PURPOSE

Plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) sequencing is a compelling diagnostic tool in solid tumors and has been shown to have high positive predictive value. However, limited assay sensitivity means that negative plasma genotyping, or the absence of detection of mutation of interest, still requires reflex tumor biopsy.

METHODS

We analyzed two independent cohorts of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with known canonical driver and resistance mutations who underwent plasma cfDNA genotyping. We measured quantitative features, such as maximum allelic frequency (mAF), as clinically available measures of cfDNA tumor content, and studied their relationship with assay sensitivity.

RESULTS

In patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC harboring EGFR T790M, detection of driver mutation at > 1% AF conferred a sensitivity of 97% (368/380) for detection of T790M across three cfDNA genotyping platforms. Similarly, in a second cohort of patients with EGFR or KRAS driver mutations, when the mAF of nontarget mutations was > 1%, sensitivity for driver mutation detection was 100% (43/43). Combining the two NSCLC patient cohorts, the presence of nontarget mutations at mAF > 1% predicts for high sensitivity (> 95%) for identifying the presence of the known driver mutation, whereas mAF of ≤ 1% confers sensitivity of only 26%-54% across platforms. Focusing on 21 false-negative cases where the driver mutation was not detected on plasma next-generation sequencing, other mutations (presumably clonal hematopoiesis) were detected at ≤ 1% AF in 14 (67%).

CONCLUSION

Plasma cfDNA genotyping is highly sensitive when adequate tumor DNA content is present. The likelihood of a false-negative cfDNA genotyping result is low in a sample with evidence of > 1% tumor content. Bioinformatic approaches are needed to further optimize the assessment of cfDNA tumor content in plasma genotyping assays.

INTRODUCTION

Assays for genomic analysis of plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) are becoming increasingly integrated into diagnostic algorithms across solid tumors, and the appropriate use of plasma cfDNA testing as a complementary tool to tissue biopsy is an area of ongoing development. There are advantages to both cfDNA and tumor tissue biopsies in terms of convenience of testing, turnaround time, and amount of information gained. Biopsy of the primary tumor remains the gold standard for diagnosis and is necessary for morphologic and histologic characterization. Tissue biopsies also enable a more complete analysis of the spatial heterogeneity of the tumor, as well as the nature of the immune infiltrate and surrounding stroma that make up the tumor microenvironment. In addition, when larger core biopsies or surgical resection specimens are obtained, the amount of tissue available for pathologic analysis allows for more complete diagnostic testing in many cases.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Liquid biopsies positive for targetable mutations often affect treatment decisions in non–small-cell lung cancer, but negative tests are less informative because of variable assay sensitivity. This study explored whether mutation allele frequency (AF) can be used to assess the likelihood that a negative plasma genotyping test reflects a truly negative tumor versus low plasma tumor DNA content.

Knowledge Generated

When nontarget mutations are present in cell-free DNA at > 1% AF, sensitivity for detection of mutation of interest is > 95%. This is likely to be a liquid biopsy with adequate tumor content. Conversely, when nontarget mutations are present at ≤ 1%, sensitivity drops to approximately 50% or lower and it is more likely to be an uninformative test.

Relevance

In the context of adequate tumor content, negative liquid biopsy results may be more confidently interpreted as true negatives. Independent validation of these metrics is needed to develop robust clinical algorithms.

However, diagnostic tumor tissue biopsies can also frequently produce limited material and be inadequate for molecular analysis. Invasive tissue biopsies at diagnosis or treatment resistance can also sometimes be technically challenging, delayed by clinical status or logistical arrangements, or associated with significant morbidity. By contrast, plasma cfDNA genotyping is convenient and has been shown to have a high positive predictive value (PPV), making it a compelling option to support treatment selection both at initial diagnosis and after treatment resistance.1 This is especially true in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a disease entity in which there are several well-established oncogenic driver mutations associated with high rates of response to available targeted therapies.2,3

The most common targetable alterations in NSCLC are EGFR mutations.4-8 NSCLC harboring the common EGFR L858R and exon 19 deletion mutations (exon 19 del) has exhibited an overall survival benefit through first-line use of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) including osimertinib (including brain metastases) or dacomitinib (excluding brain metastases), whereas NSCLC with the first- and second-generation EGFR TKI resistance mutation EGFR T790M can be targeted in subsequent lines of therapy using the third-generation EGFR TKI osimertinib.8-11 It was thus appropriate that the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved assay for genotyping of plasma cfDNA was for noninvasive detection of EGFR mutations (Cobas EGFR Mutation Test v2). There are now a number of cfDNA genotyping assays (covering EGFR mutations and other targetable genotypes) commonly in clinical use. Each of these assays share a key limitation—while the specificity and PPV for actionable mutations is high such that detection of a targetable mutations is clinically actionable, sensitivity is imperfect, in the range of 60%-80% in patients with advanced NSCLC.12-14 This means that negative plasma genotyping requires a reflex to standard tumor genotyping; unfortunately, there often are clinical scenarios in which a biopsy for tumor genotyping may be risky to obtain or could incur significant delay to treatment. The risk of false-negative plasma cfDNA genotyping thus represents a clinical challenge. Clinicians are faced with the inability to confidently determine whether a negative plasma genotyping result is because of absence of target mutation in the tumor (a true negative) or because of a lack of adequate tumor DNA content in the liquid biopsy sample obtained (a false negative). We hypothesized there may be conditions under which the sensitivity of plasma genotyping can be determined to be high, decreasing the likelihood of false-negative results. In these settings, a negative result could be more reliable, reducing the utility of subsequent tumor genotyping, particularly if challenging or risky to obtain. In the studies outlined here, we investigated whether test parameters exist that can be clinically validated to predict whether a cfDNA genotyping sample contains, conceptually speaking, sufficient tumor DNA content to confidently rule out the presence of target mutations based on a negative plasma genotyping test.

