Abstract

Objectives: A wealth of literature has established risk factors for social isolation among older people; however, much of this research has focused on community-dwelling populations. Relatively little is known about how risk of social isolation is experienced among those living in long-term care (LTC) homes. We conducted a scoping review to identify possible risk factors for social isolation among older adults living in LTC homes. Methods: A systematic search of five online databases retrieved 1535 unique articles. Eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Results: Thematic analyses revealed that possible risk factors exist at three levels: individual (e.g., communication barriers), systems (e.g., location of LTC facility), and structural factors (e.g., discrimination). Discussion: Our review identified several risk factors for social isolation that have been previously documented in literature, in addition to several risks that may be unique to those living in LTC homes. Results highlight several scholarly and practical implications.

Keywords: social isolation, long-term care, older adults, risk factors

Introduction

Social isolation is a growing public health concern that affects many older people and has been declared a global epidemic amongst the older adult population by the US Surgeon General (Murthy, 2017). Globally, up to 50% of older persons over 60 years of age are at risk of experiencing social isolation (Ibrahim et al., 2013; Landeiro et al., 2017). The impacts of social isolation, either for a prolonged period during an individual’s lifespan or for transient periods, can and do have adverse consequences (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015). Studies show that the aging process is associated with heterogeneity and interindividual variability and that those who experience significant loss of capacity are at increased risk of social isolation and loneliness (Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). The heterogeneity among older persons and diversity in their capacities and health needs underscore the importance of a comprehensive, global public-health response to combat social isolation and accompanying mental health issues (World Health Organization, 2015).

Increased social isolation among older adults can be a result of a variety of factors, including family dispersal, loss of loved ones and peers, retirement, decreased mobility and income, and declining health (Cornwell & Waite, 2009; Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Heffner et al., 2011; Steptoe et al., 2013). In a meta-analytic review, Holt-Lunstad et al. (2015) correlated social isolation with lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and high alcohol consumption, both of which are well-established risk factors for premature mortality. A recent study found that high levels of perceived social isolation in older adults were also associated with increased levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Santini et al., 2020). Further, a cross-sectional analysis of data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study found certain segments of the older population to be at a higher risk of social isolation, reporting differences based on sociodemographic factors, including race, income, being 80 or older, a woman, an immigrant, or a member of minority group, and those living with health issues, such as chronic illnesses and disabilities (Cloutier-Fisher et al., 2011; Cudjoe et al., 2020; The National Seniors Council, 2014). Additionally, place of residence, in particular, nursing homes can exacerbate social isolation and loneliness potentially due to increased dependency and a lack of intimate relationships (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2004). Research suggests that there is a complex and bidirectional relationship between social isolation and institutionalization and that social isolation (and loneliness) may directly or indirectly lead to institutionalization in many cases, and vice versa (Brock & O’Sullivan, 1985). In other words, it is likely that some residents of long-term care (LTC) homes were already isolated or at risk of isolation when moving into the institution.

Promoting social integration amongst older people is important for improving their physical and mental health as socialization and social activities are indicators of productive and healthy aging and have been shown to improve cognitive function, independence (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Uchino, 2006), and overall longevity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Shor et al., 2013). In the literature, there are nuances in the discourse on social integration in relation to societal and institutional factors that constrain access to integration. For instance, poor health and low income can act as barriers to participating in social activities and increase isolation and exclusion among older adults. Over the life course, the structure and quality of social relations may be altered by changes in functional capacity (Ajrouch et al., 2001). For this reason, increasing the social integration of older adults is of vital importance as it can alleviate the devastating sense of isolation and loneliness and improve the quality of life of older adults (Cattan et al., 2005).

As the global population continues to rise, the number of older persons is projected to double to 1.5 billion by 2050, representing 16% of the world population (United Nations, 2019). The “demographic imperative” of a progressively aging society places unprecedented demands on healthcare systems across the globe, their workforce, and budgets. In particular, there will be greater demand for LTC homes to accommodate subpopulations of older people who have, or are at high risk of, significant losses in capacity and those with complex health and social needs (United Nations, 2015). Evidence suggests however that the current health services, including LTC facilities, are not adequately aligned to meet the needs of aging populations nor do they provide age-appropriate integrated care services that focus on maintaining the intrinsic capacity (e.g., physical and mental health functioning) of older persons (DeSalvo et al., 2009; Grenade & Boldy, 2008; WHO, 2015) and that many of these facilities fall short of providing quality care, sufficient activities, and stimuli, including individualized care and services and recreational support, for residents. In such settings, residents often lack meaningful engagement, the necessary stimulation, and social interactions/relationships, predisposing them to loneliness and isolation (Abbott et al., 2015). The radical change in the age composition of the current population suggests the need to reform LTC policies to ensure better access to high quality care to improve the quality of life for older adults (Wagner et al., 2012).

Social Isolation Versus Loneliness

In the scientific literature, social isolation and loneliness are generally considered to be distinct, although closely interrelated, concepts (Grenade & Boldy, 2008); however, the terms are often wrongly used interchangeably. Although there is a great deal of inconsistency in defining or measuring social isolation (e.g., Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Valtorta et al., 2016), the concept is typically defined as an objective measure that is reflected by the number of social contacts or relationships an individual has (Gierveld & Tilburg, 2006). In contrast, loneliness is defined as a subjective feeling that arises from a lack in the quantity or quality of one’s social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Owing to the fact that the two concepts are interrelated, identifying the risk and protective factors specific to each is challenging (Grenade & Boldy, 2008) as many of the same factors are associated with both. In addition, there continues to be a lack of consistency in the ways in which the concepts are operationalized (Grenade & Boldy, 2008), which limits the ability to meaningful comparisons between concepts. However, it is important to distinguish between the concepts as one can occur without the other (Perlman, 2004). For the purposes of this review, we will focus mainly on the risk factors for social isolation in older adults in LTC facilities as less is known about the extent of isolation in residential settings.

