Abstract

Inhibitors of Keap1 would disrupt the covalent interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 to unleash Nrf2 transcriptional machinery that orchestrates its cellular antioxidant, cytoprotective and detoxification processes thereby, protecting the cells against oxidative stress mediated diseases. In this in silico research, we investigated the Keap1 inhibiting potential of fifty (50) antioxidants using pharmacokinetic ADMET profiling, bioactivity assessment, physicochemical studies, molecular docking investigation, molecular dynamics and Quantum mechanical-based Density Functional Theory (DFT) studies using Keap1 as the apoprotein control. Out of these 50 antioxidants, Maslinic acid (MASA), 18-alpha-glycyrrhetinic acid (18-AGA) and resveratrol stand out by passing the RO5 (Lipinski rule of 5) for the physicochemical properties and ADMET studies. These three compounds also show high binding affinity of -10.6 kJ/mol, -10.4 kJ/mol and -7.8 kJ/mol at the kelch pocket of Keap1 respectively. Analysis of the 20ns trajectories using RMSD, RMSF, ROG and h-bond parameters revealed the stability of these compounds after comparing them with Keap1 apoprotein. Furthermore, the electron donating and accepting potentials of these compounds was used to investigate their reactivity using Density Functional Theory (HOMO and LUMO) and it was revealed that resveratrol had the highest stability based on its low energy gap. Our results predict that the three compounds are potential drug candidates with domiciled therapeutic functions against oxidative stress-mediated diseases. However, resveratrol stands out as the compound with the best stability and therefore, could be the best candidate with the best therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: Molecular dynamics, Molecular docking, Density functional theory, Keap1

Molecular dynamics; Molecular docking; Density functional theory; Keap1.

1. Introduction

The imbalance triggered by increase production of free radicals, accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) and reduction in antioxidant status due to factors such as environmental carcinogens, UV radiation, intracellular signaling, metabolic and inflammatory processes cause oxidative stress [1]. Several diseases such as cancer, diabetes and other neurodegenerative diseases have been associated with oxidative stress as a result of DNA damage and cellular impairment; therefore, sustainable antioxidant and cytoprotective mechanisms have been developed by the human cells to combat numerous forms of oxidative stress. These cells possess antioxidant defense mechanism that protects against cellular damage and neutralizes oxidants and electrophiles [2].

Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) is the major regulator of the cellular defense system against oxidative insults [3]. Nrf2 being a 66-kDA Cap ‘n' collar protein having a basic leucine zipper (bzip) DNA binding motif binds to the enhancer sequence in the gene promoter regulatory region thereby implementing optimum regulatory processes towards expressing multiple genes encoding antioxidant protein, detoxifying enzymes and oxidative stress response protein, therefore suppressing oxidative stress and preventing stress related diseases [4, 5]. It has been reported that the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), NADPH quinone oxidase-1 (NQO-1), heme oxygenase-1(HO-1), glutathione-s-transferase (GST) and others which are phase II enzymes or reductants are synthesized as a result of the binding of Nrf2 with other co-transcriptional factors to the cis–regulatory element of the promoter region of its target gene/DNA. This region is called Antioxidant Response Element (ARE)/Electrophile Response Element (ERE) [6, 7]. A major repressor of Nrf2 is a cysteine rich protein known as the human Kelch-like ECH – associated protein (keap-1) which is a 70-kDA protein consisting of over 625 residues of amino acid including 27 cysteine residues [8]. Keap-1 basically comprises of 5 domains; (i) The N-terminal region (NTR) (ii) the broad complex, tramtrac and bric-a-brac (BTB) domain where keap1 interacts with Cullin3-Rbx1 E3 ubiquitin ligase (an evolutionary conserved domain) (iii) Intervening Region (IVR) which is a region rich in cysteine residues (iv) Double Glycine Repeats (DGR) or kelch domain that binds to Neh2 domain of Nrf2 and (v) the C-terminal region (CTR). Recent studies revealed that keap1 promotes polyubiquitination of Nrf2 resulting in its proteasomal degradation [9, 10], therefore, arresting the activity of keap1 leads to an impediment in Nrf2 degradation by ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) causing the accretion and translocation of newly formed Nrf2 to the nucleus where it masterminds the transcription of cytoprotective and antioxidative genes thereby activating the cellular defense system [11].

Ashwini and coworkers reported a computational study using In silico methods (Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics and umbrella sampling) to investigate the atomistic details of keap1-Nrf2 inhibitors. In this study, 100ns of MD simulation using GROMACS software were performed on 4 selected protein-ligand complexes (5FNU_L61, 4XMB_41P, 5CG_51M and 4L7B_1VV). Results showed all other ligands were stable with an RMSD value of less than 1.25Å except 4L7B. Tyr334, Arg415, Ser508, Tyr525 and Tyr572 were identified to be pivotal for hydrophobic interactions while the amino acid residues critical for electrostatic interactions are Ser363,Arg483, Ser508, Gly530, Ser555 and Ser602 [12]. In another research where esculetin's anticancer properties was investigated in PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cell lines (pancreatic cells) through its anti-apoptotic and anti-proliferative potential, it was reported that its anticancer properties was triggered by its antioxidant potential and when molecular docking simulation was implored to examine the interaction between esculetin and Keap1, it was established that esculetin tightly binds Keap1 forming hydrogen bonds (Arg483 and Ala556) and hydrophobic interaction (Ser508, Ser555, Gln530, Gly462 and Ile461). Therefore, it was concluded that esculetin's ARE activation potential through the inhibition of intracellular ROS and anti-cancer prowess must have been orchestrated through the inhibition of Keap1 [13]. The inference from these researches could be that targeting the inhibition of Keap1 might be a therapeutic measure towards the amelioration/treatment of oxidative stress-induced diseases.

Therefore, in this research, we aim at exploiting various in silico methods (ADMET profiling, bioactivity assessment, physicochemical properties, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation with Quantum mechanical-based Density Functional Theory) to indirectly investigate the atomistic mechanism surrounding the Nrf2 activating/antioxidant capacity of various reported fifty (50) antioxidants through their Keap1 inhibitory prowess. The compounds with the best keap1 inhibitory strength/stability could be subjected to further preclinical and clinical investigations that might lead to their adoption as drugs/nutraceuticals for the management/treatment of oxidative stress-mediated diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of target protein

