Abstract

Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) are the two most aggressive forms of non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs). Spontaneous remission of DLBCL is a rare phenomenon. Immune system activation has been observed to play a significant role in the regression of untreated disease on some occasions. We present a case of DLBCL in a 75-year-old male patient who has been free of disease for two months without any treatment due to possible immune-related mechanism, but later he presented with FL.

Keywords: follicular lymphoma, r-chop therapy, hiv lymphoma, non-hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, spontaneous regression

Introduction

Lymphomas are the malignancies of the lymphoid system that can arise from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes or natural killer (NK) cells depending on their stages of maturation. They are categorized into Hodgkin lymphoma and non-lymphoma Hodgkin (NHL). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL) are the most common forms of NHLs. There are roughly 150,000 new cases of DLBCL diagnosed globally each year [1]. The disease is seen frequently in whites followed by African Americans and Asians, with a male preponderance. The overall incidence of NHL or DLBCL increases exponentially with age.

DLBCL commonly presents as lymphadenopathy or rapidly growing mass with B symptoms, which include fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Extranodal sites are seen in approximately 40% of patients with DLBCL [2]. The most common sites of extranodal spread of disease are the gastrointestinal tract, skin, bones, head and neck, central nervous system, skeletal system, and testicles [3]. Due to the hematogenous spread, DLBCL can remain asymptomatic until a late disease stage, and symptoms mainly depend on the site of involvement.

We present an unusual case of a 75-year-old male patient diagnosed with DLBCL harboring poor prognostic features of MYC and BCL2 protein coexpression showing spontaneous regression of lymphadenopathy without any intervention or treatment and later presenting with FL.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old Caucasian male was diagnosed with DLBCL based on clinical and diagnostic evaluation. Prior to his confirmed diagnosis, on routine physical evaluation at an outpatient setting he was observed to have an axillary lymphadenopathy that was associated with right-sided hilar adenopathy on chest X-ray. The patient denied having complaints of weight loss, fever, chills, night sweats, shortness of breath, or chest pain in the past. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, aortic stenosis, and coronary artery disease (CAD). The patient also underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for his aortic stenosis and CAD.

During the evaluation for DLBCL, the patient underwent positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which revealed an enlarged and increased standardized uptake value (SUV) in the right hilar lymph node (Figure 1), right axillary lymph node (Figure 2), inter-aortocaval lymph node, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Similar enlargement of axillary node and hilar nodes with splenomegaly was observed on computed tomography (CT) scan (Figures 3-5).

Figure 1. PET scan showing right hilar mass (green arrow).

Figure 2. PET scan showing right axillary mass (green arrow).

Figure 3. CT scan showing axillary mass/lymphadenopathy (red arrow).

Figure 4. CT scan showing right hilar mass.

Figure 5. CT scan showing splenomegaly.

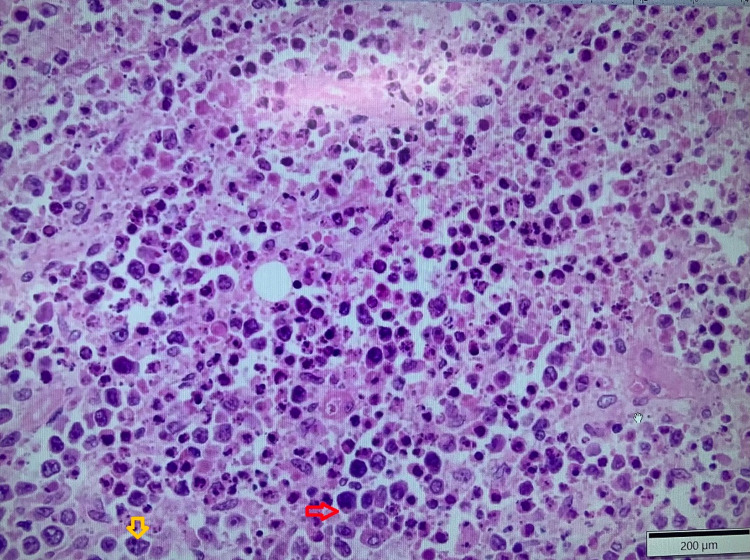

Excisional biopsy of the right axillary mass was performed, which showed features of DLBCL (Figure 6). Furthermore, flow cytometry demonstrated a cluster of differentiation (CD) 5 negative and CD10 negative clonal B-cell population with lambda light chain restriction confirming B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Right upper lobe fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was negative for malignancy. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis revealed abnormal cell line positive for BCL6 and negative for MYC and BCL2 rearrangements.

Figure 6. Axillary lymph node biopsy.

Large lymphocytes (red arrow), nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (yellow arrow) can be seen.

Interval resolution of previously seen hypermetabolic right axillary node (Figure 7), right hilar node (Figure 8), and abdominal lymphadenopathy was noticed on its own on PET scan after two months from the date of diagnosis without any form of treatment, which was observed to be an unusual phenomenon.

Figure 7. PET scan showing no axillary mass.

Figure 8. PET scan showing no SUV/FDG uptake in the hilar region.

SUV, standardized uptake value; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose

Later, on follow-up PET scan, multiple new foci of increased SUV in the right submental lymph node (Figure 9), spleen, and left femoral shaft were observed.

Figure 9. PET scan showing submental lymhadenopathy.

