Summary

Background:

Cabozantinib is a multikinase inhibitor of MET, VEGFR, AXL, and RET, which has also shown favorable effect in the tumor immune microenviroment by decreasing regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived supressor cells. In this study, we examined the activity of cabozantinib in patients with metastatic platinum-refractory urothelial carcinoma (mUC) and rare histology of the genitourinary (GU) tract.

Methods:

This was a single-arm, 3-cohort, phase II trial. Cohort 1 included patients with platinum-refractory mUC with measurable disease. Two additional cohorts were exploratory. Key eligibility criteria were age ≥18 years, histologically confirmed UC or rare GU tract histologies, Karnofsky Performance Scale Index of ≥60%, and documented disease progression. Patients must have failed at least 1 line of platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients received cabozantinib 60 mg orally once daily in 28-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary endpoint was objective response rate (ORR) in cohort 1. This completed study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01688999.

Findings:

Between September 28, 2012, and October, 20, 2015, 67 patients were recruited to the study. The median follow-up was 61.2 months (IQR: 53.8–70.0 months) for the 57 evaluable patients. In the 42 evaluable patients in cohort 1, there was one complete response and seven partial responses (ORR=19·1%; 95% CI 8·6–34·1). The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AEs) were fatigue (9%), HTN (7%), proteinuria (6%) and hypophosphatemia (6%).There were no treatment-related deaths.

Interpretation:

Cabozantinib has single-agent clinical activity in heavily pretreated platinum-refractory mUC patients with measurable disease and bone metastases and was generally well tolerated.

Funding:

NCI Intramural Program and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program.

Keywords: Cabozantinib, urothelial carcinoma, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, second-line, bladder cancer, innate and adaptive immunity

Introduction

Combination platinum-based chemotherapy has been the standard of care for chemotherapy-naïve patients with mUC and is associated with an OS of 9–15 months.1,2 Recently, five immune checkpoint inhibitors (atezolizumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab) have been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for platinum-refractory mUC patients,3–6 while atezolizumab and pembrolizumab have also been approved as first-line therapy in cisplatin-ineligible mUC patients with high expression of the protein programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1).7,8 Although some patients have durable responses, the ORR for these agents is a modest 14–23%.3–7 Erdafitinib is approved for platinum-refractory mUC patients with susceptible FGFR3/FGFR2 genetic alterations.9 Enfortumab vedotin, a nectin-4-directed antibody-drug conjugate, is now also approved for platinum- and immune checkpoint inhibitor-refractory mUC patients.10 Nevertheless, additional therapies and a better understanding of UC oncogenic drivers are urgently needed.

Elevated levels of VEGF and VEGFR are associated with an aggressive disease course and advanced-stage UC. Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors that block VEGF, such as sunitinib and sorafenib, have an ORR of <10% either as first- or second-line therapy, while pazopanib showed a 17% response rate and OS of 4·7 months as second-line therapy in mUC.9 Angiogenesis inhibitors potentiate the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin in urothelial cell lines. Bevacizumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF-A) has been evaluated with gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) as first-line therapy in a phase III trial. The addition of bevacizumab to GC did not improve an OS of 14·5 vs 14·3 months, HR 0·87, p=0·17.11 In a single-arm study in cisplatin-ineligible chemotherapy-naive patients, bevacizumab combined with GC led to a 63% response rate and an OS of 13·9 months.12 The addition of sunitinib or pazopanib to chemotherapy resulted in excessive toxicity or lack of efficacy in the metastatic setting.13–15

MET signaling pathway has been implicated in UC’s pathogenesis, andthe multikinase inhibitor cabozantinib (approved for first-16 and second-line metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma,17 progressive medullary thyroid cancer,18 and advanced progressive hepatocellular carcinoma),19 has been shown to suppress HGF/MET-mediated tumor-cell growth in UC xenograft models.

Based on preclinical results in UC, clinical activity in other solid tumors, and the potential for a therapeutic effect of cabozantinib on immune dysfunction in UC, we conducted a phase II, single-arm clinical trial to determine the clinical activity of cabozantinib in patients with platinum-refractory mUC with measurable disease, bone-only metastases, and rare variant histologies of the GU tract.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a phase II, single-arm, single-institution, open-label study of cabozantinib in patients with mUC and rare GU tract malignancies (including the renal pelvis, ureter, urinary bladder, or urethra). Cohort 1 had patients with mUC and measurable disease defined by RECIST v1·1. Cohorts 2 and 3 were exploratory, and patients were enrolled in parallel to cohort 1. Cohort 2 patients had bone metastases with no measurable disease and at least one new bone lesion. Cohort 3 patients had measurable metastatic rare variant histologies of the GU tract. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older, with histological confirmation of mUC or a rare variant histology of the GU tract and had progressed after at least one cytotoxic chemotherapy. Further inclusion criteria were a Karnofsky performace status of ≥ 60% and mesurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1·1 for cohorts 1 and 3. Blood tests included a blood cell count alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase, albumin, bilirubin, creatinine, and urea nitrogen. A 3-week washout period for previous chemotherapy or biologic agents, was mandatory. Key exclusion criteria were a history of current active central nervous system metastases, previous treatment with cabozantinib, extrenal radiation of the thoracic cavity or gastrointestinal tract within 3 months of study treatment, and receipt of any small molecule kinase inhibitor of VEFGR within 2 years of study enrollment.

The study was approved by the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Ethics Committee. It was conducted in conformance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All patients signed informed consent. This study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01688999).

Procedures

Cabozantinib was administered orally at 60 mg/day for 28 consecutive days in all cohorts. Treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, the investigator’s decision to discontinue, or withdrawal of patient consent. Adverse events were graded per the NCI’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4·0.Safety evaluations (physical exam, vital signs, laboratory tests, adverse event assessment) and electrocardiogram were performed every two weeks for the first 15 weeks and every four weeks thereafter. Cabozantinib could be reduced to 40 mg, and then 20 mg/day. Dose interruptions were also allowed for up to > 6 weeks only. A safety follow-up by telephone was scheduled 30–37 days after treatment discontinuation; patients were contacted every two months to obtain survival information.

