Abstract

Objectives

We synthesise evidence on sexual harassment from studies in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) to estimate its prevalence and conduct a meta-analysis of the association between sexual harassment and depressive symptoms.

Methods

We searched eight databases. We included peer-reviewed studies published in English from 1990 until April 2020 if they measured sexual harassment prevalence in LMICs, included female or male participants aged 14 and over and conceptualised sexual harassment as an independent or dependant variable. We appraised the quality of evidence, used a narrative syntheses approach to synthesise data and conducted a random effects meta-analysis.

Results

From 49 included studies, 38 focused on workplaces and educational institutions and 11 on public places. Many studies used an unclear definition of sexual harassment and did not deploy a validated measurement tool. Studies either used a direct question or a series of behavioural questions to elicit information on acts considered offensive or defined as sexual harassment. Prevalence was higher in educational institutions than in workplaces although there was high heterogeneity in prevalence estimates across studies with no international comparability. This posed a challenge for calculating an overall estimate or measuring a range. Our meta-analysis showed some evidence of an association between sexual harassment and depressive symptoms (OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.11 to 2.76; p=0.016) although there were only three studies with a high risk of bias.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to assess measurement approaches and estimate the prevalence of sexual harassment across settings in LMICs. We also contribute a pooled estimate of the association between sexual harassment and depressive symptoms in LMICs. There is limited definitional clarity, and rigorously designed prevalence studies that use validated measures for sexual harassment in LMICs. Improved measurement will enable us to obtain more accurate prevalence estimates across different settings to design effective interventions and policies.

Keywords: depression & mood disorders, public health, sexual and gender disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review to assess measurement approaches and estimate the prevalence of sexual harassment across settings (workplace, educational and public places) in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

We also contribute the first pooled estimate of the association between sexual harassment and depressive symptoms in LMICs.

We identified several conceptual and methodological issues in the included studies that limit the conclusions that can be drawn from the review. Furthermore, heterogeneity in prevalence estimates is likely to further reduce the comparability of findings.

Most studies used non-probability sampling and did not provide information on the representativeness of their samples.

If sexual harassment did not feature in the abstract and was a secondary objective in studies, this review might have missed it resulting in publication bias.

Introduction

In the last two decades, the pervasiveness and costs of sexual harassment has become a growing concern globally.1 This has been precipitated by the #MeToo and Times Up movements in the mid-2010s that increased global awareness of offending actions that women and girls experience in their daily personal and working lives. The discussions around these movements, however, have predominantly taken place in high-income countries or affluent urban areas in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC).2 Depending on the setting, sexual harassment can encompass a range of behaviours and practices of a sexual nature, such as unwanted sexual comments or advances, sexual jokes, displaying pictures or posters objectifying women, physical contact or sexual assault.3 Sexual harassment is often experienced in the workplace or in educational settings and women are more likely to experience sexual harassment than men.2

The WHO defines sexual harassment as ‘any unwelcome sexual advance, unwelcome request for sexual favour, verbal or physical conduct or gesture of a sexual nature, or any other behaviour of a sexual nature that might reasonably be expected or be perceived to cause offence, humiliation or intimidation to the person’.4 Furthermore, institutions like the International Labour Organisation (ILO) have used a similar definition with an explicit mention of the workplace and two additional categories: ‘quid pro quo’ or ‘hostile working environment’. Quid pro quo sexual harassment is when a worker is asked for a sexual favour and submitting to or rejecting that request is used to decide about that worker’s employment. Hostile working environment harassment covers conduct that creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating working environment.5 Sexual harassment may be perpetrated by different individuals, including teachers, colleagues, supervisors, subordinates and third parties.3 In line with the ILO definition, the hierarchical and gendered power relations within occupational or educational settings have naturalised a sexual contract in which some male colleagues or academics consider it a right to demand sex with female juniors or students in return for career progression or grades.6

Some studies, primarily from high-income settings, have shown that those who report experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace typically report decreased job satisfaction,7 psychological distress including anxiety, anger and depression,8 as well as physical distress such as weight loss, fatigue and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.9 Economic hardship due to job loss can occur when victims quit their position or are fired as retaliation for reporting; this, alongside lost opportunities for career advancement are serious economic consequences of sexual harassment. Organisations in which harassment is prevalent suffer from absenteeism, increased staff turnover, lower job performance and productivity, increased legal fees and negative public image.10 Sexual harassment on university campuses has been shown to be a factor impeding female participation and satisfaction with their studies.6 A recent systematic review from studies from the USA showed that exposure to sexual harassment in higher education leads to physical and psychological consequences for individuals, such as irritation, anger, depression, stress, discomfort, feelings of powerlessness and degradation,11 physical pain,12 unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases13 and increased alcohol use.14

Historically, research on sexual harassment focused on the workplace in high-income countries, like the USA.15 16 For instance, the US National Health and Social Life Survey (1992) showed that 41% of women and 32% of men experienced workplace sexual harassment.2 17 Likewise, a recent meta-analysis of workplace sexual harassment in the USA revealed that 58% of women had been affected.2 15 The measurement tools for estimating the prevalence of sexual harassment have been primarily developed and tested in high-income countries—with uncertain relevance for women in the Global South.16 Relatedly, the ILO and the WHO measurement tools to measure abuses globally are applicable only for specific spheres of life, for example, work or education.18 There is less research on the prevalence of sexual harassment in LMICs and across different spheres of lives. The limited research has shown important differences across countries in prevalence rates. For example, a survey of the general population in China found that 12.5% of all women had experienced past year sexual harassment.2 19 In contrast, a higher prevalence (47%) of workplace sexual harassment was found among women faculty and staff, in a study of college employees in Ethiopia.2 9 These differences likely reflect cultural differences in the frequency of harassment. But they can also reflect differences in the labelling of specific behaviours as harassment. This is especially likely when studies do not ask specific questions about types of behaviour that may constitute sexual harassment.2

Furthermore, it is difficult to make direct comparisons in prevalence rates across countries because of methodological differences between studies2 in, for example, the way that sexual harassment is defined, the way that samples are collected (eg, convenience vs representative samples), the type of workplace setting and the wording and grouping of survey questions.11 15 The consequence of these challenges is that prevalence measures for sexual harassment may vary widely. In order to estimate the true percentage of women experiencing sexual harassment in different settings and countries across the Global South, there is a need to systematically synthesise the current published evidence, comparing across contexts with a view to providing insights to improve measurement practices for future studies. To date, no study has systematically reviewed prevalence estimates in peer-reviewed research on sexual harassment across different settings (workplace, education and public spaces) in LMICs. The purpose of this study is to address this gap through the review and synthesis of prevalence studies on sexual harassment published from January 1990 to April 2020 to highlight evidence gaps for measurement studies.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Our systematic review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews, with the record number CRD42020176881. We searched key public health, health sciences and health economics databases—Medline, Embase, Global Health, Psycinfo, EconLit, Scopus, Web of Science and Social Policy and Practice on 14 April 2020. Search terms were the names of all countries in low and middle income settings and the term ‘sexual harassment’ in any abstract or title published in English on or after 1 January 1990. We also screened the reference lists of included papers. Our detailed search strategy is included as online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjopen-2020-047473supp001.pdf (340.4KB, pdf)

