Abstract

Ependymoma is a malignant central nervous system tumor arising from the lining of the ventricles or central canal of the spinal cord. Extradural spinal ependymomas arise from heterotopic ependymal cells or the coccygeal medullary vestige and are extremely infrequent. We present a rare case of presacral extradural ependymoma. Extradural ependymomas typically demonstrate an extraneural spread and, thus, surveillance of the entire central nervous system is not typically recommended. A radiograph of the chest, liver profile, and attention to palpable lymphadenopathy (especially inguinal) on physical examination are vital for surveillance. Obtaining an R0 resection is the most important prognostic factor in survival and local recurrence.

Keywords: Myxopapillary ependymoma, Extradural spinal ependymoma, Presacral tumor

Ependymoma is a malignant central nervous system tumor arising from the lining of the ventricles or central canal of the spinal cord.1-3 Lumbosacral spinal ependymomas are rare tumors with approximately 227 intradural spinal ependymomas diagnosed annually in United States.1 Extradural spinal ependymomas arise from heterotopic ependymal cells or the coccygeal medullary vestige and are extremely infrequent, with only 75 cases in world literature since initial reference by Mallory in 1902.4-6 The primary method of treatment is surgical resection, though presacral extradural ependymomas have a local recurrence rate of approximately 60%, with associated 4-year mortality of 75%.4-6 Metastasis is typically extradural and most commonly involves the lungs, lymphatics, skeletal system, and liver. It carries a poor prognosis.1 We describe the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with a large, presacral, extradural myxopapillary ependymoma that was incidentally discovered during diagnostic work-up for a ureteral stone. Timely follow-up and surgical resection were necessary for both diagnostic and therapeutic intent. Subsequent pathological analysis confirmed our diagnosis of myxopapillary ependymoma, and it guided clinical decision making with respect to follow-up treatment and management.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy Hispanic male, aged 24-years, presented to the emergency department for evaluation of left flank pain. The patient had no history of fevers or chills, trauma, changes in bowel habits, weight loss, rectal bleeding, or proctalgia. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which showed a 3 mm proximal left ureteral stone (Figure 1a). Incidentally, a presacral mass with two lobulated components measuring 2.5 x 2.5 cm and 3.3 x 2.8 cm was also identified (Figure 1b). The patient was discharged home on pain medications and tamsulosin for nephrolithiasis and was referred to colorectal surgery for evaluation of presacral mass. Of note, the patient’s family history was significant for mother with a presacral teratoma.

Figure 1.

Non-contrasted CT showing (a) 3 mm stone in the left proximal ureter (red arrow) and (b) a lobulated rounded mass in the retrorectal space (green arrow).

Preoperative Evaluation

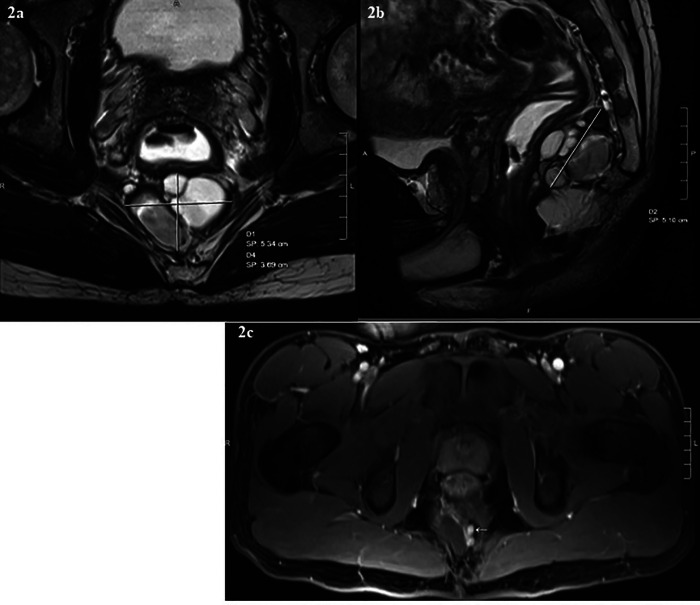

During consultation with colorectal surgery, a soft, posterior, midline mass was detected on digital rectal examination, with the highest margin 7–8 cm from the anal verge. Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a multiloculated cystic mass measuring 5.1 x 3.6 x 5.3 cm in the retrorectal space just anterior to the coccyx (Figures 2a & 2b). The mass was predominantly cystic, although there were some internal fat containing components that were T1 hyperintense and became hypointense on fat saturated images. Furthermore, there were some nodular areas of soft tissue enhancement, including along the superior margin that measured about 1.5 cm, and two other adjacent enhancing nodules inferiorly measuring about 5 mm each (Figure 2c). The mass was noted to be abutting the posterior wall of the distal rectum, which was slightly displaced by the cystic mass; however, no evidence of direct invasion or involvement of the rectum was visible, nor was there any adjacent bone destruction. Given the soft tissue nodularities and internal fat containing components, we favored a diagnosis of sacrococcygeal cyst, teratoma, or dermoid tumor.

