Abstract

Simple Summary

For over thirty years, contagious agalactia has been recognized as a mycoplasma disease affecting small ruminants caused by four different pathogens: Mycoplasma agalactiae, Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri, Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum and Mycoplasma putrefaciens which were previously thought to produce clinically similar diseases. Today, with major advances in diagnosis enabling the rapid identification by molecular methods of causative mycoplasmas from infected flocks, it is time to revisit this issue. In this paper, we discuss and argue the reasons to support Mycoplasma agalactiae infection as the sole cause of contagious agalactia.

Abstract

Contagious agalactia (CA) is suspected when small ruminants show all or several of the following clinical signs: mastitis, arthritis, keratoconjunctivitis and occasionally abortion. It is confirmed following mycoplasma isolation or detection. The historical and major cause is Mycoplasma agalactiae which was first isolated from sheep in 1923. Over the last thirty years, three other mycoplasmas (Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri, Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum and Mycoplasma putrefaciens) have been added to the etiology of CA because they can occasionally cause clinically similar outcomes though nearly always in goats. However, only M. agalactiae is subject to animal disease regulations nationally and internationally. Consequently, it makes little sense to list mycoplasmas other than M. agalactiae as causes of the OIE-listed CA when they are not officially reported by the veterinary authorities and unlikely to be so in the future. Indeed, encouraging countries just to report M. agalactiae may bring about a better understanding of the importance of CA. In conclusion, we recommend that CA should only be diagnosed and confirmed when M. agalactiae is detected either by isolation or molecular methods, and that the other three mycoplasmas be removed from the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines in Terrestrial Animals and associated sources.

Keywords: contagious agalactia, mycoplasmas, Mycoplasma agalactiae, etiology, small ruminants

1. Introduction

In 1999, the consensus of the working group on contagious agalactia (CA) of the EC COST Action 826 on ruminant mycoplasmoses, which met in Toulouse, France, agreed that four mycoplasmas—Mycoplasma agalactiae, M. mycoides subsp. capri (previously named M. m. mycoides large colony), M. capricolum subsp. capricolum and M. putrefaciens—should be recognized as causal agents of CA because the clinical disease they cause can be similar and includes mastitis, arthritis, keratoconjunctivitis and, occasionally, abortion [1]. This decision followed earlier observations by Perreau in 1979 [2] that clinical signs of infections causing M. agalactiae, the main and historical cause, were sufficiently similar to those of M. m. capri and M. c. capricolum to be considered CA. As a result, these were listed in the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines in Terrestrial Animals in 1988 [3]. Furthermore, Lambert, who compiled the chapter on CA, added another mycoplasma, M. putrefaciens, mainly based on a few reports including one from Da Massa et al. in 1987 describing a severe outbreak of mastitis and arthritis in goats requiring the slaughter of nearly 700 goats [4]. Despite the infrequency of reported cases of M. putrefaciens and, indeed, M. c. capricolum, the four mycoplasmas have continued to be listed in their manual by the OIE ever since as etiological agents of CA. The inclusion of all four mycoplasmas has not been without argument with the OIE Collaborating Centre for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics at Iowa State University commenting in 2004: “Some authorities consider infections with all of these agents to be CA; others prefer to reserve the term for infections with (only) M. agalactiae. Until this issue has been resolved, reports of CA outbreaks should specify the species involved” [5]. Unfortunately, few authorities have followed this advice even in the OIE’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code, World Animal Health publications or their online equivalents.

Today, with major advances in diagnosis enabling the rapid identification by molecular methods of causative mycoplasmas from infected small ruminants, which is required to confirm diagnosis of CA, it is belatedly time to revisit this issue. This is important because only M. agalactiae is recognized nationally and internationally and subject to animal disease regulations covering CA. While M. m. capri is a widespread and probably underestimated respiratory pathogen, the disease it causes is, in most cases, clinically distinct from that caused by M. agalactiae. M. c. capricolum also favors the respiratory system and is rarely reported, while M. putrefaciens can cause reduction in milk production but affected animals are often without clinical signs. Moreover, M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens are pathogens of goats rarely affecting sheep, which are by far the most economically important small ruminant species worldwide, particularly in the EU, where sheep numbers are seven times higher than those of goats [6]. For these reasons, the principal objective of this paper is to show that M. agalactiae should be considered the sole cause of classical CA.

