Abstract

Peripheral nerve injuries remain challenging to treat despite extensive research on reparative processes at the injury site. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of immune cells, particularly macrophages, in recovery from nerve injury. Macrophage plasticity enables numerous functions at the injury site. At early time points, macrophages perform inflammatory functions, but at later time points, they adopt pro-regenerative phenotypes to support nerve regeneration. Research has largely been limited, however, to the injury site. The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), the synapse between the nerve terminal and end target muscle, has received comparatively less attention, despite the importance of NMJ reinnervation for motor recovery. Macrophages are present at the NMJ following nerve injury. Moreover, in denervating diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), macrophages may also play beneficial roles at the NMJ. Evidence of positive macrophages roles at the injury site after peripheral nerve injury and at the NMJ in denervating pathologies suggest that macrophages may promote NMJ reinnervation. In this review, we discuss the intersection of nerve injury and immunity, with a focus on macrophages.

Keywords: nerve injury, nerve regeneration, macrophage, neuromuscular junction, glial cells

Introduction

Insults to the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are common and can be debilitating. Over 2% of patients with limb trauma suffer peripheral nerve injuries [1]. These injuries often have long term detrimental effects on quality of life, with 30% of patients with work-related nerve injuries suffering permanent disabilities [2, 3]. Nerve-related injuries also have a high financial burden. Traumatic injuries to the brachial plexus, for example, are estimated to incur over $1.1 million in indirect costs per patient [4]. Degenerative neuromuscular diseases, while rarer, have devastating effects on the PNS. Neuromuscular diseases can cause temporary or permanent paralysis, which can be life-threatening. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), for example, affects approximately 5 in 100,000 people in the United States [5] and is characterized by an ultimately fatal progressive paralysis, with only 7% of patients surviving 5 years after diagnosis [6]. Understanding the processes underlying PNS damage—from either traumatic or neurodegenerative etiologies—and optimizing repair is critical to reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with peripheral nerve injuries and neuromuscular diseases.

The body’s response to PNS nerve damage involves multiple cell types, including axonal Schwann cells (SCs), terminal (perisynaptic) Schwann cells (tSCs), endothelial cells, and immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and T-cells. tSCs are non-myelinating glial cells that reside at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) and perform a wide variety of roles, including maintaining NMJ structure [7], phagocytosing nerve debris after injury [8], and facilitating endplate reinnervation [9, 10]. Endothelial cells associated with blood vessels increase in number with angiogenesis and guide myelinating SCs, which then guide regenerating axons, across a nerve injury site [11]. Immune cells mount inflammatory responses to PNS insults and perform a variety of other roles, including clearing cellular debris and secreting factors integral to regeneration, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key regulator of angiogenesis [12].

