Abstract

Background

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) is a deadly tumor with a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis. Keratin 7 (KRT7) is a member of the keratin gene family that is involved in the regulation of cell growth, migration and apoptosis in many cancers. However, the role of KRT7 and its biological functions in PAAD remain unclear. We systemically analyzed the expression and clinical values of KRT7 in PAAD.

Methods

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA), Oncomine and Human Protein Atlas (HPA) databases were used to analyze the mRNA and protein expression of KRT7 in PAAD. The prognosis and subgroup analysis of KRT7 in PAAD patients was performed using the GEPIA, PROGgeneV2 and UALCAN databases. Later, the correlation between KRT7 expression and tumor immune molecules in PAAD was evaluated using the Immune Cell Abundance Identifier (ImmuCellAI) and TISIDB databases. Finally, the functional enrichment pathway of KRT7 and its coexpressed genes were analyzed by the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) and Metascape databases and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA).

Results

The mRNA and protein expression of KRT7 was increased in PAAD tissues compared with normal tissues. High KRT7 expression was closely associated with tumor grade, TP53 mutations and poor prognosis in PAAD patients. Cox regression analysis proved that overexpressed KRT7 was an important and independent risk factor for poor overall survival (P = 0.006, HR =1.87) and disease-free survival (P = 0.019, HR =1.793) in PAAD. Additionally, KRT7 expression was significantly associated with immune infiltration of tumor immune cells and immunomodulators. Functional enrichment analyses and GSEA indicated that KRT7 might be involved in the regulation of the p53 pathway in PAAD.

Conclusion

Overexpressed KRT7 could be a promising prognostic and therapeutic target biomarker for PAAD by bioinformatics analysis.

Keywords: pancreatic adenocarcinoma, KRT7, prognosis, biomarker, bioinformatics analysis

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) is a deadly malignant tumor with a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis.1 Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, with local or systemic metastases. Only 15%-20% of patients are eligible for surgical resection, but metastasis and recurrence are also prone to occur after surgery.2,3 Despite considerable improvements in surgical techniques and neoadjuvant therapy, in some countries and regions, the five-year survival rate of the disease is still approximately 5%.4 Thus, it is critical to identify novel biomarkers to provide accurate prediction of treatment targets and prognosis for PAAD, which means therapy can be tailored to the individual patient.5

Keratin 7 (KRT7) is a gene encoding type II keratin mainly expressed in simple epithelial cells and their neoplasms. Type I and type II keratins are intermediate-filament-forming proteins expressed in epithelial cells.6 The main roles of keratin include maintaining cell integrity and regulating cell growth, migration and apoptosis in normal tissues and cancer.7 Several studies have identified KRT7 as an immunohistochemical biomarker and overexpressed KRT7 has been considered a poor prognostic factor in many cancers, such as renal neoplasm, lung cancer and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.8–10 Schüssler et al reported that KRT7 was expressed in all pancreatic cancers and could be used to distinguish normal pancreas from pancreatic cancer.11 It was speculated that KRT7 might be a novel promising diagnostic and prognostic indicator for PAAD. To our knowledge, there are no reports investigating the prognostic role of KRT7 and its potential mechanism in PAAD.

The present study comprehensively evaluated the expression and clinical significance of KRT7 in PAAD and its underlying mechanisms by using publicly available databases such as Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA), Oncomine, Human Protein Atlas (HPA), UALCAN and PROGgeneV2. The prognostic value of KRT7 expression was validated by Cox regression analysis. Additionally, the Immune Cell Abundance Identifier (ImmuCellAI) and TISIDB databases were used to assess the relationships among KRT7 expression and tumor infiltrating immune cells and immunomodulators. The coexpressed genes of KRT7 in PAAD were also identified using the LinkedOmics database, and the regulatory network and possible mechanism of these genes were clarified by protein–protein interaction network, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses. Metascape and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) were also used to reveal the biological functions and signaling pathways related to KRT7 in PAAD. In summary, this study comprehensively clarified the prognostic value and underlying mechanism of KRT7 in PAAD by using multidimensional analysis methods.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

The information of PAAD samples was obtained from the public The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/).12 The TCGA-PAAD dataset included RNA-sequencing data and corresponding clinical information of 178 patients. All data were processed and statistically analyzed using R software (version 3.6.1). To explore the effect of KRT7 expression on PAAD, patients were divided into two groups based on the medium value of KRT7 expression. The Wilcoxon test was performed to compare the differences between two groups. The correlations of KRT7 expression with clinicopathological parameters were assessed by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The univariate and multivariate Cox analysis was conducted to validate the prognostic value of KRT7 expression by using Survival package. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analysis of KRT7 Expression in PAAD

GEPIA13 (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) is a powerful online platform that can provide differential expression analysis, correlation analysis, and patient survival analysis based on the data from the TCGA and genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) databases. In this study, the mRNA expression of KRT7 in PAAD and normal pancreas tissues is compared and represented by box plots via the GEPIA database.

The Oncomine database14 (http://www.oncomine.org) provides comprehensive analysis results of multiple cancer transcriptome datasets. We further validated KRT7 expression in tumor and normal samples based on a series of published studies. P value ≤1E-4, fold change ≥2 and top 10% gene rank were selected as thresholds.

The HPA database15 (Human Protein Atlas, https://www.proteinatlas.org) is the largest comprehensive database providing expression data of 1,7058 proteins in cell lines, normal human tissues and tumor tissues through immunodetection techniques. In this study, we used the HPA database to assess the immunohistochemical staining of KRT7 in PAAD.

Survival and Subgroup Analyses

PROGgeneV216 (http://www.compbio.iupui.edu/proggene) is an online database for survival analysis of genes in various cancer types. Users can perform survival analysis on a single gene, multiple genes, ratio of expression of two genes and gene signatures across a large of publicly available microarray datasets. For more rigorous results, the present study explored the relationship of KRT7 expression with overall survival and disease-free survival in PAAD using the GEPIA and PROGgeneV2 databases. Hazard ratio (HR) values and logrank P values were calculated. The expression threshold was set at 50%, and the P value cutoff was 0.05.

UALCAN17 (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) is a web server based on TCGA data that users can analyze the relative expression and prognostic information of certain genes in various tumors. In this study, UALCAN was used to explore the relationship between KRT7 expression and distinct clinicopathological features.

