Abstract

Background

The phylogenetic relationships of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and Ephemeroptera (mayflies) remain unresolved. Different researchers have supported one of three hypotheses (Palaeoptera, Chiastomyaria or Metapterygota) based on data from different morphological characters and molecular markers, sometimes even re-assessing the same transcriptomes or mitochondrial genomes. The appropriate choice of outgroups and more taxon sampling is thought to eliminate artificial phylogenetic relationships and obtain an accurate phylogeny. Hence, in the current study, we sequenced 28 mt genomes from Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Plecoptera to further investigate phylogenetic relationships, the probability of each of the three hypotheses, and to examine mt gene arrangements in these species. We selected three different combinations of outgroups to analyze how outgroup choice affected the phylogenetic relationships of Odonata and Ephemeroptera.

Methods

Mitochondrial genomes from 28 species of mayflies, dragonflies, damselflies and stoneflies were sequenced. We used Bayesian inference (BI) and Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses for each dataset to reconstruct an accurate phylogeny of these winged insect orders. The effect of outgroup choice was assessed by separate analyses using three outgroups combinations: (a) four bristletails and three silverfish as outgroups, (b) five bristletails and three silverfish as outgroups, or (c) five diplurans as outgroups.

Results

Among these sequenced mitogenomes we found the gene arrangement IMQM in Heptageniidae (Ephemeroptera), and an inverted and translocated tRNA-Ile between the 12S RNA gene and the control region in Ephemerellidae (Ephemeroptera). The IMQM gene arrangement in Heptageniidae (Ephemeroptera) can be explained via the tandem-duplication and random loss model, and the transposition and inversion of tRNA-Ile genes in Ephemerellidae can be explained through the recombination and tandem duplication-random loss (TDRL) model. Our phylogenetic analysis strongly supported the Chiastomyaria hypothesis in three different outgroup combinations in BI analyses. The results also show that suitable outgroups are very important to determining phylogenetic relationships in the rapid evolution of insects especially among Ephemeroptera and Odonata. The mt genome is a suitable marker to investigate the phylogeny of inter-order and inter-family relationships of insects but outgroup choice is very important for deriving these relationships among winged insects. Hence, we must carefully choose the correct outgroup in order to discuss the relationships of Ephemeroptera and Odonata.

Keywords: Mitochondrial genome, Palaeoptera, Chiastomyaria, Metapterygota, Phylogeney, Gene rearrangement

Introduction

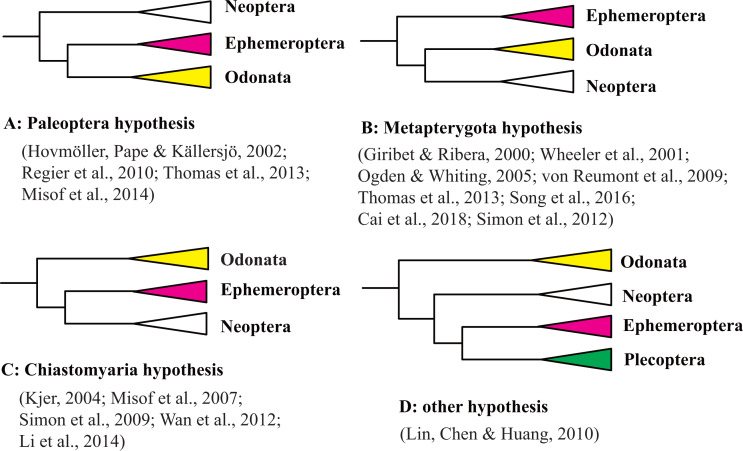

The origin of the winged insects is one of the most fascinating questions in the evolutionary biology of invertebrates. A current controversy is the phylogenetic relationship between the Ephemeroptera (mayfly) and Odonata (dragonfly and damselfly) that is hotly debated by taxonomists and systematists. Three main hypotheses have been proposed to explain the phylogenetic position of Ephemeroptera and Odonata based on morphological characteristics. The first hypothesis, termed the Palaeoptera hypothesis, suggests that Palaeoptera (=Ephemeroptera + Odonata) is the sister group of Neoptera based on characteristics including their inability to fold wings back over the abdomen, and the possession of an anal brace, bristle-like antennae, and intercalary veins that are exclusive to Palaeoptera (Bechly et al., 2001; Blanke et al., 2012; Hennig, 1981; Kukalová-Peck, 1991; Staniczek, 2000). The second hypothesis, termed the Metapterygota hypothesis (=Odonata + Neoptera), suggests that Ephemeroptera is the sister group to other winged insects based on the presence of a subimago, the caudal filament, absence of basalar-sternal muscles, and locking fixation of the anterior mandibular articulation (Grimaldi & Engel, 2005; Kristensen, 1981). The third hypothesis, termed the Chiastomyaria hypothesis (= Ephemeroptera + Neoptera), suggests that Odonata is the sister group to other winged insects due to a lack of direct sperm transfer among its species (Boudreaux, 1979; Matsuda, 1970). Molecular studies have provided support for each of three hypotheses even when using the same datasets. Results from different molecular datasets (e.g., mitochondrial genes, nuclear genes, mitochondrial genomes, transcriptomes, or whole genomes) are also not in consensus (Cai et al., 2018; Giribet & Ribera, 2000; Hovmöller, Pape & Källersjö, 2002; Kjer, 2004; Li, Qin & Zhou, 2014; Lin, Chen & Huang, 2010; Meusemann et al., 2010; Misof et al., 2007; Misof et al., 2014; Ogden & Whiting, 2003; Ogden & Whiting, 2005; Regier et al., 2010; Simon et al., 2009; Simon, Schierwater & Hadrys, 2010; Simon et al., 2012; Simon & Hadrys, 2013; Song et al., 2019; Wheeler et al., 2001; Zhang, Song & Zhou, 2008a; Zhang et al., 2010). Molecular studies in support of each of these three hypotheses are shown in Fig. 1 and Table S1, along with the outgroups and methods used in each study. In addition, some molecular datasets using similar gene datasets but different analysis methods support different hypotheses (Hovmöller, Pape & Källersjö, 2002; Meusemann et al., 2010; Hovmöller, Pape & Källersjö, 2002; Meusemann et al., 2010; Ogden & Whiting, 2003; Simon et al., 2009). Support for the Metapterygota hypothesis came from the use mitochondrial (mt) genomes (Zhang et al., 2008b; Cai et al., 2018). However, Zhang et al. (2010) and Lin, Chen & Huang (2010) suggested that Odonata was a sister to other Pterygota via analysis of mt genomes. Thomas et al. (2013) reanalyzed the dataset of Lin, Chen & Huang (2010) using the BEAST method and recovered Metapterygota, consistent with the original findings of Zhang et al. (2008b). Song et al. (2019) supported the Palaeoptera hypothesis using mt genomes. Whitfield & Kjer (2008) pointed out that an “ancient rapid radiation” was likely a major contributing factor to the unresolved relationship of winged insects using molecular datasets. However, only a few representatives from Odonata and Ephemeroptera were used in each of the previous phylogenetic studies of pterygotes (Misof et al., 2014; Regier et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2008b; Zhang et al., 2010). Most of these studies also examined relationships using different outgroup taxa even when using similar inference methods (Table S1). Rota-Stabelli & Telford (2008) have suggested that the choice of an appropriate outgroup is a fundamental prerequisite when the differences between two conflicting phylogenetic hypotheses depends on the position of the root. Hence, the question arises: if we increase taxon sampling and choose appropriate outgroups, can this give us enough information to obtain an accurate phylogeny?

Figure 1. Three hypothesis of the relationships among Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera.

(A) Paleoptera hypothesis; (B) Metapterygota hypothesis; (C) Chiastomyaria hypothesis; (D) other hypothesis.

The mt genome is a circular molecule of sizes ranging from approximately 15 to 20 kb and encodes 2 rRNA genes, 22 tRNA genes, 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), and an A+T-rich control region (Boore, 1999; Cameron, 2014). Phylogenetic analyses of insect mt genomes have indicated that mt PCGs are informative and useful sources of intra-order or lower level relationships (Cameron, 2014; Cameron & Whiting, 2008; Cheng et al., 2016; Kjer et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018). With the aim of reconstructing the phylogenetic relationships of primordial winged insect orders, we sequenced 28 complete or nearly complete mt genomes from Ephemeroptera (18 species), Odonata (eight species) and Plecoptera (two species). We also analyzed the mt gene arrangement characters and the phylogenetic relationships within Odonata and Ephemeroptera at the family-level.

Material and Methods

Ethical statement

No invertebrate specimens used in this study are protected under the provisions of the laws of People’s Republic of China on the protection of wildlife. Hence, there is no ethical problem with animal sampling. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Committee of Animal Research Ethics of Zhejiang Normal University.

