Abstract

Background

The major complication of COVID-19 is hypoxaemic respiratory failure from capillary leak and alveolar oedema. Experimental and early clinical data suggest that the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor imatinib reverses pulmonary capillary leak.

Methods

This randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial was done at 13 academic and non-academic teaching hospitals in the Netherlands. Hospitalised patients (aged ≥18 years) with COVID-19, as confirmed by an RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, requiring supplemental oxygen to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation of greater than 94% were eligible. Patients were excluded if they had severe pre-existing pulmonary disease, had pre-existing heart failure, had undergone active treatment of a haematological or non-haematological malignancy in the previous 12 months, had cytopenia, or were receiving concomitant treatment with medication known to strongly interact with imatinib. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either oral imatinib, given as a loading dose of 800 mg on day 0 followed by 400 mg daily on days 1–9, or placebo. Randomisation was done with a computer-based clinical data management platform with variable block sizes (containing two, four, or six patients), stratified by study site. The primary outcome was time to discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 consecutive hours, while being alive during a 28-day period. Secondary outcomes included safety, mortality at 28 days, and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation. All efficacy and safety analyses were done in all randomised patients who had received at least one dose of study medication (modified intention-to-treat population). This study is registered with the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2020–001236–10).

Findings

Between March 31, 2020, and Jan 4, 2021, 805 patients were screened, of whom 400 were eligible and randomly assigned to the imatinib group (n=204) or the placebo group (n=196). A total of 385 (96%) patients (median age 64 years [IQR 56–73]) received at least one dose of study medication and were included in the modified intention-to-treat population. Time to discontinuation of ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 h was not significantly different between the two groups (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0·95 [95% CI 0·76–1·20]). At day 28, 15 (8%) of 197 patients had died in the imatinib group compared with 27 (14%) of 188 patients in the placebo group (unadjusted HR 0·51 [0·27–0·95]). After adjusting for baseline imbalances between the two groups (sex, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease) the HR for mortality was 0·52 (95% CI 0·26–1·05). The HR for mechanical ventilation in the imatinib group compared with the placebo group was 1·07 (0·63–1·80; p=0·81). The median duration of invasive mechanical ventilation was 7 days (IQR 3–13) in the imatinib group compared with 12 days (6–20) in the placebo group (p=0·0080). 91 (46%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group and 82 (44%) of 188 patients in the placebo group had at least one grade 3 or higher adverse event. The safety evaluation revealed no imatinib-associated adverse events.

Interpretation

The study failed to meet its primary outcome, as imatinib did not reduce the time to discontinuation of ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 consecutive hours in patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen. The observed effects on survival (although attenuated after adjustment for baseline imbalances) and duration of mechanical ventilation suggest that imatinib might confer clinical benefit in hospitalised patients with COVID-19, but further studies are required to validate these findings.

Funding

Amsterdam Medical Center Foundation, Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek/ZonMW, and the European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative 2.

Introduction

A major complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection is hypoxaemic respiratory failure, which is the cause of most hospital admissions, intubations, and deaths due to COVID-19.1 The clinical manifestation of lung involvement in COVID-19 is pneumonitis, often progressing to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Radiological investigations typically reveal extensive bilateral ground glass opacities and consolidations suggestive of diffuse pulmonary oedema. Post-mortem studies have shown that a key feature of COVID-19 is endothelial injury, which is caused by direct infection of pulmonary endothelial cells,2, 3 disruption of the endothelial barrier, and widespread endothelial cell apoptosis.3

Therapeutic strategies that have been evaluated for COVID-19 include antiviral treatment and immunomodulatory drugs. Remdesivir was found to shorten the time to recovery in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 in the ACTT-1 trial,4 but this finding was not replicated in the WHO Solidarity trial.5 Neither study showed a survival benefit from remdesivir. Other antiviral interventions, including (hydroxy)chloroquine,5, 6 interferon,5 and lopinavir–ritonavir,5, 6, 7 have also failed to show clinical benefit. As an alternative to antiviral treatment, and based on the recognition of a marked hyperinflammatory pattern in patients with a poor outcome, other investigators instead aimed to modulate the immune response. Dexamethasone reduced COVID-19 mortality from 24% to 20% in hospitalised patients, and from 40% to 30% in those in the intensive care unit (ICU).8 The most recent data from the Randomised, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP; published in February, 2021) indicates that monoclonal antibody-mediated inhibition of interleukin-6 with tocilizumab or sarilumab also reduces mortality in patients in the ICU.9

Despite the direct contribution of alveolar oedema to hypoxaemia and adverse outcomes in COVID-19, such as intubation or death, treatment strategies attenuating or reversing this type of lung damage have so far not been evaluated. One of the suggested approaches to attenuate or reverse lung damage is treatment with the antineoplastic drug imatinib.1 The ABL tyrosine-kinase inhibitor imatinib protects against capillary leak and alveolar oedema caused by inflammatory stimuli. Since the first observation of a patient recovering from respiratory failure due to pulmonary veno-occlusive disease following imatinib treatment in 2008,10 in-vitro and in-vivo studies have revealed that imatinib protects the endothelial barrier under inflammatory conditions.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Subsequent case reports verified the protective effect of imatinib in other conditions characterised by alveolar oedema,16, 17, 18 including COVID-19.19

In this report, we aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of oral imatinib in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen administration.