Correlation Analysis Between KRT7 and Immune Features in PAAD

The ImmuCellAI database18 (Immune Cell Abundance Identifier, http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/web/ImmuCellAI/) is a new powerful web portal to estimate the infiltration level of 24 immune cells including 18 T-cell subsets and 6 other critical immune cells based on RNA sequencing and microarray data. The results of flow cytometry demonstrated that ImmuCellAI algorithm can estimate the abundance of immune cells more accurately than other algorithms, such as Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT),19 xCell20 and Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER).21 The immune cells consist of B cells, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells and 18 T-cell subtypes, namely, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, naïve CD4+ T cells, naïve CD8+ T cells, cytotoxic T (Tc) cells, exhausted T (Tex) cells, type 1 regulatory T (Tr1) cells, natural regulatory T (nTreg) cells, induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells, T helper 1, 2, and 17 (Th1, Th2, and Th17) cells, follicular T helper (Tfh) cells, central memory T (Tcm) cells, effector memory T (Tem) cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, and gamma delta T (Tgd) cells. We calculated the abundance of each immune cell type in TCGA-PAAD samples and visualized the results by R software.

TISIDB22 (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) is a comprehensive tool to investigate the interactions between select genes and the immune system in 30 TCGA cancer types. TISIDB was utilized to explore the relationship between KRT7 expression and immunomodulators. The correlation was measured by Spearman’s test and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Analysis of Coexpressed Genes of KRT7 in PAAD

LinkedOmics23 (http://www.linkedomics.org) is an open platform database containing multiomics data and clinical data for 32 TCGA cancer types. In this study, the LinkFinder module helped us analyze the correlation between KRT7 and other genes in PAAD. We identified coexpressed genes that were strongly positively correlated with KRT7 expression with Pearson correlation coefficient >0.7 and P value <0.05 as criteria. These genes coexpressed with KRT7 were then submitted to the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING)24 database (https://string-db.org/) to construct a protein–protein interaction network. Cytoscape25 and its plug-in Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) were utilized to analyze and visualize the most dense and significant module in the PPI network. GO and KEGG enrichment analysis were conducted to reveal the functions and regulatory pathways of these genes in PAAD by using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) database26 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

Functional Enrichment Analysis and GSEA of KRT7

GeneMANIA27 (http://genemania.org) is a useful tool for identifying genes that are functionally similar to specific genes and revealing their functional interaction networks. In the present study, we analyzed the relationship between KRT7 and its interactive genes by using the GeneMANIA database. Then, KRT7 and its interactive genes were input into the Metascape database to assess their biological functions. GSEA28 is a computational method to assess the significant difference of a predetermined set of genes in two different biological states. GSEA software was used to explore the biological functions of KRT7 expression in PAAD. The normalized enrichment score was determined by analyzing 1000 permutations. P value <0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.25 were criteria to identify the significantly enriched gene set.

Results

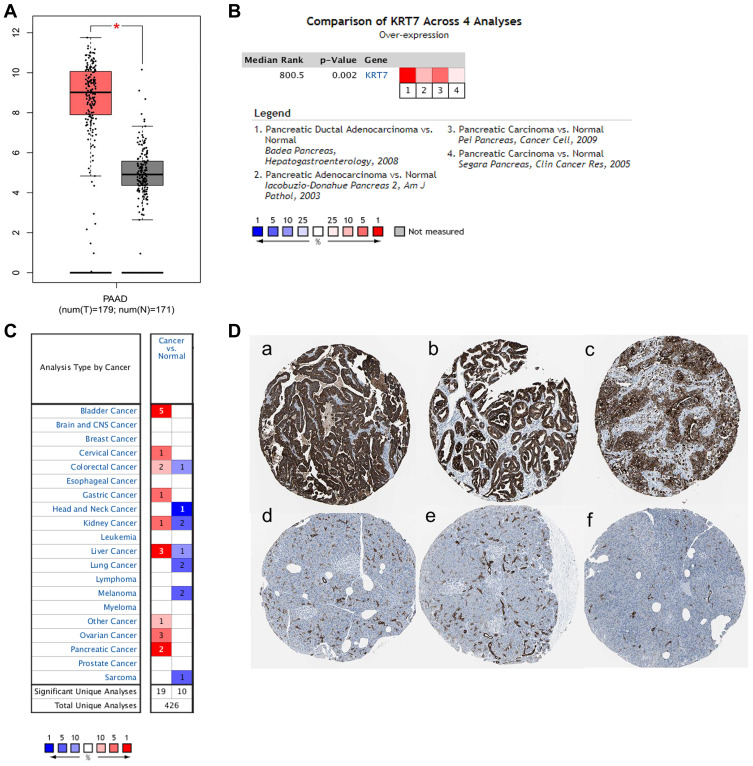

KRT7 Was Upregulated in PAAD

The expression levels of KRT7 in PAAD samples and normal samples were analyzed and compared using the GEPIA, Oncomine and HPA databases. In the GEPIA database, KRT7 was overexpressed in PAAD tissues compared to normal tissues (Figure 1A). This result was further validated by the Oncomine database. Meta-analyses of four studies revealed that the mRNA expression of KRT7 was higher in PAAD samples than in normal samples (Figure 1B). In addition, we found that the expression of KRT7 was upregulated in many types of human tumors, such as bladder cancer, liver cancer and ovarian cancer (Figure 1C). Moreover, the results of immunohistochemistry provided by the HPA database showed that KRT7 was highly expressed in PAAD tissues compared with low expression in normal pancreas tissues (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

The expression level of KRT7 in PAAD and normal pancreas tissues. (A) The expression of KRT7 in PAAD (red) and normal pancreas tissue (gray) analyzed by GEPIA. (B) Meta-analyses of the KRT7 expression in PAAD samples analyzed by Oncomine. (C) The expression of KRT7 in various tumors analyzed by Oncomine. Red indicates high expression, and blue indicates low expression. (D) Immunohistochemical staining of KRT7 in PAAD tissues (a-c) and normal pancreas tissues (d-f) analyzed by the HPA database.

