extracts with antioxidant properties and a higher content of phenols and flavonoids. Freitas et al. [148] also used green extraction to obtain an aqueous extract of soy meal with a high inhibition of lipid peroxidation, identifying 16 phenolics in the extract. Okara and soy whey, which are by-products of soymilk and tofu production, have also been used as a source of bioactive compounds. Nkurunziza et al. [149] extracted different isoflavone aglycones of okara using subcritical water. In addition, Nile et al. [150] found a high level of isoflavones in okara, as well as potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and inhibitory enzyme activities. Liu et al. [151] used foam fractionation and acidic hydrolysis to remove proteins from soy whey, generating extracts with a high level of isoflavone aglycones. Other uses for and information about soy whey are described by Chua and Liu [152] and Davy and Vuong [153].

Figure 9.

Industrial soybean processing and its respective products and by-products.

Additionally, biotechnology advances produce new opportunities to develop fermented soy products with more health benefits [154,155,156,157]. Furthermore, metabolomics contributes to a better understanding of the biotransformation of bioactive compounds [158]. As a substrate for microorganisms, okara has been widely used in different fermented modes [159,160,161,162,163,164]. Rhizopus oligosporus, Bacillus subtilis WX-17, and Eurotium cristatum were used for okara fermentation, resulting in products with higher bioactivity, nutritional composition, and anti-diabetic potential [159,160,161,162,163,164]. In addition, higher levels of phenolics, flavonoids, and biotransformed substances were identified. The fermentation of other soy by-products, such as meal, whey, and hull, has demonstrated vast potential for enhancing the bioactivity of the final products [165,166,167,168,169,170,171].

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Soy is the major oilseed crop worldwide, and its large production generates a massive amount of by-products. The presence of isoflavonoids, flavonoids, terpenes, and other substances in soy branches or stems, leaves, pods, and roots, provides insights into the use of these underused materials as a source of bioactive compounds. In contrast, challenges for the valorization of such by-products remain. A multi-omics approach, as proposed by foodomics, may reduce the gap between the crude parts of soy and the final ingredient or product, increasing the safety and quality of all the processes and products involved. Moreover, soy metabolomics studies have focused on specific organs as well as metabolic modifications, resulting in an incomplete metabolite profile of all soy parts. In summary, our review demonstrates the extensive use of metabolomics in soy research and how this work provides new information for alternative uses of underused soy parts with more added value. Interestingly, our work also shows that there are many (underused) soy compounds that still need to be interrogated for their potential bioactivity and possible health benefits.

In addition, more studies about the life-cycle assessment (LCA) of the soybean supply chain are required to analyze potential problems related to the high amount of by-products which are left on the ground post-harvest. Environmental problems such as soil and water contamination could occur due to the presence of several bioactive compounds present in such agricultural by-products. The use of green extraction and biotechnology could be feasible alternatives for the re-use of these materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pixabay (https://www.pixabay.com—accessed on 20 March 2021) for the free images, and Gari Vidal Ccana Ccapatinta for help with JChem.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods10061308/s1: Table S1. Metabolites identified in soy roots, Table S2. Metabolites identified in soy leaves, Table S3. Metabolites identified in soy branches, and Table S4. Metabolites identified in soy pods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.B., C.S.F., E.I., A.C.; data curation, F.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.B.; writing—review and editing, C.S.F., E.I., A.C.; supervision, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP, grant number 2020/09500-0, 2018/21128-9 and 2017/06216-6, and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Atanasov A.G., the International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce. Zotchev S.B., Dirsch V.M., Supuran C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021;20:200–216. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemat F., Vian M.A., Fabiano-Tixier A.-S., Nutrizio M., Jambrak A.R., Munekata P.E.S., Lorenzo J.M., Barba F.J., Binello A., Cravotto G. A review of sustainable and intensified techniques for extraction of food and natural products. Green Chem. 2020;22:2325–2353. doi: 10.1039/C9GC03878G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armenta S., Garrigues S., Esteve-Turrillas F.A., de la Guardia M. Green extraction techniques in green analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;116:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Rivera G., Bueno M., Ballesteros-Vivas D., Mendiola J.A., Ibañez E. Pressurized liquid extraction. In: Poole C.F., editor. Liquid-Phase Extraction. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. pp. 375–398. Handbooks in Separation Science. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai Y., Yusup S., Kadir W., Wong C., Rosli S., Ruslan M., Chin B., Yiin C. Valorization of Tropical Biomass Waste by Supercritical Fluid Extraction Technology. Sustainability. 2020;13:233. doi: 10.3390/su13010233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sánchez-Camargo A.D.P., Parada-Alonso F., Ibáñez E., Cifuentes A. Recent applications of on-line supercritical fluid extraction coupled to advanced analytical techniques for compounds extraction and identification. J. Sep. Sci. 2019;42:243–257. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201800729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keppler E.A.H., Jenkins C., Davis T.J., Bean H.D. Advances in the application of comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography in metabolomics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;109:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirok B.W.J., Stoll D.R., Schoenmakers P.J. Recent Developments in Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography: Fundamental Improvements for Practical Applications. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:240–263. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez G., Montero L., Llorens L., Castro-Puyana M., Cifuentes A. Recent advances in the application of capillary electromigration methods for food analysis and Foodomics. Electrophoresis. 2018;39:136–159. doi: 10.1002/elps.201700321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez-Rivera G., Ballesteros-Vivas D., Parada-Alfonso F., Ibañez E., Cifuentes A. Recent applications of high resolution mass spectrometry for the characterization of plant natural products. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;112:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aksenov A.A., Da Silva R., Knight R., Lopes N.P., Dorrestein P.C. Global chemical analysis of biology by mass spectrometry. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:0054. doi: 10.1038/s41570-017-0054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAlpine J.B., Chen S.-N., Kutateladze A., MacMillan J.B., Appendino G., Barison A., Beniddir M.A., Biavatti M.W., Bluml S., Boufridi A., et al. The value of universally available raw NMR data for transparency, reproducibility, and integrity in natural product research. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019;36:35–107. doi: 10.1039/C7NP00064B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorokina M., Steinbeck C. Review on natural products databases: Where to find data in 2020. J. Chemin. 2020;12:1–51. doi: 10.1186/s13321-020-00424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medema M.H. The year 2020 in natural product bioinformatics: An overview of the latest tools and databases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021;38:301–306. doi: 10.1039/D0NP00090F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nothias L.-F., Petras D., Schmid R., Dührkop K., Rainer J., Sarvepalli A., Protsyuk I., Ernst M., Tsugawa H., Fleischauer M., et al. Feature-based molecular networking in the GNPS analysis environment. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:905–908. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0933-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reher R., Kim H.W., Zhang C., Mao H.H., Wang M., Nothias L.-F., Caraballo-Rodriguez A.M., Glukhov E., Teke B., Leao T., et al. A Convolutional Neural Network-Based Approach for the Rapid Annotation of Molecularly Diverse Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:4114–4120. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAOSTAT. [(accessed on 2 February 2021)]; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

- 18.Ishangulyyev R., Kim S., Lee S.H. Understanding Food Loss and Waste—Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food? Foods. 2019;8:297. doi: 10.3390/foods8080297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali S.S., Bharadwaj S. Prospects for Detecting the 326.5 MHz Redshifted 21-Cm HI Signal with the Ooty Radio Telescope (ORT) Volume 35. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome, Italy: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.UN DP Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. United Nations Development Programme; New York, NY, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cifuentes A. Food analysis and Foodomics. J. Chromatogr. A. 2009;1216:7109. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valdés A., Cifuentes A., León C. Foodomics evaluation of bioactive compounds in foods. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017;96:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsinas N., da Silva A.B., Enríquez-De-Salamanca A., Fernández N., Bronze M.R., Rodríguez-Rojo S. Pressurized Liquid Extraction Optimization from Supercritical Defatted Olive Pomace: A Green and Selective Phenolic Extraction Process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:5590–5602. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c09426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assirati J., Rinaldo D., Rabelo S.C., Bolzani V.D.S., Hilder E.F., Funari C.S. A green, simplified, and efficient experimental setup for a high-throughput screening of agri-food by-products—From polar to nonpolar metabolites in sugarcane solid residues. J. Chromatogr. A. 2020;1634:461693. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sánchez-Martínez J.D., Bueno M., Alvarez-Rivera G., Tudela J., Ibañez E., Cifuentes A. In vitro neuroprotective potential of terpenes from industrial orange juice by-products. Food Funct. 2021;12:302–314. doi: 10.1039/D0FO02809F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal M., Ajazuddin, Tripathi D.K., Saraf S., Saraf S., Antimisiaris S.G., Mourtas S., Hammarlund-Udenaes M., Alexander A. Recent advancements in liposomes targeting strategies to cross blood-brain barrier (BBB) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Control. Release. 2017;260:61–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson E.J., Ali M.L., Beavis W.D., Chen P., Clemente T.E., Diers B.W., Graef G.L., Grassini P., Hyten D.L., McHale L.K., et al. Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] Breeding: History, Improvement, Production and Future Opportunities. In: Al-Khayri J.M., Jain S.M., Johnson D.V., editors. Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Legumes. Volume 7. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2019. pp. 431–516. [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations United Nations Statistics Division-Environment Statistics. [(accessed on 20 March 2021)]; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/environment/totalarea.htm.

- 29.United States Department of Agriculture Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. [(accessed on 20 March 2021)];2021 Available online: https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/tx31qh68h/hq37wg66q/q237jm44p/oilseeds.pdf.

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. [(accessed on 20 March 2021)];2011 Available online: https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/tx31qh68h/w3763722n/db78tc388/oilseed-trade-03-10-2011.pdf.