Samples and sequencing

Mitochondrial genomes from 28 species of mayflies, dragonflies, damselflies and stoneflies were sequenced. All samples were collected between 2005 and 2014; information on species collected are available in Table 1. All mayflies and stoneflies were collected at the larval stage, whereas the dragonflies (or damselflies) were collected at the adult stage. All samples were preserved in 100% or 85% ethanol and stored at −40 °C in the Zhang‘s lab, College of Life Science and Chemistry, Zhejiang Normal University, China. All samples were identified by JY Zhang based on morphological characteristics. DNA was extracted from either a whole individual (for smaller species) or from the legs of an individual (for larger species) using DNeasy Tissue Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For each sample we amplified short 400–1,500 bp mt gene fragments using degenerate primers designed to match specific arthropod mt genes according to the method of Simon et al. (2006). PCR reaction conditions and procedures were as described in Zhang, Song & Zhou (2008a), Zhang et al. (2008b), Yu et al. (2016). Amplification parameters were not stringent (46−58 °C annealing temperatures). Short fragments were sequenced using the ABI 3730 system with bidirectional sequencing. Species-specific primers were then designed from these short fragments and used to amplify longer 2–3 kb segments of the mt genome from each sample. Long PCR products were sequenced directly using a primer-walking strategy initiated with specific primers with bidirectional sequencing. Raw sequence files were proofread manually and assembly of the nearly complete genome sequence was performed in SeqMan of Lasergene version 5.0 (Burland, 1999). Thirteen protein-coding genes (PCGs) and 2 rRNA (16S rRNA and 12S rRNA) genes were identified by comparisons with homologous sequences of known insect mt genes. Most tRNA genes were identified by their cloverleaf secondary structure using tRNAscan-SE 1.21 (Lowe & Eddy, 1997). If selected tRNA genes could not be determined by tRNAscan-SE, they were identified by comparison with the homologous insect tRNA genes.

Table 1. Information on specimen sources of the samples used in this study.

| Sample Number | Species | Order | Family | Location of collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TXF2014010 | Epeorus sp. | Ephemeroptera | Heptageniidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| FSJBF2010002 | Heptagenia sp. | Ephemeroptera | Heptageniidae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| FSJF2014001 | Iron sp. | Ephemeroptera | Heptageniidae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| AJXF2014001 | Cinygmina obliquistrita | Ephemeroptera | Heptageniidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| SXF2011004 | Ephemerellidae sp. | Ephemeroptera | Ephemerellidae | Sangzhi, Hubei |

| AYWF2014005 | Drunella sp. | Ephemeroptera | Ephemerellidae | Yuexi, Anhui |

| JSTF2010004 | Uracanthella sp. | Ephemeroptera | Ephemerellidae | Shangrao, Jiangxi |

| JXF2014002 | Serratella sp. | Ephemeroptera | Ephemerellidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| AHWF2014070 | Rhoenanthus sp. | Ephemeroptera | Potamanthidae | Huoshan, Anhui |

| HGHF2011011 | Potamanthus kwangsiensis | Ephemeroptera | Potamanthidae | Sangzhi, Hubei |

| AJDF2014110 | Isonychia ignota | Ephemeroptera | Isonychiidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| JSZF2010111 | Caenis sp. | Ephemeroptera | Caenidae | Shangrao, Jiangxi |

| JAXXCF2010090 | Leptophlebia sp. | Ephemeroptera | Leptophlebiidae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| JSMF2010046 | Ephemera shengmi | Ephemeroptera | Ephemeridae | Shangrao, Jiangxi |

| HBF2010057 | Ephemera sp. | Ephemeroptera | Ephemeridae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| AHYNF2014036 | Vietnamella sp. | Ephemeroptera | Austremerellidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| HHF2011069 | Ephoron yunnanensis | Ephemeroptera | Polymitarcyidae | Banna, Yunnan |

| NSF2005069 | Siphluriscus chinensis | Ephemeroptera | Siphluriscidae | Leishan, Guizhou |

| QTSC2010051 | Mnais sp. | Odonata | Calopterygidae | Lanxi, Zhejiang |

| SC2006001 | Platycnemis phyllopoda | Odonata | Platycnemididae | Nanjing, Jiangsu |

| HC2006051 | Ceriagrion nipponicum | Odonata | Coenagrionidae | Nanjing, Jiangsu |

| CT2006032 | Anisogomphus maacki | Odonata | Gomphidae; | Nanjing, Jiangsu |

| YDQ2012020 | Pseudothemis zonata | Odonata | Libellulidae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| ZFQ2012034 | Acisoma panorpoides | Odonata | Libellulidae | Zhoushan, Zhejiang |

| AJHQ2014065 | Pantala flavescens | Odonata | Libellulidae | Jinzhai, Anhui |

| DQ2010009 | Neallogaster pekinensis | Odonata | Cordulegastridae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| WQSJK2010108 | Perlidae sp. | Plecoptera | Perlidae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

| FSJCJ20100107 | Nemoura sp. | Plecoptera | Nemouridae | Jinhua, Zhejiang |

Taxa and alignment

In previous phylogenetic analyses some insect species have been reported to suffer from long-branch attraction and to have unstable phylogenetic positions (Nardi et al., 2003). Although many mt genomes from all orders of Insecta can now be acquired from GenBank data, we did not include data from those orders whose species showed long-branch attraction in previous phylogenetic analyses or high gene rearrangements or high base compositional biases which can cause erroneous results (Bergsten, 2005; Castro & Dowton, 2005; Ma et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2012). To reduce the computational analysis time we choose 1–5 species of the Diptera, Dermaptera, Lepidoptera, Orthoptera, Mantodea, Phasmida, Blattodea, Isoptera (=Blattodea: Termitoidae), Megaloptera, Neuroptera, Mecoptera, Grylloblattodea, Mantophasmatodea and Coleoptera as the ingroup. The outgroups selected were the four available bristletail sequences (Archaeognatha) ((Nesomachilis australica (Cameron et al., 2004), Pedetontus silvestrii (Zhang, Song & Zhou, 2008a), Petrobius brevistylis (Podsiadlowski, 2006), Trigoniophthalmus alternatus (Carapelli et al., 2007)) and three silverfishes (Thysanura) (Atelura formicaria (Comandi et al., 2009)), Tricholepidion gertschi (Nardi et al., 2003), Thermobia domestica (Cook, Yue & Akam, 2005)). We combined the 28 newly-sequenced mt genomes with 85 species from 19 orders of Insecta obtained from GenBank (Table 2). The ATP8 gene was not used in the subsequent analyses due to its shortness (about 50 amino acid residues) and its poor conservation (Zhang et al., 2008b). We aligned amino acid sequences of each mt protein-encoding gene separately. The dataset was composed of 113 taxa, including 4 bristletails, 3 springtails, 13 odonatans, 16 mayflies, 10 stoneflies and 39 neopteran species, all retrieved from GenBank (Table 2). We used two trivially different alignment methods (Cluster W and Muscle in Mega 7.0 (Kumar, Stecher & Tamura, 2016)). To reduce bias we deleted the nonconserved regions in each of gene alignment using GBlocks 0.91b (Castresana, 2000) with block parameters set as default. The two alignments and block identification procedures ensured that the conserved regions were reliably homologous. Each of the conserved alignments were concatenated for both nucleotide and amino acid translated datasets, a final alignment 7011 nucleotides and 2337 amino acids residues. A saturation analysis of the concatenated DNA was performed for first, second and third codon positions using DAMBE4.2.13 (Xia & Xie, 2001). Third codon positions were saturated so they were excluded from the final alignment and the final alignment 4674 including first and second codon positions of 113 sequences were obtained (named 113 dataset).

Table 2. GenBank numbers of the 113 taxa of insects in this study.

| Order | Species | Accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaeognatha | Pedetontus silvestrii | EU621793 | Zhang, Song & Zhou (2008a) |

| Petrobius brevistylis | AY956355 | Podsiadlowski (2006) | |

| Petrobiellus puerensis | KJ754503 | Ma et al. (2015) | |

| Trigoniophthalmus alternatus | EU016193 | Carapelli et al. (2007) | |

| Nesomachilis australica | AY793551 | Cameron et al. (2004) | |

| Zygentoma | Tricholepidion gertschi | AY191994 | Nardi et al. (2003) |

| Atelura formicaria | EU084035 | Comandi et al. (2009) | |

| Thermobia domestica | AY639935 | Cook, Yue & Akam (2005) | |

| Odonata | Ischnura pumilio | KC878732 | Lorenzo-Carballa (2014) |

| Platycnemis phyllopoda | MF352167 | this study | |

| Pseudolestes mirabilis | FJ606784 | unpublished | |

| Ceriagrion nipponicum | MF352157 | this study | |

| Euphaea formosa | HM126547 | Lin, Chen & Huang (2010) | |

| Euphaea ornate | KF718295 | unpublished | |

| Euphaea yayeyamana | KF718293 | unpublished | |

| Euphaea decorata | KF718294 | unpublished | |

| Mnais sp. | MF352166 | this study | |

| Vestalis melania | JX050224 | unpublished | |

| Atrocalopteryx atrata | KP233805 | unpublished | |

| Ictinogomphus sp. | KM244673 | Comandi et al. (2009) | |

| Davidius lunatus | EU591677 | Lee et al. (2009) | |

| Anisogomohus maacki | MF352151 | this study | |

| Pseudothemis zonata | MF352170 | this study | |

| Pantala flavescens | MF352148 | this study | |

| Acisoma panorpoides | MF352171 | this study | |

| Orthetrum triangulare | AB126005 | Yamauchi, Miya & Nishida (2004) | |

| Cordulia aenea | JX963627 | unpublished | |

| Hydrobasileus croceus | KM244659 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Neallogaster pekinensis | MF352152 | this study | |

| Ephemeroptera | Siphluriscus chinensis | HQ875717 | Li, Qin & Zhou (2014) |

| Siphluriscus chinensis | MF352165 | this study | |

| Ameletus sp. | KM244682 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Siphlonurus sp. | KM244684 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Parafronurus youi | EU349015 | Zhang, Song & Zhou (2008a) and Zhang et al. (2008b) | |