Research Gap

Despite decades of research on social isolation, most studies on the risk factors of social isolation in the older adult population have focused primarily on community-dwelling seniors with limited attention on seniors residing in LTC facilities (Grenade & Boldy, 2008). The lack of research on social isolation in the context of LTC facilities could be due to the common assumption that older people in LTC settings are less likely to experience social isolation due to its environment, which allows for physical proximity to others through amenities such as communal areas and on-site care (Grenade & Boldy, 2008; McKee et al., 1999). Given the rise in social isolation among older persons, exacerbated by the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the unique characteristics of the LTC environment, and the paucity of research in this area, this scoping review was designed to address this gap.

The Review

Aim

The main objective of this scoping review is to synthesize the best available evidence on the risk factors contributing to social isolation amongst older adults in LTC settings. Understanding the factors associated with social isolation will contribute to developing targeted interventions to address social isolation and strengthen social engagement among residents, families, and care providers and ultimately improve the mental health and quality of life of older people.

Methods

Design

The design of this scoping study was based on the seminal work of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) methodology for reviews and enhancements to this work by Levac et al. (2010). As such, this protocol is organized into five stages, expanded upon below.

Stage 1: identifying the research question(s)

The first stage, according to Arksey and O’Malley (2005), involves a generalist question and key terms to “generate breadth of coverage.” As the aim of this review was to portray an extensive scope of literature pertaining to social isolation, this review was guided by the following interrelated query: What are the risk factors for social isolation among older adults in residential LTC? To address this question, we extracted the risk factors for social isolation as reported in each of the included studies. Key concepts within our research question include “social isolation,” “older adults,” and “LTC” (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Search Terms.

| Concepts | Terms |

|---|---|

| Older adults | Aged |

| Older adulta | |

| Seniora | |

| Elderlya | |

| Eldera | |

| Older persona | |

| Older people | |

| Long-term care | Long-term care |

| Long-term residence | |

| Long-term facilitya | |

| Nursing homea | |

| Residential care | |

| Residential facilitya | |

| Old aged home | |

| Social isolation | Isolation |

| Lonelya |

Example of search terms used.

Stage 2: identifying relevant literature

Several preliminary scoping searches were conducted with the intent to gain familiarity with the literature and aid with the identification of keywords, followed by a comprehensive search in five major health bibliographic databases (AgeLine, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, Ovid, and PsychINFO). An academic health sciences librarian at the university with years of experience working in the field was consulted to develop the search strategy and execute the searches. Publications included in this review were limited to English language articles published between 1990 and July 2020. The search strategy was developed to identify studies on social isolation for older people, but the strategy was tailored to the risk factors of social isolation among seniors in residential LTC homes.

Stage 3: study selection

The selection of studies for inclusion as well as the exclusion criteria were developed iteratively, as recommended by Levac et al. (2010). Reviewers met throughout the review process to discuss and refine the search strategy, as required. We used Covidence online software (https://www.covidence.org/), the standard platform for Cochrane Reviews, to manage study selection. The study selection process involved three interrelated steps: abstract reviews, full-article reviews, and reviewers’ examination of reference lists from full articles to identify articles for possible inclusion.

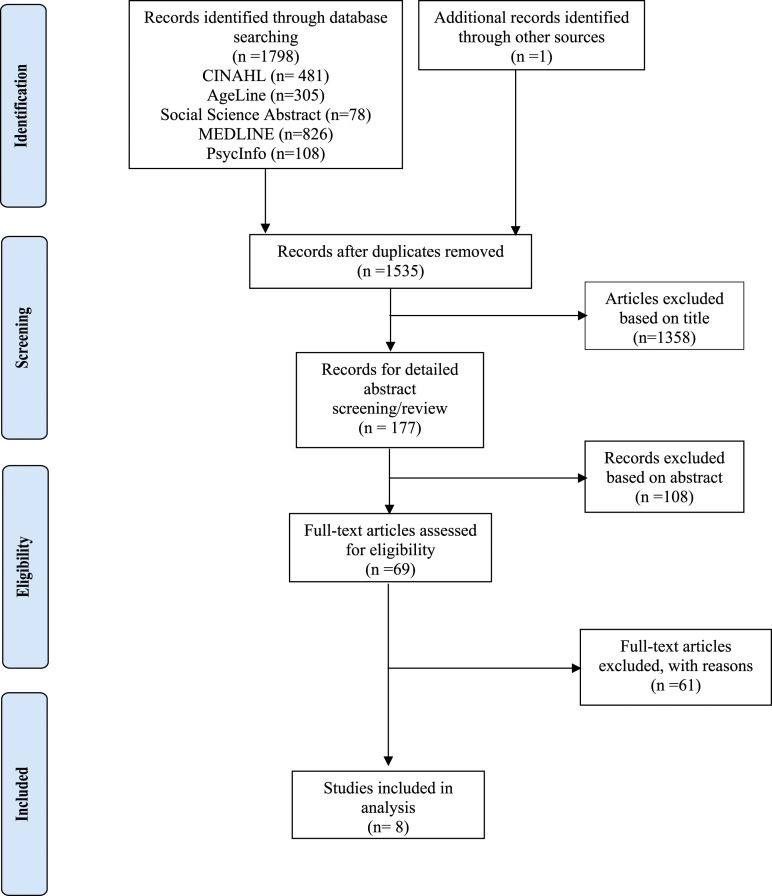

In the initial phase of the search, two of the team members were randomly assigned to review the 768 article titles and abstracts independently. Relevant abstracts were entered into Covidence for each team member to review and indicate “Yes” or “No” depending on whether the abstract met the inclusion criteria. When a discrepancy occurred between reviewers, a separate team member was designated as the arbitrator for discrepancies. In Covidence, once both randomly assigned reviewers marked an abstract as “Yes” for inclusion, the paper automatically moved to the full-article review list for the research team to perform a complete review of the articles (n = 69). In the second phase of study selection, all four team members were randomly assigned a set of articles for full review (approximately 17 articles per reviewer) using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the third and final phase, we reviewed the article reference lists for additional and/or potentially relevant articles, but none were added. All discrepancies on final article selection and data extraction were arbitrated in a Zoom meeting with all team members. Study selection was reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). The selection process is illustrated in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA chart. Source: Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., and The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), article: e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Stage 4: charting the data