In all cohorts, tumors were assessed by CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis or CT chest and MRI abdomen and pelvis at baseline and every eight weeks until disease progression or treatment discontinuation. 18F-sodium fluoride (NaF) PET/CT20,21 scans were performed on all patients at baseline and subsequently on patients with bone metastases. Protocol amendments included 10/19/2012: urine protein-creatinine ratio eligibility increased from ≤1 to ≤2; 10/01/2013: palliative radiation therapy was allowed on study; 1/25/2018 allowed patients in CR lasting > 3 years to hold cabozatininb until relapse, with scans to be done every 12 weeks instead of every 8 weeks.

Outcomes

For cohorts 1 and 3, the primary endpoint of this study was the proportion of patients with an ORR based on investigator-assessed RECIST v1·1. Best overall response was defined as the best response obtained from the start of treatment to the time of progression and was categorised as complete response, partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease.

Secondary endpoints included OS, PFS, and safety. OS was defined as the time between the date of treatment initiation and the date of death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to the date of the first documented tumor progression, or death from any cause. A post-hoc analysis of ORR by metastatic site in 61 RECIST target lesions from 42 patients with mUC (cohort 1) included 27 visceral metastatic sites (15 lung, 7 liver, 1 pancreas, 4 adrenal gland) and 34 non-visceral metastatic sites (23 lymph nodes and 11 soft tissue). Another secondary endpoint, to compare alternative radiologic criteria to RECIST for assessing radiologic response, has been published.22 A further secondary endpoint, the use of FDG PET/CT to assess response, will be published elsewhere.

For patients in cohort 2, a bone lesion was considered positive if there was focal NaF uptake correlated with CT. At each scan, the number of lesions, bone anatomical site, maximum standardized uptake value (SUV), and serum alkaline phosphatase were captured. Bone response to therapy was defined as a decrease in the number of bone lesions from baseline. Bone-stable disease was defined as no change or one new bone lesion. Two new bone lesions on NaF PET/CT associated with characteristic bone changes on CT scan were defined as bone-progressive disease (PD). NaF uptake changes, including changes in SUV or flares of known baseline lesions, were not counted as PD.

Prespecified, exploratory analyses of potential plasma biomarkers of cabozantinib were performed as detailed below. Isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cell immune subsets were assessed using multiparameter flow cytometry for effector T cells, exhausted T cells, Tregs, and MDSCs, including the functional markers PD-1 and TIM-3 (see Appendix p3). Plasma and urine concentrations of HGF/MET were assessed using a two-site electrochemiluminescent immunoassay.23 Plasma levels VEGF-A, soluble VEGFR2, placental growth factor (PIGF), and inflammatory cytokines were analyzed (Appendix p5). Epithelial cell adhesion molecule-positive CTCs were detected using multiparameter flow cytometry, as previously described (Appendix p6).24

Statistical analysis

Cohort 1 of the study was conducted as a Simon optimal 2-stage design with alpha=0·05 and beta=0·10 as acceptable error probabilities. All enrolled patients who received at least one dose of cabozantinib were included in the safety analysis. The efficacy population included all participants who met the eligibility criteria and who received at least 8 weeks of therapy. For the primary endpoint of ORR, the study was designed to rule out an unacceptably low 5% ORR (p0=0·05) in favor of a modest response rate of 20% ORR (p1=0·20). Two or more responses in the first 21 patients would permit enrollment to a total of 41 evaluable patients, with others allowed if needed to replace unevaluable subjects. For cohort 2, changes from baseline to the time of best response for SUV and the lesion number were compared between bone response and bone-stable disease (SD) vs bone-PD using an exact Wilcoxon rank sum test. Because small sample size was expected for cohorts 2 and 3, data analysis was exploratory.

We estimated PFS and OS using the Kaplan-Meier method. Exploratory analyses were performed to establish an association between clinical factors and PFS or OS. Biomarker analyses were exploratory and performed in patients from all cohorts when samples were available. The association between PFS and OS with plasma and urine HGF/MET baseline values and changes from baseline to weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 were determined using Kaplan-Meier curves and two-tailed, unadjusted as well as adjusted log-rank p values to account for combined groups formed after seeing initial results. The cutoff of five CTCs/sample was used as previously described.25 Genotypes were compared to toxicity (>20% incidence rate) using the Fisher’s exact test or the Cochran-Armitage test.

In post-hoc analyses, we investigated differences in response to cabozantinib treatment according to clinical factors with prognostic relevance: Bellmunt risk stratification, which includes 3 poor risk factors (hemoglobin levels, PS, and presence of liver metastatses), cisplatin fitness prior to first-line therapy or prior radical surgery (radical cystectomy/cystoprostatectomy, radical nephrectomy/nephroureterectomy) of the primary tumor. We also analyzed the relationship between the presence of visceral disease and subsets of MDSCs.

Estimated parameters were reported with 2-sided 95% CIs. p values < 0·05 (typically ≤0·05) were interpreted as being statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using SAS version 9·4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Role of the funding source

The Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP), National Cancer Institute (NCI) provided cabozantinib under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement established with Exelixis. CTEP was the sponsor of the study and was involved in the study design but did not have a role in data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. ABA, RRN, JBT, LC, SLL, MJL, RC, DPB, and SMS had access to the raw data. All authors, except ND, were employed by the NIH during the conduct of this study.

