Abstract

Nurses may experience cumulative sleep deprivation in the current epidemiological situation, which is the COVID-19 disease. Lack of rest leads to decreased concentration. The research topic is important for improving patient safety in hospitals. Assessment and analysis of the level of sleepiness of nurses after 3 consecutive night shifts and its impact on functioning in social life. The study adopted the diagnostic survey method, which was conducted using a survey technique. The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: personal particulars, the survey and the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) version A. After the research, 164 correctly completed questionnaires were obtained. The level of somnolence in individual measurements after a night shift significantly increased among the nurses examined (P < .0001). Respondents who felt a higher level of drowsiness after a night shift thought that their work definitely influenced contact with their friends or family and had difficulty in performing household duties. There is no statistically significant relationship between the level of sleepiness and sociodemographic factors. After each night shift, the level of drowsiness in nurses increases. This may result in reduced alertness and attention levels on subsequent working days. Shift work has negative consequences in the form of depleted personal life. Further research into the effects of insufficient sleep among nurses should be conducted. This may be necessary for patient safety in healthcare centers. The awareness on the subject of healthy sleep among shift nurses should be raised. It is advisable to conduct research in order to assess the effectiveness of various therapies in dealing with sleep disorders among shift nurses. The interventions taken should be adapted to the current epidemiological situation, which is the COVID-19 disease.

Keywords: fatigue, insomnia, nurses, shift work, sleepiness, COVID-19

What do we already know about this topic?

Nurses may experience cumulative sleep deprivation in the current epidemiological situation, which is the COVID-19 disease.

How does your research contribute to the field?

The research topic is important for improving patient safety in hospitals.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

It is important to raise the awareness of the issue of healthy sleep among shift nurses. It is advisable to conduct rigorous intervention study to assess the efficiency of various therapies in dealing with sleep disorders of shift nurses. In the research the psycho-social and biological differences should be taken into consideration in order to ensure interventions appropriate for the needs of every nurse.

Introduction

A new threat to humanity in the form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, for which, from January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced an international public health threat in the form of the COVID-19 disease, disrupting the work of medical service employees. 1 Many COVID-19 patients are critically ill and require intensive care. Treating these patients exposes healthcare professionals to difficult tasks that require repetitive, difficult activities and a high level of care. The stress caused in such cases increases the risk of physical and mental disorders of medical personnel. 2 Nurses in Poland have been overloaded with work, which causes them to develop somatic complaints due to lack of sleep and fatigue. 3 Sleep is a basic need of every human being. Without sleep, it is impossible for the body to function properly and maintain homeostasis. 4

The circadian rhythm determines the physical and mental fitness of a person throughout the day and what time of sleep is the most favorable for him. It is easier for a nurse with a regular circadian rhythm to achieve good results at work. Disturbances in the circadian rhythm disturb the harmony of the body. A person begins to feel worse and worse, and with time, other health problems add to the mental malaise. The circadian rhythm is regulated by a special anatomical structure in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nuclei or the biological clock. It measures time inside the body and influences human functioning throughout the day. 5

The daily demand for sleep may vary from person to person depending on gender, age, and type of work performed. On average, a person needs about 8 h of sleep a day. 6 Cumulative sleep deprivation occurs among nurses. The average duration of sleep among nurses is 5.5 h. Their sleep is often shallow and poor quality. 7 Many endogenous and exogenous factors affect the fulfilment of the need to sleep. Environmental factors affect the quality of sleep and the feeling of drowsiness. Irregularities related to the lack of sleep hygiene include having a job which goes against the natural sleep-awake rhythm. 8 It has been proved that night shifts can lead to sleep disorders as well as digestive and cardiovascular disorders. Shift work can lead to dysfunctions of the immune system and even psychiatric disorders such as neurotic disorders. 9 The shift work system is the dominant mode of work in healthcare facilities. Most often these are 12-h shifts. 10 This mode of work results in somatic disorders caused by fatigue, desynchronization of circadian rhythms, stress and hinders the fundamental need to perform social roles and functions. 11 Shift work can lead to negative effects on the physiological and mental health of people. This can negatively affect the safety of both employees and patients. 12 The nursing staff who work in a shift system experience problems in 4 main areas: increased fatigue and drowsiness due to reduced sleep, deteriorated overall physiological and mental health, family and social problems, quality of work and job satisfaction. These problems are caused by desynchronization of the endogenous physiological circadian rhythm system. 13