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) were published in English, (2) were conducted in LMICs (as defined by World Bank country classifications)20 at any point from 1 January 1990 to April 2020; (3) measured the prevalence of sexual harassment in peer-reviewed studies based on either a cross-sectional survey, case–control study or cohort study; (4) included female or male participants aged 14 and over and (5) conceptualised sexual harassment as an independent or dependant variable. Studies were excluded if they were: (1) non-English studies, (2) conducted in high-income countries, (3) case studies, legal/policy frameworks, theoretical pieces, qualitative studies, conference abstracts, dissertation abstracts, theses, and book chapters or (4) studies focused on groups such as those in military services, in war zones, or in refugee camps as these were population groups and situations with a higher prevalence of sexual harassment owing to their unique situation. We also excluded five studies that did not include a measure of sexual harassment or did not include the prevalence estimate despite a mention in the abstract.21–25

Data screening, extraction and quality appraisal

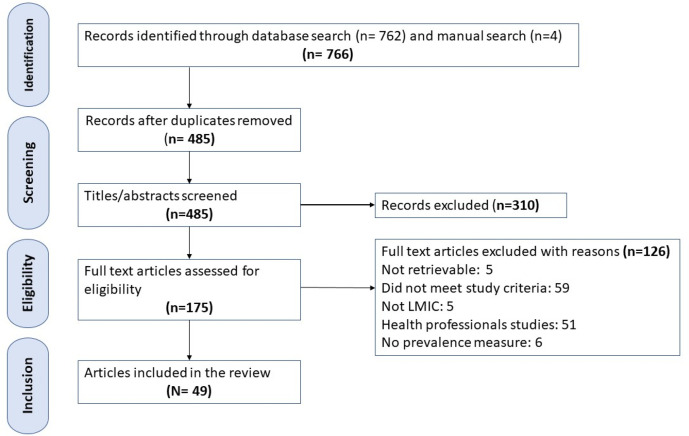

The first author (MR) and last author (HS) initially screened records by title and abstract according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text articles were then reviewed by one reviewer (MR) for eligibility and then double-checked by a second reviewer (HS). Disagreements about inclusion of articles were discussed by MR and HS until consensus was reached on articles to include. For instance, during the full-text screening, we excluded studies on healthcare professionals (eg, nurses and doctors) as this population was well studied with two meta-analyses focused exclusively on this group in China26 27 and one on nurses globally.28The final set of included full-text articles was formally appraised by two reviewers (MR and HS). Data from full-text sources were extracted using the following headings: first author and year; country; study setting; description of study sample; study design and sample number; information provided on sexual harassment–study definition, measurement approach, reporting period, prevalence estimates, frequency of acts and main perpetrator; outcomes (eg, sleep disorders or mental health effects, if measured), outcome direction and nature of effect. The study selection process, including the number of study abstracts and full-texts screened with reasons for exclusion, is depicted in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart as figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection. LMICs, low-income and middle-income countries; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Using criteria adapted from Hoy et al29 the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist29 and our own study criteria, two reviewers appraised the quality of included studies. The completed quality appraisal table (please see online supplemental appendix 1) includes nine questions about study quality: whether studies answered our research question, sampling strategy, participation rates and any bias in the measurement of prevalence of sexual harassment and reported results. Papers received a grade of either 0 (low) or 1 (high) for each question, giving a maximum total score of 9. Studies with a total score 0–3 were considered low quality, 4–6 were of moderate quality and 7–9 were of high quality. No studies were included or excluded from the review based on their quality score. We have followed PRISMA guidelines for this review and include the completed 2020 checklist (please see online supplemental appendix 1).

Data analysis

We used a narrative synthesis textual approach to synthesise data as our study was focused on resolving questions for measuring the prevalence of sexual harassment and not the effectiveness of an intervention.30 We grouped studies around measures used to report prevalence estimates of sexual harassment and assessed this across different studies. We also compared the findings with our conceptual understandings of sexual harassment to interpret the findings. We presented the results after assessing the methodological quality of the included studies, and critically reflected on the strengths and weaknesses of the approaches used, including limitations such as evidence gaps, quality of the evidence and biases in the review process.

Given the high heterogeneity across studies, we conducted a meta-analysis of only three studies that presented ORs for exposure to sexual harassment on the outcome of poor mental health, namely depressive symptoms. We focused on depressive symptoms, as from all the studies that measured symptoms of poor mental health, only three studies were similar in their study definition, had extractable information and showed associations with symptoms of depression. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to provide a pooled OR and 95% CI using Stata V.15, specifically the ‘metan’ command. This pooled OR was calculated based on the results of three studies;9 31 32 which, in total, provided three ORs for the risk of depression among sexually harassed women. We used a random-effects model due to the perceived variability in populations and methods used in the included studies.

Results

The study selection process is presented in figure 1. Our literature searches returned 485 unique records, of which 310 were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. Full-text copies of the remaining 175 references that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved. After further screening, 49 papers were retained for inclusion. Of the 49 papers, 48 were identified from searches of electronic databases and one from a citation search.

Description of included studies

Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of all included studies. Except for two studies published between 2000 and 2020; a majority (n=35) of the studies were published after 2010. In terms of geographic spread, most studies were either from Asia (n=26) and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (n=22) with only three studies from Latin America and four from the Middle East and North Africa region. Studies (77.5%, n=38) were primarily focused on either a workplace or educational setting, with only 11 studies focused on public spaces, such as public transport, streets or the community. Among educational settings, most were higher educational institutions with four studies33–36 focused on adolescents at secondary schools. All, but two studies were observational with cross-sectional surveys; only two studies had a longitudinal design.37 38 Most studies (n=41) focused on surveys representative of the population in specific settings; samples of males and females working in universities, in public sector jobs or male and female students at schools or universities. Seven studies focused on special populations with increased vulnerabilities based on their occupation or life situation, for instance, female bar workers,31 frontline hotel employees,37 homeless individuals,39 female migrant workers in garment factories,40 female domestic workers40 or clergy members.41 Most studies had small sample sizes with less than 500 participants (n=28), some were medium size samples of 500–5000 (n=18) and a handful of studies with sample sizes above 5000 (n=3). Only four studies were nationally representative.19 36 42 43

