Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has become a crucial public health problem in the world that disrupted the lives of millions in many countries including the United States. In this study, we present a decision analytic approach which is an efficient tool to assess the effectiveness of early social distancing measures in communities with different population characteristics. First, we empirically estimate the reproduction numbers for two different states. Then, we develop an age-structured compartmental simulation model for the disease spread to demonstrate the variation in the observed outbreak. Finally, we analyze the computational results and show that early trigger social distancing strategies result in smaller death tolls; however, there are relatively larger second waves. Conversely, late trigger social distancing strategies result in higher initial death tolls but relatively smaller second waves. This study shows that decision analytic tools can help policy makers simulate different social distancing scenarios at the early stages of a global outbreak. Policy makers should expect multiple waves of cases as a result of the social distancing policies implemented when there are no vaccines available for mass immunization and appropriate antiviral treatments.

Keywords: COVID-19, Decision analysis, Compartmental model, Reproductive number estimation, Social distancing

1. Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global outbreak caused by Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic. This new virus is of the coronavirus family, named SARS-CoV-2 [7], which was first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and quickly spread around the world. Although there are still several unknowns regarding the natural characteristics of the virus, the main mode of transmission is identified to be mainly through respiratory droplets expelled from the mouth or nose of an infected person and subsequently inhaled by a susceptible person. It is possible to get COVID-19 through contact with contaminated surfaces [6]. In addition, early epidemiological estimates show that the severity of this novel virus is relatively higher in elderly populations than younger populations [28]. Fig. 1 shows the chronological evolution of the pandemic and related data in the US and the timeline when both states had to consider social distancing policies with controversial reopening decisions. We have considered the available data by the end of April 2020, in our global and local estimations for model parameters.

Fig. 1.

Timeline.

Global pandemics have been major threats not only to public health systems but also to social and economic lives of nations worldwide. Decision support tools have been invaluable tools to identify timely response strategies with emerging data and modeling approaches play a key role with other health information systems [16]. The COVID-19 pandemic has become a crucial public health issue in the world that disrupted the lives of millions in many countries including the United States. During the early stages of the pandemic, interventions are designed to increase social distancing between individuals to reduce the transmissibility and eventually dampen the burden on the healthcare system. The effectiveness of these social distancing measures depends on the population density and underlying mobility patterns. In the United States (US), the states show significant variation in population density and demographic configurations. For example, as some Midwestern states, e.g., Nebraska, have drastically different mobility and social dynamics than states with mega cities, e.g., New York and New York City. While Nebraska has low population density and mobility patterns with relatively less use of public transportation, in New York City, with higher population density, public transportation use is more common. Therefore, during the early stages of the pandemic local decision makers need to identify social distancing policies that reflect their local epidemic dynamics with the social needs and realities. Such a decision support system that integrates the local epidemic data and growth estimates to inform the policy decision analysis is invaluable for public health practitioners and policy makers.

In this article, we present a decision analytic approach which presents an efficient tool to assess the effectiveness of early social distancing measures in communities with different population characteristics. First, we empirically estimate the reproduction numbers for two different states using their early local number of cases data. Then, we present an age-structured compartmental simulation model for the disease spread in order to demonstrate the variation in the observed outbreak. Through computational experiments, we show that social distancing measures with different decision parameters and paths (e.g., various triggers to start and different lengths of social distancing) can result in effective management of the outbreak in dissimilar states. We show how early trigger and late trigger options play a role on the peak magnitude and timing, and the overall death toll of the outbreak. Finally, we analyze the computational results and show that early trigger social distancing strategies result in smaller death tolls, however relatively larger second waves. Conversely, late trigger social distancing strategies result in higher initial death tolls but relatively smaller second waves.

This study presents a decision analytic tool that is designed to integrate evolving epidemic data and growth with a simulation model which can help policy makers simulate different social distancing scenarios at the early stages of a global outbreak. Using the decision analysis structure, we analyze reopening strategies with a two-phased reopening scenario. Our results show that, for the outbreak with smaller transmission rate, a short length of social distancing and immediate reopening scenario may be effective for epidemic control. Whereas, for outbreaks with medium or high transmission rates, the longer the phases until the re-opening the more dampened the burden of the outbreak (i.e., reduced number of death individuals), and the further the timing of the peak. This may also provide more time for the public health officials to increase healthcare capacity.

2. Literature review

While the early epidemiological estimates about the natural progression of the disease were reported with significant uncertainty, the public health authorities and researchers around the globe reported their surveillance data and findings that provided details about case fatality rates and transmissibility. An early study on the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 analyzed data of the first 425 confirmed cases in Wuhan, China and found that the mean incubation period was 5.2 days. However, the 95th percentile of the incubation period was 12.5 days in this sample [19]. In addition, this study estimated the basic reproductive number (R 0), which is the average number of secondary cases generated from a single infectious case in a completely susceptible population, as anywhere between 1.5 and 3.5 [19]. These epidemiological estimates show that the virus strain is highly transmissible and can infect mass populations across the globe in a short amount of time. Another study on news reports and press releases about COVID-19 outside Wuhan estimated the mean incubation period and 97.5th percentile as 5.1 days and 11.5 days, respectively [17]. Linton et al. [21] also estimated the expected incubation time around 5 days with relatively higher range of 2 to 14 days. Given the relatively high estimates of the basic reproductive number R 0, and relatively long incubation period, there is an exponential growth of confirmed COVID-19 cases in several countries and developing a control measure for the epidemic is quite challenging. More importantly, a significant proportion of cases are reported to be asymptomatic but infectious cases [19]. This characteristic of the virus is found to be one of the main drivers of the spread of COVID-19 across populations. Therefore, social distancing measures are crucial to gain time for healthcare systems to meet the demand for care and ultimately mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

By mid-March, there had been a significant impact on the economy of several countries as more restrictions to mitigate the risk were implemented, such as travel bans, cancellation of social events (concerts, sports, etc.), closure of non-essential businesses, and “stay-at-home” orders. While social distancing interventions have been implemented in various states of the US, as well as other countries worldwide, they have been controversial since they can have significant impact on the economy. Because it is usually hard to accurately estimate the transmissibility and severity of infections caused by a newly emerged virus at the early stages of the epidemic, there will still be many uncertainties about disease progression dynamics in the communities. Therefore, the public health decision makers will have to make important decisions on using school closures and other social distancing measures as community mitigation strategies until the right strain of a vaccine is developed and distributed. However, these strategies may vary based on the social and demographic characteristics of different communities. In this article, we present the timely evolution of the estimates of the reproductive number in two different states, i.e., New York where we observe high transmission rates; and Nebraska where we observe relatively lower community transmission rates, along with a baseline scenario based on more global estimates. We evaluate social distancing measures to analyze whether one unified policy would be effective in completely different states in the US, in terms minimizing number of cases and fatalities.