2. General Consideration about Contagious Agalactia

2.1. Clinical Findings and Epidemiology

The main clinical signs of CA caused by M. agalactiae are mastitis which can involve 60–80% of lactating females, followed by arthritis, keratoconjunctivitis and abortion in less than 10% of affected animals. Clinical signs can be seen at various stages during the evolution of the disease, not necessarily in the same animal but in individuals in the affected flock or herd [7]. M. agalactiae accounts for 90% of outbreaks of CA in goats [8] and almost 100% in sheep [7]; it is characterized by high morbidity (sometimes up to 50 and 90% of the lactating female sheep and goats, respectively), drastic reduction of milk production and, in 90% of cases, the most visible sign, interstitial mastitis, is seen [9]. Arthritis and keratoconjunctivitis are normally observed in 5–10% of cases [10]. Respiratory disease is very rarely a feature of CA caused by M. agalactiae and, where it has been reported, may have been the result of a mixed infection with other pathogens, in particular M. m. capri [11].

The three other mycoplasmas which have been added to the etiology of CA can occasionally cause clinically similar outcomes, though exclusively in goats. However, the two pathogens belonging to the M. mycoides group, M. m. capri and M. c. capricolum, are more often isolated from pneumonic goats [12] or from polyarthritic kids [13] and only rarely reported in sheep in some areas [14].

In an effort to separate diseases caused by M. m. capri and other pulmonary mycoplasmas in goats from CA, Thiaucourt and Bolske used the rather awkward term MAKePs syndrome standing for mastitis, arthritis, keratoconjunctivitis and pneumonia [15]. Outbreaks often show high morbidity of up to 40, 80 and 90% in adults, lactating females and kids respectively; mastitis, on the other hand, is rarely reported compared to the other more predominant signs such as severe respiratory or poly-arthritic syndromes and, even less frequently, conjunctivitis, abortions and stillbirth [7].

The fourth listed mycoplasma M. putrefaciens is a very infrequent isolate from goats with questionable pathogenicity as it is often isolated from healthy goats but has been found occasionally in goat herds presenting agalactia. It is often found with M. agalactiae where it may play little role in disease progression [16,17]. However, De Massa et al. [4], reported a serious outbreak in the USA requiring the destruction of 700 goats. However, the authors concluded that poor hygiene involving infusion of the pathogen into the teat canal and the feeding of raw colostrum played a major part in the disease. Its pathogenicity seems primarily to depend on intrinsic and external hosts factors [7].

Overall, most countries involved in small ruminant dairy production identify M. agalactiae as the unique or major pathogen in CA. Some European countries also report to national authorities some or all of the three mycoplasmas, which may not always be linked to outbreaks of mastitis and/or falls in milk production. An investigation carried out between 2004 and 2012 in Sardinia, which has the highest sheep population in Italy, found a high number of outbreaks of M. m. capri. This was shown to be the result of introductions of goat breeds from Spain and other European countries. The disease was confirmed in 34 goat farms and a single sheep flock [18]. While the authors did not record the clinical signs of the individual herds, it is interesting to note that M. m. capri was isolated from the lungs and brains of over 74% of the herds, sites rarely associated with M. agalactiae (7).

Clinical signs of the four mycoplasmas are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of the contagious agalactia (CA) pathogens group.

| PATHOGENS | M. agalactiae |

M. m. capri

M. c. capricolum M. putrefaciens * |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| GENE CLUSTER | M. bovis | M. mycoides | |

| HOST SPECIES | Sheep; goats | Goats; sheep (±) | |

| CLINICAL FORM | sheep | subacute/chronic | Not reported |

| goats | acute/chronic | hyperacute/subacute (Mmc, Mcc) | |

| MORTALITY | sheep | low | Not reported |

| goats | low | High (especially in kids) | |

| MORBIDITY | sheep | >50% | Not reported |

| goats | >70% | >80% | |

| TYPICAL SYNDROMES | Mammary Articular Ocular Others |

Pulmonary Articular Ocular Others |

|

| PATHOLOGY | Frequent (>60% of cases) |

Chronic interstitial mastitis (Unilateral or bilateral) |

- Primary interstitial pneumonia and pleurisy; - Severe fibrin purulent polyarthritis; - Septicemia (kids) |

| Rare (<15% of cases) |

- Keratoconjunctivitis; - Fibrinopurulent arthritis; - Pneumonia and pleurisy; - Abortion |

- Chronic interstitial mastitis (unilateral or bilateral); - Keratoconjunctivitis; - Abortion |

|

* Very few clinical and pathological reports.

