Abstract

Although psychological factors are known to affect bladder and bowel control, the occurrence of functional urinary disorders in patients with psychiatric disorders has not been well-studied or described. A higher prevalence of functional lower urinary tract disorders have also been reported amongst patients with obsessive-compulsive (OC) disorders. A systematic literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, OVID Medline, PsycINFO, Clinical Trials Register of the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDANTR), Clinicaltrials.gov and Google Scholar databases found five observational studies on the topic. Unfortunately, as only one study had a (healthy) control group, a meta-analytic approach was not possible. Overall, patients with OC symptoms appeared to have increased occurrence of functional urinary symptoms, e.g., overactive bladder, increase in urgency, frequency, incontinence and enuresis. This was even more common amongst patients with Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) or Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) as opposed to patients with OCD alone. Several biological and behavioural mechanisms and treatment approaches were discussed. However, as the current evidence base was significantly limited and had moderate to serious risk of bias, no strong inferences could be drawn. Further well-designed cohort studies are necessary to better elucidate the observed associations and their management.

Keywords: urinary incontinence, functional, enuresis, obsessive-compulsive, rituals

1. Introduction

Urinary incontinence is a common and often impairing and socially embarrassing occurrence [1]. It is increasingly recognized as a potential symptom in patients with psychiatric disorders [2]. Although psychological factors (including depression and anxiety) are known to affect bladder and bowel control [3], the occurrence of functional urinary disorders in patients with psychiatric disorders has not been well-studied or described.

Functional lower urinary tract disorders comprise a diverse group of disorders, for which there is no apparent neurological disease and the structural aspect remains unknown [4]. They are frequently comorbid in children with attentional and obsessive-compulsive (OC) disorders [5,6,7]. Some case reports have suggested that urination could be a form of compulsion [8,9]; cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has long been applied in the treatment of functional urinary disorders [10]. It has also been hypothesized that these conditions may at least share some common neuropharmacological pathways involving stress-related peptide corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and CRF-related peptides [11], and the treatment of one may improve the other.

It is important for clinicians to promptly recognize and manage these conditions as the experience of incontinence in children and adolescents can perpetuate poor mental health and increase one’s risk of social isolation, bullying and self-esteem issues [12]. However, understanding of the potential Psyche–Soma relationship and its interactions remains underdeveloped.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has been done hitherto to investigate the extent of the association between OC disorders and functional urinary disorders in either adults or children. It was hypothesized that patients with OC symptoms would also have an increased occurrence of functional urinary symptoms. This study aimed to investigate this a priori hypothesis, summarize current evidence and suggest areas for future research.

2. Methods

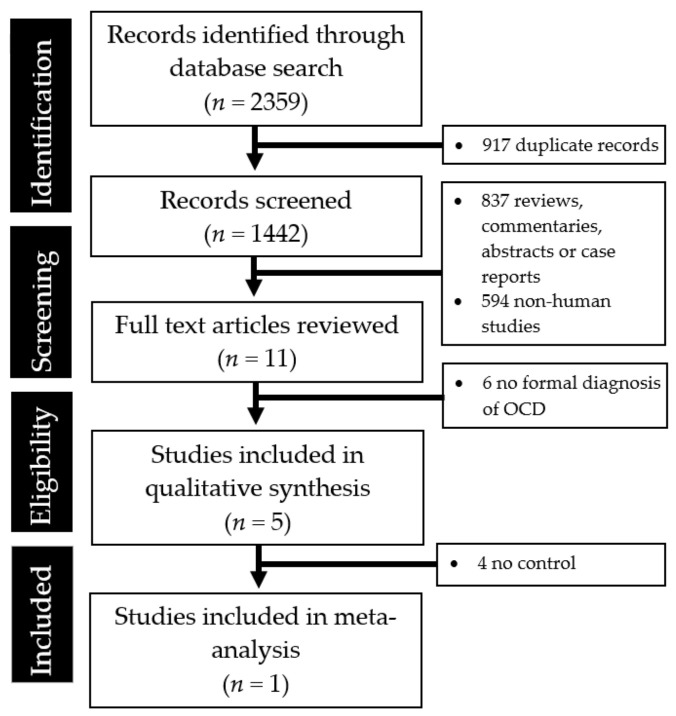

A systematic literature search was performed in accordance with the latest Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. By using the following combinations of broad Major Exploded Subject Headings (MesH) terms or text words [urinary OR incontinence OR enuresis OR overactive OR bladder] AND [obsess * OR compuls * OR OC OR OCD OR yale-brown], a comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, OVID Medline, PsycINFO, Clinical Trials Register of the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDANTR), Clinicaltrials.gov and Google Scholar databases yielded 2359 papers published in English between 1 January 1988 and 1 April 2021. Attempts were made to search grey literature using the Google search engine. Title/abstract screenings were performed independently by three study investigators (Q.X.N., Y.L.L. and W.L.) to identify articles of interest. All retrieved publications were manually reviewed and also checked for references of interest.