| Isonychia ignota | HM143892 | unpublished | |

| Epeorus sp.MT-2014 | KM244708 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Epeorus sp.JZ-2014 | KJ493406 | this study | |

| Isonychia ignota | MF352147 | this study | |

| Paegniodes cupulatus | HM004123 | unpublished | |

| Iron sp. | MF352155 | this study | |

| Heptagenia sp. | MF352153 | this study | |

| Cinygmina obliquistrita | MF352149 | this study | |

| Ephoron yunnanensis | MF352159 | this study | |

| Habrophlebiodes zijinensis | GU936203 | unpublished | |

| Ephemera orientalis | EU591678 | Lee et al. (2009) | |

| Ephemera sp. | MF352156 | this study | |

| Ephemera shengmi | MF352161 | this study | |

| Leptophlebia sp. | MF352160 | this study | |

| Siphlonurus immanis | FJ606783 | unpublished | |

| Potamanthus sp.MT-2014 | KM244674 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Rhoenanthus sp. | MF352145 | this study | |

| Potamanthus kwangsiensis | MF352158 | this study | |

| Caenis sp. QY-2009 | GQ502451 | unpublished | |

| Caenis sp. | MF352163 | this study | |

| Teloganodidae sp.MT-2014 | KM244703 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Ephemerella sp.MT-2014 | KM244691 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Drunella sp. | MF352150 | this study | |

| Vietnamella dabieshanensis | HM067837 | unpublished | |

| Vietnamella sp. | KM244655 | Tang et al. (2014) | |

| Vietnamella sp.JZ-2017 | MF352146 | this study | |

| Ephemerellidae sp. | MF352168 | this study | |

| Serratella sp. | MF352164 | this study | |

| Uracanthella sp. | MF352162 | this study | |

| Plecoptera | Acroneuria hainana | KM199685 | Huang et al. (2015) |

| Togoperla sp. | KM409708 | Wang, Liu & Yang (2014) | |

| Kamimuria wangi | KC894944 | unpublished | |

| Perlidae sp. | MF352169 | this study | |

| Dinocras cephalotes | KF484757 | Elbrecht et al. (2015) | |

| Apteroperla tikumana | KR604721 | Unpublished | |

| Nemoura sp. | MF352154 | this study | |

| Styloperla sp. | KR088971 | Chen, Wu & Du (2016) | |

| Pteronarcella badia | KU182360 | Sproul et al. (2015) | |

| Pteronarcys princeps | AY687866 | Stewart & Beckenbach (2006) | |

| Mesocapnia arizonensis | KP642637 | unpublished | |

| Cryptoperla sp.WX-2013 | KC952026 | Wu et al. (2014) | |

| Phasmatodea | Timema californicum | DQ241799 | Cameron, Barker & Whiting (2006) |

| Mantophasmatodea | Sclerophasma paresisensis | DQ241798 | Cameron, Barker & Whiting (2006) |

| Grylloblattodea | Grylloblatta sculleni | DQ241796 | Cameron, Barker & Whiting (2006) |

| Mantodea | Tamolanica tamolana | DQ241797 | Cameron, Barker & Whiting (2006) |

| Leptomantella albella | KJ463364 | Wang, Wang & Yang (2016) | |

| Blattodea | Blattella germanica | EU854321 | Xiao et al. (2012) |

| Periplaneta fuliginosa | AB126004 | Yamauchi, Miya & Nishida (2004) | |

| Eupolyphaga sinensis | FJ830540 | Zhang et al. (2010) | |

| Termitoidae | Coptotermes formosanus | KU925203 | Bourguignon et al. (2016) |

| Reticulitermes flavipes | EF206317 | Cameron & Whiting (2007) | |

| Diptera | Drosophila melanogaster | DMU37541 | Clary et al. (1982) |

| Chrysomya putoria | AF352790 | Junqueira et al. (2004) | |

| Simosyrphus grandicornis | DQ866050 | Cameron et al. (2007) | |

| Mecoptera | Neopanorpa pulchra | FJ169955 | unpublished |

| Raphidioptera | Mongoloraphidia harmandi | FJ859902 | Cameron et al. (2009) |

| Coleoptera | Pyrophorus divergens | EF398270 | Arnoldi et al. (2007) |

| Chaetosoma scaritides | EU877951 | Sheffield et al. (2008) | |

| Neuroptera | Ditaxis biseriata | FJ859906 | Cameron et al. (2009) |

| Polystoechotes punctatus | FJ171325 | Beckenbach & Stewart (2009) | |

| Megaloptera | Sialis hamata | FJ859905 | Cameron et al. (2009) |

| Corydalus cornutus | FJ171323 | Beckenbach & Stewart (2009) | |

| Protohermes concolorus | EU526394 | Hua et al. (2009) | |

| Orthoptera | Gastrimargus marmoratus | EU513373 | Ma et al. (2009) |

| Teleogryllus oceanicus | KT824636 | unpublished | |

| Teleogryllus emma | EU557269 | unpublished | |

| Velarifictorus hemelytrus | KU562918 | Yang, Ren & Huang (2016) | |

| Loxoblemmus equestris | KU562919 | Yang, Ren & Huang (2016) | |

| Locusta migratoria | X80245 | Flook, Rowell & Gellissen (1995) | |

| Trichoptera | Eubasilissa regina | KF756943 | Wang, Liu & Yang (2014) |

| Limnephilus decipiens | AB971912 | unpublished | |

| Lepidoptera | Saturnia boisduvalii | EF622227 | Hong et al. (2008) |

| Manduca sexta | EU286785 | Cameron & Whiting (2008) | |

| Bombyx mandarina | GU966631 | Li et al. (2010) | |

| Hemiptera | Triatoma dimidiata | AF301594 | Dotson & Beard (2001) |

| Homalodisca coagulata | AY875213 | unpublished | |

| Nezara viridula | EF208087 | Hua et al. (2008) | |

| Dermaptera | Euborellia arcanum | KX673196 | Song et al. (2016) |

| Labidura japonica | KX673201 | Song et al. (2016) | |

| Challia fletcheri | JN651407 | Wan et al. (2012) |

To compare the effect of outgroup choice, we added and analyzed two additional combinations of outgroup species: 114 dataset selecting five bristletails (Nesomachilis australica, Pedetontus silvestrii, Petrobius brevistylis, Trigoniophthalmus alternatus, and Petrobiellus puerensis) as outgroups according to the Metapterygota hypothesis supported by Cai et al. (2018); 119 dataset selecting five diplurans (Campodea lubbocki, C. fragilis, Japyx solifugus, Lepidocampa weberi, and Occasjapyx japonicus) as outgroups according to the Palaeoptera hypothesis supported by Song et al. (2019). The conserved region and saturation analyses are similar to the method used for the 113 dataset. The dataset with five bristletails as outgroups and the dataset with five diplurans as outgroups were named the 114 dataset and 119 dataset, respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses

PartitionFinder ver. 1.1.1 (Lanfear et al., 2012) was used to select partitions using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The 24 parts of three nucleotide datasets were divided into 9 partitions. The best model of three datasets was identified as a general time-reversible model (GTR+I+G) in all partitions excluding a TVM+I+ model in the second position of the COIII gene partition, whereas the second best model of this was the GTR+I+G using ModelGenerator v0.85 (Keane et al., 2006). To deduce differences in phylogenetic analyses we used a GTR+I+G model with first and second positions of 12 mt genes in three nucleotide datasets. We used MrBayes v. 3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012) to estimate phylogenies by Bayesian inference (BI) for each dataset. Two independent runs of four incrementally heated Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains (one cold chain and three hot chains) were simultaneously run for ten million generations depending on the datasets, with sampling conducted every 100 generations. The convergence of MCMC, which was monitored by the average standard deviation of split frequencies, reached below 0.01 within ten million generations depending on the dataset, and the initial 25% of the sampled trees were discarded as burn-in. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated from the remaining set of trees. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was conducted using PhyML (Guindon et al., 2005), specifying four substitution rate and the corresponding BI tree as the start tree. The confidence values of the ML tree were evaluated via a bootstrap test with 100 iterations.

