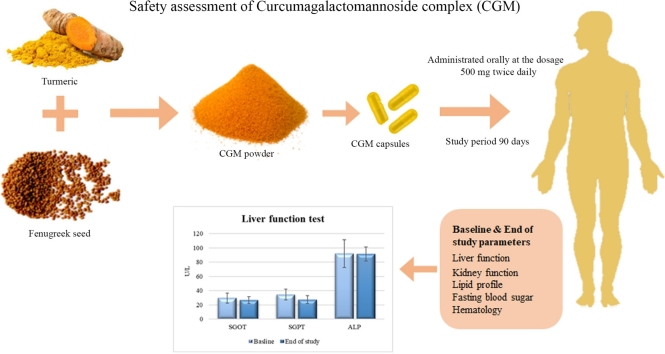

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Bioavailability, Curcumin, Curcumin-galactomannoside complex, CurQfen, Hepatotoxicity, Human study

Highlights

-

•

CGM did not cause adverse effects or significant variations in clinical parameters.

-

•

Liver and renal function markers were in normal range after CGM supplementation.

-

•

CGM was proved to be devoid of adjuvants, synthetic curcumin and contaminants.

-

•

CGM has 100 % natural clean label status comprising vegan, allergen-free ingredients.

Abstract

Recently, there is a growing concern about the use of curcumin supplements owing to a few reported hepatotoxicity related adverse events among some of the long-term consumers. Even though no clear evidence was elucidated for the suspected toxicity, the addition of adjuvants that inhibits body’s essential detoxification pathways, adulteration with synthetic curcumin, and presence of contaminants including heavy metals, chromate, illegal dyes, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and pyrrole alkaloids were suggested as plausible reasons. Considering these incidences and speculations, there is a need to critically evaluate the safety of curcumin supplements for prolonged intake. The present study is an evaluation of the safety of curcumin-galactomannoside complex (CGM), a highly bioavailable curcumin formulation with demonstrated high free curcuminoids delivery. Twenty healthy human volunteers were evaluated for toxic manifestations of CGM when supplemented with 1000 mg per day (∼380 mg curcuminoids) for 90-days. CGM supplementation did not cause any adverse effects or clinically significant variations in the vital signs, hematological parameters, lipid profile and renal function markers of the volunteers, indicating its safety. Liver function enzymes aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and bilirubin were in the normal range after 90-day supplementation of CGM. In summary, no adverse effects were observed under the conditions of the study. CGM can be considered as a safe curcumin supplement for regular consumption and is devoid of any adulterants or contaminants.

1. Introduction

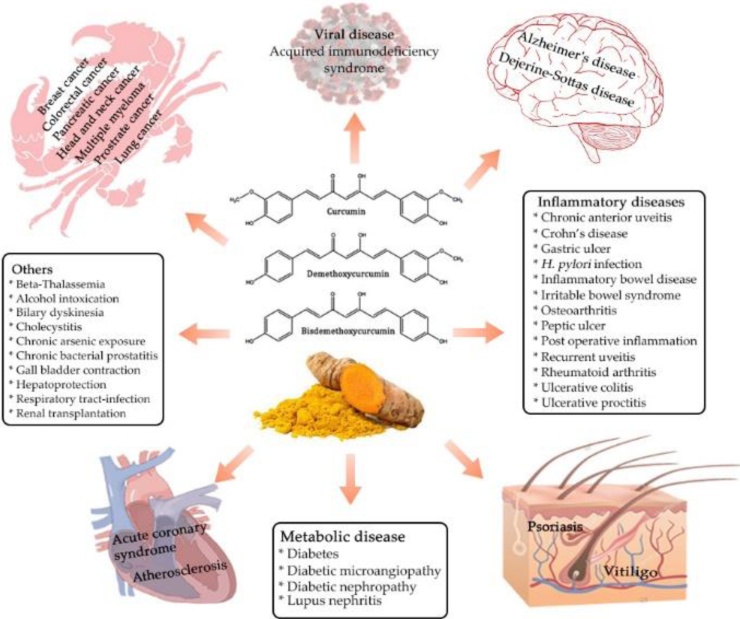

Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L.) is an age-old Asian Spice with more than 5000 years of history of usage in Indian traditional systems of medicine. An average of 1.5–2.5 g of turmeric was estimated to be consumed by Asians in their daily diet; which may correspond to about 60–100 mg of curcuminoids, the chief biologically active principle and yellow pigment of turmeric [1,2]. Curcumin was first isolated from turmeric rhizomes in 1815 by the German scientists Vogel and Pelletier and its chemical structure was elucidated by Milobedeska and Lampe in 1910 as (1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione [3]. The first human clinical trial of curcumin was reported by Oppenheimer in 1937 for biliary disease and later its antibacterial property was identified by Schraufstatter and Bernt in 1949 [4,5]. The modern interest in curcumin was initiated with the early reports and human study by Kuttan et al. on its anti-cancer properties [6,7], and hypolipidemic effect [8]. Since then, thousands of in vitro and in vivo studies have been reported on its pleiotropic mechanism of action and therapeutic potential against a wide range of disease conditions including cancer and Alzheimer’s [1] (Fig. 1). There were about 120 clinical trials performed on curcumin by 2017 and out of which 17 double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials and 27 other trials have testified its safety and potential therapeutic benefits against various clinical conditions [9].

Fig. 1.

Pharmacological activities of curcumin.

Industries have standardized solvent extraction techniques to produce 95 % pure curcuminoids from dried turmeric rhizomes, with a definite ratio of three polyphenolic molecules [curcumin or diferuloylmethane (72–80 %), demethoxycurcumin (DMC) (12–15 %) and bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) (2–5%)], commonly referred to as ‘curcumin’ (Fig. 1). Chemically, curcumin is an α, β-unsaturated diketone moiety with two phenolic groups. These functional groups makes the curcumin highly reactive, involving in proton donation and self-oxidation, reversible or irreversible nucleophilic addition (Michael reaction), hydrolysis, reductive degradations and enzymatic reactions [2]. These chemical properties contributed to the multi-targeted mechanisms of action of curcumin through interaction with a wide range of membrane proteins, signaling molecules, free radicals and transcription factors [1,2]. The structural features also contributed to the lability, insolubility, poor absorption, rapid biotransformation and fast elimination of curcumin from systemic circulation [2]. Thus, curcumin can be considered as a class IV BCS molecule (Biopharmaceutics classification system) with interesting pharmacodynamics, but poor pharmacokinetics.