- 31.Krisnawati A., Adie M.M. Variability of Biomass and Harvest Index from Several Soybean Genotypes as Renewable Energy Source. Energy Procedia. 2015;65:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buffett H.G. Conservation: Reaping the Benefits of No-Tillage Farming. Nature. 2012;484:455. doi: 10.1038/484455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gawęda D., Haliniarz M., Bronowicka-Mielniczuk U., Łukasz J. Weed Infestation and Health of the Soybean Crop Depending on Cropping System and Tillage System. Agriculture. 2020;10:208. doi: 10.3390/agriculture10060208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Castro S.G.Q., Dinardo-Miranda L.L., Fracasso J.V., Bordonal R.O., Menandro L., Franco H.C.J., Carvalho J.L.N. Changes in Soil Pest Populations Caused by Sugarcane Straw Removal in Brazil. BioEnergy Res. 2019;12:878–887. doi: 10.1007/s12155-019-10019-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J., Hang X., Lamine S.M., Jiang Y., Afreh D., Qian H., Feng X., Zheng C., Deng A., Song Z., et al. Interactive effects of straw incorporation and tillage on crop yield and greenhouse gas emissions in double rice cropping system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017;250:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2017.07.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popin G.V., Santos A.K.B., Oliveira T.D.P., De Camargo P.B., Cerri C.E., Siqueira-Neto M. Sugarcane straw management for bioenergy: Effects of global warming on greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon storage. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2020;25:559–577. doi: 10.1007/s11027-019-09880-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasconcelos A.L.S., Cherubin M.R., Feigl B.J., Cerri C.E., Gmach M.R., Siqueira-Neto M. Greenhouse gas emission responses to sugarcane straw removal. Biomass Bioenergy. 2018;113:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2018.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carneiro A.M., Moreira E.A., Bragagnolo F.S., Borges M.S., Pilon A.C., Rinaldo D., De Funari C.S. Soya agricultural waste as a rich source of isoflavones. Food Res. Int. 2020;130:108949. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatterjee C., Gleddie S., Xiao C.-W. Soybean Bioactive Peptides and Their Functional Properties. Nutrients. 2018;10:1211. doi: 10.3390/nu10091211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y.-M., Yoon Y., Yoon H., Park H.-M., Song S., Yeum K.-J. Dietary Anthocyanins against Obesity and Inflammation. Nutrients. 2017;9:1089. doi: 10.3390/nu9101089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Křížová L., Dadáková K., Kašparovská J., Kašparovský T. Isoflavones. Molecules. 2019;24:1076. doi: 10.3390/molecules24061076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Messina M. Soy and Health Update: Evaluation of the Clinical and Epidemiologic Literature. Nutrients. 2016;8:754. doi: 10.3390/nu8120754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landete J.M., Arques J.L., Medina M., Gaya P., Rivas B.D.L., Muñoz R. Bioactivation of Phytoestrogens: Intestinal Bacteria and Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;56:1826–1843. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.789823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamagata K. Soy Isoflavones Inhibit Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Prevent Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2019;74:201–209. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pabich M., Materska M. Biological Effect of Soy Isoflavones in the Prevention of Civilization Diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11:1660. doi: 10.3390/nu11071660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thangavel P., Puga-Olguín A., Rodríguez-Landa J.F., Zepeda R.C. Genistein as Potential Therapeutic Candidate for Menopausal Symptoms and Other Related Diseases. Molecules. 2019;24:3892. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taku K., Melby M.K., Nishi N., Omori T., Kurzer M.S. Soy isoflavones for osteoporosis: An evidence-based approach. Maturitas. 2011;70:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreira E.A., Pilon A.C., Andrade L.E., Lopes N.P. New Perspectives on Chlorogenic Acid Accumulation in Harvested Leaf Tissue: Impact on Traditional Medicine Preparations. ACS Omega. 2018;3:18380–18386. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neilson E.H., Goodger J.Q., Woodrow I.E., Møller B.L. Plant chemical defense: At what cost? Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gottlieb O.R. Phytochemicals: Differentiation and function. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:1715–1724. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85002-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu Y., Lam H.-M., Pi E., Zhan Q., Tsai S., Wang C., Kwan Y., Ngai S. Comparative Metabolomics in Glycine Max and Glycine soja under Salt Stress To Reveal the Phenotypes of Their Offspring. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:8711–8721. doi: 10.1021/jf402043m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yun D.-Y., Kang Y.-G., Yun B., Kim E.-H., Kim M., Park J.S., Lee J.H., Hong Y.-S. Distinctive Metabolism of Flavonoid between Cultivated and Semiwild Soybean Unveiled through Metabolomics Approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:5773–5783. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patent Database Search Results: TTL/“Soybean Cultivar” OR TTL/“Soybean Variety” in US Patent Collection. [(accessed on 10 May 2021)]; Available online: http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&p=1&u=%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-bool.html&r=0&f=S&l=50&TERM1=%22soybean+cultivar%22&FIELD1=TI&co1=OR&TERM2=%22soybean+variety%22&FIELD2=TI&d=PTXT.

- 54.Lee J., Hwang Y.-S., Kim S.T., Yoon W.-B., Han W.Y., Kang I.-K., Choung M.-G. Seed coat color and seed weight contribute differential responses of targeted metabolites in soybean seeds. Food Chem. 2017;214:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta R., Min C.W., Kim S.W., Wang Y., Agrawal G.K., Rakwal R., Kim S.G., Lee B.W., Ko J.M., Baek I.Y., et al. Comparative investigation of seed coats of brown- versus yellow-colored soybean seeds using an integrated proteomics and metabolomics approach. Proteomics. 2015;15:1706–1716. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang C.-Q., Zheng L., Wu H.-J., Zhu Z.-K., Zou Y.-F., Deng J.-C., Qin W.-T., Zhang J., Wang X.-C., Yang W.-Y., et al. Yellow- and green-cotyledon seeds of black soybean: Phytochemical and bioactive differences determine edibility and medical applications. Food Biosci. 2021;39:100842. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yun Y.J., Lee H., Yoo D.J., Yang J.Y., Woo S.-Y., Seo W.D., Kim Y.-C., Lee J.H. Molecular analysis of soyasaponin biosynthetic genes in two soybean (Glycine Max L. Merr.) cultivars. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2021;15:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s11816-021-00661-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García-Villalba R., León C., Dinelli G., Carretero A.S., Fernández-Gutiérrez A., Garcia-Cañas V., Cifuentes A. Comparative metabolomic study of transgenic versus conventional soybean using capillary electrophoresis–time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1195:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harrigan G.G., Skogerson K., MacIsaac S., Bickel A., Perez T., Li X. Application of 1H NMR Profiling To Assess Seed Metabolomic Diversity. A Case Study on a Soybean Era Population. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63:4690–4697. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarke J.D., Alexander D.C., Ward D.P., Ryals J.A., Mitchell M.W., Wulff J.E., Guo L. Assessment of Genetically Modified Soybean in Relation to Natural Variation in the Soybean Seed Metabolome. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3082. doi: 10.1038/srep03082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Campos B.K., Galazzi R.M., dos Santos B.M., Balbuena T.S., dos Santos F.N., Mokochinski J.B., Eberlin M.N., Arruda M.A. Comparison of generational effect on proteins and metabolites in non-transgenic and transgenic soybean seeds through the insertion of the cp4-EPSPS gene assessed by omics-based platforms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;202:110918. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodrigues J.M., Coutinho F.S., dos Santos D.S., Vital C.E., Ramos J.R.L.S., Reis P.B., Oliveira M.G.A., Mehta A., Fontes E.P.B., Ramos H.J.O. BiP-overexpressing soybean plants display accelerated hypersensitivity response (HR) affecting the SA-dependent sphingolipid and flavonoid pathways. Phytochemistry. 2021;185:112704. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang W.-S., Chen L.-J., Wang Y.-Y., Zhu X.-F., Liu X.-Y., Fan H.-Y., Duan Y.-X. Bacillus simplex treatment promotes soybean defence against soybean cyst nematodes: A metabolomics study using GC-MS. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakata R., Yano M., Hiraga S., Teraishi M., Okumoto Y., Mori N., Kaga A. Molecular Basis Underlying Common Cutworm Resistance of the Primitive Soybean Landrace Peking. Front. Genet. 2020;11:11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.581917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang P., Du H., Wang J., Pu Y., Yang C., Yan R., Yang H., Cheng H., Yu D. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-mediated metabolic engineering increases soya bean isoflavone content and resistance to soya bean mosaic virus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;18:1384–1395. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding X., Wang X., Li Q., Yu L., Song Q., Gai J., Yang S. Metabolomics Studies on Cytoplasmic Male Sterility during Flower Bud Development in Soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2869. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ranjan A., Westrick N.M., Jain S., Piotrowski J.S., Ranjan M., Kessens R., Stiegman L., Grau C.R., Conley S., Smith D.L., et al. Resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean involves a reprogramming of the phenylpropanoid pathway and up-regulation of antifungal activity targeting ergosterol biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:1567–1581. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Oliveira C.S., Lião L.M., Alcantara G.B. Metabolic response of soybean plants to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection. Phytochemistry. 2019;167:112099. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui J.-Q., Sun H.-B., Sun M.-B., Liang R.-T., Jie W.-G., Cai B.-Y. Effects of Funneliformis mosseae on Root Metabolites and Rhizosphere Soil Properties to Continuously-Cropped Soybean in the Potted-Experiments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2160. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu L., Zhou Y., Li X., Zhao J., Guo N., Xing H. Metabolomics Analysis of Soybean Hypocotyls in Response to Phytophthora sojae Infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1530. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang W., Zhu X., Wang Y., Chen L., Duan Y. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal that bacteria promote plant defense during infection of soybean cyst nematode in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1302-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Copley T.R., Aliferis K.A., Kliebenstein D.J., Jabaji S.H. An integrated RNAseq-1H NMR metabolomics approach to understand soybean primary metabolism regulation in response to Rhizoctonia foliar blight disease. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lardi M., Murset V., Fischer H.-M., Mesa S., Ahrens C.H., Zamboni N., Pessi G. Metabolomic Profiling of Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens-Induced Root Nodules Reveals Both Host Plant-Specific and Developmental Signatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:815. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abeysekara N.S., Swaminathan S., Desai N., Guo L., Bhattacharyya M.K. The plant immunity inducer pipecolic acid accumulates in the xylem sap and leaves of soybean seedlings following Fusarium virguliforme infection. Plant Sci. 2016;243:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scandiani M.M., Luque A.G., Razori M.V., Casalini L.C., Aoki T., O’Donnell K., Cervigni G.D.L., Spampinato C.P. Metabolic profiles of soybean roots during early stages of Fusarium tucumaniae infection. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;66:391–402. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sato D., Akashi H., Sugimoto M., Tomita M., Soga T. Metabolomic profiling of the response of susceptible and resistant soybean strains to foxglove aphid, Aulacorthum solani Kaltenbach. J. Chromatogr. B. 2013;925:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brechenmacher L., Lei Z., Libault M., Findley S., Sugawara M., Sadowsky M.J., Sumner L.W., Stacey G. Soybean Metabolites Regulated in Root Hairs in Response to the Symbiotic Bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1808–1822. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Silva E., Perez Da Graça J., Porto C., Martin Do Prado R., Nunes E., Corrêa Marcelino-Guimarães F., Conrado Meyer M., Jorge Pilau E. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis by UHPLC-MS/MS of Soybean Plant in a Compatible Response to Phakopsora Pachyrhizi Infection. Metabolites. 2021;11:179. doi: 10.3390/metabo11030179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zanzarin D.M., Hernandes C.P., Leme L.M., Silva E., Porto C., Prado R.M.D., Meyer M.C., Favoreto L., Nunes E., Pilau E.J. Metabolomics of soybean green stem and foliar retention (GSFR) disease using mass spectrometry and molecular networking. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019;34:e8655. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silva E., Da Graça J.P., Porto C., Prado R.M.D., Hoffmann-Campo C.B., Meyer M.C., Nunes E., Pilau E.J. Unraveling Asian Soybean Rust metabolomics using mass spectrometry and Molecular Networking approach. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:138. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56782-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee J., Hwang Y.S., Chang W.S., Moon J.K., Choung M.G. Seed Maturity Differentially Mediates Metabolic Responses in Black Soybean. Food Chem. 2013;141:2052–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Collakova E., Aghamirzaie D., Fang Y., Klumas C., Tabataba F., Kakumanu A., Myers E., Heath L.S., Grene R. Metabolic and Transcriptional Reprogramming in Developing Soybean (Glycine Max) Embryos. Metabolites. 2013;3:347–372. doi: 10.3390/metabo3020347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li L., Hur M., Lee J.Y., Zhou W., Song Z., Ransom N., Demirkale C.Y., Nettleton D., Westgate M., Arendsee Z., et al. A Systems Biology Approach toward Understanding Seed Composition in Soybean. BMC Genom. 