Results

Genome organization of mtDNA

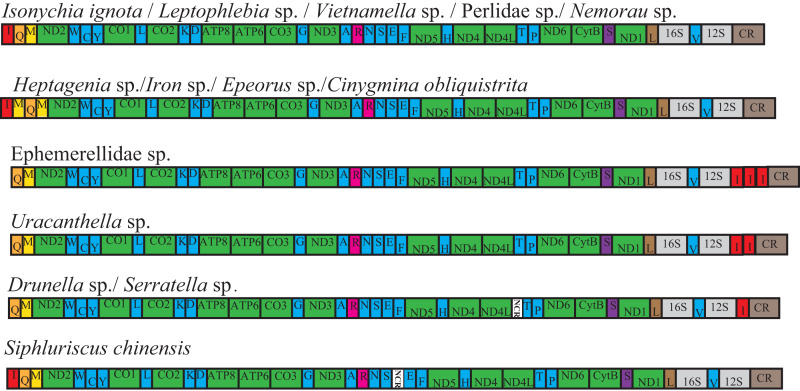

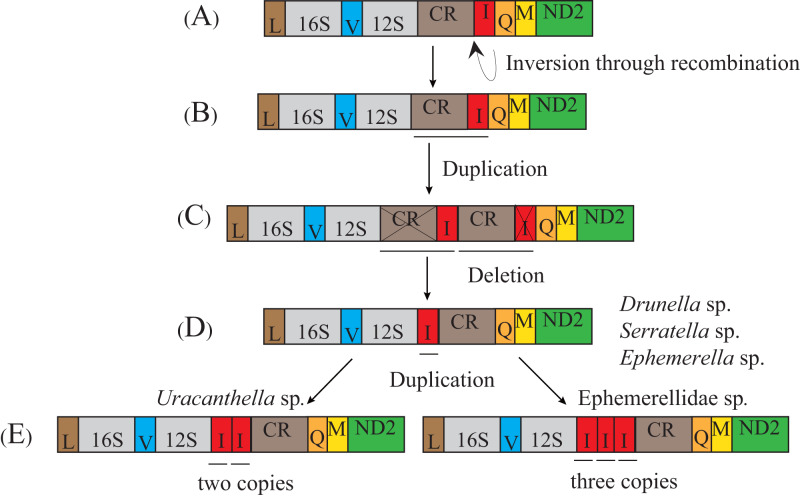

Of the 28 complete or nearly mt genomes of Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Plecoptera, four species of Ephemeroptera were found to contain a gene rearrangement, and four species of Ephemeroptera contained a tRNA gene duplication (Fig. 2). Four species from Heptageniidae (Cinygmina obliquistrita, Epeorus sp., Heptagenia sp. and Iron sp.) had an extra tRNA-Met gene located between tRNA-Ile and tRNA-Gln. Four species from Ephemerellidae (Drunella sp., Serratella sp., Uracanthella sp. and Ephemerellidae sp.) had a tRNA-Ile gene translocated and inversed to a position between 12S RNA and the control region. One copy of tRNA-Ile was present in Drunella sp. and Serratella sp., whereas two copies of this gene were present in Uracanthella sp. and three copies in Ephemerellidae sp.

Figure 2. Fourteen complete mitochondrial genome maps of the Ephemeroptera species used in this study.

The tRNAs are labeled according to the single-letter amino acid codes. The gene name above the median indicates the direction of transcription is from left to right, whereas the gene name below the median indicates right to left.

Phylogenetic analyses of three datasets

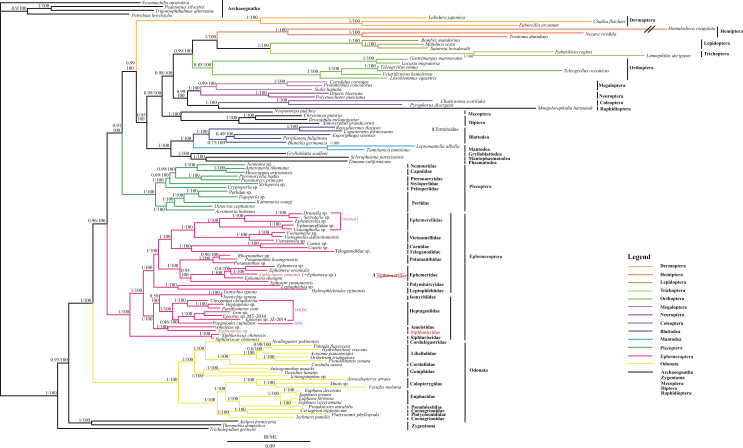

We employed BI and ML analyses to construct phylogenetic trees from three datasets with different outgroups (Fig. 3 and Figs. S1–S4). We found that different outgroups can affect the relationships between Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera. The Chiastomyaria hypothesis was strongly supported in BI analyses of three outgroup datasets and ML analysis of the 113 dataset (Fig. 3 and Figs. S1–S2), whereas different results in ML analyses of the 114 and 119 datasets were found (Figs. S3–S4). ML analyses in 114 and 119 datasets failed to support the Chiastomyaria hypothesis. No support for either the Palaeoptera or Metapterygota hypotheses was found in the BI and ML analyses in this study.

Figure 3. The BI and ML phylogenetic relationships of Ephemeroptera, Odonata and Neoptera as assessed from 12 protein-coding genes using nucleotide data 113FY7.

Phylogenetic analyses using nucleotide data were carried out for the 113 insect species based on all 12 protein-coding genes from their respective mt genomes. Four bristletails (Pedetontus silvestri, Petrobius brevistylis, Trigoniophthalmus alternatus, Nesomachilis australica) and three silverfishes (Atelura formicaria, Tricholepidion gertschi, Thermobia domestic) were used as outgroups. Numbers above the nodes are the posterior probabilities of BI and the bootstrap values of ML.

Comparing the phylogenetic trees derived from the three datasets with different outgroups, we found that the 113 dataset using 4 bristletails and 3 silverfishes as the outgroups is the stable phylogeny with high posterior probability and bootstrap value. In the 113 dataset, the monophyly of Odonata, Ephemeroptera and Neoptera was strongly supported in both BI and ML analyses (Fig. 3). Odonata as the sister of the remaining Pterygota had high posterior probability (1.00) and bootstrap value (100). Ephemeroptera as the sister of Neoptera also showed high support (BI/ML: 1.00/100) and Plecoptera was sister to the remaining other Neoptera with high support (0.92/100).

Within Odonata, the monophyly of the suborders Zygoptera and Anisoptera was well supported. At the family level, the monophyly of Gomphidae, Calopterygidae, Euphaeidae, and Libellulidae was well supported but the monophyly of Coenagrionidae was not supported since Platycnemididae clustered within Coenagrionidae.

Within Ephemeroptera, Siphluriscus chinensis (Siphluriscidae) was sister to the other mayflies, which were divided into two clades. All nodes had high posterior probabilities excluding (Heptageniidae + Isonychiidae) which was 0.59. The monophyly of all families excluding Siphlonuridae was well supported. The monophyly of Siphlonurus (Siphlonuridae) was not supported because Siphlonurus immanis (Siphlonuridae) (FJ606783) clustered within Ephemera (Ephemeridae) whereas Siphlonurus sp. (Siphlonuridae) was a sister clade to Ameletus sp. (Ameletidae).

Within Neoptera, the monophyly of Plecoptera, Mantodea, Blattodea (including Isoptera), Diptera, Coleoptera, Neuroptera, Megaloptera, Orthoptera, Trichoptera, Lepidoptera, Hemiptera, and Dermaptera were all supported. Polyneoptera was not monophyletic as Plecoptera was sister to the remaining Neoptera and in turn Dermaptera was sister to Neoptera except Plecoptera. Orthoptera failed to cluster with the other orders typically assigned to Polyneoptera and was sister to Amphiesmenoptera (Lepidoptera + Trichoptera). The relationship of (Plecoptera + (Dermaptera + other Neoptera)) was strongly supported. The other two datasets generated from the different outgroups in BI analyses (Figs. S1–S2) further supported the relationship of (Odonata + (Ephemeroptera + (Plecoptera + other orders of Neoptera)). All the topology of inter-order and intra-order in BI analyses of 114 and 119 datasets was coincident with the 113 dataset except posterior probabilities and branch length so we just showed the topology of intra-order level.

Discussion

The mtDNA rearrangement and rearrangement mechanisms

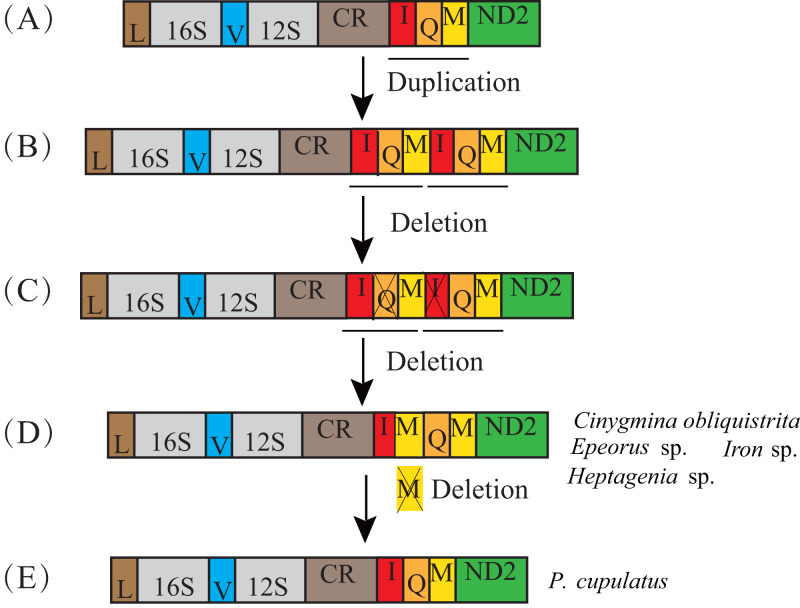

In the previously published mt genomes of Ephemeroptera, an extra tRNA-Met gene was found in the heptageniids, Parafronurus youi (Zhang et al., 2008b), Epeorus sp. (Tang et al., 2014), and Epeorus herklotsi (Gao et al., 2018), but was not found in Paegniodes cupulatus (Zhou et al., 2016). In the current study, Cinygmina obliquistrita, Epeorus sp., Heptagenia sp. and Iron sp. (Heptageniidae) all had the extra tRNA-Met. Based on the all species excluding P. cupulatus possessing an extra tRNA-Met (Fig. 3), we deduce that the common ancestor of the Heptageniidae had an extra tRNA-Met gene, which can be explained as well as P. youi through the tandem duplication-random loss (TDRL) model (Zhang et al., 2008b). However, the extra tRNA-Met gene in P. cupulatus was apparently deleted in an independent random loss thereby restoring the IQM tRNA gene cluster (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Proposed mechanism for the formation of an extra trnM gene in Heptageniidae under a tandem duplication and random loss model.