The poor oral bioavailability is one of the major limitation of curcumin in its translation to a potential therapeutic or functional molecule [10,11]. Various methods have been developed to enhance the bioavailability of curcumin and many of those formulations are available as dietary supplements or nutraceuticals. As per the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classification, turmeric is Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) and the consumption of curcumin at 3 mg/Kg body weight is also suggested [12]. The extreme safety profile of curcumin has also been established by numerous pre-clinical and clinical studies at 8000–12000 mg/day dosage [13,14]. However, recently there is a mounting interest on the hepatotoxicity of enhanced bioavailable curcumin formulations, owing to a few cases of acute cholestatic hepatitis among some of the long term users and subsequently one of the supplement (Nutrimea's Curcuma Liposomal & black pepper) was recalled by Belgium’s Federal Agency for Food Chain Safety [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. Though no clear evidence were elucidated, various plausible reasons including the use of adjuvants that inhibit body’s essential detoxification pathways with piperine, enhanced bioavailability, adulteration with synthetic curcumin and other toxic food contaminants were suggested for reported toxicity [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]].

CGM is a highly bioavailable curcumin formulation, prepared as a self-emulsifying curcumin-galactomannoside complex using fenugreek galactomannan (soluble dietary fiber) hydrogel scaffold. CGM was standardized to contain not less than 35 % of curcuminoids (sum of curcumin, demethoxy curcumin and bisdemethoxy curcumin) and is commercially available as a nutraceutical under the trademark name CurQfen®. Though CGM was proved to be safe with a no-observable-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) up to 2000 mg/kg b. wt. in rats [25], significantly high bioavailability of free (unconjugated) curcuminoids, improved blood-brain-barrier permeability and its cellular uptake necessitate a thorough evaluation of its potential toxic manifestations [26]. The present study was thus aimed to investigate the safety of CGM in healthy human volunteers, with reference to the liver and other critical organ functions, upon prolonged supplementation (90 days) at its highest recommended dosage (1000 mg; i.e., ∼380 mg curcuminoids per day).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study material

The curcumin-galactomannan complex (CGM) containing two-piece hard-shell gelatin capsules was obtained from M/s Akay Natural Ingredients, Cochin, India along with a detailed certificate of analysis comprising various safety parameters.

2.2. Study design and subject recruitment

The open-label, single-arm, prospective clinical study was conducted at Medistar Hospital & Research Center, Vadodara, Gujarat, India. The subject selection was done among the healthy volunteers who accompanied the patients that visited the outpatient treatment facility of the hospital. The study was performed in strict accordance with the clinical research guidelines of Government of India, following the protocol approved by the registered ethical committee (LCBS-AK-54 dated 11/01/2020). Written informed consent was acquired from all the study participants in agreement with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was carried out for 90 days, including 2 visits and was registered in the clinical trial registry of India (CTRI/2020/03/023985 dated 16/03/2020).

During the first visit (day 1), 34 healthy volunteers (both male and female) of age 18–50 years, were screened for the eligibility criteria (Table 1). Physical examination of the participants was performed and abdominal ultrasound scanning was also done if demanded by the physician. Twenty healthy volunteers meeting all the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled for the study and the details of the concomitant and previous medical history, demographic details, anthropometric measurements and vital signs were collected. The participants were requested to arrive at the study site in the fasted state and blood samples were collected for laboratory assessment. After the initial assessments were completed, all the participants were provided with the container carrying the study material and were requested to consume one capsule (500 mg) orally, twice a day (before breakfast and dinner) for 90 days. The participants were not allowed to consume any supplements containing turmeric, other than their regular food, during the study period and were instructed to maintain their usual dietary and exercise practices without any major change in the lifestyle. A subject diary was provided to all the participants for documenting the time of product consumption, experienced discomforts, adverse events, or requirement of medical attention during the study period. Study participants were asked to return to the study site in the fasting state after 90 days of treatment with the study medication container and the completed subject diary to measure compliance and tolerance. At visit 2 (Day 90), vital signs and anthropometric measurements were recorded again. Participants were also monitored for discomforts or adverse reactions through telephonic follow-ups and short message services on weekly basis.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria of the study.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Both male and female subjects of age 18–50 years | Subjects suffering from any chronic health conditions (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, heart, thyroid and liver disease) requiring medical treatment |

| Subjects having body weight > 50 Kg | History of chronic metabolic disease, psychiatric illness, drug abuse, smoking, abuse/addiction to alcohol, eating disorder such as bulimia or binge eating, endocrine abnormalities including stable thyroid disease, cardiovascular surgery / history of any major surgery |

| Women of child bearing potential practicing an acceptable method of birth control as judged by the investigator(s) [such as condoms, foams, jellies, diaphragm, intrauterine device, oral or long acting injected contraceptives] from at least 2 months prior to study entry and through the duration of the study; or postmenopausal for at least 1 year, surgically sterile (bilateral tubal ligation, bilateral oophorectomy, or hysterectomy has been performed on the subject); with a negative urine pregnancy test. | Diagnosis of any other clinically significant medical condition which in opinion of investigator may jeopardize subject’s safety and preclude trial participation |

| Subjects who have no evidence of any underlying disease | Known HIV or Hepatitis B positive or any other immuno-compromised state |

| Must be willing and able to give informed consent and comply with the study procedures | Subjects allergic to herbal products |

| Currently participating or having participated in another clinical trial during the last 1 month prior to the beginning of this study | |

| Any additional condition(s) that in the investigator’s opinion would warrant exclusion from the study or prevent the subject from completing the study |

2.3. Safety analysis

The development of adverse reactions was scrutinized daily, using a non-validated questionnaire that describes the earlier reported adverse effects upon curcumin usage. Study participants were also requested to note down any changes from the regular food or water intake, variation in sleep pattern, incidence of gastrointestinal disturbances, nausea and headache in the subject diary. Safety of the repeated dosage of CGM was evaluated by reviewing the variation in anthropometric parameters, vital signs, hematological and clinical parameters from baseline to end of the study. Blood samples were collected at fasting stage on both the visits for the evaluation of fasting blood sugar (FBS), lipid profile, complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests [aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and bilirubin (total and direct)] and renal function tests [serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)]. Primary safety endpoints include changes in the liver function parameters from the baseline to the end of the treatment. Secondary safety endpoints included abnormal physical examination results and vital signs, clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters (CBC, renal function tests, fasting blood sugar and lipid profile), and any incidence of adverse events.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Version 26 software. Mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables were reported accordingly. Intragroup comparisons were done using paired sample t-test and the ‘P’ values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of CGM

Chemical, physical and microbial analysis results of CGM capsules used in the present study are depicted in Table 2. HPLC analysis showed that each 500 mg capsule contains 38.4 % (192 mg) total curcuminoids (157.75 mg curcumin, 29.5 mg demethoxycurcumin, and 5.375 mg bisdemethoxycurcumin) and debittered fenugreek dietary fiber rich in galactomannans in a 35:65 (w/w) ratio, as a water-dispersible granular powder, with a tap density of 0.64 g/mL, capable of forming self-emulsifying colloidal solutions. CGM was found to be free from various food contaminants which are previously reported in various turmeric products. All the food safety parameters, including residual solvents, heavy metals, illegal dyes, lead chromate, pesticides, genetically modified organisms (GMO), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), allergens, microbial contamination, and mycotoxins were found to be within the safe limits as recommended by food safety standards of major regulatory bodies such as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) (Table 2). Isotopic analysis (14C) established that the material is 100 % natural and free from synthetic additives including synthetic curcumin, dyes, emulsifiers, and excipients.