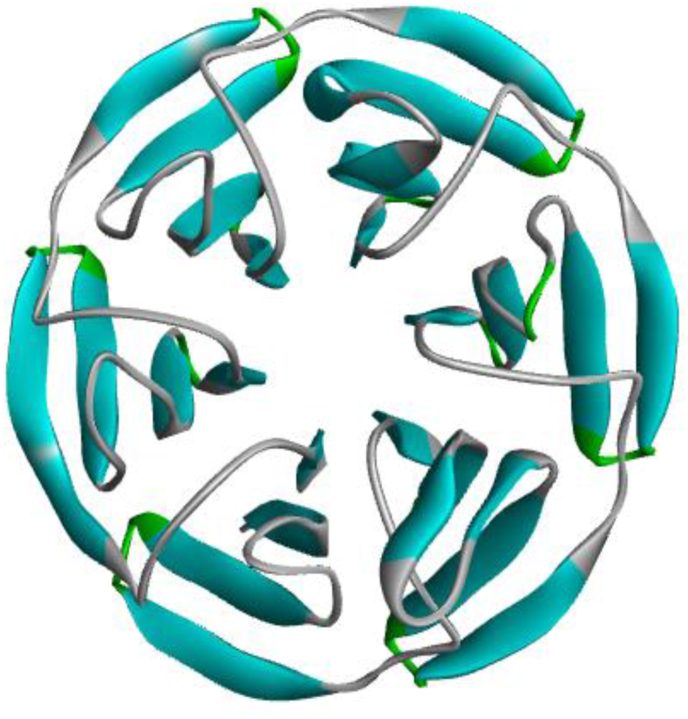

Keap1 protein (PDB ID: 4ZY3) was used as the target protein for this study. The X-ray crystallographic PDB structure of the target protein (PDB ID: 4ZY3) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) (Figure 1) and was treated accordingly using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Software (version 19.1), to prevent unbidden molecular interactions during virtual screening. We defined the binding sites of the target receptors using Computed Atlas for Surface Topology of Proteins (CASTp), and the amino acid residues of the binding sites obtained were validated using the binding pockets and residues reported experimentally for the target proteins using X-RAY crystallography [14]. The amino acid residues reported by CASTp includes Arg326, Tyr334. Ser363, Gly364, Leu365, Ala366, Gly367, Cys368, Val369, Arg380, Asn382, Asn414, Arg415, Ile416, Gly417, Val418, Gly419, Val420, Ile461, Gly462, Val463, Gly464, Val465, Ala466, Val467, Phe478, Arg483, Ser508, Gly509, Ala510, Gly511, Val512, Cys513, Val514, Ser555, Ala556, Leu557, Gly558, Ile559, Thr560, Val561, Ser602, Gly603, Val604, Gly605, Val606, Ala607, Val608.

Figure 1.

Structure of Kelch-like ECH associated Protein-1 (KEAP-1).

Autodock tool-1.5.6 program [15] was used to determine the grids which include the dimension and binding centre of 4ZY3 (-51.176, -3.868, -7.609) for (x, y, z) respectively.

2.2. Preparation of ligands

In this study, fifty (50) reported antioxidants obtained from literatures were used. The SMILES formats of the ligands were retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), an open chemistry database, consisting of substance, compound, and bioassay [16]. These antioxidants include: 18-alpha glycrrhetinic acid (AGA) - CID_73398, Allyl isothiocyanate- CID_5971, Allyl isothiocyanate - CID_5971, 4 -0-caffeolquinic acid - CID_9798666, Alpha-tocotrienol - CID_5282347, Andalusol - CID 188448, Ankaflavin - CID 15294091, Andrographolide - CID_ 5318517, Antroquinonol - CID_24875259, Apigenin- CID_5280443, Benzyl isothiocyanate - CID 2346, Bergenin - CID_66065, Beta-Mercapto ethanol - CID_1567, Butein - CID 5281222, Carnosic acid - CID_65126, Catalposide - CID_93039, Catechol - CID_289, Celastrol - CID_122724, Maslinic acid - CID_73659, Diallyl disulphide - CID_16590, Conchitriol - CID_9929901, Zerumbone - CID_ 5470187, Emodin - CID_3220, Mollugin - CID_ 124219, Fucoxanthin - CID_5281239, Gentisic acid - CID_73062, Forsythiaside - CID_5281773, Verproside - CID_12000799, Cymopol - CID_5386672, Naringenin - CID_439246, Parthenolide - CID_108068, Scopoletin - CID_5280460, Melatonin - CID_896, Licochalcone A - CID _164676, Schisandrin B - CID_108130, Pterostilbene - CID_5280373, Curcumin - CID_969516, Cyanidin 3-0 glucoside-CID_441667, Phenethyl isothiocyanate - CID_16741, Resveratrol - CID_445154, Rutin - CID_5280805, S-allyl-L - cysteine CID_9793905, Salvianolic acid - CID_6451084, Isoliquiritigenin - CID_7427, Withaferin A- CID_265237, Catechin - CID_73160, Galic acid - CID_370, Delta tocotrienol – CID_5282350, Eckol – CID_145937, Gamma tocotrienol – CID_5282349, Lagascatriol – CID_10448831. We converted them to 3-dimensional (3D) structures (.pdb format) for efficient virtual screening process using the online SMILES Translator at https://cactus.nci.nih.gov/translate webserver.

2.3. Molecular docking protocol

Protein Data Bank (PDB) format of the target protein (4ZY3) and ligands were used for the virtual screening while Auto Dock Tools – 1.5.6 was used for the protein optimization, removal of water, adding of polar hydrogen and geisteiger charges. AutoDock Vina [17]was used for the virtual screening on a Linux Ubuntu Operating System.

2.4. Pharmacokinetics (ADMET) and drug-likeness properties evaluation

Molinspiration Online Tool (https://molinspiration.com/) was used to assess the drug-likeliness of the selected antioxidant compounds while properties related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) were evaluated using admetSAR webserver (https://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar2/) [18].

2.5. Density functional theory (quantum mechanics)

The top three compounds (hits) from the virtual screening were subjected to quantum mechanical calculation using density functional theory. The Gaussian 09W program [19] was used for the calculations by optimizing the compounds' geometries at DFT/B3LYP/6-31G (d'p’) levels. The frontiers orbital energies, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO), energy gap, and the molecular electrostatic potential were computed in order to understand the electron acceptor and electron donor properties of the compounds. These also provide information about the chemical reactivity and stability of the compounds.

2.6. Molecular dynamics experimental design

In order to investigate the stability of the three selected ligands (MASA, 18-AGA, and Resveratrol), we designed our molecular dynamics simulation as follows:

Group A – Simple dynamics of Keap1 protein (Apoprotein Normal Control)

Group B – Complex dynamics of Keap1-MASA

Group C – Complex dynamics of Keap1-18-AGA

Group D – Complex dynamics of Keap1-Resveratrol

2.7. Molecular dynamics simulations

Before we ran the complex molecular dynamics simulation production for 20ns using GROMACS (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations) [20], we prepared files for the simple dynamics normal control group “4ZY3” and for the complexes which include 4ZY3-Resveratrol, 4ZY3-18-AGA, and 4ZY3-MASA. We used CHARMS-36 force field and TIP3P GROMACS recommended water model for the protein topology. CGENFF web server tool was used to prepare the “.str” file for the ligand topology after which the topology files of the complexes were appropriately updated using appropriate python codes to manually include ligands topology. We ionized and neutralized the systems and then solvated them using the simple point charge-216 explicit water model (spc216. gro). Energy minimization was run for 100ps (picoseconds) using steepest descent algorithm to establish a stable conformation for the system after which we equilibrated the system using Verlet algorithm from 0-310K at 100ps, 2fs (femtoseconds) time step for NVT, while Berenson algorithm at 2fs time step for 100ps was used for NPT equilibration. The system was treated using the “trjconv” module to centralize and compact the protein while we also made sure the atoms does not jump out of the PBC (Periodic Boundary Condition). RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) was calculated and reported as mean ± SD using the 2004frames for each 20ns production step run for each complex using “gmx analyze” GROMACS module after which the H-bonds were also calculated using “xmgrace” module.