Social distancing measures have a significant impact on the spread of infectious diseases in populations; this is also observed during the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. Recently, in the literature there are several analytical approaches developed to analyze effectiveness and/or cost effectiveness of various public health mitigation strategies. Fumanelli et al. [13] consider school closure-based social distancing interventions in which closure strategies are based on school absenteeism: nationwide, countywide, reactive school-by-school and reactive gradual. Gojovic et al. [14] developed a simulation model for the H1N1 2009 outbreak in a structured population in Ontario and evaluated different mitigation strategies. In their analysis the decision analytic framework is used for different mitigation strategies that include school closures; however, these analyses are limited and do not involve any cost effectiveness analysis. Ciavarella et al. [8] studied school closure policies at the municipality level for mitigating influenza spread using compartmental models. Decision analytics and support systems are used with compartmental model to control infectious disease epidemics.

While a pandemic possibility continuously posed global risks to public health systems and business continuity Araz et al. [4], federal and state health departments developed public health policies for mitigation and response [25]. While modeling and simulation studies are used for optimal pharmaceutical intervention design, which include vaccination policies Duijzer et al. [11,12], non-pharmaceutical interventions are also modeled with disease progression dynamics Griffiths et al. [15], Teytelman & Larson [27]. In the development of social distancing policies, researchers and public health officials have used models and quantitative analyses to evaluate their effectiveness and costs under possible pandemic scenarios. Several decision support systems and visualization tools were developed earlier to improve public health preparedness, which include the evaluation of school closures across states Araz et al. [3], as well as optimization for distribution of pharmaceutical resources Arora et al. [5]. Recently, the role of decision support tools with interactive dashboards are assessed for emergency response and situation awareness [24], which can also display simulation results for scenario analyses and public health response.

Regarding the epidemiological effectiveness of the social distancing measures, policy makers become interested in simulated effectiveness in mitigating pandemic. Therefore, here we focus on the potential social distancing policies. In the literature, some studies demonstrate school closures can have a significant impact on the effective reproduction number and on the overall spread of disease [18]. Public health expert advocates, for example, 26 weeks of school closure in conjunction with other policies [26]. Since the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009, many studies showed the cost effectiveness and epidemiological impact of a large set of school closure policies. Different from the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, the COVID-19 pandemic has raised more political, social, and economic challenges as it turned to be a more severe pandemic. Therefore, in this article we evaluate several more comprehensive social distancing policies coupled with different strategies to reopen. The outcome measures considered for the policies are health care utilization and fatalities via a model that is calibrated based on state specific transmission data and socio-demographic decomposition. This study contributes to the literature by presenting a data-driven epidemiological modeling with decision analytics framework to support social distancing policies for different states. In addition, the analysis shows that multiple waves of infections should be expected based on the social distancing policies, which would vary in peak magnitude and timing depending on the policies. Finally, the study highlights how the time gained by using social distancing interventions can vary across states with different population configurations until mass vaccination or antiviral dispensing can become available.

3. Designing a decision analytics tool

In this paper, we present a decision analytic approach for evaluating the social distancing policies during a pandemic to inform local decision-makers. After using the state prevalence data to estimate the local reproduction number, we develop an age-structured mass action compartmental model parametrized based on this estimation. Then we integrated a decision analytical framework that reflects the potential policy options for social distancing to evaluate the impact of public health interventions for closure and reopening. The impact of these strategies is evaluated based on the computational results obtained for cumulative attack rate, projected peak prevalence (%), timing of the peak, peak hospitalizations, and cumulative deaths. This designed decision support framework is presented in Fig. 2 . Next, we explain social distancing policies considered, the data used, the disease spread simulation model, and the modeling mechanism for the closure and reopening decisions.

Fig. 2.

Decision Support Framework for COVID-19 Social Distancing Policy Evaluation.

3.1. Social distancing policy options

In our decision analytic approach, we consider three main social distancing strategies coupled with reopening decisions: first one is No closure strategy, i.e., when no social distancing measure is implemented which is also the base case; second is the social distancing with Immediate Reopening strategy, which is when social distancing measures are implemented for a fixed duration and followed by a complete reopening; and the third one is Reopening with Phases strategy, i.e., when social distancing measures are implemented and followed by a two-phased reopening. These policy options are modeled by adjusting contact rates for considered age groups. In No Closure strategy, contact rates are kept unchanged. In Immediate Reopening strategy, contact rates are reduced during a fixed length closure duration. After this duration, contact rates are set back to their original values. In Reopening with Phases, contact rates are first reduced during a fixed length of closure duration, then in phase 1 they are slightly increased from their values during closure. In phase 2, contact rates are further increased. Finally, after phase 2, contact rates are set back to their original values. Since, at the time of this research, not enough data were available for social distancing compliance, in specific communities, we are not considering the compliance as a modeling factor.

The social distancing measures are triggered with the prevalence in the community similar to Araz et al. [2], as most of the social distancing policies are implemented by monitoring the % of cases as triggers. The values of closure duration considered in our analysis are 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16 and 24 weeks, which are coupled with the prevalence based triggers, i.e., 0.001%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, 0.4%, 0.5% and 1%. See Fig. 3 for all the scenarios considered in our analyses. In the next section we explain the data used in this study.

Fig. 3.

Social distancing triggers and duration options.

