Abstract

COVID-19 is a new disease that presents mainly with respiratory symptoms. However, it can present with a multitude of signs and symptoms that affect various body systems and several oral manifestations have also been reported. We carried out a systematic review to explore the types of oral mucosal lesions that have been reported in the COVID-19-related literature up to 25 March 2021. A structured electronic database search using Medline, Embase, and CINAHL, as well as a grey literature search using Google Scholar, revealed a total of 322 studies. After the removal of duplicates and completion of the primary and secondary filtering processes, 12 studies were included for final appraisal. In patients with COVID-19 infection, we identified several different types of oral mucosal lesions at various locations within the oral cavity. Most of the studies appraised had a high risk of bias according to the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist. The current published literature does not allow differentiation as to whether the oral lesions were caused by the viral infection itself, or were related to oral manifestations secondary to existing comorbidities or the treatment instigated to combat the disease. It is important for healthcare professionals to be aware of the possible link between COVID-19 and oral mucosal lesions, and we hereby discuss our findings.

Keywords: COVID-19, oral manifestation, oral lesions, oral mucosa

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic commenced in December 2019 and has so far affected 163 million people, with over three million deaths worldwide.1 The pandemic appears to be far from over, with various reports of emerging new variants (despite ongoing efforts with the worldwide vaccination rollout) suggesting that there is a continued need for medical practitioners to remain up to date with their knowledge of its signs and symptoms. It has been suggested that angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, which are highly expressed in oral tissues such as the tongue, epithelial linings of the salivary ducts, salivary glands, and taste buds, may act as entry points for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.2 The oral mucosa may therefore act as a portal of entry for the virus, leading to colonisation and resulting in oral signs and symptoms. Acute loss or altered sense of taste and smell have been noted to be among the most common symptoms with a prevalence of 45%, and they have been formally recognised by the United Kingdom National Health Service as being some of the main symptoms for suspicion of COVID-19 infection.3, 4

A number of oral mucosal lesions have been reported in COVID-19 patients. These include erythematous plaque, ulcers, blisters, bullae, petechiae, mucositis, and desquamative gingivitis.3 The most commonly involved oral sites have been reported to be tongue, palate, lips, gingiva, and buccal mucosa.3, 5 It is unclear as to whether the oral lesions described are manifestations of COVID-19 or the results of immunosuppression and the side effects of treatment. It is well established that various types of oral lesions are manifestations of several other virus illnesses,6 so it is plausible that lesions can also be caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

A knowledge of oral lesions is important for all healthcare professionals, but particularly for general dental and medical practitioners, as well as specialists in oral medicine and oral and maxillofacial surgery. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and consolidate the types of oral mucosal lesions in patients with COVID-19 disease, and to report on the location of these lesions within the oral mucosa.

Methods

Protocol registration

A protocol for the systematic review was developed and registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database under registration CRD42021245738.7

Study eligibility and selection

Observational studies that investigated the prevalence of oral lesions were included, and the PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) strategy was utilised. Case reports, review articles, and conference abstracts were excluded, but case series were included so that more studies would be captured. Only studies published in the English language were included.

Search strategy

A structured electronic search was carried out using the electronic databases Medline, Embase and CINAHL. Grey literature was searched using Google Scholar. Reference lists of the included articles were also checked to identify other potential studies. The search included all articles published until 25 March 2021 across all the mentioned databases. Search terms using keywords and the medical subject headings utilised in this review have been detailed in the published protocol.7

Study selection and data collection

Primary screening was carried out by two authors (NB and KZ) who independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the articles identified from the electronic databases. For the studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, a secondary filtering was carried out in which the full text articles were reviewed independently by the above-mentioned authors.

A standardised data extraction proforma was employed for all the included studies to allow meaningful comparison. Any disagreement and discrepancy between the two authors (NB and KZ) was either resolved by discussion or after discussion with the third author (RPS). Two authors (NB and KZ) collected the required information using the standardised proforma, and the third author (RPS) checked and confirmed the data collected. The data collection proforma included patients’ demographics, the type of oral lesion, and the site affected.

Data synthesis and risk of bias

Narrative synthesis of the included studies was carried out. Meta-analysis was not planned, as we did not expect homogeneity of the studies. For the risk of bias, two reviewers (NB and KZ) independently assessed the studies as per the Joanna Briggs Institute tool.8 The studies were classified as having a high, medium, or low risk of bias when they reached 49% ‘yes’, 50%-69% ‘yes’, and more than 70% ‘yes’, respectively.