3. Result

3.1. Validation of docking protocol

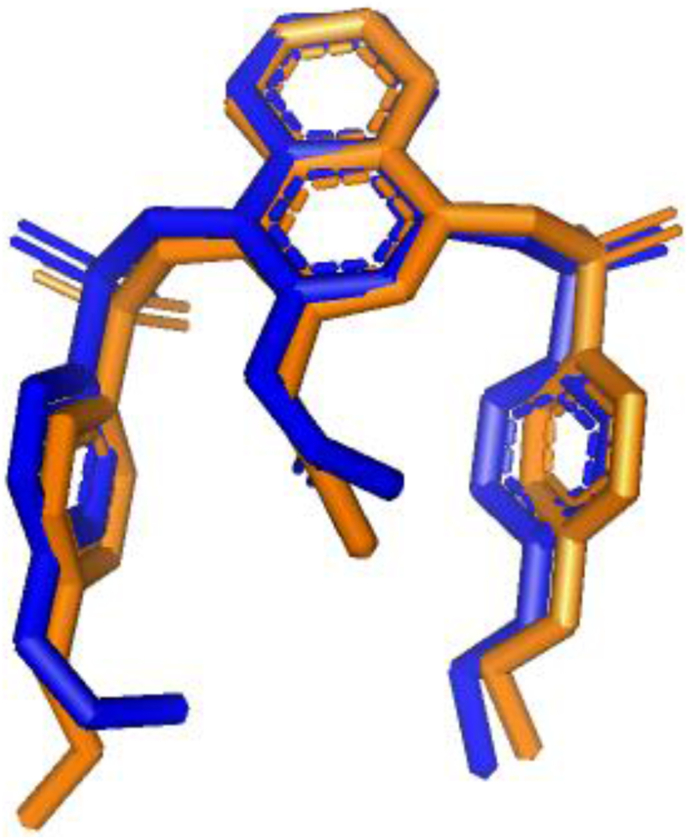

The extracted native ligand; K67 was re-docked within the kelch domain of the protein to validate the docking calculations, reliability, and reproducibility of the docking parameters for the study. The docked conformation of the extracted ligand is almost superimposed with the native co-crystallized ligand (Figure 2), which means the subsequent pose that this protocol generated are reliable. Interestingly, the best-docked pose showed the lowest binding affinity with -9.3 kcal/mol and the RMSD value of 0.00Å.

Figure 2.

The validation of docking performance by AutoDock Vina. The co-crystalized and docked (inhibitor K67) ligands are shown as sticks in blue and orange color, respectively.

3.2. Virtual screening analysis

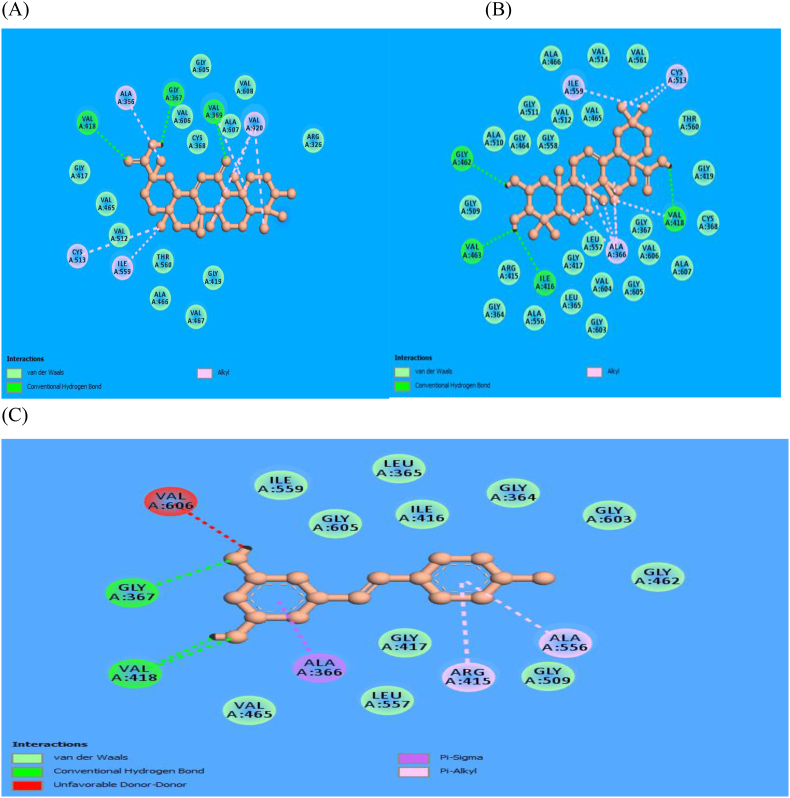

Molecular docking is a well-known computer-based method used in drug discovery which enables identification of new compounds of therapeutic essence by predicting ligand-target interactions and the affinity of the ligand to the target on a molecular platform [21]. Figure 1 shows the structure of Kelch-like ECH Associated Protein-1 (KEAP-1) with PDB ID:4ZY3 that was used as the target protein for this research. Fifty (50) antioxidant compounds were docked to Keap1 target protein 4ZY3 and the binding affinities of the selected compounds are reported in Table 1. Maslinic acid (MASA) had -10.6 kJ/mol, 18-alpha glycyrrhetinic acid (18-AGA) was -10.4JK/mol while resveratrol had -7.8 kJ/mol binding energy values. This shows that both MASA and 18-AGA have higher binding affinity than resveratrol. For 4ZY3-MASA, the amino acid residues participating in the hydrogen bonding formation include Ile416, Val418, Val462 and Val463, while that of 4ZY3-18-AGA includes Arg326, Gly367, Val369 and Val418 and that of 4ZY3-resveratrol are Gly367 and Val418. Hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions are also reported to participate and for 4ZY3-MASA, the hydrophobic interactions include Ala366, Val418, Cys513 and Ile559, while for 4ZY3-18-AGA we have Ala366, Val369, Val420, Cys513, and Ile559 and for 4ZY3-resveratrol, the hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions include Ala366, Ala556 and Arg415. The molecular interaction is displayed in Figure 3 below.

Table 1.

Binding affinity and molecular interaction of selected ligands with KEAP-1 (PDBID: 4ZY3).

| Ligands | Binding Affinity (ΔG), kcal/mol |

Aminoacids of keap-1 receptor forming h-bond with ligand | Electrostatic/Hydrophobic Interactions involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maslinic acid | -10.6 | Ile416, Val418, Val462, Val463 | Ala366, Val418, Cys513, Ile559 |

| 18-Alpha glycyrrhetinic acid | -10.4 | Arg326, Gly367, Val369, Val418 | Ala366, Val369, Val420, Cys513, Ile559 |

| Resveratrol | -7.8 | Gly367, 2(Val418) | Ala366, Ala556, Arg415 |

Figure 3.

Molecular interactions of 18-Alpha Glycyrrhetinic Acid, Maslinic Acid, and Resveratrol as shown in (A), (B), (C).

For bioavailability modeling, a way of figuring out compounds with a good absorption propensity is by screening the compounds with the Lipinski Rule of Five (RO5). The rule states that good absorption or permeation of a drug is more feasible if the chemical structure of the drug does not violate more than one of the following criteria/rules: (1) Molecular weight is less or equal to 500, (2) LogP should be less or equal to 5, (3) Hydrogen bond donor should be less or equal to 5, (4) Hydrogen bond acceptor should not be more than 10 [22]. Interestingly, from Table 2, some of the selected compounds; MASA and 18-AGA violated only one of the rules (MASA: LogP = 5.81, 18-AGA: LogP = 5.62) while Resveratrol violated none of the RO5. This signifies that MASA, 18-AGA and resveratrol could be druggable.

Table 2.