Correlation of KRT7 with Clinicopathological Parameters in PAAD

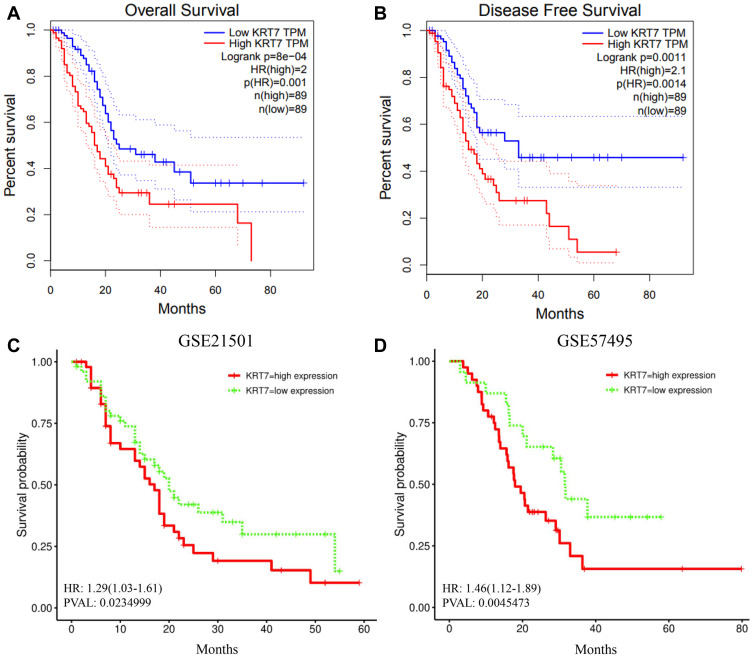

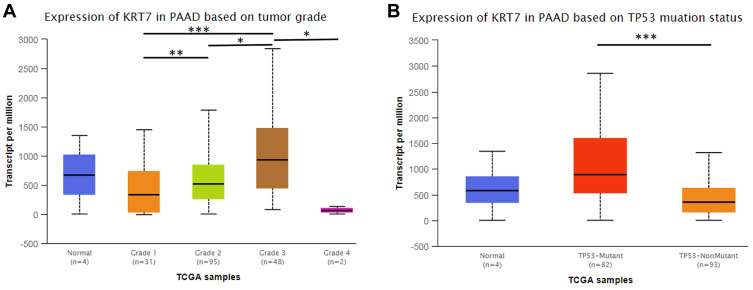

We further studied whether the expression level of KRT7 could predict the prognosis of PAAD patients via the GEPIA and PROGgeneV2 databases. Survival analysis in the GEPIA database showed that overexpressed KRT7 was correlated with poor overall survival (P = 8e-4, HR=2, Figure 2A) and disease-free survival (P = 0.0011, HR=2.1, Figure 2B) in PAAD patients. The results analyzed by the PROGgeneV2 database illustrated that patients with KRT7 overexpression had poor overall survival in GSE21501 (P = 0.0235, HR = 1.29 (1.03–1.61), Figure 2C) and GSE57495 (P = 0.0045, HR = 1.46 (1.12–1.89), Figure 2D) cohorts. The relationships between KRT7 and other clinicopathological parameters of PAAD are outlined in Table 1. We found that KRT7 expression had a significant correlation with tumor grade (Table 1, Figure 3A) and TP53 mutations (Figure 3B) according to the results from the UALCAN database. Moreover, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis proved that overexpressed KRT7 was an important and independent risk factor for poor overall survival (P = 0.006, HR =1.87 (1.2–2.915)) and disease-free survival (P = 0.019, HR =1.793 (1.097–2.933)) in PAAD patients (Tables 2 and 3). Overall, KRT7 could be considered as a reliable prognostic factor for PAAD patients.

Figure 2.

Prognostic significance of KRT7 in PAAD. (A-B) The prognostic significance of KRT7 expression in PAAD analyzed by GEPIA. (C-D) The prognostic significance of KRT7 expression in PAAD analyzed by PROGgeneV2.

Table 1.

Correlation Between KRT7 Expression and Clinicopathological Characteristics of PAAD

| Variables | No. (n=178) | KRT7 High (n=89) |

KRT7 Low (n=89) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.33 | |||

| ≥60 | 123 | 58 | 65 | |

| <60 | 55 | 31 | 24 | |

| Gender | 0.292 | |||

| Female | 80 | 36 | 44 | |

| Male | 98 | 53 | 45 | |

| Histological type | ||||

| Other subtype | 25 | 7 | 18 | 0.046 |

| Ductal type | 147 | 80 | 67 | |

| Colloid carcinoma | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Grade | 0.006 | |||

| G1 | 31 | 9 | 22 | |

| G2 | 95 | 46 | 49 | |

| G3 | 48 | 33 | 15 | |

| G4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gx | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| T classification | 0.49 | |||

| T1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| T2 | 24 | 9 | 15 | |

| T3 | 142 | 75 | 67 | |

| T4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| TX | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| N classification | 0.977 | |||

| N0 | 49 | 24 | 25 | |

| N1 | 124 | 63 | 61 | |

| NX | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| M classification | 0.543 | |||

| M0 | 80 | 39 | 41 | |

| M1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| MX | 94 | 49 | 45 | |

| Stage | 0.588 | |||

| I | 21 | 9 | 12 | |

| II | 147 | 76 | 71 | |

| III | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| IV | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Family history | 0.13 | |||

| No | 47 | 29 | 18 | |

| Yes | 64 | 29 | 35 | |

| Unknown | 67 | 31 | 36 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 1 | |||

| No | 12 | 64 | 65 | |

| Yes | 913 | 7 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 36 | 18 | 18 | |

| Diabetes history | 0.418 | |||

| No | 109 | 59 | 50 | |

| Yes | 38 | 17 | 21 | |

| Unknown | 31 | 13 | 18 | |

| Alcohol history | 0.131 | |||

| No | 64 | 26 | 38 | |

| Yes | 102 | 55 | 47 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 8 | 4 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.584 | |||

| No | 45 | 25 | 20 | |

| Yes | 90 | 44 | 46 | |

| Unknown | 43 | 20 | 23 | |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 0.679 | |||

| No | 102 | 51 | 51 | |

| Yes | 32 | 18 | 14 | |

| Unknown | 44 | 20 | 24 |

Figure 3.

The relationship between KRT7 expression and tumor grade (A) and TP53 mutations (B) in PAAD analyzed by UALCAN. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of Overall Survival in PAAD Patients

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 0.144 | 1.403 (0.891–2.207) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.35 | 0.823 (0.548–1.24) | ||

| Histological type | ||||

| Ductal type | Reference | |||

| Other subtype | 0.001 | 0.238(0.103–0.547) | 0.009 | 0.28(0.107–0.734) |

| Colloid carcinoma | 0.98 | 0.982(0.241–4.006) | 0.464 | 0.515(0.087–3.035) |

| Undifferentiated | 0.996 | – | 0.999 | – |

| Unknown | 0.996 | – | 0.999 | – |

| Grade | ||||

| G1 | Reference | |||

| G2 | 0.042 | 1.993(1.027–3.87) | 0.044 | 2.093(1.02–4.295) |

| G3+G4 | 0.008 | 2.575(1.283–5.17) | 0.017 | 2.434(1.166–5.08) |

| Gx | 0.592 | 1.754(0.225–13.66) | 0.022 | 14.67(1.483–145.09) |

| T classification | ||||

| T1+T2 | Reference | |||

| T3+T4 | 0.026 | 2.053(1.089–3.871) | 0.096 | 2.369(0.858–6.544) |

| TX | 0.997 | – | 0.997 | – |

| unknown | 0.997 | – | 0.998 | – |

| N classification | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 0.005 | 2.099(1.250–3.524) | 0.057 | 2.047(0.979–4.277) |