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies (n=49)

| Reference | Study setting | Sample | Sample size | SH definition | Measurement approach | Scales | Sex disaggregated | Perpetrator information | Frequency of acts/experience | ||||||||

| Workplace | Educational | Public places | Community/other | General | Special populations | Less than 500 | More than 500 | Included | Direct query | List of behaviours or acts | Categories of physical, non-verbal, verbal | Validated | Not validated | Yes | Included | Included | |

| Luo, 199644 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Tang et al, 199650 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Mayekiso and Bhana, 199751 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Shumba et al, 2010 52 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Fineran et al, 200335 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Fawole et al, 200538 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Obozokhai, 200553 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Parish et al, 200619 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Puri and Cleland, 200740 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Merkin 20087 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Marsh et al, 20099 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| De Souza and Cerqueira, 200980 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Owoaje and Olusola-Taiwo, 200954 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Koehlmoos et al, 200939 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Premadasa et al, 201165 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Owoaje et al, 201155 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Lahsaeizadeh and Yousefinejad, 201281 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Dhlomo et al, 201256 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Hutagalang and Ishak, 201266 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Norman et al, 201257 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Fernandes et al, 201232 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Norman et al, 201341 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| de Puiseau and Roessel, 201334 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Norman et al, 201358 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Haile et al, 201382 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Park et al, 201342 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Austrian and Muthengi, 201433 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Maurya and Agarwal, 201445 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Mamaru et al, 201567 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Tobar et al, 201559 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Kunwar et al, 201568 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Vuckovic et al, 20173 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Sahraian et al, 201646 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Tripathi et al, 201647 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Zhang et al, 201643 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Talboys et al, 201760 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Xie et al, 201769 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Tripathi et al, 201770 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Dar and Hasan, 201848 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Aina and Kulshrestha, 201849 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Mabetha and De Wet et al, 201836 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Ul Haq et al, 201876 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Akoku et al, 201931 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Murshid and Murshid, 201961 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Zhu et al, 201937 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Saberi et al, 201962 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Gautam et al, 201971 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Huang et al, 201963 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Oni et al, 201964 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

Definition of sexual harassment

Despite an intention to measure sexual harassment, 35% (n=17) of identified articles had no listed definition of sexual harassment. This rendered their conceptualisation of sexual harassment as unclear. For studies that defined sexual harassment, these varied from a two-part objective (the identification of the activity) and subjective (the person’s perception) definition of sexual harassment, to a ‘lay’ definition of sexual harassment that included types or classes of behaviour; ‘unwanted sexual related behaviour’ or ‘unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature’ or ‘intimidating verbal or physical sexual advances’. These studies sought to find out behaviours that constitute harassment, and those that do not.16 Despite not having an explicit definition of sexual harassment, one study Tripathi et al, 2016 acknowledged that a range of acts ranging in severity can come under its purview, for example, from passing comments about a girl among a group of friends to sexual assault and that there are subjective perceptions of whether the actions are sexual harassment or not, especially where no physical contact is involved.5

Eight studies in this review drew on the definition by Fitzgerald et al16 that assumes classes of behaviours that constitute sexual harassment. This definition was initially conceptualised for the workplace but is applicable to other settings. It is composed of three related but conceptually distinct dimensions, gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion.

Gender harassment is considered as the most common type of sexual harassment. It consists of insulting verbal and nonverbal behaviours conveying derogatory, hostile, or degrading attitude towards women based on their gender; unwanted sexual attention consists of verbal and nonverbal behaviours that are offensive, unwanted, and unreciprocated; sexual coercion entails sexual advances and makes the conditions of employment (or education, for students) contingent on sexual cooperation.16 In line with the ILO definition, harassing behaviours can be either direct (targeted at an individual) or ambient (a general level of sexual harassment in an environment). Furthermore, a harasser may be male or female, and harassment is not limited to men harassing women, although this is the most common.16Please see online supplemental appendix 1 for a range of study-specific definitions of sexual harassment.

Measurement approach for sexual harassment

The measurement approach in studies was either a direct query method with the question ‘have you been sexually harassed?’ (n=14)3 7 9 32–34 42 44–49or a series of questions where participants had to indicate whether they had experienced behaviours or acts considered offensive and consistent with sexual harassment (n=26).9 31 35–39 41 50–64 Nine studies19 43 65–71 conceptualised sexual harassment as physical, verbal and non-verbal acts; physical consisted of purposely bumping or hurting someone, acting indecently and inappropriate touching, verbal consisted of inappropriate sexual comments about body parts, telling sexual or dirty jokes and asking a favour for having sexual intercourse; and non-verbal consisted of displaying inappropriate pictures through email/social media, inappropriate eye contact. We excluded three studies that reported measuring sexual harassment, but measured sexual violence explicitly defined and measured as sexual violence or sexual abuse in the study with forced sex or rape72–74 (see table 1).

Many studies did not deploy a validated tool, but either used a direct question or a series of behavioural questions (see table 1). These were preceded sometimes with a single ‘gate question’ to assess an entire class of events where only respondents with a positive response receive additional questions to clarify the nature of the event(s). Sixteen studies used existing sexual harassment scales from studies conducted in high-income settings, particularly North America. Examples of some of the scales are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Sexual harassment scales validated in high-income setting used in prevalence studies across low-income and middle-income settings

| Validated scales | Description | Study references |

| Adapted version of the 25-item Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ), Fitzgerald et al,16 Berdahl and Moore,83 Murry and Sivasubramaniam,84Stark85 2002 for workplace and educational. | A questionnaire that combines a series of questions across three dimensions:

|

Eight studies 37 41 45 56–58 63 80 |

| Modified version of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Educational Foundation questionnaire on sexual harassment in college campuses.86 | Sexual harassment experiences were asked across four categories:

|

Three studies 53 54 76 |

| Eve-Teasing Questionnaire-Mental Health (ETQ-MH) in public places. | Consisted of questions about: (a) eve teasing exposure, nature, timing, and intensity; (b) chronicity that delineates one time or ongoing harassment. Actual questions were: (a) Have you ever been eve-teased? (b) When was the last time you were eve-teased? (c) I am going to read you this list of behaviours. As I read each one, can you tell me if you have been the target of any of these in the past year by men/boys: staring; stalking; making vulgar gestures; passing an insulting or threatening comment; pushing or brushing by accident. |

One study 60 |

| Sexual harassment question in Workplace Violence questionnaire created by the International Labour Organisation/WHO/International Council of Nurses/Public Services International (ILO/WHO/ICN/PSI).18 | Direct question on experiencing sexual harassment in the past

|

Two studies46 62 |

| WHO’s adolescents sexual behaviour questionnaire.87 | Questions on sexual harassment:

|

One study40 |

| Rautio et al88 medical student questionnaire. |

|

One study 55 |

| Braine et al89 sexual harassment questionnaire adapted for university students. | Ten behaviours that may constitute sexual harassment (uncategorised).

|

One study46 |

Most studies (n=35) did not ask about frequency of behavioural acts at all. None of the studies provided information on the cases of sexually harassing behaviours that could present a better indication of the pervasiveness of the behaviour. For example, an unwanted comment received once differs from one received regularly over a month or few months. Thus, an emphasis on specific patterns of behaviour rather than just a focus on singular incidents is a better measure for pervasiveness. Studies that used the adapted versions of the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ) scale assessed the number of times or the frequency with which different types of harassment are experienced on a Likert scale, either 0–4 or 0–5 (0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=often, 4=almost always) or the Eve-Teasing Questionnaire-Mental Health (ETQ-MH) scale delineated one time versus on-going. Perpetrator data are important to understand sexual harassment perpetration and the power differential with the survivor of sexual harassment. Fifteen studies did not ask for any information about perpetrators. In workplace settings, 11 studies mentioned perpetrators of the opposite sex and more often a superior at the workplace. In educational settings, when the study was collecting information from students, most studies (n=7) reported that most students reported a superior (lecturer or a senior student).36 41 50–52 54 65 In some studies (n=2) with staff members, it was often a head of department of the opposite sex. In public places and community settings, three studies referred to strangers of the opposite sex as perpetrators.33 70 71

Prevalence of sexual harassment

The definition and the measurement approach used by studies is crucial to determining prevalence rates. However, the measurement dimensions and techniques used to measure prevalence rates across these studies are heterogeneous with no international comparability. This presented a challenge for calculating an overall estimate or measuring a range.