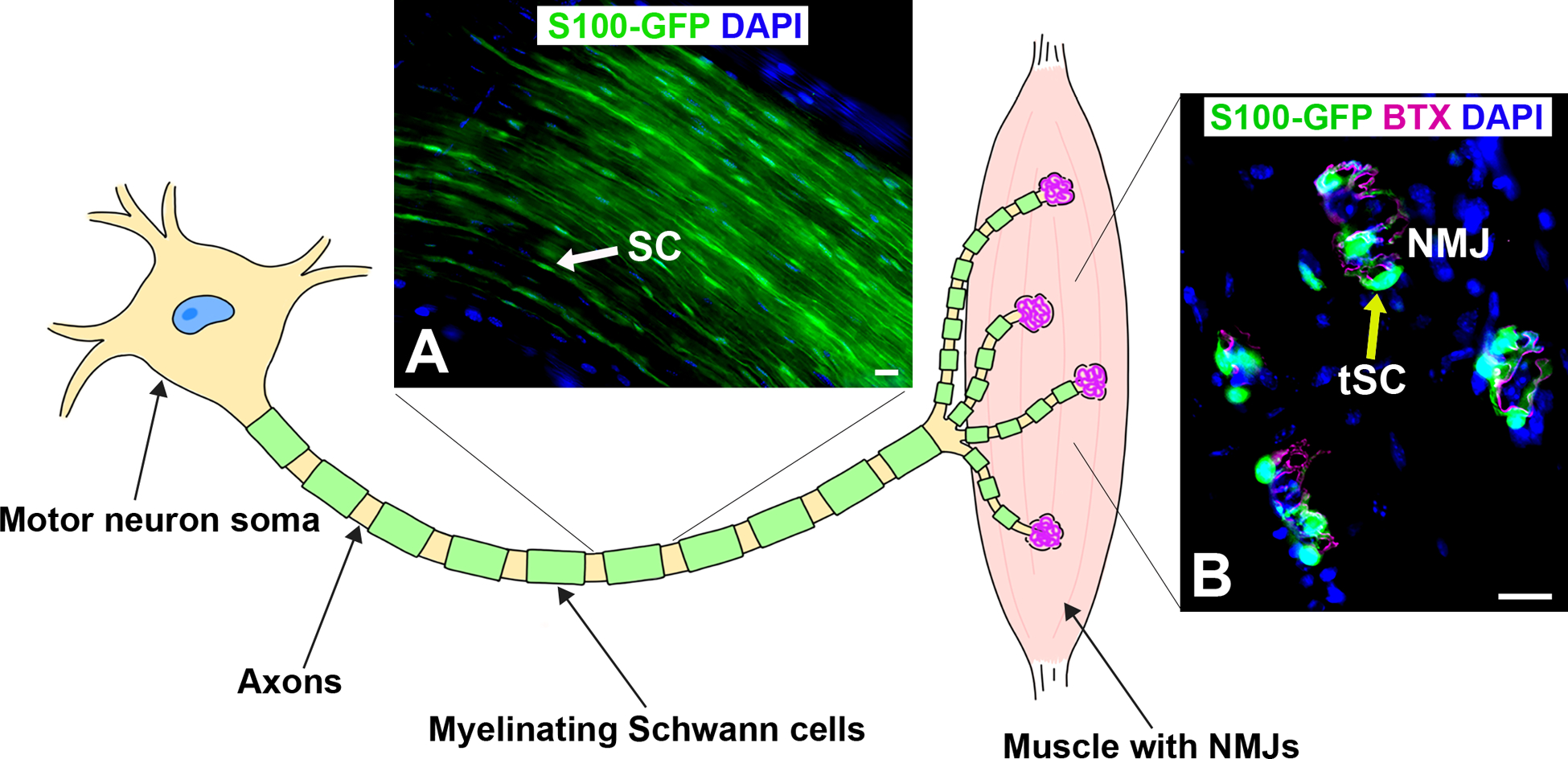

Peripheral nerve damage ultimately disrupts the NMJ, causing functional muscle denervation. The NMJ is where an axon terminal contacts a motor endplate (Figure 1) and is critical for muscle function. The axon terminal releases acetylcholine, which binds to receptors on the motor endplate to cause muscle contraction [13, 14]. Mechanisms of denervation and reinnervation at the level of the synapse have been understudied; however, they are critically important. When a nerve is damaged, the distal segment of the axon beyond the injury degenerates, and the nerve endings that once innervated NMJs are lost. If axons grow across the injury site but do not properly reinnervate NMJs, motor improvement will be limited. NMJ reinnervation is vital for regaining muscle function. Additionally, functional recovery is positively correlated with completely reinnervated NMJs [15]. NMJ disturbances are central to the development of neuromuscular diseases as well. ALS [16], spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [17], and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) [18] can all result in denervation at the level of the NMJ. In ALS rodent models, therapies that rescue lower motor neurons but fail to protect NMJs do not improve lifespan [19]; reviewed in [20]. It is clear that treatment and research strategies focused only at the motor neuron or axonal regeneration are incomplete; understanding degenerative and regenerative processes at the NMJ is vital to improving recovery after injury and disease.

Figure 1. Illustration of motor neuron and the end target muscle with neuromuscular junctions (NMJs).

A) Representative image of myelinating Schwann cells (SC, green, arrow) along the axons within the sciatic nerve in young adult S100-GFP mice. B) Representative image of longitudinal section of extensor digitorum longus muscle with neuromuscular junctions containing non-myelinating terminal SCs (tSC, green, yellow arrow) overlaying acetylcholine receptors (BTX, magenta). S100-GFP = glial cells (green), BTX = α‐bungarotoxin, DAPI = nuclear staining (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. N = 4 mice.

The immune response is important for axonal regeneration at the nerve injury site and also occurs downstream in the muscle, where is integral to NMJ reinnervation. Changes in monocyte/macrophage activity at the NMJ have been observed after PNS insults, including peripheral nerve injuries [21], ALS [22, 23], and SMA [24]. Macrophages are an incredibly diverse cell type; they can both stimulate and control inflammation and they have the capacity to promote nerve repair. They are known to phagocytose debris of necrotic tissue fragments [25], secrete growth factors [26, 27], promote angiogenesis [11], and interact with tSCs and immune cells [12, 28]. Unfortunately, their role at the NMJ in peripheral nerve injury has received less investigative focus. While nerve injuries are distinct from other PNS insults like ALS, SMA, and GBS, all of these pathologies ultimately converge on the functional denervation of the NMJ and consequent paralysis. Evaluating macrophage roles at the NMJ in multiple types of PNS damage provides a more complete picture of macrophage activity in the PNS and may yield insights as to their activity in nerve injuries. In this review, we discuss macrophage roles in PNS pathologies with a focus on the NMJ.

Macrophage Types and Function

Classifying macrophage phenotypes allows us to predict their behavior, relate their activity to other pathologies, and potentially influence their activity. Macrophages come in two classes, tissue-resident and infiltrating [29]. Tissue-resident macrophages are present in peripheral nerves under homeostatic conditions, and can proliferate following injury or infection. Monocytes, which differentiate into macrophages, circulate in the blood and infiltrate damaged tissues. It is theorized that these two kinds of macrophages play distinct roles in recovery from nerve injury. There are two distinct types of resident macrophages in sciatic nerve, epineurial and endoneurial macrophages, which have distinct transcriptomes and respond differently to nerve injury [30]. Endoneurial resident macrophages produce chemoattractants for monocytes and other leukocytes to the injured nerve, while epineurial macrophages do not significantly alter their transcriptomes post-injury [30]. Infiltrating macrophages produce more cytokines, such as CCL2 and CCL3, which further enhance macrophage recruitment [31]. After the injury is healed, infiltrating macrophages adopt the signature transcriptome of peripheral nerve resident macrophages and remain in the nerve [30].

Macrophage functional phenotypes are traditionally categorized as either M1 (classically activated) or M2 (alternatively activated) [26, 32]; reviewed in [33, 34]. Different macrophage phenotypes have distinct expression profiles of cytokines, chemokines, receptors, and various enzymes. M1 macrophages are considered pro-inflammatory, because they produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [35, 36]. M2 macrophages are anti-inflammatory and produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, for example, IL-10 and TGFβ [35, 36]. For this reason, M1 macrophages are often considered “bad” while M2 macrophages are “good”. However, the roles of M1 and M2 macrophages are more nuanced than this dichotomy suggests, and in reality, their phenotypes are flexible and exist on a spectrum [37, 38]. Pro-inflammatory macrophages can even convert to anti-inflammatory phenotypes, underscoring their remarkable plasticity [39]. Macrophages change their gene and protein expression in response to the local microenvironment. Many molecules affect macrophage polarization, including cytokines, fatty acids, extracellular matrix components, and numerous other factors [40]. The huge number of molecules that can influence macrophage polarization makes defining M1 and M2 macrophages in vivo quite difficult. In vitro, IFN-γ, LPS, and TNF-α can prompt a macrophage to change its gene and protein expression to become an M1 macrophage, whereas IL-4 and IL-13 can polarize a macrophage to an M2 phenotype [36].

Macrophages After Nerve Injury

Macrophages have been well-studied at the nerve injury site and are vital to nerve regeneration [11, 41, 42]; reviewed in [43, 44]. After nerve transection, the distal nerve segment rapidly degenerates in a process called Wallerian degeneration. Endoneurial macrophages express CCL7, which attracts both M1 and M2 macrophages to the injury site [30, 45]. Infiltrating macrophages invade the injury site and distal nerve segment, ultimately outnumbering resident macrophages 3:1 [46]. More recent studies have suggested that up to 90% of macrophages observed in the sciatic nerve after injury are derived from infiltrating monocytes [30]. The predominant phenotype in the first few days is the M1 phenotype, which declines after 3 to 5 days as the M2 phenotype increases [26, 47, 48]. By two weeks, the accumulated macrophages express intermediate phenotypes and a mixture of M1 and M2 markers [26, 47]. The temporal specificity and differential cytokine expression of M1 and M2 macrophages suggests that they likely play distinct roles in recovery from nerve injury. Thus, influencing these phenotypes can affect regeneration. M1 macrophages are believed to be important for phagocytosis during early Wallerian degeneration. Injection of LPS, a stimulus for M1 polarization, into an injured nerve promotes macrophage accumulation, phagocytosis, and recovery [49]. Conversely, ablation of TLR4, which binds LPS, impairs macrophage recruitment, Wallerian degeneration, and recovery [50]. M1 macrophages also produce more VEGF, a pro-angiogenesis growth factor, than M2 macrophages [26]. This suggests a beneficial role for M1 macrophages, despite their “negative” pro-inflammatory reputation. M2 macrophages are important for regeneration, consistent with their anti-inflammatory characterization. Deficiency of IL-10, an M2 inducer, delays the switch from the M1 to the M2 phenotype, causing prolonged expression of inflammatory cytokines and impaired functional recovery [51]. Alternatively, increasing M2 polarization has a beneficial effect on nerve recovery [52]. In addition, the ratio of pro-healing (M2a and M2c subtypes) to pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages three weeks after scaffold or autograft nerve repair is directly correlated with regenerative outcomes [53]. Thus, there is a delicate balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages during different phases of nerve regeneration.