| NX | 0.972 | 1.027(0.234–4.501) | 0.025 | 7.338(1.279–42.11) |

| Unknown | 0.995 | – | 0.997 | – |

| M classification | ||||

| M0 | Reference | |||

| M1 | 0.905 | 0.917(0.222–3.8) | ||

| MX | 0.337 | 0.815(0.537–1.237) | ||

| Stage | ||||

| I | Reference | |||

| II | 0.032 | 2.349(1.077–5.123) | 0.208 | 0.407(0.1–1.648) |

| III+IV | 0.428 | 1.738(0.444–6.81) | 0.371 | 0.457(0.082–2.542) |

| Unknown | 0.996 | – | – | |

| Family history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.637 | 1.138 (0.665–1.95) | ||

| Unknown | 0.516 | 1.192(0.702–2.024) | ||

| Chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.663 | 1.178 (0.563–2.466) | ||

| Unknown | 0.453 | 1.209(0.736–1.985) | ||

| Diabetes history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.798 | 0.93 (0.535–1.618) | ||

| Unknown | 0.91 | 1.032(0.6–1.771) | ||

| Alcohol history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.592 | 1.128 (0.727–1.75) | ||

| Unknown | 0.94 | 1.031(0.47–2.261) | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.004 | 0.498(0.309–0.802) | 0.0001 | 0.34(0.195–0.595) |

| Unknown | 0.447 | 0.806(0.462–1.405) | 0.057 | 0.332(0.107–1.032) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.005 | 0.383(0.196–0.75) | 0.028 | 0.424(0.197–0.916) |

| Unknown | 0.913 | 1.027(0.637–1.657) | 0.554 | 1.369(0.483–3.878) |

| KRT7 | ||||

| Low | Reference | |||

| High | 0.001 | 2.095 (1.379–3.181) | 0.006 | 1.87(1.2–2.915) |

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of Disease-Free Survival in PAAD Patients

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | Reference | |||

| ≥60 | 0.851 | 1.045(0.663–1.647) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.578 | 0.883(0.57–1.369) | ||

| Histological type | ||||

| Ductal type | Reference | |||

| Other subtype | 0.007 | 0.407(0.213–0.78) | 0.377 | 0.713(0.336–1.513) |

| Colloid carcinoma | 0.997 | – | 0.998 | – |

| Undifferentiated | 0.998 | – | 0.999 | – |

| Unknown | 0.998 | – | 0.999 | – |

| Grade | ||||

| G1 | Reference | |||

| G2 | 0.03 | 2.131(1.076–4.222) | 0.202 | 1.595(0.779–3.265) |

| G3+G4 | 0.002 | 3.024(1.481–6.177) | 0.101 | 1.858(0.886–3.894) |

| Gx | 0.099 | 5.72(0.721–45.406) | 0.135 | 5.276(0.594–46.6) |

| T classification | ||||

| T1+T2 | Reference | |||

| T3+T4 | 0.021 | 2.138(1.121–4.078) | 0.962 | 1.026(0.359–2.926) |

| TX | 0.997 | – | 1 | – |

| Unknown | 0.997 | – | 0.998 | – |

| N classification | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 0.026 | 1.753(1.068–2.878) | 0.284 | 1.421(0.747–2.704) |

| NX | 0.995 | – | 0.998 | – |

| Unknown | 0.997 | – | 0.998 | – |

| M classification | ||||

| M0 | Reference | |||

| M1 | 0.861 | 0.881(0.213–3.638) | 0.998 | 0.997(0.08–12.48) |

| MX | 0.005 | 0.521(0.329–0.825) | 0.061 | 0.632(0.391–1.022) |

| Stage | ||||

| I | Reference | |||

| II | 0.014 | 2.688(1.217–5.937) | 0.845 | 1.15(0.286–4.627) |

| III+IV | 0.172 | 2.599(0.659–10.24) | 0.872 | 1.217(0.111–13.31) |

| Unknown | 0.995 | – | – | – |

| Family history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.818 | 1.065(0.62–1.831) | ||

| Unknown | 0.84 | 1.059(0.605–1.855) | ||

| Chronic pancreatitis | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.623 | 0.776(0.282–2.137) | ||

| Unknown | 0.371 | 0.737(0.378–1.438) | ||

| Diabetes history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.817 | 0.933(0.52–1.674) | ||

| Unknown | 0.126 | 0.561(0.268–1.176) | ||

| Alcohol history | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.307 | 1.284(0.795–2.073) | ||

| Unknown | 0.525 | 0.732(0.279–1.919) | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.997 | 1.001(0.583–1.719) | ||

| Unknown | 0.797 | 1.1(0.532–2.276) | ||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.551 | 0.849(0.495–1.455) | ||