Table 3 provides prevalence measures by measures, scale, setting and population. In studies that used only the direct query method, the prevalence of sexual harassment (as defined by the studies) ranged from 0.6% to 26.1%. Among studies where questions were based on behavioural acts, the prevalence range was wide-ranging from 14.5% to 98.8% indicating that studies were able to capture a higher prevalence for certain individual behaviours or acts, such as suggestive comments, inappropriate staring, unwanted touching and sexual calls. Only three studies9 58 63 had a list of behavioural questions, followed by a direct question about whether participants thought ‘they had been sexually harassed?’ or ‘whether they consider the above behaviours as sexual harassment?’. It appeared that the prevalence rates for experiencing offensive acts were higher when followed up in the survey with the direct question. In studies that asked questions based on physical, verbal and non-verbal categories, the ranges were: physical (1.6%–42.3%), verbal (8.3%–90.4%), non-verbal (11.3%–80.1%) (see table 3). There was variation in prevalence rates by the type of validated scale, as seen in the following examples. For studies that adapted different types of the SEQ scale with a range in the types of questions included, the overall prevalence range from six studies was 6.2%–28% with only one study63 reporting 78%; the modified version of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Educational Foundation questionnaire, the range was high from 69.8% to 83%, the ETQ-MH for one study where the prevalence was 48.3% ever experienced and 37.1% past year experience; for the direct query method in the ILO/WHO/ICN/PSI studies were 26.1% aggregate in one study46 and 12% females in another study62 (see table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of sexual harassment by measures, setting and population

| Type | Prevalence range | Reference |

| Measurement approach | ||

| Direct query method | 0.6%–26.1% | 3 7 9 32 34 42 44–48 76 |

| List of behaviours or acts (wide-ranging behaviours). Most common below: |

14.5%–98.8% | 9 31 35 39 41 50 53–64 |

| Suggestive comments | 85%–90% | |

| Inappropriate staring | 70%–90% | |

| Unwanted touching | 46%–70% | |

| Categories (physical, non-verbal, verbal) | 19 43 65–71 | |

| Physical |

1.6%–42.3% | |

| Verbal | 8.3%–90.4% | |

| Non-verbal | 11.3%–80.1% | |

| Settings | ||

| Workplace | 1%–52% | 3 7 9 31 37 38 40 42 44 45 47 62 66 68 80 |

| Educational | 14.4%–73% | 34–36 49 50 52 54–56 59 63–65 67 69 76 82 |

| Public places | 25%–78% | 39 70 71 |

| Community/other | 11.9%–83% | 19 30 31 41 55 59 81 |

| Special populations | ||

| Female bar workers | 98.8% in the past 3 months | 31 |

| Homeless adult population | 62.9% in the time-period of being homeless | 39 |

| Clergy and lay members | 73% in the past 12 months | 41 |

| Female domestic workers | 25% in the past 12 months | 80 |

| Female migrant workers | 12.2% ever experience | 40 |

| Female apprentices (hairdressers, tailors) | 22.9% (time-period not specified) | 38 |

| Female patients in hospitals (with mental health issues)* | 65% (time-period not specified) | 48 |

*As reported by relatives.

There was variation in prevalence rates by type of setting; workplace settings ranged from 1% to 52% depending on the context of the workplace and the population group. However, the methods or techniques used to calculate prevalence varies noticeably across studies in these settings. In educational settings, it ranged from 14.4% to 73%, but studies measured or categorised dimensions differently and it was also based on the type of study population, such as adolescent girls and boys. In the three studies39 70 71 done in public places, the range was 25%–78%. In the seven studies done in the community, the prevalence range was 11.9%–83%.19 32 33 43 53 60 61 In studies with special populations (n=7) who were more vulnerable to experiencing sexual harassment, based on their occupation or life situation, average prevalence rates were reported to be higher than in studies with a general sample with lower estimates of prevalence. For example, the prevalence of sexual harassment among female bar workers was 98.8% and among clergy and lay members 73% (see table 3).Online supplemental appendix 1 provides further details on study characteristics and information on sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment and associations with mental health

Thirteen out of 49 studies measured outcomes associated with sexual harassment. These were positive associations with symptoms of poor mental health (n=8),9 31 32 37 45 57 58 67 risky sexual behaviours (n=1),36 work-related life satisfaction or stress (n=2),42 66 student’s quality of life (n=1)69 and loss of trust in other religious members (n=1).41 Of the studies that measured symptoms of poor mental health with extractable information, three studies showed associations with symptoms of depression,9 31 32 one study showed associations with psychological distress67 and one with work-related sleep problems42 (see table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms, psychological distress and work-related sleep problems among sexually harassed women

| Author, year | Setting | Outcome | Instrument and threshold to assess mental distress | OR and 95% CI |

| Akoku et al (2019)31 | Workplace | Depressive symptoms | Five-item Mental Health Inventory scale (MHI-5) | Experienced inappropriate staring from male customers (aOR: 3.08; CI: 1.9 to 5.0) Repeated demands for dates despite a rejection (aOR: 1.61, CI: 1.04 to 2.49) |

| Fernandes et al32 (2012) | Youth (aged 16–24) community survey | Common mental disorders (CMDs) defined usually by depression (including unipolar major depression), anxiety and somatoform disorders | General health questionnaire with 12 items (GHQ-12). Cut-off score=5 and above. | Sexual harassment (aOR: 2.25; CI: 1.63 to 3.1) |

| Marsh et al (2009)9 | Workplace | Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) quick depression assessment tool. 0=never, 1=several weeks in the past year, 2=more than half of past year, 3=nearly the whole year. Summative score divided into summative categories. |

Workplace abuse and sexual harassment (OR: 8.0; 95% CI: 1.1 to 60.8 |

| Mamaru et al (2015)67 | Educational | Psychological distress | Self-reported questionnaire (SRQ-20) (WHO) | Physical sexual harassment (aOR: 3.9; CI: 1.9 to 7.9) Non-verbal sexual harassment (aOR: 12.1; CI: 5.2 to 28.2) |

| Park et al42 (2013) |

Workplace | Work-related sleep problems | Sleep problems assessed by single item ‘Do you currently suffer from work-related sleep problems?’ | Sexual harassment (aOR: 6.99; CI: 3.87 to 12.6) |

aOR, adjusted OR.