3.2. Data

The early published estimates of the basic reproduction number (R 0) of the COVID-19 were slightly higher than 2 [19]. However, depending on the source of the data used in these estimation studies, there were some variations in these estimates. In addition to the basic reproductive number, other estimates of the key parameters used in the model are presented in Table 1 which are compiled from the literature and include the latency period, the proportion of the asymptomatically infected individuals, age dependent hospitalization, and mortality rates.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

| Definition of Parameters | Notation | Value | Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force of infection | computed | – | – | – |

| Basic reproductive number | R0 | 2.1 | [1.5,3.15] | – |

| Transmission between age groups | βij | Supp. Table 1 | − | – |

| Age specific contact rates | cij | Supp. Table 2 | − | Mossong et al. [23] |

| Asymptomatic latency period | ξ1 | 5 days | − | Li et al. [20] |

| Symptomatic latency period | ξ2 | 5 days | − | Li et al. [20] |

| Asymptomatic proportion | α | Uniformly distributed | 10 − 34.8% | [6,7] Mizumoto et al. [22] |

| Rate of asymptomatic | θ1 | 5% | − | Li et al. [20] |

| developing symptoms | ||||

| Asymptomatic recovery | θ2 | 7 days | − | Li et al. [20] |

| period | ||||

| Symptomatic recovery period | r | 7 days | − | Li et al. [20] |

| Age specific hospitalization rate | hi | Uniformly distributed | Supp. Table 3 | [6,7] |

| Age specific recovery rate | φ1 | Supp. Table 3 | − | [6,7] |

| Age specific mortality rate | φ2=1-φ1 | Supp. Table 3 | − | [6,7] |

In this article, we use the daily number of cases data published by the CDC from January 3, 2020 to April 23, 2020 for the states of New York and Nebraska and calibrated the contact rate parameter value to achieve the reproductive number estimated. The cumulative number of cases over time for each state are presented in Fig. 4 , with respective time-dependent reproduction number estimates. The reproduction numbers in each state are estimated overtime with the uncertainty bounds, however, we have used the closest point estimates for each location. The estimates overtime are significantly different, and although they converge to value 1, they do not overlap. Then, using the theoretical formula for R(t), we have calibrated contact rates to achieve the observed reproduction of the cases estimated. See Supplemental Materials Table 2 for the values used for the model calibration.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative cases in New York and Nebraska by the end of April 2020 and time dependent estimates of reproduction numbers (time unit is day in these plots).

Table 2.

Total infection peak magnitude and peak timing with different school closure/ social distancing scenarios - no closure as baseline, 4 weeks closure, 8 weeks closure, 16 weeks closure, and 24 weeks closure in the medium infection rate.

| R0=2.1 | Duration of Closure | 1st Wave |

2nd Wave |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (%) | Peak Time | Peak (%) | Peak Time | ||

| No Intervention | 1.42% | 226th day | – | – | |

| Early Trigger (0.001) | 4 weeks | 0.0004% | 20th day | 1.43% | 283rd day |

| 8 weeks | 1.42% | 345th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 1.42% | 471st day | |||

| 24 weeks | 1.41% | 594th day | |||

| Late Trigger (0.5) | 4 weeks | 0.11% | 141st day | 1.30% | 289th day |

| 8 weeks | 1.27% | 356th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 1.26% | 488th day | |||

| 24 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| Very late Trigger (1.0) | 4 weeks | 0.22% | 156th day | 1.18% | 292nd day |

| 8 weeks | 1.10% | 359th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 1.09% | 501st day | |||

| 24 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

3.3. Disease spread model

We present the differential equation-based disease spread model constructed to simulate disease progression in the communities, and then we explain the triggering strategies used for social distancing policies and phase-based reopening mechanisms. Compartmental disease spread models are widely utilized in computational and mathematical epidemiology [1].

In these models all individuals act similarly but separately from each other in a homogeneously mixed population [10].

Here, in this study we use an age-structured, continuous time compartmental model that uses a population specific data and considers uncertainty on several input parameters. The eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7) model the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 disease in a given population and flow of individuals that moves from one disease state to another as given in Fig. 5 . They represent the disease progression for individuals who are first susceptible then exposed to the disease, and then become asymptomatic or symptomatically infectious. Asymptomatic infectious individuals either develop symptoms and become symptomatically infectious or recover from the disease without any symptoms. The symptomatic infectious individuals can either recover by themselves or be hospitalized. The hospitalized individuals can either recover or die from the disease.

Fig. 5.

Natural progression of COVID-19 with hospitalization.

These dynamics are modeled as following: S i(t) represents the number of susceptible individuals in the community at time t and for age group i, E i(t) represents the exposed individuals, while I Ai(t) is used for asymptomatic infectious individual and I Si(t) is used for the symptomatic infectious cases. R i(t) is used for the recovered cases in age group i and H i(t) represents the hospitalized cases at time t for the age group i. Finally D i(t) represents the number of deaths in each age group at time t. The force of infection for each age group is represented with λ i, and it is computed as where β ij represents the transmission between age groups i and j, c ij represents the contact rate between age groups i and j. N i(t) represents the total number of individuals at time t for age group i.Then, N i(t)=S i(t) + E i(t) + I Ai(t) + I Si(t) + H i(t) + R i(t) and N(t) = ∑j=1 k N i(t).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Each individual in the susceptible compartment is assumed to be susceptible to be exposed. This is modeled in Eq. 1 where for each age group i the corresponding susceptible group can get exposed with rate λ i. The decrements in the susceptible compartment for an age group are added to the exposed compartment for the corresponding age group in each simulation time step, which is a day. The decrements in exposed compartment are divided into two groups. First group shows symptoms and is moved to I Si(t); second group does not show any symptoms and is moved to I Ai(t) as given in Eq. 2. The decrements in the exposed compartment without any symptoms are added to infectious asymptomatic compartment. From this compartment, in each time step some individuals recover and hence removed from I Ai(t) for each age group i as shown in Eq. 3. Similarly for the symptomatic compartment decrements from the exposed compartment with symptoms are added to the symptomatic compartment as shown in Eq. 4. After the infectious period, the individuals in the symptomatic compartment either recover without any hospitalization or hospitalized for certain time period as given in Eq. 5. Hospitalized individuals either recover with a given rate as in Eq. 6 or die as given in Eq. 7.

Using the model presented above we have derived the basic reproductive number R 0 of the system, which is age specific, because the model is an age-structured one. Using the next generation operator, the theoretical expression for R 0 is derived as given below. See the Supplemental Materials 2 for the details of the derivation process and the proof of Proposition 1.

Now, the time dependent reproductive number i.e., R i(t) for age group i can be stated as follows:

We can now state the theoretical epidemic control condition.