Methods

Study design and patients

This randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial was done at 13 large academic and non-academic teaching hospitals in the Netherlands. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or older, had been admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed with an RT-PCR test), and required supplemental oxygen to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation of greater than 94%. Exclusion criteria included, but were not limited to, pre-existing severe pulmonary disease, pre-existing heart failure (a left ventricular ejection fraction of <40%), active treatment of a haematological or non-haematological malignancy within 12 months before enrolment, the presence of cytopenia, and concomitant treatment with medication known to strongly interact with imatinib. Full details of the exclusion criteria are provided in the study protocol (appendix pp 7–37). Women of childbearing age were asked to undergo a pregnancy test before enrolment.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed on March 5, 2021, using the following search term (“SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“imatinib” OR “Gleevec” OR “Glivec”) AND (“RCT” OR “clinical trial” OR “randomized controlled trial”). We searched for clinical trials assessing the effect of imatinib in patients with COVID-19 published between database inception and March 5, 2021, with no language restrictions. Apart from published trial protocols, no clinical trials were identified. Preclinical studies have shown that imatinib improves endothelial barrier integrity, in particular under inflammatory conditions, and reverses pulmonary oedema in animal models of acute lung injury.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first randomised clinical trial assessing the effects of imatinib in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen. Although other interventions target viral replication (eg, remdesivir) or a dysregulated immune response (eg, corticosteroids or tocilizumab), there are no interventions that target the pulmonary capillary leak and oedema that is observed in patients with COVID-19. This study failed to meet its primary outcome, defined as time to discontinuation of ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 consecutive hours. However, a clinical benefit was suggested by reductions in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation in the imatinib group compared with the placebo group. However, the sample size of the study precludes robust conclusions from the results of these secondary outcomes. Imatinib had a favourable safety profile in this trial.

Implications of all the available evidence

The observed reductions in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation in patients given imatinib compared with placebo suggest that imatinib might benefit patients with COVID-19, particularly those with a severe disease course. Future trials will need to substantiate our findings, both in larger study populations (to allow stratification by disease severity) and in selected patient populations with COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The trial was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC (VUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands), and was done in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before randomisation.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were enrolled by study investigators and randomly assigned (1:1) to either the placebo group or the imatinib group. Randomisation was done with the Castor Electronic Data Capturing System (Castor EDC; Amsterdam, Netherlands) using variable block sizes (two, four, or six patients), stratified by study site. Allocation to study groups was done by Castor, and was not accessible to study investigators. After randomisation, patients received oral imatinib (as 400 mg tablets) or non-identical placebo tablets, which were dispensed by the hospital pharmacy and distributed in sealed containers. Medical staff and investigators were not involved in the dispensing of the study drugs. Patients, medical staff, and investigators were masked to group assignment.

Procedures

After randomisation, patients in the imatinib group received a loading dose of 800 mg imatinib on day 0, followed by 400 mg once daily on days 1–9. Patients in the placebo group received placebo tablets in a similar dosing scheme.

For evaluation of efficacy, the clinical status of patients (ie, whether they had been discharged, admitted to a hospital ward, admitted to the ICU, or had died) and whether they were receiving ventilatory or oxygen support (ie, receiving oxygen supplementation, high-flow nasal oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) were recorded daily on days 0–9 and on day 28. If patients were discharged from the hospital before day 9, their clinical status was ascertained by a telephone call on days 9 and 28.

Safety evaluations included clinical laboratory testing at baseline (day 0) and on days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9, consisting of a blood cell count, and assessment of electrolytes, renal function, and liver enzymes. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was used to monitor corrected QT (QTc) intervals at baseline and on days 1, 3, 5, and 9. Stopping criteria included a reduction in haemoglobin of more than 30% relative to the baseline measurement before the loading dose was given; an absolute leukocyte count of less than 2·5 × 109 cells per L; an absolute thrombocyte count of less than 100 × 109 cells per L; an increase in aminotransferase concentrations to more than three times the upper limit of normal if aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations were within reference values at baseline, or increased AST and ALT concentrations to more than three times the value at baseline if concentrations were higher than reference values at baseline; an increase in bilirubin concentrations of more than 1·5 times the upper limit of normal if bilirubin concentrations were within the normal range at baseline, or an increase in bilirubin concentrations of more than 1·5 times the baseline value if concentrations were higher than reference values at baseline; or an increase in QTc of more than 100 msec relative to baseline. In patients discharged from hospital before day 9, clinical laboratory testing and ECG measurements were suspended, according to guidelines for imatinib treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in an outpatient setting.20 Adverse events and severe adverse events, graded by use of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (November, 2017), were recorded on a daily basis. All grade 3 or higher adverse events reported at any time during the 28-day study period by the patient or observed by the investigator or the medical staff were recorded. The investigators assessed whether an adverse event was related to treatment, and they consulted medical staff if the potential association was not clear.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the time to discontinuation of ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 consecutive hours, while being alive during a 28-day period after randomisation. Secondary efficacy outcomes were: mortality at 28 days, the number of ICU admissions, the length of ICU admission, the need for mechanical ventilation, the duration of mechanical ventilation, the duration of oxygen supplementation, the duration of hospital admission, and clinical status at day 9 and day 28, as assessed by use of the WHO ordinal scale for clinical improvement (with 1 indicating discharge with full recovery [with no home oxygen use]; 2 indicating discharge without full recovery [with actual home oxygen use]; 3 indicating admission to a non-ICU ward and not receiving supplemental oxygen; 4 indicating admission to a non-ICU hospital ward and receiving supplemental oxygen; 5 indicating admission to a medium care unit [MCU] or an ICU without mechanical ventilation; 6 indicating admission to an MCU or ICU with mechanical ventilation; and 7 indicating death). The number of ventilator-free days was defined as the number of days alive and free from mechanical ventilation. Patients were only considered as free from mechanical ventilation if they had a successful extubation, defined as being free from mechanical ventilation for at least 48 consecutive hours. Non-survivors were considered to have no ventilator-free days.

Secondary safety outcomes were incidence of grade 3 and 4 adverse and severe adverse events, blood cell count, kidney function, liver enzymes, N-terminal-pro-B natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP) concentrations (all measured on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9), and QTc intervals (measured on days 0, 1, 3, 5, and 9). Pharmacokinetic and biomarker analyses, as defined in the study protocol, are currently being done and the results will be published separately.

Statistical analysis

Based on an anticipated hazard ratio (HR) of 1·39 for the primary outcome (imatinib group vs the placebo group), a one-sided α level of 0·025 for superiority of the intervention and a β level of 0·20, the sample size was set at 193 patients per group. Analyses for primary and secondary outcomes were done in all patients who underwent randomisation and had received at least one dose of study medication (the modified intention-to-treat population). All statistical analyses were predefined in the study protocol and the statistical analysis plan (appendix pp 38–44). No data were missing for the primary and secondary outcome analyses. No data imputation was done to account for missing data.

Baseline demographic variables are reported as absolute numbers (proportions) for categorical data, or as means (SDs) or medians (IQRs) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were analysed by use of the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were analysed with a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Imbalances at baseline (p<0·10) were carried forward as adjustment factors in regression analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes.