FDG uptake is seen in the right submental lymph node

FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose

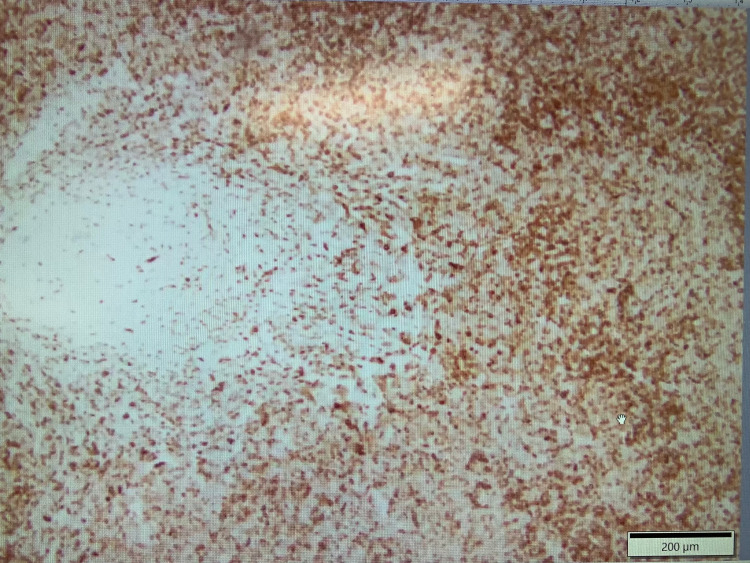

Subsequently, excisional biopsy of the submental lymph node confirmed CD21 positive (Figures 10, 11) and BCL2 negative stage 3B FL. Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) therapy is now planned for the patient based on his complaints of persistent fatigue and newly diagnosed aggressive FL. The patient's lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were also persistently elevated on subsequent disease monitoring.

Figure 10. Submental biopsy showing follicular lymphoma (CD21 positive).

Figure 11. Submental lymph node biopsy showing follicular lymphoma (CD21 positive with dendritic meshwork pattern).

Discussion

The Ann Arbor staging system (Table 1) illustrates the extent of disease, age, presence of extranodal involvement, elevated LDH, and performance status based on the international prognostic index (IPI), which are all prognostic factors in overall survival in B-cell NHL [4].

Table 1. Ann Arbor staging system: lymphoma.

| Stage | Clinical manifestation |

| I | Single lymph node or single extra-lymphatic organ |

| II | >2 lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm |

| III | Both sides of the diaphragm involved; may have spleen or local tissue involvement |

| IV | Multiple/disseminated foci involved with >1 extra-lymphatic organs (i.e., bone marrow) |

The standard first-line chemotherapy treatment of DLBCL is the combination of R-CHOP. Although DLBCL can be cured with first-line chemotherapy in more than half of all patients, up to 50% of patients do not respond to initial treatment or relapse after showing preliminary response [5]. Spontaneous regression of lymph nodes and remission of disease in aggressive lymphomas such as DLBCL and FL is a rare phenomenon, and data are limited in the medical literature. The physiology of spontaneous remission of the disease remains unknown. Regression is more commonly observed with groups of tumors such as embryonal tumors in children, carcinoma of the breast, adenocarcinoma of the kidney, neuroblastoma, malignant melanoma, sarcomas, and carcinoma of the bladder and skin [6]. Armstrong et al. hypothesized that immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome following the initiation of antiretroviral therapy has played a role in the regression of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐associated plasmablastic lymphoma of the oral cavity [7]. The phenomenon of regression in lymphoma has also been postulated to be immune‐mediated secondary to activation from viruses, such as Epstein‐Barr virus, or local trauma from the biopsy site [7-9].

Conclusions

The patient in our case opted for surveillance and showed no evidence of disease recurrence at two months since the biopsy results of DLBCL. The remission occurred via an unknown mechanism, possibly related to immune system activation. However, FL at a different site with a history of DLBCL in remission in the same patient is also an uncommon phenomenon. Thus, this case provides further insight into the role of immune system activation in regression of aggressive lymphomas such as DLBCLs or FLs.

Acknowledgments

The completion of this undertaking could not have been possible without the participation and assistance of so many people whose names may not all be enumerated. Their contributions are sincerely appreciated and gratefully acknowledged. To all relatives, friends, and others who in one way or another shared their support, either morally, financially, and physically, thank you.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sehn LH, Salles G. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:842–858. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2027612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Primary extra-nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a prognostic analysis of 141 patients. Shen H, Wei Z, Zhou D, et al. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:1602–1614. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sites of extranodal involvement are prognostic in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Olszewski AJ. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:310–314. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, et al. Blood. 2014;123:837–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-524108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spontaneous remission and concomitant progression in a patient with DLBCL. Han EJ, Kim J, Park SY, O JH. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:950. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10110950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Immunity over inability: the spontaneous regression of cancer. Jessy T. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:43–49. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spontaneous regression of an HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in the oral cavity: a case report. Armstrong R, Bradrick J, Liu YC. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1361–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, with spontaneous regression after biopsy. Marrero-Alemán G, Montenegro-Dámaso T, Peñate Y. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:785–787. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spontaneous regression of extranodal malignant lymphoma occurred in the gingiva. Koga M, Kusukawa J, Hayabuchi N, et al. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:323–324. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]