2.2. Pathological Findings in Experimental and Natural Infection

It can be difficult to make comparisons between infections caused by these various mycoplasmas because experimental infections do not always mimic natural infection as the pathogen may invade less aggressively either following contamination from the environment or the infected hands of the milkers. However, reports have shown quite distinct pathological changes following infection with different mycoplasmas. Moreover, lesions resulting from experimental infections of M. agalactiae vary according to the route of infection. Hasso and colleagues [19] reported an experimental infection with M. agalactiae testing four different routes of inoculation and observed: acute to chronic mastitis in the intramammary and subcutaneously inoculated groups; acute synovitis in the intravenously inoculated group and, to a lesser extent, in the intramammary inoculated group; and subacute enteritis in the orally inoculated group. No changes were detected in the eyes.

Other authors [20,21] have reported pathology induced by M. m. capri infection as a disease which involves mainly the thoracic cavity in adults and the joints of young animals. There was no mention of lesions in the mammary glands. Studies carried out in Italy some years ago [22] confirmed that M. m. capri infection was a respiratory and poly-arthritic syndrome and only one of ten experimentally infected goats had udder lesions detected by immunohistochemistry. Agnello et al. [15] investigated a natural outbreak in local goats caused by M. m. capri where few adult animals showed clinical signs or lesions, whereas a severe poly-arthritic syndrome was found in the 90% of kids with an 80% mortality rate.

Bergonier et al. [7] investigated the anatomic location of M. agalactiae and M. m. capri in goats following natural infection and showed that M. m. capri possessed a greater respiratory tropism than M. agalactiae. In addition, a large number of M. m. capri isolates were found in the ear canal, demonstrating a close connection between the respiratory system and the middle ear.

Pathological and immunohistochemical findings observed in 12 kids experimentally infected with M. c. capricolum, M. m. capri and M. m. mycoides (large colony type) showed fatal septicemia within 5 days; histopathological findings consisted of acute diffuse interstitial pneumonia, arthritis and multifocal necrotic purulent splenitis [23].

The few studies on M. putrefaciens pathology have shown that only intramammary inoculation can lead to an acute mastitis while other routes failed to produce lesions [24]; this may suggest the opportunistic nature of this mycoplasma probably overestimated for its pathogenic role. Experimental infection with M. putrefaciens strains in lactating goats via intramammary inoculation caused an increase of leukocytes in milk within 8 days but no sign of mastitis in spite of a complete halt in lactation after some days [25]. Pathological findings are summarized in Table 1.

Da Massa [24] reported as “cardinal lesions” of infections with M. c. capricolum, a fibrinopurulent polyarthritis and an acute, diffuse interstitial pneumonia. However, lactating goats exposed to low numbers of the organism via the teat canal experienced similar lesions as well as acute mastitis, agalactia and hardened udders.