METHODS

EGFR Resistance Cohort

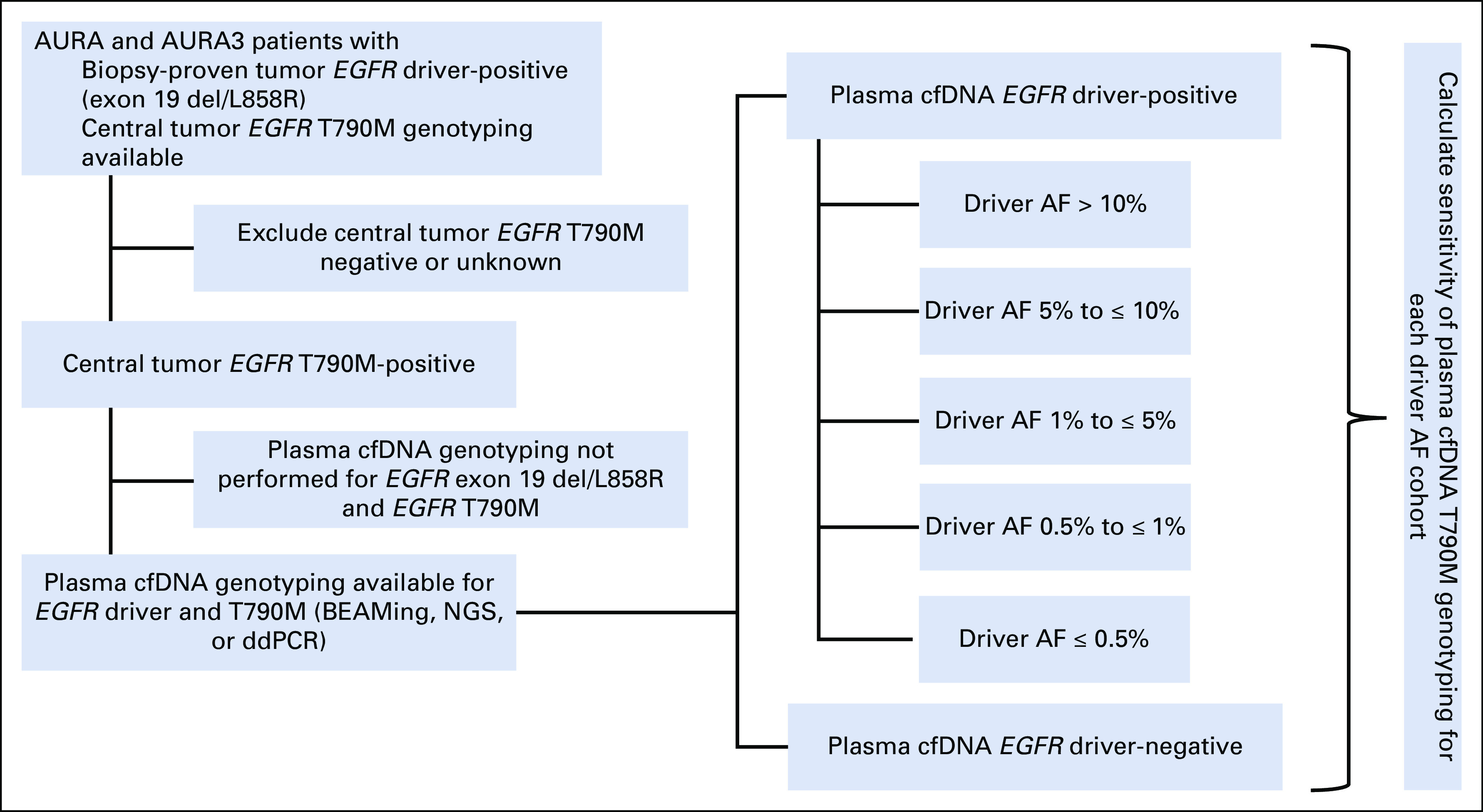

We first studied patients with NSCLC from the AURA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01802632) and AURA3 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02151981) trials, which enrolled patients with acquired resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs.8,9 Patients were eligible for this analysis if they were known to harbor both a common EGFR driver mutation (exon 19 del or L858R) as well as an EGFR T790M mutation on primary tumor genotyping and had also submitted plasma for cfDNA analysis (Fig 1; performed at screening concurrently with tissue biopsy, as per the trial protocol). In the AURA trial, plasma cfDNA genotyping was performed using the BEAMing digital polymerase chain reaction assay as described previously.13,15 In the AURA3 trial, plasma cfDNA genotyping was performed using a next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform (Guardant360; Guardant Health) and the Bio-Rad droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) technology (GeneStrat; Biodesix) as described previously.16-18 As a proxy for the plasma tumor content, we calculated the allele frequency (AF) of the known EGFR driver mutation. Plasma genotyping results were binned by EGFR driver AF, and sensitivity for detection of the known EGFR T790M mutation was calculated by dividing the number of cfDNA EGFR T790M-positives by the total of known tumor EGFR T790M-positives. All patients were consented for special analysis and treatment per protocol, and all tests performed on eligible patients were included in this analysis.

FIG 1.

Method of calculating EGFR T790M plasma cfDNA genotyping sensitivity stratified by EGFR driver allele frequency (AF). Schematic illustrating retrospective analysis of AURA/AURA3 plasma cfDNA genotyping data. Patients whose tumors were positive for both EGFR driver mutation (exon 19 del or L858R) and EGFR T790M and had plasma cfDNA genotyping data available for both EGFR driver and T790M were selected for analysis. The data set was then subdivided into cohorts based on EGFR driver AF, and sensitivity of plasma cfDNA T790M genotyping was calculated for each cohort, as compared to overall driver-positive and driver-negative cohorts (based on standard assay methodology). cfDNA, cell-free DNA; ddPCR, droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