Proposition 1

The epidemic control can be achieved if R i(t) ≤ 1 can be satisfied with social distancing policies for all age groups.

We calibrate the model based on the daily cases reported for considered communities to achieve the observed disease propagation and using the result stated in Proposition 1 we derive community specific analysis for evaluating the social distancing policies.

3.4. Modeling closure and reopening decisions

We evaluate a range of social distancing and reopening strategies for different scenarios for the transmissibility and estimated ranges of severity of the pandemic. Each social distancing policy alternative consists of a prevalence-based trigger and a fixed duration until a reopening decision is made as shown in Fig. 3.

Now we explain the modeling process of closure and reopening decisions. As defined earlier I Ai(t) represents the asymptomatic infections for age group i at time t and I Si(t) represents the symptomatic infections for age group i at time t. In our model, age groups i ∈ {k, a, e} are defined as k for “kids”, a for “adults”, and e for “elderly”. Let the function f(t) be the cumulative number of individuals infected at time t, which is computed as follows in Eq. 8:

| (8) |

We can mathematically define the trigger time for a social distancing policy to take place as follows in Eq. 9:

| (9) |

Given the policy trigger time, t ∗, below we show how contact rates c ij(t) for each age group changes at time t as the closure and reopening decisions are implemented.

3.4.1. Immediate reopening strategy

As the effects of policies would take some time to be observed, let δ be the implementation time after the trigger is hit. Let ε be the duration of time social distancing measures are in effect with minimal contact rates among age groups. Eq. 10 shows how contact rates change over time for this strategy.

| (10) |

3.4.2. Reopening with phases strategy

Let Δ1 be the duration of Phase 1 closure and Δ2 is the duration of Phase 2 closure. Eq. 11 shows how contact rates, c jk(t) change over time when this strategy is implemented.

| (11) |

4. Computational results

Using our compartmental model, we evaluate different social distancing strategies by varying two key parameters; namely, the threshold prevalence to start the social distancing policies and the length of social distancing. We also evaluate these strategies for different R 0 values, as we empirically find different growth rates for different states, in addition to a base case of globally estimated R 0 value of 2.1.

For example, the case reproduction dynamics in New York are different than those in Nebraska. Given the data we used, we estimate a higher transmission rate for New York (≈ 3.15), and Nebraska has a lower transmission rate (≈ 1.57) than the base scenario (R 0 = 2.1) at the time. Fig. 6a shows the simulated temporal dynamics of outbreak for three different growth rates with R 0 values of 1.57, 2.1 and 3.15, when no social distancing policy is implemented, i.e., labeled as “no intervention”.

Fig. 6.

The graph compares different R0 values, 1.57, 2.1 and 3.15. Lines indicate the median value and the shading indicates the inner 95% range of values of the 100 simulations. Peak timing and magnitude of the pandemic depends on the R0 values.

We find that the practical growth rate of the outbreak in a region directly affects the dynamics of the outbreak. Regions with a high transmission rate should expect to experience their peak to be observed much earlier than regions with a lower transmission rate. Similarly, the magnitude (i.e. peak height) of the outbreak is significantly higher for those regions with a high growth rate than those with a small growth rate, as expected.

Furthermore, when the same social distancing policies are employed for these different states, we observed different effects of interventions. For example, Fig. 6b compares one specific social distancing policy, i.e., triggering when the cumulative outbreak reaches 0.5% infections under different basic reproductive number scenarios. For states with a higher growth rate, the outbreak results in higher and earlier first peak, and an earlier second peak. For regions with a lower reproduction number, the social distancing trigger threshold is reached later and the observed peak is smaller. These simulations suggest that the same social distancing policy can have different effects on the evolution of the epidemic in different populations. Therefore, we evaluate each state separately. In the following sections, we evaluate a base scenario with (R 0 = 2.1), high transmission rate scenario with (R 0 = 3.15) and low transmission scenario with (R 0 = 1.57) to reflect the time dependent reproduction number estimates that use COVID-19 cumulative cases data from each state.

4.1. Base scenario

Early estimates for the characteristics of the COVID-19 virus suggest that the basic reproductive number would be greater than 2; however, wide uncertain rages are also reported [20]. Therefore, we use a base case scenario for the transmission dynamics with an R 0 value of 2.1. One critical question in mitigation efforts is to decide when to start the social distancing. Fig. 7 shows how applying two distinct trigger thresholds, i.e., 0.5% and 1%, can change the dynamics of the outbreak with a fixed duration of social distancing under the base case scenario with 8 weeks of social distancing. Specifically, the graph compares early trigger (0.5%) and late trigger (1%) options with no intervention. When the social distancing policy is triggered early (0.5%), the outbreak has a smaller first peak in the number of cases, and a much higher second peak. Conversely, when the social distancing policy is triggered late (1%), the outbreak has a higher first peak, and a smaller second peak. The early trigger results in an earlier second peak than when a late trigger is used. In both cases, the peaks are considerably dampened compared to the peak without any implemented social distancing implemented.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of triggers (1%and 0.5%) for social distancing policies with the no intervention strategy.

For an outbreak with baseline transmission rate our systematic and extensive simulations suggest the main benefit of social distancing is to buy time by delaying the peak as shown in Table 2. The length of the social distancing phase has minimal to no effect on the magnitude of the second wave. However, it directly changes the timing of the second wave. This time until the second wave could help public health officials to prepare for a second wave. The threshold used to trigger the social distancing policy has significant implications on the epidemic dynamics. Specifically, early triggers result in a small first wave and a larger second wave. Conversely, later triggers result in a relatively larger first wave, and smaller second wave when compared to the second waves of other policy triggering options. This result suggests that depending on the hospital bed and ICU capacity, early triggers or late triggers may be used to balance the magnitudes of the waves to mitigate and to manage the health care system capacity.