| Unknown | 0.807 | 0.927(0.502–1.711) | ||

| KRT7 | ||||

| Low | Reference | |||

| High | 0.000 | 2.313(1.476–3.626) | 0.019 | 1.793(1.097–2.933) |

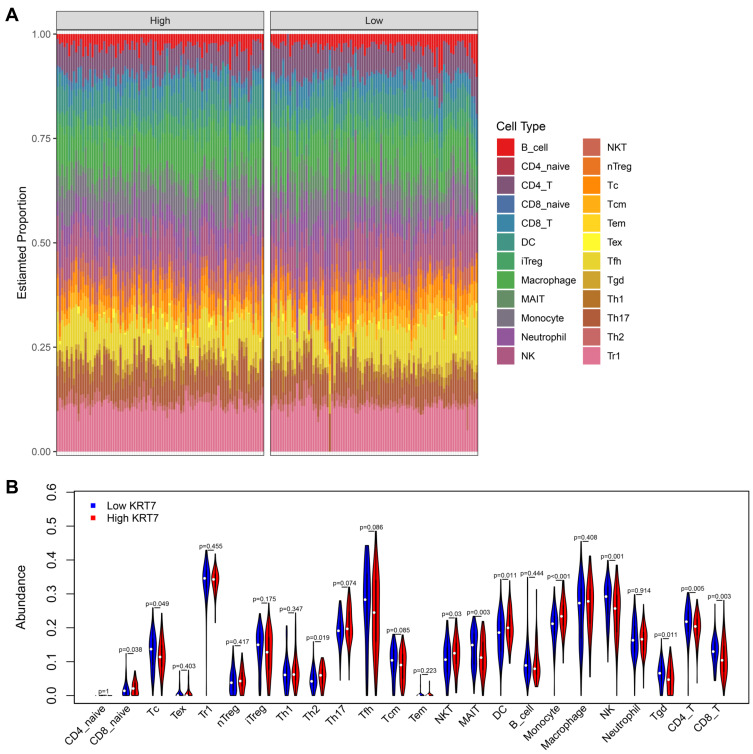

Relationship Between KRT7 and Immune Molecules in PAAD

Due to the critical role of immune response in tumor development and treatment, we further explored the relationship between KRT7 and immune infiltration in PAAD. The ImmuCellAI database helped us precisely determine the infiltration level of 24 immune cell types in PAAD samples (Figure 4A). Obviously, the proportions of immune cells varied significantly between different PAAD samples. In terms of quantitative abundance, the proportions of Tc, MAIT, NK, Tgd, CD4+T and CD8+T cells were lower in the high KRT7 expression group than in low KRT7 expression group. By contrast, the proportions of CD8+ naïve T cells, Th2 cells, NKT cells, DCs and monocytes were relatively higher in the low KRT7 expression group than in the high KRT7 expression group (all P < 0.05, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the difference in immune infiltration between the high and low KRT7 expression groups analyzed by ImmuCellAI. (A) The landscape of immune infiltration levels in TCGA-PAAD samples. (B) The difference of 24 immune infiltrating cells in the high and low KRT7 expression groups in PAAD.

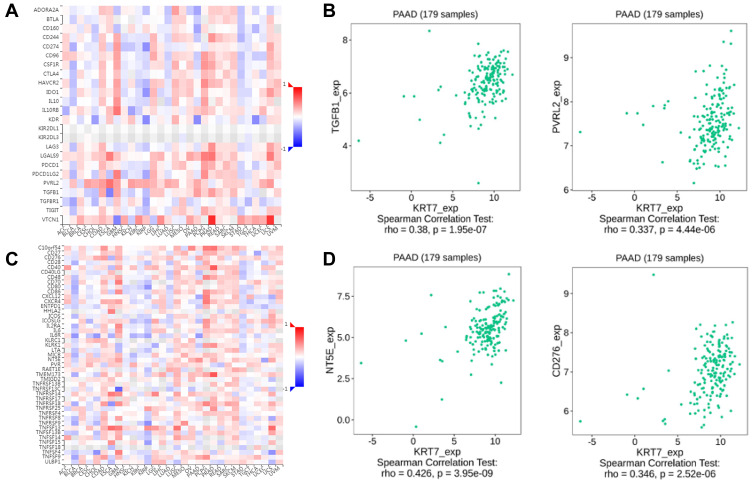

Concomitantly, the TISIDB database was used to assess the relationships between KRT7 and immunomodulators. The correlations between KRT7 and immunoinhibitors and immunostimulators are shown in Figure 5A and C, respectively. The immune molecules showing the greatest correlation with KRT7 were TGFB1 (P = 1.95e−7, r = 0.38) and PVRL2 (P = 4.46e−6, r = 0.337) (Figure 5B) among the immunosuppressants, and NT5E (P = 3.95e−9, r = 0.426) and CD276 (P = 2.52e−6, r = 0.346) (Figure 5D) among the immunostimulants. These results strongly confirm that KRT7 have a significant effect in the regulation of the above immune molecules in PAAD.

Figure 5.

The correlation between KRT7 expression with immunomodulators. (A-B) The correlation between KRT7 expression with immunoinhibitors and the top 2 immunoinhibitors showing the greatest correlation with KRT7 in PAAD. (C-D) The correlation between KRT7 expression with immunostimulators and the top 2 immunostimulators showing the greatest correlation with KRT7 in PAAD.

Analysis of Coexpressed Genes Correlated with KRT7 in PAAD

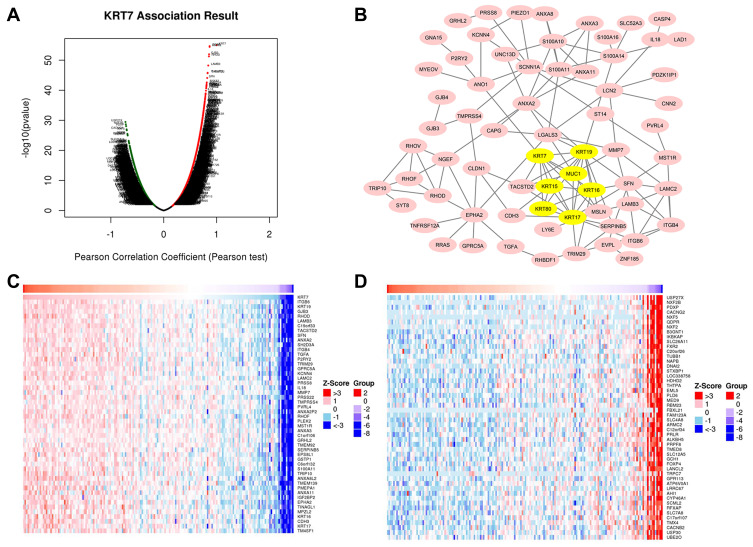

As shown in Figure 6A, almost all genes expressed in PAAD were related to KRT7 expression. Specifically, 5400 genes marked in red were positively correlated with KRT7 in PAAD, while 5265 genes marked in green were negatively correlated with KRT7 (FDR < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Genes correlated with KRT7 in PAAD analyzed by LinkedOmics. (A) All expressed genes correlated with KRT7 in PAAD. (B) Protein–protein interaction network and MCODE analysis of coexpressed genes. (C) Top 50 genes positively related to KRT7 in PAAD. (D) Top 50 genes negatively related to KRT7 in PAAD.

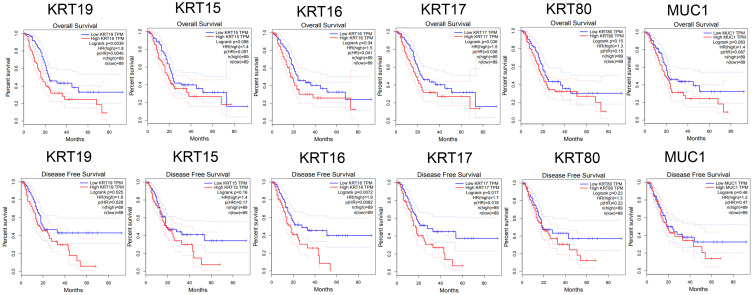

A total of 120 coexpressed genes that had a strong positive correlation with KRT7 were used to construct a protein–protein interaction network, and the most important module in the network was highlighted in yellow (Figure 6B). The top 50 significant genes that were positively (Figure 6C) and negatively (Figure 6D) correlated with KRT7 are shown in the heat map. The top 7 highly connected genes included KRT7, KRT19, KRT15, KRT16, KRT17, KRT80 and MUC1 in the module were considered as the hub genes in PAAD. The survival correlation of 6 hub genes (KRT19, KRT15, KRT16, KRT17, KRT80 and MUC1) in the module was analyzed using GEPIA, and the results showed that KRT19, KRT16 and KRT17 were associated with the overall and disease-free survival rates in PAAD patients (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Survival analysis of 6 hub genes in PAAD performed by GEPIA. The results showed that KRT19, KRT16 and KRT17 were associated with the overall and disease-free survival rates in PAAD patients (P < 0.05).

