Abstract

Background/Objective:

It is unknown whether older adults at high risk of falls but without cognitive impairment have higher rates of subsequent cognitive impairment.

Design:

This was an analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data from NHATS.

Setting:

National Health and Aging Trends Study, secondary analysis of data from 2011-2019

Participants:

Community dwelling adults age 65 and over without cognitive impairment

Measurements:

Participants were classified at baseline in three categories of fall risk (low, moderate, severe) using a modified algorithm from the Center for Disease Control’s STEADI (Stop Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries) and fall risk from data from the longitudinal National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Impaired global cognition was defined as NHATS-derived impairment in either the Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score, immediate/delayed recall, orientation, clock-drawing test, or date/person recall. The primary outcome was the first incident of cognitive impairment in an 8 year follow-up period. Cox-proportional hazard models ascertained time to onset of cognitive impairment (referent = low modified STEADI incidence).

Results:

Of the 7,146 participants (57.8% female), the median age category was 75-80 years. Prevalence of baseline fall modified STEADI risk categories in participants was low (51.6%), medium (38.5%) and high (9.9%). In our fully adjusted model, the risk of developing cognitive impairment was HR 1.18 [95%CI: 1.08, 1.29] in the moderate risk category, and HR 1.74 [95%CI: 1.53, 1.98] in the high-risk category.

Conclusions:

Older, cognitively intact adults at high fall risk at baseline had nearly twice the risk of cognitive decline at 8 year follow up.

Keywords: cognitive decline, dementia, fall, frequent falls

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with cognitive impairment are at a higher risk of falling but it is unclear if baseline fall risk has the ability to predict subsequent cognitive impairment1. Cognitive changes and factors that affect fall risk, such as gait speed, are more related than previously thought involving many similar brain processes and function 5. Motor changes may not only precede the onset of cognitive impairment, but may demonstrate progressive motor deterioration as individuals progress from normal cognition to dementia6, 7. Therefore, it is plausible that the concurrent changes observed with changes in mobility or cognition, may be related to each other, including the risk for future falls. Deterioration in cognition or mobility alone could inherently affect the other8.

To our knowledge, two studies have evaluated the question of whether gait speed in older adults predicts subsequent cognitive impairment. These two studies showed those with impaired gait speed had increased rates of new cognitive impairment at up to 6 year follow-up 13, 14. Another study showed that those with normal cognition and neurologic gait abnormalities (ie. Parkinsonian, spastic, frontal, neuropathic or hemiparetic gait as determined by a neurologist) were more likely to develop dementia, particularly non-Alzheimer’s dementia, within 6 years15. These studies have investigated the relationship between gait speed and gait abnormalities which are indirect measures of an individual’s potential fall risk. Examining an individual’s future fall risk using a fall risk algorithm and correlating it with the development of cognitive impairment to our knowledge, has not been evaluated.

STEADI is a tool developed by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) designed to be used by primary care providers as a more coordinated approach fall risk assessment and as a resource for educational material for older adults regarding falls and fall risk4. STEADI includes an adapted evidenced-based gait and balance assessment algorithm that simplifies and streamlines the fall risk assessment. The algorithm uses falls or fall-related injuries, confidence, or a fear of falling, combined with objective physical performance measures of gait and balance. Individuals are then stratified into fall risk categories. We previously demonstrated that risk categories predict future fall risk and frailty16, 17. The aim of the current study was to evaluate if using a modified version of the STEADI algorithm’s ability to predict the risk for future cognitive impairment in older adults without cognitive impairment at baseline using 8 years of survey data.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This study was a secondary analysis of existing collected data. We identified participants ≥65 years old that were interviewed and followed over an 8 year period using the National Health and Aging Trend Study (NHATS) (baseline 2011).NHATS is an ongoing longitudinal study that annually interviews a nationally representative cohort of older adults in the United States, funded by the National Institute on Aging and administered by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. It oversamples non-Hispanic blacks and individuals older than 90 years of age to investigate trends in late-life functioning18. For the purposes of this analysis, eight waves of data were used from participants who entered the cohort in 2011 wave. The data collected reflected physical and cognitive health, social, physical environment and actualization of activities of daily living (http://www.nhats.org/sresearcher/nhats/methods-docuementation?id=user_guide). NHATS uses standardized assessments in addition to self-reported data to measure physical function.18. Round 1 data included 8,245 Medicare beneficiaries randomly subsampled from the Medicare enrollment database who were living in contiguous United States. Cognitive and physical assessments were performed in person by trained research staff in the homes of participants 19.