Data were extracted from the full-text journal articles by one author (SB) using descriptive analytical techniques (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010) in ATLAS.ti 8 based on the aforementioned inclusion criteria and cross-checked by the remaining authors (RW, TL, and NT) for accuracy. Data extraction form was iteratively developed by all the authors throughout data charting to ensure the data extracted reflected the theme of the scoping review. For each included article, we charted by author(s), publication details, study aim and design, sample/size, and methodology (selected data are reported in Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Citation | Location | Aim of Study | Study Design | Sample Size | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckley and McCarthy (2009) | Urban LTC facility in Southern Ireland | To explore residents’ relationships with others | Qualitative phenomenological design | n = 10 (females between 71 and 99 years old) | Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Relations between residents were not intimate Residents replaced certain relationships with other relationships (e.g., friends with family) Visitors connected residents with the outside world Cognitively intact residents did not want to interact with cognitively impaired residents Staffs’ ability to understand residents’ needs enhanced residents’ connectedness Residents felt cut off from the outside world |

| Casey et al. (2016) | Nursing home in Sydney, Australia | To describe nursing home resident’s perceptions of their friendship networks | Multiple social network analysis methods (cross-sectional interviews, standardized assessment, and observation and network analyses) utilized | n = 94 (older adults between the ages of 63 and 94 years) | Observational data on residents’ social interactions. Residents interviewed and verbal and nonverbal responses recorded | Approximately 90% of residents took part in at least one type of structured social activity Residents had sparse networks with unit coresidents and cited age and gender as a barrier to forming friendships with other residents Residents had few nonfamily network members, leading to risk of social isolation |

| Cook et al. (2006) | United Kingdom | To understand the difficulties that residents with sensory impairments face when interacting with others | Study A: hermeneutic inquiry Study B: constructivist study |

Study n = 8 (older adults between 52 and 95 years.) Study B: n = 18 (seniors 70+ years) |

Study A: interviews Study B: Semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and resident focus group interviews |

Being capable of hearing conversations between others let residents feel as though they were part of the outside world. Hearing-impaired residents miss out on this When patients accommodated each other’s problems, they became more familiar Residents with sensory impairments had difficulty recognizing others that they had previously met; their lack of acknowledgment was sometimes viewed as rudeness |

| Grenade and Boldy (2008) | Australia | Identified research gaps on social isolation in residential homes | N/A | N/A | N/A | In the community, a large proportion of older adults experience some degree of loneliness with sociodemographic, health, and life events acting as risk factors Little is known about loneliness and social isolation in nursing homes; some evidence suggests that residents still experience loneliness In residential care, poor health, frailty, diminished cognitive capacity, and dependency act as risk factors for social isolation In residential care, potential interventions include organized activities and events that help residents stay connected with the wider community |

| Kortes-Miller et al. (2018) | Ontario, Canada | To examine LGBTQ2S+ adults’ perspectives on their future in LTCs | Qualitative analysis—focus groups | n = 23 (older adults aged 57–78 years) | Focus groups lasted 1.5 hrs. Audio recordings and transcriptions kept from the focus groups | Participants were concerned about stigmatization and discrimination Participants were worried about being void of social support, losing autonomy, and being dependent on care providers Feared that other residents would be judgmental and that the environment might not be supportive of their identity |

| Ludlow et al. (2018) | Australia, United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan | To determine the effect of hearing loss on person-centered care in LTCs | Two-stage narrative review | n = 6 (publications) | Systematic approach was employed | Environmental factors and cognitive impairment impeded communication for those with hearing loss Hearing loss limited residents’ abilities to participate in social activities LTC did not have adequate onsite services and assisted listening devices Care staff received little information and training on ways to improve communication for hearing-impaired residents but still tried to enhance communication |

| Parmenter et al. (2012) | Rural New South Wales, Australia | To identify determinants of rural nursing home visits | Survey | n = 257 (seniors 65+ years) | Structured telephone surveys | Longer amount of time spent living in a LTC was associated with a decline in the number of visitors Common barriers to frequent visiting included time, distance, and transport problems |

| Webber et al. (2014) | Victoria, Australia | To explore the experience of older adults with intellectual disabilities in LTCs | Dimensional analysis | n = 10 (7 males and 3 females) | Group home staff, LTC staff, and family were interviewed about residents | Other residents were uncomfortable with residents with intellectual disabilities and avoided them Residents with intellectual disabilities preferred interacting with staff to other residents and experienced a disconnection from past relationships Intellectually disabled residents’ health improved |

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The final stage involves analysis of the data charted, reporting of results, and determining the implications of findings, which was a collaborative process among all authors. The results are reported as a narrative summary of study findings. We begin by describing the type of studies included, followed by a thematic analysis, and conclude with a discussion of the implications of our analysis.

Results

The electronic searches conducted in July 2020 yielded 1798 potentially relevant citations. After deduplication and relevance screening, 177 citations met the eligibility criteria based on title and abstract, and the corresponding full-text articles were procured for review (Phase 1 screening). The abstracts underwent title review followed by detailed abstract review, after which 69 were selected for full-text review (Phase 2 screening). After data characterization of the full-text articles, eight scoping reviews remained and were included in the analysis (see Figure 1).

Quality Assessment

Due to the limited number of relevant articles, we did not assess the methodological quality of individual studies as it is not a priority in scoping reviews or part of the scoping review methodology (Peterson et al., 2017). However, some claim formal assessment should be incorporated in the methodology (Daudt et al., 2013) as assessing study quality will enable us to address not only quantitative but also qualitative gaps in the literature (Levac et al., 2010). Being aware of the Arksey and O’Malley’s framework’s inability to provide for an assessment of the quality of the literature (Daudt et al., 2013), our research team is conducting this scoping review as the basis for our next stage of research and will take measures to address this concern in future studies, including using validated instruments.