Table 2.

Certificate of analysis of CGM used in the present study.

| Parameters (test method) | Results |

|---|---|

| Physical characteristics | |

| Colour | Golden yellow to orange |

| Appearance | Free flowing granular powder |

| Particle size | 20−100 mesh |

| Solubility | Dispersible in water, insoluble in alcohol |

| Bulk density | 0.55 g/mL |

| Tap density | 0.64 g/mL |

| Chemical characteristics | |

| Total curcuminoids content (HPLC) | 38.4 % |

| Curcumin | 31.55 % |

| Demethoxy curcumin | 5.9 % |

| Bis demethoxy curcumin | 1.075 % |

| Moisture content (%) | 2.6 % |

| Residual solvents (USP 30/NF 25 < 467 > ) | |

| Acetone | 13 ppm |

| Ethanol | 45 ppm |

| Heavy Metals (AAS method AOAC) | |

| Lead | 0.3 ppm |

| Mercury | Not detected |

| Cadmium | Not detected |

| Arsenic | Not detected |

| Illegal dyes (LCMS/MS) | |

| Sudan I | < 10 μg/kg |

| Sudan II | < 10 μg/kg |

| Sudan III | < 10 μg/kg |

| Sudan IV | < 10 μg/kg |

| Para red | < 20 μg/kg |

| Rhodamine B | < 10 μg/kg |

| Lead chromate (IS 3576: 2010) | Negative |

| Pesticides | |

| IR0XF IR Dithiocarbamates as CS2 (EASI-CHE-SOP-62) | Not detected |

| IR60E IR Pesticides (EASI-CHE-SOP-21) | Not detected |

| IR60 F IR Pesticides (EASI-CHE-SOP-21) | Not detected |

| Genetically modified organisms (GMO) (EF_GI_GMO_PR_02, PCR) | |

| IRI4J IR 35S promoter | Negative |

| IRI4K IR NOS terminator | Negative |

| IR14 L IR FMV promoter | Negative |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) (EASI-CHE-SOP-21) | |

| Benz(a)anthracene | < 0.5 μg/kg |

| Benzo(a)pyrene | < 0.5 μg/kg |

| Benzo(a)fluoranthene | < 0.5 μg/kg |

| Chrysene | < 0.5 μg/kg |

| Sum of 4 PAH | < 0.5 mg/kg |

| Allergens | |

| IR204 IR Gluten (EASI-MB-SOP-34) | < 5.0 mg/kg |

| Microbiology | |

| Total plate count (FDA BAM Ch 3) | Conforms (< 3000 cfu/g) |

| Yeast & Mould (FDA BAM Ch 18) | Conforms (< 100 cfu/g) |

| E. coli (FDA BAM Ch 4) | Conforms (Absent/g) |

| Coliforms (FDA BAM Ch 4) | Conforms (< 3 MPN/g) |

| Salmonella sp. (FDA BAM Ch 5) | Conforms (Absent/25 g) |

| Mycotoxins | |

| B1 + B2 & G1 + G2 (HPLC ASTA) | Conforms (< 4.0 ppb) |

| Aflatoxin B1 (HPLC ASTA) | Conforms (< 2.0 ppb) |

| Ochratoxin (Vicam method, AOAC approved) | Conforms (< 15 ppb) |

| Radiocarbon & stable isotope ratio analysis | |

| 14C activity (± 1σ) | 13.73 ± 0.07 dpm/g C |

| δ13C (± 1σ) | −28.48 ± 0.12 parts per mil |

| δD (± 1σ) | −52 ± 1 parts per mil |

3.2. Patient recruitment

Out of 34 healthy volunteers screened for suitability for inclusion, 20 subjects were enrolled for the study. Twelve subjects were eliminated for not satisfying the eligibility criteria and two subjects were not willing to give the consent. All the 20 participants completed the study by satisfying the study conditions.

3.3. Vital signs, anthropometric and demographic characteristics

The study participants included 11 males and 9 females with an average age of 31.32 ± 9.3. The BMI of all the participants was in normal range at the time of inclusion and is maintained throughout the study period. There was no significant variation in the pulse, systolic and diastolic blood pressure of the participants from baseline to end of the study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in vital signs, demographic, anthropometric and biochemical parameters from baseline to end of the study.

| Parameters (unit) | Baseline | 90th day |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 31.32 ± 9.32 | – |

| Male | 11 (55 %) | – |

| Female | 9 (45 %) | – |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.59 ± 1.25 | 24.43 ± 1.29ns |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 121.5 ± 8.13 | 117.5 ± 7.86ns |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77.5 ± 4.44 | 75.0 ± 6.07ns |

| Pulse | 82.8 ± 5.93 | 85.3 ± 8.24ns |

| Fasting Blood Sugar (mg/dL) | 93.11 ± 7.05 | 88.39 ± 7.0** |

| AST (U/L) | 29.6 ± 7.17 | 26.67 ± 4.71ns |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.39 ± 7.59 | 27.28 ± 5.51*** |

| ALP (U/L) | 92.08 ± 19.45 | 91.33 ± 9.96ns |

| GGT (U/L) | 34.46 ± 6.89 | 28.81 ± 4.72* |

| LDH (U/L) | 241.21 ± 26.73 | 240.19 ± 21.86ns |

| Bilirubin (total) (mg/dL) | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 0.43 ± 0.12ns |

| Bilirubin (direct) (mg/dL) | 0.26 ± 0.10 | 0.26 ± 0.08ns |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.11ns |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 13.36 ± 1.38 | 13.01 ± 2.15ns |

| TC (mg/dL) | 175.63 ± 13.64 | 165.12 ± 10.47** |

| TG (mg/dL) | 102.56 ± 19.05 | 93.83 ± 12.63ns |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 107.76 ± 12.12 | 96.77 ± 17.16* |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 47.36 ± 3.29 | 48.08 ± 4.80ns |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | 20.51 ± 3.81 | 18.77 ± 2.52ns |

| TLC (cumm) | 7475 ± 1413.79 | 7705 ± 1445.31ns |

| RBC (million/cumm) | 4.93 ± 0.15 | 4.79 ± 0.35ns |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.26 ± 0.43 | 13.3 ± 0.89ns |

| HCT (%) | 41.16 ± 1.84 | 39.89 ± 2.82ns |

| MCV (fL) | 83.39 ± 3.25 | 83.32 ± 4.01ns |

| MCH (pg) | 26.92 ± 0.83 | 27.8 ± 1.54* |

| MCHC (%) | 32.25 ± 1.22 | 32.88 ± 1.9ns |

| Platelet Count (Lakhs/cumm) | 2.92 ± 0.51 | 2.93 ± 0.43ns |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, nsP > 0.05 for 90th day versus baseline performed using paired sample t-test; BMI, body mass index, AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triacylglycerol; LDL, low-density lipoproteins (mg/dl); HDL, high-density lipoproteins; VLDL, very low-density lipoproteins; TLC, total leucocyte count; Hb, haemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration.