Results

Between September 28, 2012, and October, 20, 2015, 68 patients were enrolled and 67 were eligible (1 patient was deemed ineligible prior to Cycle (C)1Day (D)1 when a lymph node biopsy diagnosed metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma). Baseline characteristics for all patients and each cohort are summarized in Table 1. All 67 patients received at least one dose of cabozantinib and were evaluable for safety; the median follow-up was 61·2 months (IQR: 53·8 –70.0 months) for the 57 evaluable patients. Patients unevaluable for response included 5 (4 in cohort 1, and 1 in cohort 2) who withdrew prior to first restaging; 5 who were discontinued before first restaging due to AEs regardless of attribution.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and previous treatment

| Patient Characteristics | All Cohorts N=67 | Cohort 1 N=48 | Cohort 2 N=6 | Cohort 3 N=13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Median | 63 | 63 | 66 | 57 |

| Range | 22–82 | 35–82 | 54–70 | 22–74 |

| Gender | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| Male | 47 (70) | 33 (69) | 5 (83) | 9 (69) |

| Female | 20 (30) | 15 (31) | 1 (17) | 4 (31) |

| KPS | ||||

| 90% | 10 (15) | 8 (17) | 0 | 2 (15) |

| 80% | 48 (71) | 33 (69) | 5 (83) | 10 (77) |

| 70% | 5 (8) | 4 (8) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| 60% | 4 (6) | 3 (6) | 1 (17) | 0 |

| Primary Tumor Site | ||||

| Bladder | 47 (70) | 30 (63) | 5 (83) | 12 (92) |

| Upper tract: renal pelvis or ureter | 17 (25) | 16 (33) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| Bladder & upper tract | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | 1 (17) | 0 |

| Type of Metastases | ||||

| Lymph node only | 10 (15) | |||

| Any visceral metastases | 57 (85) | |||

| Sites of Metastatic Disease | ||||

| Lymph node | 47 (79) | 40 (80) | 0 | 7 (54) |

| Bone | 15 (22) | 6 (12) | 6 (100) | 3 (23) |

| Lung | 24 (36) | 19 (40) | 0 | 5 (38) |

| Liver | 17 (25) | 10 (21) | 0 | 7 (54) |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1(8) |

| Soft tissue masses (abdominal, pelvic, and muscle) | 21 (31) | 17 (35) | 0 | 4 (31) |

| No. of Prior Therapies for Metastatic Disease* | (range 1–6) | (range 1–6) | (range 1–3) | (range 1–5) |

| 1 | 25 (37) | 17 (35) | 3 (50) | 5 (39) |

| 2 | 25 (37) | 19 (40) | 1 (17) | 5 (38) |

| 3 | 11 (17) | 7 (15) | 2 (33) | 2 (15) |

| 4 or more | 6 (9) | 5 (10) | 0 | 1 (8) |

One patient received immune-checkpoint inhibitors within a clinical trial prior to enrollment