Figure 2.

MR images showing a precoccygeal multiloculated cystic mass abutting the posterior wall of distal rectum. (a) Axial T2- weighted (b) Sagittal T2- weighted (c) T1- weighted axial images showing some small internal enhancing areas of soft tissue nodularity (arrow).

Operative Technique

Given there was no involvement of adjacent structures, the decision was made to proceed with surgical management. Presacral tumors can be resected via three common approaches: anterior transabdominal, posterior perineal, or combined abdominoperineal, which are dictated primarily by the location and peritumoral involvement of the adjacent bony structures or viscera.7 Because of the low-lying location of the tumor—below the level of S-3 vertebrae—we tackled this lesion via posterior paracoccygeal approach.

The patient was placed in a prone jack-knife position with buttocks taped apart (Figure 3a). A vertical intergluteal midline incision was made extending from the lower sacrum and coccyx to posterior anoderm. The anococcygeal raphe was divided. The levator ani and the gluteal attachments were dissected off the lateral aspects of the coccyx, and coccygectomy was subsequently performed gaining entry into the presacral space (Figure 3b). A bilobed, presacral, extradural mass was identified and excised en bloc, taking particular care to avoid rectal injury anteriorly by performing intermittent digital rectal examinations for guidance (Figure 3c). A drain was left in place, and the wound was closed in layers.

Figure 3.

(A) Positioning for posterior approach. (B) Coccygectomy. (C) Digital rectal examination to facilitate dissection. From Hassan I & Wietfeldt ED. Presacral tumors: diagnosis and management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(2):84-9311; used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.

Pathologic Evaluation

Gross pathologic analysis of the resected tumor demonstrated a bilobed cystic mass. The total mass measured 7.6 x 4.0 x 3.0 cm (Figure 4) and was made up of a 3 cm unilocular cyst filled with friable, tan, sebaceous material and lined by smooth tissue, with a second 2 cm cyst filled with clear, colorless, watery material and lined by smooth, glistening, membranous tissue.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative gross image of 7.6 x 4.0 x 3.0 cm bilobed mass resected in its entirety.

Microscopically, classic morphological features of subcutaneous myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE) characterized by cuboidal, columnar, and spindle cells arranged in a papillary manner around blood vessels were viewed (Figures 5a and 5b). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells demonstrated positive reaction to S100 protein (Figure 5c) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Figure 5d), suggesting the glial nature of the tumor.

Figure 5.

Subcutaneous myxopapillary ependymoma with GFAP, S-100 stain positive. EMA shows rare positivity. (a) Myxopapillary ependymoma has a distinctive appearance consisting of cuboidal, columnar and spindle cells with papillary arrangement around hyalinized blood vessels (black arrows). (b) Collagen balls identified within the tumor (blue arrows). (c) S100- positive stain. (d) GFAP positive stain.

Postoperative Surveillance

Approximately 4 months after resection of the ependymoma, the patient underwent a contrasted MRI of the pelvis that showed mild scarring without evidence of recurrent disease. A small 11 x 12 x 14 mm residual fluid collection was noted, which was thought to likely be a postoperative seroma. There was no nodular enhancing soft tissue or pelvic adenopathy, and the residual sacrum was noted to be unremarkable (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

T2-weighted MR images post interval resection of presacral ependymoma with small residual fluid collection likely a seroma. No obvious recurrent disease.

The patient was further evaluated by oncology. Baseline MRI of the spine demonstrated normal cervical, thoracic, and lumbar structures with no evidence of intradural mass. Due to relocation, the patient’s continued surveillance and care was transferred to an outside facility.

Discussion

Retrorectal or presacral tumors are uncommon and arise from any of the three germ cell layers in the presacral space.8 This space is bound anteriorly by the mesorectum, posteriorly by the anterior aspect of the sacrum, superiorly by the peritoneal reflection, and inferiorly by the recto-sacral fascia. Presacral tumors may be benign or malignant and are classified into congenital, neurogenic, osseous, and miscellaneous.9 Ependymomas are malignant neurogenic tumors,7 which are histologically divided into cellular or myxopapillary types.4,9 The cellular type usually occur in the cervical cord, and the myxopapillary occur almost exclusively in the conus medullaris and filum terminale.1,4,9 In the lumbosacral region, myxopapillary ependymomas can also occur extradurally in the sacrum, presacral space, or dorsal sacral subcutaneous tissue.5 Myxopapillary ependymomas tend to occur in young adults, with the greatest incidence in the fourth decade; they are slightly more common in males than females.1,9