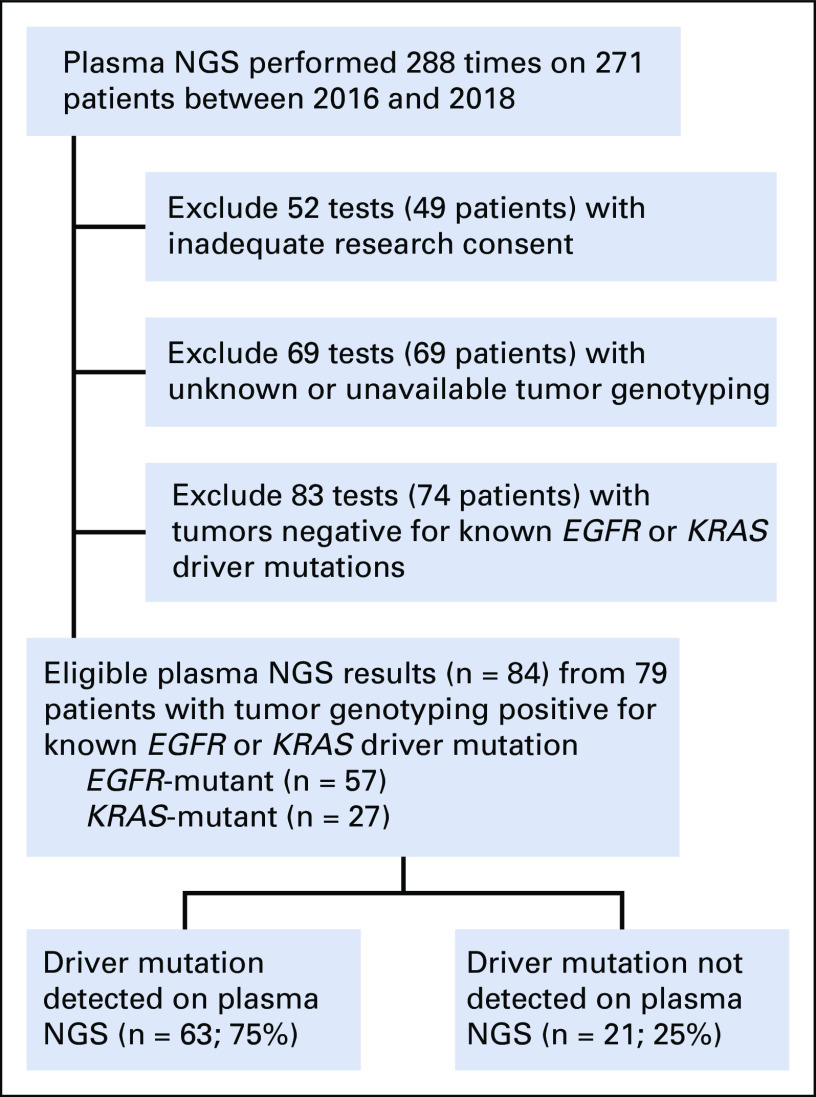

Institutional Plasma NGS Cohort

We then studied an institutional database of patients with NSCLC treated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute who underwent plasma cfDNA genotyping with a commercially available NGS assay (Guardant360; Guardant Health). Patients were eligible for this analysis if their tumor was known to harbor either an EGFR or KRAS driver mutation on tumor genotyping by institutional panel-based NGS19 and also underwent plasma NGS at any other timepoint in their care. As a proxy for the plasma tumor content, we calculated a variety of parameters from the plasma NGS results: mean/maximum mutation AF reported, total number of mutations reported detected, maximum copy-number value reported, and total number of copy-number alterations reported. When analyzing the mutations detected, we omitted the known tumor genotype of interest (driver mutations EGFR and KRAS) to avoid bias. Plasma genotyping results were binned by tumor content measures, and sensitivity for detection of the known EGFR or KRAS driver mutation was calculated by dividing the number of cfDNA EGFR and KRAS driver-positives by the total of known tumor EGFR and KRAS-positives, respectively. All patients were consented and treated with institutional review board approval. Five patients had testing done at two different clinical timepoints, and these were analyzed as separate results.

RESULTS

Sensitivity for Detection of EGFR T790M Resistance Mutation

A common application of cfDNA genotyping in patients with advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC is noninvasive detection of EGFR T790M or other resistance mutations after acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs. The large registrational trials of osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC resistant to early-generation EGFR TKIs collected plasma for development of cfDNA diagnostics and represent an opportunity for better understanding the performance of cfDNA genotyping. The phase I or II AURA and phase III AURA3 trials8,9 both enrolled patients at the time of acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs who had biopsy-proven tumor EGFR driver mutations, and both collected biopsy tissue at enrollment to test for the EGFR T790M resistance mutation.