Thematic analysis

Data were analyzed from an extensive assessment of the eight studies and categorized into three broad themes: (1) individual factors (issues at the level of the individual patient that predispose residents to isolation), (2) system factors (factors stemming from the healthcare system/LTC and its structure), and (3) structural factors (factors that are embedded within and systematically produced by historical, political, social, or economic structures).

Theme 1: Individual Factors

Individual factors relate to issues at the level of the individual resident that predispose them to social isolation, including communication barriers and cognitive impairment. Inability to effectively communicate one’s thought was noted as a key risk factor for experiencing and becoming socially isolated (Casey et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2006; Grenade & Boldy, 2008; Ludlow et al., 2018). Six of the eight publications reported the effects of poor communication between fellow residents and/or healthcare providers, as a barrier to residents’ engagement and participation in social activities. Communication breakdown as a result of sensory deficits including hearing loss was noted in various degrees in all of the eight articles reviewed. Grenade and Boldy (2008) reported “loneliness and/or isolation to be associated with sensory impairments (e.g., hearing loss) and physical disabilities” (p. 471). Ludlow et al. (2018) noted similar concerns but this time focused on the physical environment in the LTC homes and concluded that the environment in the home often makes it challenging to those with sensory deficits and can create communication breakdown for residents experiencing hearing loss. Background noise from the environment and surroundings can reduce residents’ abilities to hear others and engage in conversation and “participation in the life of the aged care facilities” (Ludlow et al., 2018, p. 300). The inability to effectively communicate thoughts left many residents struggling to make meaningful connections with fellow residents, depriving them of opportunities to make meaningful friendships. The concept of friendship and positive network within the care home was especially important to residents. Casey et al. (2016) reported that impaired communication ability to approach or avoid others decreased residents’ social functioning and ability to engage in casual conversations and have positive interactions that may lead to relationship building.

Another individual factor reported in almost all of the articles was the role of cognition in social engagement. Cognitive impairment was commonly reported as a factor resulting in social isolation among LTC residents, especially for residents living with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Studies have shown longitudinal associations between cognitive decline and social isolation and vice versa (Evans et al., 2019; Read et al., 2020; Thomas, 2011). Impairment in cognition intensifies communication difficulties for residents especially among those with hearing loss as the effects of mishearing information and the inability to fully comprehend became a source of confusion. In our review, Ludlow et al. (2018) reported that “residents with dementia had a higher risk of communication breakdown; cognitive and language difficulties coupled with hearing loss affected residents’ ability to maintain conversation” (p. 299). These statements were frequently echoed in other papers.

Theme 2: System Factors

These are factors stemming from the healthcare/LTC facility and its structure, rather than from an individual or interaction between individuals. System factors include the location of the LTC facility and availability of staff, the types of services provided including individualized care and autonomy of residents, and the interaction between various aspects of the healthcare system. Four of the eight studies supporting theme 2 reported the geographical constraints and challenges of maintaining friendships outside of the LTC facility. The geographical location of the LTC facility, especially those in rural or remote communities presented unique challenges for residents to be closely connected with their friends and family, travel to and from LTC to visit friends, and/or have frequent visitations, which often resulted in residents experiencing social isolation. Another theme that was identified was the lack of integration between LTC and broader community/society. In four of the articles, residents reported losing touch with their existing network after moving into LTC and felt disconnected from the broader community. In a study of Irish LTC residents, Buckley and McCarthy (2009) found that “unfortunately, with admission to a LTC facility, older adults experience difficulty maintaining relationships with friends and feel they have little to exchange with friends who reside in the outside world” (p. 390). The lack of contact with the outside world is concerning because it increases the risk of isolation, loneliness, and associated ill-health effects. In addition to the already shrinking social network, Buckley and McCarthy (2009) also reported that 6 out of 10 residents found it difficult to make friends with other residents even after being in the LTC facility for a number of years and that they relied on visitors to help them keep up to date on social events occurring in the family and within the community. Another article reported that

Most residents would also experience some form of loss following a move into residential care—for example as a result of having to leave their home, family and friends (and pets in many cases), local communities and previous life-styles. (Grenade & Boldy, 2008, p. 472, p. 472)

New residents are often emotionally intertwined in the relationship they had with friends, families, and relatives. Family members also expressed concern about the disconnection from past relationships (Webber et al., 2014). Buckley and McCarthy (2009) explored the perceptions of social connectedness in LTC and reported that residents

expressed feelings of ‘‘homesickness’’ and felt they were more connected to their home and what went on there than they were to the long-term care facility. A dwindling pool of friends and relatives due to old age or illness affected the number of social contacts the residents had. (p. 393)

Staff and resident relationships are particularly important and crucial to residents’ well-being and quality of life. Shortage of nursing and other healthcare staff in LTC facilities was identified as a contributing factor to social isolation and decrease in quality of care/life. The interaction and conversations residents have with staff members gave them a feeling of being equal in the relationship, provided a sense of belonging and authenticated the caring relationship (Buckley & McCarthy, 2009). Attitudes and actions of carers either facilitated or hindered residents’ ability to socially connect with other residents. Buckley and McCarthy (2009) found that residents felt, “having someone who listened to them and with whom they felt at ease promoted communication” (p. 393). Two of the eight studies (Grenade & Boldy, 2008; Kortes-Miller et al., 2018) raised the issue of lack of autonomy including dependence on staff and losing the ability to make choices as having potentially negative impact on residents’ quality of life as it contributed to their experience of isolation in LTC homes. Kortes-Miller et al. (2018) shared similar concerns that when residents who are otherwise able to engage in their own activities of daily living lose their autonomy and become dependent on care providers, and to a greater extent the healthcare system, “they anticipate that the aging process will strip away their capacity for decision-making” (p. 209). In doing so, residents become increasingly vulnerable. The dependence on the health system and providers can negatively affect the residents’ social supports (e.g., family, friends, partners, etc.), and as such, “those who are alone are particularly at risk of having their own quality of life spiral downward” (p. 217).