2015;16:S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S3-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gu E.J., Kim D.W., Jang G.J., Song S.H., Lee J.I., Lee S.B., Kim B.M., Cho Y., Lee H.J., Kim H.J. Mass-Based Metabolomic Analysis of Soybean Sprouts during Germination. Food Chem. 2017;217:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Song H.H., Ryu H.W., Lee K.J., Jeong I.Y., Kim D.S., Oh S.R. Metabolomics Investigation of Flavonoid Synthesis in Soybean Leaves Depending on the Growth Stage. Metabolomics. 2014;10:833–841. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0640-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Makino Y., Nishizaka A., Yoshimura M., Sotome I., Kawai K., Akihiro T. Influence of Low O2 and High CO2 Environment on Changes in Metabolite Concentrations in Harvested Vegetable Soybeans. Food Chem. 2020;317:126380. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pi E., Zhu C., Fan W., Huang Y., Qu L., Li Y., Zhao Q., Ding F., Qiu L., Wang H., et al. Quantitative Phosphoproteomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal GmMYB173 Optimizes Flavonoid Metabolism in Soybean under Salt Stress. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2018;17:1209–1224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Das A., Rushton P.J., Rohila J.S. Metabolomic Profiling of Soybeans (Glycine Max L.) Reveals the Importance of Sugar and Nitrogen Metabolism under Drought and Heat Stress. Plants. 2017;6:21. doi: 10.3390/plants6020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zou J., Yu H., Yu Q., Jin X., Cao L., Wang M., Wang M., Ren C., Zhang Y. Physiological and UPLC-MS/MS Widely Targeted Metabolites Mechanisms of Alleviation of Drought Stress-Induced Soybean Growth Inhibition by Melatonin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021;163:113323. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gupta R., Min C.W., Kramer K., Agrawal G.K., Rakwal R., Park K.H., Wang Y., Finkemeier I., Kim S.T. A Multi-Omics Analysis of Glycine Max Leaves Reveals Alteration in Flavonoid and Isoflavonoid Metabolism Upon Ethylene and Abscisic Acid Treatment. Proteomics. 2018;18:1700366. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201700366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cheng J., Yuan C., Graham T.L. Potential Defense-Related Prenylated Isoflavones in Lactofen-Induced Soybean. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li Y., Zhang Q., Yu Y., Li X., Tan H. Integrated proteomics, metabolomics and physiological analyses for dissecting the toxic effects of halosulfuron-methyl on soybean seedlings (Glycine Max merr.) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020;157:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhong Z., Kobayashi T., Zhu W., Imai H., Zhao R., Ohno T., Rehman S.U., Uemura M., Tian J., Komatsu S. Plant-derived smoke enhances plant growth through ornithine-synthesis pathway and ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in soybean. J. Proteom. 2020;221:103781. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ban Y.J., Song Y.H., Kim J.Y., Baiseitova A., Lee K.W., Kim K.D., Park K.H. Comparative investigation on metabolites changes in soybean leaves by ethylene and activation of collagen synthesis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020;154:112743. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yilmaz A., Rudolph H.L., Hurst J.J., Wood T.D. High-Throughput Metabolic Profiling of Soybean Leaves by Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2015;88:1188–1194. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yun D.-Y., Kang Y.-G., Kim E.-H., Kim M., Park N.-H., Choi H.-T., Go G.H., Lee J.H., Park J.S., Hong Y.-S. Metabolomics approach for understanding geographical dependence of soybean leaf metabolome. Food Res. Int. 2018;106:842–852. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Feng Z., Ding C., Li W., Wang D., Cui D. Applications of metabolomics in the research of soybean plant under abiotic stress. Food Chem. 2020;310:125914. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seo W.D., Kang J.E., Choi S.-W., Lee K.-S., Lee M.-J., Park K.-D., Lee J.H. Comparison of nutritional components (isoflavone, protein, oil, and fatty acid) and antioxidant properties at the growth stage of different parts of soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merrill] Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017;26:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jiang Z.-F., Liu D.-D., Wang T.-Q., Liang X.-L., Cui Y.-H., Liu Z.-H., Li W.-B. Concentration difference of auxin involved in stem development in soybean. J. Integr. Agric. 2020;19:953–964. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62676-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hu B.-Y., Yang C.-Q., Iqbal N., Deng J.-C., Zhang J., Yang W.-Y., Liu J. Development and validation of a GC–MS method for soybean organ-specific metabolomics. Plant Prod. Sci. 2018;21:215–224. doi: 10.1080/1343943X.2018.1488539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dresler S., Wójciak-Kosior M., Sowa I., Strzemski M., Sawicki J., Kováčik J., Blicharski T. Effect of Long-Term Strontium Exposure on the Content of Phytoestrogens and Allantoin in Soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3864. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nam K.-H., Kim D.Y., Kim H.J., Pack I.-S., Chung Y.S., Kim S.Y., Kim C.-G. Global metabolite profiling based on GC–MS and LC–MS/MS analyses in ABF3-overexpressing soybean with enhanced drought tolerance. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2019;62:15. doi: 10.1186/s13765-019-0425-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Coutinho I.D., Henning L.M.M., Döpp S.A., Nepomuceno A., Moraes L.A.C., Marcolino-Gomes J., Richter C., Schwalbe H., Colnago L.A. Identification of primary and secondary metabolites and transcriptome profile of soybean tissues during different stages of hypoxia. Data Brief. 2018;21:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.09.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Silva F.A.C., Carrão-Panizzi M.C., Blassioli-Moraes M.C., Panizzi A.R. Influence of Volatile and Nonvolatile Secondary Metabolites From Soybean Pods on Feeding and on Oviposition Behavior of Euschistus heros (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) Environ. Entomol. 2013;42:1375–1382. doi: 10.1603/EN13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deng J.-C., Yang C.-Q., Zhang J., Zhang Q., Yang F., Yang W.-Y., Liu J. Organ-Specific Differential NMR-Based Metabonomic Analysis of Soybean [Glycine Max (L.) Merr.] Fruit Reveals the Metabolic Shifts and Potential Protection Mechanisms Involved in Field Mold Infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li M., Xu J., Wang X., Fu H., Zhao M., Wang H., Shi L. Photosynthetic characteristics and metabolic analyses of two soybean genotypes revealed adaptive strategies to low-nitrogen stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2018;229:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dillon F.M., Chludil H.D., Mithöfer A., Zavala J.A. Solar UVB-inducible ethylene alone induced isoflavonoids in pods of field-grown soybean, an important defense against stink bugs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020;178:104167. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tsuno Y., Fujimatsu T., Endo K., Sugiyama A., Yazaki K. Soyasaponins: A New Class of Root Exudates in Soybean (Glycine Max) Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:366–375. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.ChemAxon-Software Solutions and Services for Chemistry & Biology. [(accessed on 8 April 2021)]; Available online: https://chemaxon.com/products/marvin.