Drug-likeness Evaluation of the selected compounds using Molinspiration web tool.

| Ligand | Molecular Weight | miLogP | nHBA | nHBD | nViolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maslinic acid | 472.71 | 5.81 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 18-Alpha glycyrrhetinic acid | 470.69 | 5.62 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Resveratrol | 228.25 | 2.99 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

Assessment of ADMET (Adsorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) is an integral aspect of the early stage of drug discovery process for accelerating the conversion of hits and lead compounds into certified candidates for drug development. Drugs efficacies against therapeutic targets coupled with excellent ADMET profiling at a therapeutic dosage underscores a high-quality drug candidate [23, 24]. Table 3 shows the ADMET profile of the three selected antioxidant compounds computed using ADMETSAR2 web tool [18]. Interestingly, selected compounds showed promising likelihood of been absorbed in the human intestine (HIA+). The three selected compounds do not cross the BBB. Also, they express outstanding aqueous solubility (LogS). The cytochrome P450 parameters of the compounds reflect promising property. These enzymes speed-up the rate of various metabolic activities of therapeutic drugs. Just as expected, MASA, 18-AGA and resveratrol are non-inhibitors of all analyzed CyP450 inhibitors therefore, establishing their propensity to emerge as potential therapeutic drug candidates. The selected compounds are non-carcinogenic and non-biodegradable. Besides, AMES toxicity of the selected compounds was examined and seen to be non-AMES toxic. The slight toxicity of MASA, 18-AGA, and resveratrol was expressed with their type III oral acute toxicity but, the propensity to modify them to non-toxic type IV during lead optimization stage of drug development/discovery may still be feasible [25]. The interaction of good drug candidates with hERG (human ether a-go-go) is a critical parameter/biomarker considered in selecting good drug candidates and a good one should be a non-inhibitor of hERG because its inhibition may inhibit the potassium channels of heart muscles (myocardium) and could cause chronic heart challenges that might lead to death.

Table 3.

ADMET prediction of selected compounds.

| Absorption & distribution | C-1 | C-2 | S-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBB (+/-) |

0.3145 (BBB-) |

0.8514 (BBB-) |

0.6616 (BBB-) |

| HIA + | 0.9643 (96.43%) | 0.9901 (99.01%) | 0.9825 (98.25%) |

| Aqueous Solubility (LogS) |

-4.446 |

-4.065 |

-2.778 |

|

Metabolism | |||

| CYP450 2C19 inhibitor | 0.8826 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9604 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.8052 (Inhibitor) |

| CYP450 1A2 inhibitor | 0.8863 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9296 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9106 (Inhibitor) |

| CYP450 3A4 inhibitor | 0.8734 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.8309 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.7539 (Inhibitor) |

| CYP450 2C9 Inhibitor | 0.8938 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9317 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.7068 (Inhibitor) |

| CYP450 2D6 inhibitor |

0.9476 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9538 (Non-Inhibitor) |

0.9226 (Non-Inhibitor) |

|

Excretion | |||

|

Biodegradation |

0.8500 (Not Biodegradable) |

0.8500 (Not Biodegradable) |

0.8750 (Not Biodegradable) |

|

Toxicity | |||

| AMES toxicity | 0.9300 Not Ames toxic |

0.8500 Not Ames Toxic |

0.8200 Not Ames Toxic |

| Acute Oral Toxicity | 0.6470 III |

0.8402 III |

0.6825 III |

| Eye Irritation (YES/NO) |

0.9196 NO |

0.9397 NO |

0.9960 YES |

| Eye Corrosion (YES/NO) |

0.9937 NO |

0.9945 NO |

0.9561 NO |

| hERRG Inhibition | 0.6667 YES |

0.5310 YES |

0.8361 YES |

| Carcinogenicity | 1.0000 NO |

0.9731 NO |

0.5301 NO |

C-1 = maslinic acid, C-2 = 18-alpha-Glycyrrhetinic acid, S-1 = resveratrol.

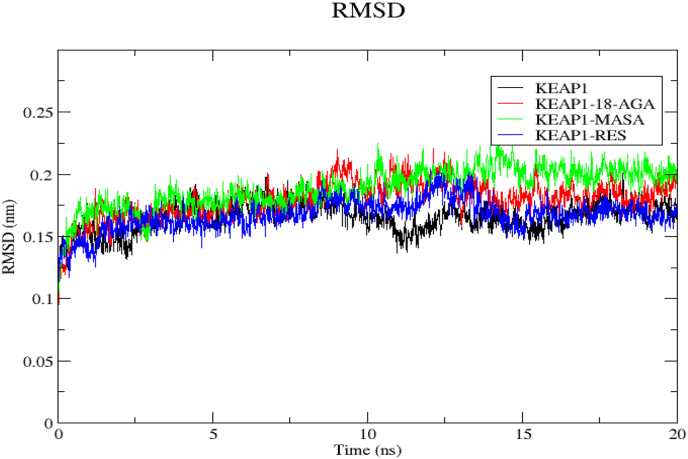

We used Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to estimate the structural drifts and alterations linked to the interactions between Keap1, MASA, 18-AGA and resveratrol using Keap1 as apoprotein and the result is presented as Figure 4 above. The RMSD values which are (KEAP1: 0.165 ± 0.013), (KEAP1-MASA: 0.189 ± 0.017), (KEAP1-18-AGA 0.179 ± 0.016) and (KEAP1)0.167 ± 0.013 for apoprotein, Keap1-MASA, Keap1-18-AGA and Keap1-RED respectively show that the 20ns trajectories captured no significant structural differences in the conformations of the complexes and when we compared the apoprotein KEAP1 with other complexes, we noticed a strict similarities in structural conformation which might infer that the ligands does not deviate from the initial kelch binding pocket.

Figure 4.

Represents the RMSD values of the protein-ligands complexes to the protein backbone for 20ns. RMSD of 4ZY3, 4ZY3-18-AGA, 4ZY3-MASA and 4ZY3-RES are shown in black, red, green and blue respectively.

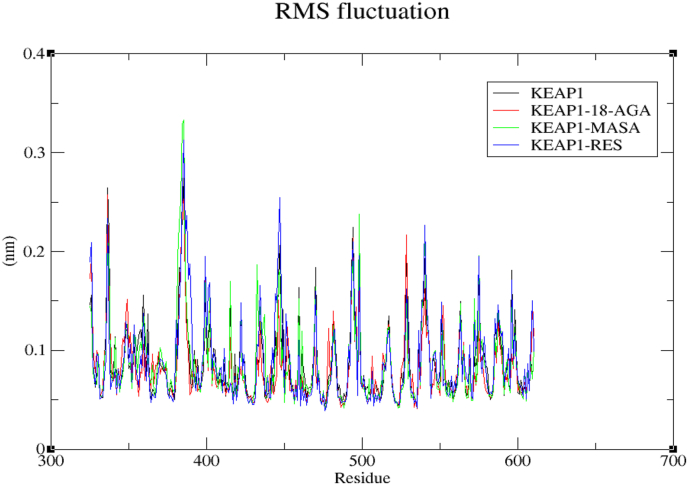

Besides, the local changes in the protein chain residues that was analyzed with Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of the changes in ligand atom positions at specific temperature and pressure. Fluctuations in the amino acid residues of Keap1 and all the complexes (Keap1-18-AGA, Keap1-MASA and Keap1-RES) were calculated from the 20ns trajectory files. We then compare and plotted the flexibility of each residue in the protein and the complexes as shown in Figure 5 above. For Keap1 apoprotein, KEAP1-MASA, KEAP1-18-AGA and KEAP1-RES, the RMSF values are 1.65nm, 0.98nm, 1.0nm and 0.99nm respectively. By comparing the RMSF of Keap1 apoprotein with the complexes, we could reveal the brain behind the dynamics of the individual residues of the protein backbone in such a way that wherever there are peaks, there could be some degree of flexibility and every loop region represent some magnitude of flexibility that depicts fluctuations while other regions with fewer fluctuations are the constrained residues where the ligand bound.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of RMSF value of the complex.