3.4. Safety measurements

None of the study participants showed any serious adverse events or side effects. The comparative results of the hematological and biochemical parameters are given in Table 3. It was observed that liver function tests (AST and ALP) as well as renal function tests (serum creatinine and BUN) of the participants expressed no significant variation from the baseline to the end of the study. Though within the normal reference range, there was a significant reduction in the levels of liver enzymes ALT (P ≤ 0.001) and GGT (P = 0.11) from baseline to end of the study. Renal function parameters including BUN and creatinine levels were found to be in normal range after 90 day’s CGM supplementation. Similarly, all the hematological parameters were conserved in the normal range. There was no significant change observed from baseline to the end of the study, except in the case of MCH which indicated a slight increase (P = 0.22). Fasting blood sugar levels were also maintained in the normal range throughout the study period for all the participants (P = 0.003). A moderate change in the lipid profile including a significant reduction in the TC (P = 0.008) and, low-density lipoproteins (LDL) (P = 0.010) levels were observed at the end of the study. None of the participants reported any change in the food-water intake or sleep pattern. Gastrointestinal disturbance due to the CGM supplementation was not reported in any of the participants during the study period, except one case of meteorism and flatulence.

4. Discussion

The current study evaluated the safety of CGM among healthy human volunteers when supplemented at 500 mg × 2 /day for 3 months. The study assumes high significance in the context of some recent reports on the hepatotoxic effects of a few enhanced bioavailable curcumin supplements. The bioavailable formulations of curcumin may be generally categorized into three generations. In the very first generation (C3-complex/Bioperine® and BCM-95®), significant amounts of adjuvants such as black pepper extract (piperine) or turmeric oil were added to inhibit body’s essential detoxification enzymes (including UDP-glucuronyltransferase, cytochrome P450, hepatic aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase and mixed-function oxygenases) [27]. In the second generation, methods were employed to enhance the solubility of curcuminoids with the usage of synthetic emulsifiers including polysorbates, polyethoxylated hydrogenated castor oil (eg: Novasol®, BioCurc® and Hydrocurc®), phospholipid complexes (eg: Meriva®), carbohydrate complexes (eg: Cavacurcmin® with Cyclodextrin) and water-dispersible forms employing the principles of nano-preparations, and spray drying (eg: Theracurmin®, CurcuWIN® and Turmipure GOLD®). Though these formulations were reported to enhance the plasma curcuminoids levels mainly as their conjugated metabolites (glucuronides and sulfates), many studies have reported that these conjugated metabolites did not possess significant biological effects as they are big water-soluble molecules with rapid renal elimination, minimal membrane permeability and limited blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability [28,29]. Hence the delivery of curcumin as unconjugated natural forms (free form) into the circulation is crucial in achieving the maximum therapeutic benefits. The third-generation curcumin formulations (Longvida® and CurQfen®) have addressed the problem of ‘free’ curcuminoids bioavailability and hence the membrane permeability and cellular uptake without using synthetic emulsifiers such as polysorbates.

CurQfen® (CGM) is a 100 % natural and food-grade formulation of curcumin with fenugreek galactomannans (soluble dietary fiber). CGM was recognized to have high free curcuminoid absorption, enhanced BBB-permeability and better tissue distribution [30,31]. Once swell in the gastrointestinal tract, CGM has been shown to act as a self-emulsifying hydrogel with high mucoadhesive character, capable of delivering amphiphilic colloidal curcumin particles that can be absorbed quickly. CGM has already demonstrated its superior efficacy in a relatively low dosage [[32], [33], [34]], with improved brain bioavailability as revealed by its influence on brain waves [35], radioprotective [36] and neuroprotective effects [37,38]. CGM was reported to exhibit 45-fold enhancement in the bioavailability of free curcuminoids and 270-fold enhancement in the bioavailability of total curcuminoids (sum of conjugated and unconjugated), when compared to an equivalent dose of unformulated standard curcuminoids with 95 % purity [31]. CGM expressed longer circulation half-life (T1/2) of 3.7 h with a sustained plasma concentration of 0.090 μg/mL even after 12 h of ingestion (C12). Moreover, CGM was found to deliver significantly high levels of free curcuminoids even at a relatively low single dose of 250 mg with a maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of around 300 ng/mL. Tandem mass spectrometric measurements have further revealed high free curcuminoids to conjugated curcuminoids ratio in plasma, indicating the preferential absorption of the highly active free form of curcumin (> 60 %) [31]. Thus, CGM can be considered as the third generation bioavailable curcumin in terms of its 100 % natural status, water-based manufacturing process, organic certification, improved pharmacokinetics and ‘free’ curcuminoids bioavailability [31].

In the present study, despite its improved pharmacokinetics, CGM did not induce toxic manifestations, adverse effects or clinically relevant variations in vital signs, hematological or clinical parameters, when supplemented with 500 mg × 2/day for 90 days in healthy volunteers. The absence of clinically relevant deviations in the hepatic or renal parameters indicated the safety of liver and kidney upon CGM supplementation. Lipid profile of the volunteers was also found to be in the normal range, indicating the non-toxic effects of CGM in the metabolism of fat. The usage of relatively high dosage of enhanced bioavailable curcumin supplements and subsequent high systemic absorption have been assumed to be a reason for the experienced hepatotoxicity in very few reported cases. Yet another possibility is due to the adulteration with low priced synthetic curcumin, synthetic dyes and other food contaminants. CGM is free from all the common contaminants and adulterants as per the FDA/EFSA norms when examined by approved analytical methods (Table 2). Carbon isotopic (14C) analysis was employed as a tool to prove the absence of adulteration with various agents and solvents, principally, synthetic curcumin, excipients, dyes, or emulsifiers. The possibility of contamination from pesticides, residual solvents, PAH, PA, dioxins, synthetic dyes, antibiotics, oxalates, heavy metals, chromates, mycotoxins, and the microbial load was also scrutinized by employing approved analytical methods including GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS, ICP-MS, HPLC and HPTLC.