The primary outcome and the secondary outcomes of mortality at day 28 and the need for mechanical ventilation were analysed with Kaplan-Meier curves to plot event rates over time; between-group differences were expressed as HRs with 95% CIs, calculated as regression analyses. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were done for time-to-event analyses of secondary outcomes. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested by examination of Schoenfeld residuals. Two-sided p values are provided for all tests.

All data were recorded in Castor EDC. The Clinical Research Office, an independent contract research organisation of the Amsterdam UMC, was responsible for data monitoring. The safety of patients was monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), which convened after enrolment of 30 patients (April 23, 2020) and 60 patients (May 7, 2020). During these meetings, patient safety was assessed on the basis of an unblinded line listing of severe adverse events. A severe adverse event was defined as any untoward medical event that occurred during the study period that (1) resulted in death; (2) was life-threatening; (3) required inpatient hospitalisation or led to an increased duration of hospitalisation; (4) resulted in persistent or significant disability; or (5) required intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage. The DSMB subsequently convened after enrolment of 100 patients (Oct 22, 2020) and 200 patients (Dec 14, 2020), and patient safety was assessed on the basis of an unblinded line listing of severe adverse events, and futility was assessed on the basis of predefined analyses of efficacy outcomes.

All statistical analyses were done in RStudio, version 1.3.1073. This study is registered with the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2020–001236–10).

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

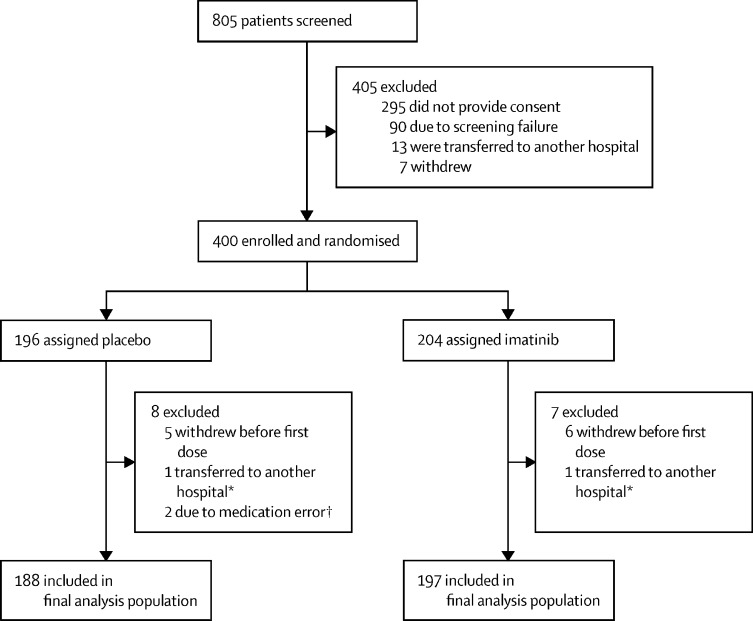

Between March 31, 2020, and Jan 4, 2021, 805 patients at 13 participating hospitals in the Netherlands were screened (appendix p 2). Of these patients, 400 (50%) were enrolled and randomly assigned to the placebo group (n=196) or the imatinib group (n=204). A total of 11 (3%) patients withdrew consent before receiving the first dose of study medication (figure 1 ). During the peaks of the pandemic, two (1%) patients withdrew from the study before receiving their first dose of study medication, as they were relocated to non-participating hospitals with fewer COVID-19 admissions. The final analysis population included 197 patients in the imatinib group and 188 patients in the placebo group (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile

*Patients lost to follow-up due to transfer to another hospital before the first dose of study medication could be administered. †Study medication was dispensed to the wrong patients and they were withdrawn from the study. Errors were detected before the first dose of study medication was given.

The baseline characteristics of patients are shown in table 1 . The median age of patients was 64 years (IQR 56–73; range 28–93). 264 (69%) of 385 patients were men, and the median body-mass index of patients at enrolment was 28·5 kg/m2 (IQR 25·5–32·4). Clinical presentations at baseline included chest pain, dyspnoea, cough, and fever. The median duration from onset of symptoms to randomisation was 10 days (IQR 8–12) in the imatinib group and 10 days (8–12) in the placebo group. Common risk factors for a poor outcome and comorbidities included smoking (153 [40%] of 385 patients), obesity (136 [38%]), diabetes (95 [25%]), cardiovascular disease (83 [22%]), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma (71 [18%]). Despite randomisation, sex, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease were slightly unbalanced between the two groups. No differences in baseline laboratory measurements were observed between the two groups, suggesting similar disease severity at presentation. Medications started at admission included low-molecular-weight heparin, oral anticoagulants, and antibiotics (table 1). Dexamethasone was started at admission in 276 (72%) patients and remdesivir was started in 80 (21%) patients. Most patients (276 [72%] of 385) received dexamethasone on admission to emergency care units before receiving study medication. As participation in other interventional studies was not allowed at enrolment, and because tocilizumab, anakinra, lopinavir–ritonavir, and convalescent plasma were not routinely administered to patients with COVID-19 in the Netherlands at the time the study was done, no patients received these treatments during the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographic variables

| Imatinib group (n=197) | Placebo group (n=188) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 (57–73) | 64 (55–74) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27·5 (25·3–31·1) | 29·7 (25·6–32·9) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 146 (74%) | 118 (63%) | |

| Female | 51 (26%) | 70 (37%) | |

| Comorbidities* | |||

| Current or former smoker | 77 (39%) | 76 (40%) | |

| BMI of >30 kg/m2 | 53 (29%) | 83 (47%) | |

| Diabetes | 41 (21%) | 54 (29%) | |

| Cardiovascular disease† | 35 (18%) | 48 (26%) | |

| Hypertension | 69 (35%) | 76 (40%) | |

| COPD or asthma | 38 (19%) | 33 (18%) | |

| Venous thromboembolism | 5 (3%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Renal failure | 7 (4%) | 7 (4%) | |

| Hepatic disease | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Rheumatic disease | 11 (6%) | 18 (10%) | |

| Heart failure | 8 (4%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Medical treatments‡ | |||