Shift work may contribute to the development of cancer diseases. In 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer said there was evidence of an increased risk of cancer in shift workers. Especially in medical personnel suffering from disturbed circadian rhythms.14,15

Shift work may cause interpersonal relationships in micro and macro-communities to become shallow. 16 The conflict between work and family is a type of conflict between roles. 17 Nurses are overloaded with work and experience time pressure. Requirements related to work, such as the number of hours worked, workload, shift work are positively related to the conflict between work and family. 18 Lack of sleep and nurses’ fatigue that affects their relationship with their family can have a negative impact on the delivery of health services. Such a situation may harm the health and life of patients with SARS-CoV-2 virus. 19 This is associated with poor mental health and negative organizational attitudes. The work-family conflict contributes to a lower level of job and life satisfaction. 20

Assessment and analysis of the level of sleepiness of nurses after 3 consecutive night shifts and its impact on functioning in social life. The subject of the study is very important because the literature reports that the incidence of psychosomatic symptoms in nurses during the COVID-19 epidemic is higher than in previous epidemics such as H1N1 influenza and acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS). Maintaining the health of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic is critical to the health of the population.21-25

Method

Organization and Study Group

The study lasted 4 months. It was conducted from December 2019 to April 2020 among female and male nurses of the Fryderyk Chopin Clinical Provincial Hospital No. 1 in Rzeszów in Podkarpackie Province. Podkarpackie Province is located in the southern part of Poland and has population of over 2 million inhabitants, which constitutes 5.5% of Poland’s population. 26 The study was conducted at randomly selected surgical and medical treatment wards. There are 233 012 nurses employed in Poland, including 12 400 in Podkarpackie Province. 27 A written consent of the director of the healthcare facility was obtained. The study was a pilot study and cross-sectional. The studied sample was selected basing on at least 1 factor common to the entire sample which is representative of the general population (work in a shift mode). The sample size was estimated using the Sample Selection Calculator. The assumed fraction size was 0.5 and the maximum error was 5%. The selection for the research sample was a random one. Nurses working in a 12-h shift mode were included in the study. 164 sheets completed according to the instructions were collected. The nurses who had infection, cold or flu at the time of the study were excluded. The characteristics of the study group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Sample Characteristics.

| The sample characteristics | Work experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Women | 94.5% | Upto 5 years | 55.5% |

| Men | 5.5% | 6 to 10 years | 11.6% |

| Place of residence | |||

| Countryside | 50.6% | 11-15 years | 4.3% |

| City | 49.4% | 16-20 years | 9.8% |

| Place of work | |||

| Surgery ward | 50% | 20 years | 18.9% |

| Treatment ward | 50% | ||

The Course of Study

The research is was a longitudinal, correlational study. The study adopted the diagnostic survey method, which was conducted using a survey technique. The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: personal particulars, the survey part and the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) version A. 28 The survey questionnaire consisted of 13 questions. It was focused on examining the respondents’ opinions on the consequences of shift work. The questionnaire included questions about:

- the number of hours spent sleeping after the shift,

- the period of the day devoted to sleep after the night shift,

- relationships with family and friends after shift

- feeling irritable after a night shift

- neglecting household duties

- taking sleeping pills

KSS assessed the level of drowsiness immediately after 3 consecutive night shifts within 8 days. The KSS scale is based on the Likert scale. The respondents rated their level of drowsiness in 5 categories: “extremely sleepy, I fight with sleep,” “sleepy, but I can easily resist drowsiness,” “neither alert nor sleepy,” “alert,” “extremely alert.” 29 The empirical procedure included the criterion of the time when the KSS test should be completed. These were 3 attempts in 3 consecutive days after the overnight shift over the 8 days. The questionnaire survey was not covered by the strict time criterion.

The respondents gave their written consent to participation in the study. To avoid as much as possible any contrasts resulting from the organizational aspects of different facilities that may affect job satisfaction and have a bearing on answers given, the survey was conducted on the premises of a single health facility. The study was completely anonymous. It was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Bioethics Committee.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 2,0, MS Excel, chi-square distribution tables and Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis statistical tests, Spearman rank, V-Cramer, Kendall’s Tau-b statistical tests and 1-way ANOVA variance correlation using mathematical formulas characteristic for these tests were used for statistical calculations. The significance level P < .05 and the number of dependent freedom were adopted for the study of dependence on the number of categories of analyzed variables.