A detailed search was performed on the reported toxic effects of curcumin using various search engines including PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane library as well as Google Scholar, and the results are summarized in Table 4. A 71-year-old woman, who has been using an unidentified turmeric supplement for 8 months, was reported to develop asymptomatic transaminitis, which later diagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) [39]. However, she had a positive family history of autoimmune disorders and her medical history revealed hypothyroidism (likely Hashimoto’s), Raynaud’s syndrome, hypertension, dyslipidemia, irritable bowel syndrome and diverticulosis. Another 55-year-old woman who was consuming 15 mL of ‘Qunol Liquid Turmeric’ supplement (1000 mg of 95 % curcumin with black pepper extract) daily for 3 months was diagnosed with Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) vs AIH. She also had a medical history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and was on several medications including aluminium hydroxide (200 mg), magnesium hydroxide (200 mg), simethicone (20 mg) and levothyroxine (50 μg) [40]. A 55-year-old man who has been taking an undisclosed turmeric supplement for 5 months, was reported to develop asymptomatic transaminitis on a routine checkup [41]. He was also on a long-term medication for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hypertension, gout, and osteoarthritis including Telmisartan, Atenolol and Lercanidipine. Yet another case of a 52-year-old female who has been consuming Ancient Wisdom Modern Medicine® High Potency Turmeric (375 mg curcuminoids and 4 mg black pepper per tablet) along with a flaxseed oil was reported to develop nausea, pruritus and painless jaundice. However, she had the medical history of hospitalization for diclofenac induced liver injury before this incident [41]. Apart from these four major cases, a few more suspected instances were also reported by health authorities condemning curcumin supplement as the cause for hepatotoxicity, mainly in Italian and US populations [15,16,18]. In most of these reported hepatotoxicity cases, the use of one or more concomitant medications or products was identified [18].

Table 4.

Curcumin supplements induced hepatotoxicity - summary of case reports.

| Reference | Age (y), gender & country of the patient | Name of the curcumin supplement used & dosage | Composition of the used curcumin supplement | Duration of usage & reported adverse effect | Medical history of the patient | Concomitant medicines or supplements used | Family medical history | Previously reported incidence of liver disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lukefahr et al., 2018 [39] | 71, female, USA | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | 8 months; asymptomatic transaminitis | Hypothyroidism (likely Hashimoto’s), Raynaud’s syndrome, Osteoarthritis, Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, Irritable bowel syndrome, Diverticulosis | Amlodipine, metoprolol, atenolol, benazepril, levothyroxine, meloxicam, estradiol, loratadine, diphenhydramine, aspirin, calcium, vitamin D, a multi-vitamin, fish oil, a proprietary formulation of alpha-galactosidase and invertase, lysine, alfalfa powder, glucosamine with chondroitin, a proprietary high fibre supplement and a proprietary formulation containing vitamins, minerals, grape seed extract | Segmental mediolytic arteritis or polyarteritis nodosa | A slight isolated elevation in alanine transaminase attributed to the use of statin-containing red yeast rice |

| Lee et al., 2020 [40] | 55, female, NR | Qunol Liquid Turmeric, 15 mL/day |

95 % curcuminoids, black pepper extract, luo han guo (LHG) |

3 months, acute autoimmune hepatitis | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Famotidine 20 mg, aluminum hydroxide- magnesium Hydroxide -simethicone 200 mg-200 mg-20 mg/5 mL of oral suspension- 10 mL by mouth as needed, levothyroxine 50 mg | Not reported | Not reported |

| Luber et al., 2019 [41] | 52, female, Caucasian | Ancient Wisdom Modern Medicine_ High Potency Turmeric, 1 tab/day |

375 mg curcuminoids, 4 mg black pepper extract |

1 month, jaundice with no hepatomegaly or clinical features of chronic liver disease |

Oligoarticular osteoarthritis | Cholecalciferol 50 mcg, ascorbic acid 500 mg, levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine device, flaxseed oil supplement, diclofenac (occasional) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Luber et al., 2019 [41] | 55, male, Italy |

Undisclosed | Undisclosed | 5 months, asymptomatic transaminitis | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hypertension, gout, osteoarthritis | Telmisartan, atenolol, lercanidipine |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 55, female, Caucasian | Turmecur®, 3 tab/day |

400 mg Curcuma longa L. rhizomes dry extract, 90 mg turmeric rhizomes powder | 2 months, hepatitis | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 62, female, Caucasian | Curcuma Complex®, 4 tab./day for the first 5 months and 3 tab./day for the subsequent 3 months |

500 mg Curcuma longa L. dry extract; 100 mg Zingiber officinale L. dry extract; 3 mg black pepper extract; 300 mg cellulose derived fibers; 62 mg stearic derived fatty acids | 8 months, acute yellow atrophy of the liver | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 59, male, Caucasian | Piperina & Curcuma Plus® 4 tab./day |

70 mg Curcuma longa L. rhizomes powder; 7 mg black pepper extract | Unspecified period, acute liver disease | Heart failure and systemic infection | Amiodarone & azithromycin (intravenous) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 45, female, NR | Curcuma Plus 95 % Piperina & Vitamine B1 B2 B6® 2 tab./day |

950 mg curcuminoids, 9.5 mg of piperine; 3.3 mg pyridoxine; 2.8 mg riboflavin, 2.7 mg thiamine |

2 months, acute cholestatic hepatitis | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 68, female, NR | Movart® 1 tab./day |

Curcuma Phytosome® containing 200 mg of Curcuma longa L. rhizomes dry extract titrated in curcuminoids, 400 mg of sunflower phospholipids, 5 mg Echinacea angustifolia root dry extract titrated in alkylamides |

3 months, non-pancreatic cholestatic hepatitis | Postmenopausal osteoporosis | Denosumab 60 mg/mL (one injection every 6 months) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 56, female, Caucasian | Curcuma Plus 95 % Piperina & Vitamine B1 B2 B6® 2 tab./day |

950 mg of curcuminoids, 9.5 mg of piperine; 3.3 mg pyridoxine; 2.8 mg riboflavin, 2.7 mg thiamine | 1 month, acute hepatitis | Not reported | Bisoprolol 1.25 mg/day | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lombaridi et al., 2020 [18] | 61, female, NR | W-Curcuma+®, 1 tab./day |

500 mg Curcuma longa L. rhizomes dry extract 95%; 200 mg Boswellia serrata Roxb. gum-resin dry extract 65%; 20 mg Lithothamnion calcareum seaweed thallus |