- 110.Djoumbou Feunang Y., Eisner R., Knox C., Chepelev L., Hastings J., Owen G., Fahy E., Steinbeck C., Subramanian S., Bolton E., et al. ClassyFire: Automated Chemical Classification with a Comprehensive, Computable Taxonomy. J. Chemin. 2016;8:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13321-016-0174-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Salama A.A.A., Allam R.M. Promising Targets of Chrysin and Daidzein in Colorectal Cancer: Amphiregulin, CXCL1, and MMP-9. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021;892:173763. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.He Y., Huang M., Tang C., Yue Y., Liu X., Zheng Z., Dong H., Liu D. Dietary Daidzein Inhibits Hepatitis C Virus Replication by Decreasing MicroRNA-122 Levels. Virus Res. 2021;298:198404. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2021.198404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang M.H., Jung S.H., Chinnathambi A., Alahmadi T.A., Alharbi S.A., Sethi G., Ahn K.S. Attenuation of STAT3 Signaling Cascade by Daidzin Can Enhance the Apoptotic Potential of Bortezomib against Multiple Myeloma. Biomolecules. 2020;10:23. doi: 10.3390/biom10010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kazmi Z., Zeeshan S., Khan A., Malik S., Shehzad A., Seo E.K., Khan S. Anti-Epileptic Activity of Daidzin in PTZ-Induced Mice Model by Targeting Oxidative Stress and BDNF/VEGF Signaling. NeuroToxicology. 2020;79:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xie X., Cong L., Liu S., Xiang L., Fu X. Genistein Alleviates Chronic Vascular Inflammatory Response via the MiR-21/NF-ΚB P65 Axis in Lipopolysaccharide-Treated Mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021;23:192. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.11831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zang Y.Q., Feng Y.Y., Luo Y.H., Zhai Y.Q., Ju X.Y., Feng Y.C., Wang J.R., Yu C.Q., Jin C.H. Glycitein Induces Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Apoptosis and G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest through the MAPK/STAT3/NF-ΚB Pathway in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Drug Dev. Res. 2019;80:573–584. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hwang S.T., Yang M.H., Baek S.H., Um J.Y., Ahn K.S. Genistin Attenuates Cellular Growth and Promotes Apoptotic Cell Death Breast Cancer Cells through Modulation of ERalpha Signaling Pathway. Life Sci. 2020;263:118594. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou Y., Xu B., Yu H., Zhao W., Song X., Liu Y., Wang K., Peacher N., Zhao X., Zhang H.T. Biochanin A Attenuates Ovariectomy-Induced Cognition Deficit via Antioxidant Effects in Female Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:171. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.603316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Xu Y., Zhang Y., Liang H., Liu X. Coumestrol Mitigates Retinal Cell Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Diabetic Retinopathy via Activation of SIRT1. Aging. 2021;13:5342–5357. doi: 10.18632/aging.202467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yamamoto T., Sakamoto C., Tachiwana H., Kumabe M., Matsui T., Yamashita T., Shinagawa M., Ochiai K., Saitoh N., Nakao M. Endocrine Therapy-Resistant Breast Cancer Model Cells Are Inhibited by Soybean Glyceollin I through Eleanor Non-Coding RNA. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mansoori M.N., Raghuvanshi A., Shukla P., Awasthi P., Trivedi R., Goel A., Singh D. Medicarpin Prevents Arthritis in Post-Menopausal Conditions by Arresting the Expansion of TH17 Cells and pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;82:106299. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Luo L., Zhou J., Zhao H., Fan M., Gao W. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Formononetin and Ononin on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Zebrafish Models Based on Lipidomics and Targeted Transcriptomics. Metabolomics. 2019;15:153. doi: 10.1007/s11306-019-1614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tsai W., Nakamura Y., Akasaka T., Katakura Y., Tanaka Y., Shirouchi B., Jiang Z., Yuan X., Sato M. Soyasaponin Ameliorates Obesity and Reduces Hepatic Triacylglycerol Accumulation by Suppressing Lipogenesis in High-fat Diet-fed Mice. J. Food Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim H.J., Choi E.J., Kim H.S., Choi C.W., Choi S.W., Kim S.L., Seo W.D., Do S.H. Soyasaponin Ab Alleviates Postmenopausal Obesity through Browning of White Adipose Tissue. J. Funct. Foods. 2019;57:453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu X., Chen K., Zhu L., Liu H., Ma T., Xu Q., Xie T. Soyasaponin Ab Protects against Oxidative Stress in HepG2 Cells via Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Signaling Pathways. J. Funct. Foods. 2018;45:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang F., Gong S., Wang T., Li L., Luo H., Wang J., Huang C., Zhou H., Chen G., Liu Z., et al. Soyasaponin II Protects against Acute Liver Failure through Diminishing YB-1 Phosphorylation and Nlrp3-Inflammasome Priming in Mice. Theranostics. 2020;10:2714–2726. doi: 10.7150/thno.40128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Omar A., Kalra R.S., Putri J., Elwakeel A., Kaul S.C., Wadhwa R. Soyasapogenol-A Targets CARF and Results in Suppression of Tumor Growth and Metastasis in P53 Compromised Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jandacek R.J. Linoleic Acid: A Nutritional Quandary. Healthcare. 2017;5:25. doi: 10.3390/healthcare5020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nouri Z., Fakhri S., El-Senduny F.F., Sanadgol N., Abd-Elghani G.E., Farzaei M.H., Chen J.T. On the Neuroprotective Effects of Naringenin: Pharmacological Targets, Signaling Pathways, Molecular Mechanisms, and Clinical Perspective. Biomolecules. 