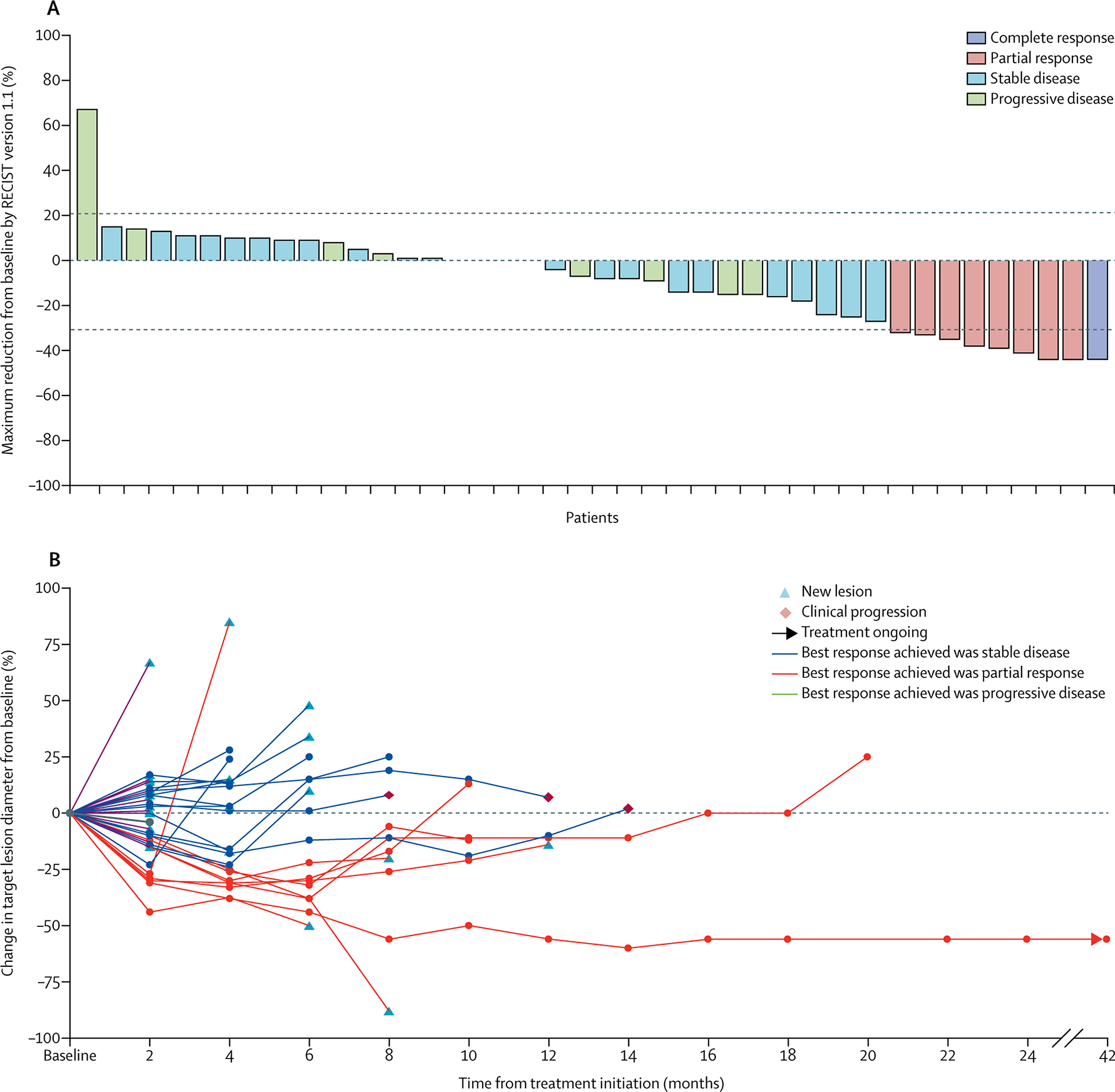

In cohort 1, 3 responses were seen in the first 21 patients in stage 1; therefore, we moved to stage 2 with a total of 42 evaluable patients. The ORR based on investigator-assessed RECIST v1·1 was 19·1% (95% CI 8·6–34·1) (Figure 1A and 1B), with one complete response (CR) and seven partial responses (PR). At the time of data cutoff on March 13, 2019, two patients remained alive. One had a CR (and remains in CR on study, but had cabozantinib discontinued after 3·5 years) and one had SD for eight months on cabozantinib and subsequently achieved a CR to combination immunotherapy with a checkpoint inhibitor. Forty patients died due to disease progression during the study period. Nineteen patients (45·2%) had SD as best response, clinical benefit (PR+CR+SD) was 64·3% (95% CI 48·0–78·5), and 35·7% of patients had PD. Three of the five patients in cohort 2 (60%) had bone response by NaF FDG/PET. Five of ten evaluable patients with rare histologies (50%) had SD. Some patients did not achieve a response by RECIST but had tumor cavitation, suggesting tumor necrosis (Appendix p10). Many patients had their dose of cabozantinib reduced from 60 mg/day with persistent efficacy (Table 2 and Figure 2). ORR by metastatic site: lung metastases showed ORR: 4/15 (27%) (PR); lymph node 2/23 (9%) (CR) and 2/23 (9%) (PR) total lymph node ORR 17%. Non-lung visceral disease and soft tissue metastasis had SD as a best response (Appendix p7). Patients with lymph node-only disease or lymph nodes or lung disease had improved PFS compared to those with other forms of metastatic disease: median 6·5 months (95% CI 1·8–13·8) vs 3·7 months (95% CI 1·9–5·3), p=0·038 and 3·6 months (95% CI 1·9–5·1) vs 6·5 months (95% CI 2·3–11·3), p=0·0053, respectively. OS improvement was not statistically different between these groups: 11.6 months (95% CI 6·5–36·1) vs 7·9 months (95% CI 4·6–9·7), p=0·14 for lymph node-only vs other metastases and 11·6 months (95% CI 6·5–17·3) vs 7·2 months (95% CI 4·6–9·3), p=0·07, in patients with lymph nodes or lung disease vs other visceral metastases, respectively.

Figure 1. Cabozantinib antitumor activity in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and measurable disease.

A. Waterfall plot of reduction in target lesions in 42 patients with urothelial cancer and measurable disease in cohort 1.

B. Spider plot providing response, presence of new lesions (yellow triangle), clinical progression (orange diamond), and ongoing responses (black arrow).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory adverse events

| Clinical Adverse Events (N=67) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

| Clinically Significant | |||||

| Fatigue | 20 (30%) | 20 (30%) | 6 (9%) | ||

| Diarrhea | 29 (43%) | 14 (21%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Hypertension | 5 (7%) | 6 (9%) | 5 (7%) | ||

| Mucositis (oral) | 10 (15%) | 6 (9%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Nausea | 21 (31%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Anorexia | 11 (16%) | 8 (12%) | |||

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia | 33 (49%) | 22 (33%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Pulmonary embolus | 1 (1%) | ||||

| Recto-vaginal fistula | 1 (1%) | ||||

| Anal fissure/scrotal ulcer | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | |||

| Dysgeusia | 19 (28%) | ||||

| Hoarseness/voice alteration | 16 (24%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Weight loss | 6 (9%) | 2 (3%) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 9 (13%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Hair/skin lightening | 7 (10%) | ||||

| Muscle cramps/myalgias | 8 (12%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Laboratory Adverse Events (N=67) | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

| Clinically Significant | |||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increase | 37 (55%) | 3 (4%) | |||

| Creatinine increase | 18 (27%) | 7 (10%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Hypomagnesemia | 13 (19%) | 6 (9%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Hyponatremia | 14 (21%) | 2 (3%) | |||

| Hypophosphatemia | 29 (43%) | 4 (6%) | |||

| Lipase increase | 6 (9%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Amylase increase | 7 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Lymphocyte count decrease | 6 (9%) | 5 (7%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Neutrophil count decrease | 10 (15%) | 7 (10%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Platelet count decrease | 30 (45%) | 6 (9%) | 3 (4%) | ||

| Anemia | 35 (52%) | 18 (27%) | |||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 29 (43%) | 8 (12%) | |||

| Proteinuria | 3 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) | ||

| Hyperthyroidism | 5 (7%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 8 (12%) | 19 (28%) |

Figure 2. Tumor response to cabozantinib by dose in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and measurable disease.

Swimmers plot showing dose and duration of treatment in responders and non-responders by RECIST v1·1

The mPFS for patients in cohort 1 was 3·7 months (95% CI 3·1–6·4). The six- and 12-month PFS was 37·0% (95% CI 22·7–51·5) and 9·9% (95% CI 3·1–21·2), respectively. mOS was 8·1 months (95% CI 5·2–10·3) (Figure 3). Six- and 12-month OS were 64·3% (95% CI 47·9–76·7) and 26·2% (95% CI 14·1–40·0), respectively, for patients with measurable mUC.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival and overall survival for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma and measurable disease.