| Glucose lowering drugs | 40 (20%) | 54 (29%) | |

| Antihypertensive treatment | 91 (46%) | 102 (54%) | |

| ACE or ARB | 51 (26%) | 70 (37%) | |

| Statins | 62 (32%) | 65 (35%) | |

| Platelet inhibitors | 42 (21%) | 40 (21%) | |

| Oral anticoagulants | 17 (9%) | 21 (11%) | |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Atypical | 24 (12%) | 32 (17%) | |

| Chest pain | 34 (17%) | 27 (14%) | |

| Cough | 151 (77%) | 141 (75%) | |

| Dyspnoea | 160 (81%) | 158 (84%) | |

| Fever | 133 (68%) | 112 (60%) | |

| Other flu-like symptoms | 82 (42%) | 78 (42%) | |

| Time from symptom onset to randomisation, days | 10 (8–12) | 10 (8–12) | |

| SpO2/FiO2ratio | 321 (265–380) | 323 (238–377) | |

| Laboratory values at admission | |||

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 13·5 (12·6–14·7) | 13·7 (12·6–14·7) | |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 102 (48–158) | 95 (45-149) | |

| NTproBNP, ng/L | 147 (49–411) | 132 (50–352) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 365 (279–445) | 366 (293–496) | |

| Lymphocytes, × 109 cells per L | 0·90 (0·60–1·19) | 0·94 (0·68–1·28) | |

| Neutrophils, × 109 cells per L | 6·00 (4·10–8·56) | 5·94 (4·40–8·29) | |

| Leukocytes, × 109 cells per L | 7·60 (5·60–10·40) | 7·60 (5·77–10·00) | |

| Thrombocytes, × 109 cells per L | 248 (184–323) | 236 (190–310) | |

| Medication initiated at admission | |||

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 167 (85%) | 150 (80%) | |

| Oral anticoagulants | 6 (3%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Antibiotics | 85 (43%) | 77 (41%) | |

| Dexamethasone | 143 (73%) | 133 (71%) | |

| Remdesivir | 40 (20%) | 40 (21%) | |

| (Hydroxy)chloroquine | 15 (8%) | 17 (9%) | |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%). BMI=body-mass index. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme. ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker. SpO2=oxygen saturation. FiO2=fractional concentration of oxygen in inspired air. NTproBNP=N-terminal-pro-B natriuretic peptide.

Comorbidities as reported at admission or present in the patient's medical record.

Cardiovascular diseases included arrythmias (predominantly atrial fibrillation), valvular disease, coronary artery disease, and conduction disorders.

Medical treatment (or home medication) as reported at admission or present in the patient's medical record.

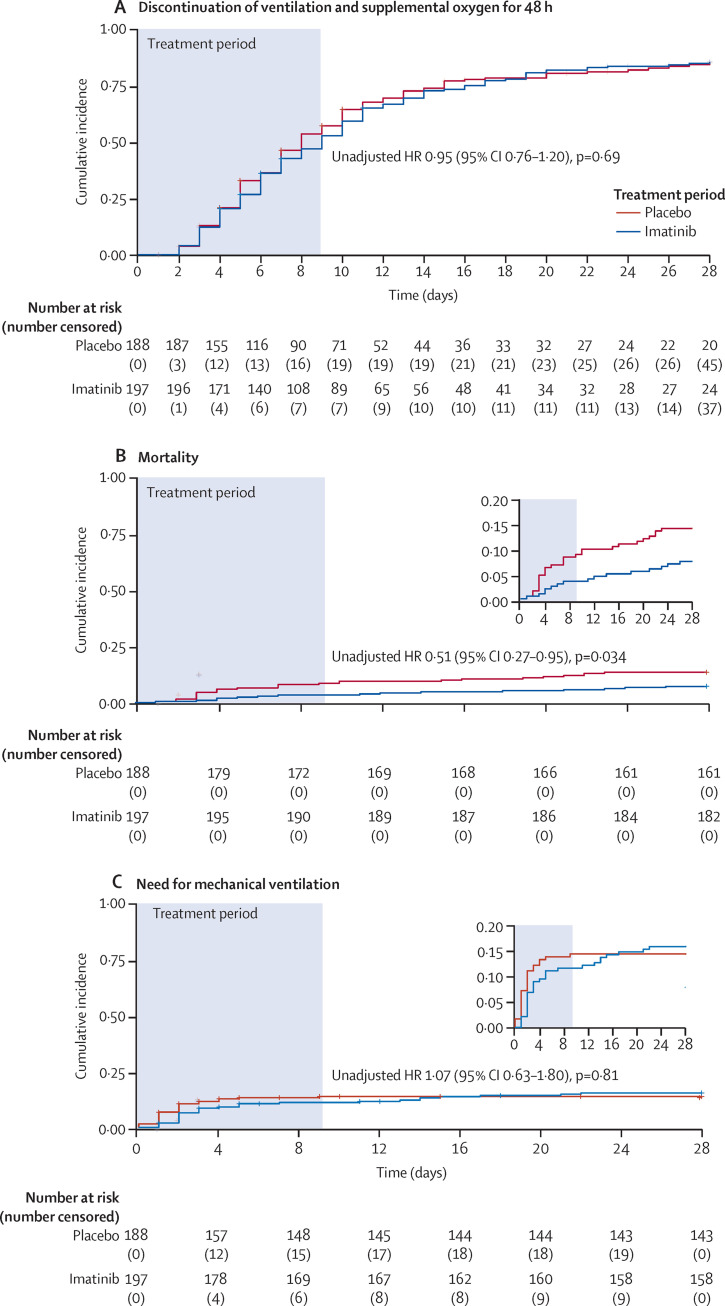

During the 28-day study period, 303 (79%) patients discontinued supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation for more than 48 consecutive hours, including 160 (81%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group and 143 (76%) of 188 patients in the placebo group. For the primary outcome, time to discontinuation of supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation was not significantly different between the two groups (unadjusted HR 0·95 [95% CI 0·76–1·20], p=0·69; figure 2A ). This difference remained non-significant after adjusting for each baseline imbalance (sex, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease) separately and combined (table 2 ).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of primary and secondary outcomes