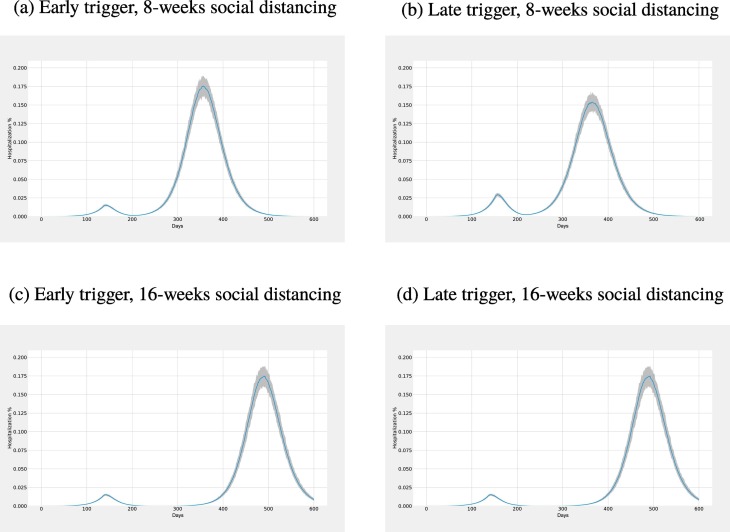

The number of hospitalizations also follows a similar trend as presented in Fig. 8 for social distancing. We compare hospitalization volumes for early trigger and late trigger with 8 weeks and 16 weeks of social distancing. Using an earlier trigger results in a smaller initial peak in hospitalizations than a later trigger. Conversely, the second peak is observed to be higher when an early trigger is used instead of the later trigger. The length of the social distancing policy merely delays the second peak, both for early and late triggers, with no material impact on the size of the second peak. Using a smaller prevalence value for triggering the policy results in a smaller first peak instead of the later trigger; however, the second peak for the early trigger is larger than that of the late trigger. The length of the social distancing again affects the timing of the second peak.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of hospitalization volumes for early trigger and late trigger (i.e., columns) for 8 weeks and 16 weeks closures (i.e., rows).

4.2. Higher transmission scenario

While some highly dense US states observed faster growth in the number of cases, e.g., New York and California, some states with lower population density observed steep and later increases in the cases. Therefore, we simulate a scenario with a higher transmission rate, which is achieved with R 0 = 3.15. Similar to the base case scenario, simulations suggest the main benefit of social distancing is to buy time by delaying the peak as shown in Table 3 . The length of the social distancing phase has minimal to no effect on the magnitude, i.e., height of the peak of the second wave. However, it directly changes the timing of the second wave. The magnitudes of the second peaks for the high transmission scenario for all trigger options is more than two times larger than those of the baseline transmission scenario.

Table 3.

High Infection rate, total infection peak magnitude and peak timing with different school closure/ social distancing scenarios - no closure as baseline, 4 weeks closure, 8 weeks closure, 16 weeks closure, and 24 weeks closure.

| R0=3.15 | Duration of Closure | 1st Wave |

2nd Wave |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (%) | Peak Time | Peak (%) | Peak Time | ||

| No Intervention | 3.52% | 130th day | – | – | |

| Early Trigger (0.001) | 4 weeks | 0.0008% | 23rd day | 3.52% | 168th day |

| 8 weeks | 3.50% | 208th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 3.50% | 289th day | |||

| 24 weeks | 3.48% | 368th day | |||

| Late Trigger (0.5) | 4 weeks | 0.30% | 89th day | 3.12% | 172nd day |

| 8 weeks | 2.97% | 216th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 2.93% | 301st day | |||

| 24 weeks | 2.92% | 387th day | |||

| Very late Trigger (1.0) | 4 weeks | 0.57% | 97th day | 2.76% | 174th day |

| 8 weeks | 2.54% | 220th day | |||

| 16 weeks | 2.46% | 312nd day | |||

| 24 weeks | 2.44% | 404th day | |||

Depending on the length of the implemented social distancing, public health officials gain time until the second wave that ranges from one month, when the least aggressive scenario is employed, to nine months, when the most aggressive scenario is employed. Such a delay in the second peak could enable an increase in hospital capacity, explorations for vaccinations, and improved public health awareness.

4.3. Lower transmission scenario

For an outbreak with a low transmission rate our simulations suggest the main benefit of social distancing, similar to the baseline scenario and the high transmission scenario, is to buy time by delaying the peak as shown in Table 4 . However, for the low transmission scenario the magnitude of the peak, even with no intervention, is small compared to the high and baseline transmission rates. Furthermore, the timing of the peak for low transmission is much later than that of baseline transmission (i.e., 432nd day versus 226th day). In fact, the hospital capacity might already be sufficient or could be increased until the peak time to cover the 0.39% peak magnitude. Overall, the closure length should depend on the extra capacity needed to handle the patients during the peak.

Table 4.

Total infection peak magnitude and peak timing with different social distancing scenarios - no closure as baseline, 4 weeks closure, 8 weeks closure, 16 weeks closure, and 24 weeks closure.

| R0=1.5 | 1st Wave |

2nd Wave |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (%) | Peak Time | Peak (%) | Peak Time | ||

| No Intervention | 0.39% | 432nd day | – | – | |

| Early Trigger (0.001) | 4 weeks | 0.0003% | 19th day | 0.38% | 538th day |

| 8 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 16 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 24 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| Late Trigger (0.5) | 4 weeks | 0.045% | 260th day | 0.34% | 551st day |

| 8 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 16 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 24 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| Very late Trigger (1.0) | 4 weeks | 0.08% | 294th day | 0.30% | 556th day |

| 8 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 16 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

| 24 weeks | *out of 600 range | ||||

4.4. Evaluating closure/reopening decisions

Because our compartmental model is age structured, it allows us to look at each age group separately in addition to the overall population. This feature enables us to explore the vulnerability of high risk population. Therefore, we here compare cumulative attack rate (CAR), percentage of deaths and peak hospitalizations in each age group separately for all transmission scenarios. In Fig. 9 , we present percentage of deaths for each age group for the different transmission scenario considered. We find that the burden of the pandemic on elderly population is the worst in all potential transmission scenarios. Specifically, as the transmission rate increases, cumulative death percentage of for the elderly population increases drastically. This suggests that for dense regions, high-risk groups should be given more attention.

Fig. 9.

Cumulative Deaths (%) for different R0 values for each age group; social distancing is triggered when cumulative prevalence reaches 0.5% for 8 weeks.