A. Progression-free survival. Of 42 patients evaluated, 40 progressed and 2 were censored for progression at 2·8 and 57·3 months, respectively. B. Overall survival: of 42 patients evaluated, 40 have died and 2 remain alive at 52·0 and 57·3 months, respectively.

In cohort 2, 3/5 patients (60%) had a decrease in the number of lesions by NaF FDG/PET (Appendix p11). Their mPFS and mOS were 5·3 months (95% CI 1·8–8·3) and 9·3 months (95% CI 4·6–12·5), respectively, and six-month OS was 80·0% (95% CI 20·4–96·9). Twenty-two patients had bone metastases at baseline (6 bone-only, 16 bone and soft tissue), including 17 with UC and five with small cell bladder cancer. Among the 22 patients, 147 bone lesions were predominantly distributed in the spine, ribs, and pelvis (Appendix p12). Fifteen patients (five bone-only; 10 bone and soft-tissue metastases) had a follow-up NaF PET/CT (7 without NaF follow-up included 3 with clinical progression, 2 with soft-tissue progression on CT CAP, 1 who withdrew, and 1 with grade 3 toxicity). Five of these 15 patients (33%) with follow-up had a decreased number of bone lesions on NaF PET/CT and remained on study 238, 252, 182, 161, and 56 days, respectively; 4/15 (27%) had SD on both CT CAP and NaF PET/CT, and 6/15 (40%) had PD either on CT CAP or NaF PET/CT as best response. There was no association between PFS or OS and baseline, number of NaF lesions (p=0·74 and p=1·00, respectively), NaF SUV (p=0·94 and p=0·14, respectively), or serum alkaline phosphatase levels (p=0·82 and p=0·33, respectively). Seventeen patients with bone disease and UC had an mOS of 7·2 months (95% CI 4·1–10·8 months) and an mPFS of 3·9 months (95% CI 1·8–7·8 months).

No differences in OS were found in patients who underwent radical surgery of the primary tumor (n=33): median OS 8·2 months (95% CI 6·5–10·8) vs no surgery (n=14): 8·9 months (95% CI 3·6–16·8), p=0·83, or cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy: 8·9 months (95% CI 6·5–10·8) vs non-cisplatin-based first-line therapy: 6·4 months (95% CI 2·9–36·1), p=0·48.

Among patients treated with cabozantinib, there were significant differences in PFS and OS between patients with one Bellmunt poor risk factor and those with 2 or 3 risk factors (p=0.01 for PFS and p=0·02 for OS).26 Patients with liver metastases had a significantly shorter PFS (p=0·0012) and OS (p=0·0078) than patients with no liver metastases.

In cohort 3 patients with rare bladder cancers and other rare GU tumors, mPFS was 2·9 months (95% CI 1·8–3·7) and mOS was 5·8 months (95% CI 2·6–8·1). Three- and 6-month PFS was 50·0% (95% CI 18·4–75·3) and 10·0% (95% CI 0·6–35·8), respectively; six-month OS was 50·0% (95% CI 18·4–75·3). All patients from cohorts 2 and 3 died due to disease progression during the study period.

Across the three cohorts, 45/67 patients (67%) treated at the initial dose of cabozantinib had at least one dose reduction while on study. Three patients (4·5%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events, and 50/67 patients (75%) required dose delays (median treatment delay: 5 days; IQR: 5–10 days). All-cause, any grade AEs were reported in all patients, with 45 (67%) patients experiencing a grade 3–4 adverse event. No treatment-related deaths were observed (Table 2). Most treatment-related AEs were mild to moderate in nature, with palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (56 [83%]), anemia (53 [79%], fatigue (46 [69%]), diarrhea (45 [67%]), AST increase (40 [59%]), hypoalbumineamia (37 [55%] and nausea (25 [36%]) among the most common any-grade adverse events. The incidence of grade 3–4 treatment-related AEs was low, fatigue being the most common, occurring in 6 patients (9%), followed by HTN (7%), proteinuria (6%), and hypophosphatemia (6%) (Table 2).

Exploratory translational analyses showed that cabozantinib decreased classical monocytes and increased non-classical monocytes (Appendix p13–14. MDSC populations (Appendix p15). decreased with cabozantinib, and a low granulocytic MDSC population at baseline was associated with an OS improvement (Figure 4). The presence of visceral disease (lung, bone, or liver metastasis) did not have an impact on the baseline percent of any MDSC subtype (data not shown). Cabozantinib decreased the percent of Tregs among CD4+ T cells (Appendix p16), while increasing the ratio of effector CD8+ T cells to Tregs (Appendix p17). Cabozantinib significantly increased the expression of PD-1 on Tregs (Appendix p18) and downregulated TIM-3 on Tregs (Appendix p18). Low TIM-3 levels on Tregs at baseline were associated with improved OS (Appendix p18). No other levels of baseline expression or changes or changes in immune subsets post-therapy were associated with PFS, OS, or ORR. In vitro, cabozantinib suppressed IL-10 and HGF gene expression in CD14+ monocytes (Appendix p19). The association between baseline low (≤1480) urine HGF (p=0·14) with PFS, 5·9 months (95% CI 1·8–12·1 months) vs 3·7 months (95% CI 1·9–5·1 months) and OS (p=0·22) 8·7 months (95% CI 4·6–14·8 months) vs 7·5 months (95% CI 4·1–9·3 months) is shown in Appendix p20–21. Plasma MET/HGF and urine MET levels were not associated with PFS or OS (data not shown).

Figure 4. Peripheral immune subset modulation by cabozantinib.

Kaplan-Meier plot for overall survival of dichotomized granulocytic MDSCs (gMDSC) at baseline. gMDSCs < median: 9·43 months (95% CI: 6·70–12·52 months); > median: 5·81 months (95% CI: 4·07–8·48 months); p=0·0026. Log-rank test was used for estimations.