Kaplan-Meier curves showing time-to-event analyses for time to discontinuation of ventilation and supplemental oxygen for more than 48 consecutive hours, while being alive during the 28-day study period as the primary outcome (A), mortality at 28 days as a secondary outcome (B), and time to invasive mechanical ventilation during the 28-day study period as a secondary outcome (C). Unadjusted HRs with 95% CIs were calculated by Cox regression analyses. HR=hazard ratio.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes in the final analysis population

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||

| Unadjusted | 0·95 (0·76–1·20) | 0·69 |

| Adjusted for sex | 1·01 (0·81–1·28) | 0·90 |

| Adjusted for obesity | 0·99 (0·78–1·26) | 0·92 |

| Adjusted for diabetes | 0·96 (0·76–1·20) | 0·69 |

| Adjusted for cardiovascular disease | 0·94 (0·75–1·18) | 0·59 |

| Adjusted for all the above | 1·07 (0·62–1·84) | 0·82 |

| Mortality (secondary endpoint) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0·51 (0·27–0·95) | 0·034 |

| Adjusted for sex | 0·47 (0·25–0·89) | 0·019 |

| Adjusted for obesity | 0·46 (0·23–0·92) | 0·029 |

| Adjusted for diabetes | 0·54 (0·29–1·02) | 0·057 |

| Adjusted for cardiovascular disease | 0·54 (0·29–1·01) | 0·055 |

| Adjusted for all the above | 0·52 (0·26–1·05) | 0·068 |

| Need for mechanical ventilation (secondary endpoint) | ||

| Unadjusted | 1·07 (0·63–1·80) | 0·81 |

| Adjusted for sex | 0·98 (0·58–1·67) | 0·95 |

| Adjusted for obesity | 1·08 (0·63–1·86) | 0·77 |

| Adjusted for diabetes | 1·13 (0·66–1·91) | 0·66 |

| Adjusted for cardiovascular disease | 1·06 (0·62–1·79) | 0·84 |

| Adjusted for all the above | 1·02 (0·80–1·30) | 0·87 |

All HRs are for the imatinib group versus the placebo group. The final analysis population consisted of 188 patients in the placebo group and 197 patients in the imatinib group. HRs and 95% CIs were calculated by use of Cox regression analysis and adjusted for sex and the indicated comorbidities. HR=hazard ratio.

The Kaplan-Meier curves for mortality are shown in figure 2B. At day 28, 15 (8%) of 197 patients had died in the imatinib group compared with 27 (14%) of 188 patients in the placebo group. The unadjusted HR for mortality in the imatinib group versus the placebo group was 0·51 (95% CI 0·27–0·95; p=0·034). The HRs for mortality were attenuated, and for some of the adjusted analyses became non-significant after adjusting for imbalances in the baseline characteristics (table 2), as the number of men outnumbered the number of women in the imatinib group, and a higher proportion of patients in the placebo group had diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or both than in the imatinib group. After adjusting for all imbalances, the HR for mortality was 0·52 (95% CI 0·26–1·05; p=0·068; table 2). Logistic regression analysis yielded an odds ratio for mortality at 28 days in the imatinib group versus the placebo group of 0·49 (95% CI 0·25–0·96).

During the 28-day study period, 39 (20%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group and 33 (18%) of 188 patients in the placebo group were admitted to the ICU. Patients in the ICU in the two treatment groups were balanced in terms of baseline characteristics (data not shown). Of these patients, 30 (77%) in the imatinib group and 26 (79%) in the placebo group were intubated and mechanically ventilated (figure 2C). The unadjusted HR for mechanical ventilation in the imatinib group versus the placebo group was 1·07 (95% CI 0·63–1·80; p=0·814; figure 2C, table 2), and this difference between the groups remained insignificant when adjusting for sex, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (figure 2C, table 2). The median duration of mechanical ventilation was 7 days (IQR 3–13) in the imatinib group and 12 days (6–20) in the placebo group (p=0·0080; table 3 ). In post-hoc analyses, we restricted the analysis to survivors only, and observed that the median duration of mechanical ventilation in the imatinib group was 7 days (3–12) compared with 12 days (6–25) in the placebo group (p=0·023). In patients admitted to the ICU, the number of ventilator-free days was 22 (14–26) in the imatinib group versus 9 days (0–23) in the placebo group (p=0·018; table 3).

Table 3.

Duration of respiratory support and care in the final analysis population

| Imatinib group (n=197) | Placebo group (n=188) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of oxygen supplementation, days | 7 (3–12) | 5 (3–11) | 0·23 | |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | ||||

| Final analysis population* | 7 (3–13) | 12 (6–20) | 0·0080 | |

| Survivors† | 7 (3–12) | 12 (6–25) | 0·023 | |

| Duration of intensive care unit admission, days‡ | 8 (5–13) | 15 (7–21) | 0·025 | |

| Number of ventilator-free days in the ICU population§ | 22 (14–26) | 9 (0–23) | 0·018 | |

| Duration of hospital admission, days | 7 (4–11) | 6 (3–11) | 0·51 | |

Data are median (IQR).

Measured in 30 (15%) participants in the imatinib group and 26 (14%) patients in the placebo group.

Measured in 24 (12%) patients in the imatinib group and 18 (10%) patients in the placebo group.

Measured in 39 (20%) patients in the imatinib group and 33 (18%) patients in the placebo group.

Measured in 39 (20%) patients in the imatinib group and 33 (18%) patients in the placebo group.