2 weeks, acute cholestatic hepatitis. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Abdallah, 2019 [54] | 51, female, USA | Brand name undisclosed, 1 cap./day |

400 mg turmeric powder, 50 mg turmeric extract, 50 mg organic ginger powder | 2 months, elevated liver enzymes | Multiple environmental allergies, allergic rhinitis, anxiety | Sertraline 25 mg/day, multivitamins, primrose oil & omega 3 dietary supplements, acetaminophen (occasionally); cetirizine and methylprednisolone |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Costa, 2018 [55] | 67, male, Caucasian | Turmeric 15 g/day |

15 g turmeric/day | 38 days, asthenia, anorexia, jaundice, choluria | pulmonary emphysema, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, benign prostatic hyperplasia, lung cancer | Metformin + sitagliptin, alfuzosin, atorvastatin, budesonide, formoterol, tiotropium bromide, paclitaxel (165 mg/m2), carboplatin (275 mg/m2) (BSA: 1.82 m2); Milk thistle (900 mg with 13.5 mg silymarin/day), vitamins and minerals (vitamin-C 60 mg, vitamin-E 20 mg, vitamin-A 1.5 mg, zinc sulphate 5.5 mg and selenium 50 μg); chlorella (520 mg/day), colostrum (650 mg/day) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Fernández-Aceñero, 2019 [56] | 78, female, Spain | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | Long term usage, acute liver injury | Osteoarthritis | Etoricoxib (60 mg/day) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Suhail, 2019 [16] | 61, female, USA | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | 6 months, polycystic liver disease | Not reported | Naproxen, ergocholecalciferol | Not reported | Not reported |

Out of millions of consumers using various turmeric derived products for many years, only a few expressed toxic manifestations, indicating the involvement of other personalized reasons. None of these reported cases confirm solid evidence for curcumin linked hepatic injury or liver failure and a careful examination of cases provides solid association of polypharmacy, prior history of hypertension and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, extensive use of diclofenac or blood thinners among the reported subjects. Furthermore, curcumin has already been proved to have significant hepatoprotective effect in numerous preclinical and clinical studies [42,43]. In an earlier reported pilot clinical study, a short term supplementation of curcumin was found to express a significant reduction in liver fat content (78.9 %), liver transaminases and lipid profile of subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [44]. Curcumin was also found to reduce heavy metal-induced hepatotoxicity by preventing histological injury, lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction and maintaining liver antioxidant enzyme status [45]. Supplementation of CGM at 250 mg × 2 /day has been shown to attenuate the elevated liver function enzyme markers among chronic alcoholics in 28 days [33]. Further studies on alcohol-induced cirrhotic model of rats confirmed the hepatoprotective effect of CGM through modulation of TLR4/MMP expression and hepatic cellular regeneration [46].

The presence of synthetic curcumin, lead content, residual solvents belonging to toxicity class 1 and 2 were identified in many of the turmeric dietary supplements available in the US market [23]. The synthetic curcumin may contain non-food grade petroleum-derived residual solvents or ions such as boron that used as catalysts in the reaction and none of the countries allow its usage in Nutraceuticals, Dietary supplements and Functional foods [19]. Adulteration with synthetic dyes such as lead chromate and metanil yellow (to enhance the vibrant yellow color) were also reported in the turmeric products [20,21]. Nearly thirteen brands of lead-contaminated turmeric have been voluntarily recalled since 2011, following a few cases of childhood lead poisoning reported in the United States [47]. Other possible causes of contamination include the presence of pesticides, heavy metals, mycotoxins, PAH, pyrrole alkaloids (PAs), oxalates and antibiotics [21,24]. The presence of the anti-inflammatory drug Nimesulide was also detected in one of the curcumin supplements [48]. Another factor that was observed in many of the reported hepatotoxicity cases is the concomitant use of black pepper extract or piperine along with a high dose of curcumin (nearly 1–1.5 g per day) for a longer duration (Table 4). So, a detailed investigation is warranted, since agents such as black pepper extract increase the bioavailability of curcumin by inhibiting hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes and hence are capable of disturbing the body’s detoxification process [27].

Besides the suspected hepatotoxicity, possibility of a few other side effects including the anti-thrombotic effect (when supplemented along with blood thinners) [49], the incidence of diarrhea, nausea, headache, rash, yellow stool [14,50], and induction of anemia [51], were also speculated upon the use of high dosage of curcumin for a long duration. Though a few animal studies have reported the iron-chelating effect of curcumin when administered intragastrically [52], no clinical data are available to date except the case of a 66-year-old physician who consumed six capsules of turmeric extract (538 mg each) daily for few months [51]. However, the subject had undergone preceding treatments for prostate cancer, myopathy and bronchiolitis which include agents that are known to induce anemia, including radiation, androgen depletion therapy and immune-suppressive glucocorticoid prednisone. Hence the incidence of anemia, in this case, cannot be confined to curcumin. In the present study, CGM did not cause clinically relevant deviations in hematological or biochemical parameters. The results of the present study were also in agreement with a short term study (30 days) conducted using 1000 mg CGM per day [53]. Moreover, earlier safety studies have also demonstrated the non-genotoxic or non-mutagenic effect of CGM [25]. A recent study on the radioprotective effects of CGM (100 mg/kg b. wt.) in Swiss albino mice showed no signs of genotoxicity, DNA damage or chromosomal aberrations among CGM treated animals [36].

5. Conclusion

In summary, CGM was found not to cause any toxic manifestations or adverse events when consumed for 90 days at 1000 mg/day dosage (∼380 mg curcuminoids) and hence can be considered as a safe curcumin supplement for long term use. Detailed analysis for food contaminants and synthetic agents using sophisticated analytical instruments (as per the FDA/EFSA approved analytical methods), confirmed that CGM is free from any contaminants, synthetic excipients and emulsifiers or synthetic curcumin. However, for people who are on multiple medications or using NSAIDs/blood thinners, it is highly advisable to consult with a clinician, before consuming any dietary supplement. For people who are extremely anemic, it is prudent to treat the anemia first and make sure they attain enough iron stores before starting a routine curcumin supplementation. It is generally sensible to prefer highly bioavailable forms of curcumin which have proved its therapeutic efficacy in a relatively low dosage of 250–500 mg/day, thereby avoiding any possible side effects. However, it is advisable to avoid curcumin supplements which contain chemicals or adulterants that are capable of influencing the body’s detoxification mechanisms.