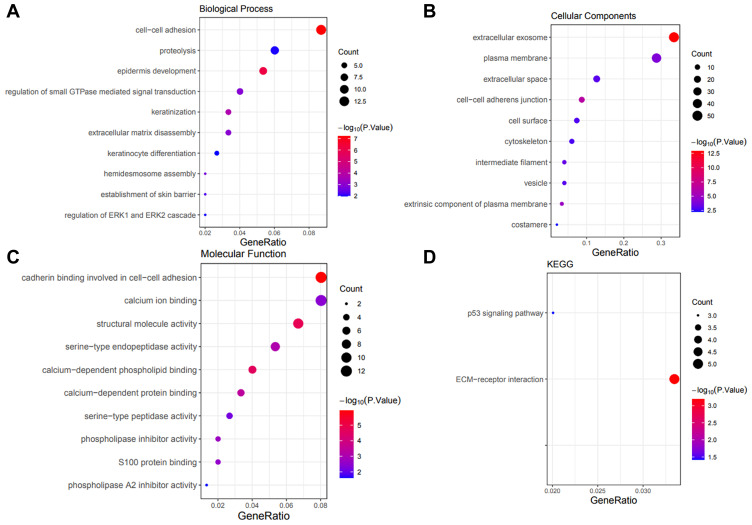

GO and KEGG Analysis of Coexpressed Genes

We input 120 coexpressed genes into the DAVID database to perform functional enrichment analysis. GO analysis showed that these genes correlated with KRT7 were mainly associated with the biological processes of cell–cell adhesion, proteolysis, epidermis development, etc. (Figure 8A). They were mainly located in the extracellular exosome, plasma membrane, extracellular space, etc. (Figure 8B), acting as cadherin binding involved in cell–cell adhesion, calcium ion binding, structural molecule activity, etc. (Figure 8C). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that the p53 signaling pathway and ECM–receptor interaction were the most significantly enriched pathways (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Significant GO and KEGG terms of the coexpressed genes. (A) Biological process analysis of the coexpressed genes. (B) Cell component analysis of the coexpressed genes. (C) Molecular function analysis of the coexpressed genes. (D) KEGG pathway analysis of the coexpressed genes.

Interacting Genes and GSEA of KRT7

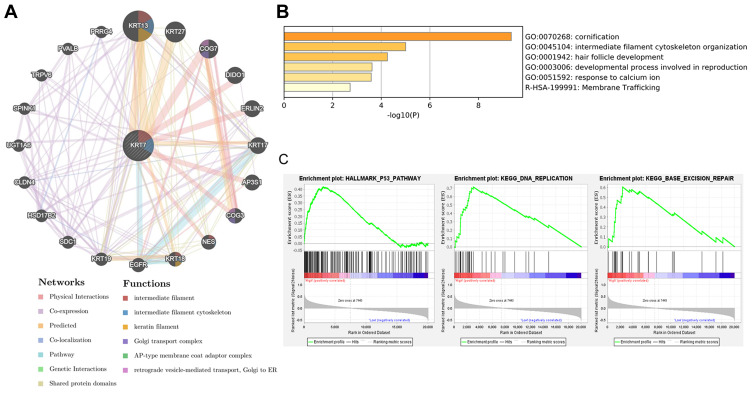

To get a better understanding of biological functions of KRT7, the protein–protein interaction network of KRT7 and its interacting genes was conducted via the GeneMANIA database and displayed in Figure 9A. The results of Metascape analysis showed that KRT7 was involved in cornification, intermediate filament cytoskeleton organization, hair follicle development, developmental process involved in reproduction, response to calcium ion and membrane trafficking (Figure 9B). Moreover, GSEA results indicated that the significant pathways of high KRT7 expression (FDR q-value <0.25, NOM p-value <0.05) in the MSigDB collection (c2.cp.kegg and h.all.v.7.1.symbols.gmt) were the p53 pathway, DNA replication and base excision repair (Figure 9C). These findings suggest that KRT7 play an important role in the development and progression of PAAD.

Figure 9.

The biological functions of KRT7 and its related genes. (A) Protein–protein interaction network of KRT7 and its related genes analyzed by GeneMANIA. (B) Functional enrichment pathways of KRT7 and its related genes analyzed by Metascape. (C) Significant pathways in the data sets of high KRT7 expression analyzed by GSEA.

Discussion

As we all known, PAAD is the most common malignant tumor with high recurrence and poor prognosis.1 Promising biomarkers of PAAD need to be identified for improvement of the diagnosis and therapy to reduce mortality. KRT7 is a member of the keratin gene family, which mainly plays a role in maintaining the structural integrity of epithelial cells. Many studies have reported that dysregulation of keratin expression is correlated with worse patient prognosis in many tumor types. For example, downregulated KRT7 was significantly associated with the progress and poor prognosis in patients with cervical cancer.29 A low level of KRT18 was associated with TNM stage, lymph node metastasis, and unfavorable survival in breast cancer patients.30 Altered levels of KRT19 were associated with prognosis and metastasis in patients with various cancer types.31 However, the role of KRT7 in PAAD and its functional mechanisms are still unclear. In this study, we compared the differences of KRT7 expression between PAAD tissues and normal pancreas tissues. The clinical significance and potential mechanism of KRT7 in PAAD, as well as its correlation with immunity were analyzed by bioinformatics analysis.

Our research group comprehensively analyzed the roles of KRT7 expression in PAAD by utilizing online databases. Firstly, the GEPIA and Oncomine databases showed that the mRNA expression of KRT7 was increased in PAAD tissues compared with normal tissues, which was consistent with the previous study.11 Immunohistochemical images from HPA database also verified high staining of KRT7 in PAAD tissues. More importantly, consistent with previous findings in other cancers, Kaplan–Meier survival curves produced by GEPIA and PROGgeneV2 indicated that high expression of KRT7 was associated with poor prognosis in PAAD patients.8–10 Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis proved that overexpressed KRT7 was an important and independent risk factor for overall survival and disease-free survival in PAAD. In addition, we found that high expression of KRT16, KRT17 and KRT19 was associated with poor overall survival and disease-free survival in PAAD. It has been reported that many members of the keratin family was involved in the prognosis and metastasis of human cancers,30–32 which further confirmed the reliability of our results. All these findings demonstrated the possible prognostic value of KRT7 expression in PAAD.