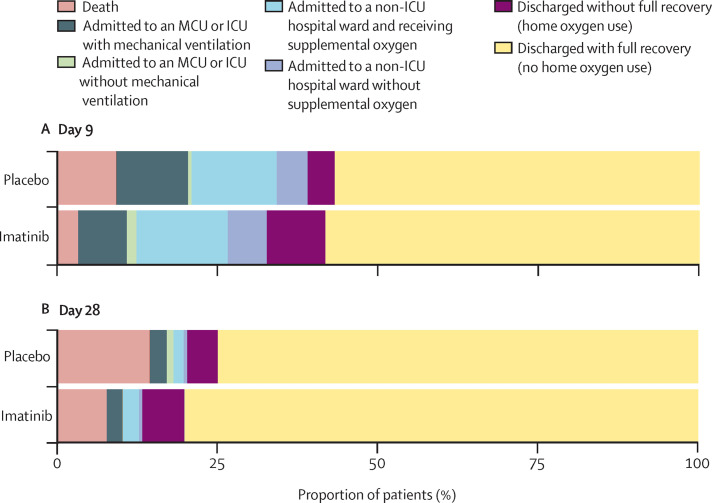

The median duration of hospital admission was 7 days (IQR 4–11) in the imatinib group and 6 days (3–11) in the placebo group (p=0·51). The median duration of oxygen supplementation was 7 days (3–12) in the imatinib group and 5 days (3–11) in the placebo group (p=0·23; table 3). The median duration of ICU stay was 8 days (5–13) in the imatinib group and 15 days (7–21) in the placebo group (p=0·025). The proportions of patients at different stages of clinical recovery, classified as per the WHO ordinal scale for clinical recovery, at day 9 and day 28 of the study period are shown in figure 3 . Compared with placebo, imatinib use was associated with fewer patients classified as having high disease severity on day 9 and day 28 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clinical status at day 9 (A) and day 28 (B)

Classification of patients in the imatinib group versus the placebo group according to the WHO seven-point ordinal scale for clinical improvement at day 9 and day 28 of the study period. MCU=medium care unit. ICU=intensive care unit.

Of all 385 patients, 231 (60%) received the complete 10-day course of study medication; 77 (38%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group and 77 (41%) of 188 patients in the placebo group did not receive the complete course of study medication. The mean duration of study drug use was 7·6 days (SD 3·4) in the imatinib group and 7·7 days (3·2) in the placebo group. Frequent reasons for not completing the full course included requesting to stop treatment (44 [11%] of 385 patients), discontinuation due to discharge or transfer to another hospital (37 [10%]), and discontinuation based on stopping criteria (34 [9%]). 30 (15%) patients in the imatinib group and 14 (7%) patients in the placebo group requested to discontinue the study medication (appendix p 5). The most frequent reasons for discontinuation of study medication reported by patients included grade 1 or 2 gastrointestinal discomfort (appendix p 6). 11 (6%) patients in the imatinib group and 23 (12%) patients in the placebo group discontinued treatment because they met predefined stopping criteria (appendix p 5).

Test results for kidney function, liver and cardiac enzymes, and QTc intervals on days 0–5 are provided in the appendix (pp 3–4). Creatinine concentrations on day 1 were slightly higher in the imatinib group than in the placebo group, but no differences were observed on subsequent days. Additionally, no differences in liver enzymes, NTproBNP concentrations, or QTc intervals were observed between the two groups.

During the study, grade 3, 4, and 5 adverse events were recorded. A total of 188 grade 3 or 4 adverse events were reported in patients in the imatinib group and 260 events were reported in the placebo group. 91 (46%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group and 82 (44%) of 188 patients in the placebo group had at least one grade 3 or higher adverse event. The most frequent grade 3 adverse events included thromboembolic events, decreased lymphocyte counts, alkalosis, and hyperglycaemia (table 4 ). The most frequent grade 4 adverse event was ARDS. No specific adverse events were attributed to imatinib treatment. Two (1%) patients in the placebo group had acute renal failure compared with none of the patients in the imatinib group. Most grade 5 adverse events were ARDS, which occurred in 12 (6%) patients in the imatinib group and in 35 (12%) patients in the placebo group (appendix p 6). Haemorrhagic stroke was observed in one (1%) patient in the imatinib group and in one (1%) patient in the placebo group, both of which occurred after extended anticoagulation treatment for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 4.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events in the modified intention-to-treat population

|

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imatinib group (n=197) | Placebo group (n=188) | Total (n=385) | Imatinib group (n=197) | Placebo group (n=188) | Total (n=385) | ||

| Any adverse event | 156 (79%) | 218 (116%) | 374 (97%) | 32 (16%) | 42 (22%) | 74 (19%) | |

| Anaemia | 3 (2%) | 7 (4%) | 10 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cardiac disorders | |||||||

| Atrioventricular block complete | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rhythm disorder (atrial fibrillation or flutter) | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Sinus bradycardia | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Myringitis with bloody otorrhoea | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Adrenal insufficiency | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eye disorders | |||||||

| Conjunctivitis | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%)* | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||||

| Diarrhoea | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ileus | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rectal haemorrhage | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Vomiting | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gastric ulcer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | |||||||

| Fever | 1 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (1%) | ||||

| Multiorgan failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Infections and infestations | |||||||

| Lip infection | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lung infection (other than COVID-19) | 7 (4%) | 10 (5%) | 17 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other† | 5 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sepsis | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Investigations | |||||||

| Increased blood ALT or AST | 6 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 11 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased blood creatinine | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased blood γ-glutamyl transferase | 0 | 3 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prolonged QT corrected interval | 8 (4%) | 14 (7%) | 22 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased lymphocyte count | 20 (10%) | 15 (8%) | 35 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Decreased white blood cell count | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Increased creatinine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Decreased platelet count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | |||||||

| Acidosis | 10 (5%) | 8 (4%) | 18 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (3%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Alkalosis | 21 (11%) | 20 (11%) | 41 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anorexia | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hyperglycaemia | 22 (11%) | 37 (20%) | 59 (15%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hyperkalaemia | 1 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypernatremia | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2 (1%) | 5 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypokalaemia | 2 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

| Hyponatremia | 1 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Benign, malignant, or unspecified neoplasm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%)‡ | 1 (<1%) | |

| Nervous system disorders | |||||||

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ischaemic stroke | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Delirium | 2 (1%) | 12 (6%) | 14 (4%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Renal and urinary disorders | |||||||

| Haematuria | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | |||||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 9 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 26 (13%) | 20 (11%) | 46 (12%) | |

| Pneumothorax | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other§ | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 6 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

| Aspiration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||||||

| Maculopapular rash | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (1%)¶ | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vascular disorders | |||||||

| Hypotension | 1 (1%) | 7 (4%) | 8 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| Thromboembolic event | 18 (9%) | 14 (7%) | 32 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | |

The severity of adverse events was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0. All patients who received at least one dose of study medication were included in the safety population. ALT=alanine aminotransferase. AST=aspartate aminotransferase.