One study showed that students who were physically (aOR=3.950, 95% CI: 1.979 to 7.884) and non-verbally harassed (aOR=12.1, 95% CI: 5.190 to 28.205) had four and 12 times higher odds of experiencing psychological distress, respectively.67 Another study in the workplace showed that those who experienced sexual harassment experienced close to seven times higher odds of work-related sleep problems.42

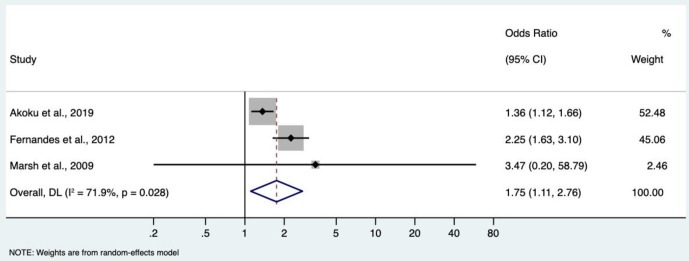

For the association between sexual harassment and symptoms of depression, we calculated a random-effects meta-analysis to obtain a pooled OR. The pooled OR was 1.75 (95% CI: 1.11 to 2.76; p=0.016), showing a significant relationship between exposure to sexual harassment and symptoms of depression. This pooled OR showed a heterogeneity of 71.9%, with a p value of 0.028 suggesting that there was some heterogeneity. A forest plot presenting the results of the random effects meta-analysis of three studies presenting ORs for the association between sexual harassment and symptoms of depression is shown in figure 2. Please note Akoku et al presents seven ORs for the association between various forms of sexual harassment and the outcome of depressive symptoms. These seven ORs were pooled using a fixed-effects meta-analysis to produce one overall OR to represent the findings of this study. The study does not provide frequency distributions for the variables thus we were unable to create an overall OR using the exact numbers.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the association between sexual harassment and symptoms of depression.

Discussion

In our systematic review on sexual harassment in LMICs, most studies were published in the past decade (>2010) indicating that the issue has gained prominence recently, in LMICs. Studies were primarily convenience samples focused on either a workplace or educational setting and from Asia and SSA, with only three studies from Latin America. All the studies were cross-sectional surveys (only two studies used a longitudinal design) and four studies were nationally representative samples. Our review has shown that a third of the studies intended to measure the prevalence of sexual harassment without a clear definition. Even when studies included a definition, either from the WHO or the ILO or Fitzgerald’s (1995) definition, there was variation between studies on the conceptualisation of sexual harassment and ambiguity around its measurement. In particular, due to the subjective nature of sexual harassment, and a participant’s perception of their experience versus the legal definition, there were challenges to measuring sexual harassment and obtaining a true prevalence measure.75 To emphasise the ambiguous nature of definitions, in our literature search, three studies conflated sexual harassment with sexual violence when discussing measurement. We have excluded these studies from the final review but have raised it here to highlight a lack of clarity around the conceptualisation of sexual harassment. We acknowledge that sexual harassment and sexual violence may have overlapping constructs, particularly the unwanted sexual nature of physical contact, and we do not expect to clearly distinguish them in every case as they lie on a continuum of severity. However, sexual violence tends to be more severe acts, such as forced sex or attempted rape. Furthermore, a conflation of sexual harassment and sexual violence has implications for measurement, as individuals may not report the non-penetrative experiences that characterises sexual harassment.

The prevalence rates of sexual harassment varied by the type of setting with higher educational institutions having a higher prevalence range than the workplace. However as most studies used convenience samples with small sample sizes, it is difficult to draw conclusions. For the 30 studies that included males and females, 19 studies disaggregated prevalence rates by sex and in all studies, except one study76 females reported a higher prevalence of sexual harassment than males. In the one study76 when there was higher reporting by males, it was related to the age difference between the individuals and the perpetrators who were in positions of authority. This aligns with evidence from high-income settings that some behaviours are more likely to be perceived as harassing by both sexes if they are engaged in by someone who has higher status or formal authority over the harassed. When there is no status differential, the immediate threat is not apparent and this may elicit actual gender differences in the interpretation of events; men may perceive the behaviour as harmless social interaction, whereas women may perceive an element of threat.77 However, it is difficult to conclude that females experience a higher prevalence of sexual harassment than men as this varies by study setting. For instance, a global meta-analysis of nurses and workplace sexual harassment conclude that compared with male nurses, female nurses reported a lower prevalence of sexual harassment. However, this may also have to do with under-reporting of sexual harassment by females due to reasons, such as shame and embarrassment.28

There was also wide variation by the type of measurement approach (direct query vs behavioural acts or categories). Studies were able to capture a higher prevalence for certain individual behaviours or acts, such as suggestive comments, inappropriate staring, unwanted touching and sexual calls, than with only a direct question asking if they have been sexually harassed. Furthermore, three studies that used the SEQ scale used a combination approach that included the list of offensive behaviours, followed by one question on whether the individual who responded positively to one or more instances of inappropriate behaviour acknowledges that they have experienced sexual harassment. Surprisingly, the studies show that a high percentage of individuals have experienced two or more harassing behaviours (eg, unwanted touching or suggestive comments), but a lower percentage acknowledge that their experience is sexual harassment. For example, in Huang et al63, while 78% of 1075 respondents experienced at least one situation of harassment listed in the SEQ-China, only 43% reported having been sexually harassed when asked it directly.63 This suggests the need to consider other factors for this discrepancy, such as cultural norms and normalisation of the practice or the power dynamic between the perpetrator and the victim. Stockdale et al78 clarify this by describing the discrepancy between reporting a harassment-like experience and reporting that one has actually been sexually harassed as the acknowledgement process.78 They found a higher likelihood of an individual acknowledging sexual harassment if they had experienced unwanted sexual attention, such as sexual looks or gestures, if (a) the offences were frequent and pervasive, (b) the respondent was harassed by a higher status perpetrator and (c) the respondent was a woman.78 Thus, individuals harassed by perpetrators that maybe considered to be higher in status (with more power) would be more likely to label their experience as sexual harassment than individuals harassed by perpetrators of the same or lower status. In this review, when the information on perpetrators was available, the studies indicated offensive behaviours by perpetrators of lower status compared with higher status perpetrators. Students and coworkers were mentioned most frequently as being perpetrators in educational and workplace settings. Moreover, in those studies that measured it, peer harassment was far more common than harassment by superiors.35 36 50 One explanation for low acknowledgement is that most incidents involve offensive behaviours by perpetrators that are not normally considered to be sexual harassers (eg, peers).78 This, however, does not change the fact that the behaviours they experienced were offensive and unacceptable. Furthermore, apart from measurement issues being a reason for under-reporting, in the workplace, a fear of a negative impact on jobs, feeling embarrassed, a fear of being discriminated against by work colleagues or a fear that their report will not be taken seriously are other reasons for low reporting rates. In school settings, fear of negative reprisal from teachers and peers, normalisation of sexual harassment and not being able to recognise it can also result in under-reporting.