We excluded those with known cognitive impairment and those with unknown cognitive status at baseline (see study variables for definitions). Our study focuses on community-dwelling older adults therefore we also excluded nursing home residents (n=468) some of which had been excluded by other exclusion measures. The final sample size of the baseline cohort was 7146 participants.

The local Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College and at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill exempted this study from review due to the de-identified nature of the data.

Study Variables

Our primary outcome was the presence of incident cognitive impairment over time. The combined outcome of cognitive impairment by combining the response to Alzheimer’s Disease-8, if available, with scores from each of the three cognitive domains (memory, performance on the clock drawing test, orientation). The AD-8 score was taken into consideration first; a score of ≥2 automatically classified participants into the ‘probably’ dementia category. If participant AD-8 score was unavailable, the individual domains were considered. The CDT was a surrogate for executive function (maximum score 5, cutoff of 1); the memory domain was determine by the combined score of immediate 10-word recall and delayed 10-word recall tests (maximum score 20, cutoff 3); and the orientation domain was calculated by the combined score of the date recall and president/vice-president naming tests (maximum score of 8, cutoff 3). Refusal or an inability to perform the test resulted in a score of zero.

For each of the three classifications, cognitive impairment was defined as 1.5 times the standard deviation below the mean score. Cognitive impairment in none of the domains was classified as ‘no dementia’; one domain as ‘possible dementia’; two or more domains as ‘probably dementia’. These were classified per the NHATS analytical guidelines (www.nhats.org/scripts/sampledesign) and Technical Paper #5. The combined dementia score was dichotomized with ‘possible dementia’ and ‘probable dementia’ into a single class, presence of cognitive impairment.

Fall Risk

Fall risk was assessed using an adapted version of the STEADI algorithm4, 17 based on our available data (Supplementary Figure 3), termed ‘modified’ STEADI algorithm. Participants were labeled as low risk for falls if they answered ‘no’ to all questions: “Have you fallen in the last year” “Are you worried about falling down” or “Do you feel unsafe standing or walking.” If they answered yes to at least one question, participants were further stratified by scores on physical functioning testing. We used the Four Stage Balance Test and Five Time Sit to Stand Test (FTSTS) to evaluate function. According to the Four Stage Balance Test outlined by the CDC, an older adult who is unable to hold a tandem stance for at least 10 seconds is at increased risk of falling 4. The FTSTS evaluates lower extremity strength and is associated with dysfunction in balance and mobility 20. Completion of less than 5 repetitions of sit to stand in 15 seconds is associated with increased risk of falling 21. If the participant completed both the Four Stage Balance and the FTSTS tests, they were stratified as low risk for falls. Alternatively, if they were unable to perform either of these tests participants were further stratified based on their response to the questions: “have you have multiple falls in the last year” or “have you broken a hip since age 50.” If they answered ‘yes’ to either question they were categorized as high risk while an answer of ‘no’ to both questions would categorize them as moderate risk. We considered participants who were ineligible for physical assessments due to pain, recent surgery, or lack of facilities to be missing respective physical measures.

Covariates

Demographic variables included self-reported age, sex, and education. We also assessed smoking status and race/ethnicity. Age was categorized in five-year increments from 65 to 85 and 85+. As age was considered a restricted variable, our approach was guided by previously published NHATS studies22, 23. Participants were classified “current”, “former”, or “never” smokers. We assessed physical activity based on yes or no response to “In the last month did you ever go walking for exercise?” We categorized race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic other. Presence of chronic health conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, probable dementia, stroke non-skin cancer based were identified using a self-reported questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous variables are represented as mean or β-coefficients ± standard errors and categorical variables are represented as counts (percent). We estimated the distribution of demographic and health-related variables in the analytic sample and compared these characteristics across fall risk categories using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. The primary outcome was the first occurrence of cognitive impairment, with cognitive outcomes and tests binarized in accordance with established NHATS guidelines. Our referent variable was individuals at low modified-STEADI fall risk. Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to estimate incident cognitive impairment hazard ratios with respect to the fall risk categories. Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age group, race/ethnicity, sex, education); Model 3 included model 2 additionally adjusted for chronic health conditions (heart disease, hypertension, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, cancer). We modeled time-to-event as continuous, though we acknowledge that because NHATS performs data collection on a yearly basis, incident cognitive impairment is best characterized as interval-censored data. However, given the number of follow up years and the inherent imprecision and variability in cognitive assessment, we expect that a standard Cox proportional hazards model serves as an adequate approximation.