Theme 3: Structural Factors

Structural factors refer to influences that are embedded within and systematically produced by the historical, social, political, and economic structure of a society (McGibbon, 2016; Navarro, 2007). The socioeconomic and historical conditions of LTC facilities are structures designed by the governments/funding agencies, which to a greater extent contribute to inequities in access to health care and resources for the older adult. Structural factors also include the social and physical characteristics of the LTC home environment (e.g., shared living space, provision of nursing and personal care, social and recreational programme, etc.), as well as the residents in the facility (e.g., mostly older people with complex healthcare needs) which all play an important role in the well-being of the older adult. In this review, we found that when LTC residents have decreased autonomy in outdoor participation and increased dependence on staff, they become increasingly isolated, which negatively impacts their quality of life. One participant was quoted saying that

Moving into an institutional environment, with its rules and routines, where one is dependent on others for care and support, can also have a major impact on a person’s ability to retain a sense of autonomy and control over their lives and/or to express their individuality. This may lead to reduced self-esteem, loss of identity and depression. (Grenade & Boldy, p. 472)

Residents with reduced social networks (e.g., size, composition, and quality of relationships) become increasingly dependent on care staff in the LTC facility, which places them at greater risk of social isolation. Research has shown clear links between socioeconomic status (e.g., poverty, limited resources, and network) and social isolation (Kearns et al., 2015). Older people of lower socioeconomic status are more vulnerable to social isolation due to living situations such as living in an unsafe neighborhood or limited financial means (Andersson, 1998; Kearns et al., 2015). And although LTC residents may have safer living conditions, they are not immune as those with limited means/resources can experience similar stressors and concerns as their counterparts in the community.

Our results showed that lack of opportunities for social engagement and building new relationships contributed significantly to social isolation among older adults in LTC homes. Buckley and McCarthy (2009) reported that cognitively intact residents “felt ‘different’ from residents with diminished mental capacity. If these residents were noisy or disruptive, it further supported the feeling of disconnection” (Buckley & McCarthy, 2009, p. 393). Similar concern was expressed in the study by Casey et al. (2016) on nursing home residents’ perceptions of their friendship networks. The authors reported that, “residents [also] indicated uncertainty and ambiguity in close relationships, describing friendship as ‘difficult’ in the nursing home context and noting barriers to friendship such as language and the fact that others ‘have dementia’” (Casey et al., 2016, p. 860). Our results highlight the struggles that both cognitively intact residents and also those who are living with dementia and other mental health conditions face and their unique risk for becoming socially isolated.

Discrimination was identified as an another risk factor for social isolation among LTC residents. Our review showed that residents who experience discrimination from LTC staff/care providers and healthcare system are more likely to be isolated. In particular, aging LGBTQ2S+ individuals reported experiencing stigma and having unique fears, which are often related to personal safety and discrimination. One participant reported that:

Participant who encountered issues of heterosexist assumptions with a health care practitioner described similar fears. However, this participant also recognized that they may be experiencing even greater discrimination within health systems due to the layering of multiple marginalized social positions. (Kortes-Miller et al., 2018, p. 215, p. 215)

Older LGBTQ2S+ adults were stressed because of fear of being assessed in LTC environments for risks of discrimination and rejection. The residents reported fear of being “forced to silence parts of their identities in order to protect themselves and appease others” (Kortes-Miller et al., 2018, p. 214).

Discussion

This paper presents the results of a scoping review investigating risk factors for social isolation among older adults living in LTC homes. As mentioned, this area of research represents a significant gap in the existing literature on aging and isolation. The bulk of existing research on late life social isolation has focused largely on the experiences of community-dwelling older people (Grenade & Boldy, 2008). Consequently, the results presented in this paper provide a much-needed analysis of the current state of scholarly literature regarding social isolation in LTC. Although very few articles met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review (see Methods), the included eight papers formed a rich dataset from which to identify several insights. Together these insights underscore important implications for both practice and research on social isolation in later life while simultaneously raising critical considerations about LTC more broadly.

The first insight pertains to individual-level risk factors for social isolation. The articles included in this review described several individual-level risk factors of note for older people living in LTC homes including communication barriers, sensory impairment, and cognitive impairment. Within the broader social isolation literature, there exists a wealth of knowledge linking factors at the level of the individual to increased risk of social isolation. However, this literature has tended to emphasize the risk associated with multiple comorbidities, mental health concerns, and the death of loved ones, such as one’s spouse (Cotterell et al., 2018; Nicholson, 2012). Fewer studies have investigated the role of communication barriers and cognitive impairment as risk factors. With respect to sensory deficits, hearing loss and the associated communication challenges have been linked to increased risk of social isolation among older people (Mick et al., 2014), Likewise, poor self-reported vision is a significant predictor of social isolation (Coyle et al., 2017). On the other hand, evidence linking cognitive impairment and isolation risk is mixed (Havens et al., 2004), with studies more often investigating cognitive impairment as an outcome of social isolation rather than a predictor (Holwerda et al., 2014; Lara et al., 2019). Overall, these findings complement and build upon the existing literature by providing preliminary evidence that several individual-level risk factors remain relevant for those who live in LTC facilities. However, it is unclear if and how these risk factors may interact with other risk factors differently within the LTC context. It is our recommendation that future research investigate the potential for these individual-level risk factors to differentially shape risk of isolation among those living in LTC, particularly among individuals who may experience additional risk within LTC home settings (e.g., language barrier and minorities).