Results

Study selection

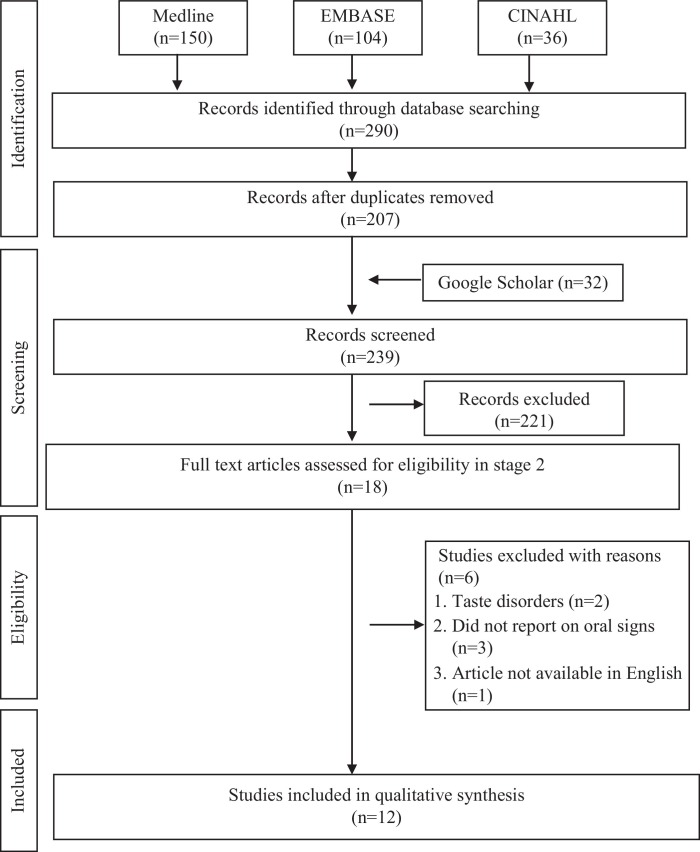

In total, 290 studies were initially identified from the electronic databases, with a further 32 from the grey literature, to the date of 25 March 2021. The outcomes of the primary and secondary screening, removal of duplicates, and final inclusions are shown in Fig. 1. The final count included 12 studies that were deemed suitable for appraisal in this systematic review. Their characteristics, including the demographic details and oral lesions reported, are presented in Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and selection criteria adapted from PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of included studies (n = 12).

| First author, year, and reference | Country | Design | Date data collected | Sample | Age (years) | Location of oral lesion | Type of oral lesions | Risk of biasa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | ||||||||

| Abubakr 20219 | Egypt | CSS | NS | 665 | 36.19 (9.11) | 19 - 50 | NS | Ulcerations (n = 117, 20.4%), xerostomia (n = 273, 47.6%), oral or dental pain (n = 132, 23%), pain in jaw joint (n = 69, 12%), halitosis (n = 60, 10.5%), and combined manifestations (n = 162, 28.3%) | High |

| M:165, F:408 | |||||||||

| Bardellini 202114 | Italy | CSS | March - April 2020 | 27 | 4.2 (1.7) | 3 months - 14 years | Tongue (n = 3, 11.1%) | Oral pseudomembranous candidiasis (n = 2, 7.4 %), geographic tongue (n = 1, 3.7%), coated tongue (n = 2, 7.4%) | Moderate |

| M:19, F:8 | |||||||||

| Brandão 202118 | Brazil | CS | NS | 8 | 54 | (28 to 83) | Tongue (n = 6), lip (n = 3), palate (n = 1), labial mucosa (n = 1) and peritonsillar (n = 1) | Ulcer (n = 4, 50%), focal erythema/ petechiae (n = 1, 13%), aphthous-like ulcers (n = 2, 25%), haemorrhagic ulcer (n = 2, 25%) | High |

| M:5, F:3 | |||||||||

| Cruz Tapia 202019 | Columbia, Brazil and Mexico | CS | NS | 4 | 47.2 (6.8) | 41 - 55 | Palate (n = 3), tongue (n = 1), non-specific mucositis (n = 1) | Angina bullosa haemorrhagic-like lesion (n = 2, 50%), vascular disorder associated with COVID-19 (n = 1, 25%), mucosal non-specific localised vasculitis and thrombosis (n = 1, 25%) | High |

| M:1, F:3 | |||||||||

| Falah 202010 | Pakistan | CSS | April - June 2020 | 10 | 6 | 4 months - 11 years | Oral cavity (unspecified) | Oral cavity changes (n = 9, 90%) (unspecified) | High |