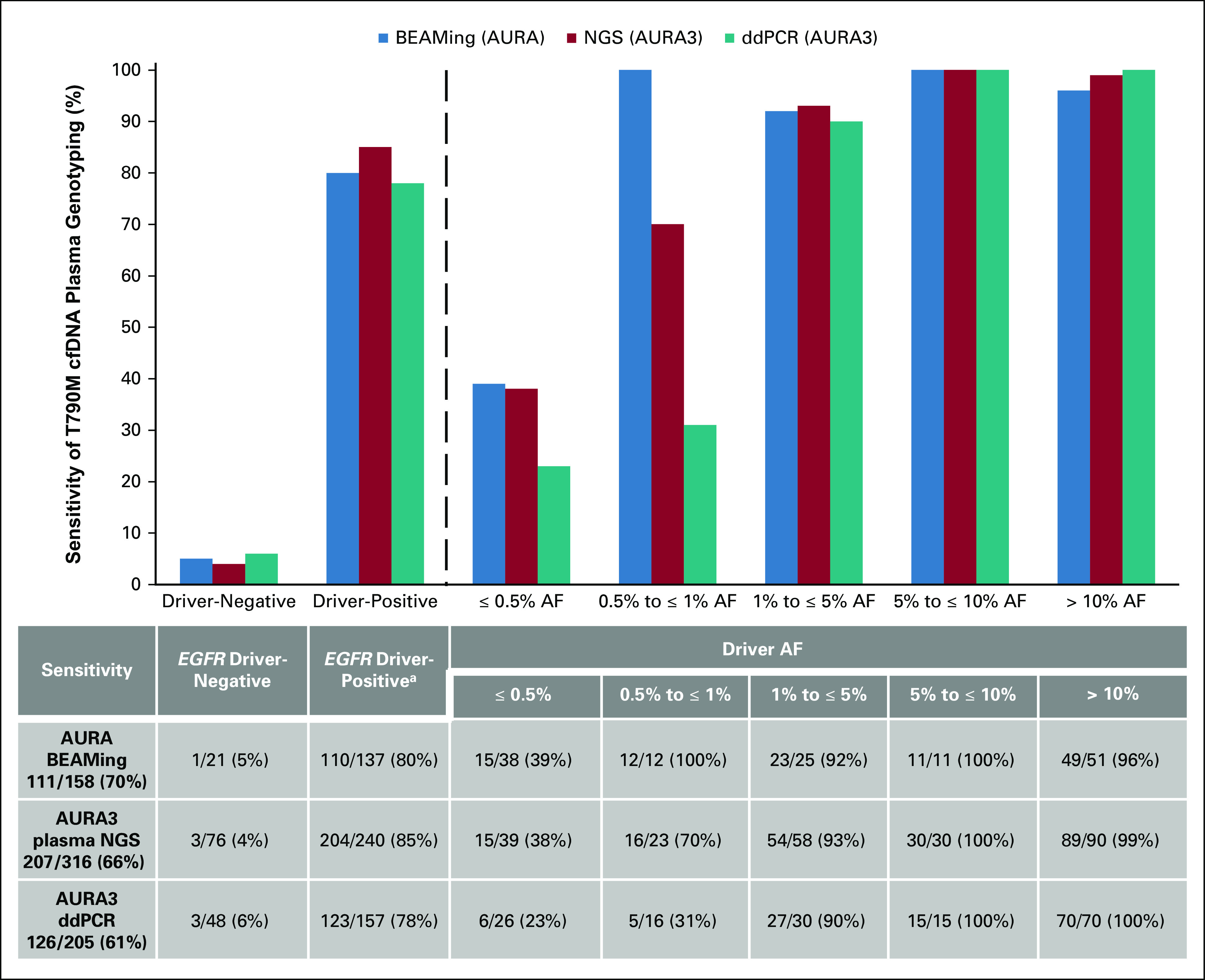

In addition to analysis of tumor tissue, plasma genotyping was performed for both the EGFR driver (exon 19 del/L858R) and T790M mutations (Fig 1). Plasma genotyping was performed with three different assays across the two trial cohorts: BEAMing (AURA), Guardant360 NGS (AURA3), and Biodesix ddPCR (AURA3). Of note, a portion of the patients included from the AURA3 trial underwent plasma genotyping with both the NGS and ddPCR platform, and the results from both assays are included in this analysis. The overall sensitivity for plasma detection of known EGFR T790M mutation present in the tumor biopsy ranged from 61% to 70% (BEAMing 111/158; NGS 207/316; ddPCR; 126/205). This is consistent with results of a previous analysis of the AURA trial data, which is a subset of the data used in this analysis.13 We then stratified samples according to the presence or absence of EGFR driver mutation detection in cfDNA, to determine whether detection of driver mutation can be used as a surrogate for adequacy of the plasma cfDNA sample. Among samples in which the known EGFR driver mutation was not detected in concurrent plasma cfDNA sequencing, the sensitivity for plasma T790M detection was expectedly low, ranging from 4%-6% (BEAMing 1/21; NGS 3/76; ddPCR 3/48; Fig 2). Conversely, when we combine all of the plasma genotyping samples in which EGFR driver mutations were detected (at any AF), the sensitivity for T790M detection was higher at 78%-85% (BEAMing 110/137; NGS 204/240; ddPCR 123/157; Fig 2). However, when we then further divide groups of patients by driver AF in a quantitative fashion, we find that, generally speaking, the sensitivity for T790M detection appears to increase as driver allele frequency increases, with highest sensitivity seen in cases with the highest evidence of tumor content (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Sensitivity for EGFR T790M is associated with allele frequency (AF) of the EGFR driver (exon 19 del or L858R). Sensitivity for T790M is predictably low when no EGFR driver mutation is detected. Furthermore, within cases where the EGFR driver mutations are detected, sensitivity improves with evidence of greater tumor content. Across all three platforms, sensitivity for T790M exceeds 95% when limited to cases where the EGFR driver mutation is seen at > 1% AF. aDriver positivity defined by performance characteristics of each individual assay and was predetermined by the assay supplier. cfDNA, cell-free DNA; ddPCR, droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

We then sought to define a threshold of driver mutation AF above which sensitivity for T790M detection is reliably high. We found that in cases where driver EGFR mutation is detected above 1% AF on plasma genotyping, sensitivity for plasma detection of T790M ranges from 95% to 97% (BEAMing 83/87; NGS 173/178; ddPCR 112/115). By contrast, when the EGFR driver mutation was detected ≤ 1% AF, sensitivity for T790M detection dropped to 26%-54% (BEAMing 27/50; NGS 31/62; ddPCR 11/42; Fig 2). Combining AURA and AURA3 data (BEAMing and NGS), the T790M false-negative rate was 52% (58/112) with detected driver AF ≤ 1% and only 3% (9/265) with an EGFR driver detected at AF > 1% (Fig 2).

Sensitivity for Detection of EGFR and KRAS Driver Mutations

We next studied an institutional cohort of patients with advanced NSCLCs harboring tumor biopsy-proven EGFR or KRAS driver mutations who underwent cfDNA analysis through plasma NGS testing (Fig 3). Similar to EGFR-mutant NSCLC, KRAS-mutant NSCLC represents a distinct, mutually exclusive molecular subtype of NSCLC for which detection of the KRAS driver oncogene, though not yet directly targetable, can help inform treatment.20 Based on the conceptual framework of our first cohort, we hypothesized that we could generate tumor content measures from the results of the plasma NGS assay that are associated with sensitivity of detection for mutations of interest. In this cohort, our mutations of interest were common EGFR and KRAS driver mutations. In an exploratory fashion, we studied a number of potential tumor content parameters and their value in distinguishing true positives (known EGFR or KRAS driver detected in plasma) from false negatives (known EGFR or KRAS driver not detected in plasma; Appendix Fig A1).

FIG 3.

Characteristics of institutional plasma NGS cohort. Patients with non–small-cell lung cancer known to have either an EGFR or KRAS driver mutation on tumor genotyping and also had plasma NGS results were selected for analysis. Five patients had testing done at two different clinical timepoints separated by a median of 4 months, and were analyzed as separate results. NGS, next-generation sequencing.

Given our finding that EGFR driver mutation AF was associated with sensitivity for detection of T790M in our first cohort, we hypothesized that AF of detected nontarget mutations on plasma NGS could again serve as a measure of tumor content and inform sensitivity for detection of the driver mutation. In these analyses, we studied allele frequency (mean and maximum) of all detected mutations excluding the mutation of interest (driver mutations EGFR and KRAS). We also tested several other quantitative outputs of the test as surrogate measures of tumor content, including total number of variants detected, quantity of copy-number alterations detected, and maximum copy-number value detected (Appendix Fig A1).