Author contribution statement

V.P. is the principal investigator who conducted the study and was involved in the protocol designing, data analysis, and drafting of the article. A.B.K. belongs to a nonprofit research organization that critically evaluated the data and the drafted manuscript. T.P.S., B.M., and I.M.K. belong to the company M/s Akay Natural Ingredients (Cochin, India), who prepared the study drugs, conceived the idea, and approved the protocol. The sponsoring company has no role in the conduction of the study, data analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the article.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors disclose a potential conflict of interest that “CurQfen®” is the registered trademark of M/s Akay Natural Ingredients, Cochin, India, for “CGM”.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank M/s Akay Natural Ingredients, Cochin, India, for providing the study samples and also for the financial support under Spiceuticals® development program (AKAY/SB/R&D/02/2017-19).

Handling Editor Dr. Aristidis Tsatsakis

References

- 1.Kunnumakkara A.B., Bordoloi D., Padmavathi G., Monisha J., Roy N.K., Prasad S., Aggarwal B.B. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174:1325–1348. doi: 10.1111/bph.13621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heger M., van Golen R.F., Broekgaarden M., Michel M.C. The molecular basis for the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin and its metabolites in relation to cancers. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014;66:222–307. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milobedeska J., Kostanecki V., Lampe V. Structure of curcumin, Berichte der dtsch. Chem. Gesellschaft. 1910;43:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oppenheimer A. Turmeric (Curcumin) in biliary diseases. Lancet. 1937;229:619–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)98193-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schraufstätter E., Bernt H. Antibacterial action of curcumin and related compounds [28] Nature. 1949;164:456–457. doi: 10.1038/164456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuttan R., Bhanumathy P., Nirmala K., George M.C. Potential anticancer activity of turmeric (Curcuma longa) Cancer Lett. 1985;29:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(85)90159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuttan R., Sudheeran P.C., Josph C.D. Turmeric and curcumin as topical agents in cancer therapy. Tumori. 1987;73:29–31. doi: 10.1177/030089168707300105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2435036/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soni K.B., Kuttan R. Effect of oral curcumin administration on serum peroxides and cholesterol levels in human volunteers. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1992;36:273–275. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1291482/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heger M. Drug screening: don’t discount all curcumin trial data. Nature. 2017;543:40. doi: 10.1038/543040c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W., Zhai Y., Heng X., Che F.Y., Chen W., Sun D., Zhai G. Oral bioavailability of curcumin: problems and advancements. J. Drug Target. 2016;24:694–702. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2016.1157883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cas M.D., Ghidoni R. Dietary Curcumin: Correlation between Bioavailability and Health Potential. Nutrients. 2019;11:1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu11092147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.21 CFR 182.10 & 182.20 (USFDA); U.S. National Archives and Records Administration’s Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR), (n.d.). https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=5e161355201c7ba351dc3db88b089ee5 &mc=true&node=pt21.3.182&rgn=div5#se21.3.182_110.