We also looked at the association of fall risk with cognitive performance longitudinally using linear mixed effect modeling. Here, we modeled the various cognitive domains and individual cognitive tests as continuous outcomes, with the intercepts for individual respondents as random effects which accounts for the non-independence of the repeated measures in our survey data.

All analyses were done using R version 3.5.2 (www.R-project.org). Data wrangling was conducted using tidyverse (v. 1.2.1) and linear mixed effects modeling with package lme4 (v. 1.1.20) and ImerTest (v. 3.1.0). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 7,146 participants, 57.8% were females and median age category was 75-80 years. The majority of the participants were non-Hispanic whites (Table 1). Based on the modified-STEADI criteria 3,685 (51.6%), 2,753 (38.5%), and 708 (9.9%) individuals classified as low, moderate and high fall risk, respectively. Participants with high fall risk were more likely to be females, older, have more comorbidities and decreased physical activity. Smoking was not shown to be affected by modified-STEADI fall risk classification.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Low Risk | Medium Risk | High Risk | Overall | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3685 | N = 2753 | N = 708 | N = 7146 | ||

| Rates | 51.6 | 38.5 | 9.9 | ||

| Age, years | p<0.001 | ||||

| 65-69 | 873 (23.7) | 459 (16.7) | 64 (9.0) | 1396 (19.5) | |

| 70-74 | 931 (25.3) | 515 (18.7) | 101 (14.3) | 1547 (21.6) | |

| 75-79 | 748 (20.3) | 560 (20.3) | 128 (18.1) | 1436 (20.1) | |

| 80-84 | 637 (17.3) | 576 (20.9) | 182 (25.7) | 1395 (19.5) | |

| 85+ | 496 (13.5) | 643 (23.4) | 233 (32.9) | 1372 (19.2) | |

| Female | 1906 (51.7) | 1755 (63.7) | 470 (66.4) | 4131 (57.8) | p<0.001 |

| Race | p<0.001 | ||||

| White | 2489 (67.5) | 1930 (70.1) | 502 (70.9) | 4921 (68.9) | |

| Black | 849 (23.0) | 553 (20.1) | 131 (18.5) | 1533 (21.5) | |

| Hispanic | 184 (5.0) | 168 (6.1) | 58 (8.2) | 410 (5.7) | |

| Other | 120 (3.3) | 70 (2.5) | 14 (2.0) | 204 (2.9) | |

| Don’t Know/Refused | 43 (1.2) | 32 (1.2) | 3 (0.4) | 78 (1.1) | |

| Smoking Status | p=0.35 | ||||

| Current | 304 (8.2) | 213 (7.7) | 46 (6.5) | 563 (7.9) | |

| Former | 1599 (43.3) | 1159 (42.1) | 305 (43.1) | 3063 (42.9) | |

| Never | 1776 (48.2) | 1379 (50.1) | 357 (50.4) | 3512 (49.1) | |

| Not reported | 6 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.1) | |

| Education | p<0.001 | ||||

| Less than high school degree | 877 (23.8) | 727 (26.4) | 255 (36.0) | 1859 (26.0) | |

| High school to some college | 1718 (46.6) | 1323 (48.1) | 334 (47.2) | 3375 (47.2) | |

| College degree | 627 (17.0) | 441 (16.0) | 76 (10.7) | 1144 (16.0) | |

| Greater than College degree | 422 (11.5) | 233 (8.5) | 39 (5.5) | 694 (9.7) | |

| Not reported | 41 (1.1) | 29 (1.1) | 4 (0.6) | 74 (1.0) | |

| Physical Activity | p<0.001 | ||||

| Ever walk for exercise | 2475 (67.2) | 1448 (52.6) | 287 (40.5) | 4210 (58.9) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Heart Disease | 727 (19.7) | 820 (29.8) | 291 (41.1) | 1838 (25.7) | p<0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2288 (62.1) | 1954 (71.0) | 532 (75.1) | 4774 (66.8) | p<0.001 |

