In May 2021, concerns about possible cases of myocarditis following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination were raised by the European Medicines Agency safety committee [1].

We analysed reporting of myocarditis (myocarditis preferred term level using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) associated with vaccines (J07 using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) versus all other drugs, worldwide, from inception (1967) to 7 May 2021, in the international pharmacovigilance database VigiBase. We used the information component (IC), an indicator value for disproportionate Bayesian reporting comparing observed and expected values to find signals for associations between drugs and adverse events [2]. IC025 is the lower end of the IC 95% credibility interval. A positive IC025 is deemed significant. We used clozapine and atorvastatin as positive and negative controls, respectively. Individual case reviews of each report of suspected COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis were then performed. Suspected myocarditis was classified according to the consensus definition of drug-induced autoimmune myocarditis as possible, probable or definite, based on the presence or absence of compatible clinical symptoms, electrocardiogram, abnormal troponin concentrations, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, endomyocardial biopsy results or exclusion of coronary artery disease, when available [3].

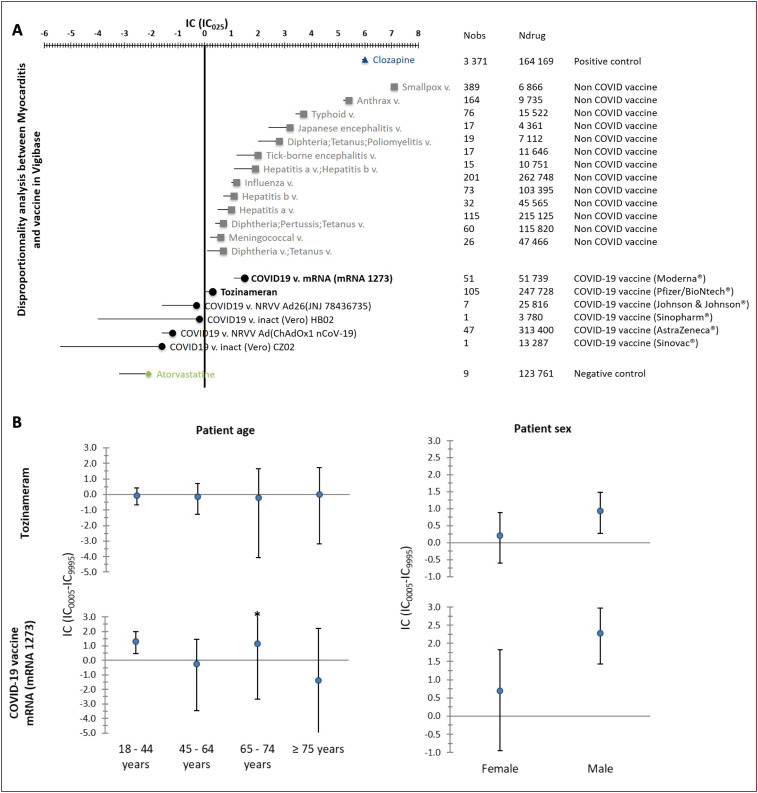

VigiBase contained a total of 25,728,751 adverse drug reaction reports, including 8664 reports of myocarditis, of which 1251 involved a suspected culprit vaccine. Among these latter reports, 214 (17.1%) were associated with COVID-19 vaccines. Only messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines, including mRNA1273 (Moderna®, n = 51, IC025 = 1.1) and tozinameran (Pfizer/BioNTech®, n = 105, IC025 = 0.05) were significantly associated with myocarditis, whereas other types of COVID-19 vaccine were not (Fig. 1 ). The magnitude of the associations with liable non-COVID-19 vaccines and positive and negative controls are also shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Information component (IC) and its 95% credibility interval lower endpoint (IC025) comparing myocarditis associated with vaccines (J07 using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) versus the full VigiBase database (until 05 July 2021). A positive IC025 value (> 0) is the traditional threshold used in statistical signal detection with VigiBase. A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and non-COVID-19 vaccines significantly associated with myocarditis are in black (bold) and grey, respectively; COVID-19 vaccines non-significantly associated with myocarditis are in black (non-bold). B. Subgroup analysis of IC as a function of sex and age for COVID-19 liable vaccines. mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid; Ndrug: the number of reports for the drug, regardless of the adverse drug reaction; Nobs: the actual number of reports observed for the drug-adverse drug reaction combination; v.: vaccine.

The median age of patients with COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis was 35 years (interquartile range 25–50 years) and 131/205 (63.9%) were male; five patients died. Disproportional association as a function of age and sex group showed over-reporting in males for the mRNA1273 and tozinameran vaccines, and in younger people for the mRNA1273 vaccine (Fig. 1). Of importance, 188/214 (88%) patients were free from any other reported medication. No case of concurrent eosinophilia was reported. Associated pericarditis was reported in 47/214 (22%) cases. The median time to onset between last dose of vaccine received and the adverse event was 3 days (interquartile range 1–6 days; n available = 202). Notably, sufficient data were available to classify 23 cases as definite, 16 as probable and 46 as possible myocarditis. No patient with definite myocarditis died.

Vaccines are a known, but rare, cause of myocarditis, considering the population exposed [4]. Despite the inherent limitation of such an analysis, this report suggests that, similar to other vaccines, mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are associated with myocarditis. We acknowledge several sources of bias caused by the nature of the pharmacovigilance database, including underreporting, associated with halo bias and a lack of detailed information on the exposed population for calculation of incidence. However, given that approximately half a billion patients have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine at the time of this analysis, we strongly believe that these results do not change the clear and favourable balance of benefit over risk for COVID-19 vaccines. Nevertheless, physicians should be aware of this rare but potentially life-threatening adverse event, with early recognition being critical to provide appropriate care [5].

Sources of funding

None.

Disclosure of interest

M.K. Consulting fees from the companies Sanofi, Bayer and Kiniksa. Research grants from the Federation Française de Cardiologie and the French Health Ministry.

J.-E.S. Consulting fees from the company BMS. Research grants from the companies BMS and Novartis, and from the Federation Française de Cardiologie, the Société Française de Cardiologie, INSERM and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche.

K.B. declares that he has no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

The supplied data came from a variety of sources. The likelihood of a causal relationship was not the same in all reports. The information does not represent the opinion of the World Health Organization.

References

- 1.EMA . 2021. Meeting highlights from the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) 3–6 May 2021.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/meeting-highlights-pharmacovigilance-risk-assessment-committee-prac-3-6-may-2021 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem J.E., Manouchehri A., Moey M., et al. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30608-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaca M.P., Olenchock B.A., Salem J.E., et al. Myocarditis in the Setting of Cancer Therapeutics: Proposed Case Definitions for Emerging Clinical Syndromes in Cardio-Oncology. Circulation. 2019;140:80–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engler R.J., Nelson M.R., Collins L.C., Jr., et al. A prospective study of the incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis and new onset cardiac symptoms following smallpox and influenza vaccination. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kociol R.D., Cooper L.T., Fang J.C., et al. Recognition and Initial Management of Fulminant Myocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e69–e92. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]