The inclusion criteria for this review were: (1) published clinical study, (2) study population with a diagnosis of OCD, and (3) reported occurrence or prevalence of functional urinary disorders (e.g., overactive bladder, functional urinary incontinence, etc.). Any disagreement on inclusion was resolved by consensus. Exclusion criteria included case reports, case series, conference abstracts and proceedings, which were not accepted for this systematic review.

Data were extracted using a standardized electronic form by one study investigator (Q.X.N.) and cross-checked by a second investigator (Y.L.L.) for accuracy. The quality and risk of bias of the studies were also assessed with the ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions) tool [14], graded based on consensus of three study investigators (Q.X.N., Y.L.L. and W.L.).

3. Results

The abstraction process (and reasons for exclusion) is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the studies identified during the literature search and abstraction process.

A total of five observational studies were systematically reviewed. The details of the studies, including the study demographics, are summarized in Table 1. Unfortunately, as only one study had a (healthy) control group, a meta-analytic approach was not possible. For the same reasons, a sensitivity analysis was not performed.

Table 1.

Clinical studies reporting the occurrence of functional urinary disorders in patients with OC symptoms.

| Author, Year | Country of Origin | Study Design and Study Population | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2016 [15] | Korea | Case-control; n = 114 (57 women with OAB and 57 healthy female controls); Average age 50.65 ± 14.72 years |

|

| Arlen et al., 2014 [16] | United States | Retrospective chart review; n = 20 (2 boys and 18 girls); Average age 6.9 (range: 4 to 12 years) |

|

| Bernstein et al., 2010 [17] | United States | Case-control; n = 39 (24 boys and 15 girls); Average age 10.66 years |

|

| Jaspers-Fayer et al., 2017 [18] | Canada | Prospective cohort; n = 136 (54% males); Age range 6 to 19 years |

|

| Murphy & Pichichero, 2002 [19] | United States | Prospective case identification and followup; n = 12 (7 boys and 5 girls); Average age 5 years (range: 5 years 4 months to 10 years 11 months) |

|

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; OAB, overactive bladder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratio; PANDAS, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections; PANS, pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome; UTI, urinary tract infection.

In terms of the quality of the available studies, most were observational in nature, had relatively small sample sizes and overall moderate to serious risk of bias, due to the lack of control for potential confounding factors and selection bias, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment with ROBINS-I tool.

| Study | Confounding | Selection | Measurement of Intervention | Missing Data | Measurement of Outcomes | Reported Result | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2016 [15] | Serious | Serious | N/A | ? | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Arlen et al., 2014 [16] | Serious | Serious | N/A | ? | Serious | Serious | Serious |

| Bernstein et al., 2010 [17] | Serious | Serious | N/A | ? | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Jaspers-Fayer et al., 2017 [18] | Moderate | Serious | N/A | ? | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Murphy & Pichichero, 2002 [19] | Serious | Serious | N/A | Moderate | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

Abbreviations: ?, insufficient information to determine risk of bias; N/A, not applicable.

4. Discussion

Overall, patients with OC symptoms appeared to have increased occurrence of functional urinary symptoms, e.g., an increase in urgency, frequency, incontinence and enuresis. This appeared to be even more common amongst patients with PANDAS/PANS as opposed to patients with OCD alone [17,18,19].

There are many causes of urinary incontinence and they can be broadly classified as stress incontinence (related to weakness of the pelvic floor support and increases in intraabdominal pressure), urge incontinence (believed to be due to detrusor overactivity), overflow incontinence, mixed incontinence, or functional incontinence (thought to be caused by non-genitourinary factors, such as cognitive or physical impairments, affecting one’s ability to void independently) [20]. Psychogenic polydipsia is more common in patients with schizophrenia than patients with OCD [21]. It is thought that some patients with OCD may have delayed voiding of the bladder because of certain contamination fears or OC rituals, resulting in functional incontinence. To remedy this, adherence to a strict bowel program and timed voiding regimen may be helpful [16]. Clinicians may schedule for them to urinate every two to four hours.