On the other hand, the early trigger and late trigger would result in different death tolls. We compare different closure strategies for all levels of social distancing along with different trigger levels (See Supplemental Materials 3 and Table 5 ). Early trigger results in a relatively lower death rate in a low transmission rate while a late trigger results in a larger death rate as shown in Table 5. This result is presented for 16 weeks of social distancing. However, the expected deaths for the base scenario and higher transmission rate scenarios would be lower when later trigger levels are used. Supplemental Materials 3 shows that until the 16 weeks of social distancing (1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks) in all transmission rates, death percentage decreases as we increase the trigger level.(See Supplemental Materials 3 and Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 , 7, 8 and 9).

Table 5.

Death rate, maximum hospitalization rate, Cumulative attack rate (CAR) and Cumulative attack rate including the asymptomatic cases with 16 weeks of social distancing.

| R0 | Trigger % | Death(%) | Peak Hospitalization (%) | CAR | CAR (+asymptomatic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.57 | – | 0.135 | 0.051 | 18.203 | 22.191 |

| 1.57 | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.048 | 0.060 |

| 2.57 | 0.5 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.837 | 1.020 |

| 1.57 | 1.0 | 0.012 | 0.010 | 1.613 | 1.966 |

| 2.1 | – | 0.270 | 0.197 | 33.587 | 40.914 |

| 2.1 | 0.001 | 0.268 | 0.197 | 33.453 | 40.812 |

| 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.261 | 0.174 | 32.618 | 39.797 |

| 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.251 | 0.153 | 31.550 | 38.450 |

| 3.15 | – | 0.438 | 0.522 | 49.125 | 59.829 |

| 3.15 | 0.001 | 0.437 | 0.521 | 49.147 | 59.865 |

| 3.15 | 0.5 | 0.428 | 0.436 | 48.147 | 58.650 |

| 3.15 | 1.0 | 0.421 | 0.365 | 47.240 | 57.547 |

Table 6.

Highlight of different scenarios (i.e., different closure triggers and lengths) for the three transmission rates which minimizes both the cumulative attack rate (CAR) and total death toll, separately. The bold rows indicate the scenarios for each transmission rate, that minimizes these objectives. Note that independently minimizing CAR and minimizing total deaths result in the same scenarios.

| Objectives |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. CAR | Min. Death | |||||

| Threshold | Closure | Reduction (%) | Threshold | Closure | Reduction (%) | |

| R0 = 1.57 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.296 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.326 |

| R0 = 1.57 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.779 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.791 |

| R0 = 1.57 | *out of 600 day range | |||||

| R0 = 1.57 | *out of 600 day range | |||||

| R0 = 2.10 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.029 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.030 |

| R0 = 2.10 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.040 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.041 |

| R0 = 2.10 | 1% | 16 weeks | −0.061 | 1% | 16 weeks | −0.070 |

| R0 = 2.10 | 1% | 24 weeks | −0.749 | 1% | 24 weeks | −0.781 |

| R0 = 3.15 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.027 | 1% | 4 weeks | −0.027 |

| R0 = 3.15 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.033 | 1% | 8 weeks | −0.034 |

| R0 = 3.15 | 1% | 16 weeks | −0.038 | 1% | 16 weeks | −0.037 |

| R0 = 3.15 | 1% | 24 weeks | −0.041 | 1% | 24 weeks | −0.041 |

To control the rapidly growing outbreak across the US, public health officials and governments issued shelter-in-place orders. Although social distancing and shelter-in-place orders help mitigate the outbreak, they have significant economic and social costs. For example, in the US during the social distancing for COVID-19, the unemployment rates have spiked. To identify possible reopening strategies, we evaluate a two-phased reopening strategy. We compare this strategy to two basic alternatives: (1) No closures (i.e., no social distancing); (2) Immediate reopening (i.e., no phases).

For example, Fig. 10 shows the three different scenarios: (1) No closures, (2) Immediate reopening, and (3) Reopening with Phases for an outbreak with a medium growth rate. The no-closures strategy is without any implemented social distancing, indicated by the red line. The immediate reopening strategy returns to original contact rates for all age groups immediately after 8 weeks of closure shown by the yellow line. The reopening with phases strategy, indicated by the blue line in Fig. 10a, corresponds to reopening with phases of an 8-week length, i.e., after 8 weeks of social distancing an 8-week long phase 1 starts with an increase in the contact rate with a certain ratio. Phase 1 is followed by another 8-week long phase 2, where contact rates increase even more. Finally, after phase 2, original contact rates are restored (See Supplemental Materials Table 2 for the corresponding contact rates). In Fig. 10a, we observe that the phased reopening results in smaller outbreak sizes (i.e., smaller peak magnitude) than both the no-closure strategy and the immediate reopening strategy. We have also evaluated reopening strategies with 24-week long phases. Fig. 10b shows that the burden of the pandemic is further mitigated using longer term phases.

Fig. 10.

Prevalence curve comparison in “No closure”, “Immediate reopening” and “Reopening with Phases” for medium growth rate. (a) 8-week reopening strategy, (b) 24-week reopening strategy, time unit is in days.

Fig. 10 shows the different scenarios for the base transmission scenario and two possible lengths of reopening phases. We also show outbreaks with different growth rates and with other possible lengths of reopening phases. For example, Fig. 11 shows different possible lengths of reopening phases for an outbreak with different transmission rates. For all lengths considered, the longer the phase duration is, the more dampened the outbreak burden, as well as the further in time the peak is observed. For example, the peak is reduced more than half with 24-week long phases instead of 4-week long phases. This shows the effect on hospital capacity in terms of how much it could be enhanced with the delay of the peak by social distancing and the size of the second peak as a result of the length of social distancing.

Fig. 11.

Comparison of the different reopening strategies for R0: 3.15, R0: 2.1 and R0: 1.57. 8 weeks of closure followed by (a) 4 weeks in Phase 1 and Phase 2, (b) 8 weeks in Phase 1 and Phase 2, (c) 16 weeks in Phase 1 and Phase 2 (d) 24 weeks in Phase 1 and Phase 2.

For high transmission rate and for all lengths of social distancing considered, the longer the phase windows the more the reduction in the epidemic size is achieved. Though, surprisingly, the observed peak time for different reopening phases shifts marginally. Different possible duration of reopening phases for the pandemic with smaller growth rate also shown in Fig. 10. Unsurprisingly, the overall outbreak is much smaller. Specific to this scenario, reopening phases with 16-week and 24-week long of closure delays the peak timing even beyond the next 600 days. Arguably, the healthcare system could absorb a reopening with the minimum length considered, i.e., 4-week long closure period. In other words, we note that for regions with low transmission rate with enough hospital capacity, reopening relatively sooner might be a feasible strategy. Different scenarios are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 in Supplemental Materials.