Levels of PlGF (+122%; p<0·0001 C1D15, C1D29) and VEGF (+35% p<0·0001 C1D15, C1D29 p=0·30) increased with cabozantinib. This induction was more sustained (C1D15, C1D29) for PlGF than with VEGF (C1D15 only). Levels of TNFα (–17% p<0·0001; C1D15 and C1D29) decreased with cabozantinib (Appendix p22–23). High baseline levels of circulating IL-6 (upper 3 quartiles) were associated with lower mOS: 7·0 months (95% CI 4·4–8·9); vs 19·3 months (95% CI 8·0- not estimable) for the lower quartile p=0·0017 unadjusted p=0·0051 adjusted (Appendix p24). No significant changes in other angiogenic factors or inflammatory cytokines were noted over time. A baseline CTC count of <5 vs ≥5 was associated with longer PFS(p=0·042, HR 0·55; 95% CI: 0·29–1·01) and longer OS (p=0·0079, HR 0·43) (Appendix p25–26).

For MET expression, 67 specimens from 46 patients were analyzed by IHC (40 in cohort 1 and 6 in cohort 3 (3 bladder small cell, 1 bladder squamous cell carcinoma, 1 bladder sarcomatoid, 1 bladder adenocarcinoma); 39% were positive and 61% were negative for MET. In a patient-based analysis (n=46), 43% of patients had paired tumor samples (primary vs metastatic site or different metastatic sites). Of these, 75% of matched patient specimens were both positive for MET by IHC. Eleven patients with 17 specimens had clinical benefit (6 PR, 3 bone responses, 4 SD >8 months) and 35 patients with 50 specimens had no clinical benefit (PD or SD < 8 months). MET IHC was positive in 65% of patients with a clinical benefit and 55% of patients with no clinical benefit. IHC scores differed in specimens from different organ sites within the same patient in about 50% of patients.

Hypophosphatemia was more frequent in patients with the 634C/C and C/G genotypes (n=15/25, 29·4%) than in patients with the G/G genotype (n=5/26, 9·8%; p=0·0042) (Appendix p9–10). In the 50-gene panel, common mutations were seen in TP53 (56%), PIK3CA (25%), FGFR3 (13%), KRAS (13%), HRAS (13%), RB1 (6%), and EGFR (6%). MET mutations were not found in this patient cohort.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that cabozantinib has clinical activity and leads to responses in patients with advanced platinum-refractory mUC. The study met its primary endpoint of an improved ORR (19%) compared with 10–15% with second-line chemotherapy. Also, the observed clinical benefit was 64·3%. Soft tissue responses were seen predominantly in lymph nodes and lung. The mPFS of 3·7 months and mOS of 8·1 months seen with cabozantinib are similar to mUC platinum-refractory patients treated with second-line chemotherapy (PFS 3·3 months and OS 7·4 months).5

Treatment with cabozantinib often caused tumor necrosis in responding metastases, manifested as density attenuation changes on imaging. Standard tumor response assessment with RECIST underestimated responses, especially in the lung, where lesions often cavitated (Appendix p10) and did not meet RECIST criteria for response. Alternative radiologic methods of measuring response that take tumor necrosis into consideration may help to more accurately assess response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as cabozantinib.22

Cabozantinib also demonstrated clinical activity in patients with bone metastases. In preclinical studies, cabozantinib treatment inhibited the growth of prostate tumor xenografts in bone and resulted in changes to the bone microenvironment, including a biphasic effect on osteoblast activity, inhibition of osteoclast production, and changes in bone remodeling.27,28 A third of patients in this study had bone metastases either mixed with soft tissue or bone-only disease. A cohort of patients with UC with bone-only disease (cohort 2) had improvement in their bone metastases as assessed by NaF FDG/PET (Appendix p11). Quantifying response using NaF FDG/PET is an active area of investigation.20 We also enrolled patients with rare GU tumors in cohort 3 (Table 1). Although no objective response was seen, half the patients had SD, most likely related to the different underlying oncogenic drivers in these histologies compared to UC. The primary limitation to this study is the absence of randomization and a control group. Another limitation is the small size of the exploratory bone-only and rare GU tumor patient cohorts.

In this study, cabozantinib’s safety profile and common adverse events were similar to those previously reported.16–19 Across the three cohorts, 2/3 of patients had at least one dose reduction and 3/4 had dose delays. Fatigue, dysgeusia, anorexia, and weight loss were commonly seen. Diarrhea was well managed with antidiarrhea medication. Electrolyte issues such as hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, and hyponatremia were commonly seen and managed with hydration and repletion. Hypo- and/or hyperthyroidism were also common. TSH and free T4 should be followed while on therapy.29 Skin manifestations were common and manageable.30 One patient developed a rectal-vaginal fistula, two patients developed scrotal ulcers, and one had an anal fissure; all resolved on discontinuation of cabozantinib.

Cabozantinib modulated peripheral blood myeloid populations, including decreasing classical monocytes, increasing nonclassical monocytes, and decreasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cabozantinib also favorably impacted CD4 polarization to decrease regulatory T cells (Tregs), increase the ratio of CD8 T cells to Tregs, and upregulate PD-1 expression on Tregs. MDSCs and Tregs are major components of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and both may promote effector T-cell dysfunction and tumor progression. In a previous study of peripheral immune cells in triple negative breast cancer patients treated with cabozantinib had an increase in CD8+ T cells and decrease in CD14+ monocytes.31 However, protumorigenic (classical) monocytes were not distinguished from monocytes with antitumor activity (intermediate and nonclassical monocytes).32 We found cabozantinib specifically decreased protumorigenic classical monocytes and increased antitumor non-classical monocytes (Appendix p14). Furthermore, cabozantinib decreased MDSC populations (Appendix p15). A greater-than-median decrease in the granulocytic MDSC population was significantly associated with a favorable OS (Figure 4).