| Arthritis | 1616 (43.9) | 1802 (65.5) | 52 (73.4) | 3938 (55.1) | p<0.001 |

| Diabetes | 768 (20.8) | 753 (27.4) | 282 (39.8) | 1803 (25.2) | p<0.001 |

| Lung Disease | 412 (11.2) | 488 (17.7) | 175 (24.7) | 1075 (15.0) | p<0.001 |

| Stroke | 253 (6.9) | 350 (12.7) | 159 (22.5) | 762 (10.7) | p<0.001 |

| Cancer | 869 (23.6) | 766 (27.8) | 203 (28.7) | 1838 (25.7) | p<0.001 |

Values represented are counts (percentages). Chi-square test used for all categorical characteristic p-values.

The adjusted hazard of an individual in the moderate and high risk categories developing cognitive impairment (Model 3) were 18% and 74% higher than that of an individual identified as being of low fall risk, respectively (HR 1.18 [95% CI: 1.08-1.29] and HR 1.74 [95% CI: 1.53, 1.98]). Full results of all modeling are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Development of Cognitive Impairment Eight Years from Stratification by Modified STEADI Fall Risk Using Cox-Proportional Hazard Model

| Cognitive Impairment┼ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Cognitive |

Clock Drawing Performance |

Memory | Orientation | ||

| STEADI Categorization* | |||||

| Model 1 | Medium Risk HR, [95% CI] | 1.37 (1.26-1.49) |

1.31 (1.17-1.48) |

1.39 (1.26-1.53) |

1.46 (1.3-1.64) |

|

High Risk HR, [95% CI] |

2.58 (2.29-2.91) |

2.22 (1.89-2.6) |

2.41 (2.11-2.76) |

2.63 (2.25-3.08) |

|

| Model 2 | Medium Risk HR, [95% CI] | 1.37 (1.26-1.49) |

1.31 (1.17-1.48) |

1.39 (1.26-1.53) |

1.46 (1.3-1.64) |

| High Risk HR, [95% CI] | 2.58 (2.29-2.91) |

2.22 (1.89-2.6) |

2.41 (2.11-2.76) |

2.63 (2.25-3.08) |

|

| Model 3 | Medium Risk HR, [95% CI] | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) |

1.2 (1.06-1.36) |

1.2 (1.09-1.33) |

1.26 (1.12-1.43) |

| High Risk HR, [95% CI] | 1.74 (1.53-1.98) |

1.69 (1.42-2.01) |

1.65 (1.43-1.9) |

1.78 (1.51-2.11) |

|

All values represent hazard ratio [95% confidence intervals] based on an adjusted Cox-Proportional Hazard Model over an 8 year period of time. Model 1: unadjusted; Model 2: adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, sex, education; Model 3: adjusted for age category, sex, smoking, education plus comorbidities (heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, cancer, ever walk for exercise)

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Combined Dementia – combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washing University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1, 2 or 3). Executive function consists of clock drawing test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Table 3 reports the difference in mean categories between the medium and high-risk fall groups and the low risk referent group. This shows the relationship between fall risk categories and cognitive score in both the medium and high-risk groups to be significant in all cognitive subdomains. Additionally, both the medium and high-risk category were significantly associated with the combined cognitive score, results that are in agreement with our time-to-event analyses.

Table 3:

Association of Fall Risk with Average Scores Over Time Using Linear Mixed Effect Modeling

| β±s.e. | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Combined | ||

| Medium Risk | 0.064 ± 0.016 | <0.001 |

| High Risk | 0.247 ± 0.027 | <0.001 |

| Self-Rated Memory | ||

| Medium Risk | 0.261 ± 0.021 | <0.001 |

| High Risk | 0.348 ± 0.036 | <0.001 |

| MEMORY DOMAIN | ||

| Immediate Recall | ||

| Medium Risk | −0.165 ± 0.034 | <0.001 |

| High Risk | −0.544 ± 0.058 | <0.001 |

| Delayed Recall | ||

| Medium Risk | −0.143 ± 0.040 | <0.001 |

| High Risk | −0.519 ± 0.067 | <0.001 |

| ORIENTATION | ||

| Medium Risk | −0.134 ± 0.039 | 0.001 |

| High Risk | −0.476 ± 0.065 | <0.001 |

| EXECUTIVE FUNCTION | ||

| Clock Test | ||

| Medium Risk | −0.086 ± 0.023 | <0.001 |

| High Risk | −0.321 ± 0.039 | <0.001 |

Results are β coefficients ± standard errors/p-values over an 8 year period of time based on Model 3: adjusted for age category, sex, smoking, education plus comorbidities (heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, cancer, ever walk for exercise)