2019;9:690. doi: 10.3390/biom9110690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Imran M., Aslam Gondal T., Atif M., Shahbaz M., Batool Qaisarani T., Hanif Mughal M., Salehi B., Martorell M., Sharifi-Rad J. Apigenin as an Anticancer Agent. Phytother. Res. 2020;34:1812–1828. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Guo Z., Cao W., Zhao S., Han Z., Han B. Protection against 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl Pyridinium-Induced Neurotoxicity in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells by Soyasaponin i by the Activation of the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/AKT/GSK3β Pathway. NeuroReport. 2016;27:730–736. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fouzder C., Mukhuty A., Mukherjee S., Malick C., Kundu R. Trigonelline Inhibits Nrf2 via EGFR Signalling Pathway and Augments Efficacy of Cisplatin and Etoposide in NSCLC Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2021;70:105038. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2020.105038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Choi M., Mukherjee S., Yun J.W. Trigonelline Induces Browning in 3T3-L1 White Adipocytes. Phytother. Res. 2021;35:1113–1124. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Farid M.M., Yang X., Kuboyama T., Tohda C. Trigonelline Recovers Memory Function in Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice: Evidence of Brain Penetration and Target Molecule. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16424. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73514-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Guo X., Wang L., Xu M., Bai J., Shen J., Yu B., Liu Y., Sun H., Hao Y., Geng D. Shikimic Acid Prevents Cartilage Matrix Destruction in Human Chondrocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018;63:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ertugrul B., Iplik E.S., Cakmakoglu B. In Vitro Inhibitory Effect of Succinic Acid on T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Lines. Arch. Med. Res. 2021;52:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim H.S., Yoo H.J., Lee K.M., Song H.E., Kim S.J., Lee J.O., Hwang J.J., Song J.W. Stearic Acid Attenuates Profibrotic Signalling in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Respirology. 2021;26:255–263. doi: 10.1111/resp.13949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Liu C., Weir D., Busse P., Yang N., Zhou Z., Emala C., Li X.M. The Flavonoid 7,4′-Dihydroxyflavone Inhibits MUC5AC Gene Expression, Production, and Secretion via Regulation of NF-ΚB, STAT6, and HDAC2. Phytother. Res. 2015;29:925–932. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chen Y., Guo S., Jiang K., Wang Y., Yang M., Guo M. Glycitin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury via Inhibiting NF-ΚB and MAPKs Pathway Activation in Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019;75:105749. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Baek S., Kim J., Moon B.S., Park S.M., Jung D.E., Kang S.Y., Lee S.J., Oh S.J., Kwon S.H., Nam M.H., et al. Camphene Attenuates Skeletal Muscle Atrophy by Regulating Oxidative Stress and Lipid Metabolism in Rats. Nutrients. 2020;12:3731. doi: 10.3390/nu12123731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Khoshnazar M., Parvardeh S., Bigdeli M.R. Alpha-Pinene Exerts Neuroprotective Effects via Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Mechanisms in a Rat Model of Focal Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020;29:104977. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Saeedi-Boroujeni A., Mahmoudian-Sani M.R. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Quercetin in COVID-19 Treatment. J. Inflamm. 2021;18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12950-021-00268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bharath B., Perinbam K., Devanesan S., AlSalhi M.S., Saravanan M. Evaluation of the Anticancer Potential of Hexadecanoic Acid from Brown Algae Turbinaria Ornata on HT–29 Colon Cancer Cells. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1235:130229. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Liu H.-M., Li H.-Y. Soybean-The Basis of Yield, Biomass and Productivity. InTech; London, UK: 2017. Application and Conversion of Soybean Hulls. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cabezudo I., Meini M.R., di Ponte C.C., Melnichuk N., Boschetti C.E., Romanini D. Soybean (Glycine Max) Hull Valorization through the Extraction of Polyphenols by Green Alternative Methods. Food Chem. 2021;338:128131. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.de Oliveira Silva F., Perrone D. Characterization and Stability of Bioactive Compounds from Soybean Meal. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015;63:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Alvarez M.V., Cabred S., Ramirez C.L., Fanovich M.A. Valorization of an Agroindustrial Soybean Residue by Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Phytochemical Compounds. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2019;143:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Freitas C.S., da Silva G.A., Perrone D., Vericimo M.A., Dos S. Baião D., Pereira P.R., Paschoalin V.M.F., del Aguila E.M. Recovery of Antimicrobials and Bioaccessible Isoflavones and Phenolics from Soybean (Glycine Max) Meal by Aqueous Extraction. Molecules. 2019;24:74. doi: 10.3390/molecules24010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nkurunziza D., Pendleton P., Chun B.S. Optimization and Kinetics Modeling of Okara Isoflavones Extraction Using Subcritical Water. Food Chem. 2019;295:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.05.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Nile S.H., Nile A., Oh J.W., Kai G. Soybean Processing Waste: Potential Antioxidant, Cytotoxic and Enzyme Inhibitory Activities. Food Biosci. 