The survival rated and local recurrence of spinal ependymomas are greatly influenced by the surgeon’s ability to achieve an R0 resection, which indicates a microscopically margin-negative resection, in which no gross or microscopic tumor remains in the primary tumor bed.1,3,8 Sonneland and colleagues8 noted a higher rate of recurrence is observed when resection is performed in a piecemeal fashion (19%) compared to en bloc resection (10%). In our case, we achieved total gross resection. Though adjuvant radiotherapy has been reported in cases of incomplete tumor resection, local recurrence or central nervous system metastases result from intradural ependymomas; the rarity of its extradural counterpart limits the amount of data available to assess the effectiveness of adjuvant radiotheraphy.1-3 Metastatic disease typically does not respond to radiotherapy or chemotherapy and is reported to have a grim 5-year survival.1

Unlike intradural ependymoma, extradural ependymoma has been reported to metastasize extraneurally, with prevalence ranging from 18% to 27%.5 The lung is the most common site of metastasis, with other reported sites including liver, skeletal system, and regional and distant lymph nodes.1 Thus, surveillance of extradural ependymoma is recommended, with particular attention to palpable lymphadenopathy (especially inguinal) on physical examination, radiography of the chest, and liver function test monitoring.1

Our patient had a presacral extradural myxopapillary ependymoma, a slow-growing tumor that generally presents with initial symptoms of pain, limb weakness, radiculopathy, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and/or abnormal gait due to mass effect on nerves and other organs.1,3,8 Our patient was asymptomatic, and his diagnosis was made incidentally on CT findings. Further cross sectional imaging with pelvic MRI accurately evaluated the extent of the tumor and ruled out involvement of adjacent structures. We did not biopsy the tumor prior to surgical resection due to concerns of tumor seeding at the biopsy site; however, post-surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis and guided clinical decision making with respect to treatment and monitoring.

The role of preoperative biopsy of presacral tumors is controversial. The argument in favor of a preoperative biopsy is determination of need for neoadjuvant therapy and surgical planning.1 Conversely, the concern for potential seeding of the biopsy tract or infecting the lesion needs to be considered.8 In a retrospective study assessing biopsy-related morbidity in solid presacral tumors, preoperative biopsy of presacral tumors was deemed safe with better concordance with postoperative pathology than with imaging alone.9 In a report from the Mayo Clinic, no seeding in the biopsy tract was reported.10 If a biopsy is obtained, it should be done within the field of planned resection (transperineal or parasacral). Transrectal and transvaginal biopsies are not recommended, though we consider post-surgical tumor analysis a necessary part of follow-up care for patients with extradural myxopapillary ependymomas.11

Conclusion

Myxopapillary extradural ependymomas are rare presacral tumors that tend to occur in young adults most frequently in their fourth decade of life. The tumor is more common in males than females. Unlike their intradural counterpart, extradural ependymomas do metastasize extraneurally. The lungs are the most common site of metastasis. Other reported sites of metastasis include liver, skeletal system, and regional and distant lymph nodes. Thus, oncological surveillance should include, at a minimum, chest radiographs, liver function monitoring, and a thorough physical examination assessing for lymphadenopathy. The prognosis of these patients is greatly influenced by the ability to achieve an R0 resection. Surgical approach to these tumors is based on the location in relation to the sacrum and peritumoral involvement of adjacent structures and viscera. The role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy has not been established in these patients. Assessing the effectiveness of these therapies is difficult due to lack of evidence.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Emily Andreae, PhD for editing assistance.

References

- 1.Fassett DR, Schmidt MH.. Lumbosacral ependymomas: a review of the management of intradural and extradural tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(5):E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh MC, Kim JM, Kaur G, et al. Prognosis by tumor location in adults with spinal ependymomas. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(3):226-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalid SI, Adogwa O, Kelly R, et al. Adult spinal ependymomas: an epidemiologic study. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e53-e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campen CJ, Fisher PG.. Ependymoma: an overview. In: Hayat MA, ed. Tumors of the central nervous system. 1st ed. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media; 2012. 269-277. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shors SM, Jones TA, Jhaveri MD, Huckman MS.. Best cases from the AFIP: myxopapillary ependymoma of the sacrum. Radiographics. 2006;26 Suppl 1:S111-S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao IS, Kapila K, Aggarwal S, Ray R, Gupta AK, Verma K.. Subcutaneous myxopapillary ependymoma presenting as a childhood sacrococcygeal tumor: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27(5):303-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merchea A, Dozois EJ.. Chapter 174: Retrorectal Tumor. In: Yeo CJ, ed. Shackelford’s surgery of the alimentary tract. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018. 2105–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonneland PR, Scheithauer BW, Onofrio BM.. Myxopapillary ependymoma. a clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985;56(4):883-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhlig BE, Johnson RL.. Presacral tumors and cysts in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18(7):581589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchea A, Larson DW, Hubner M, Wenger DE, Rose PS, Dozois EJ.. The value of preoperative biopsy in the management of solid presacral tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;5696):756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan I, Wietfeldt ED.. Presacral tumors: diagnosis and management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(2):84-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]