2.3. Geographical Location

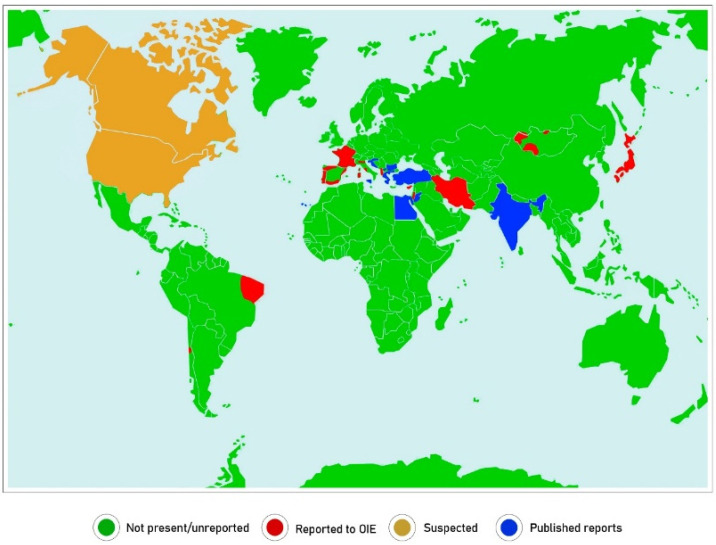

Of potential significance to our argument is the geographical distribution of the mycoplasmas and identification of regions where CA is reported. Unfortunately, this is difficult to be certain of as reports of CA by the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS) issued by the OIE do not specify the pathogen involved. Furthermore, many reporting countries do not have the ability or inclination to identify mycoplasmas, so diagnosis is mainly based on clinical disease. In countries where mycoplasma laboratories exist, CA is only declared when M. agalactiae is isolated. Indeed, few, if any, countries report CA officially when M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens are detected. Figure 1 shows the countries reporting CA in 2019, although some report that the disease is restricted to certain zones. These are surprisingly few and include, mostly, countries surrounding the Mediterranean and several in Western Asia and South America. The USA and Canada suspect the disease but there have been only sporadic reports of isolations of M. agalactiae and very few reports of the other causative mycoplasmas over the last 20 years [26]. Many other countries have reported isolations of these mycoplasmas but it seems regular monitoring does not take place. Jordan appears in the WAHIS “suspect” category but has reported most of these mycoplasmas several times [27]. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, cases of M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens in both sheep and goats have been reported [28]. In North Macedonia [29] and in Turkey [30], M. agalactiae appears to be dominant in both sheep and goats. In North and Central Spain, M. agalactiae is widely present in sheep but M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens remain unreported [31]. In Murcia, a mycoplasma survey of goats reported a high prevalence of CA (67%) dominated by M. agalactiae (75%) compared to M. m. capri (4%) [32]. In contrast, in the Canary Islands, the prevalence of M. m. capri in goats is similar to that of M. agalactiae [33].

Figure 1.

Countries reporting the mycoplasmas causing contagious agalactia worldwide.

In France, a national surveillance network estimated a prevalence of 42%, 26% and 15% for M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens respectively but rarely detected M. agalactiae in clinically affected goats [34]. In Italy, M. agalactiae is considered as a dominant pathogen in major sheep-breeding regions [12], whereas M. m. capri strains were also isolated in goats in Sardinia and Sicily [15]. In addition, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens were isolated from a few milk samples in Sardinia in 2018 (Tola, personal communication). In Greece and Cyprus, all reports in both sheep and goats have focused exclusively on M. agalactiae [35].

More recently, CA has been reported in countries in Western Asia like Iran and Mongolia where automation of the dairy industry is still rare. While isolation of M. m. capri has been reported in Australia and New Zealand, CA has never been diagnosed despite the large numbers of sheep probably because most are maintained for meat production. In general, M. agalactiae appears to have a more restricted distribution: Southern Europe, West Asia, including Turkey and Iran, and North Africa with occasional reports from parts of South America like Brazil [36]. On the other hand, M. m. capri has been reported on most continents of the world where small ruminants are kept. Reports of M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens are much more sporadic and infrequent.

2.4. Characteristics of the Causative Mycoplasmas

It is worth noting that M. agalactiae is very closely related to the bovine pathogen, M. bovis, and grouped in the hyorhinis group along with other animal pathogens. The other three mycoplasmas, M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens, belong or are very closely related to the genetically distant mycoides cluster surprisingly located in the spiroplasma group, mollicutes more commonly found in plants and insects. Indeed, M. agalactiae shares only 18% of its genome with the M. mycoides cluster [37]. Interestingly, data reports on antibiotic resistance profiles of CA-causing Mycoplasma spp. showed a marked difference in behavior in vitro. Erythromycin is effective against infection by M. m. capri, M. c. capricolum and M. putrefaciens, but inefficient against M. agalactiae strains [12,14,27]. This is an additional confirmation that there are two different kinds of diseases related to whether the pathogen is a member of the bovis or mycoides groups.

2.5. Legislation

In the United Kingdom, like many other disease-free countries, CA is a notifiable disease and is covered by two pieces of legislation: the Specific Diseases (Notification and Slaughter) Order 1992 and the Specific Diseases (Notification) Order 1996 which describe procedures to be taken, including movement restriction, slaughter and disinfection, in the event of an outbreak. However, action is only taken if M. agalactiae is suspected as was a recent case involving imported goats from France [38]. Poland also has specific legislation for CA but only enforceable if M. agalactiae is detected. Israel regularly isolates M. agalactiae and M. m. mycoides but only reports this nationally while informing the OIE that CA is present based on clinical findings. In many countries including Turkey and Portugal, cases of CA are not reported possibly because of the complexities of reporting several pathogens as causes of CA. In France, Greece, Iran and Italy as well, action is only taken in the event of the detection of M. agalactiae. Indeed, we do not know of any country that reports or takes action if any of the other causative mycoplasmas are found.