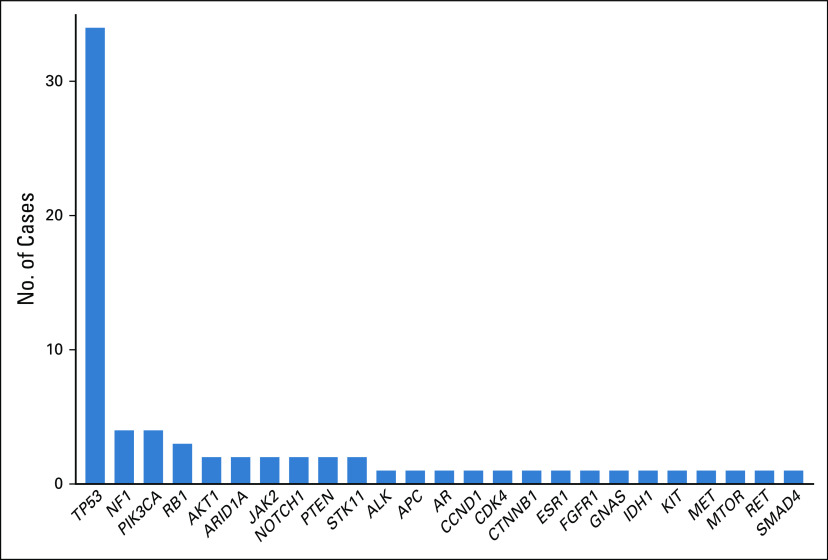

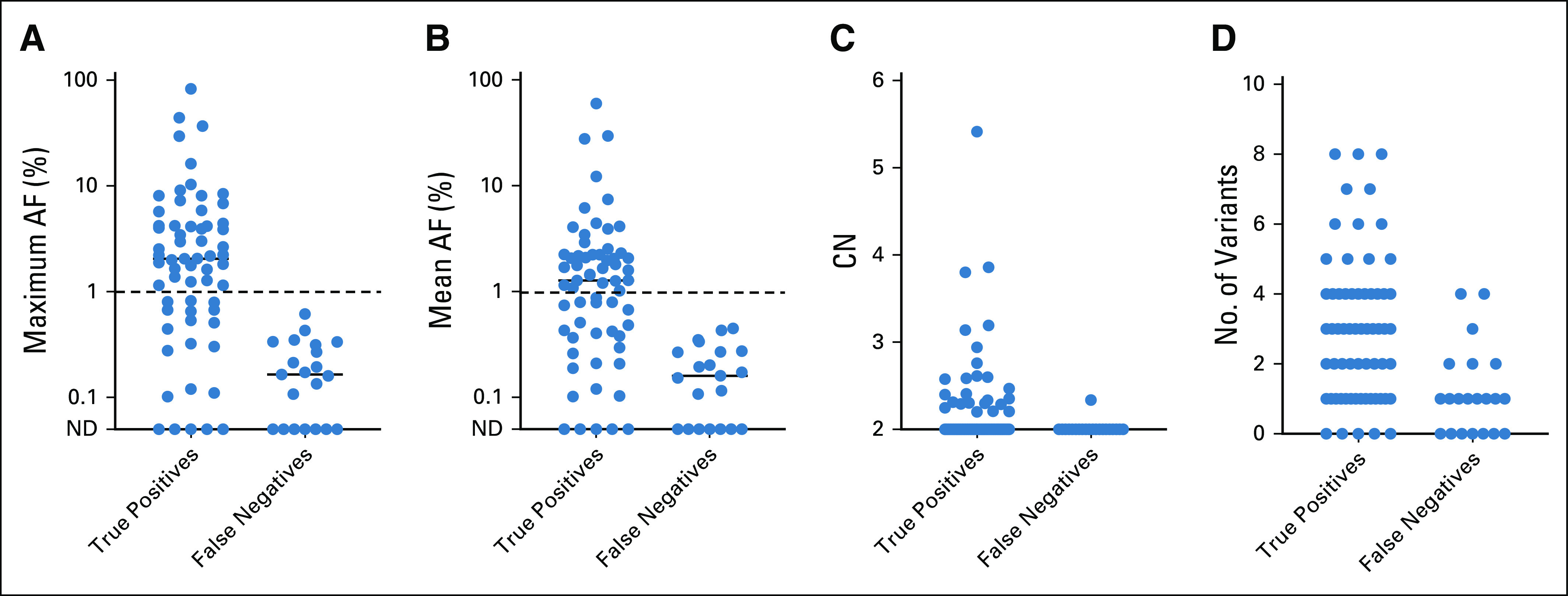

As compared to false-negative cases, true-positive cases had higher maximum allele frequency, higher mean allele frequency, higher number of total variants detected, higher number of copy-number alterations detected, and higher maximum copy-number value (Appendix Fig A1). For each of these parameters, a threshold could be drawn above which sensitivity for detection of the known EGFR or KRAS driver mutation was 100%. Comparing all of the tested parameters estimating tumor content, or liquid biopsy yield, the parameter for which the test achieved 100% sensitivity for detection of target mutation in the highest number of patients was maximum AF (Appendix Fig A1). There are a total of 72 cases for which maximum AF could be calculated, meaning there was at least one nondriver variant detected for which an AF value is reported. In 47% of cases (34/72), the variant with the maximum AF was a mutation in TP53, whereas in 53% of cases (38/72), it was a mutation in another gene (Appendix Fig A2).