The second insight pertains to risk factors for social isolation that exist beyond the individual. Analyses revealed that these risk factors fell into two categories: system factors and structural factors. As with the individual-level risk factors, our findings mirror existing research, but also bring possible LTC-specific risk factors to light. Studies in this review emphasized the potential for aspects of the LTC environment and healthcare system to shape risk of isolation among residents (Buckley & McCarthy, 2009; Grenade & Boldy, 2008; Kortes-Miller et al., 2018). These potential contributing factors included reduced autonomy/increased dependence and the disconnect from existing social connections in the community (e.g., family members or friends not living in the LTC). The described loss of independence is somewhat unique to those living in LTC homes in that community-dwelling older people are unlikely to experience such stripping of autonomy due to institutional procedures and policies. Similarly, while moving to any new home may bring about disconnect from contacts and network members, transitioning into LTC may be particularly isolating due to factors such as geographical location, lack of integration with the wider community, and visiting policies. The preliminary evidence identified in this review suggests a need for research examining these risks and other characteristics of the systems within LTC that may contribute to the isolation of residents. It is especially critical for this future research to consider how system-level factors may disproportionately affect those experiencing other known risk factors (e.g., cognitive impairment and little to no family/social network).

At the structural level, studies in this review identified that few opportunities for connection and discrimination were both important factors in shaping isolation risk, particularly for those who felt different from others (Buckley & McCarthy, 2009; Kortes-Miller et al., 2018). These findings are supported by existing research. While a large portion of the gerontological literature has taken a highly individualized approach to social isolation (Weldrick & Grenier, 2018), studies in recent years have increasingly acknowledged structural and societal factors. In doing so, researchers have begun to uncover mechanisms through which older people may come to be socially isolated due to circumstances beyond themselves and beyond their control. For example, a large study of urban-dwelling older people found that few opportunities for connection, a lack of social cohesion, and age-segregated living all contributed to social isolation risk (Buffel et al., 2015). Discrimination toward certain segments of the population can also give rise to social isolation (Kortes-Miller et al., 2018). This review focused on the experiences of LGBTQ2S+ older adults with social isolation and stigma since no studies that reported on other disadvantaged group’s experiences with social isolation in a LTC setting were found. However, discrimination against other groups, such as those with mental or physical disabilities or those of a lower socioeconomic class (Dobbs et al., 2008; Kemp et al., 2012), can be seen in LTC settings. Thus, it is possible that members of these groups might similarly be more likely to experience social isolation. This idea is substantiated by studies performed among older adults living in the community that suggest that discrimination and marginalization may contribute to the social isolation, particularly among ethnic minorities (Visser & El Fakiri, 2016). However, this research was not conducted in a LTC setting, and as such, additional research is warranted to determine the extent to which this may be the case and under what conditions (Visser & El Fakiri, 2016). The findings of this review are consistent with this work, but also highlight the need for intervention strategies that tackle discrimination and other structural contributors, particularly as they interact and intersect with risk factors at other levels. For many older people experiencing social isolation within LTC homes, it is likely that factors at multiple levels interact and/or compound to create differential risk depending on circumstance and environment. For example, an individual may be healthy, mobile, and otherwise well but experience isolation or risk of isolation upon moving into an institutional environment that is exclusionary or not supportive of their social needs.

These system- and structural-level findings are especially noteworthy given that several are unique to those living in institutional environments or are experienced differently within the context of LTC. In finding that certain relevant risk factors for social isolation stem from operational aspects of LTC systems and environments, this review contributes to a wider narrative shift within the social isolation literature whereby systems and structures increasingly come into focus and under scrutiny. Based on these results, it is recommended that future research critically examine the impacts of LTC systems and operations in contributing to the isolation of residents. It is also recommended that this work emphasize the experiences and voices of residents who may be more likely to experience discrimination. Notably, it could be worthwhile to focus on those of older ages, with physical or cognitive illnesses, and of racial minorities or lower socioeconomic status (Dobbs et al., 2008); as similarly to LGBTQ2S+ older adults, these segments of the population can face discrimination in LTC settings and may therefore have different experiences with social isolation. As demand for LTC beds continues to increase (WHO, 2015), this work will become all the more crucial. Investigations into these important system factors will also begin to address the concerning realities of many LTC facilities that have come to light during the COVID-19 global pandemic (Inzitari et al., 2020).

In addition to contributions to the scholarly literature on social isolation risk, the findings of this scoping review also have practical implications for LTCs and those providing care within LTC. Broadly speaking, the individual- and structural-level themes identified in this review complement the existing evidence on isolation risk. However, several of these findings indicate that there are several risk factors that are unique to those residing in LTCs, such as the loss of independence and social network connections as a result of moving into an institution as described by several studies in this review (Buckley & McCarthy, 2009; Grenade & Boldy, 2008). The discovery of risk factors unique to those living in LTC institutions brings into question the current assessment criteria and tools used to identify those at risk of isolation. Given these findings, it is likely that assessment criteria will require optimization to more accurately monitor and evaluate social isolation among this population. There currently exist many scales used to measure risk and social isolation, and reliability studies have been conducted to aggregate and synthesize various indicators employed across these scales (Cornwell & Waite, 2009). These scales have not been tested for reliability within LTC populations, however. Indeed, many of the scales currently used by practitioners include elements of social disconnectedness, often defined in terms of physical separation from other people (Cornwell & Waite, 2009). As older people living in LTC are in essence surrounded by other people, scales that employ this type of criteria will be biased and theoretically less sensitive to identifying isolation among these individuals. Together, these developments provide strong justification for the development of LTC-specific assessment criteria. In a similar vein, the findings from this review suggest a need to revisit current approaches to isolation interventions and prevention strategies within LTC settings that address these unique contributing factors.

The results of the scoping review also raise several critical questions about the planning and operation of modern LTC homes. By and large, the studies included in this review paint a picture of LTC institutions that is less than favorable. Particularly with respect to structural and system-level risks, studies indicated that the social ecosystems within LTCs are not always conducive to strong social integration among residents. Findings underscore problematic patterns related to discrimination and stigmatization, as well as a myriad of social barriers experienced by those with sensory impairments. This theme justifies a reenvisioning of LTC practices currently in place. Specifically, policymakers and other stakeholders are urged to consider how LTC facilities may be better oriented to promote social connection within the institutional environment and to explore means of improving the integration of LTC institutions themselves within the wider community. While the studies in this scoping review were published prior to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the recommendations stemming from this review are more applicable and time-sensitive than ever. Physical distancing and visiting policies, alongside high infection rates, within many LTC homes have compounded to create highly disconnected and isolating environments for many residents (Simard & Volicer, 2020). As these recent policy changes and associated ripple effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to extend well into the next several years, it is paramount that LTC homes consider policies and tactics to maximize social integration among residents where possible. Implementing strategies that promote social integration amongst residents, and indeed with the broader community, will continue to be of great importance if preventing social isolation and associated outcomes is a priority for those operating LTC homes.