3. Discussion

In countries where M. agalactiae represents the most important and prevalent pathogen associated with CA, the disease shows the same clinical course both in sheep and goats. Moreover, in those countries like Italy where often both animal species are kept together in the same group, owners do not report any clinical differences between them. It seems to confirm that the clinical behavior of CA is quite different according to the pathogen involved, target species, breed, farm/husbandry type or degree of domestication. However, from a veterinary point of view, two different diseases are seen. First, the “typical or classical disease” which is very contagious affecting flock milk production and for this reason is called “contagious agalactia”. This disease occurs exclusively in milking/dairy small ruminants. In the ancestral species, the Spanish ibex (Capra pirenaica), the clinical signs are represented by blindness, malnutrition and polyarthritis [39], but there are no reports of mastitis probably because this lesion is mainly related to the last phase of species domestication and its dairy purpose. The second clinical syndrome related to CA is linked to the other mycoplasma infections and generally causes other clinical signs probably initiating in the respiratory tract of adult goats and joints in kids; only a small percentage of infections may involve the udder.

The introduction of European Union (EU) regulation 2016/429, which provided a new regulatory framework covering control and surveillance of infectious diseases, animal welfare and animal movements amongst Member States, complements local legislation but also reduces the amount of intervention possible [40]. Worryingly, this directive will impact some traditionally notifiable diseases, including CA, and remove them from the new EU disease-listing process, with control being devolved to the national or even local level. This apparent downgrading of the importance of CA may negatively affect international collaboration on control across borders and make this disease a less likely area for research funding. Delisting of CA from EU notifiable diseases [41] associated with the absence of surveillance plans and of any other mandatory certification for trades may also facilitate the risk of introduction of CA “healthy carriers” in CA-free small ruminant populations which may enable a massive spreading of the disease. Conversely, the identification of M. agalactiae as a single cause of CA may help focus attention on this important pathogen and remove the confusion and uncertainty that exists about reporting of this OIE-listed disease. This will also fit better into the OIE ethos of “one disease, one cause”. It is hoped that this paper may cause the EU to reconsider altering the status of CA in future amendments to the regulation as we believe it is an under-reported disease with international significance.

Finally, in a further effort to bring about clarity to this complex area we propose a new term for the disease caused by the largely respiratory pathogens M. m. capri and M. c. capricolum: caprine respiratory and articular syndrome (CRAS). This reflects more accurately the main disease signs and separates it from the OIE-listed contagious caprine pleuropneumonia caused by the closely related M. capricolum subsp. capripneumoniae which is confined to the thoracic cavity.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we recommend that CA should only be diagnosed and confirmed when M. agalactiae is detected either by isolation or molecular methods such as PCR and the other three mycoplasmas removed from the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines in Terrestrial Animals and associated sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fabrizio Chiruzzi for graphic support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., R.P., R.A.J.N. and G.R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, S.M., R.P., R.A.J.N. and G.R.L.; supervision, R.A.J.N. and G.R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (Terrestrial Manual) 8th ed. Volume 1. OIE; Paris, France: 2019. [(accessed on 1 May 2021)]. Chapter 3.7.3 Contagious Agalactia; pp. 1430–1440. Available online: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/ Health_standards/tahm/3.07.03_CONT_AGALACT.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perreau P. Les mycoplasmoses de la chevre. Cah. Med. Vet. 1979;48:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholas R.A.J. Contagious Agalactia: An update. In: Frey J., Sarris K., editors. Mycoplasmas of Ruminants: Pathogenicity, Diagnostics, Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics. Commission of the European Community; Luxembourg: 1996. pp. 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Massa A.J., Brooks D.L., Holmberg C.A., Moe A.I. Caprine mycoplasmosis: An outbreak of mastitis and arthritis requiring the destruction of 700 goats. Vet. Rec. 1987;120:409–413. doi: 10.1136/vr.120.17.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spickler A.R. Contagious Agalactia. [(accessed on 22 April 2021)]; Available online: cfsph.iastate.edu/diseaseinfo/factsheets/ https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/diseaseinfo/disease/?disease=contagious-agalactia&lang=en.