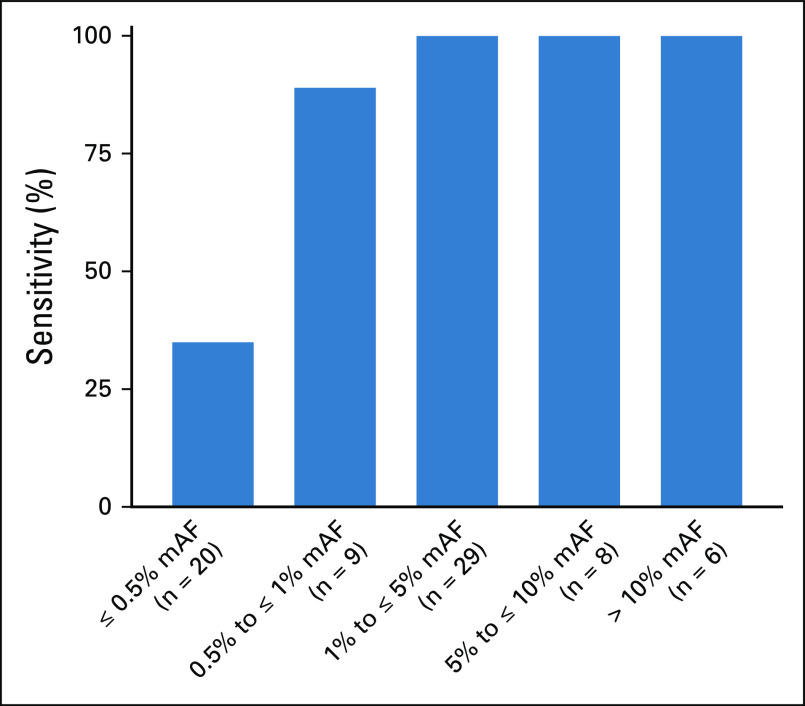

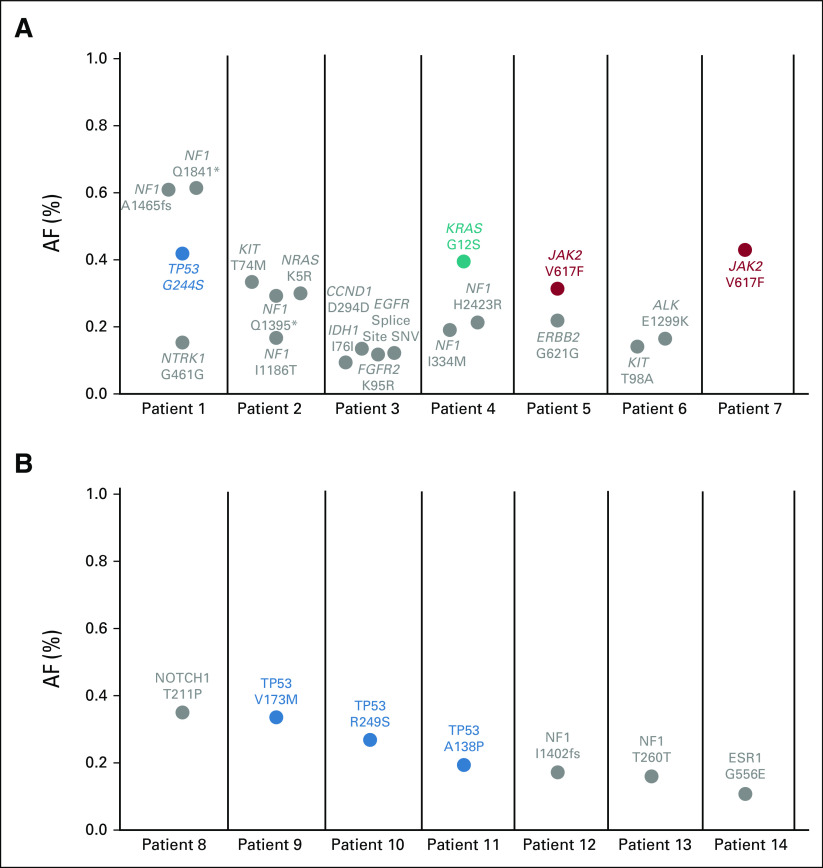

Similar to our EGFR resistance cohort, quantitative increase in the maximum AF (of any nontarget mutations detected) was associated with increased sensitivity for the EGFR or KRAS driver mutation of interest (Fig 4). In this assay, a maximum allele frequency of > 1% confers a sensitivity for detection of the mutation of interest of 100% (43/43). By contrast, when the maximum AF was ≤ 1% (or the sample lacked detection of any nontarget mutations), the sensitivity for the driver EGFR or KRAS mutation was 49% (20/41). Reviewing these false-negative cases, the lack of plasma detection of driver mutations known to be present in the tumor presumably represents a lack of tumor DNA shed into the plasma. However, it is notable that there are still variants detected in 67% (14/21) of these samples (Fig 5; Appendix Fig A1). These 21 false-negative cases reported a median of one mutation detected (range 0-4) and a median maximum AF of 0.19% (range 0%-0.61%). These mutations could be because of clonal hematopoiesis (CH), as we and others have previously reported.21,22

FIG 4.

Sensitivity of plasma next-generation sequencing for detection of EGFR and KRAS driver mutation increases with increased tumor content. The mAF of detected variants, excluding mutations in the driver gene of interest, was calculated across all variants detected in cell-free DNA. Of the 84 cases studied, mAF was not calculable for 12 cases as there were either no mutations detected or the only mutation detected was the driver EGFR or KRAS mutation, which was excluded from the analysis. In the remaining 72 cases, sensitivity for EGFR and KRAS driver mutations improved with greater mAF and was 100% in cases with mAF > 1%. mAF, maximum allele frequency.

FIG 5.

(A and B) Detection of mutations < 1% AF is common on plasma next-generation sequencing in the absence of apparent tumor content. Of the 21 false-negative cases where the driver mutation from tumor genotyping was not detected in cell-free DNA, in 14 (67%), at least one other variant was reported (range 1-4). Although some of these mutations are in genes known to be mutated in clonal hematopoiesis (in colors), many are nonrecurring or noncoding mutations in unexpected genes (green). AF, allele frequency; SNV, single-nucleotide variant.

DISCUSSION

Plasma cfDNA genotyping has become well established as a compelling diagnostic tool in solid tumor oncology, especially in settings where tumor histology is already known, tissue biopsy is clinically impractical, or tissue biopsy was performed but resulted in insufficient tissue for molecular analysis. However, the results of this type of testing can at times be challenging to interpret, as PPV for targetable genotypes is high, yet sensitivity is imperfect. This potential for false negatives means that the current standard of care after negative plasma genotyping is to reflex again to tumor tissue genotyping, potentially requiring a new biopsy. To address this clinical challenge, we focus here on developing a framework by which it may be possible to assess the likelihood that clinically relevant mutations are present in the tumor tissue but not detected in plasma sequencing. In developing this framework, we chose to focus on testing parameters that are practical to obtain and readily available to clinicians at the time of initial test results, such as allele frequency of detected variants.