Our scoping review was limited by the sparse existence of work on social isolation within the contexts of LTC. While conducting the database searches and subsequent hand searching, the research team identified dozens of articles mentioning social isolation within LTC homes; however, this was seldom framed as a focus within these papers. While this dearth of evidence led to a small (n = 8) number of papers meeting our inclusion criteria, it also provides a strong rationale for this review. The relatively limited availability of evidence in this domain indicates that there is a great need for additional research. Previous scoping reviews of marginalized subgroups of older people have also uncovered a scarcity of research (e.g., Chamberlain et al., 2018) and have published findings based on small samples of studies in order to bring much-needed attention to under-researched phenomena. It is our position that publishing these findings regardless of sample size will serve to spur future research in an underdeveloped area.

Conclusion

This scoping review maps the limited literature on risks for social isolation among older people living in LTC facilities. The findings address a significant knowledge gap and provide a timely overview of the documented risk factors for this population. It remains clear, however, that relatively little is known about the experiences of older, socially isolated people in LTC settings and other residential aged care facilities. Altogether, it is recommended that future research should consider further investigation on the experiences of social isolation among older people living in LTC homes. Specifically, we recommend studies of risk factors identified at all three levels (e.g., individual, systems, and structural) in order to uncover the possible risks which may operate at these levels. Investigations into risk factors are also urged to consider taking into account recent policies implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While certain policies (e.g., restricted visiting and eating meals alone) have served to slow disease spread, it is likely that they have contributed to an increase in social isolation and loneliness among residents. Researchers are also urged to revisit current approaches to isolation measurement and/or identification within LTC homes as some risk factors may be unique to these settings. Additionally, continued efforts are needed to further scrutinize the operation of LTC homes more broadly and consider avenues through which LTC policies and practices may disadvantage some residents more than others. Overall, any future research into these possible risk factors and methods of intervening/preventing isolation within LTC homes will create valuable contributions to a scarce body of research.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: SB conceptualized the study, contributed to the analysis of the literature, wrote the methods, drafted the results, and substantively edited the manuscript. RW contributed to the analysis of the literature, developed the discussion and conclusion, and critically edited the manuscript. JL conducted the literature search and analysis, assisted with the introduction, and developed the table summarizing the studies. NT assisted with article screening, contributed to the writing of the introduction, developed the decision tree, and organized the references.

Declarations of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: 2020 Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Explore—Major Collaborative Project Seed Grant.

ORCID iD

Sheila A. Boamah https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6459-4416

References

- Abbott K. M., Bettger J. P., Hampton K. N., Kohler H.-P. (2015). The feasibility of measuring social networks among older adults in assisted living and dementia special care units. Dementia, 14(2), 199-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch K. J., Antonucci T. C., Janevic M. R. (2001). Social networks among Blacks and Whites: The interaction between race and age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(2), S112-S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L. (1998). Loneliness research and interventions: A review of the literature. Aging & Mental Health, 2(4), 264-274. doi: 10.1080/13607869856506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health . (2004). Social isolation among seniors: An emerging issue. Report of the British Columbia Ministry of Health. March, 46. http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2004/Social_Isolation_Among_Seniors.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Brock A. M., O’Sullivan P. (1985). A study to determine what variables predict institutionalization of elderly people. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 10(6), 533-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley C., McCarthy G. (2009). An exploration of social connectedness as perceived by older adults in a long-term care setting in Ireland. Geriatric Nursing, 30(6), 390-396. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffel T., Rémillard-Boilard S., Phillipson C. (2015). Social isolation among older people in urban areas. http://www.micra.manchester.ac.uk/connect/news/headline-430995-en.htm [Google Scholar]