| M:8, F:2 | |||||||||

| Favia 202115 | Italy | CSS | October - December 2020 | 123 | Median 72 | - | Tongue, palate, lip, cheek and papillae (unspecified) | Geographic tongue (n = 2, 2%), fissured tongue (n = 3, 2%), ulcerative lesion (n = 65, 53%), blisters (n = 19, 15%), hyperplasia of papillae (n = 48, 39%), angina bullosa (n = 11, 9%), candidiasis (n = 28, 23%), necrotising ulcerative gingivitis (n = 7, 6%), petechiae (n = 14, 11%) and spontaneous oral haemorrhage (n = 1, 1%) | High |

| M:70, F:53 | |||||||||

| Fidan 202112 | Turkey | CSS | April - October 2020 | 74 | 45.6 (12.8) | 19 - 78 | Tongue (n = 23), buccal mucosa (n = 20), gingiva (n = 11) and palate (n = 4) | Oral lesions (n = 58, 78%) of which aphthous-like ulcers (n = 27, 46.6%), erythema (n = 19, 32.8%) and lichen planus (n = 12, 20.6%) | High |

| M:49, F:25 | |||||||||

| Halepas 202113 | USA | CSS | March - June 2020 | 47 | 9 (5) | 1.3 - 20 | Lips, tongue and other (unspecified) | Red or swollen lips (n = 23, 48.9%), strawberry tongue = (n = 5, 10.6%) and other oral manifestation (n = 7, 14.9%) (unspecified) | High |

| M:24, F:23 | |||||||||

| Katz 202111 | USA | CSS | NS | 6 | In age group 10-34 years | - | NS | Prevalence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in COVID-19 group (n = 889) was 0.67% (n = 6) compared with 0.148% (n = 1468) in the total hospital population (n = 987,849) | High |

| M:6, F:0 | |||||||||

| Martín Carreras-Presas 202117 | Spain | CS | March - April 2020 | 3 | 60 | 56 - 65 | Palate (n = 2), inner lip mucosa (n = 1) and gingiva (n = 1) | Herpetic recurrent stomatitis (n = 1, multiple ulcerations on palate (n = 1), lip blisters and desquamative gingivitis (n = 1) | High |

| M:2, F:1 | |||||||||

| Mascitti 202016 | France | CSS | March 2020 | 40 | Median (IQR) 57.6 (49.4 - 69.1) | Inner cheeks (n = 13) and tongue (n = 1) | Oral lichenoid lesions (32.5%, n = 13), oral enanthema (27.5%, n = 11), macroglossia (25%, n = 10), herpes (2.5%, n = 1) and cheilitis (12.5%, n = 5) | Low | |

| M:31, F:9 | |||||||||

| Sinadinos 202020 | UK | CS | NS | 3 | 60 | 56 - 65 | Palate (n = 2), labial mucosa (n = 1) and gingiva (n = 1) | Herpetic recurrent stomatitis (n = 2, 67%), erythema multiforme (n = 33%) | High |

| M:2, F:1 |

CS, case series; CSS, cross-sectional study; M, Male; F, Female.

NS not specified.

Assessed by the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for case reports and prevalence studies.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias assessment (as per the Joanna Briggs critical appraisal tool) of each of the included studies is indicated in Table 1. Most had a high risk of bias.

Narrative synthesis

Descriptions of oral mucosal lesions were reported in all the studies, but there was no consistency in the mode of reporting. One study reported oral lesions along with oral/dental pain, pain in jaw joints, and halitosis.9 Reporting the signs and symptoms together made it difficult to establish the specific features of the lesions. It was also unclear whether the pain and other symptoms were a result of the stated oral lesions. Some studies reported changes in the oral cavity, but the type of lesion was unspecified.10, 11

The lesions were of several types in various locations (Table 1, Table 2 ). The most commonly reported lesion was oral ulceration, which was reported in up to 47% (n = 27) of the cases in one study.12 Other common oral mucosal changes included changes in the tongue including strawberry tongue, geographic tongue, fissured tongue, and macroglossia, which has even led to a terminology of ‘covid tongue’,13, 14, 15, 16 with one study reporting these changes in up to 25% of cases (n = 10).16 Gingival manifestations included necrotic gingivitis and desquamative gingivitis.15, 17 In two studies, haemorrhagic lesions/ulcers were also reported in up to 50% of cases, but the sample sizes were very small.18, 19 Herpetic stomatitis was noted in two case series.17, 20 The most common location of the lesions was the tongue followed by the palate and buccal/ labial mucosa and gingiva. One study reported only recurrent aphthous stomatitis in COVID-19 patients, and another reported oral changes but failed to describe what they were.10, 11 Table 2 is a summary of the oral lesions identified.