Nerve regeneration can also be affected by changes in the number of macrophages recruited, in addition to their phenotypes. After injury, SCs express CCL2 (also called monocyte chemoattractive protein-1 or MCP-1), which attracts macrophages to the damaged nerve [54, 55]. Consequently, a deficiency of the CCL2 receptor, CCR2, reduces macrophage infiltration resulting in decreased myelin phagocytosis [56]. Axon regeneration across acellular nerve allografts, a bridging material used to repair nerve defects, has recently been investigated in Ccl2 knockout mice [57]. These mice exhibited impaired macrophage recruitment, leading to delayed angiogenesis and nerve regeneration. They ultimately had reduced functional recovery compared to wild-type mice, underscoring the importance of infiltrating macrophages in nerve injury [57]. Others have observed changes in macrophage activity in mice lacking the Vav gene, a cytoskeleton transcription factor. Vav knockout mice exhibited slower macrophage recruitment and activation at the injury site [58]. These mice had impaired revascularization, decreased NMJ reinnervation, delayed functional recovery, and ultimately impaired motor function, further highlighting the importance of macrophages in reinnervation. Interestingly, there is evidence suggesting that sufficient myelin clearance occurs after axotomy even in the absence of infiltrating macrophages. Ccr2 knockout mice exhibit efficient Wallerian degeneration even though they have reduced macrophage recruitment following axotomy [59, 60]. It has been shown that neutrophils can compensate for a lack of CCR2+ macrophages [59]. Depleting macrophages clearly has deleterious effects, but those effects may be unrelated to myelin phagocytosis or may occur outside the injury site.

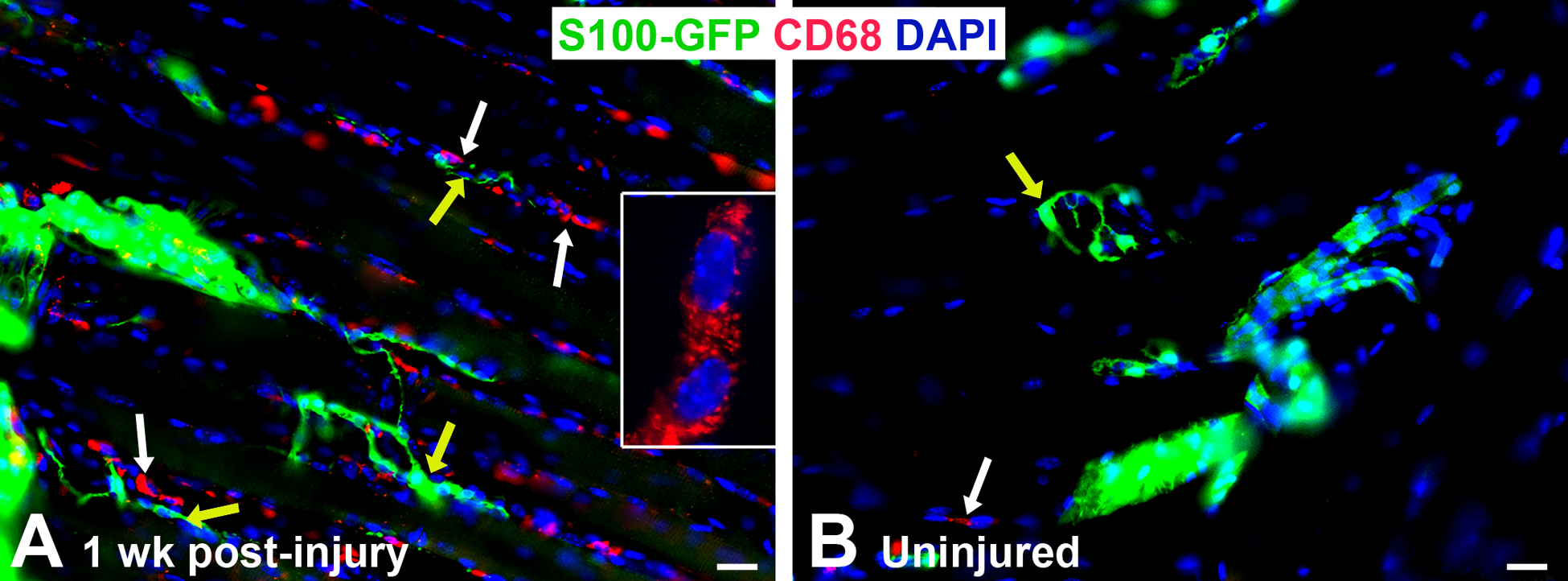

Alterations in macrophage number or phenotype may affect other cell types important for nerve regeneration, for example, SCs and endothelial cells. Macrophages are also known to influence the activity of SCs at the injury site through the secretion of trophic factors [61]. They promote neural growth factor expression by SCs and promote SC migration, proliferation, and maturation [53, 62–64]. Macrophages also play a crucial role in angiogenesis and subsequent reinnervation [11]. All monocytes that infiltrate the nerve after nerve injury express VEGF, emphasizing its importance in reinnervation [30]. Macrophages secrete VEGF in response to the hypoxic environment at the injury site, which promotes the formation of polarized blood vessels. SCs then use these blood vessels as tracks to cross the gap between the cut ends of the nerve, guiding a pathway for axonal regeneration [11]. In other tissue types, macrophages that overexpress VEGF or pleiotrophin can transdifferentiate into functional endothelial cells and incorporate into blood vessels [65, 66]. Hypoxia can also prompt macrophages to express endothelial markers and form vessel-like networks connected to the systemic vasculature [67]. Further investigation is required to determine if this novel function of macrophages plays a role in recovery after nerve injury. Taken together, current evidence suggests that macrophage regenerative roles in the PNS extend far beyond phagocytosis. In addition, their activity is not limited to the injury site. Recent studies have demonstrated macrophage infiltration at the NMJ following nerve injury (Figure 2) [12, 21]. These data support the need to evaluate for other potential macrophage roles at the NMJ.