(A) Typical insect gene order. (B) Tandem duplication in the area of trnI-trnQ-trnM. (C) Subsequent deletions of trnQ between trnI and trnM, and trnI between trnM and trnQ. (D) trnI-trnM-trnQ-trnM cluster formed in Cinygmina obliquistrita, Epeorus sp., Iron sp. and Heptagenia sp. (E) Subsequent deletion of trnM between trnI and trnQ and trnI-trnQ-trnM formed again. The gene name above the median indicates the direction of transcription is from left to right, whereas the gene name below the median indicates right to left.

The transposition and inversion of tRNA-Ile genes in the mt genome of the Ephemerellidae can also be explained by the recombination and tandem duplication-random loss (TDRL) model (Fig. 5). Firstly, the tRNA-Ile inversion in Ephemerellidae may have been caused by a recombination in the original location, involving the breakage and rejoining of participating tRNA-Ile (Lunt & Hyman, 1997). Secondly, a tRNA-Ile inversion-CR arrangement probably occurred by duplication of the CR-tRNA-Ile inversion regions, resulting in a CR-tRNA-Ile inversion-CR-tRNA-Ile inversion arrangement, and then deleted by a subsequent random loss of the first copy CR and the second copy tRNA-Ile gene. At this point, it can be explained by a typical TDRL model (Moritz, Dowling & Brown, 1987). One copy of the tRNA-Ile gene inversion was formed in the ancestor of Drunella sp. and Serratella sp. as well as Ephemerella sp. (Ephemerellidae) (Tang et al., 2014), Cincticostella fusca (Ephemerellidae) (Li et al., 2020) and species of Serratella (Ephemerellidae) (Xu et al., 2020b), but three copies of the tRNA-Ile inversion in Ephemerellidae sp. as well as species of Torleya (Ephemerellidae) (Xu et al., 2020a; Xu et al., 2020b) and two copies of the tRNA-Ile in Uracanthella sp. were formed through different random duplications of the tRNA-Ile gene inversion.

Figure 5. Proposed mechanism of gene rearrangements of the trnI gene in Ephemerellidae under a model of tandem duplication of gene regions and recombination.

(A) Typical insect gene order. (B) Tandem duplication in the area from the control region (CR) to trnI. (C) Subsequent deletions of CR and trnI between CR and trnQ gene. (D) trnI gene inverted through recombination. (E) Tandem duplication of inverted trnI. The gene name above the median indicates the direction of transcription is from left to right, whereas the gene name below the median indicates right to left.

Phylogenetic analyses and the Chiastomyaria hypothesis

Each of the three hypotheses, Palaeoptera, Chiastomyaria or Metapterygota, have been supported in different studies using molecular datasets and various analysis methods (see Table S1). In our results, the use of increased numbers of mayfly, dragonfly, damselfly, and stonefly mt genomes sheds light on the phylogenetic origins of winged insects. Although outgroup choice may affect the phylogenetic relationships of Ephemeroptera and Odonata, we recovered support for the Chiastomyaria hypothesis with the choice of different outgroups. The hypothesis of Odonata as the origin of winged insects was also supported by Kjer (2004), Wan et al. (2012), Misof et al. (2014), Simon et al. (2012), Li, Qin & Zhou (2014). But some researchers supported the Metapterygota hypothesis using the mitochondrial genomes method (Tang et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2018; Zhang, Song & Zhou, 2008a; Zhang et al., 2008b).

Suitable outgroups are very important to determining phylogenetic relationships in the rapid evolution of insects. Hence, we must carefully choose the appropriate outgroups in order to discuss the relationships of Ephemeroptera and Odonata. According to the three outgroups tested in the current study, we propose that four bristletails and three silverfishes together is an ideal outgroup to use to evaluate the phylogenetic relationship of Ephemeroptera and Odonata. When we chose four bristletails and three silverfishes as the outgroups (113 dataset), the Chiastomyaria hypothesis was supported in ML and BI analyses (Fig. 3). When we chose five bristletails and three silverfishes as the outgroups (114 dataset), the Chiastomyaria hypothesis was only supported in BI analysis (Fig. S1), whereas the phylogenetic relationship of Ephemeroptera and Odonata failed to recover and formed an different relationship in PhyML analysis (Fig. S3). However, Cai et al. (2018) supported the Metapterygota hypothesis using the same outgroups (five bristletails and three silverfishes). When we used five diplurans as outgroups we also found strong support for the Chiastomyaria hypothesis in BI analysis (Fig. S2), whereas the phylogenetic relationship of Ephemeroptera and Odonata failed to recover in PhyML analysis (Fig. S4). Song et al. (2019) supported the Palaeoptera hypothesis using two species of Collembola and five species of Diplura as outgroups. We compared the outgroups used in published papers (Table S1) and found that few studies use the same outgroups. Thomas et al. (2013) thought that using few suitable outgroups or only distant outgroups may cause systematic error even in large datasets. Despite testing three outgroup combinations and finding support for Chiastomyaria hypothesis, the possibility still exists of bias in outgroup choice.

The phylogenetic family-level relationships in Odonata and Ephemeroptera

The phylogenetic relationships revealed among Odonata families in the current study are similar to the results of Yong et al. (2016) and Dijkstra et al. (2014). We demonstrated that the mt genome was a suitable marker to discuss the family-level phylogenetic relationships of Odonata, as also reported by Yong et al. (2016). However, the monophyly of Coenagrionidae was not supported in our study.

In the phylogenetic relationships at the family level, Siphluriscus chinensis (Siphluriscidae) was supported as sister to the rest of the Ephemeroptera as in the previous results of Ogden et al. (2009), Li, Qin & Zhou (2014), and Zhou & Peters (2003). Isonychiidae was a sister group to Heptageniidae, making the Suborder Setisura (=Heptagenioidea) as supported by McCafferty (1991), whereas Ogden & Whiting (2005), Ogden et al. (2009), Gao et al. (2018), Ye et al. (2018), Cao et al. (2020), and Xu et al. (2020a) supported Isonychiidae as sister to most Ephemeroptera (excluding Baetidae and Siphluriscidae).

The monophyly of Ephemerellidae with different copies of the tRNA-Ile inversion is well supported in this study. Our study identifies Ephemerella sp. as the sister group to the clade of Drunella sp. and Serratella sp. with one copy of the tRNA-Ile inversion. Ephemerellidae sp. with three copies of the tRNA-Ile inversion is the sister group to Uracanthella sp. with two copies. Ogden et al. (2009) found that Ephemerella and Serratella were not supported as monophyletic. In the present study we found a tRNA-Ile translocation and inversion in Ephemerellidae and a different copy of the tRNA-Ile inversion in Ephemerella and Serratella. This gives us more evidence to identify the monophyly of Ephemerella and Serratella in future studies. However, the mt genomes of Ephemeroptera are suitable markers to discuss the family-level phylogenetic relationship of Ephemeroptera.

The phylogenetic relationship of Plecoptera and Dermaptera

In previous studies of Neoptera, one Plecoptera (Pteronarcys princeps) and one Dermaptera (Challia fletcheri) species were included (Li, Qin & Zhou, 2014). Results indicated that P. princeps was sister to Orthoptera whereas Challia fletcheri with a very long-branch was sister to either the rest of Polyneoptera or Ephemeroptera. When only one species of Plecoptera (P. princeps) was included, but Dermaptera (C. fletcheri) was excluded (Lin, Chen & Huang, 2010; Zhang et al., 2010), Plecoptera was sister to Ephemeroptera. However, when we increased the sampling of Plecoptera and Dermaptera, we found that Plecoptera was sister to the remaining Neoptera, and Dermaptera was sister to Neoptera excluding Plecoptera. The position of Plecoptera as sister to the rest of Neoptera and not within Polyneoptera was very interesting. Although Beutel & Gorb (2006) proposed Plecoptera to be in this position, Cai et al. (2018) and Song et al. (2019) supported the position of Plecoptera as sister to the rest of Neoptera in the phylogenetic trees of BI and ML analyses. Some researchers also supported Plecoptera as likely occupying a position near the root of the Neoptera or Polyneoptera, and the aquatic life history stage to be an ancestral feature of winged insects (Marden & Kramer, 1994; Marden, 2013; Zwick, 2009). Most other studies placed Plecoptera within Polyneoptera, often as sister to Dermaptera (e.g., Kjer, 2004; Misof et al., 2007; Simon et al., 2012; Von Reumont et al., 2009). However, Matsumura et al. (2015) supported Plecoptera as the sister group to Zoraptera. Song et al. (2016) reported that Plecoptera was sister to Dermaptera but their ingroup data included only Polyneoptera (no Holometabola and Paraneoptera). Wipfler et al. (2019) found Plecoptera was sister to Polyneoptera excluding Zoraptera and Demaptera and suggested the ancestor of winged insects did not evolve in an aquatic environment. In our study, we recovered the relationship Odonata + (Ephemeroptera + (Plecoptera + (Dermaptera + other Neoptera))) with high posterior probabilities and bootstrap values (Fig. 3). So, our results suggest that the common ancestors of the winged insects and of Neoptera were aquatic, supporting the idea that wings did evolve in an aquatic environment.