There is also a proposed subtype of OCD patients who have urinary obsessions and they may report predominant fear of urinary incontinence and urinary frequency without organic etiology [22]. These patients appear to respond to antidepressants. The treatment of OCD may be very complex and refractory in some cases and could require add-on atypical antipsychotic medication and psychotherapies [23].

Another potential contributory factor include the psychotropic medications themselves. The lower urinary tract is influenced by various neurotransmitter pathways. In literature, there have been several case reports of urinary incontinence associated with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants [24] and antipsychotics over a broad range of doses [25]. In terms of biological mechanisms, SSRIs may have agonist effects on 5-HT4 receptors, which are also found in the urinary tract and could evoke responses in the bladder and urethra [26]. In isolated detrusor muscle strips from guinea pigs, 5-HT4 receptors were found to potentiate purinergic transmission and thus initiate the voiding reflex [27]. A retrospective chart analysis of 13,531 first-time users of an SSRI also found that the adjusted relative risk of urinary incontinence with SSRI exposure (compared to non-exposure) was 1.61 (with a 95% confidence interval of 1.42 to 1.82) [28]. This risk was higher amongst females, the elderly and patients prescribed sertraline compared to the other SSRI antidepressants. As for both typical and atypical antipsychotics, they may affect detrusor overactivity and reduce bladder compliance [29]. However, the mechanisms remain unclear and individual susceptibility may differ.

In addition to the serotonergic and antipsychotic drugs, clomipramine could also induce urinary symptoms in patients with OCD [30], as can happen with benzodiazepines and other drugs [31].

Unfortunately, the current evidence base was significantly limited and a meta-analytic approach was not possible. The studies were also observational in nature, had relatively small sample sizes and overall moderate to serious risk of bias. This also meant that we were unable to prove causation and the observations could indeed be fortuitous. There was also the possibility of ascertainment bias with case collection studies. The conclusions must thus be interpreted in light of these shortcomings.