There is strong agreement that the consequences of sexual harassment are serious and complex, irrespective of whether the focus of research is on employees or students and staff in higher education.11 Research from high-income countries has shown the impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms.79 In our review, there is evidence of a significant negative association between sexual harassment and symptoms of depression. There however needs to be more empirical research from LMICs by setting and different mental health outcomes, such as risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as diminished self-esteem, self-confidence, and psychological well-being.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to assess the prevalence and measurement of sexual harassment in LMICs, with the first pooled estimate of the association between sexual harassment and depression in LMICs. In terms of limitations, our review has not included non-peer reviewed literature or articles not published in English, potentially leading to an underrepresentation of non-English speaking countries. Using a low, moderate and high cut-off for methodological quality could imply that all criteria carry equal weight, and some studies may have been misclassified as regards their overall quality. We also identified several conceptual and methodological issues in the included studies that limit the conclusions that can be drawn from the review. Following quality appraisal by two reviewers, 17 of the 49 included papers scored <4/9 (low/moderate) on questions relating to selection bias. Furthermore, we found that most studies used non-probability sampling and did not provide information on the representativeness of their samples. Finally, heterogeneity in studies’ definitions of sexual harassment is likely to further reduce the comparability of findings. A further definitional complexity is around the conflation of sexual harassment with sexual violence by some studies. While there are overlaps between sexual harassment and sexual violence particularly around unwanted sexual comments or advances, sexual violence tends to encompass more coercive and severe penetrative behaviours such as rape, whereas sexual harassment tends to focus on less physically severe but offensive behaviours that can create a hostile environment for victims of sexual harassment. Even though our search were limited to studies that used the term sexual harassment, there were some studies that indicated measuring sexual harassment but referred to sexual violence. Hence, by conflating sexual violence and sexual harassment, we risk the under-reporting or non-measurement of sexual harassment with negative impacts on women and girls. Also, if sexual harassment was only a secondary objective of studies and did not feature in the abstract, this review might have missed it, resulting in publication bias. Finally, our meta-analysis of sexual harassment and depression must be interpreted with caution. First, the three studies were deemed homogeneous enough to be included in a meta-analysis because they all presented ORs for the association between sexual harassment and depression; however, in each of these studies, different definitions of sexual harassment were used, along with different methods of assessing symptoms of poor mental health. Second, both Akoku et al and Fernandes et al were concluded in the quality assessment to have a high risk of bias, with Marsh et al9 concluded as showing a moderate risk of bias. Both Marsh et al and Akoku et al31 did not use random samples in their study and were not representative of their target population. In Fernandes et al, the study lacked both clear definitions of sexual harassment and clear descriptions of how it was measured. Finally, only three measures of effect were included and one9 presented only a non-significant unadjusted OR for the association between sexual harassment and depression. The aforementioned points mean that, although the results of this study may suggest there is a significant association between sexual harassment and symptoms of depression, there is a lack of strong evidence to support this and more research is needed.

Conclusions

Overall, this review provides a summary of the evidence on sexual harassment in LMICs. Despite a dramatic increase in the profile of sexual harassment over the past decade, there is limited definitional clarity and rigorously designed prevalence studies from LMICs that use validated measures for sexual harassment. Nevertheless, this review confirms that the prevalence of sexual harassment is high across workplace, educational and public settings and women experience a higher prevalence than men. Questions that capture behavioural acts over the direct query method appear more effective in garnering a response but this needs to be cognitively tested more widely. Our analysis also suggests that sexual harassment is associated with symptoms of depression. We, however, recognise the limitations of this pooled estimate and need higher quality studies that explore the consequences of sexual harassment in LMICs. As there is no sign that sexual harassment is abating, there is an urgent need to improve the measurement of sexual harassment and improved measures are particularly critical for large, repeat nationally representative surveys. Furthermore, with improved measures and a better understanding of the prevalence of this issue, by setting, policies and programmes can be designed accordingly.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Isabellepson

Contributors: Conceived and designed the study: MR, HS and JW. Data collection: MR. Analysed the data: MR, HS and IP. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: MR. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MR, HS, JW and IP. Agreed with manuscript results and conclusions: MR, HS, JW and IP.

Funding: The study received funding from the British Academy Sustainable Development Grant Programme (grant number SDP2\100069) and the European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant (IPV Tanzania 716458). Neither the British Academy nor the ERC did not contribute to study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data or writing the manuscript

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Not applicable as this is a systematic review and all the data are included in the manuscript and supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Littleton H, Abrahams N, Bergman M. Sexual assault, sexual abuse, and harassment: understanding the mental health impact and providing care for survivors; 2018. www.istss.org/sexual-assault [Accessed 04 Jun 2021].

- 3.Vuckovic M, Altvater A, Sekei LH. Sexual harassment and gender-based violence in Tanzania’s public service: A study among employees in Mtwara Region and Dar es Salaam. Int. J. Work. Heal. Manag 2017;10:116–33. 10.1108/IJWHM-02-2015-0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation . Violence against women – Intimate partner and sexual violence against women, Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Labour Office . Ending violence and harassment against women and men in the world of work, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morley L. Sex, grades and power in higher education in Ghana and Tanzania. Cambridge Journal of Education 2011;41:101–15. 10.1080/0305764X.2010.549453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merkin RS. The impact of sexual harassment on turnover intentions, absenteeism, and job satisfaction: findings from Argentina, Brazil and Chile. J. Int. Women’s Studies 2008;10:73–91 https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol10/iss2/7 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friborg MK, Hansen JV, Aldrich PT, et al. Workplace sexual harassment and depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis comparing harassment from clients or customers to harassment from other employees amongst 7603 Danish employees from 1041 organizations. BMC Public Health 2017;17:1–12. 10.1186/s12889-017-4669-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsh J, Patel S, Gelaye B, et al. Prevalence of workplace abuse and sexual harassment among female faculty and staff. J Occup Health 2009;51:314–22. 10.1539/joh.L8143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Labour Organization . Stop violence at work – International Woman’s Day, Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondestam F, Lundqvist M. Sexual harassment in higher education – a systematic review. Eur J High Educ 2020;0:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan DK-S, Chow SY, Lam CB, Chun BL, Yee Chow S, et al. Examining the Job-Related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Women Q 2008;32:362–76. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00451.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philpart M, Goshu M, Gelaye B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gender-based violence committed by male college students in Awassa, Ethiopia. Violence Vict 2009;24:122–36. 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedina L, Holmes JL, Backes BL. Campus sexual assault: a systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018;19:76–93. 10.1177/1524838016631129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilies R, Hauserman N, Schwochau S, et al. Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Pers Psychol 2003;56:607–31. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00752.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald LF, Gelfand MJ, Drasgow F. Measuring sexual harassment: theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic Appl Soc Psych 1995;17:425–45. 10.1207/s15324834basp1704_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das A. Sexual harassment at work in the United States. Arch Sex Behav 2009;38:909–21. 10.1007/s10508-008-9354-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organisation . Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector - questionnaire.Hum. Rights; 2003: 1–14.