- 6.European Parliamentary Research Service The Sheep and Goat Sector in the EU Main Features, Challenges and Prospects. Briefing. [(accessed on 21 April 2021)];2017 Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/608663/E.

- 7.Bergonier D., Berthelot X., Poumarat F. Contagious agalactia of small ruminants: Current knowledge concerning epidemiology, diagnosis and control. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1997;16:848–873. doi: 10.20506/rst.16.3.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrido F., Leon J.L., Cuellar L., Diaz M.A. In: Contagious Agalactia and Other Mycoplasmal Diseases of Ruminants. Lambert M., Jones G., editors. Commission of the European Community; Luxembourg: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loria G.R., Nicholas R.A. Contagious agalactia: The shepherd’s nightmare. Vet. J. 2013;198:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolone M., Sutera A.M., Borrello S., Tumino S., Scatassa M.L., Portolano B., Puleio R., Nicholas R.A.J., Loria G.R. Effect of Mycoplasma agalactiae mastitis on milk production and composition in Valle dell Belice dairy sheep. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019;18:1067–1072. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2019.1617044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaÿ M., Tardy F. Contagious Agalactia In Sheep And Goats: Current Perspectives. Vet. Med. 2019;10:229–247. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S201847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De La Fe C., Gutiérrez A., Poveda J.B., Assunção P., Ramirez A.S., Fabelo F. First isolation of Mycoplasma capricolum subsp capricolum, one of the causal agents of caprine contagious agalactia, on the island of Lanzarote (Spain) Vet. J. 2005;173:440–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agnello S., Chetta M., Vicari D., Mancuso R., Manno C., Puleio R., Console A., Nicholas R.A., Loria G.R. Severe outbreaks of polyarthritis in kids caused by Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies capri in Sicily. Vet. Rec. 2012;170:416. doi: 10.1136/vr.100481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gómez-Martín A., Amores J., Paterna A., De la Fe C. Contagious agalactia due to Mycoplasma spp. in small dairy ruminants: Epidemiology and prospects for diagnosis and control. Vet. J. 2013;198:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiaucourt F., Bölske G. Contagious caprine pleuropneumonia and other pulmonary mycoplasmoses of sheep and goats. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1996;15:1397–1414. doi: 10.20506/rst.15.4.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil M.C., Peña F.J., Hermoso De Mendoza J., Gomez L. Genital lesions in an outbreak of caprine contagious agalactia caused by Mycoplasma agalactiae and Mycoplasma putrefaciens. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health. 2003;50:484–487. doi: 10.1046/j.0931-1793.2003.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajizadeh A., Ghaderi R., Ayling R.D. Species of Mycoplasma causing contagious agalactia in small ruminants in Northwest Iran. Vet. Ital. 2018;54:205–210. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.831.4072.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corona L., Amores J., Onni T., de la Fe C., Tola S. Characterization of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri isolates by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting and PFGE. Small Rumin. Res. 2013;115:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2013.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasso S.A., Al-Omran A.H. Antibody response patterns in goats experimentally infected with Mycoplasma agalactiae. Small Rumin. Res. 1994;14:79–81. doi: 10.1016/0921-4488(94)90014-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson G.C., Fales W.H., Shoemake B.M., Adkins P.R., Middleton J.R., Williams F., III, Zinn M., Mitchell W.J., Calcutt M.J. An outbreak of Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies capri arthritis in young goats: A case study. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2019;31:453–457. doi: 10.1177/1040638719835243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatay-Dualde J., Prats-van der Ham M., de la Fe C., Gómez-Martín Á., Paterna A., Corrales J.C., Contreras A., Sánchez A. Multilocus sequence typing of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri to assess its genetic variability in a contagious agalactia endemic area. Vet. Microbiol. 2016;191:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Angelo A.R., Di Provvido A., Di Francesco G., Sacchini F., De Caro C., Nicholas R.A., Scacchia M. Experimental infection of goats with an unusual strain of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri isolated in Jordan: Comparison of different diagnostic methods. Vet. Ital. 2010;46:189–207. (In English and Italian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez J.L., Gutiérrez C., Brooks D.L., DaMassa A.J., Orós J., Fernández A. A pathological and immunohistochemical study of goat kids undergoing septicaemic disease caused by Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum, Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri and Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides (large colony type) Zent. Vet. B. 1998;45:141–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1998.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DaMassa A.J., Brooks D.L., Holmberg C.A. Pathogenicity of Mycoplasma capricolum and Mycoplasma putrefaciens. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1984;20:975–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler H.E., DaMassa A.J., Brooks D.L. Caprine mycoplasmosis: Mycoplasma putrefaciens, a new cause of mastitis in goats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1980;41:1677–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OIE Animal Health Information WAHIS Interface; 2005–2019. [(accessed on 11 January 2021)]; Available online: https://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Diseaseinformation/Diseasetimelines/index/newlang/en?header_disease_type_hidden=0&header_disease_id_hidden=0&header_selected_disease_name_hidden=0&header_disease_type=0&header_disease_id_terrestrial=47&header_disease_id_aquatic=−999&header_firstyear=2005&header_lastyear=2019.