2020;38:100778. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Liu W., Zhang H.X., Wu Z.L., Wang Y.J., Wang L.J. Recovery of Isoflavone Aglycones from Soy Whey Wastewater Using Foam Fractionation and Acidic Hydrolysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:7366–7372. doi: 10.1021/jf401693m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Chua J.Y., Liu S.Q. Soy Whey: More than Just Wastewater from Tofu and Soy Protein Isolate Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;91:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Davy P., Vuong Q.V. Soy Milk By-Product: Its Composition and Utilisation. Food Rev. Int. 2020 doi: 10.1080/87559129.2020.1855191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Melini F., Melini V., Luziatelli F., Ficca A.G., Ruzzi M. Health-Promoting Components in Fermented Foods: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019;11:1189. doi: 10.3390/nu11051189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Dimidi E., Cox S.R., Rossi M., Whelan K. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2019;11:1806. doi: 10.3390/nu11081806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Şanlier N., Gökcen B.B., Sezgin A.C. Health Benefits of Fermented Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;59:506–527. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1383355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Tamang J.P., Shin D.H., Jung S.J., Chae S.W. Functional Properties of Microorganisms in Fermented Foods. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:578. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Adebo O.A., Oyeyinka S.A., Adebiyi J.A., Feng X., Wilkin J.D., Kewuyemi Y.O., Abrahams A.M., Tugizimana F. Application of Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)-Based Metabolomics for the Study of Fermented Cereal and Legume Foods: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:1514–1534. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gupta S., Lee J.J.L., Chen W.N. Analysis of Improved Nutritional Composition of Potential Functional Food (Okara) after Probiotic Solid-State Fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:5373–5381. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Chan L.Y., Takahashi M., Lim P.J., Aoyama S., Makino S., Ferdinandus F., Ng S.Y.C., Arai S., Fujita H., Tan H.C., et al. Eurotium Cristatum Fermented Okara as a Potential Food Ingredient to Combat Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54021-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Mok W.K., Tan Y.X., Lee J., Kim J., Chen W.N. A Metabolomic Approach to Understand the Solid-State Fermentation of Okara Using Bacillus Subtilis WX-17 for Enhanced Nutritional Profile. AMB Express. 2019;9:60. doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0786-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Mok W.K., Tan Y.X., Lyu X.M., Chen W.N. Effects of Submerged Liquid Fermentation of Bacillus Subtilis WX-17 Using Okara as Sole Nutrient Source on the Composition of a Potential Probiotic Beverage. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8:3119–3127. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Gupta S., Chen W.N. A Metabolomics Approach to Evaluate Post-Fermentation Enhancement of Daidzein and Genistein in a Green Okara Extract. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Gupta S., Chen W.N. Characterization and in Vitro Bioactivity of Green Extract from Fermented Soybean Waste. ACS Omega. 2019;4:21675–21683. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Ghanem K.Z., Mahran M.Z., Ramadan M.M., Ghanem H.Z., Fadel M., Mahmoud M.H. A Comparative Study on Flavour Components and Therapeutic Properties of Unfermented and Fermented Defatted Soybean Meal Extract. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5998. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62907-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Azi F., Tu C., Meng L., Zhiyu L., Cherinet M.T., Ahmadullah Z., Dong M. Metabolite Dynamics and Phytochemistry of a Soy Whey-Based Beverage Bio-Transformed by Water Kefir Consortium. Food Chem. 2021;342:128225. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Yang J., Wu X.B., Chen H.L., Sun-Waterhouse D., Zhong H.B., Cui C. A Value-Added Approach to Improve the Nutritional Quality of Soybean Meal Byproduct: Enhancing Its Antioxidant Activity through Fermentation by Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens SWJS22. Food Chem. 2019;272:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Liang S., Jiang W., Song Y., Zhou S.F. Improvement and Metabolomics-Based Analysis of d-Lactic Acid Production from Agro-Industrial Wastes by Lactobacillus Delbrueckii Submitted to Adaptive Laboratory Evolution. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:7660–7669. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kupski L., Telles A.C., Gonçalves L.M., Nora N.S., Furlong E.B. Recovery of Functional Compounds from Lignocellulosic Material: An Innovative Enzymatic Approach. Food Biosci. 2018;22:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Yang S.O., Kim S.H., Cho S., Lee J., Kim Y.S., Yun S.S., Choi H.K. Classification of Fermented Soymilk during Fermentation by 1H NMR Coupled with Principal Component Analysis and Elucidation of Free-Radical Scavenging Activities. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009;73:1184–1188. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Simu S.Y., Castro-Aceituno V., Lee S., Ahn S., Lee H.K., Hoang V.A., Yang D.C. Fermentation of Soybean Hull by Monascus Pilosus and Elucidation of Its Related Molecular Mechanism Involved in the Inhibition of Lipid Accumulation. An in Sílico and in Vitro Approach. J. Food Biochem. 2018;42:e12442. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.