Table 6 summarizes possible scenarios that minimize expected Cumulative Attack Rate (CAR) and the expected total death rate under different considered transmission cases. For a lower transmission rate, an 8-week closure results in a significantly bigger reduction in CAR as well as a total death toll than a 4-week closure. For a medium transmission rate, i.e., the baseline, we observe that a 24-week closure results in a significantly higher reduction in CAR as well as total death toll. For a higher transmission rate, although a 24-week closure results in highest reduction in CAR as well as a total death toll, the overall reduction magnitudes are very small. Furthermore, the marginal reduction due to additional weeks to closure appears to be negligible. To achieve reductions similar to other transmission rates longer closure scenarios should be considered.

4.5. Evaluating phase based reopening decisions

As for reopening, we also show that reopening with phases might be more crucial in dense populations such as New York's where higher transmission is estimated. An especially, long time window reopening can significantly reduce the burden of the outbreak, which makes it easier for the healthcare system. However, in places where lower transmission rates are estimated, e.g., in Nebraska, reopening with phases will also be useful but not as critical as in New York. Even the shortest time window reopening strategies results with cases that the healthcare system can absorb. To summarize, one size fits all reopening policies that treat the entire population as one is liable to result in inefficiencies. Premature reopening strategies may result in excessive overload in hospitalizations and ICU capacity that creates a deadlock in healthcare system. Reopening strategies with phases might provide a feasible middle ground to manage the trade-off between improving the economy and giving more time to health officials to improve healthcare capacity and develop vaccines.

Early reopening might result in an increased number of infections and death tolls in the dense areas and late reopening might result in economic loss in comparatively less dense areas. Each region should consider its own hospital/ICU capacity and other limitations while easing social distancing. Our model provides a framework to consider various trade-offs (e.g., the length of social distancing vs the number of hospitalizations) at a local level.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we present a decision analytic framework which presents an efficient tool to assess the effectiveness of early social distancing measures in communities with different population characteristics. We use a compartmental simulation model for the COVID-19 pandemic, which is age structured with three age groups, (i.e., kids, adults, and elderly). We perform systematic and extensive simulations to evaluate social distancing and reopening scenarios for regions with different disease dynamics. Specifically, we find that the effective growth rate of the disease is different for different regions in the US. For example, New York, i.e., high density urban population, has a higher transmission rate, whereas Nebraska, i.e., low density more rural population, has a lower transmission rate than the considered base case. Our simulations suggest that depending on the estimated transmission rate, the magnitude and the timing of the peak cases would vary across regions; therefore, the optimal mitigation policies may vary.

Furthermore, we present the impact of various social distancing policies on the overall death toll and the enhanced hospital capacity in a region. Specifically, we consider triggering social distancing early (0.001%), late (0.5%), or very late (1%). We find that early trigger social distancing strategies result in small death tolls; however, there are relatively larger second waves. Conversely, late trigger social distancing strategies result in higher initial death tolls but relatively small second waves. This study shows that policy makers should expect multiple waves of cases as a result of/due to the social distancing policies implemented when there are no vaccines available for mass immunization and appropriate antiviral treatments. Social distancing policies only provide time for managing the cases in the population until these pharmaceutical interventions become available. We have shown that with the higher transmission scenario it is better to use a relatively later trigger with a longer closure duration, if the goal is to minimize the total death toll. Also, our results show that social distancing is comparatively more effective when there is lower transmission as it results in a delayed peak. This delay buys time to implement pharmaceutical interventions mentioned above.

Finally, we note that there is so much unknown about COVID-19. Although we expect the relative comparisons of different strategies should still apply, the results of this work should be considered within the limitations of the model parameters. Our results are based on parameters obtained mainly from CDC reports and early estimates of the disease. As the parameters are refined, our projections will be improved. The number of hospitalizations and deaths will also depend on how effectively we protect our high-risk populations. In the reopening scenarios, phase 1 and phase 2 are solely based on contact rate relaxations in social distancing. Depending on the current situation, the restrictions and contact rates may have been tightened to avoid overwhelming local capacities. As a future work, we are planning to incorporate mechanisms in the model for controlling the COVID-19 spread proactively, so that we could control the hospital capacity and actively use the risk-based guidelines to manage the pandemic. Also, community compliance data of social distancing policies can be gathered and incorporated into our models. Lastly, the presented decision framework can be utilized with newly emerging epidemic data to simulate further potential public health policies which may be considered with new pharmaceutical supplies, e.g., vaccines and antiviral treatments.

Biographies

Dr. Zeynep Ertem is an Assistant Professor in the Industrial Engineering Department at SUNY Binghamton. Her expertise is in data analytics in healthcare systems, epidemic disease modeling, network optimization, discrete optimization, social networks and health systems optimization. Prior to joining SUNY Binghamton, she was an adjunct professor of Data Sciences and Operations department at Marshall School of Business at University of Southern California. She also served as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin in the Department of Data Science and Statistics. She completed her Ph.D. in Industrial and Systems Engineering at Texas A&M University after obtaining her B.S. degree in Industrial Engineering from the Middle East Technical University in Ankara with a minor in Mathematics. Her recent projects were not only published in high-impact journals such as PLOS Computational Biology, Social Networks, and Journal of Global Optimizations but also highlighted by local and national news outlets in the US.

Dr. Özgür M Araz is Associate Professor in the Supply Chain Management and Analytics Department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and a R. Daugherty Water for Food Institute faculty fellow. His research interests include systems simulation, business analytics, healthcare operations, public health informatics. His research had been supported by NIH, VA hospitals, HDR company, Boys Town, Nebraska Medicine and the University of Nebraska. Before joining the College of Business at UNL, he served as a faculty member of the College of Public Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC). He received his Ph.D. in Industrial Engineering from the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University and was a postdoctoral research fellow at the Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics of The University of Texas at Austin. His research appeared in journals such as Decision Sciences, Production and Operations Management, Decision Support Systems, International Journal of Production Economics, Annals of Operations, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Medical Care, Healthcare Management Science, among many other prestigious journals. He serves as Associate Editor for Decision Sciences, Transportation Research Part-E and also IISE Transactions of Healthcare Systems Engineering. He is the Area Editor for Public Health Informatics in Health Systems journal.