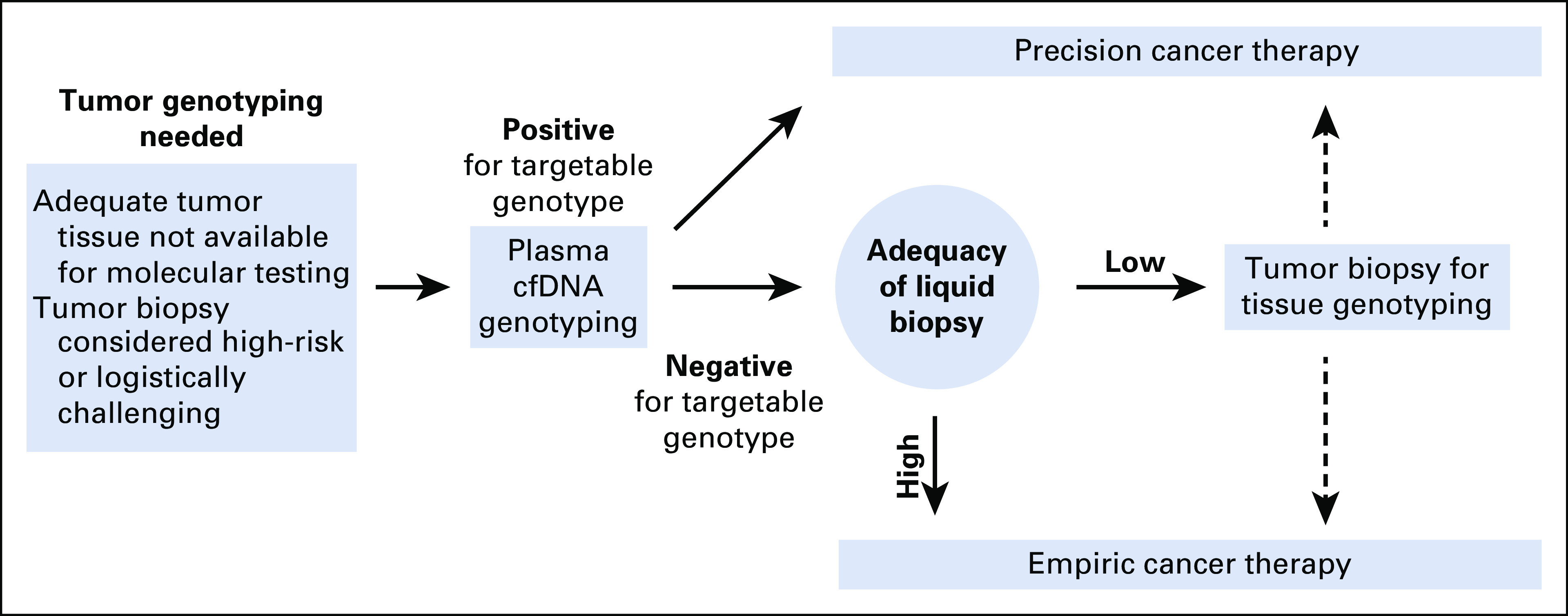

Based upon our retrospective analysis of multiple data sets, we propose an approach in which the adequacy of the liquid biopsy can be assessed. Our analysis finds that the sensitivity of cfDNA genotyping exceeds 95% when the maximum AF of detected mutations is high (> 1%), suggesting a lower likelihood of a false negative for a targetable mutation. Such information could be incorporated, along with clinical information, to make the most appropriate decision regarding the necessity of further diagnostic testing for the patient. Although reflex to tumor genotyping is routine, and often necessary for evaluation of histologic changes in the tumor, several factors might reduce enthusiasm for pursuing tumor genotyping. These include a low pretest probability for a targetable mutation (e.g. squamous histology and other clinical factors), potential morbidity of the biopsy, and the acuity of the patient's condition (Fig 6). We propose that the apparent adequacy of the plasma genotyping (ie, detection of a maximum AF > 1%) could also be used to gauge the likelihood of a false-negative result and inform the likely yield from further tumor genotyping. By contrast, detection of mutations below 1% AF does not necessarily indicate tumor content because the presence of mutations in a cfDNA sample does not ensure that these mutations are tumor-derived. In addition to the presence of germline mutations in cfDNA (which can be distinguished on the basis of AF and are often filtered out18), we and others have demonstrated that another source of cfDNA mutations is CH.21,22 CH mutations increase in prevalence with advancing age and occur in up to one third of older adults, making it especially important to consider their presence as false-positive results and discuss the potential role for concurrent sequencing of WBC DNA with cfDNA assessment.22,23 The majority of CH mutations in cfDNA have been seen at < 1% AF—whereas an EGFR mutation at < 1% AF would clearly represent a tumor driver (EGFR mutations are not seen in CH), a TP53 mutation at < 1% AF could be tumor-derived or could be evidence of CH.18

FIG 6.

Using liquid biopsy adequacy assessment to aid decision making regarding subsequent tumor biopsy for tissue genotyping. Although positive liquid biopsy results can be considered actionable, negative results reflex to tumor biopsy for genotyping, given the imperfect sensitivity of plasma genotyping. Tumor biopsies can be logistically challenging; thus, several factors such as patient acuity, risk of the procedure, and pretest probability of finding an actionable mutation affect the decision to proceed with biopsy. We propose that liquid biopsy adequacy assessment could be used to better understand the sensitivity of the liquid biopsy that was performed and the likelihood of a missed result. If, for example, plasma genotyping is negative for the mutation of interest and the sample is deemed to be inadequate (eg, maximum allele frequency on plasma next-generation sequencing is below 1%), this suggests low sensitivity and potentially greater yield from a biopsy for tumor genotyping. cfDNA, cell-free DNA.

There are clear limitations to our analysis, motivating further study on this topic. First, this analysis was post-hoc and deserves independent prospective validation. Second, our analysis is based on the fact that tumor content is the major determinant of assay sensitivity. Although this is true, false negatives can also be seen for complex variants such as gene fusions even when tumor content is high.24 More significantly, here we used a practical clinical measure of tumor content in cfDNA—a calculation of maximum AF—which can be inaccurate when there is allelic imbalance (eg, amplification or loss of heterozygosity). Others have used broad genomic analysis to derive measures of cfDNA tumor fraction,25 but such calculations are not routinely provided as part of plasma NGS results. Incorporation of a validated tumor fraction calculation would have the potential to be extremely valuable to clinicians as they gauge the adequacy of cfDNA specimens and the potential yield from additional tumor genotyping.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Kenneth Thress for his contributions to this work.

Appendix

FIG A1.

(A-D) Distinguishing true-positive and false-negative plasma NGS results using allele frequency (AF) and CN. Considering all variants detected in cell-free DNA but excluding mutations in the driver gene of interest for each case, sensitivity is clearly higher with detection of CN gains or high AF mutations. Notably, low AF mutations are common even in false-negative plasma NGS results. CN, copy number; ND, not detected; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

FIG A2.