Figure 2. Macrophages are present in the extensor digitorum longus muscle after nerve injury in young adult S100-GFP mice.

A) Representative image of immunofluorescence staining showing increased CD68+ macrophages/image area (red, white arrows) around the NMJ (yellow arrows) one week (wk) following sciatic nerve transection and immediate repair, while uninjured (control) mice (B) have nearly no macrophages present (white arrow). Yellow arrow indicates NMJ with tSCs. Anti-CD68 rat Ab (#MCA1957, BioRad) = macrophages (red), S100-GFP = glial cells (green), DAPI = nuclear staining (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. N = 4 mice/time point.

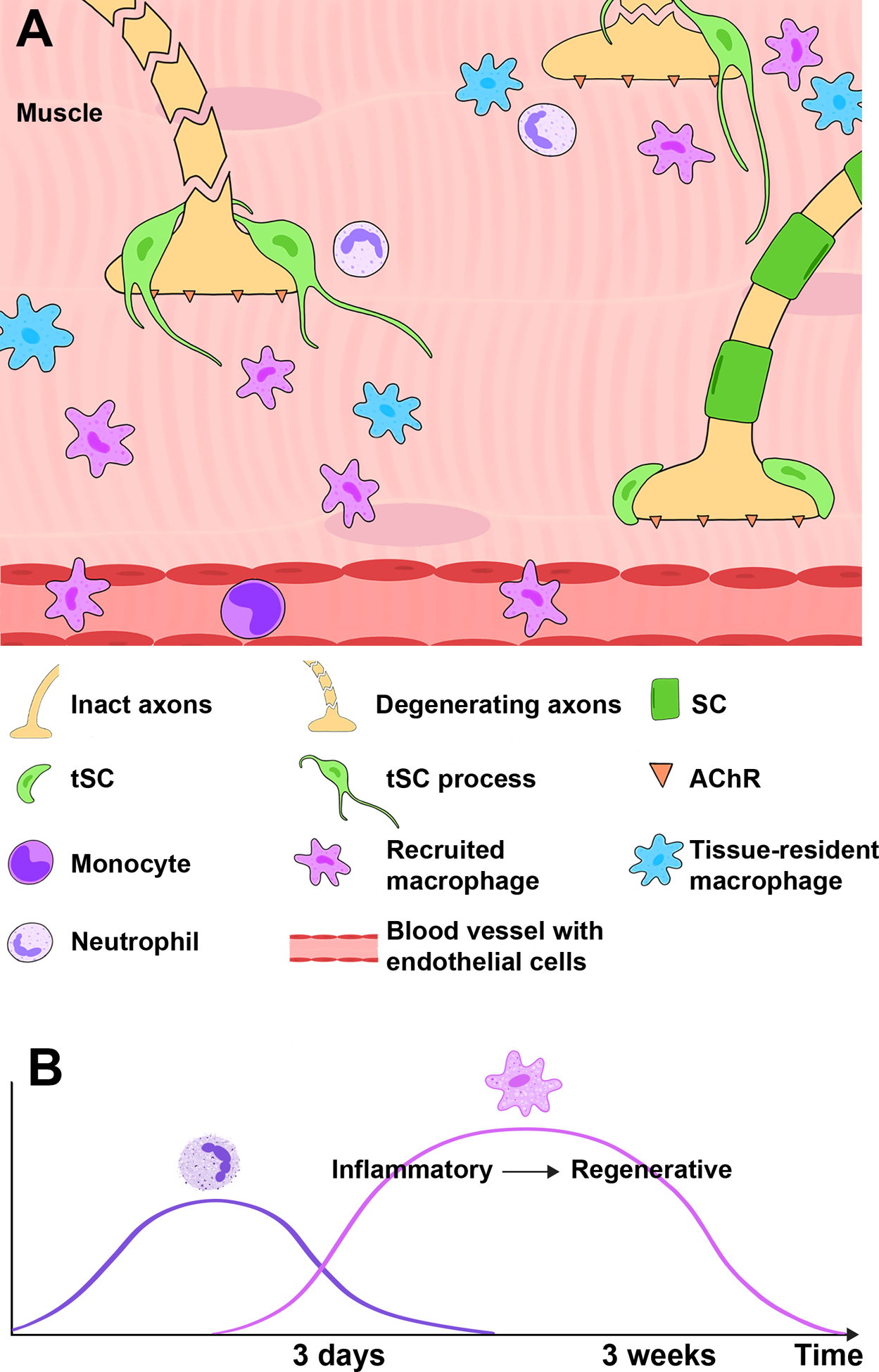

Many of the NMJ studies related to nerve injury focus on tSCs, which play critical roles in NMJ reinnervation [9, 10]; reviewed in [68]. Beginning three days after nerve injury, tSCs at denervated synapses extend their processes to nearby NMJs with intact innervation [12, 69, 70] (Figure 3). These processes serve as a guide for intact nerves to reach denervated synapses. tSCs also acquire phagocytic activity following nerve injury, clearing nerve terminal debris that would otherwise impede axon regrowth and NMJ reinnervation [8, 71]. In addition, they possibly attract immune cells to the NMJ. tSCs produce CXCL12a, a chemotactic molecule that attracts lymphocytes and binds to the CXCR4 receptor. Blocking CXCL12a delays NMJ reinnervation, highlighting the importance of immune cells to NMJ recovery [72]. More specifically, tSCs recruit macrophages to the NMJ, which reach peak density 1 week after nerve injury [21]. Macrophages work in concert with tSCs to support reinnervation by phagocytosing debris [8]. The interplay between macrophages and SCs has been demonstrated in recent experiments with cGpr126 mice, which lack the adhesion G-protein coupled receptor Gpr126 in SCs [21, 73]. These mice have diminished NMJ reinnervation and muscle weight after nerve injury and repair [21, 73]. cGpr126 mice exhibit decreased macrophage infiltration at the injury site and at the NMJ, reflecting impaired recruitment of macrophages by SCs and tSCs [21, 73]. Cytokine mRNA expression at the NMJ is altered as well, with decreased Tnf-a, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, and increased IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine [21]. Interestingly, Vegfa expression at the NMJ is reduced in cGpr126 mice [21]. This may be a consequence of reduced macrophage infiltration. Elevated Vegfa mRNA expression coincides with the onset of macrophage infiltration 3 days after nerve injury and repair [12]. Conditionally knocking out Vegfa in macrophages has detrimental effects at the NMJ, decreasing NMJ reinnervation and functional recovery [12]. Interactions between tSCs and macrophages may influence tSC process extension as well. cGpr126 mice and Vegfa conditional knockout mice both exhibit impaired tSC process extension [12, 21]. These data suggest that coordinated activity of tSCs and macrophages is essential to recovery from nerve injuries at the level of the NMJ. Therefore, macrophages likely have other functions at the NMJ in addition to their traditional phagocytic role.