- Casey A.-N. S., Low L.-F., Jeon Y.-H., Brodaty H. (2016). Residents perceptions of friendship and positive social networks within a nursing home. The Gerontologist, 56(5), 855-867. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattan M., White M., Bond J., Learmouth A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing and Society, 25(1), 41‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S., Baik S., Estabrooks C. (2018). Going it alone: A scoping review of unbefriended older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 37(1), 1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0714980817000563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier-Fisher D., Kobayashi K., Smith A. (2011). The subjective dimension of social isolation: A qualitative investigation of older adults’ experiences in small social support networks. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(4), 407-414. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook G., Brown-Wilson C., Forte D. (2006). The impact of sensory impairment on social interaction between residents in care homes. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 1(4), 216-224. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2006.00034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell E. Y., Waite L. J. (2009). Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(Supplement 1), i38-i46. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell N., Buffel T., Phillipson C. (2018). Preventing social isolation in older people. Maturitas, 113(April), 80-84. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtin E., Knapp M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799-812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle C. E., Steinman B. A., Chen J. (2017). Visual acuity and self-reported vision status: Their associations with social isolation in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 29(1), 128-148. doi: 10.1177/0898264315624909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudjoe T. K. M., Roth D. L., Szanton S. L., Wolff J. L., Boyd C. M., Thorpe R. J. (2020). The epidemiology of social isolation: National health and aging trends study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(1), 107-113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt H. M., van Mossel C., Scott S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo K. B., Jones T. M., Peabody J., McDonald J., Fihn S., Fan V., He J., Muntner P. (2009). Health care expenditure prediction with a single item, self-rated health measure. Medical Care, 47(4), 440-447. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190b716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D., Eckert J. K., Rubinstein B., Keimig L., Clark L., Frankowski A. C., Zimmerman S. (2008). An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist, 48(4), 517-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans I. E. M., Martyr A., Collins R., Brayne C., Clare L. (2019). Social isolation and cognitive function in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 70(s1), S119-S144. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierveld J. D. J., Tilburg T. V. (2006). A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging, 28(5), 582-598. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grenade L., Boldy D. (2008). Social isolation and loneliness among older people: Issues and future challenges in community and residential settings. Australian Health Review, 32(3), 468-478. doi: 10.1071/ah080468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens B., Hall M., Sylvestre G., Jivan T. (2004). Social isolation and loneliness: Differences between older rural and urban Manitobans. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 23(2), 129-140. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Capitanio J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner K. L., Waring M. E., Roberts M. B., Eaton C. B., Gramling R. (2011). Social isolation, C-reactive protein, and coronary heart disease mortality among community-dwelling adults. Social Science & Medicine, 72(9), 1482-1488. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., Baker M., Harris T., Stephenson D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., Layton J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic Review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda T. J., Deeg D. J. H., Beekman A. T. F., van Tilburg T. G., Stek M. L., Jonker C., Schoevers R. A. (2014). Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the Amsterdam study of the elderly (AMSTEL). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 85(2), 135-142. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim R., Abolfathi Momtaz Y., Hamid T. A. (2013). Social isolation in older Malaysians: Prevalence and risk factors. Psychogeriatrics: the Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 13(2), 71-79. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzitari M., Risco E., Cesari M., Buurman B. M., Kuluski K., Davey V., Bennett L., Varela J., Prvu Bettger J. (2020). Nursing homes and long term care after COVID-19: A new ERA? The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 24, 1042-1046. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1447-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns A., Whitley E., Tannahill C., Ellaway A. (2015). Loneliness, social relations and health and well-being in deprived communities. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(3), 332-344. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.940354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Hollingsworth C., Perkins M. M. (2012). Strangers and friends: Residents’ social careers in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(4), 491-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortes-Miller K., Boulé J., Wilson K., Stinchcombe A. (2018). Dying in long-term care: Perspectives from sexual and gender minority older adults about their fears and hopes for end of life. Journal of Social Work in End-of-life & Palliative Care, 14(2/3), 209-224. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2018.1487364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeiro F., Barrows P., Nuttall Musson E., Gray A. M., Leal J. (2017). Reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 7, Article e013778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara E., Caballero F. F., Rico‐Uribe L. A., Olaya B., Haro J. M., Ayuso‐Mateos J. L., Miret M. (2019). Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(11), 1613-1622. doi: 10.1002/gps.5174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow K., Mumford V., Makeham M., Braithwaite J., Greenfield D. (2018). The effects of hearing loss on person-centred care in residential aged care: A narrative review. Geriatric Nursing, 39(3), 296-302. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGibbon E. (2016). Oppressions and access to health care: Deepening the conversation. In Raphael D. (Ed.), Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives (3rd ed., pp. 491-520). Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mckee K. J., Harrison G., Lee K. (1999). Activity, friendships and wellbeing in residential settings for older people. Aging & Mental Health, 3(2), 143-152. doi: 10.1080/13607869956307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mick P., Kawachi I., Lin F. R. (2014). The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 150(3), 378-384. doi: 10.1177/0194599813518021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L. A., PRISMA-P Group . (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy V. (2017, September 26). Work and the loneliness epidemic. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/09/work-and-the-loneliness-epidemic [Google Scholar]

- National Seniors Council . (2014). Report on the social isolation of seniors 2013-2014 (issue october). https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/nsc-cna/documents/pdf/policy-and-program-development/publications-reports/2014/Report_on_the_Social_Isolation_of_Seniors.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V. (2007). What is a national health policy? International Journal of Health Services, 37(1), 1-14. doi: 10.2190/H454-7326-6034-1T25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson N. R. (2012). A review of social isolation: An important but underassessed condition in older adults. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 33(2-3), 137-152. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter G., Cruickshank M., Hussain R. (2012). The social lives of rural Australian nursing home residents. Ageing and Society, 32(2), 329-353. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11000304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau L. A., Perlman D. (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman D.. (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 23(2), 181-188. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J., Pearce P. F., Ferguson L. A., Langford C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(1), 12-16. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read S., Comas-Herrera A., Grundy E. (2020). Social isolation and memory decline in later-life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(2), 367-376. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini Z. I., Jose P. E., York Cornwell E., Koyanagi A., Nielsen L., Hinrichsen C., Meilstrup C., Madsen K. R., Koushede V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62-e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E., Roelfs D. J., Yogev T. (2013). The strength of family ties: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Social Networks, 35(4), 626-638. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simard J., Volicer L. (2020). Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 966-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Shankar A., Demakakos P., Wardle J. (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797-5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. A. (2011). Gender, social engagement, and limitations in late life. Social Science & Medicine, 73(9), 1428-1435. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377-387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2015). World population ageing 2015. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2019). Department of economic and social affairs, population division. World population ageing 2019 highlights. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta N. K., Kanaan M., Gilbody S., Hanratty B. (2016). Loneliness, social isolation, and social relationships: What are we measuring? A novel framework for classifying and comparing tools. BMJ Open, 6, e010799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M. A., El Fakiri F. (2016). The prevalence and impact of risk factors for ethnic differences in loneliness. European Journal of Public Health, 26(6), 977-983. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner L. M., McDonald S. M., Castle N. G. (2012). Joint commission accreditation and quality measures in U.S. nursing homes. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 13(1), 8-16. doi: 10.1177/1527154412443990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber R., Bowers B., Bigby C. (2014). Residential aged care for people with intellectual disability: A matter of perspective: Residential aged care for people with ID. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 33(4), E36-E40. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldrick R., Grenier A. (2018). Social isolation in later life: Extending the conversation. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 37(1), 76-83. doi: 10.1017/S071498081700054X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2015). World report on ageing and health. Geneva: WHO. ISBN: 9789241565042. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]