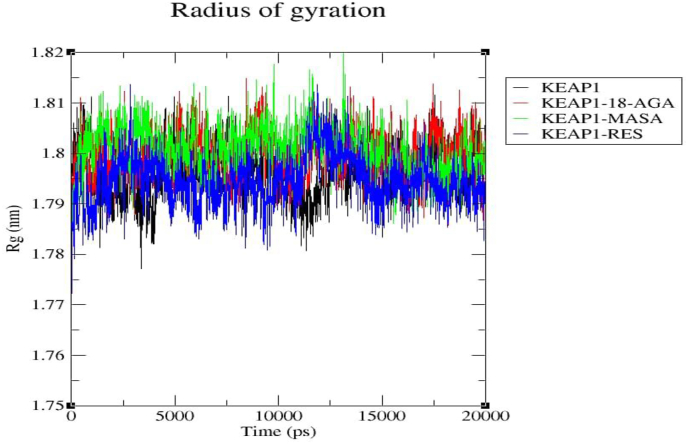

Radius of gyration (Rg) is used for the evaluation of the stability of complex biological systems by calculating the structural compactness of the biomolecules along the molecular dynamics trajectory [26]. We also used this parameter to confirm if the complexes were stably folded throughout the 20ns MD simulation and if the Rg are relatively consistent throughout the simulation, it is regarded as been stably folded [27]. The graph represented as Figure 6 is a function of Rg with respect to the time of simulations for both the Keap1 protein and the complexes (Keap1-MASA, Keap1-18-AGA and Keap1-RES). For Keap1 apoprotein control, Rg was 1.797nm ± 0.0053 (Black) while Keap1-18-AGA (Red), Keap1-MASA (Green) and Keap1-RES were1.800nm ± 0.0048, 1.801nm ± 0.0049 and 1.795nm ± 0.0052 respectively.

Figure 6.

Represents the ROG values of the protein-ligand complexes to the protein backbone for 20ns. ROG of KEAP1, KEAP1-MASA, KEAP1-18-AGA and KEAP1-RES are shown in black, red, and green respectively.

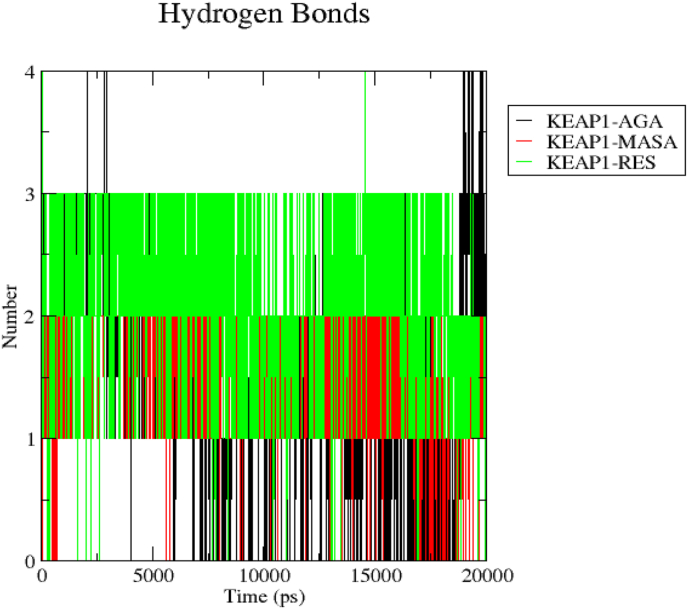

In this research, the hydrogen bonding interaction was calculated after the completion of the 20ns molecular dynamics simulation and the trajectories were exploited to estimate the consistency of the h-bond throughout the simulation. Right here, our aim is to detect the complex with the highest most stable hydrogen bond interactions which is a parameter to speculate how the stability was maintained throughout the 20ns generated trajectories. The h-bond analysis for KEAP1-MASA (Figure 7) is 1.59 ± 0.56 while that of KEAP1-18-AGA is 1.52 ± 0.92 and KEAP1-RES is 2.11 ± 0.72. This implies that RES has the highest average number of h-bond maintaining its stability throughout the 20ns simulation.

Figure 7.

Represents the number of hydrogen bonds responsible for the stability of the complexes (Keap1-MASA, Keap1-18-AGA and Keap1-RES) throughout the 20ns.

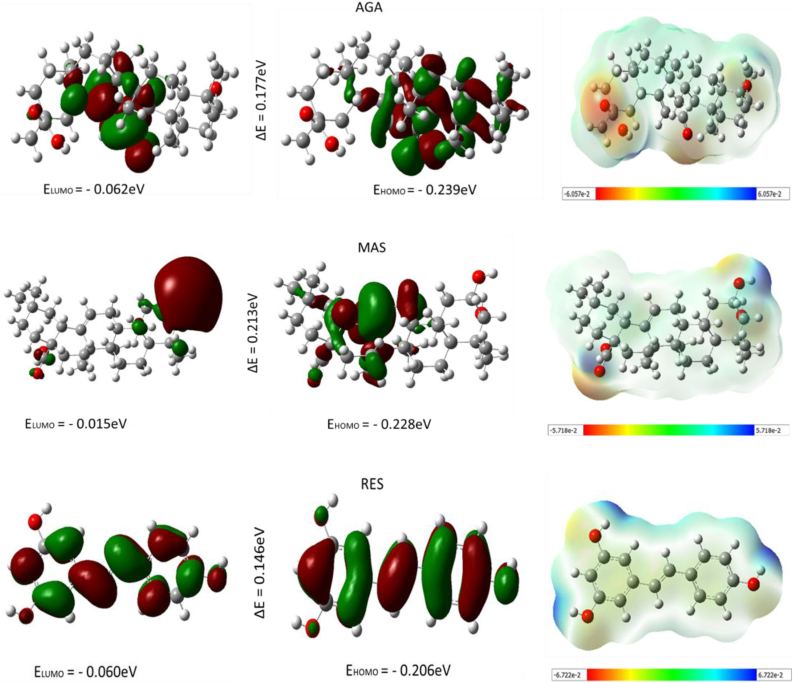

3.3. Density functional theory

The frontier orbitals, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) describe chemical species reactivity. The HOMO and LUMO describe the electron-donating and accepting ability of the compounds. Another parameter is the energy gap, which is the difference between the LUMO and the HOMO energy, representing the intramolecular charge transfer and kinetic stability. Compounds with a large energy gap are associated with low chemical reactivity and high kinetic stability. In contrast, those with a small energy gap are more reactive with less kinetic stability [28].

In this study, HOMO and LUMO energy was executed for the three top hit compounds (MASA, RES and 18-AGA) using the quantum mechanical Density Functional Theory (DFT) methodology and the result is presented in Figure 8. Resveratrol (Res) has the lowest energy gap of 0.146eV with -0.206eV and 0.060eV as HOMO and LUMO respectively. The 18-AGA has an energy gap of 0.177eV with -0.237eV and -0.062eV as HOMO and LUMO energy. In comparison, the MASA has an energy gap of 0.213eV with -0.228eV and -0.014eV as HOMO and LUMO energies (Table 4).