Figure 3. Diagram showing tSC injury response and the cellular immune response at the NMJ in the muscle after nerve injury.

A) After nerve cut and repair, tissue-resident macrophages and recruited neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages surround NMJs and promote NMJ reinnervation. In addition, tSCs at denervated synapses extend their processes to nearby NMJs with intact innervation. These processes serve as a guide for intact nerves to reach denervated NMJs, promoting reinnervation. B) Neutrophils are early responders, while macrophage infiltration increases at 3 days after injury. Over several weeks, macrophages progress from inflammatory to regenerative phenotypes.

Macrophages’ high degree of plasticity allows them to perform multiple, contrasting roles in nerve injury. At the nerve injury site, they promote angiogenesis and regeneration. Current evidence suggests that macrophages may play similar roles at the NMJ, but the macrophage phenotypes active at NMJs and their functional contributions to reinnervation remain to be determined. Investigation of the diverse macrophage phenotypes and their dynamic regulation by the microenvironment at the NMJ during different stages of nerve injury and repair is integral to enhancing recovery of the end target muscle.

Macrophages and NMJ Disease

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease that causes progressive paralysis as upper and lower motor neurons die. The NMJ is pivotal in the development of ALS. Denervation at the level of the NMJ precedes motor neuron loss and symptom development and worsens as symptoms progress [16, 22]. The role of macrophages in ALS progression is complex; they seem to be protective in early stages and degenerative in later stages. Enlarged macrophages are seen in peripheral nerves of Sod1G93A mice, an ALS mouse model, before symptom onset, and activated macrophages are seen throughout the PNS after symptom onset [74, 75]. The majority of activated macrophages are infiltrating macrophages [74]. As symptoms progress, macrophages expressing CD11b increase in muscle, particularly surrounding NMJs [22, 23]. Severely affected muscles exhibited greater macrophage infiltration than less affected muscles [74]. Despite the dramatic infiltration of macrophages in the peripheral nerves and muscles of Sod1G93A mice, the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 are not elevated [74]. This finding suggests that the widespread immune activation observed in the peripheral nervous system is not necessarily harmful. The roles of macrophages in the pathogenesis of ALS are highlighted in fast- and slow-progressing strains of Sod1G93A mice. The fast-progressing strain exhibits more extensive denervation at symptom onset than the slow-progressing strain [76]. The slow-progressing strain exhibits greater immune activation, including upregulation of CCL2 and complement C3, which recruit macrophages from the blood [76]. Despite increased macrophage activity in the slow-progressing strain, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF and Ly6c are not elevated in peripheral nerves, consistent with previous findings [74, 76]. Rather, these macrophages may perform anti-inflammatory roles. Ym1, an M2 marker, is elevated in the slow-progressing strain compared to wild-type mice [76]. Reciprocal activation between regulatory T cells (Treg) and M2 macrophages seems to slow disease progression. Treg cells that express CD4, CD25, and FOXP3 can polarize macrophages to M2 phenotypes, which in turn can induce Tregs [28, 77, 78]. In human ALS patients, greater numbers of Tregs and increased FOXP3 expression is associated with slower disease progression [79]. Monocytes from slow-progressing patients express fewer pro-inflammatory genes than those of fast-progressing patients, suggesting a predominance of anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes [80]. In summary, these findings demonstrate that greater macrophage activity, particularly anti-inflammatory M2-like activity, is associated with slower disease progression. Nardo et al. hypothesized that macrophages, SCs, and CD8+ T-cells work together to destroy defective nerve fibers and eliminate axon growth inhibitors, promoting the de-differentiation and proliferation of SCs in order to create a hospitable environment for new neurites to grow [76]. In addition to this phagocytic role, macrophages appear to have an immunomodulatory role in conjunction with Tregs [78–80].

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neuromuscular disorder caused by mutations in the Survival Motor Neuron gene. It is characterized by lower motor neuron loss, significant muscle denervation, and, eventually, paralysis. NMJ changes are central to SMA pathology [17, 81, 82]. Mouse models of SMA exhibit significant degenerative changes at the NMJ prior to exhibiting clinical signs of disease [83]. Unsurprisingly, increasing degrees of NMJ disruption correlate with disease severity [24, 83]. It has been demonstrated that SMA model mice progressively lose innervation at the level of the NMJ [17, 84]. In addition, macrophages are depleted in the muscle over time in SMA model mice as their disease becomes more severe [24]. Newborn SMA and wild-type mice have similar macrophage densities in muscle, but by postnatal day 6, SMA mice have fewer macrophages than healthy controls [24]. Macrophage loss, then, appears to be detrimental. This benefit could result from loss of macrophage anti-inflammatory activity or accumulation of cellular debris in the absence of adequate phagocytosis.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute flaccid paralysis that typically occurs following a viral or bacterial infection, such as Campylobacter jejuni [85]. Variable nerve degeneration and demyelination in GBS is initiated by autoantibodies that target nerve epitopes, such as gangliosides [86–88]. Several GBS-associated autoantibodies target epitopes present at the NMJ and can disrupt synaptic transmission [18, 89, 90]. It is believed that macrophages mediate much of the axonal damage and demyelination seen in GBS [91, 92]. Macrophages have been observed invading axons in GBS models, particularly near nodes of Ranvier [91, 93, 94]. In the experimental autoimmune neuritis mouse model of GBS, SCs express CCL2 and recruit CCR2+ macrophages, which may mediate inflammation and demyelination [95]. Human patients with GBS have high serum CCL2 levels, with the highest levels seen in the most severely disabled patients [96]. This suggests that increased macrophage recruitment worsens GBS symptoms. In other models, however, macrophage invasion of the nerve is most strongly associated with the early recovery phase, suggesting they may play a positive role, perhaps resolving inflammatory processes that damaged the nerve [97]. Macrophages appear to have dual roles in GBS, contributing to both damage and repair [98]. Their role may differ in various animal models and subtypes of GBS. Influencing macrophage polarization is a promising avenue for future GBS therapies. Recent studies in the experimental autoimmune neuritis model of GBS demonstrate that polarization to an M2 phenotype decreases disease severity and promotes recovery [99–101].