Gene variants representing the maximum AF calculation. The majority of nontarget gene variants with the maximum AF in analyzed samples occurred in TP53. Other genes with variants calculated as maximum AF across multiple samples include NF1, PIK3CA, RB1, AKT1, ARID1A, JAK2, NOTCH1, PTEN, and STK11. AF, allele frequency.

Mark M. Awad

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Clovis Oncology, Nektar, Bristol Myers Squibb, ARIAD, Foundation Medicine, Syndax, Novartis, Blueprint Medicines, Maverick Therapeutics, Achilles Therapeutics, Neon Therapeutics, Hengrui Therapeutics, Gritstone Oncology, Archer, Mirati Therapeutics, NextCure, EMD Serono, AstraZeneca, Panasonic

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb

Michael S. Rabin

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Acuity Bio

Cloud P. Paweletz

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bio-Rad

Consulting or Advisory Role: DropWorks

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Ryan Hartmaier

Employment: AstraZeneca

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Inventor on patent application: US20190218618A1, status pending (assigned to Foundation Medicine, Genentech)

Gianluca Laus

Employment: AstraZeneca

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche

Honoraria: Guardant Health, Foundation Medicine

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Inivata, Takeda, Loxo, DropWorks, Grail, Janssen, Sysmex, Illumina, AbbVie, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: DFCI has a patent pending titled Noninvasive blood-based monitoring of genomic alterations in cancer, on which I am a coauthor

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

G.R.O. is the Damon Runyon-Gordon Family Clinical Investigator supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (Grant No. CI-86-16). Supported in part by the NIH (Grant No. R01 CA240592) and the Pamela Elizabeth Cooper Research Fund, the Expect Miracles Foundation, and the Robert and Renée Belfer Foundation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Catherine B. Meador, Cloud P. Paweletz, Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Financial support: Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Provision of study materials or patients: Michael S. Rabin, Ryan Hartmaier, Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Collection and assembly of data: Catherine B. Meador, Marina S. D. Milan, Emmy Y. Hu, Mark M. Awad, Ryan Hartmaier, Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Data analysis and interpretation: Catherine B. Meador, Marina S. D. Milan, Mark M. Awad, Michael S. Rabin, Ryan Hartmaier, Gianluca Laus, Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Mark M. Awad

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Clovis Oncology, Nektar, Bristol Myers Squibb, ARIAD, Foundation Medicine, Syndax, Novartis, Blueprint Medicines, Maverick Therapeutics, Achilles Therapeutics, Neon Therapeutics, Hengrui Therapeutics, Gritstone Oncology, Archer, Mirati Therapeutics, NextCure, EMD Serono, AstraZeneca, Panasonic

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb

Michael S. Rabin

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Acuity Bio

Cloud P. Paweletz

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bio-Rad

Consulting or Advisory Role: DropWorks

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Ryan Hartmaier

Employment: AstraZeneca

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Inventor on patent application: US20190218618A1, status pending (assigned to Foundation Medicine, Genentech)

Gianluca Laus

Employment: AstraZeneca

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Geoffrey R. Oxnard

Employment: Foundation Medicine

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche

Honoraria: Guardant Health, Foundation Medicine

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Inivata, Takeda, Loxo, DropWorks, Grail, Janssen, Sysmex, Illumina, AbbVie, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: DFCI has a patent pending titled Noninvasive blood-based monitoring of genomic alterations in cancer, on which I am a coauthor

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meador CB, Oxnard GR: Effective cancer genotyping-many means to one end. Clin Cancer Res 25:4583-4585, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C: The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 553:446-454, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal C, Thompson JC, Black TA, et al. : Clinical implications of plasma-based genotyping with the delivery of personalized therapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 5:173-180, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. : Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 350:2129-2139, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. : EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 304:1497-1500, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. : Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 361:947-957, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. : Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 11:121-128, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, et al. : AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 372:1689-1699, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, et al. : Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 376:629-640, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. : Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:113-125, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, et al. : Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 382:41-50, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacher AG, Paweletz C, Dahlberg SE, et al. : Prospective validation of rapid plasma genotyping for the detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations in advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2:1014-1022, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxnard GR, Thress KS, Alden RS, et al. : Association between plasma genotyping and outcomes of treatment with osimertinib (AZD9291) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:3375-3382, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray JE, Okamoto I, Sriuranpong V, et al. : Tissue and plasma EGFR mutation analysis in the FLAURA trial: Osimertinib versus comparator EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor as first-line treatment in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 25:6644-6652, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thress KS, Brant R, Carr TH, et al. : EGFR mutation detection in ctDNA from NSCLC patient plasma: A cross-platform comparison of leading technologies to support the clinical development of AZD9291. Lung Cancer 90:509-515, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Han JY, Ahn MJ, et al. : Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation analysis in tissue and plasma from the AURA3 trial: Osimertinib versus platinum-pemetrexed for T790M mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 126:373-380, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellert H, Foreman T, Jackson L, et al. : Development and clinical utility of a blood-based test service for the rapid identification of actionable mutations in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Mol Diagn 19:404-416, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Alden RS, Odegaard JI, et al. : Discrimination of germline EGFR T790M mutations in plasma cell-free DNA allows study of prevalence across 31,414 cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 23:7351-7359, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sholl LM, Do K, Shivdasani P, et al. : Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight 1:e87062, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrer I, Zugazagoitia J, Herbertz S, et al. : KRAS-Mutant non-small cell lung cancer: From biology to therapy. Lung Cancer 124:53-64, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y, Ulrich BC, Supplee J, et al. : False-positive plasma genotyping due to clonal hematopoiesis. Clin Cancer Res 24:4437-4443, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razavi P, Li BT, Brown DN, et al. : High-intensity sequencing reveals the sources of plasma circulating cell-free DNA variants. Nat Med 25:1928-1937, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li BT, Janku F, Jung B, et al. : Ultra-deep next-generation sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with advanced lung cancers: Results from the Actionable Genome Consortium. Ann Oncol 30:597-603, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Supplee JG, Milan MSD, Lim LP, et al. : Sensitivity of next-generation sequencing assays detecting oncogenic fusions in plasma cell-free DNA. Lung Cancer 134:96-99, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stover DG, Parsons HA, Ha G, et al. : Association of cell-free DNA tumor fraction and somatic copy number alterations with survival in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 36:543-553, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]