The monophyly of Polyneoptera was not supported in this study because of the placement of Plecoptera, Dermaptera and Orthoptera. Although recent studies have supported the monophyly of Polyneoptera using mt genomes or transcriptome data (Song et al., 2016; Wipfler & Pass, 2014; Wipfler et al., 2019), we found most of studies included just the Polyneopteran orders. It is suggested that such analyses should always add more species representing all insect orders, not only Polyneoptera but also including Holometabola in order to discuss the monophyly of Polyneoptera. Our analysis of the 113 dataset indicated that Orthoptera was sister to Amphiesmenoptera (Lepidoptera + Trichoptera) which may be caused by long-branch attraction of Hemiptera (Fig. 3). However, we failed to support the monophyly of Orthoptera in BI analysis of the 119 dataset.

In conclusion, we found that the mt genome is a suitable marker to investigate the phylogenetic relationship of the inter-order and inter-family relationships of insects but that the outgroup choice is very important for deriving phylogenetic relationships among winged insects. We highly recommend that we should choose suitable species from Archaeognatha and Zygentoma together as the outgroups in future research and discussions of the phylogenies of Ephemeroptera and Odonata.

Supplemental Information

Phylogenetic analyses using nucleotide data were carried out for the 114 insect species based on all 12 protein-coding genes from their respective mt genomes. Five bristletails (Pedetontus silvestri, Petrobius brevistylis, Petrobiellus puerensis, Trigoniophthalmus alternatus, Nesomachilis australica) and three silverfishes (Atelura formicaria, Tricholepidion gertschi, Thermobia domestic) were used as outgroups. Numbers above the nodes are the posterior probabilities of BI. Subtrees of the monophyly of an Order were collapsed whereas the relationship within the Order is the same as Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analyses using nucleotide data were carried out for the 119 insect species based on all 12 protein-coding genes from their respective mt genomes. Five diplurans (Campodea lubbocki, C. fragilis, Japyx solifugus, Lepidocampa weberi, and Occasjapyx japonicus) were used as outgroups. Numbers above the nodes are the posterior probabilities of BI. Subtrees of the monophyly of the Order collapsed whereas the relationship within Order is the same as Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analyses using nucleotide data were carried out for the 114 insect species based on all 12 protein-coding genes from their respective mt genomes. Five bristletails (Pedetontus silvestri, Petrobius brevistylis, Petrobiellus puerensis, Trigoniophthalmus alternatus, Nesomachilis australica) and three silverfishes (Atelura formicaria, Tricholepidion gertschi, Thermobia domestic) were used as outgroups. Numbers above the nodes are the bootstrap values of ML. Subtrees of the monophyly of the Order collapsed whereas the relationship within the Order is the same as Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analyses using nucleotide data were carried out for the 119 insect species based on all 12 protein-coding genes from their respective mt genomes. Five diplurans (Campodea lubbocki, C. fragilis, Japyx solifugus, Lepidocampa weberi, and Occasjapyx japonicus) were used as outgroups. Numbers above the nodes are the bootstrap values of ML. Subtrees of the monophyly of the Order collapsed whereas the relationship within Order is the same as Fig. 3.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Peng Li for aid in taxon sampling. XY Gao thanks the National College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project from the National Department of Education for generous support to collect the samples (201810345046).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31370042 and 31000966), and by Zhejiang provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. LY18C040004). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

Kenneth B. Storey and Jia-Yong Zhang are Academic Editors for PeerJ.

Author Contributions

Dan-Na Yu, Pan-Pan Yu and Jia-Yong Zhang conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Le-Ping Zhang performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Kenneth B. Storey and Xin-Yan Gao performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The mitochondrial genomes are available at GenBank: MF352145–MF352171 and KJ493406MF.