Our results showed that KRT7 not only participated in the progression and prognosis of PAAD, but also played a pivotal role in the immune microenvironment of PAAD. One major finding of this study was that KRT7 expression in PAAD was associated with infiltration levels of immune cells. Through ImmuCellAI analysis, we found that the expression of KRT7 was significantly correlated with the number of DCs, monocytes, NK and a variety of T cells, namely, CD8+ naïve T cells, Tc, Th2 cells, NKT cells, MAIT, Tgd, CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells. These immune cells play an important role in the tumor occurrence, progression and response to therapy in PAAD. For instance, a paucity of DCs leads to dysfunctional immune surveillance in pancreatic cancer.33 Dense fibrosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma can be induced by manipulating tumor-infiltrating monocytes, leading to enhanced chemotherapy efficacy.34 In pancreatic cancer, NK cell activity decreased as cancer progressed, and decreased NK cell activity was associated with poor clinical outcomes in terms of response to chemotherapy, tumor progression and survival.35 The current study showed that a variety of T cells play the role of anti-tumor immune effector cells in PAAD. Lymph node desmoplasia of pancreatic adenocarcinoma was associated with activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts and Th2 infiltration.36 NKT cells regulated pancreatic cancer by modulating tumour-associated macrophages through their production of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 and 5-lipoxygenase, and the absence of NKT cells led to aggressive development of pancreatic cancer.37 Tgd cells support the oncogenesis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by inhibiting αβ T cells.38 High levels of infiltrating CD4+ and CD8 T+ cells showed a good prognostic impact in pancreatic cancer.39 Salas et al have reported that cytokeratin family also played a critical role in regulating innate immunity.40 The interaction between tumor cells with various cells, including stromal cells, vascular cells, and immune cells, raises the possibility of tumor immune escape, resulting in a fatal prognosis for patients.41 Therefore, we speculate that KRT7-mediated changes in the infiltration level of immune cells, especially T lymphocyte, which is closely related to immune function, thereby affecting the tumor microenvironment by the immune suppression mechanism. Dysregulation of the tumor immune microenvironment affected by KRT7 overexpression might be responsible for the poor prognosis of PAAD, which has implications for checkpoint immunotherapy. However, the interaction between KRT7 and immune checkpoints has rarely been reported.

In recent years, immunotherapy, especially immune checkpoint blockade, has been proven as an effective treatment option to stop cancer progression and metastasis. In this study, we found that the expression of KRT7 also had a positive correlation with four common immune checkpoint expression, namely, TGFB1, PVRL2, NT5E and CD276 by using the TISIDB database. The combined blockade of TGFB1 and GM-CSF could improve the chemotherapy effect of pancreatic cancer by inhibiting M2 polarized TAMs and inducing CD8+ T cells.42 Targeting PVRIG-PVRL2 interactions could enhance CD8+ T cell function and inhibit tumor growth.43 The immune checkpoints PVR and PVRL2 are prognostic indicators of acute myeloid leukemia, and their blockade could be a new treatment option.44 The ectonucleotides CD39 and CD73/NT5E are newly recognized novel checkpoint inhibitor targets.45 Du et al found that chimeric antigen receptor T cells targeting B7-H3/CD276 could inhibit the growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in vitro and in orthotopic and metastatic xenograft mouse models.46 It has been confirmed that immune checkpoints regulate the anti-tumor immunity of the body, and KRT7 might affect the anti-tumor immune response by increasing the expression of immune checkpoints and promoting immune cell infiltration. Therefore, KRT7 combined with immune checkpoint blockade might has the potential to promote immune cell infiltration and enhance the survival of patients with PAAD by stimulating immune responses. This study has demonstrated the clinical significance of KRT7, but in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to further demonstrate the mechanisms of KRT7 in the immune regulation of PAAD.

Through the functional enrichment analysis, we found that the genes coexpressed with KRT7 obtained from the LinkedOmics database were mainly associated with critical biological processes, such as cell–cell adhesion, proteolysis, and epidermis development, as well as the regulation of the p53 signaling pathway and ECM-receptor interaction, thereby affecting the tumorigenesis and progression of PAAD. The results of GSEA analysis indicated that KRT7 was associated with the p53 pathway in PAAD. The results of UALCAN analysis showed that the expression of KRT7 was significantly correlated with tumor grade and TP53 mutations. TP53 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and mutations of TP53 can cause abnormal cell proliferation and promote tumor progression. Some clinical evidence suggested that TP53 could be used as a biomarker for prognosis and therapy prediction.47 KRT19 together with p53 mutations promotes advanced disease and unfavorable prognosis in hepatocellular carcinomas.48 TP53 acts as a co-repressor to regulate KRT14 expression during epidermal cell differentiation.49 Consequently, we speculated that KRT7 might promote the occurrence and development of PAAD through the p53 pathway and become an indicator of TP53 mutations.

Given the limited sample data of PAAD patients available to us, we analyzed data from a large number of public databases to investigate the clinical values of KRT7 expression in PAAD. However, our study had some limitations. This study is a retrospective study based on bioinformatics analysis. Therefore, more solid experiments and well-designed prospective studies are warranted to provide strong evidence to verify our findings on the functional roles and potential mechanism of KRT7 in PAAD due to the complexity of cancer genomics.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that both the transcriptional and translational levels of KRT7 were significantly elevated in PAAD patients. High expression of KRT7 predicted a worse prognosis in PAAD and Cox regression results showed that KRT7 was an independent prognostic indicator in PAAD. In addition, we also found that the expression of KRT7 was positively associated with the infiltration of DCs, monocytes, NK and a variety of T cells and four common immune checkpoints expression. These findings provide evidence for the use of KRT7 as an effective biomarker for prognostic monitoring in PAAD and as a therapeutic target modulating the tumor immune microenvironment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Nanning Qingxiu District Science and Technology Project (No. 2019026) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81960126).

Abbreviations

PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; KRT7, Keratin 7; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; HPA, Human Protein Atlas; ImmuCellAI, Immune Cell Abundance Identifier; DAVID, Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, genotype-tissue expression; HR, Hazard Ratio; CIBERSORT, Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts; TIMER, Tumor Immune Estimation Resource; DCs, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer cells; Tc, cytotoxic T cells; Tex, exhausted T cells; Tr1, type 1 regulatory T cells; nTreg, natural regulatory T cells; iTreg, induced regulatory T cells; Th1, Th2, and Th17, T helper 1, 2, and 17 cells; Tfh, follicular T helper cells; Tcm, central memory T cells; Tem, effector memory T cells; NKT, natural killer T cells; MAIT, mucosal-associated invariant T cells; Tgd, gamma delta T cells; STRING, Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes; MCODE, Molecular Complex Detection.