Figure 8.

Shows the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) respectively for each of the compounds.

Table 4.

Shows the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the energy gap.

| Compounds | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | Energy Gap(ΔE) (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGA | -0.239 | -0.062 | 0.177 |

| RES | -0.206 | -0.060 | 0.146 |

| MAS | -0.228 | -0.014 | 0.213 |

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) of the top hit compound was also plotted over the compounds' electronic structure from the DFT calculation. The observed MEP surface around a compound by the charge distribution provides information about the reactive sites for the nucleophilic and electrophilic attack in hydrogen bonding interactions [29] and other processes requiring biological recognition [30]. The MEP for the top hit compounds shows the electrophilic region and the nucleophilic region. The regions colored red in the MEP surface are the electrophilic region, the blue-colored regions are the nucleophilic regions, and the blue-green region is the less nucleophilic region. Most electrophilic attacks occurred on the Oxygen atoms and Nitrogen atoms in the compounds. In contrast, the blue-green region containing hydrogen atoms and methyl group forming the ring system of the compounds are the less nucleophilic region.

4. Discussion

The regulation of signaling pathways associated with various pathologies through the targeting of their key protein components could serve as molecular therapeutic targets for the management/treatment of various diseases [31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. In light of this, we used reported antioxidant compounds to target Nrf2 repressor (Keap1) using in silico methodologies in order to figure out the compounds with the best inhibitory potential against Keap1. The covalent interaction between the two kelch fingers of Keap1 represses Nr2 transcription factor within the cytoplasm thereby, channeling it for ubiquitin tagging that prepares it for 26S proteasomal degradation [31]. This mechanism inhibits Nrf2 nuclear translocation, thereby preventing the binding to the promoter region of its downstream genes and subsequent synthesis of antioxidant, cytoprotective, and detoxifying genes which could protect the cells from oxidative insults [31, 36, 37]. So, pure compounds/drugs/nutraceuticals that could either directly or indirectly therapeutically target Keap1 could promote Nrf2 nuclear translocation and also trigger its transcriptional proceedings to upregulate the antioxidant, cytoprotective and detoxifying genes meant for cells biosafety [31, 32, 38]. In this study, we identified some compounds that could serve as potent Nrf2 activator through the inhibition of its Keap1 repressor.

The better Keap1 binding affinity and hydrogen bonding of 4ZY3-MASA, 4ZY3-18-AGA and 4ZY3-resveratrol underscore their strong Keap1 inhibitory potential and antioxidant prowess. The binding affinity of other test compounds are reported in Table 5. This attribute could imply that these compounds might have the character to compete with Nrf2 at its Keap1 kelch domain binding site thereby, promoting availability for nuclear translocation and its subsequent transcriptional processes. Generally, hydrogen bonds are referred to as protein-ligand binding enhancers [39]. It may therefore mean that the strong hydrogen bonds might have contributed to their high binding affinities. In addition, we realized that Val418 is common to the three complexes and this could mean a conserved amino acid residue. We also think it could be the critical residue contributing immensely to the high binding energies reported for the complexes. Furthermore, the electrostatic/hydrophobic interactions reported to occur between the complexes with 4ZY3-MASA (4), 4ZY3-18-AGA (5) and 4ZY3-resveratrol (3) is another rationale that elucidates the brain behind their higher binding affinities. Ala366 was found common to all the three complexes and this may infer that this residue could be critical to their high binding affinity and could be a conserved residue just as reported for Val418. It is noteworthy that this same Val418 had been reported as one of the residues that forms hydrogen bond interaction with keap1 binding sites when desoxyrhapontigenin was docked with keap1 and was further concluded to have contributed to the Nrf2 activation through the inhibition of keap1 repressing activity [40]. Another finding that falls in perspective with ours reported that compounds from Pergulariadeaemia and Terminalia catappa leaf extracts including genistein and apigenin 6C glycoside interact with Keap1 kelch domain (Nrf2 binding site) through the formation of hydrogen bond with Val418 residue [41]. Ala366 was also the paramount hydrophobic/electrostatic interaction for the three complexes and it may infer that this residue is important for the strong binding energies reported. An in silico aspect of a research that provided evidence that phloretin could ameliorate high-glucose-induced cardiomyocyte oxidation and fibrosis by targeting Keap1/Nrf2 signaling reported the details of the interactions between phloretin and keap1 using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations and gibbs free energy decomposition method. They found that Ala366 was among the ten (10) residues that contributed to the strong binding energies of Keap1-phloretin complex [42]. This might validate the importance of Ala366 to Keap1 activity. Due to the examined Keap1/Nrf2 signaling modulating potential of BNUA-3 in hepatocarcinogenesis, its keap1 inhibition prowess was investigated using molecular docking simulation study in order to buttress these findings. It was observed that Ala366 was one of the residues that formed hydrophobic interactions with the phenyl ring at the second position of quinazoline at Keap1 active site. This finding might further emphasize the importance of Ala366 towards Keap1 bioactivity [43].

Table 5.

Compounds investigated during Virtual screening and their respective energy value using Autodock Vina.