Although there is considerable evidence of HGF-MET signaling in various aspects of the UC malignant phenotype, the level of MET in UC tumors has not proven to be a reliable predictor of sensitivity to MET inhibition. We did not find an association between clinical outcomes and MET protein expression by IHC or plasma. Interestingly, MET is also expressed in immune cells, such as CD14+ monocytes, where HGF and MET may form an activating autocrine loop and cabozantinib may potentially inhibit autocrine oncogenic signaling. HGF-MET signaling in monocytes induce IL-10,33 which has been shown to be an immunosuppressant in UC.34 In healthy controls, cabozantinib suppressed IL-10 gene expression in isolated CD14+ monocytes. IL-10 expression in isolated monocytes was also inhibited by MET-specific small interfering RNA with a magnitude similarto cabozantinib, suggesting cabozantinib targets the HGF-MET-IL-10 axis in CD14+ monocytes (Appendix p19). In addition, cabozantinib suppressed HGF gene expression in CD14+ monocytes (Appendix p19). Together, these data suggest that cabozantinib inhibits an autocrine-paracrine system of HGF-MET-IL-10 signaling in CD14+ monocytes.

HGF-MET signaling in dendritic cells (DCs) induces tolerogenic DCs, which secrete high levels of IL-10 and facilitate the expansion of Tregs.24 Thus, at least two immune pathways are driven by HGF-MET signaling that can induce expansion of immunosuppressive Tregs. Cabozantinib significantly decreased the percent of Tregs among CD4+ T cells (Appendix p16), while increasing the ratio of effector CD8+ T cells to Tregs (Appendix p17).

PD-1, a negative regulator of effector T cells, can also act as a negative regulator of Tregs in the tumor microenvironment.35 Cabozantinib significantly increased the expression of PD-1 on Tregs (Appendix p18), consistent with decreasing Treg immunosuppressive activity. In contrast, the checkpoint TIM-3, which strongly enhances immunosuppressive activity of Tregs, was significantly downregulated on Tregs by cabozantinib. Furthermore, the expression level of TIM-3 on Tregs at baseline was prognostic of OS in this study.

Our exploratory analysis of urine HGF found a trend toward improved outcome with baseline low urine HGF (Appendix p20–21). However, neither urine MET levels nor plasma HGF/MET levels were associated with outcome. Baseline CTCs of <5 were associated with prolonged PFS and OS. However, changes in CTCs during treatment were not associated with treatment response or outcome. Circulating cytokines, specifically interleukins, have prognostic value in many tumors. In our study, baseline high circulating IL-6 levels was associated with a shorter OS. The increase in PlGF levels (Appendixp22) may be associated with VEGFR1 inhibition, which triggers the feedback regulation of PlGF. The correlative studies are hypothesis-generating and have several limitations, including no control arms or comparison with serial changes.

Treatment with cabozantinib was well tolerated and associated with clinical activity, including an ORR, PFS, and OS comparable to second-line chemotherapy. There was also activity in patients with bone metastases. This report showed that cabozantinib has innate and adaptive immunomodulatory properties that may counteract tumor-induced immunosuppression, providing a rationale for combining cabozantinib with immunotherapeutic strategies. Several ongoing trials are testing this concept.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We did a literature research in PubMed for published preclinical and clinical reports, with no restrictions on article type or language, from database inception until September 01, 2019, using the terms “MET alterations”, “cabozantinib”, “ genitourinary malignancies” and “urothelial carcinoma”. Various targeted therapies, including antiangiogenic drugs targeting VEGF and its receptors, have showed no benefit in urothelial carcinoma. Cabozantinib is an oral multityrosine kinase inhibitor of MET, VEGFR, AXL, and RET kinase activity. In addition to its tyrosine kinase inhibition, cabozantinib may alter the tumor immune microenvironment, altering regulatory T cells as well as myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Preclinical work demonstrates that urothelial cell MET content in cultures increases with disease grade, and that HGF-stimulated activation of MET and known effectors leads to enhanced invasion, growth rate, and anchorage-independent growth. In vitro, cabozantinib effectively reverses these HGF-driven effects. To the best of our knowledge, no previous trials assessing the activity of cabozantinib or other drugs targeting MET in urothelial carcinoma and other rare genitourinary malignancies have been published.

Added value of this study

Our results show that cabozantinib, which is already approved for the management of medullary thyroid cancer, renal cancer, and hepatocarcinoma, has clinical activity in patients with platinum-refractory mUC with soft tissue and bone metastases and in other rare genitourinary malignancies. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate a therapy targeting both angiogenic and MET receptor in these patient populations. This work also reports correlative studies demonstrating the immunomodulatory properties of cabozantinib by profiling peripheral blood immune subsets.

Implications of all the available evidence

The clinical activity observed in this study provides a basis for further clinical investigations of cabozantinib for the treatment of mUC and other patient populations with rare genitourinary malignancies. Ongoing studies combining cabozantinib with immne-checkpoint inhibitors may lead to new therapeutic options for patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma and rare genitourinary malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, NCI, National Institutes of Health, and by a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the NIH’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and the NCI. We thank the patients involved in this study and their families. We express appreciation to the nurses, medical oncology fellows, and consultation services at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center for their excellent patient care. We thank Bonnie L. Casey from the NCI for editorial assistance. Exelixis provided the study drug.