- 19.Parish WL, Das A, Laumann EO. Sexual harassment of women in urban China. Arch Sex Behav 2006;35:411–25. 10.1007/s10508-006-9079-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank Group . World bank country and lending groups: country classification, 2021. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519

- 21.Adejuwon GA, Lawal AM. Perceived organisational target Selling, self-efficacy, sexual harassment and job insecurity as predictors of psychological wellbeing of bank employees in Nigeria. Ife Psychol 2013;21:17–29 https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ifep/article/view/91189 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaffer MA, Joplin JRW, Bell MP, et al. Gender discrimination and Job-Related outcomes: a cross-cultural comparison of working women in the United States and China. J Vocat Behav 2000;57:395–427. 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salman M, Abdullah F, Saleem A. Sexual harassment at workplace and its impact on employee turnover intentions. BER 2016;8:87–102. 10.22547/BER/8.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyefabi AOM, Yahuza BS. Ethical issues in knowledge, perceptions, and exposure to hospital hazards by patient relatives in a tertiary institution in North Western Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2016;19:622–31. 10.4103/1119-3077.188705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasti SA, Bergman ME, Glomb TM, et al. Test of the cross-cultural generalizability of a model of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology 2000;85:766–78. 10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L-N, Zong Q-Q, Zhang J-W, et al. Prevalence of sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Biol Sci 2019;15:749–56. 10.7150/ijbs.28144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu L, Dong M, Wang S-B, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against health-care professionals in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020;21:498–509. 10.1177/1524838018774429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu L, Dong M, Lok GKI, et al. Worldwide prevalence of sexual harassment towards nurses: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. J Adv Nurs 2020;76:980–90. 10.1111/jan.14296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan R and Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group . Cochrane consumers and communication review group: data synthesis and analysis, 2013. Cochrance Consumers and Communication. Available: http://cccrg.cochrane.org [Accessed 28 Sep 2020].