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Combined Dementia – Sum of 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1, 2 or 3). Executive function consists of clock drawing test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

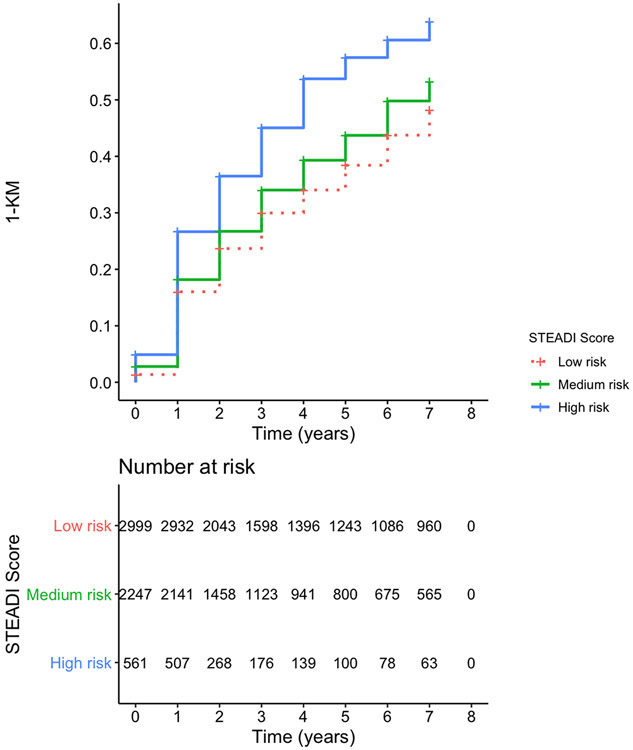

Figure 1 depicts the 1-Kaplan-Meier curve to cognitive impairment stratified by modified-STEADI fall risk categories, showing the higher rates of cognitive impairment in respondents in higher initial fall risk categories using model 3 data. Kaplan Meier curves for model 1 and 2 data can be found in the supplementary figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1. 1- KM Curve for Cognitive Impairment by Modified STEADI Categories Risk Based on Model 3 Data.

Results are adjusted for age category, gender, smoking, education plus comorbidities including heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, cancer, ever walk for exercise. Figure counts represent those at risk in each modified STEADI category. The number of at-risk individuals is displayed at each time point.

Combined Dementia is a combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washington University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1,2, or 3). Clock draw test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that older adults with normal baseline cognition who are at high fall risk have a 74% higher risk of developing cognitive impairment as compared to their low fall risk peers over an 8 year period of time.

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome is a recently defined concept suggesting a “pre-dementia syndrome” and consists of the presence of mild cognitive impairment and slower gait speed in older adults24. This geriatric syndrome is highly predictive of future risk of dementia more so than either gait speed or mild cognitive impairment alone; testing this hypothesis has shown that motor decline defined by gait speed accelerates up to 12 years before mild cognitive impairment is even detected25. Lower gait speed is associated with a higher risk of falling26 while gait speed and falling are different, but related constructs, our analysis advances the science by suggesting a relationship with cognitive impairment, evoking the possibility of a bi-directional relationship with a modified fall risk algorithm. Future studies can now examine if the use of a modified STEADI algorithm coupled with a formal and validated cognitive tool such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)2 or Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE)27 may improve the predictive capability for future cognitive decline while concurrently evaluating an individual’s fall risk.

Fall risk is linked to multiple organ systems and overall health and function 28 suggesting that multiple factors are likely contributing to the increased rate of cognitive decline in those at higher fall risk. It has been shown that slower gait speed at baseline may be associated with greater cognitive decline with the most effect seen in the subdomain of executive function14. Dual tasking in older adults may have more appreciable issues with gait and balance when asked to walk and perform a secondary task; this suggests a strong component of decline in executive function as a contributing factor29, 30. Executive function involves higher-order cognitive process that control and integrate our cognitive abilities, and when impaired, may lead to increased fall risk due to its effect on judgement and motor planning31, 32. Our findings provide emerging evidence that a modified STEADI algorithm could potentially help identify those at risk for incident cognitive decline.