Patient developed a conjunctivitis with a haematoma in both eyes. The patient was unmasked and treatment was discontinued; symptoms resolved shortly thereafter.

Defined as a positive throat swab culture that resulted in starting intravenous antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral treatment.

Patient was diagnosed with a malignancy.

Six patients were readmitted to the hospital ward: four due to complaints of dyspnoea, one due to pneumonia unrelated to COVID-19, and one due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Patient was diagnosed with a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, confirmed by skin biopsy.

Discussion

Treatment of hospitalised, hypoxaemic patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis with imatinib did not change the time to discontinuation of supplemental oxygen and ventilation when compared with placebo (primary outcome). However, the analysis of secondary outcomes indicated that mortality at 28 days was lower in the imatinib group than in the placebo group, which paralleled reductions in the duration of mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay. Of note, the statistical significance of the change in mortality was somewhat attenuated after adjustment for baseline imbalances. In terms of safety, no imatinib-related adverse events (grade 3 or higher) were observed.

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to evaluate imatinib in patients with COVID-19. The rationale behind the use of imatinib treatment was to mitigate pulmonary capillary leak and alveolar oedema in these patients, as experimental and early clinical evidence suggests that imatinib protects the integrity of the vascular barrier in a wide array of inflammatory conditions.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Contrary to our expectations, and despite reductions in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation, imatinib did not reduce the time to discontinuation of respiratory support, as measured by the combined endpoint of use of supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation. This primary outcome was chosen on the premise that imatinib would accelerate recovery in all patients. Of all 385 patients included in the final analysis, 303 (79%) discontinued supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation for more than 48 consecutive hours, indicating a mild disease course in most patients. Although this study does not provide evidence of clinical benefit in patients with a mild disease course, our data do suggest that imatinib might confer benefit specifically in patients with severe COVID-19. Imatinib did not prevent the need for mechanical ventilation, but did reduce its duration. These findings suggest that imatinib might have altered the disease course, specifically in patients with severe COVID-19; from critically ill to a less severe state of disease, with a long-term need for oxygen supplementation. Independent validation of this clinical benefit from imatinib in patients with severe forms of COVID-19 is required. Trials of oral imatinib in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 are currently recruiting patients in Spain (NCT04346147) and in the USA (NCT04394416).

Although the rationale behind imatinib treatment was to mitigate pulmonary capillary leak, the question of why clinical benefit was predominantly observed in patients with COVID-19-associated ARDS remains. One explanation might be that the relative contribution of pulmonary capillary leak is larger in patients with COVID-19-associated ARDS than in less severe forms of COVID-19. This hypothesis is supported by plasma studies, which have linked circulating markers of vascular injury, such as angiopoietin-2, von Willebrand factor, and E-selectin, to clinical severity in patients with COVID-19.21 Concentrations of circulating angiopoietin-2 and E-selectin were higher in patients requiring ICU admission,22 and high concentrations at presentation23 or increasing concentrations during admission were predictors of mortality.24 Similar findings were observed in patients with ARDS unrelated to COVID-19, in which increasing concentrations of angiopoietin-2 and von Willebrand factor were associated with pulmonary vascular leak and increased ARDS severity.25 The results of these biomarker studies together with our clinical observations could indicate that pulmonary capillary leak underlies the transition to a clinical ARDS phenotype, which can be targeted by imatinib. Alternatively, imatinib could target pathways other than alveolocapillary integrity. Imatinib exerts a vasculoprotective effect via inhibition of the ABL2 tyrosine kinase.12, 26 ABL2 is an important regulator of the cytoskeleton, and, as such, has also been shown to mediate endosomal trafficking of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viral particles.27 Imatinib has shown antiviral activity against SARS-CoV27 and SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.28 However, another study found no evidence that viral replication or cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 was inhibited at clinically achievable concentrations.29 Whether there are direct antiviral effects of ABL tyrosine-kinase inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 therefore remains controversial.

This trial has some limitations. First, 14 (7%) of 188 patients in the placebo group and nine (5%) of 197 patients in the imatinib group were lost to follow-up or withdrew consent between randomisation and the first dose of study medication. This attrition was partly explained by the fact that, during the pandemic, high numbers of admissions in particular regions in the Netherlands forced hospitals to relocate their patients to hospitals in other regions. Second, despite randomisation, there were imbalances in several baseline variables between the two groups (including sex and comorbidities). We corrected for these imbalances by calculating adjusted HRs. Third, hospital discharge policies changed over the course of the pandemic, with early home or nursing home discharge on continued oxygen treatment30 only possible from the second half of the year. These policy changes could have affected measurement of the primary outcome. Fourth, although a significant difference in mortality at 28 days was observed between the imatinib group and the placebo group, the study was not powered to detect significant differences in mortality, precluding robust conclusions from these analyses. Adjustment for baseline imbalances also yielded a non-significant result; however, the HR for mortality at 28 days remained mostly unchanged, indicating that it shows little residual confounding. Finally, the study period of 28 days might be short relative to other trials of treatments for COVID-19, given the high frequency of readmissions due to COVID-19 and that several patients have an extended recovery period. Follow-up for 3 or 6 months, as has been done in most studies of long-term COVID-19 sequelae, could provide relevant information about the effects of imatinib on the long-term outcomes and functional status of patients.

The major strengths of our trial are its randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind design, and the fact that it was done in a day-to-day health-care setting. All hospitalised patients aged 18 years or older were eligible, including patients aged older than 85 years and patients with a do-not-resuscitate order. In addition, 72% of patients received dexamethasone as a co-treatment, indicating that the possible benefits of imatinib treatment have an additive effect to standard care. Finally, although imatinib was originally developed as an outpatient therapy for chronic myeloid leukaemia,31 this study provides extensive safety data on imatinib in a severe, critically ill population. An extensive safety analysis, which included laboratory and ECG tests, as well extensive adverse event reporting, revealed that imatinib was well tolerated and safe in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19. In fact, only a few adverse events were observed, and no renal, hepatic, or cardiac toxicity was reported.