References

- Arnoldi et al. (2007).Arnoldi F, Ogoh K, Ohmiya Y, Viviani V. Mitochondrial genome sequence of the Brazilian luminescent click beetle Pyrophorus divergens (Coleoptera: Elateridae): mitochondrial genes utility to investigate the evolutionary history of Coleoptera and its bioluminescence. Gene. 2007;405(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechly et al. (2001).Bechly G, Brauckmann C, Zessin W, Gröning E. New results concerning the morphology of the most ancient dragonflies (Insecta: Odonatoptera) from the Namurian of Hagen-Vorhalle (Germany) Journal of Zoological Systematics & Evolutionary Research. 2001;39:209–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0469.2001.00165.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckenbach & Stewart (2009).Beckenbach AT, Stewart JB. Insect mitochondrial genomics 3: the complete mitochondrial genome sequences of representatives from two neuropteroid orders: a dobsonfly (order Megaloptera) and a giant lacewing and an owlfly (order Neuroptera) Genome. 2009;52(1):31–38. doi: 10.1139/G08-098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten (2005).Bergsten J. A review of long-branch attraction. Cladistics. 2005;21:163–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2005.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel & Gorb (2006).Beutel RG, Gorb SN. A revised interpretation of the evolution of attachment structures in Hexapoda with special emphasis on Mantophasmatodea. Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny. 2006;64:3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.anrea.2015.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke et al. (2012).Blanke A, Wipfler B, Letsch H, Koch M, Beckmann F, Beutel R, Misof B. Revival of Palaeoptera—head characters support a monophyletic origin of Odonata and Ephemeroptera (Insecta) Cladistics. 2012;28:560–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boore (1999).Boore JL. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27:1767–1780. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux (1979).Boudreaux HB. Arthropod phylogeny, with special reference to insects. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon et al. (2016).Bourguignon T, Lo N, S˘obotník Sillam-Dussés, Roisin Y, Evans TA. Oceanic dispersal, vicariance and human introduction shaped the modern distribution of the termites Reticulitermes, Heterotermes and Coptotermes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2016:20160179. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burland (1999).Burland TG. DNASTAR’s Lasergene sequence analysis software. Bioinformatics Methods & Protocols. 1999;7:1–91. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai et al. (2018).Cai YY, Gao YJ, Zhang LP, Yu DN, Storey KB, Zhang JY. The mitochondrial genome of Caenis sp. (Ephemeroptera: Caenidae) and the phylogeny of Ephemeroptera in Pterygota. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:577–579. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1467239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron (2014).Cameron SL. Insect mitochondrial genomics: implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annual Review of Entomology. 2014;59:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Barker & Whiting (2006).Cameron SL, Barker SC, Whiting MF. Mitochondrial genomics and the new insect order Mantophasmatodea. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2006;38:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron et al. (2004).Cameron SL, Miller KB, D’Haese CA, Whiting MF, Barker SC. Mitochondrial genome data alone are not enough to unambiguously resolve the relationships of Entognatha, Insecta and Crustacea sensu lato (Arthropoda) Cladistics. 2004;20:534–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron et al. (2007).Cameron SL, Lambkin CL, Barker SC, Whiting MF. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Diptera: whole genome sequence data accurately resolve relationships over broad timescales with high precision. Systematic Entomology. 2007;32(1):40–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron et al. (2009).Cameron SL, Sullivan J, Song H, Miller KB, Whiting MF. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of the Neuropterida (lace-wings, alderflies and snakeflies) and their relationship to the other holometabolous insect orders. Zoologica Scripta. 2009;38(6):575–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2009.00392.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron & Whiting (2007).Cameron SL, Whiting MF. Mitochondrial genomic comparisons of the subterranean termites from the Genus Reticulitermes (Insecta: Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) Genome. 2007;50(2):188–202. doi: 10.1139/g06-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron & Whiting (2008).Cameron SL, Whiting MF. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within butterflies and moths. Gene. 2008;408:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao et al. (2020).Cao SS, Xu XD, Jia YY, Guan JY, Storey KB, Yu DN, Zhang JY. The complete mitochondrial genome of Choroterpides apiculata (Ephemeroptera: Leptophlebiidae) and its phylogenetic relationships. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020;5(2):1159–1160. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1730270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carapelli et al. (2007).Carapelli A, Liò P, Nardi F, Van der Wath E, Frati F. Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial protein coding genes confirms the reciprocal paraphyly of Hexapoda and Crustacea. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana (2000).Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro & Dowton (2005).Castro LR, Dowton M. The position of the Hymenoptera within the Holometabola as inferred from the mitochondrial genome of Perga condei (Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Pergidae) Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2005;34:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wu & Du (2016).Chen ZT, Wu HY, Du YZ. The nearly complete mitochondrial genome of a stonefly species, Styloperla sp. (Plecoptera: Styloperlidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27(4):2728–2729. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1046166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng et al. (2016).Cheng XF, Zhang LP, Yu DN, Storey KB, Zhang JY. The complete mitochondrial genomes of four cockroaches (Insecta: Blattodea) and phylogenetic analyses within cockroaches. Gene. 2016;586:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary et al. (1982).Clary DO, Goddard JM, Martin SC, Fauron CM, Wolstenholme DR. Drosophila mitochondrial DNA: a novel gene order. Nucleic Acids Research. 1982;10(21):6619–6637. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.21.6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comandi et al. (2009).Comandi S, Carapelli A, Podsiadlowski L, Nardi F, Frati F. The complete mitochondrial genome of Atelura formicaria (Hexapoda: Zygentoma) and the phylogenetic relationships of basal insects. Gene. 2009;439:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Yue & Akam (2005).Cook CE, Yue Q, Akam M. Mitochondrial genomes suggest that hexapods and crustaceans are mutually paraphyletic. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2005;272:1295–1304. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra et al. (2014).Dijkstra K-DB, Kalkman VJ, Dow RA, Stokvis FR, Van Tol J. Redefining the damselfly families: a comprehensive molecular phylogeny of Zygoptera (Odonata) Systematic Entomology. 2014;39:68–96. doi: 10.1111/syen.12035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson & Beard (2001).Dotson E, Beard C. Sequence and organization of the mitochondrial genome of the Chagas disease vector, Triatoma dimidiata. Insect Molecular Biology. 2001;10(3):205–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2001.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbrecht et al. (2015).Elbrecht V, Poettker L, John U, Leese F. The complete mitochondrial genome of the stonefly Dinocras cephalotes (Plecoptera, Perlidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26:469–470. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.830301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flook, Rowell & Gellissen (1995).Flook P, Rowell C, Gellissen G. The sequence, organization, and evolution of the Locusta migratoria mitochondrial genome. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1995;41(6):928–941. doi: 10.1007/BF00173173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao et al. (2018).Gao XY, Zhang SS, Zhang LP, Yu DN, Zhang JY, Cheng HY. The complete mitochondrial genome of Epeorus herklotsi (Ephemeroptera: Heptageniidae) and its phylogeny. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:303–304. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1445482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet & Ribera (2000).Giribet G, Ribera C. A review of arthropod phylogeny: new data based on ribosomal DNA sequences and direct character optimization. Cladistics. 2000;16:204–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi & Engel (2005).Grimaldi D, Engel MS. Evolution of the insects. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon et al. (2005).Guindon S, Lethiec F, Duroux P, Gascuel O. PHYML Online—a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33:W557–W559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig (1981).Hennig W. Insect phylogeny. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hong et al. (2008).Hong MY, Lee EM, Jo YH, Park HC, Kim SR, Hwang JS, Jin BR, Kang PD, Kim KG, Han YS. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the mitogenome of the silk moth Caligula boisduvalii (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) and comparison with other lepidopteran insects. Gene. 2008;413(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmöller, Pape & Källersjö (2002).Hovmöller R, Pape T, Källersjö M. The Palaeoptera problem: basal pterygote phylogeny inferred from 18S and 28S rDNA sequences. Cladistics. 2002;18:313–323. doi: 10.1006/clad.2002.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua et al. (2009).Hua J, Li M, Dong P, Xie Q, Bu W. The mitochondrial genome of Protohermes concolorus Yang et Yang 1988 (Insecta: Megaloptera: Corydalidae) Molecular Biological Reports. 2009;36(7):1757–1765. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. (2015).Huang M, Wang Y, Liu X, Li W, Kang Z, Wang K, Li X, Yang D. The complete mitochondrial genome and its remarkable secondary structure for a stonefly Acroneuria hainana Wu (Insecta: Plecoptera, Perlidae) Gene. 2015;557:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira et al. (2004).Junqueira ACM, Lessinger AC, Torres TT, da Silva FR, Vettore AL, Arruda P, Espin AMLA. The mitochondrial genome of the blowfly Chrysomya chloropyga (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Gene. 2004;339:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane et al. (2006).Keane TM, Creevey CJ, Pentony MM, Naughton TJ, Mclnerney JO. Assessment of methods for amino acid matrix selection and their use on empirical data shows that ad hoc assumptions for choice of matrix are not justified. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2006;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjer (2004).Kjer KM. Aligned 18S and insect phylogeny. Systematic Biology. 2004;53:506–514. doi: 10.1080/10635150490445922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjer et al. (2016).Kjer KM, Simon C, Yavorskaya M, Beutel RG. Progress, pitfalls and parallel universes: a history of insect phylogenetics. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2016;13:20160363. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen (1981).Kristensen NP. Phylogeny of insect orders. Annual Review of Entomology. 1981;26:135–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.26.010181.001031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kukalová-Peck (1991).Kukalová-Peck J. Fossil history and the evolution of hexapod structures. In: Naumann ID, Carne PB, Lawrence JF, Nielsen ES, Spradberry JP, Taylor RW, Whitten MJ, Littlejohn MJ, editors. The insects of Australia: a textbook for students and research Workers. CSIRQ Melbourne University Press; Melboure: 1991. pp. 141–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Stecher & Tamura (2016).Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear et al. (2012).Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SY, Guindon S. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2012;29:1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2009).Lee EM, Hong MY, Kim MI, Kim MJ, Park HC, Kim KY, Lee IH, Bae CH, Jin BR, Kim I. The complete mitogenome sequences of the palaeopteran insects Ephemera orientalis (Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae) and Davidius lunatus (Odonata: Gomphidae) Genome. 2009;52(9):810–817. doi: 10.1139/g09-055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2010).Li D, Guo Y, Shao H, Tellier LC, Wang J, Xiang Z, Xia Q. Genetic diversity, molecular phylogeny and selection evidence of the silkworm mitochondria implicated by complete resequencing of 41 genomes. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010;10(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qin & Zhou (2014).Li D, Qin JC, Zhou CF. The phylogeny of Ephemeroptera in Pterygota revealed by the mitochondrial genome of Siphluriscus chinensis (Hexapoda: Insecta) Gene. 2014;545:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2020).Li R, Zhang W, Ma ZX, Zhou CF. Novel gene rearrangement pattern in the mitochondrial genomes of Torleya mikhaili and Cincticostella fusca (Ephemeroptera: Ephemerellidae) International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;165:3106–3114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Chen & Huang (2010).Lin CP, Chen MY, Huang JP. The complete mitochondrial genome and phylogenomics of a damselfly, Euphaea formosa support a basal Odonata within the Pterygota. Gene. 2010;468:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Carballa (2014).Lorenzo-Carballa MO, Thompson DJ, Cordero-Rivera A, Watts PC. Next generation sequencing yields the complete mitochondrial genome of the scarce blue-tailed damselfly, Ischnura pumilio. Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(4):247–248. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.796518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe & Eddy (1997).Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt & Hyman (1997).Lunt DH, Hyman BC. Animal mitochondrial DNA recombination. Nature. 1997;387(247) doi: 10.1038/387247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma et al. (2009).Ma C, Liu C, Yang P, Kang L. The complete mitochondrial genomes of two band-winged grasshoppers, Gastrimargus marmoratus and Oedaleus asiaticus. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma et al. (2014).Ma C, Wang Y, Wu C, Kang L, Liu C. The compact mitochondrial genome of Zorotypus medoensis provides insights into phylogenetic position of Zoraptera. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma et al. (2015).Ma Y, He K, Yu PP, Yu DN, Cheng XF, Zhang JY. The complete mitochondrial genomes of three bristletails (Insecta: Archaeognatha): The paraphyly of Machilidae and insights into Archaeognathan phylogeny. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0117669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden (2013).Marden JH. Reanalysis and experimental evidence indicate that the earliest trace fossil of a winged insect was a surface-skimming neoptera. Evolution. 