Our study has a number of strengths including a large sample size and objective measures to define gait speed, balance, mobility and strength in stratifying participants into fall risk categories. We relied on NHATS’ standardized cognitive analysis which implements the Washington Dementia Screening Test (AD8) that has a positive predictive value of >85% and negative predictive value of >70% for identifying cognitively impaired participants 42. The AD8 combined with the Mini-Cog greatly enhances the ability to capture early cognitive change 43. Using the validated STEADI tool and applying it to NHATS in our modified form has been well validated in our previous studies adapting the algorithm to existing survey data requiring some modifications and simplifications however as shown previously still resulting in a strong association between risk categories and falls 16, 17. STEADI suggests Timed Up and Go (TUG) testing in addition to strength and balance testing; however, other than physical assessment measures, all data was otherwise self-reported. STEADI further stratifies patients based on injury, yet NHATS only categorizes injury based on a history of hip fracture therefore other injuries acquired from past falls could have stratified some patients differently among moderate and high fall risk groups.

This study has several limitations. First, as with any survey analysis, we recognized selection bias. Second, our analysis did not adjust for factors that could be mediators rather than cofounders for the future development of cognitive impairment (e.g., mobility restriction, polypharmacy or hospitalization). While such factors may be associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, our study objective was to determine whether baseline risk predicted future impairment. This was in contrast to ascertaining cognitive trajectories or to ascertain potential mediators, which could be evaluated in future studies. The long follow-up in NHATS provides an opportunity for a future analysis. Third, in addition, NHATS relies on considerable self-report data, and the interval nature may lead to inaccuracies between survey years. Our data also does not adjust for our baseline dependent variable of cognitive function as may reduce some biases, but may introduce other biases that maybe more detrimental to the outcome itself 44. Fourth, elements of social or occupational function may also impact cognitive trajectories and future studies should be considered to evaluate these mediating effects. Last, we relied on the NHATS definitions for cognitive impairment rather than standardized tools such as the MMSE or MOCA.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show a relationship between elevated fall risk and incident cognitive impairment in those free of cognitive dysfunction at baseline. While our findings are suggestive, future longitudinal cohort studies are needed to validate such findings to ascertain the ability of STEADI to act as a marker for neurodegenerative or vascular pathologies preceding formal cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. 1- KM Curve for Cognitive Impairment by Modified STEADI Categories Risk for Model 1

Results were unadjusted. Figure counts represent those at risk in each modified STEADI category.

Combined Dementia is a combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washington University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1,2, or 3). Clock draw test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Supplementary Figure 2. 1- KM Curve for Cognitive Impairment by Modified STEADI Categories Risk for Model 2

Results were adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age group, race/ethnicity, sex, education). Figure counts represent those at risk in each modified STEADI category.

Combined Dementia is a combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washington University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1,2, or 3). Clock draw test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Supplementary Figure 3. Modified STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries) algorithm for determining participant fall risk.

Key Points

Older adults with an increased fall risk have a higher risk of developing future cognitive decline.

The STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries) fall risk algorithm can possibly predict the risk for future cognitive impairment in older adults in addition to determining fall risk.

Reduced mobility and cognition are geriatric syndromes both associated with increased functional decline, mortality, and hospitalization.

Why does this matter?

There is a relationship between current fall risk and future cognitive decline. This allows future studies to look at how we can use this relationship to improve screening and inevitably patient outcomes with interventions aimed at improving both syndromes.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

Dr. Crow’s research reported in this publication was supported by The Dartmouth Center for Health and Aging and the Department of Medicine.

Dr. Lohman receives funding from the National Institute on Aging: R21AG064310

Dr. Batsis’ research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG051681 and R01-AG067416.