Dr. Mayteé Cruz-Aponte is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Mathematics – Physics in the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey where she established a Biomathematics Lab. She received an education in the public school system in Puerto Rico. She earned a Bachelor in Science in Computational Mathematics from the University of Puerto Rico in 2002, a Masters in Science in Mathematics from the University of Iowa in 2004 and a Ph.D. in Applied Mathematics for the Life and Social Sciences from Arizona State University in 2014. At her Biomathematics Lab, Dr. Cruz-Aponte research focuses on mathematical epidemiology and the spread of communicable diseases.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2021.113630.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Anderson Roy M., May R.M. Oxford Science Publication; New York: 1991. Infectious Diseases of Humans. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araz Ozgur M., Damien Paul, Paltiel David A., Burke Sean, van de Geijn Bryce, Galvani Alison, Meyers Lauren Ancel. Simulating school closure policies for cost effective pandemic decision making. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):449. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araz Ozgur M., Lant Tim, Fowler John W., Jehn Megan. Simulation modeling for pandemic decision making: a case study with bi-criteria analysis on school closures. Decis. Support. Syst. 2013;55(2):564–575. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araz Ozgur M., Choi Tsan-Ming, Olson David L., Salman F. Sibel. Role of analytics for operational risk management in the era of big data. Decis. Sci. 2020;51(6):1320–1346. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora Hina, Raghu T.S., Vinze Ajay. Resource allocation for demand surge mitigation during disaster response. Decis. Support. Syst. 2010;50(1):304–315. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC COVID Data Tracker. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases [Date retrieved: June, 202]

- 7.CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) how COVID-19 spreads. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html Date retrieved: March 13, 2020.

- 8.Ciavarella C., Fumanelli L., Merler S., Cattuto C., Ajelli M. School closure policies at municipality level for mitigating influenza spread: a model-based evaluation. BMC Infect Dis. 2016:16. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1918-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtemanche Charles, Garuccio Joseph, Le Anh, Pinkston Joshua, Yelowitz Aaron. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Aff. 2020;39(7) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitrov Nedialko, Goll Sebastian, Meyers Lauren Ancel, Pourbohloul Babak, Hupert Nathaniel. Optimizing tactics for use of the US antiviral strategic national stockpile for pandemic (H1N1) influenza, 2009. PLoS Currents. 2009;1 doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duijzer Lotty E., van Jaarsveld Willem L., Wallinga Jacco, Dekker Rommert. Dose-optimal vaccine allocation over multiple populations. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018;27(1):143–159. doi: 10.1111/poms.12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duijzer Lotty Evertje, van Jaarsveld Willem, Dekker Rommert. The benefits of combining early aspecific vaccination with later specific vaccination. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018;271(2):606–619. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fumanelli Laura, Ajelli Marco, Merler Stefano, Ferguson Neil M., Cauchemez Simon. Model-based comprehensive analysis of school closure policies for mitigating influenza epidemics and pandemics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12(01):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gojovic M.Z., Sander B., Fisman D., Krahn M.D., Bauch C.T. Modelling mitigation strategies for pandemic (H1N1) 2009. CMAJ. 2009;181(10):673–680. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths Jeff, Lowrie Dawn, Williams Janet. An age-structured model for the AIDS epidemic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000;124(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta Ashish, Sharda Ramesh. Improving the science of healthcare delivery and informatics using modeling approaches. Decis. Support. Syst. 2013;55:423–427. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauer Stephen A., Grantz Kyra H., Bi Qifang, Jones Forrest K., Zheng Qulu, Meredith Hannah R., Azman Andrew S., Reich Nicholas G., Lessler Justin. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee Bruce Y., Brown S.T., Cooley P., et al. Simulating school closure strategies to mitigate an influenza epidemic. J. Pub. Health Manag. Prac. 2010;16(3):252–261. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181ce594e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Qun, Guan Xuhua, Wu Peng, Wang Xiaoye, Zhou Lei, Tong Yeqing, Ren Ruiqi, Leung Kathy S.M., Lau Eric H.Y., Wong Jessica Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Ruiyun, Pei Sen, Chen Bin, Song Yimeng, Zhang Tao, Yang Wan, Shaman Jeffrey. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science. 2020;368(6490):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linton N.M., Kobayashi T., Yang Y., Hayashi K., Akhmetzhanov A.R., Jung S.M., Yuan B., Kinoshita R., Nishiura H. Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(538) doi: 10.3390/jcm9020538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizumoto Kenji, Kagaya Katsushi, Zarebski Alexander, Chowell Gerardo. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the diamond princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(10):2000180. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mossong Joël, Hens Niel, Jit Mark, Beutels Philippe, Auranen Kari, Mikolajczyk Rafael, Massari Marco, Salmaso Stefania, Tomba Gianpaolo Scalia, Wallinga Jacco, et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadj M., Maedche A., Schieder C. The effect of interactive analytical dashboard features on situation awareness and task performance. Decis. Support. Syst. 2020;135:113322. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2020.113322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez-Nafarrate Adrian, Araz Ozgur M., Fowler John W. Decision assessment algorithms for location and capacity optimization under resource shortages. Decis. Sci. 2021;52(1):142–181. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sander Beate, Kwong Jeffrey C., Bauch Chris T., Maetzel Andreas, McGeer Allison, Raboud Janet M., Krahn Murray. Economic appraisal of Ontario’s universal influenza immunization program: a cost-utility analysis. PLoS Med. 2010;7(4):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teytelman Anna, Larson Richard C. Modeling influenza progression within a continuous-attribute heterogeneous population. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012;220(1):238–250. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Thompson H., Walker P.G.T., Fu H., Dighe A., Griffin J.T., Baguelin M., Bhatia S., Boonyasiri A., Cori A., Cucunuba Z., FitzJohn R., Gaythorpe K., Green W., Hamlet A., Hinsley W., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Riley S., van Elsland S., Volz E., Wang H., Wang Y., Xi X., Donnelly C.A., Ghani A.C., Ferguson N.M. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material