- 27.Al-Momani W., Halablab M.A., Abo-Shehada M.N., Miles K., McAuliffe L., Nicholas R.A.J. Isolation and molecular identification of small ruminant mycoplasmas in Jordan. Small Rumin. Res. 2006;65:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2005.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maksimovic Z., Bacic A., Rifatbegovic M. Mycoplasmas isolated from ruminants in Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1995 and 2015. Veterinaria. 2016;65:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cokrevski S., Crcev D., Loria G.R., Nicholas R.A.J. Outbreaks of contagious agalactia in small ruminants in the Republic of Macedonia. Vet. Rec. 2001;148:667. doi: 10.1136/vr.148.21.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goçmen H., Rosales R., Ayling R., Ülgen M. Comparison of PCR tests for the detection of Mycoplasma agalactiae in sheep and goats. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2016;40:421–427. doi: 10.3906/vet-1511-65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ariza-Miguel J., Rodriguez-Lazaro D., Hernandez M. A survey of Mycoplasma agalactiae in dairy sheep farms in Spain. BMC Vet. Res. 2012;8:171. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amores J., Sánchez A., Gómez-Martín Á., Corrales J.C., Contreras A., de la Fe C. Surveillance of Mycoplasma agalactiae and Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri in dairy goat herds. Small Rumin. Res. 2012;102:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De La Fe C., Assunção P., Antunes T., Rosales R.S., Poveda J.B. Microbiological survey for Mycoplasma spp. in a contagious agalactia endemic area. Vet. J. 2005;170:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chazel M., Tardy F., Le Grand D., Calavas D., Poumarat F. Mycoplasmoses of ruminants in France: Recent data from the national surveillance network. BMC Vet. Res. 2010;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filioussis G., Giadinis N.D., Petridou E.J., Karavanis E., Papageorgiou K., Karatzias H. Congenital polyarthritis in goat kids attributed to Mycoplasma agalactiae. Vet. Rec. 2011;169:364. doi: 10.1136/vr.d4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruno H.L.S., Alves J.G.S., Mota A.R., Campos A.C., Junior J.W.P., Santos S.R., Mota R.A. Mycoplasma aagalctiae in semen and milk of goat from Pernambuco, Brazil. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2013;33:1309–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirand-Pugnet P., Citti C., Barré A., Blanchard A. Evolution of mollicutes: Down a bumpy road with twists and turns. Res. Microbiol. 2007;158:754–766. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loria G.R., Puleio R., Filioussis G., Rosales R.S., Nicholas R.A.J. Contagious Agalactia: Costs and Control Revisited Scientific and Technical Review. Volume 38. OIE; Paris, France: 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verbisck-Bucker G., González-Candela M., Galián J., Cubero-Pablo M.J., Martín-Atance P., León-Vizcaíno L. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma agalactiae infection in free-ranging Spanish ibex (Capra pyrenaica) in Andalusia, southern Spain. J. Wildl. Dis. 2008;44:369–380. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loria G.R., Ruocco L., Ciaccio G., Iovino F., Nicholas R.A.J., Borrello S. The Implications of EU Regulation 2016/429 on Neglected Diseases of Small Ruminants including Contagious Agalactia with Particular Reference to Italy. Animals. 2010;10:900. doi: 10.3390/ani10050900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1629 of 25 July 2018 Amending the List of Diseases Set Out in Annex II to Regulation (EU) 2016/429 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Transmissible Animal Diseases and Amending and Repealing Certain Acts in the Area of Animal Health (Animal Health Law) Commission Delegated Regulation (EU); Brussels, Belgium: Jul 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]