Research reported in this publication was supported by The Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- CDC

Center for Disease Control

- FTSTS

Five Time Sit To Stand

- MMSE

Mini Mental Status Exam

- MOCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- NHATS

National Health and Aging Trends Study

- STEADI

Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the International Conference of Frailty and Sarcopenia Research March 2020 in Toulouse, France

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

Sponsor Role: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Baydan M, Caliskan H, Balam-Yavuz B, Aksoy S, Boke B. Balance and motor functioning in subjects with different stages of cognitive disorders. Exp Gerontol. November 30 2019:110785. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2019.110785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciesielska N, Sokołowski R, Mazur E, Podhorecka M, Polak-Szabela A, Kędziora-Kornatowska K. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test better suited than the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) detection among people aged over 60? Meta-analysis. Psychiatr Pol. October 31 2016;50(5):1039–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Czy test Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) może być skuteczniejszy od powszechnie stosowanego Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) w wykrywaniu łagodnych zaburzeń funkcji poznawczych u osób po 60. roku życia? Metaanaliza. doi: 10.12740/pp/45368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, Horgan F, Fahey T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. February 1 2014;14:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens JA, Phelan EA. Development of STEADI: a fall prevention resource for health care providers. Health Promot Pract. September 2013;14(5):706–14. doi: 10.1177/1524839912463576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coelho FG, Stella F, de Andrade LP, et al. Gait and risk of falls associated with frontal cognitive functions at different stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. September 2012;19(5):644–56. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2012.661398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Motor dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. December 2006;63(12):1763–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waite LM, Grayson DA, Piguet O, Creasey H, Bennett HP, Broe GA. Gait slowing as a predictor of incident dementia: 6-year longitudinal data from the Sydney Older Persons Study. J Neurol Sci. March 15 2005;229–230:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montero-Odasso M, Almeida QJ, Bherer L, et al. Consensus on Shared Measures of Mobility and Cognition: From the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. May 16 2019;74(6):897–909. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacour M, Bernard-Demanze L, Dumitrescu M. Posture control, aging, and attention resources: models and posture-analysis methods. Neurophysiol Clin. December 2008;38(6):411–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wollesen B, Schulz S, Seydell L, Delbaere K. Does dual task training improve walking performance of older adults with concern of falling? BMC Geriatr. September 11 2017;17(1):213. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0610-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modarresi S, Divine A, Grahn JA, Overend TJ, Hunter SW. Gait parameters and characteristics associated with increased risk of falls in people with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. December 6 2018:1–17. doi: 10.1017/s1041610218001783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang C. Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. August 2009;64(8):896–901. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquis S, Moore MM, Howieson DB, et al. Independent predictors of cognitive decline in healthy elderly persons. Arch Neurol. April 2002;59(4):601–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.4.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Savica R, et al. Assessing the temporal relationship between cognition and gait: slow gait predicts cognitive decline in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. August 2013;68(8):929–37. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer's dementia. N Engl J Med. November 28 2002;347(22):1761–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crow RS, Lohman MC, Titus AJ, et al. Mortality Risk Along the Frailty Spectrum: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 to 2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. March 2018;66(3):496–502. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohman MC, Crow RS, DiMilia PR, Nicklett EJ, Bruce ML, Batsis JA. Operationalisation and validation of the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) fall risk algorithm in a nationally representative sample. J Epidemiol Community Health. December 2017;71(12):1191–1197. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. NHATS Technical Paper #2. 2012;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. Findings from the 1st round of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS): introduction to a special issue. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. November 2014;69 Suppl 1:S1–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, Marchetti GF, Gee MA, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: validity of data for the Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test. Phys Ther. October 2005;85(10):1034–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buatois S, Miljkovic D, Manckoundia P, et al. Five times sit to stand test is a predictor of recurrent falls in healthy community-living subjects aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. August 2008;56(8):1575–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01777.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeney T, Fox AB, Jette DU, Jette A. Functional Trajectories of Persons with Cardiovascular Disease in Late Life. J Am Geriatr Soc. January 2019;67(1):37–42. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valluru G, Yudin J, Patterson CL, et al. Integrated Home- and Community-Based Services Improve Community Survival Among Independence at Home Medicare Beneficiaries Without Increasing Medicaid Costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. July 2019;67(7):1495–1501. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verghese J, Ayers E, Barzilai N, et al. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: Multicenter incidence study. Neurology. December 9 2014;83(24):2278–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buracchio T, Dodge HH, Howieson D, Wasserman D, Kaye J. The trajectory of gait speed preceding mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. August 2010;67(8):980–6. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huijben B, van Schooten KS, van Dieën JH, Pijnappels M. The effect of walking speed on quality of gait in older adults. Gait Posture. September 2018;65:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trivedi D Cochrane Review Summary: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Prim Health Care Res Dev. November 2017;18(6):527–528. doi: 10.1017/s1463423617000202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Andrieu S, et al. Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. J Nutr Health Aging. December 2009;13(10):881–9. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0246-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cocchini G, Della Sala S, Logie RH, Pagani R, Sacco L, Spinnler H. Dual task effects of walking when talking in Alzheimer's disease. Rev Neurol (Paris). January 2004;160(1):74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheridan PL, Solomont J, Kowall N, Hausdorff JM. Influence of executive function on locomotor function: divided attention increases gait variability in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. November 2003;51(11):1633–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu-Ambrose T, Ahamed Y, Graf P, Feldman F, Robinovitch SN. Older fallers with poor working memory overestimate their postural limits. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. July 2008;89(7):1335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stuss DT, Alexander MP. Executive functions and the frontal lobes: a conceptual view. Psychol Res. 2000;63(3-4):289–98. doi: 10.1007/s004269900007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galet C, Zhou Y, Eyck PT, Romanowski KS. Fall injuries, associated deaths, and 30-day readmission for subsequent falls are increasing in the elderly US population: a query of the WHO mortality database and National Readmission Database from 2010 to 2014. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1627–1637. doi: 10.2147/clep.S181138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell MA, Hill KD, Blackberry I, Day LL, Dharmage SC. Falls risk and functional decline in older fallers discharged directly from emergency departments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. October 2006;61(10):1090–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fogg C, Meredith P, Bridges J, Gould GP, Griffiths P. The relationship between cognitive impairment, mortality and discharge characteristics in a large cohort of older adults with unscheduled admissions to an acute hospital: a retrospective observational study. Age Ageing. September 1 2017;46(5):794–801. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allali G, Verghese J. Management of Gait Changes and Fall Risk in MCI and Dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. September 2017;19(9):29. doi: 10.1007/s11940-017-0466-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sungkarat S, Boripuntakul S, Chattipakorn N, Watcharasaksilp K, Lord SR. Effects of Tai Chi on Cognition and Fall Risk in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. April 2017;65(4):721–727. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huston P, McFarlane B. Health benefits of tai chi: What is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. November 2016;62(11):881–890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wayne PM, Walsh JN, Taylor-Piliae RE, et al. Effect of tai chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. January 2014;62(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brum PS, Forlenza OV, Yassuda MS. Cognitive training in older adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: Impact on cognitive and functional performance. Dement Neuropsychol. Apr-Jun 2009;3(2):124–131. doi: 10.1590/s1980-57642009dn30200010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montero-Odasso M, Speechley M. Falls in Cognitively Impaired Older Adults: Implications for Risk Assessment And Prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. February 2018;66(2):367–375. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen HH, Sun FJ, Yeh TL, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the Ascertain Dementia 8 questionnaire for detecting cognitive impairment in primary care in the community, clinics and hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. May 23 2018;35(3):239–246. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Morris JC. Evaluation of cognitive impairment in older adults: combining brief informant and performance measures. Arch Neurol. May 2007;64(5):718–24. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol. August 1 2005;162(3):267–78. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. 1- KM Curve for Cognitive Impairment by Modified STEADI Categories Risk for Model 1

Results were unadjusted. Figure counts represent those at risk in each modified STEADI category.

Combined Dementia is a combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washington University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1,2, or 3). Clock draw test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Supplementary Figure 2. 1- KM Curve for Cognitive Impairment by Modified STEADI Categories Risk for Model 2

Results were adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age group, race/ethnicity, sex, education). Figure counts represent those at risk in each modified STEADI category.

Combined Dementia is a combination of Alzheimer’s Disease-8 score or Washington University Dementia Screening Test (AD8) + 3 domains (memory, orientation, executive). Each individual domain binarized based on NHATS cutoffs (0 = not impaired, 1 = impaired). If AD8 score not present, individual domain scores summed – dementia defined as impairment in any domain (summed score 1,2, or 3). Clock draw test; Memory domain (immediate word recall, delayed word recall). Orientation consists of date recall and president/vice president naming.

Fall risk defined by the modified version of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries (STEADI) initiative, Preventing Falls in Older Patients-A Provider Tool Kit.

Supplementary Figure 3. Modified STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries) algorithm for determining participant fall risk.