| Compounds | Binding energy value |

|---|---|

| 4-o-cafffeoylquinic acid | -9.4 |

| Allyl Isothiocyanate | -3.2 |

| alpha tocotrienol | -9.1 |

| Andalusol | -7.3 |

| Andrographolide | -8.8 |

| Ankaflavin | -7 |

| Antroquinonol | -7.7 |

| Apigenin | -9.1 |

| Benzyl Isothiocyanate | -5 |

| Bergenin | -8 |

| Beta Mercapto Ethanol | -2.7 |

| butein | -8.4 |

| Carnosic acid | -9 |

| Catalposide | -9.5 |

| catechol | -5.1 |

| Celastrol | -11.4 |

| 18alpha-Glycyrrhetinic acid | -10.4 |

| Conchitriol | -9.2 |

| curcumin | -8.3 |

| Cyanidin-3-Glucoside | -6.2 |

| Cymopol | -7.3 |

| delta tocotrienol | -8.2 |

| Diallyl disulfide | -3.4 |

| eckol | -9.3 |

| Emodin | -9.8 |

| Forsythiaside A | -10.9 |

| Fucoxanthin | -10.4 |

| gamma tocotrienol | -8.3 |

| isoliquiritigenin | -8.1 |

| Lagascatriol | -9.3 |

| licochalcone A | -8 |

| pterostilbene | -7.5 |

| Melatonin | -6.7 |

| Mollugin | -7.4 |

| Naringenin | -9.3 |

| Parthenolide | -7.5 |

| Phenethyl isothiocyanate | -4.9 |

| resverastrol | -7.8 |

| rutin | -9.8 |

| S-Allyl-L-cysteine | -4.7 |

| Salvianolic Acid | -9.6 |

| Schisandrin B | -8.3 |

| Scopoletin | -6.9 |

| Verproside | -10.6 |

| withaferin | -10.6 |

| Zerumbone | -7.1 |

| cathechin | -9.3 |

| Galic acid | -9.6 |

| Gentisic acid | -6.3 |

| Maslinic acid | -10.5 |

The stability of MASA, 18-AGA and resveratrol at Keap1 kelch domain was investigated using molecular complex dynamics simulation for 20ns in order to explain the atomistic mechanism surrounding these interactions as this will unravel their pharmaceutical relevance in terms of therapeutic efficacy. We therefore use this method to study protein-ligand interactions in order to establish the stability of 18-AGA, MASA and resveratrol at the active pocket of Keap1 using RMSD, h-bond, ROG and RMSF parameters. Results showed that these three compounds are all stable at the kelch domain of Keap1however; it also accentuates resveratrolas the best of the three compounds. In addition, it indicates that there are no significant structural changes/alterations between the complex throughout the simulations and they have similar interactions with solution with respect to the apoprotein Keap1. In order words, it infers that there is no drifting from the initial position of the complexes. Furthermore, we investigated the h-bond interactions and their contribution towards the stability of each of the complexes in other to elucidate the rationale surrounding the stability of the complexes and we found that Keap1-RES complex had the highest average h-bonds (2.11 ± 0.72) participating in the complex stability almost throughout the 20ns while out of the four (4) h-bonds for Keap1-MASA complex, only 1.59 ± 0.56 participated in the interaction throughout the 20ns. For Keap1-18-AGA complex, out of its four (4) h-bonds, an average of1.52 ± 0.92 actively maintained its stability. This might be the brain behind the stability of these complexes. However, it could be that the participation of the 3 hydrogen bonds formed by Gly367 and Val418 with resveratrol for the 20ns accounted for its best RMSD value of 1.67Å(stability) because these residues were able to maintain the interaction between the ligand and Keap1 almost throughout the 20000ps. It was also reported that the reasons behind the instability of ligands to the binding sites of protein could be mediated by different binding modes. The higher the number of binding modes, the more unstable the complexes. So, it could be that resveratrol had lesser binding modes when compared to MASA and 18-AGA. In a report where multiple binding modes for Keap1-Nrf2 was investigated using MD, it was elucidated that bound ligands tend to dissociate after 20ns simulations while the stability of this complex systems were upheld by many h-bonds estimations. It was also noted that the complex with the higher h-bond reflected a higher stability [44]. The quantum mechanical based density functional theory that was used to expatiate the binding interaction between the selected compounds and their Keap1 target was used to elucidate their potential drug-target interactions. The HOMO and LUMO calculations with the energy gap point at RES as the best candidate when compared to others due to its stability.

5. Conclusion

In a nutshell, out of all the fifty (50) reported antioxidant compounds explored in this research, application of molecular docking simulation, ADMET profiling and Lipinski Rule of 5 (RO5) revealed MASA, 18-AGA, and RES as the best Keap1-kelch inhibitors due to their good pharmacokinetic properties coupled with strong Keap1 binding affinity. Also, molecular dynamics simulation and density functional theory calculations underscored RES as the best Keap1-kelch inhibitor due to its stability and compactness at the Keap1 kelch pocket. We hereby suggest that these compounds might hold the strength to activate Nrf2 due to their Keap1 inhibitory potential. Interestingly, our results point at RES as the best Keap1 inhibitor. So, further in vitro and in vivo investigations are required for validation beforehand concluding if these three compounds are good candidates.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Temitope Isaac Adelusi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Misbaudeen Abdul-Hammed: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mukhtar Oluwaseun Idris: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Qudus Kehinde Oyedele: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Ibrahim Olaide Adedotun: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ibrahim Damilare Boyenle, Ukachi Chiamaka Divine, Ogunlana Abdeen Tunde and other students at the computational Biology/Drug discovery laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomosho, Nigeria, for making this research work a success.