2013;67:274–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden & Kramer (1994).Marden JH, Kramer G. Surface-skimming stoneflies: a possible intermediate stage in insect flight evolution. Science. 1994;266:427–430. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5184.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda (1970).Matsuda R. Morphology and evolution of the insect thorax. Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada. 1970;102:5–431. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura et al. (2015).Matsumura Y, Wipfler B, Pohl H, Dallai R, Machida R, Câmara J. Cephalic anatomy of Zorotypus weidneri New, 1978: new evidence for a placement of Zoraptera. Arthropod Systematics Phylogeny. 2015;3:85–105. [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty (1991).McCafferty W. Toward a phylogenetic classification of the Ephemeroptera (Insecta): a commentary on systematics. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1991;84:343–360. doi: 10.1093/aesa/84.4.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meusemann et al. (2010).Meusemann K, von Reumont BM, Simon S, Roeding F, Strauss S, Kück P, Ebersberger I, Walzl M, Pass G, Breuers S. A phylogenomic approach to resolve the arthropod tree of life. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2010;27:2451–2464. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misof et al. (2014).Misof B, Liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C, Frandsen PB, Ware J, Flouri T, Beutel RG. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science. 2014;346:763–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1257570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misof et al. (2007).Misof B, Niehuis O, Bischoff I, Rickert A, Erpenbeck D, Staniczek A. Towards an 18S phylogeny of hexapods: accounting for group-specific character covariance in optimized mixed nucleotide/doublet models. Zoology. 2007;110:409–429. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, Dowling & Brown (1987).Moritz C, Dowling T, Brown W. Evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA: relevance for population biology and systematics. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1987;18:269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi et al. (2003).Nardi F, Spinsanti G, Boore JL, Carapelli A, Dallai R, Frati F. Hexapod origins: monophyletic or paraphyletic? Science. 2003;299:1887–1889. doi: 10.1126/science.1078607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden et al. (2009).Ogden TH, Gattolliat J, Sartori M, Staniczek A, Soldán T, Whiting M. Towards a new paradigm in mayfly phylogeny (Ephemeroptera): combined analysis of morphological and molecular data. Systematic Entomology. 2009;34:616–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2009.00488.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden & Whiting (2003).Ogden TH, Whiting MF. The problem with the Paleoptera problem: sense and sensitivity. Cladistics. 2003;19:432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden & Whiting (2005).Ogden TH, Whiting MF. Phylogeny of Ephemeroptera (mayflies) based on molecular evidence. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2005;37:625–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlowski (2006).Podsiadlowski L. The mitochondrial genome of the bristletail Petrobius brevistylis (Archaeognatha: Machilidae) Insect Molecular Biology. 2006;15:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier et al. (2010).Regier JC, Shultz JW, Zwick A, Hussey A, Ball B, Wetzer R, Martin JW, Cunningham CW. Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences. Nature. 2010;463:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature08742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist et al. (2012).Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van Der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota-Stabelli & Telford (2008).Rota-Stabelli O, Telford MJ. A multi criterion approach for the selection of optimal outgroups in phylogeny: recovering some support for Mandibulata over Myriochelata using mitogenomics. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2008;48:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield et al. (2008).Sheffield N, Song H, Cameron S, Whiting M. A comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes in Coleoptera (Arthropoda: Insecta) and genome descriptions of six new beetles. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2008;25(11):2499–2509. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon et al. (2006).Simon C, Buckley TR, Frati F, Stewart JB, Beckenbach AT. Incorporating molecular evolution into phylogenetic analysis, and a new compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers for animal mitochondrial DNA. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, & Systematics. 2006;37:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon & Hadrys (2013).Simon S, Hadrys H. A comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes among Hexapoda. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2013;69:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon et al. (2012).Simon S, Narechania A, DeSalle R, Hadrys H. Insect phylogenomics: exploring the source of incongruence using new transcriptomic data. Genome Biology & Evolution. 2012;4:1295–1309. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Schierwater & Hadrys (2010).Simon S, Schierwater B, Hadrys H. On the value of Elongation factor-1 α for reconstructing pterygote insect phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2010;54:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon et al. (2009).Simon S, Strauss S, Haeseler Avon, Hadrys H. A phylogenomic approach to resolve the basal pterygote divergence. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2009;26:2719–2730. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al. (2016).Song N, Li H, Song F, Cai W. Molecular phylogeny of Polyneoptera (Insecta) inferred from expanded mitogenomic data. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:36175. doi: 10.1038/srep36175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al. (2019).Song N, Li X, Yin M, Li X, Yin J, Pan P. The mitochondrial genomes of palaeopteran insects and insights into the early insect relationships. Scientific Reports. 2019;9:17765. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54391-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproul et al. (2015).Sproul JS, Houston DD, Nelson CR, Evans RP, Crandall KA, Shiozawa DK. Climate oscillations, glacial refugia, and dispersal ability: factors influencing the genetic structure of the least salmonfly, Pteronarcella badia (Plecoptera), in Western North America. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2015;15(1):279. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1046166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniczek (2000).Staniczek A. The mandible of silverfish (Insecta: Zygentoma) and mayflies (Ephemeroptera): its morphology and phylogenetic significance. Zoologischer Anzeiger. 2000;239:147–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00013.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart & Beckenbach (2006).Stewart JB, Beckenbach AT. Insect mitochondrial genomics 2: the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a giant stonefly, Pteronarcys princeps, asymmetric directional mutation bias, and conserved plecopteran A+ T-region elements. Genome. 2006;49(7):815–824. doi: 10.1139/g06-037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang et al. (2014).Tang M, Tan M, Meng G, Yang S, Su X, Liu S, Song W, Li Y, Wu Q, Zhang A. Multiplex sequencing of pooled mitochondrial genomes—a crucial step toward biodiversity analysis using mito-metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:e166. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas et al. (2013).Thomas JA, Trueman JW, Rambaut A, Welch JJ. Relaxed phylogenetics and the Palaeoptera problem: resolving deep ancestral splits in the insect phylogeny. Systematic Biology. 2013;62:285–297. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Reumont et al. (2009).Von Reumont BM, Meusemann K, Szucsich NU, Dell’Ampio E, Gowri-Shankar V, Bartel D, Simon S, Letsch HO, Stocsits RR, Luan YX. Can comprehensive background knowledge be incorporated into substitution models to improve phylogenetic analyses? A case study on major arthropod relationships. BMC ECvolutionary Biology. 2009;9:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan et al. (2012).Wan X, Kim MI, Kim MJ, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the free-living earwig, Challia fletcheri (Dermaptera: Pygidicranidae) and phylogeny of Polyneoptera. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e42056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2019).Wang J, Dai XY, Xu XD, Zhang ZY, Yu DN, Storey KB, Zhang JY. The complete mitochondrial genomes of five longicorn beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and phylogenetic relationships within Cerambycidae. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7633. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Liu & Yang (2014).Wang Y, Liu X, Yang D. The first mitochondrial genome for caddisfly (Insecta: Trichoptera) with phylogenetic implications. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2014;10(1):53–63. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Wang & Yang (2016).Wang K, Wang Y, Yang D. The complete mitochondrial genome of a stonefly species, Togoperla sp. (Plecoptera: Perlidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27(3):1703–1704. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.961130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler et al. (2001).Wheeler WC, Whiting M, Wheeler QD, Carpenter JM. The phylogeny of the extant hexapod orders. Cladistics. 2001;17:113–169. doi: 10.1006/clad.2000.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield & Kjer (2008).Whitfield JB, Kjer KM. Ancient rapid radiations of insects: challenges for phylogenetic analysis. Annual Review of Entomology. 2008;53:449–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipfler et al. (2019).Wipfler B, Letsch H, Frandsen PB, Kapli P, Mayer C, Bartel D, Buckley TR, Donath A, Edgerly-Rooks JS, Fujita M, Liu S, Machida R, Mashimo Y, Misof B, Niehuis O, Peters RS, Petersen M, Podsiadlowski L, Schütte K, Shimizu S, Uchifune T, Wilbrandt J, Yan E, Zhou X, Simon S. Evolutionary history of Polyneoptera and its implications for our understanding of early winged insects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of America. 2019;116:3024–3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817794116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipfler & Pass (2014).Wipfler B, Pass G. Antennal heart morphology supports relationship of Zoraptera with polyneopteran insects. Systematic Entomology. 2014;39:800–805. doi: 10.1111/syen.12088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2014).Wu HY, Ji XY, Yu WW, Du YZ. Complete mitochondrial genome of the stonefly Cryptoperla stilifera Sivec (Plecoptera: Peltoperlidae) and the phylogeny of Polyneopteran insects. Gene. 2014;537(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia & Xie (2001).Xia X, Xie Z. DAMBE: software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Journal of Heredity. 2001;92:371–373. doi: 10.1093/jhered/92.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao et al. (2012).Xiao B, Chen AH, Zhang YY, Jiang GF, Hu CC, Zhu CD. Complete mitochondrial genomes of two cockroaches, Blattella germanica and Periplaneta americana, and the phylogenetic position of termites. Current Genetics. 2012;58:65–77. doi: 10.1007/s00294-012-0365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu et al. (2020b).Xu XD, Jia YY, Cao SS, Zhang ZY, Storey KB, Yu DN, Zhang JY. Six complete mitochondrial genomes of mayflies from three genera of Ephemerellidae (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) with inversion and translocation of trnI rearrangement and their phylogenetic relationships. PeerJ. 2020b;8:e9740. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu et al. (2020a).Xu XD, Jia YY, Dai XY, Ma JL, Storey KB, Zhang JY, Yu DN. The mitochondrial genome of Caenis sp. (Ephemeroptera: Caenidae) from Fujian and the phylogeny of Caenidae within Ephemeroptera. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2020a;5(1):192–193. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1698986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, Miya & Nishida (2004).Yamauchi MM, Miya MU, Nishida M. Use of a PCR-based approach for sequencing whole mitochondrial genomes of insects: two examples (cockroach and dragonfly) based on the method developed for decapod crustaceans. Insect Molecular Biology. 2004;13(4):435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00505.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ren & Huang (2016).Yang J, Ren Q, Huang Y. Complete mitochondrial genomes of three crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) and comparative analyses within Ensifera mitogenomes. Zootaxa. 2016;4092(4):529–547. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4092.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye et al. (2018).Ye QM, Zhang SS, Cai YY, Storey KB, Yu DN, Zhang JY. The complete mitochondrial genome of Isonychia kiangsinensis (Ephemeroptera: Isonychiidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2018;3:541–542. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1467233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong et al. (2016).Yong HS, Song SL, Suana IW, Eamsobhana P, Lim PE. Complete mitochondrial genome of Orthetrum dragonflies and molecular phylogeny of Odonata. Biochemical Systematics & Ecology. 2016;69:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2016.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu et al. (2016).Yu P, Cheng X, Ma Y, Yu D, Zhang J. The complete mitochondrial genome of Brachythemis contaminata (Odonata: Libellulidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27:2272–2273. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.984176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Song & Zhou (2008a).Zhang JY, Song DX, Zhou KY. The complete mitochondrial genome of the bristletail Pedetontus silvestrii (Archaeognatha: Machilidae) and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within four bristletails. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 2008a;101:1131–1136. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746-101.6.1131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2008b).Zhang JY, Zhou C, Gai YH, Song DX, Zhou KY. The complete mitochondrial genome of Parafronurus youi (Insecta: Ephemeroptera) and phylogenetic position of the Ephemeroptera. Gene. 2008b;424:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2018).Zhang LP, Yu DN, Storey KB, Cheng HY, Zhang JY. Higher tRNA gene duplication in mitogenomes of praying mantises (Dictyoptera, Mantodea) and the phylogeny within Mantodea. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;111:787–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2010).Zhang YY, Xuan WJ, Zhao JL, Zhu CD, Jiang GF. The complete mitochondrial genome of the cockroach Eupolyphaga sinensis (Blattaria: Polyphagidae) and the phylogenetic relationships within the Dictyoptera. Molecular Biology Reports. 2010;37:3509–3516. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou & Peters (2003).Zhou CF, Peters JG. The nymph of Siphluriscus chinensis and additional imaginal description: a living mayfly with Jurassic origins (Siphluriscidae new family: Ephemeroptera) Florida Entomologist. 2003;86:345–352. [Google Scholar]