- 13.Cheng A.L., Hsu C.H., Lin J.K., Hsu M.M., Ho Y.F., Shen T.S., Ko J.Y., Lin J.T., Lin B.R., Ming-Shiang W., Yu H.S., Jee S.H., Chen G.S., Chen T.M., Chen C.A., Lai M.K., Pu Y.S., Pan M.H., Wang Y.J., Tsai C.C., Hsieh C.Y. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:2895–2900. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11712783/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lao C.D., Ruffin M.T., IV, Normolle D., Heath D.D., Murray S.I., Bailey J.M., Boggs M.E., Crowell J., Rock C.L., Brenner D.E. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bucchini L. The 2019 curcumin crisis in Italy: what we know so far, and early lessons. Planta Med. 2019;85:1401–1410. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3399667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suhail F.K., Masood U., Sharma A., John S., Dhamoon A. Turmeric supplement induced hepatotoxicity: a rare complication of a poorly regulated substance. Clin. Toxicol. 2020;58:216–217. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1632882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2019. Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment; pp. 1–17.https://cot.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/september2019minutesrevised_0_accessibleinabobepro.pdf Review of hepatotoxicity of dietary turmeric supplements TOX/2019/52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lombardi N., Crescioli G., Maggini V., Ippoliti I., Menniti-Ippolito F., Gallo E., Brilli V., Lanzi C., Mannaioni G., Firenzuoli F., Vannacci A. Acute liver injury following turmeric use in Tuscany: an analysis of the Italian Phytovigilance database and systematic review of case reports. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bcp.14460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girme A., Saste G., Balasubramaniam A.K., Pawar S., Ghule C., Hingorani L. Assessment of Curcuma longa extract for adulteration with synthetic curcumin by analytical investigations. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsyth J.E., Nurunnahar S., Islam S.S., Baker M., Yeasmin D., Islam M.S., Rahman M., Fendorf S., Ardoin N.M., Winch P.J., Luby S.P. Turmeric means “yellow” in Bengali: lead chromate pigments added to turmeric threaten public health across Bangladesh. Environ. Res. 2019;179 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bejar E. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) root and rhizome, and root and rhizome extracts. Bot. Adulterants Bull. 2018 www.botanicaladulterants.org [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liva R. Toxic solvent found in curcumin extract. Integr. Med. 2010;9:50–54. https://jusdecurcuma.com/themes/classic-child/assets/img/integration/jus/Toxic-Solvent-Found-in-Curcumin-Extract-2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skiba M.B., Luis P.B., Alfafara C., Billheimer D., Schneider C., Funk J.L. Curcuminoid content and safety-related markers of quality of turmeric dietary supplements sold in an urban retail marketplace in the United States. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018;62 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesh R., Shobha D. Quantitative estimation of aflatoxin and pesticide residues from turmeric (Curcuma longa) as obtained in the selected area of Chamarajanagara and Mysuru districts, Karnataka, ∼ 2858 ∼. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2018;6:2858–2863. https://www.chemijournal.com/archives/?year=2018&vol=6&issue=2&ArticleId=2300&si= [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liju V.B., Jeena K., Kumar D., Maliakel B., Kuttan R., Krishnakumar I.M. Enhanced bioavailability and safety of curcumagalactomannosides as a dietary ingredient. Food Funct. 2015;6:276–286. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00749b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannan R.G., Abhilash M.B., Dinesh K., Syam D.S., Balu M., Sibi I., Krishnakumar I.M. Brain regional pharmacokinetics following the oral administration of curcumagalactomannosides and its relation to cognitive function. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021 doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2021.1913951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mhaske D.B. Role of Piperine as an effective bioenhancer in drug absorption. Pharm. Anal. Acta. 2018;9:1–4. doi: 10.4172/2153-2435.1000591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pal A., Sung B., Bhanu Prasad B.A., Schuber P.T., Prasad S., Aggarwal B.B., Bornmann W.G. Curcumin glucuronides: assessing the proliferative activity against human cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;22:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stohs S. Issues with human bioavailability determinations of bioactive curcumin, biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2019;12:001–003. doi: 10.26717/bjstr.2019.12.002289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnakumar I.M., Maliakel A., Gopakumar G., Kumar D., Maliakel B., Kuttan R. Improved blood-brain-barrier permeability and tissue distribution following the oral administration of a food-grade formulation of curcumin with fenugreek fibre. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;14:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar D., Jacob D., Subash P.S., Maliakkal A., Johannah N.M., Kuttan R., Maliakel B., Konda V., Krishnakumar I.M. Enhanced bioavailability and relative distribution of free (unconjugated) curcuminoids following the oral administration of a food-grade formulation with fenugreek dietary fibre: a randomised double-blind crossover study. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;22 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.01.039. 578–587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas J.V., Smina T.P., Khanna A., Kunnumakkara A.B., Maliakel B., Mohanan R., Krishnakumar I.M. Influence of a low‐dose supplementation of curcumagalactomannoside complex (CurQfen®) in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, open‐labeled, active‐controlled clinical trial. Phyther. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ptr.6907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnareddy N.T., Thomas J.V., Nair S.S., Mulakal J.N., Maliakel B.P., Krishnakumar I.M. A Novel Curcumin-Galactomannoside Complex Delivery System Improves Hepatic Function Markers in Chronic Alcoholics: A Double-Blinded, randomized, Placebo-Controlled Studyi. Bomed Res. Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9159281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell M.S., Berrones A.J., Krishnakumar I.M., Charnigo R.J., Westgate P.M., Fleenor B.S. Responsiveness to curcumin intervention is associated with reduced aortic stiffness in young, obese men with higher initial stiffness. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;29:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khanna A., Das S., Kannan R., Swick A.G., Matthewman C., Maliakel B., Ittiyavirah S.P., Krishnakumar I.M. The effects of oral administration of curcumin–galactomannan complex on brain waves are consistent with brain penetration: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2020.1853410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liju V.B., Thomas A., Das Sivadasan S., Kuttan R., Maliakel B., Krishnakumar I.M. Amelioration of radiation-induced damages in mice by curcuminoids: the role of bioavailability. Nutr. Cancer. 2020 doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1766092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sunny A., Ramalingam K., Das S.S., Maliakel B., Krishnakumar I.M., Ittiyavirah S. Bioavailable curcumin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation and improves cognition in experimental animals. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2021;15:111. doi: 10.4103/PM.PM_307_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sindhu E.R., Binitha P.P., Nair S.S., Maliakel B., Kuttan R., Krishnakumar I.M. Comparative neuroprotective effects of native curcumin and its galactomannoside formulation in carbofuran-induced neurotoxicity model. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;34:1456–1460. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1514401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukefahr A.L., McEvoy S., Alfafara C., Funk J.L. Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis associated with turmeric Detary supplement use. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee B.S., Bhatia T., Chaya C.T., Wen R., Taira M.T., Lim B.S. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with turmeric consumption. ACG Case Reports J. 2020;7 doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luber R.P., Rentsch C., Lontos S., Pope J.D., Aung A.K., Schneider H.G., Kemp W., Roberts S.K., Majeed A. Turmeric induced liver injury: a report of two cases. Case Reports Hepatol. 2019;2019:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2019/6741213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyes-Gordillo K., Shah R., Lakshman M.R., Flores-Beltrán R.E., Muriel P. Liver Pathophysiol. Ther. Antioxidants. Elsevier; 2017. Hepatoprotective properties of Curcumin; pp. 687–704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bulku E., Stohs S.J., Cicero L., Brooks T., Halley H., Ray S.D. Curcumin exposure modulates multiple pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signaling pathways to antagonize acetaminophen-induced toxicity. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2012;9:58–71. doi: 10.2174/156720212799297083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahmani S., Asgary S., Askari G., Keshvari M., Hatamipour M., Feizi A., Sahebkar A. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with curcumin: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phyther. Res. 2016;30:1540–1548. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Niño W.R., Pedraza-Chaverrí J. Protective effect of curcumin against heavy metals-induced liver damage. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014;69:182–201. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohan R., Jose S., Sukumaran S., Asha S., Sheethal S., John G., Krishnakumar I.M. Curcumin-galactomannosides mitigate alcohol-induced liver damage by inhibiting oxidative stress, hepatic inflammation, and enhance bioavailability on TLR4/MMP events compared to curcumin. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019;33 doi: 10.1002/jbt.22315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowell W., Ireland T., Vorhees D., Heiger-Bernays W. Ground turmeric as a source of lead exposure in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2017;132:289–293. doi: 10.1177/0033354917700109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Starling S. 2009. Tainted Turmeric Supplements Linked to Scandinavian Deaths.https://www.nutraingredients.com/Article/2009/03/23/Tainted-turmeric-supplements-linked-to-Scandinavian-deaths# [Google Scholar]

- 49.Health Central . 2018. Medsafe Warning Over Risk of Taking Turmeric With Warfarin | Health Central.https://healthcentral.nz/medsafe-warning-over-risk-of-taking-turmeric-with-warfarin/ [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma R.A., Euden S.A., Platton S.L., Cooke D.N., Shafayat A., Hewitt H.R., Marczylo T.H., Morgan B., Hemingway D., Plummer S.M., Pirmohamed M., Gescher A.J., Steward W.P. Phase I clinical trial of oral curcumin: biomarkers of systemic activity and compliance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:6847–6854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith T.J., Ashar B.H. Iron deficiency Anemia due to high-dose turmeric. Cureus. 2019;11 doi: 10.7759/cureus.3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chin D., Huebbe P., Frank J., Rimbach G., Pallauf K. Curcumin may impair iron status when fed to mice for six months. Redox Biol. 2014;2:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sudheeran S.P., Jacob D., Mulakal J.N., Nair G.G., Maliakel A., Maliakel B., Kuttan R., Krishnakumar I.M. Safety, tolerance, and enhanced efficacy of a bioavailable formulation of curcumin with fenugreek dietary fiber on occupational stress a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:236–243. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdallah M.A., Abdalla A., Ellithi M., Abdalla A.O., Cunningham A.G., Yeddi A., Rajendiran G. Turmeric-associated liver injury. Am. J. Ther. 2020;27:e642–e645. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costa M.L., Rodrigues J.A., Azevedo J., Vasconcelos V., Eiras E., Campos M.G. Hepatotoxicity induced by paclitaxel interaction with turmeric in association with a microcystin from a contaminated dietary supplement. Toxicon. 2018;150:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernández-Aceñero M.J., Ortega Medina L., Maroto M. Herbal Drugs: Friend or Foe? J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2019;9:409–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]