Further well-designed cohort studies on the subject are necessary to clarify these observed associations and their management.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our systematic review found five observational studies, which all showed increased occurrence of functional urinary symptoms in patients with OC symptoms. In clinical practice, it is known that patients with OCD may manifest with various symptoms, however, it remains unclear if the observed functional urinary symptoms are fortuitous, biological or even behavioral in nature. Nonetheless, as urinary incontinence can be particularly distressing and socially embarrassing for the individual, this should be sensitively elicited in the clinical history and approach to these patients. The importance of a good history and a holistic understanding of the patient’s psychiatric phenomenology cannot be overstated. There are still significant gaps in our present understanding of this Psyche–Soma relationship, which could be the result of biological feedback, medications or other neural pathways. Further well-designed cohort studies on the subject would help shed light on these associations and their management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X.N. and K.T.C.; methodology, Q.X.N., Y.L.L., W.L. and W.S.Y.; formal analysis, Q.X.N., Y.L.L., W.L., W.S.Y. and K.T.C.; investigation, Q.X.N., Y.L.L., W.L., W.S.Y. and K.T.C.; resources, Q.X.N., W.L. and K.T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.X.N., Y.L.L., W.L., W.S.Y. and K.T.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.X.N., Y.L.L., W.L., W.S.Y. and K.T.C.; supervision, W.S.Y. and K.T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Elenskaia K., Haidvogel K., Heidinger C., Doerfler D., Umek W., Hanzal E. The greatest taboo: Urinary incontinence as a source of shame and embarrassment. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2011;123:607–610. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-0013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalhais A., Araújo J., Jorge R.N., Bø K. Urinary incontinence and disordered eating in female elite athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2019;22:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasudev K., Gupta A.K. Incontinence and mood disorder: Is there an association? Case Rep. 2010;2010:bcr0720092118. doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2009.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leue C., Kruimel J., Vrijens D., Masclee A., Van Os J., Van Koeveringe G. Functional urological disorders: A sensitized defence response in the bladder–gut–brain axis. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017;14:153–163. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Gontard A., Hollmann E. Comorbidity of functional urinary incontinence and encopresis: Somatic and behavioral associations. J. Urol. 2004;171:2644–2647. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000113228.80583.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang T.K., Huang K.H., Chen S.C., Chang H.C., Yang H.J., Guo Y.J. Correlation between clinical manifestations of nocturnal enuresis and attentional performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2013;112:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulisano M., Domini C., Capelli M., Pellico A., Rizzo R. Importance of neuropsychiatric evaluation in children with primary monosymptomatic enuresis. J. Pediatric Urol. 2017;13:36.e1–36.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiwanmall S.A., Kattula D. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Presenting with Compulsions to Urinate Frequently. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2016;38:364–365. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.185953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahmat R. Urinary frequency: Going beyond the tract. Malays Fam. Physician. 2020;15:58–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowrer O.H., Mowrer W.M. Enuresis—A method for its study and treatment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1938;8:436–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1938.tb06395.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seki M., Zha X.M., Inamura S., Taga M., Matsuta Y., Aoki Y., Ito H., Yokoyama O. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor on bladder function in rats with psychological stress. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9828. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda H., Oyake C., Oonuki Y., Fuyama M., Watanabe T., Kyoda T., Tamura S. Complete resolution of urinary incontinence with treatment improved the health-related quality of life of children with functional daytime urinary incontinence: A prospective study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020;18:14. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-1270-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne J.A., Hernán M.A., Reeves B.C., Savović J., Berkman N.D., Viswanathan M., Higgins J.P. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn K.S., Hong H.P., Kweon H.J., Ahn A.L., Oh E.J., Choi J.K., Cho D.Y. Correlation between overactive bladder syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder in women. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2016;37:25–30. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2016.37.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arlen A.M., Dewhurst L.L., Kirsch S.S., Dingle A.D., Scherz H.C., Kirsch A.J. Phantom urinary incontinence in children with bladder-bowel dysfunction. Urology. 2014;84:685–688. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein G.A., Victor A.M., Pipal A.J., Williams K.A. Comparison of clinical characteristics of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections and childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2010;20:333–340. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaspers-Fayer F., Han SH J., Chan E., McKenney K., Simpson A., Boyle A., Stewart S.E. Prevalence of acute-onset subtypes in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:332–341. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy M.L., Pichichero M.E. Prospective identification and treatment of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with group A streptococcal infection (PANDAS) Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2002;156:356–361. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holroyd-Leduc J.M., Tannenbaum C., Thorpe K.E., Straus S.E. What type of urinary incontinence does this woman have? JAMA. 2008;299:1446–1456. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oades R.D., Daniels R. Subclinical polydipsia and polyuria in young patients with schizophrenia or obsessive-compulsive disorder vs normal controls. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;23:1329–1344. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(99)00069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein S., Jenike M.A. Disabling urinary obsessions: An uncommon variant of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:450–452. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(90)72143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Casale A., Sorice S., Padovano A., Simmaco M., Ferracuti S., Lamis D.A., Rapinesi C., Sani G., Girardi P., Kotzalidis G.D., et al. Psychopharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019;17:710–736. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180813155017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maalouf F.T., Gilbert A.R. Sertraline-Induced enuresis in a prepubertal child resolves after switching to fluoxetine. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2010;20:161–162. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes T.R., Drake M.J., Paton C. Nocturnal enuresis with antipsychotic medication. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2012;200:7–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bockaert J., Claeysen S., Compan V., Dumuis A. 5-HT4 receptors: History, molecular pharmacology and brain functions. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:922–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messori E., Rizzi C.A., Candura S.M., Lucchelli A., Balestra B., Tonini M. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors that facilitate excitatory neuromuscular transmission in the guinea-pig isolated detrusor muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:677–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Movig K.L.L., Leufkens H.G.M., Belitser S.V., Lenderink A.W., Egberts A.C.G. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced urinary incontinence. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2002;11:271–279. doi: 10.1002/pds.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torre D.L., Isgrò S., Muscatello M.R.A., Magno C., Melloni D., Meduri M. Urinary incontinence in schizophrenic patients treated with atypical antipsychotics: Urodynamic findings and therapeutic perspectives. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2005;9:116–119. doi: 10.1080/13651500510018329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermesh H., Aizenberg D., Weizman A., Lapidot M., Munitz H., Rivera G.C., Dion P. Clomipramine-induced urinary dysfunction in an obsessive-compulsive adolescent. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1987;21:877–879. doi: 10.1177/106002808702101105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhamme K.M., Sturkenboom M.C., Stricker B.H.C., Bosch R. Drug-induced urinary retention. Drug Saf. 2008;31:373–388. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.