The observed reductions in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation in patients given imatinib are of direct relevance. First, as our study suggests that imatinib predominantly benefits patients with severe course of COVID-19, future trials are needed in selected patients with COVID-19-associated ARDS or in larger study populations, thus allowing stratification by disease severity. Of note, one trial of intravenous imatinib in patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilation started patient recruitment in March, 2021 (NCT04794088). Second, a treatment period of 10 days, as used in our study, might need to be reconsidered. We based our choice of treatment duration on early observations that respiratory deterioration in COVID-19 occurs within the first 10 days after onset of symptoms.32 Time-to-event analyses, however, showed that the Kaplan-Meier curves for mechanical ventilation in the imatinib and placebo groups crossed after day 9 (figure 2C), which could indicate a catch-up phenomenon after the final day of study medication. The proportional hazards assumption was violated for the secondary outcome of the need for mechanical ventilation. This violation could have resulted in an underestimation of the treatment effect and advocates for increasing the treatment duration.

In conclusion, this randomised, placebo-controlled trial showed that imatinib does not reduce the time to discontinuation of supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. However, the reduction in mortality (even if attenuated after correction for baseline imbalances) and duration of mechanical ventilation indicates that imatinib might confer clinical benefit in patients with COVID-19, and provide a rationale for further studies.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com/respiratory on June 25, 2021

Data sharing

For sharing purposes, reuse conditions will be respected. The deidentified patient data will be accessible after publication of the Article, and can be requested from the corresponding author (hj.bogaard@amsterdamumc.nl) by other researchers if reuse conditions are met.

Declaration of interests

JA and AVN are inventors on a patent (WO2012150857A1; 2011) covering protection against endothelial barrier dysfunction through inhibition of the tyrosine kinase abl-related gene (arg). JA reports serving as a non-compensated scientific advisor for Exvastat. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an unrestricted grant from the Amsterdam Medical Center Foundation and a bottom-up grant from Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek/ZonMW (10430 01 201 0007). In addition, this project received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (grant agreement number 101005142).

Contributors

JA, ED, FSdM, and HJB had full access to and verified the study data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data. JA, LB, AK, LAH, LDJB, ASN, PIB, AVN, and HJB provided input on trial design. All authors were involved in conducting the trial. ED and RJAH were involved in data management. FSdM statistically analysed the data. JA, ED, FSdM, AVN, and HJB were involved in data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, and JA and HJB had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium. Pan H, Peto R, et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19 - interim WHO Solidarity Trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Mafham M, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2030–2040. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.REMAP-CAP Investigators. Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overbeek MJ, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Boonstra A, Smit EF, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Possible role of imatinib in clinical pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:232–235. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Geyer M, et al. Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood-brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2008;14:731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aman J, van Bezu J, Damanafshan A, et al. Effective treatment of edema and endothelial barrier dysfunction with imatinib. Circulation. 2012;126:2728–2738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.134304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chislock EM, Pendergast AM. Abl family kinases regulate endothelial barrier function in vitro and in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letsiou E, Rizzo AN, Sammani S, et al. Differential and opposing effects of imatinib on LPS- and ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L259–L269. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00323.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer V, Vivi E, Regensburger D, et al. IFN-γ drives inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis through VE-cadherin-directed vascular barrier disruption. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4691–4707. doi: 10.1172/JCI124884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carnevale-Schianca F, Gallo S, Rota-Scalabrini D, et al. Complete resolution of life-threatening bleomycin-induced pneumonitis after treatment with imatinib mesylate in a patient with Hodgkin's lymphoma: hope for severe chemotherapy-induced toxicity? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e691–e693. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aman J, Peters MJ, Weenink C, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Vonk Noordegraaf A. Reversal of vascular leak with imatinib. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1171–1173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0136LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langberg MK, Berglund-Nord C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Haugnes HS, Tandstad T, Langberg CW. Imatinib may reduce chemotherapy-induced pneumonitis. A report on four cases from the SWENOTECA. Acta Oncol. 2018;57:1401–1406. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1479072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales-Ortega A, Bernal-Bello D, Llarena-Barroso C, et al. Imatinib for COVID-19: a case report. Clin Immunol. 2020;218 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochhaus A, Saussele S, Rosti G, et al. Chronic myeloid leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv41–iv51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou-Arab O, Bennis Y, Gauthier P, et al. Association between inflammation, angiopoietins, and disease severity in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a prospective study. Br J Anaesth. 2020;126:e127–e130. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smadja DM, Guerin CL, Chocron R, et al. Angiopoietin-2 as a marker of endothelial activation is a good predictor factor for intensive care unit admission of COVID-19 patients. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s10456-020-09730-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vassiliou AG, Keskinidou C, Jahaj E, et al. ICU admission levels of endothelial biomarkers as predictors of mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Cells. 2021;10:186. doi: 10.3390/cells10010186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villa E, Critelli R, Lasagni S, et al. Dynamic angiopoietin-2 assessment predicts survival and chronic course in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5:662–673. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Heijden M, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Koolwijk P, van Hinsbergh VW, Groeneveld AB. Angiopoietin-2, permeability oedema, occurrence and severity of ALI/ARDS in septic and non-septic critically ill patients. Thorax. 2008;63:903–909. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.087387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amado-Azevedo J, van Stalborch AD, Valent ET, et al. Depletion of Arg/Abl2 improves endothelial cell adhesion and prevents vascular leak during inflammation. Angiogenesis. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10456-021-09781-x. published online March 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman CM, Sisk JM, Mingo RM, et al. Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J Virol. 2016;90:8924–8933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01429-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Y, Duan X, Yang L, et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors using lung and colonic organoids. Nature. 2021;589:270–275. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2901-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H, Mendenhall M, Deininger MW. Imatinib is not a potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug. Leukemia. 2020;34:3085–3087. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-01045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap Leidraad zuurstofgebruik THUIS bij (verdenking op / bewezen) COVID-19. April 22, 2020. https://www.nhg.org/sites/default/files/content/nhg_org/uploads/050620_zuurstof_thuis_ten_tijde_van_corona_definitieve_versie_1.1_nvalt-nhg-pznl.pdf

- 31.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For sharing purposes, reuse conditions will be respected. The deidentified patient data will be accessible after publication of the Article, and can be requested from the corresponding author (hj.bogaard@amsterdamumc.nl) by other researchers if reuse conditions are met.