Table 2.

Summary of types of oral mucosal lesions in COVID-19 patients.

| Ulcerative lesions (aphthous-like ulceration, herpetic stomatitis, non-specific ulcers, and erythema multiforme) |

| Tongue changes (geographic tongue, red or swollen tongue, strawberry tongue, fissured tongue, macroglossia, and coated tongue) |

| Haemorrhagic lesions (angina bullosa, mucosal vasculitis, thrombosis, petechiae, haemorrhagic ulcer, focal erythema, and spontaneous oral haemorrhage) |

| Gingival lesions (desquamative gingivitis, necrotising ulcerative gingivitis, and papillary hyperplasia) |

| Candidal lesions (oral pseudomembranous candidiasis and unspecified candidiasis) |

| Oral lichenoid lesions |

| Oral enanthema |

| Non-specific blisters |

| Mucositis |

All studies relied on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT- PCR) tests after nasal and pharyngeal swabs for diagnosis of COVID-19. However, diagnosis of the oral mucosal lesions did not appear to be consistent. Most of the studies were retrospective analyses of medical notes and reviews of hospital episode data, which made robust diagnosis and validation of the lesions difficult. One study was prospective and attempted to validate the diagnosis with examination by oral pathologists and laboratory confirmation. This study further attempted to classify the lesions as COVID-19 disease-related or treatment-related by considering the timing of their appearance and the start of therapies to treat COVID-19.15 They postulated that early oral lesions that demonstrated peripheral thrombosis on histopathological analysis could be a warning sign of possible evolution to severe illness, which was noted in four cases. The same study also reported on the modality of treatment offered for the lesions, including topical agents such as hyaluronic acid, 2% chlorhexidine for ulcerations, miconazole for patients with cytological diagnosis of candidiasis, and tranexamic acid for local haemorrhage.15

Discussion

This review has revealed several interesting findings that are worthy of discussion. The results have shown that the oral lesions stated above could be manifestations of COVID-19, but it is not possible to differentiate them entirely from lesions that occurred due to treatment of the condition.

Ideally, exploration of the manifestation of a disease would require an exposure group and a control group for comparison. As COVID-19 is a new disease, so far there has not been a large-scale observational study on this topic, and most of the studies appraised lacked a control group (seven were of cross-sectional design and three were case series). We excluded case reports, letters, reviews, and conference abstracts to improve the quality of the review. The language of the publications was restricted to English to ensure that the review was carried out in a timely fashion without any financial implication for language translation services. This, however, may have led to publication bias.

Observational studies should ideally be reported using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines,21 but none of the appraised studies utilised this system. Important information, such as a statement of a null hypothesis, selection criteria, classification of the oral manifestations, and explanation as to how the information was reported and validated, were not uniformly included. A sample size calculation was not carried out in any of the studies and none included a flow diagram to demonstrate the number of subjects.

The number of subjects ranged from three patients to 665, with an age range of 3 months - 78 years. It is important that any study exploring a causal link would need to have a low risk of bias. However, the differing age groups of the patients as well as the varying severity of COVID-19 disease resulted in heterogeneity of the data and a high risk of bias. A large-scale case control or cohort study would be useful to determine the causal link between oral mucosal lesions and COVID-19. Only one study in the review included a comparator group: patients with recurrent aphthous ulceration and COVID-19 compared with patients with COVID-19 without recurrent aphthous ulceration.11 However, as it focused only on recurrent aphthous ulceration, its scope in determining a causal link to various other types of lesions is limited. Nevertheless, the authors stated a strong association between COVID-19 and the condition.11

Although oral lesions appear during the illness with COVID-19, it has not been possible to determine whether they were complications of the disease, or related to medical care or pre-existing medical conditions of the patients. Perhaps in severe cases of COVID-19 when intubation was required, the lack of minimal oral hygiene standards could also have resulted in oral lesions. Other potential confounding factors include trauma secondary to intubation, coexisting medical conditions such as diabetes or immunosuppression, vascular complications, and opportunistic or secondary infections, which may have led to a number of oral manifestations.

Some studies attempted to exclude patients with a history of oral ulceration or coexisting medical conditions to reduce confounding bias, but the lesions could have been a result of the treatment they had received, which again was not possible to determine.22 It is also important to bear in mind that COVID-19 was more severe in the older age group. This group may have higher levels of associated comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, or other cardiovascular illnesses, the treatment of which may have resulted in the oral lesions.