Data Sharing Statement

The authors certify that all the original data in this research could be obtained from public database. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest for this work or regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Parekh HD, Starr J, George TJ Jr. The multidisciplinary approach to localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(12):73. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0515-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(43):4846–4861. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i43.4846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moletta L, Serafini S, Valmasoni M, Pierobon ES, Ponzoni A, Sperti C. Surgery for recurrent pancreatic cancer: is it effective? Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:7. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilic M, Ilic I. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(44):9694–9705. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i44.9694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn DH, Ramanathan RK, Bekaii-Saab T. Emerging therapies and future directions in targeting the tumor stroma and immune system in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10:6. doi: 10.3390/cancers10060193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob JT, Coulombe PA, Kwan R, Omary MB, Types I, Keratin Intermediate II. Filaments. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan X, Hobbs RP, Coulombe PA. The expanding significance of keratin intermediate filaments in normal and diseased epithelia. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kryvenko ON, Jorda M, Argani P, Epstein JI. Diagnostic approach to eosinophilic renal neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(11):1531–1541. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0653-RA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo H-T, Liang C-X, Luo R-C, Gu W-G. Identification of relevant prognostic values of cytokeratin 20 and cytokeratin 7 expressions in lung cancer. Biosci Rep. 2017;37:6. doi: 10.1042/BSR20171086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L-Z, Yang L-X, Zheng B-H, et al. CK7/CK19 index: a potential prognostic factor for postoperative intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117(7):1531–1539. doi: 10.1002/jso.25027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schüssler MH, Skoudy A, Ramaekers F, Real FX. Intermediate filaments as differentiation markers of normal pancreas and pancreas cancer. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(3):559–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2015;19(1A):A68–A77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9(2):166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontén F, Schwenk JM, Asplund A, Edqvist PHD. The Human Protein Atlas as a proteomic resource for biomarker discovery. J Intern Med. 2011;270(5):428–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goswami CP, Nakshatri H. PROGgeneV2: enhancements on the existing database. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:970. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, et al. UALCAN: a portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao Y-R, Zhang Q, Lei Q, et al. ImmuCellAI: a unique method for comprehensive T-cell subsets abundance prediction and its application in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(7):1902880. doi: 10.1002/advs.201902880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aran D, Hu Z, Butte AJ. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1349-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ru B, Wong CN, Tong Y, et al. TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(20):4200–4202. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasaikar SV, Straub P, Wang J, Zhang B. LinkedOmics: analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D956–D963. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Mering C, Huynen M, Jaeggi D, Schmidt S, Bork P, Snel B. STRING: a database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):258–261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, et al. DAVID Bioinformatics Resources: expanded annotation database and novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(WebServer issue):W169–W175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franz M, Rodriguez H, Lopes C, et al. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W60–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEA-P: a desktop application for gene set enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(23):3251–3253. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashiguchi M, Masuda M, Kai K, et al. Decreased cytokeratin 7 expression correlates with the progression of cervical squamous cell carcinoma and poor patient outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45(11):2228–2236. doi: 10.1111/jog.14108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi R, Wang C, Fu N, et al. Downregulation of cytokeratin 18 enhances BCRP-mediated multidrug resistance through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and predicts poor prognosis in breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(5):3015–3026. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehrpouya M, Pourhashem Z, Yardehnavi N, Oladnabi M. Evaluation of cytokeratin 19 as a prognostic tumoral and metastatic marker with focus on improved detection methods. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(12):21425–21435. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma P, Alsharif S, Fallatah A, Chung BM. Intermediate filaments as effectors of cancer development and metastasis: a focus on keratins, vimentin, and nestin. Cells. 2019;8:5. doi: 10.3390/cells8050497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegde S, Krisnawan VE, Herzog BH, et al. Dendritic cell paucity leads to dysfunctional immune surveillance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(3):289–307.e289. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long KB, Gladney WL, Tooker GM, Graham K, Fraietta JA, Beatty GL. IFNγ and CCL2 cooperate to redirect tumor-infiltrating monocytes to degrade fibrosis and enhance chemotherapy efficacy in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(4):400–413. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HS, Leem G, Kang H, et al. Peripheral natural killer cell activity is associated with poor clinical outcomes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nizri E, Bar-David S, Aizic A, et al. Desmoplasia in lymph node metastasis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma reveals activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts pattern and T-helper 2 immune cell infiltration. Pancreas. 2019;48(3):367–373. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janakiram NB, Mohammed A, Bryant T, et al. Loss of natural killer T cells promotes pancreatic cancer in LSL-Kras(G12D/+) mice. Immunology. 2017;152(1):36–51. doi: 10.1111/imm.12746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daley D, Zambirinis CP, Seifert L, et al. γδ T cells support pancreatic oncogenesis by restraining αβ T cell activation. Cell. 2016;166:6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Zhao J, Zhao H, et al. Infiltrating CD4/CD8 high T cells shows good prognostic impact in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10(8):8820–8828. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salas PJ, Forteza R, Mashukova A. Multiple roles for keratin intermediate filaments in the regulation of epithelial barrier function and apico-basal polarity. Tissue Barriers. 2016;4(3):e1178368. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1178368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kudo-Saito C, Ozaki Y, Imazeki H, et al. Targeting Oncoimmune Drivers of Cancer Metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Q, Wu H, Li Y, et al. Combined blockade of TGf-β1 and GM-CSF improves chemotherapeutic effects for pancreatic cancer by modulating tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(8):1477–1492. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02542-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murter B, Pan X, Ophir E, et al. Mouse PVRIG has CD8 T cell-specific coinhibitory functions and dampens antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(2):244–256. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamm H, Klingler F, Grossjohann E-M, et al. Immune checkpoints PVR and PVRL2 are prognostic markers in AML and their blockade represents a new therapeutic option. Oncogene. 2018;37(39):5269–5280. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0288-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allard B, Longhi MS, Robson SC, Stagg J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev. 2017;276(1):121–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du H, Hirabayashi K, Ahn S, et al. Antitumor responses in the absence of toxicity in solid tumors by targeting B7-H3 via chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cicenas J, Kvederaviciute K, Meskinyte I, Meskinyte-Kausiliene E, Skeberdyte A, Cicenas J. KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, SMAD4, BRCA1, and BRCA2 mutations in pancreatic cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2017;9:5. doi: 10.3390/cancers9050042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan R-H, Jeng Y-M, Hu R-H, et al. Role of p53 and β-catenin mutations in conjunction with CK19 expression on early tumor recurrence and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(2):321–329. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1373-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cai B-H, Hsu P-C, Hsin IL, et al. p53 acts as a co-repressor to regulate keratin 14 expression during epidermal cell differentiation. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]