Conflict of Interest Statement

DPB has a patent 10,035,833 issued, a patent 9,550,818; WO/2013/163606 issued, a patent 8,617,831 issued, a patent 8,569,360; WO/2009/124024, 124013 issued, a patent 8,304,199 issued, a patent 7,964,365; WO/2007/056523 issued, and a patent 7,871,981; WO/2001/028577 issued. LRF has an issued patent on a CT window level and an issued patent on a radiographic marker that displays upright angle on portable radiology and has Research agreement with Carestream Health.NND is emplyeed by Genentech and holds stock. NAD reports personal fees from Exelixis, outside the submitted work

Footnotes

Data Sharing

De-identified individual participant data which underlies the results reported in this Article and the study protocol will be available beginning 3 years after publication because of ongoing research, and subject to sponsor approval. Data will be made available to investigators who develop methodologically sound proposals. Proposals should be directed to andrea.apolo@nih.gov

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Andrea B. Apolo, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Rosa Nadal, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Yusuke Tomita, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Nicole N. Davarpanah, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Lisa M. Cordes, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Seth M. Steinberg, Biostatistics and Data Management Section, National Cancer Institute 9609 Medical Center Drive, Room, 2W334, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Liang Cao, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Howard L. Parnes, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Rene Costello, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Maria J. Merino, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Les R. Folio, Radiology and Imaging Sciences, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Liza Lindenberg, Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Mark Raffeld, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Jeffrey Lin, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Min-Jung Lee, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Sunmin Lee, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Sylvia V. Alarcon, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Akira Yuno, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Nancy A. Dawson, Georgetown University, 3800 Reservoir Road Northwest, 1st Floor, Washington, DC 20007 USA

Kimaada Allette, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Arpita Roy, Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Dinuka De Silva, Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA.

Molly M. Lee, Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Tristan M. Sissung, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Center for Cancer Research, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

William D. Figg, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Center for Cancer Research, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Piyush K. Agarwal, Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, Building 10, Center for Cancer Research, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

John J. Wright, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Yangmin M. Ning, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

James L. Gulley, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

William L. Dahut, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Donald P. Bottaro, Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 13N240, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

Jane B. Trepel, Developmental Therapeutics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute Building 10, Magnuson Clinical Center, Room 12C432A, Bethesda, MD 20892 USA

References

- 1.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 4602–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G, et al. Randomized phase II/III trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A, et al. Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 312–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1015–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apolo AB, Infante JR, Balmanoukian A, et al. Avelumab, an Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Antibody, In Patients With Refractory Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results From a Multicenter, Phase Ib Study. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balar AV, Castellano D, O’Donnell PH, et al. First-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 1483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siefker-Radtke A, Necchi A, Park S, et al. First results from the primary analysis population of the phase 2 study of erdafitinib (ERDA; JNJ-42756493) in patients (pts) with metastatic or unresectable urothelial carcinoma (mUC) and FGFR alterations (FGFRalt). J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(15 suppl): abstr 4503. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg JE, O’Donnell PH, Balar AV, et al. Pivotal Trial of Enfortumab Vedotin in Urothelial Carcinoma After Platinum and Anti-Programmed Death 1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 2592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg JE, Ballman K, Halabi S, et al. CALGB 90601 (Alliance): Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing gemcitabine and cisplatin with bevacizumab or placebo in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37(suppl 15): abstr 4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balar AV, Apolo AB, Ostrovnaya I, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 724–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galsky MD, Hahn NM, Powles T, et al. Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, and sunitinib for metastatic urothelial carcinoma and as preoperative therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2013; 11: 175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerullis H, Eimer C, Ecke TH, Georgas E, Arndt C, Otto T. Combined treatment with pazopanib and vinflunine in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma refractory after first-line therapy. Anticancer Drugs 2013; 24: 422–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krege S, Rexer H, vom Dorp F, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind multicentre phase II study comparing gemcitabine and cisplatin plus sorafenib chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin plus placebo in locally advanced and/or metastasized urothelial cancer: SUSE (AUO-AB 31/05). BJU Int 2014; 113: 429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choueri T, Halabi S, Sanford B, et al. Cabozantinib Versus Sunitinib As Initial Targeted Therapy for Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Poor or Intermediate Risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1814–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Muller SP, et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim I, Lindenberg M, Mena E, et al. 18F-Sodium fluoride PET/CT predicts overall survival in patients with advanced genitourinary malignancies treated with cabozantinib and nivolumab with or without ipilimumab. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2019. September 14 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin C, Bradshaw T, Perk T, et al. Repeatability of Quantitative 18F-NaF PET: A Multicenter Study. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folio LR, Turkbey EB, Steinberg SM, Apolo AB. Viable tumor volume: Volume of interest within segmented metastatic lesions, a pilot study of proposed computed tomography response criteria for urothelial cancer. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 1708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athauda G, Giubellino A, Coleman JA, et al. c-Met ectodomain shedding rate correlates with malignant potential. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 4154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apolo AB, Karzai FH, Trepel JB, et al. A Phase II Clinical Trial of TRC105 (Anti-Endoglin Antibody) in Adults With Advanced/Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017; 15: 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 781–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1850–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham TJ, Box G, Tunariu N, et al. Preclinical evaluation of imaging biomarkers for prostate cancer bone metastasis and response to cabozantinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: dju033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haider MT, Hunter KD, Robinson SP, et al. Rapid modification of the bone microenvironment following short-term treatment with Cabozantinib in vivo. Bone 2015; 81: 581–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yavuz S, Apolo AB, Kummar S, et al. Cabozantinib-induced thyroid dysfunction: a review of two ongoing trials for metastatic bladder cancer and sarcoma. Thyroid 2014; 24: 1223–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuo RC, Apolo AB, DiGiovanna JJ, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor cabozantinib. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolaney S, Ziehr D, Guo H, et al. Phase II and Biomarker Study of Cabozantinib in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Oncologist 2017; 22: 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanna RN, Cekic C, Sag D, et al. Patrolling monocytes control tumor metastasis to the lung. Science 2015; 350: 985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen P, Liu K, Hsu P, et al. Induction of immunomodulatory monocytes by human mesenchymal stem cell-derived hepatocyte growth factor through ERK1/2. J Leukoc Biol 2014; 96: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo Y, Askeland E, Newton M, O’Donnell M. Role of IL-10 in Urinary Bladder Carcinoma and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Immunotherapy. Am J Immunol 2012; 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Togashi Y, Shitara K, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression - implications for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019; 16: 356–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.