- 31.Akoku DA, Tihnje MA, Vukugah TA. Association between Male Customer Sexual Harassment and Depressive Symptoms among Female Bar Workers in Yaounde, Cameroon : A Cross-sectional Study. Am J Public Heal Res 2019;7:41–7. 10.12691/ajphr-7-2-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandes AC, Hayes RD, Patel V. Abuse and other correlates of common mental disorders in youth: a cross-sectional study in Goa, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:515–23. 10.1007/s00127-012-0614-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austrian K, Muthengi E. Can economic assets increase girls’ risk of sexual harassment? Evaluation results from a social, health and economic asset-building intervention for vulnerable adolescent girls in Uganda. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;47:168–75. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.08.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waubert de Puiseau B, Roessel J. Exploring sexual harassment and related attitudes in Beninese high schools: a field study. Psychology, Crime & Law 2013;19:707–26. 10.1080/1068316X.2013.793336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fineran S, Bennett L, Sacco T. Peer sexual harassment and peer violence among adolescents in Johannesburg and Chicago. Int Soc Work 2003;46:387–401. 10.1177/00208728030463009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mabetha K, De Wet N. Sexual harassment in South African schools: is there an association with risky sexual behaviours? S Afr J CH 2018;12:10–14. 10.7196/SAJCH.2018.v12i2b.1526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu H, Lyu Y, Ye Y. Workplace sexual harassment, workplace deviance, and family undermining. IJCHM 2019;31:594–614. 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fawole OI, Ajuwon AJ, Osungbade KO. Evaluation of interventions to prevent gender‐based violence among young female apprentices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Health Educ 2005;105:186–203. 10.1108/09654280510595254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koehlmoos TP, Uddin MJ, Ashraf A, et al. Homeless in Dhaka: violence, sexual harassment, and drug-abuse. J Health Popul Nutr 2009;27:452–61. 10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puri M, Cleland J. Assessing the factors associated with sexual harassment among young female migrant workers in Nepal. J Interpers Violence 2007;22:1363–81. 10.1177/0886260507305524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norman ID, Aikins M, Binka FN. Faith-Based organizations: sexual harassment and health in Accra-Tema Metropolis. Sex Cult 2013;17:100–12. 10.1007/s12119-012-9141-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park JB, Nakata A, Swanson NG, et al. Organizational factors associated with work-related sleep problems in a nationally representative sample of Korean workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2013;86:211–22. 10.1007/s00420-012-0759-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Wong WCW, Ip P, et al. A study of violence among Hong Kong young adults and associated substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and pregnancy. Violence Vict 2016;31:985–96. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo TY. Sexual harassment in the Chinese workplace. attitudes toward and experiences of sexual harassment among workers in Taiwan. Violence Against Women 1996;2:284–301. 10.1177/1077801296002003004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurya MK, Agarwal M. Relationship between perceived workplace harassment, mental health status and job satisfaction of male and female civil police Constables. Indian J Community Psychol 2014;10:162–77. 10.1177/2156869311416827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahraian A, Hemyari C, Ayatollahi SM, et al. Workplace violence against medical students in Shiraz, Iran. Shiraz E Med J 2016;17:e35754:4–5. 10.17795/semj35754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tripathi P, Tiwari R, Kamath R. Workplace violence and gender bias in Unorganized fisheries of Udupi, India. Int J Occup Environ Med 2016;7:181–5. 10.15171/ijoem.2016.788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dar LK, Hasan S. Traumatic experiences and dissociation in patients with conversion disorder. J Pak Med Assoc 2018;68:1776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aina AD, Kulshrestha P. Sexual Harassment in Educational Institutions in Delhi’ NCR (India): Level of Awareness, Perception and Experience. Sex Cult 2018;22:106–26. 10.1007/s12119-017-9455-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang CS, Yik MS, Cheung FM, et al. Sexual harassment of Chinese college students. Arch Sex Behav 1996;25:201–15. 10.1007/BF02437936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayekiso TV, Bhana K. Sexual harassment: perceptions and experiences of students at the University of Transkei. S Afr J Psychol 1997;27:230–5. 10.1177/008124639702700405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shumba A, Erinas A, Matina M. Sexual harassment of college students by Lecturers in Zimbabwe. Sex Education 2010;1811. 10.1080/14681810220133613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obozokhai O. Sexual harassment: the experience of out-of-school teenagers in Benin City, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2005;9:118–27. 10.2307/3583418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Owoaje ET, Olusola-Taiwo O. Sexual harassment experiences of female graduates of Nigerian tertiary institutions. Int Q Community Health Educ 2010;30:337–48. 10.2190/IQ.30.4.e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owoaje ET, Uchendu OC, Ige OK. Experiences of mistreatment among medical students in a university in South West Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2012;15:214–9. 10.4103/1119-3077.97321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dhlomo T, Mugweni RM, Shoniwa G, et al. Perceived sexual harassment among female students at a Zimbabwean institution of higher learning. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2012;22:269–72. 10.1080/14330237.2012.10820529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norman ID, Aikins M, Binka F. Traditional and Contrapower sexual harassment in public universities and professional training Institutes of Ghana. Int J Acad Res 2012;4:85–95 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293949498_TRADITIONAL_AND_CONTRAPOWER_SEXUAL_HARASSMENT_IN_PUBLIC_UNIVERSITIES_AND_PROFESSIONAL_TRAINING_INSTITUTES_OF_GHANA [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norman ID, Aikins M, Binka FN. Sexual harassment in public medical schools in Ghana. Ghana Med J 2013;47:128–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tobar S, Elsheshtawy E, Taha H. Harassment-related maladaptive cognitions in a sample of Mansoura university students, Egypt. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2015;22:171–7. 10.1097/01.XME.0000466277.08712.a6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Talboys SL, Kaur M, VanDerslice J, et al. What is Eve teasing? a mixed methods study of sexual harassment of young women in the rural Indian context. SAGE Open 2017;7:215824401769716. 10.1177/2158244017697168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murshid KAS, Murshid NS. Adolescent exposure to and attitudes toward violence: empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Child Youth Serv Rev 2019;98:85–95. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saberi HR, Motalebi Kashani M, Dehdashti A. Occupational violence among female workers in an Iranian industrial area. Women Health 2019;59:1075–87. 10.1080/03630242.2019.1593285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang Z, et al. Life and crisis: sexual harassment among Chinese college students. Int J Clin Exp Med 2019;12:4673–84 http://www.ijcem.com/files/ijcem0072606.pdfdoi:1940-5901/IJCEM0072606 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oni HT, Tshitangano TG, Akinsola HA. Sexual harassment and victimization of students: a case study of a higher education institution in South Africa. Afr Health Sci 2019;19:1478–85. 10.4314/ahs.v19i1.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Premadasa IG, Wanigasooriya NC, Thalib L, et al. Harassment of newly admitted undergraduates by senior students in a faculty of dentistry in Sri Lanka. Med Teach 2011;33:e556–63. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.600358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.pp. Hutagalung F, Ishak Z. Sexual harassment: a predictor to job satisfaction and work stress among women employees. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2012;65:723–30. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mamaru A, Getachew K, Mohammed Y. Prevalence of physical, verbal and nonverbal sexual harassments and their association with psychological distress among Jimma university female students: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Sci 2015;25:29–38. 10.4314/ejhs.v25i1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kunwar LB, Kunwar BB, Thapa P, et al. Sexual harassment in female at working place in Dhangadhi Municipality Kailali district of Nepal. Ind. Jour. of Publ. Health Rese. & Develop. 2015;6:18. 10.5958/0976-5506.2015.00190.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie Z, Li J, Chen Y, et al. The effects of patients initiated aggression on Chinese medical students’ career planning. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:1–8. 10.1186/s12913-017-2810-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tripathi K, Borrion H, Belur J. Sexual harassment of students on public transport: an exploratory study in Lucknow, India. Crime Prev Community Saf 2017;19:240–50. 10.1057/s41300-017-0029-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gautam N, Sapakota N, Shrestha S, et al. Sexual harassment in public transportation among female student in Kathmandu valley]]>. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2019;12:105–13. 10.2147/RMHP.S196230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tarekegn D, Berhanu B, Ali Y. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual violence among high school female students in Dilla town, Gedeo zone SNNPR, Ethiopia. Epidemiology 2017;07. 10.4172/2161-1165.1000320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dias T, Kociejowski A, Rathnayake S, et al. Sexual violence against women: a challenge. Ceylon Med J 2014;59:107–8. 10.4038/cmj.v59i3.7482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El Khoury C, et al. Sexual violence in childhood and Post-Childhood: the experiences of young men who have sex with men in Beirut. J Interpers Violence 2019:1–20. 10.1177/0886260519880164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gutek BA. How subjective is sexual harassment? an examination of Rater effects. Basic Appl Soc Psych 1995;17:447–67. 10.1207/s15324834basp1704_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haq IUL, Adeel M, Abbas A. Perceived abuse in undergraduate medical students of Lahore, Pakistan : a cross-sectional study. PJMHS 2018;12:1046–9 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329736064_Perceived_abuse_in_undergraduate_medical_students_of_Lahore_Pakistan_A_cross-sectional_study [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rotundo M, Nguyen DH, Sackett PR. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. J Appl Psychol 2001;86:914–22. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockdale MS, Vaux A, Cashin J. Acknowledging sexual harassment: a test of alternative models. Basic Appl Soc Psych 1995;17:469–96. 10.1207/s15324834basp1704_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Houle JN, Staff J, Mortimer JT, et al. The impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms during the early occupational career. Soc Ment Health 2011;1:89–105. 10.1177/2156869311416827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeSouza ER, Cerqueira E. From the kitchen to the bedroom: frequency rates and consequences of sexual harassment among female domestic workers in Brazil. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:1264–84. 10.1177/0886260508322189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lahsaeizadeh A, Yousefinejad E. Social Aspects of Women’s Experiences of Sexual Harassment in Public Places in Iran. Sex Cult 2012;16:17–37. 10.1007/s12119-011-9097-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haile RT, Kebeta ND, Kassie GM. Prevalence of sexual abuse of male high school students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:24. 10.1186/1472-698X-13-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berdahl JL, Moore C. Workplace harassment: double jeopardy for minority women. J Appl Psychol 2006;91:426–36. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murry WD, Sivasubramaniam N, Jacques PH. Supervisory support, social exchange relationships, and sexual harassment consequences: a test of competing models. Leadersh Q 2001;12:1–29. 10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00062-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stark S, Chernyshenko OS, Lancaster AR, et al. Toward standardized measurement of sexual harassment: shortening the SEQ-DoD using item response theory. Military Psychology 2002;14:49–72. 10.1207/S15327876MP1401_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bryant AL. Hostile Hallways: The AAUW Survey on Sexual Harassment in America’s Schools. J Sch Health 1993;63:355–7. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb07153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cleland J, Ingham R, Stone N. Asking young people about sexual and reproductive behaviours: WHO illustrative core instruments; 2001.

- 88.Rautio A, Sunnari V, Nuutinen M, et al. Mistreatment of university students most common during medical studies. BMC Med Educ 2005;5:1–12. 10.1186/1472-6920-5-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Braine JD, Bless C, Fox PMC. How do students perceive sexual harassment? an investigation on the University of natal, Pietermaritzburg campus. S Afr J Psychol 1995;25:140–9. 10.1177/008124639502500302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047473supp001.pdf (340.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Not applicable as this is a systematic review and all the data are included in the manuscript and supplementary information.