Unlike ALS and SMA, most patients recover from GBS. Thus, similar to traumatic nerve injury, axon regeneration and NMJ reinnervation are crucial. Autoantibodies associated with GBS can inhibit nerve repair, thereby limiting functional recovery [102, 103]. Strategies to promote rapid Wallerian degeneration and accelerate axon regeneration may improve recovery in both nerve injury patients and GBS patients. Macrophage numbers are not increased around NMJs in the first 3 days after infusion of GBS-associated autoantibodies [71]. Therefore, macrophages may not be involved in NMJ damage in GBS; macrophage-mediated damage may occur at later time points or macrophages may be primarily involved in later regenerative processes. The roles of macrophages and inflammation in GBS are multifaceted, with the ability to cause both harm and healing. The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory effectors at different phases of NMJ reinnervation appear to be crucial to recovery from PNS damage due to autoimmunity or injury.

Conclusion

It has become apparent in recent years that macrophages are an essential component of nerve injury and regeneration. Their significance has been demonstrated at the injury site and in denervating disease pathology. The negative connotation associated with macrophages and inflammation is slowly changing as evidence emerges demonstrating non-detrimental functions of macrophages in disease. For nerve repair research, a new picture has developed, demonstrating the influence of both pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes. Different macrophage phenotypes contribute to different phases of nerve degeneration and regeneration, distinguished by differential growth factor expression, which influences the surrounding environment. In muscle, macrophages are thought to coordinate the activity of other immune cells in response to injury. Taken together, these data suggest that the role of macrophages at the NMJ includes both their traditional phagocytic role in addition to releasing cytokines and other factors to coordinate an immune response to denervation. Studying the roles of the various cell types at the NMJ during denervation and regeneration is imperative. Macrophages likely play a significant role at the NMJ, and therefore are good candidates for continued research. Influencing the polarization of macrophages at critical time points, for example, may be clinically useful to speed recovery. A more complete understanding of the interplay between the immune system and nerve repair may open new avenues for treatment and enhance target muscle recovery.

Table 1.

Summary of macrophage activity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

| ALS | SMA | GBS |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Highlights.

Macrophages are essential to nerve regeneration after injury or in denervating disease.

Different macrophage phenotypes contribute to different phases of nerve degeneration and regeneration, distinguished by differential growth factor expression, which influences the surrounding environment.

Macrophages likely play a significant role at the NMJ, and therefore are good candidates for future research.

A more complete understanding of the interplay between the immune system and nerve repair may open new avenues for treatment and enhance target muscle recovery.

Grant support:

Supported by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke K08NS096232 (to A.K.S.W.).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: Declarations of interest: none.