Among the studies appraised, three reported data on the paediatric population.10, 13, 14 This group differed in the presentation of the disease with most cases presenting with mild symptoms, and some with a severe systemic hyperinflammatory status. A systemic hyperinflammatory reaction to the viral illness appears to be particularly associated with this group, but oral factors may still be a presenting feature of COVID-19 in children.23

Conclusion

This systematic review has identified several types of oral mucosal lesions that may be associated with COVID-19, although the causal link is difficult to establish on the basis of the studies published so far. We have demonstrated the need for further well-designed, large-scale, prospective cohort or case control studies to establish the causal link of oral lesions and COVID-19. Multicentre studies may facilitate a large number of subjects, and consideration should be given to the validity of the diagnosis of the lesions. Standardised reporting of the type of lesion and the location would be useful. It would also be helpful if studies reported on the management of oral mucosal lesions in COVID-19 patients.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement/confirmation of patients’ permission

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms F Mina Shaibatzadeh of the University of Southampton Health Sciences Library for carrying out electronic searches and supplying the list of articles.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Available from URL: https://covid19.who.int (last accessed 16 August 2021).

- 2.Sakaguchi W., Kubota N., Shimizu T., et al. Existence of SARS-CoV-2 entry molecules in the oral cavity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6000. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amorim Dos Santos J., Normando A.G., Carvalho da Silva R.L., et al. Oral manifestations in patients with COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Dent Res. 2021;100:141–154. doi: 10.1177/0022034520957289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS UK. Main symptoms of coronavirus (COVID-19). Available from URL: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/symptoms/main-symptoms/ (last accessed 16 August 2021).

- 5.Iranmanesh B., Khalili M., Amiri R., et al. Oral manifestations of COVID-19 disease: a review article. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34 doi: 10.1111/dth.14578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatahzadeh M. Oral manifestations of viral infections. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhujel N., Zaheer K., Singh R.P. PROSPERO; 2021. Oral lesions in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. CRD42021245738. Available from URL: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021245738 (last accessed 16 August 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munn Z., Moola S., Riitano D., et al. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abubakr N., Salem Z.A., Kamel A.H. Oral manifestations in mild-to-moderate cases of COVID-19 viral infection in the adult population. Dent Med Probl. 2021;58:7–15. doi: 10.17219/dmp/130814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falah N.U., Hashmi S., Ahmed Z., et al. Kawasaki disease-like features in 10 pediatric COVID-19 cases: a retrospective study. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz J., Yue S. Increased odds ratio for COVID-19 in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2021;50:114–117. doi: 10.1111/jop.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidan V., Koyuncu H., Akin O. Oral lesions in Covid 19 positive patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.102905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halepas S., Lee K.C., Myers A., et al. Oral manifestations of COVID-2019-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: a review of 47 pediatric patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardellini E., Bondioni M.P., Amadori F., et al. Non-specific oral and cutaneous manifestations of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in children. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021 doi: 10.4317/medoral.24461. (online ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Favia G., Tempesta A., Barile G., et al. Covid-19 symptomatic patients with oral lesions: clinical and histopathological study on 123 cases of the University Hospital Policlinic of Bari with a purpose of a new classification. J Clin Med. 2021;10:757. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascitti H., Bonsang B., Dinh A., et al. Clinical cutaneous features of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 hospitalized for pneumonia: a cross-sectional study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martín Carreras-Presas C., Amaro Sánchez J., López-Sánchez A.F., et al. Oral vesiculobullous lesions associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Oral Dis. 2021;27 Suppl 3:710–712. doi: 10.1111/odi.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandão T.B., Gueiros L.A., Melo T.S., et al. Oral lesions in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: could the oral cavity be a target organ? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;131:e45–e51. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz Tapia R.O., Peraza Labrador A.J., Guimaraes D.M., et al. Oral mucosal lesions in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Report of four cases. Are they a true sign of COVID-19 disease? Spec Care Dent. 2020;40:555–560. doi: 10.1111/scd.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinadinos A., Shelswell J. Oral ulceration and blistering in patients with COVID-19. Evid Based Dent. 2020;21:49. doi: 10.1038/s41432-020-0100-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freni F., Meduri A., Gazia F., et al. Symptomatology in head and neck district in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a possible neuroinvasive action of SARS-CoV-2. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cant A., Bhujel N., Harrison M. Oral ulceration as presenting feature of paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome associated with COVID-19. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]