References

- 1.De Bont R., van Larebeke N. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: a review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis. 2004 May;19(3):169–185. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Talalay P. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of inducers of cytoprotective proteins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008 Jun;52(Suppl 1):S128–S138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700195. PMID: 18327872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y., Paonessa J.D., Zhang Y. Mechanism of chemical activation of Nrf2. PloS One. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035122. Epub 2012 Apr 25. PMID: 22558124; PMCID: PMC3338841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu M.C., Ji J.A., Jiang Z.Y., You Q.D. The keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target: an update. Med. Res. Rev. 2016 Sep;36(5):924–963. doi: 10.1002/med.21396. 2016 May 18. PMID: 27192495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keleku-Lukwete N., Suzuki M., Yamamoto M. An overview of the advantages of KEAP1-NRF2 system Activation during inflammatory disease treatment. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;29(17):1746–1755. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock R., Schaap M., Pfister H., Wells G. Peptide inhibitors of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction with improved binding and cellular activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013 Jun 7;11(21):3553–3557. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40249e. Epub 2013 Apr 24. PMID: 23615671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahremany S., Babaev I., Hasin P., Tamir T.Y., Ben-Zur T., Cohen G., Jiang Z., Weintraub S., Offen D., Rahimipour S., Major M.B., Senderowitz H., Gruzman A. Computer-aided design and synthesis of 1-{4-[(3,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)amino]phenyl}-5-oxopyrrolidine-3-carboxylic acid as an Nrf2 enhancer. Chempluschem. 2018 May;83(5):320–333. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201700539. Epub 2018 Mar 8. PMID: 31957349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tkachev V.O., Menshchikova E.B., Zenkov N.K. Mechanism of the Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling system. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2011 Apr;76(4):407–422. doi: 10.1134/s0006297911040031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canning P., Sorrell F.J., Bullock A.N. Structural basis of Keap1 interactions with Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015 Nov;88(Pt B):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.034. Epub 2015 Jun 7. PMID: 26057936; PMCID: PMC4668279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kansanen E., Kuosmanen S.M., Leinonen H., Levonen A.L. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway: mechanisms of activation and dysregulation in cancer. Redox. Biol. 2013 Jan 18;1(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.10.001. PMID: 24024136; PMCID: PMC3757665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baird L., Dinkova-Kostova A.T. The cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2011 Apr;85(4):241–272. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0674-5. Epub 2011 Mar 2. PMID: 21365312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Londhe A.M., Gadhe C.G., Lim S.M., Pae A.N. Investigation of molecular details of keap1-Nrf2 inhibitors using molecular dynamics and umbrella sampling techniques. Molecules. 2019 Nov 12;24(22):4085. doi: 10.3390/molecules24224085. PMID: 31726716; PMCID: PMC6891428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora R., Sawney S., Saini V., Steffi C., Tiwari M., Saluja D. Esculetin induces antiproliferative and apoptotic response in pancreatic cancer cells by directly binding to KEAP1. Mol. Cancer. 2016 Oct 18;15(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0550-2. PMID: 27756327; PMCID: PMC5069780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T., Ichimura Y., Taguchi K., Suzuki T., Mizushima T., Takagi K., Hirose Y., Nagahashi M., Iso T., Fukutomi T., Ohishi M., Endo K., Uemura T., Nishito Y., Okuda S., Obata M., Kouno T., Imamura R., Tada Y., Obata R., Yasuda D., Takahashi K., Fujimura T., Pi J., Lee M.S., Ueno T., Ohe T., Mashino T., Wakai T., Kojima H., Okabe T., Nagano T., Motohashi H., Waguri S., Soga T., Yamamoto M., Tanaka K., Komatsu M. p62/Sqstm1 promotes malignancy of HCV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma through Nrf2-dependent metabolic reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2016 Jun 27;7:12030. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12030. PMID: 27345495; PMCID: PMC4931237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009 Dec;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. PMID: 19399780; PMCID: PMC2760638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S., Thiessen P.A., Bolton E.E., Chen J., Fu G., Gindulyte A., Han L., He J., He S., Shoemaker B.A., Wang J., Yu B., Zhang J., Bryant S.H. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jan 4;44(D1):D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. Epub 2015 Sep 22. PMID: 26400175; PMCID: PMC4702940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010 Jan 30;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. PMID: 19499576; PMCID: PMC3041641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H., Lou C., Sun L., Li J., Cai Y., Wang Z., Li W., Liu G., Tang Y. admetSAR 2.0: web-service for prediction and optimization of chemical ADMET properties. Bioinformatics. 2019 Mar 15;35(6):1067–1069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J., Wang L., Xin Y., Song M. Polarization properties of superposed vector Laguerre-Guassian beams during propagation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. Opt Image Sci. Vis. 2017 Oct 1;34(10):1924–1933. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.34.001924. PMID: 29036064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A.E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005 Dec;26(16):1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. PMID: 16211538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinzi L., Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019 Sep 4;20(18):4331. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. PMID: 31487867; PMCID: PMC6769923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004 Dec;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. PMID: 24981612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Souza Neto L.R., Moreira-Filho J.T., Neves B.J., Maidana R.L.B.R., Guimarães A.C.R., Furnham N., Andrade C.H., Silva F.P., Jr. In silico strategies to support fragment-to-lead optimization in drug discovery. Front. Chem. 2020 Feb 18;8:93. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00093. PMID: 32133344; PMCID: PMC7040036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan L., Yang H., Cai Y., Sun L., Di P., Li W., Liu G., Tang Y. ADMET-score - a comprehensive scoring function for evaluation of chemical drug-likeness. Medchemcomm. 2018 Nov 30;10(1):148–157. doi: 10.1039/c8md00472b. PMID: 30774861; PMCID: PMC6350845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onawole A.T., Sulaiman K.O., Adegoke R.O., Kolapo T.U. Identification of potential inhibitors against the Zika virus using consensus scoring. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2017 May;73:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.01.018. Epub 2017 Feb 9. PMID: 28236744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahbaaz M., Nkaule A., Christoffels A. Designing novel possible kinase inhibitor derivatives as therapeutics against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an in silico study. Sci. Rep. 2019 Mar 13;9(1):4405. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40621-7. PMID: 30867456; PMCID: PMC6416319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghasemi F., Zomorodipour A., Karkhane A.A., Khorramizadeh M.R. In silico designing of hyper-glycosylated analogs for the human coagulation factor IX. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2016 Jul;68:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2016.05.011. Epub 2016 Jun 7. PMID: 27356208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heßelmann A. DFT-SAPT intermolecular interaction energies employing exact-exchange Kohn-Sham response methods. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2018 Apr 10;14(4):1943–1959. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b01233. Epub 2018 Apr 2. PMID: 29566325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rathi P.C., Ludlow R.F., Verdonk M.L. Practical high-quality electrostatic potential surfaces for drug discovery using a graph-convolutional deep neural Network. J. Med. Chem. 2020 Aug 27;63(16):8778–8790. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01129. Epub 2019 Sep 25. PMID: 31553186. s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bitencourt-Ferreira G., de Azevedo Junior W.F. Electrostatic potential energy in protein-drug complexes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021 Feb 1 doi: 10.2174/0929867328666210201150842. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33593246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.[a] Niture S.K., Khatri R., Jaiswal A.K. Regulation of Nrf2-an update. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014 Jan;66:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.008. Epub 2013 Feb 19. PMID: 23434765; PMCID: PMC3773280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; [b] Adelusi T.I., Du L., Hao M., Zhou X., Xuan Q., Apu C., Sun Y., Lu Q., Yin X. Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling unfolds therapeutic targets for redox imbalanced-mediated diseases and diabetic nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020 Mar;123:109732. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109732. Epub 2020 Jan 13. PMID: 31945695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyenle I.D., Divine U.C., Adeyemi R., Ayinde K.S., Olaoba O.T., Apu C., Du L., Lu Q., Yin X., Adelusi T.I. Direct Keap1-kelch inhibitors as potential drug candidates for oxidative stress-orchestrated diseases: a Review on Insilico perspective. Pharmacol. Res. 2021 Mar 24:105577. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105577. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33774182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaac A.T., Du L., Chowdhury A., Xiaoke G., Lu Q., Yin X. Signaling pathways and proteins targeted by antidiabetic chalcones. Life Sci. 2020 Dec 30:118982. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118982. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33387581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adelusi T.I., Akinbolaji G.R., Yin X., Ayinde K.S., Olaoba O.T. Neurotrophic, anti-neuroinflammatory, and redox balance mechanisms of chalcones. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021 Jan 15;891:173695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173695. Epub 2020 Oct 27. PMID: 33121951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayinde K.S., Olaoba O.T., Ibrahim B., Lei D., Lu Q., Yin X., Adelusi T.I. AMPK allostery: a therapeutic target for the management/treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Life Sci. 2020 Nov 15;261:118455. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118455. Epub 2020 Sep 18. PMID: 32956662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serafini M.M., Catanzaro M., Fagiani F., Simoni E., Caporaso R., Dacrema M., Romanoni I., Govoni S., Racchi M., Daglia M., Rosini M., Lanni C. Modulation of keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway by curcuma- and garlic-derived hybrids. Front. Pharmacol. 2020 Jan 28;10:1597. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01597. PMID: 32047434; PMCID: PMC6997134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S., Hu L. Nrf2 activation through the inhibition of Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction. Med. Chem. Res. 2020 May;29(5):846–867. doi: 10.1007/s00044-020-02539-y. Epub 2020 Apr 10. PMID: 32390710; PMCID: PMC7207041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mou Y., Wen S., Li Y.X., Gao X.X., Zhang X., Jiang Z.Y. Recent progress in Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020 Sep 15;202:112532. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112532. Epub 2020 Jul 6. PMID: 32668381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salentin S., Haupt V.J., Daminelli S., Schroeder M. Polypharmacology rescored: protein-ligand interaction profiles for remote binding site similarity assessment. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014 Nov-Dec;116(2-3):174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.05.006. Epub 2014 Jun 9. PMID: 24923864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joo Choi R., Cheng M.S., Shik Kim Y. Desoxyrhapontigenin up-regulates Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages and inflammatory lung injury. Redox. Biol. 2014 Feb 18;2:504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.02.001. PMID: 24624340; PMCID: PMC3949088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molecular docking studies of the compounds from Pergularia daemia and Terminalia catappa L. leaf extracts with CYP2E1,GST,UDP-Glucuronyl transferase and Nrf2 binding site in keap1. IJPSR. 2018;41:2037–2047. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ying Y., Jin J., Ye L., Sun P., Wang H., Wang X. Phloretin prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by dissociating keap1/Nrf2 complex and inhibiting oxidative stress. Front. Endocrinol. 2018 Dec 20;9:774. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00774. PMID: 30619098; PMCID: PMC6306411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bose P., Siddique M.U.M., Acharya R., Jayaprakash V., Sinha B.N., Lapenna A., Pattanayak S.P. Quinazolinone derivative BNUA-3 ameliorated [NDEA+2-AAF]-induced liver carcinogenesis in SD rats by modulating AhR-CYP1B1-Nrf2-Keap1 pathway. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020 Jan;47(1):143–157. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13184. Epub 2019 Oct 28. PMID: 31563143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satoh M., Saburi H., Tanaka T., Matsuura Y., Naitow H., Shimozono R., Yamamoto N., Inoue H., Nakamura N., Yoshizawa Y., Aoki T., Tanimura R., Kunishima N. Multiple binding modes of a small molecule to human Keap1 revealed by X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamics simulation. FEBS Open Bio. 2015 Jun 30;5:557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.06.011. PMID: 26199865; PMCID: PMC4506958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.