References

- 1.Padovano WM, et al. , Incidence of Nerve Injury After Extremity Trauma in the United States. Hand (N Y), 2020: p. 1558944720963895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akel BS, et al. , Health-related quality of life in children with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Qual Life Res, 2013. 22(9): p. 2617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmeister KD, et al. , Acute and long-term costs of 268 peripheral nerve injuries in the upper extremity. PLoS One, 2020. 15(4): p. e0229530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong TS, et al. , Indirect Cost of Traumatic Brachial Plexus Injuries in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2019. 101(16): p. e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta P, et al. , Prevalence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - United States, 2010–2011. MMWR Suppl, 2014. 63(7): p. 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Aguila MA, et al. , Prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology, 2003. 60(5): p. 813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy LV, et al. , Glial cells maintain synaptic structure and function and promote development of the neuromuscular junction in vivo. Neuron, 2003. 40(3): p. 563–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duregotti E, et al. , Mitochondrial alarmins released by degenerating motor axon terminals activate perisynaptic Schwann cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015. 112(5): p. E497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Son YJ and Thompson WJ, Nerve sprouting in muscle is induced and guided by processes extended by Schwann cells. Neuron, 1995. 14(1): p. 133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H, Tian L, and Thompson W, Terminal Schwann cells guide the reinnervation of muscle after nerve injury. J Neurocytol, 2003. 32(5–8): p. 975–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cattin AL, et al. , Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann Cell-Mediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell, 2015. 162(5): p. 1127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu CY, et al. , Macrophage-derived vascular endothelial growth factor-A is integral to neuromuscular junction reinnervation after nerve injury. J Neurosci, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale HH, Feldberg W, and Vogt M, Release of acetylcholine at voluntary motor nerve endings. J Physiol, 1936. 86(4): p. 353–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fertuck HC and Salpeter MM, Localization of acetylcholine receptor by 125I-labeled alpha-bungarotoxin binding at mouse motor endplates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1974. 71(4): p. 1376–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vannucci B, et al. , What is Normal? Neuromuscular junction reinnervation after nerve injury. Muscle Nerve, 2019. 60(5): p. 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer LR, et al. , Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: evidence in mice and man. Exp Neurol, 2004. 185(2): p. 232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swoboda KJ, et al. , Natural history of denervation in SMA: relation to age, SMN2 copy number, and function. Ann Neurol, 2005. 57(5): p. 704–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho TW, et al. , Motor nerve terminal degeneration provides a potential mechanism for rapid recovery in acute motor axonal neuropathy after Campylobacter infection. Neurology, 1997. 48(3): p. 717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki M, et al. , GDNF secreting human neural progenitor cells protect dying motor neurons, but not their projection to muscle, in a rat model of familial ALS. PLoS One, 2007. 2(8): p. e689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray LM, Talbot K, and Gillingwater TH, Review: neuromuscular synaptic vulnerability in motor neurone disease: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and spinal muscular atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2010. 36(2): p. 133–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jablonka-Shariff A, et al. , Gpr126/Adgrg6 contributes to the terminal Schwann cell response at the neuromuscular junction following peripheral nerve injury. Glia, 2020. 68(6): p. 1182–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dyke JM, et al. , Macrophage-mediated inflammation and glial response in the skeletal muscle of a rat model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Exp Neurol, 2016. 277: p. 275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trias E, et al. , Evidence for mast cells contributing to neuromuscular pathology in an inherited model of ALS. JCI Insight, 2017. 2(20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dachs E, et al. , Defective neuromuscular junction organization and postnatal myogenesis in mice with severe spinal muscular atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2011. 70(6): p. 444–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller M, et al. , Rapid response of identified resident endoneurial macrophages to nerve injury. Am J Pathol, 2001. 159(6): p. 2187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomlinson JE, et al. , Temporal changes in macrophage phenotype after peripheral nerve injury. J Neuroinflammation, 2018. 15(1): p. 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bombeiro AL, Pereira BTN, and de Oliveira ALR, Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor improves mouse peripheral nerve regeneration following sciatic nerve crush. Eur J Neurosci, 2018. 48(5): p. 2152–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage ND, et al. , Human anti-inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+ GITR+ CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress via membrane-bound TGFbeta-1. J Immunol, 2008. 181(3): p. 2220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin JW and George R, The resident macrophages in the peripheral nervous system are renewed from the bone marrow: new variations on an old theme. Lab Invest, 1993. 69(3): p. 257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ydens E, et al. , Profiling peripheral nerve macrophages reveals two macrophage subsets with distinct localization, transcriptome and response to injury. Nat Neurosci, 2020. 23(5): p. 676–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiguchi N, et al. , Epigenetic upregulation of CCL2 and CCL3 via histone modifications in infiltrating macrophages after peripheral nerve injury. Cytokine, 2013. 64(3): p. 666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills CD, et al. , M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol, 2000. 164(12): p. 6166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez FO and Gordon S, The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep, 2014. 6: p. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantovani A, et al. , The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol, 2004. 25(12): p. 677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verreck FA, et al. , Phenotypic and functional profiling of human proinflammatory type-1 and anti-inflammatory type-2 macrophages in response to microbial antigens and IFN-gamma- and CD40L-mediated costimulation. J Leukoc Biol, 2006. 79(2): p. 285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X, et al. , Polarizing Macrophages In Vitro. Methods Mol Biol, 2018. 1784: p. 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van den Bossche J, et al. , Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep, 2016. 17(3): p. 684–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazzan E, et al. , Dual polarization of human alveolar macrophages progressively increases with smoking and COPD severity. Respir Res, 2017. 18(1): p. 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porcheray F, et al. , Macrophage activation switching: an asset for the resolution of inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol, 2005. 142(3): p. 481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dort J, et al. , Macrophages Are Key Regulators of Stem Cells during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Diseases. Stem Cells Int, 2019. 2019: p. 4761427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrette B, et al. , Requirement of myeloid cells for axon regeneration. J Neurosci, 2008. 28(38): p. 9363–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brück W, Huitinga I, and Dijkstra CD, Liposome-mediated monocyte depletion during wallerian degeneration defines the role of hematogenous phagocytes in myelin removal. J Neurosci Res, 1996. 46(4): p. 477–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zigmond RE and Echevarria FD, Macrophage biology in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Prog Neurobiol, 2019. 173: p. 102–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu P, et al. , Role of macrophages in peripheral nerve injury and repair. Neural Regen Res, 2019. 14(8): p. 1335–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xuan W, et al. , The chemotaxis of M1 and M2 macrophages is regulated by different chemokines. J Leukoc Biol, 2015. 97(1): p. 61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller M, et al. , Macrophage response to peripheral nerve injury: the quantitative contribution of resident and hematogenous macrophages. Lab Invest, 2003. 83(2): p. 175–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee S, et al. , Targeting macrophage and microglia activation with colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor is an effective strategy to treat injury-triggered neuropathic pain. Mol Pain, 2018. 14: p. 1744806918764979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nadeau S, et al. , Functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury is dependent on the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF: implications for neuropathic pain. J Neurosci, 2011. 31(35): p. 12533–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boivin A, et al. , Toll-like receptor signaling is critical for Wallerian degeneration and functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci, 2007. 27(46): p. 12565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsieh CH, et al. , Knockout of toll-like receptor impairs nerve regeneration after a crush injury. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(46): p. 80741–80756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siqueira Mietto B, et al. , Role of IL-10 in Resolution of Inflammation and Functional Recovery after Peripheral Nerve Injury. J Neurosci, 2015. 35(50): p. 16431–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lv D, et al. , Sustained release of collagen VI potentiates sciatic nerve regeneration by modulating macrophage phenotype. Eur J Neurosci, 2017. 45(10): p. 1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mokarram N, et al. , Effect of modulating macrophage phenotype on peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials, 2012. 33(34): p. 8793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subang MC and Richardson PM, Influence of injury and cytokines on synthesis of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA in peripheral nervous tissue. Eur J Neurosci, 2001. 13(3): p. 521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taskinen HS and Röyttä M, Increased expression of chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, RANTES) after peripheral nerve transection. J Peripher Nerv Syst, 2000. 5(2): p. 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siebert H, et al. , The chemokine receptor CCR2 is involved in macrophage recruitment to the injured peripheral nervous system. J Neuroimmunol, 2000. 110(1–2): p. 177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan D, et al. , The CCL2/CCR2 axis is critical to recruiting macrophages into acellular nerve allograft bridging a nerve gap to promote angiogenesis and regeneration. Experimental Neurology, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keilhoff G, Wiegand S, and Fansa H, Vav deficiency impedes peripheral nerve regeneration in mice. Restor Neurol Neurosci, 2012. 30(6): p. 463–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lindborg JA, Mack M, and Zigmond RE, Neutrophils Are Critical for Myelin Removal in a Peripheral Nerve Injury Model of Wallerian Degeneration. J Neurosci, 2017. 37(43): p. 10258–10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niemi JP, et al. , A Critical Role for Macrophages Near Axotomized Neuronal Cell Bodies in Stimulating Nerve Regeneration. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2013. 33(41): p. 16236–16248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kano F, et al. , Secreted Ectodomain of Sialic Acid-Binding Ig-Like Lectin-9 and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Synergistically Regenerate Transected Rat Peripheral Nerves by Altering Macrophage Polarity. Stem Cells, 2017. 35(3): p. 641–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thoenen H, et al. , Nerve growth factor: cellular localization and regulation of synthesis. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 1988. 8(1): p. 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horie H, et al. , Oxidized galectin-1 stimulates macrophages to promote axonal regeneration in peripheral nerves after axotomy. J Neurosci, 2004. 24(8): p. 1873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stratton JA, et al. , Macrophages Regulate Schwann Cell Maturation after Nerve Injury. Cell Rep, 2018. 24(10): p. 2561–2572 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan D, et al. , Macrophages overexpressing VEGF, transdifferentiate into endothelial-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Biotechnol Lett, 2011. 33(9): p. 1751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharifi BG, et al. , Pleiotrophin induces transdifferentiation of monocytes into functional endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2006. 26(6): p. 1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barnett FH, et al. , Macrophages form functional vascular mimicry channels in vivo. Sci Rep, 2016. 6: p. 36659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Santosa KB, et al. , Clinical relevance of terminal Schwann cells: An overlooked component of the neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci Res, 2018. 96(7): p. 1125–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Son YJ, Trachtenberg JT, and Thompson WJ, Schwann cells induce and guide sprouting and reinnervation of neuromuscular junctions. Trends Neurosci, 1996. 19(7): p. 280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang H, et al. , Terminal Schwann cells participate in neuromuscular synapse remodeling during reinnervation following nerve injury. J Neurosci, 2014. 34(18): p. 6323–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cunningham ME, et al. , Perisynaptic Schwann cells phagocytose nerve terminal debris in a mouse model of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Peripher Nerv Syst, 2020. 25(2): p. 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Negro S, et al. , CXCL12α/SDF-1 from perisynaptic Schwann cells promotes regeneration of injured motor axon terminals. EMBO Mol Med, 2017. 9(8): p. 1000–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mogha A, et al. , Gpr126/Adgrg6 Has Schwann Cell Autonomous and Nonautonomous Functions in Peripheral Nerve Injury and Repair. J Neurosci, 2016. 36(49): p. 12351–12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chiu IM, et al. , Activation of innate and humoral immunity in the peripheral nervous system of ALS transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(49): p. 20960–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Graber DJ, Hickey WF, and Harris BT, Progressive changes in microglia and macrophages in spinal cord and peripheral nerve in the transgenic rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation, 2010. 7: p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nardo G, et al. , Immune response in peripheral axons delays disease progression in SOD1(G93A) mice. J Neuroinflammation, 2016. 13(1): p. 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tiemessen MM, et al. , CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(49): p. 19446–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu G, et al. , Phenotypic and functional switch of macrophages induced by regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice. Immunol Cell Biol, 2011. 89(1): p. 130–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henkel JS, et al. , Regulatory T-lymphocytes mediate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression and survival. EMBO Mol Med, 2013. 5(1): p. 64–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao W, et al. , Characterization of Gene Expression Phenotype in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Monocytes. JAMA Neurol, 2017. 74(6): p. 677–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Voigt T, et al. , Ultrastructural changes in diaphragm neuromuscular junctions in a severe mouse model for Spinal Muscular Atrophy and their prevention by bifunctional U7 snRNA correcting SMN2 splicing. Neuromuscul Disord, 2010. 20(11): p. 744–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murray LM, et al. , Defects in neuromuscular junction remodelling in the Smn(2B/-) mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol Dis, 2013. 49: p. 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murray LM, et al. , Selective vulnerability of motor neurons and dissociation of pre- and post-synaptic pathology at the neuromuscular junction in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet, 2008. 17(7): p. 949–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mishra VN, et al. , A clinical and genetic study of spinal muscular atrophy. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol, 2004. 44(5): p. 307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rees JH, et al. , Campylobacter jejuni Infection and Guillain–Barré Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 1995. 333(21): p. 1374–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yuki N, et al. , Carbohydrate mimicry between human ganglioside GM1 and Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide causes Guillain-Barre syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(31): p. 11404–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuwabara S, et al. , IgG anti-GM1 antibody is associated with reversible conduction failure and axonal degeneration in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol, 1998. 44(2): p. 202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jasti AK, et al. , Guillain-Barré syndrome: causes, immunopathogenic mechanisms and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 2016. 12(11): p. 1175–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halstead SK, et al. , Anti-disialoside antibodies kill perisynaptic Schwann cells and damage motor nerve terminals via membrane attack complex in a murine model of neuropathy. Brain, 2004. 127(Pt 9): p. 2109–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schluep M and Steck AJ, Immunostaining of motor nerve terminals by IgM M protein with activity against gangliosides GM1 and GD1b from a patient with motor neuron disease. Neurology, 1988. 38(12): p. 1890–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koike H, et al. , Ultrastructural mechanisms of macrophage-induced demyelination in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2020. 91(6): p. 650–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.HARTUNG H-P, et al. , THE ROLE OF MACROPHAGES AND EICOSANOIDS IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF EXPERIMENTAL ALLERGIC NEURITIS: SERIAL CLINICAL, ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL, BIOCHEMICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS. Brain, 1988. 111(5): p. 1039–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Griffin JW, et al. , Early nodal changes in the acute motor axonal neuropathy pattern of the Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurocytol, 1996. 25(1): p. 33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu S, Dong C, and Ubogu EE, Immunotherapy of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2018. 14(11): p. 2568–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xia RH, Yosef N, and Ubogu EE, Selective expression and cellular localization of pro-inflammatory chemokine ligand/receptor pairs in the sciatic nerves of a severe murine experimental autoimmune neuritis model of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2010. 36(5): p. 388–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orlikowski D, et al. , Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and chemokine receptor CCR2 productions in Guillain-Barré syndrome and experimental autoimmune neuritis. J Neuroimmunol, 2003. 134(1–2): p. 118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Susuki K, et al. , Anti-GM1 Antibodies Cause Complement-Mediated Disruption of Sodium Channel Clusters in Peripheral Motor Nerve Fibers. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2007. 27(15): p. 3956–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shen D, et al. , Beneficial or Harmful Role of Macrophages in Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Experimental Autoimmune Neuritis. Mediators of Inflammation, 2018. 2018: p. 4286364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Han R, et al. , Dimethyl fumarate attenuates experimental autoimmune neuritis through the nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2/hemoxygenase-1 pathway by altering the balance of M1/M2 macrophages. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2016. 13(1): p. 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Han R, et al. , RAD001 (everolimus) attenuates experimental autoimmune neuritis by inhibiting the mTOR pathway, elevating Akt activity and polarizing M2 macrophages. Experimental Neurology, 2016. 280: p. 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jin T, et al. , Bowman–Birk inhibitor concentrate suppresses experimental autoimmune neuritis via shifting macrophages from M1 to M2 subtype. Immunology Letters, 2016. 171: p. 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lehmann HC, et al. , Passive Immunization with Anti-Ganglioside Antibodies Directly Inhibits Axon Regeneration in an Animal Model. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2007. 27(1): p. 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lopez PH, et al. , Passive Transfer of IgG Anti-GM1 Antibodies Impairs Peripheral Nerve Repair. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2010. 30(28): p. 9533–9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]