Results

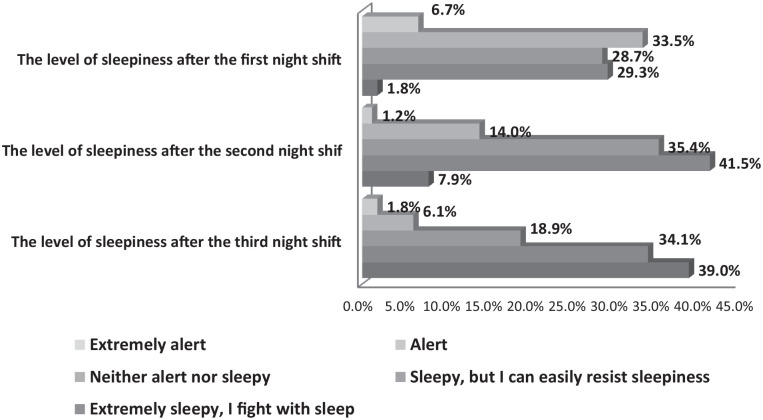

The KSS scale showed that 33.5% of people were alert after the first night shift, 14.0% after the second shift and 6.1% after the third shift. A group of 29.3% of people after the first night shift were drowsy, but easily resisted drowsiness. 1.8% of people felt extremely sleepy. After the second night shift, 41.5% of nurses were drowsy, but resisted drowsiness without difficulty. 7.9% of people were extremely sleepy, struggling to resist falling sleep. After the third night shift, 39% of respondents were extremely sleepy, and 34.1% of respondents felt sleepy, but they were able to resist it (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The level of sleepiness in the next 3 night shifts.

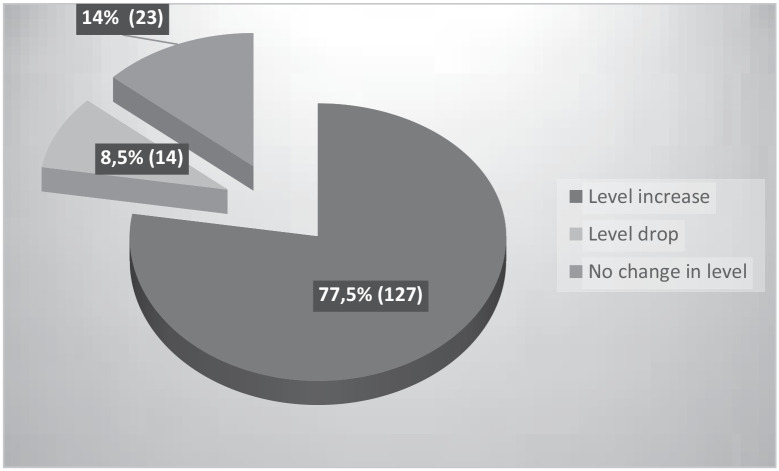

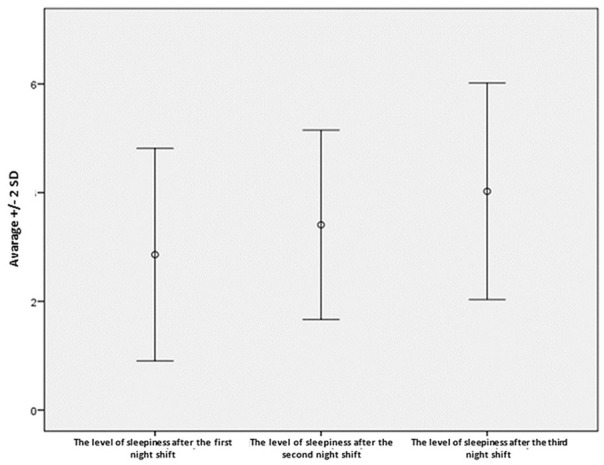

The research showed that the level of drowsiness in individual measurements after a night shift significantly increased among the examined nurses. The differences in the level increase between shift II and shift I were statistically significant (t = -7.41; df = 163; P < .0001). Lower values of the feeling of drowsiness were demonstrated after the first shift than after the second one. It was also found that after the third shift, the level of drowsiness among the respondents was significantly higher than after the second shift, indicating a lower level of drowsiness after the second shift (t = -8.74; df = 163; P < .0001). In order to assess how the respondents’ level of drowsiness varied after consecutive night shifts, the differences in the feeling of drowsiness between the second and first shift, the third and second shift and the third and first shift were examined. The sum of the differences in these 3 cases corresponded to the overall change in the level of drowsiness over 3 shifts. The obtained results ranged between -2 to 4 points. They were divided into 3 groups assessing the change in the level of drowsiness of the respondents:

- decrease in the level of drowsiness over 3 consecutive night shifts (values below 0),

- no change in the level of drowsiness over 3 consecutive night shifts (value equal to 0),

- increase in the level of drowsiness over the last 3 night shifts (values above 0) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in level of sleepiness in the next 3 night shifts.

It was demonstrated that 8.5% of nurses experienced a decrease in the level of drowsiness during 3 consecutive night shifts. In the group of 14.0% of people, the level of drowsiness during 3 consecutive night shifts did not change. The level of drowsiness of most nurses (77.4%) increased after 3 consecutive night shifts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in the level of sleepiness over 3 consecutive night shift.

After the third shift, people with a higher level of drowsiness (P = .0002) had problems falling asleep despite feeling tired. Moreover, people experiencing a higher level of drowsiness after 3 consecutive night shifts had more problems with sleeping (P = .0333).The use of soporific drugs occurred in people with a higher level of drowsiness after I and III shift. The study group admitted that they use sleeping pills to improve the quality of sleep (12.8%). Sleeping pills were not used by 87.2% of the nurses. (Table 2).

Table 2.

The occurrence of sleep problems despite the feeling of fatigue after night and the level of sleepiness.

| The occurrence of sleep problems despite experiencing fatigue after night shift | The level of sleepiness after the first night shift | The level of sleepiness after the second night shift | The level of sleepiness after the third night shift | Changing the level of sleepiness after 3 consecutive night shifts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | ||||

| Average | 2.96 | 3.53 | 4.28 | 1.33 |

| SD | 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 1.18 |

| No | ||||

| Average | 2.75 | 3.27 | 3.72 | 0.97 |

| SD | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 1.10 |

| Altogether | ||||

| Average | 2.86 | 3.41 | 4.02 | 1.16 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| P | .1583 | .0991 | .0002 | .0333 |

| Using sleeping pills | The level of sleepiness after the first night shift | The level of sleepiness after the second night shift | The level of sleepiness after the third night shift | Changing the level of sleepiness after 3 consecutive night shifts |

| Yes | ||||

| Average | 3.24 | 3.76 | 4.57 | 1.33 |

| SD | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 1.11 |

| No | ||||

| Average | 2.80 | 3.36 | 3.94 | 1.14 |

| SD | 0.97 | 0.88 | 1.01 | 1.16 |

| Altogether | ||||

| Average | 2.86 | 3.41 | 4.02 | 1.16 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| P | .0454 | .0646 | .0047 | .6107 |

P = statistical significance coefficient; SD = standard deviation.

The bold entries are statistically significant relationship.

As a result of the research it was found that people experiencing more difficulties in carrying out their household duties after a night shift had a higher level of drowsiness after the first, second and third night shift than people indicating a lower feeling of these difficulties. A slight deviation from this correlation involved people who indicated “definitely not”;

however it was not significant because there were only 2 people in this group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nurses’ relations with family and friends and the level of sleepiness.

| Greater difficulties in performing house hold duties after night shift | The level of sleepiness after the first night shift | The level of sleepiness after the second night shift | The level of sleepiness after the third night shift | Changing the level of sleepiness after 3 consecutive night shifts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely yes | ||||

| Average | 3.13 | 3.57 | 4.32 | 1.19 |

| SD | 1.03 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 1.19 |

| Yes | ||||

| Average | 2.80 | 3.39 | 3.94 | 1.14 |

| SD | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 1.20 |

| There is no difference | ||||

| Average | 2.81 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 1.19 |

| SD | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 1.03 |

| No | ||||

| Average | 2.00 | 2.67 | 3.11 | 1.11 |

| SD | 0.87 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Definitely no | ||||

| Average | 3.50 | 4.50 | 5.00 | 1.50 |

| SD | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.71 |

| Altogether | ||||

| Average | 2.86 | 3.41 | 4.02 | 1.16 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| P | .0251 | .0367 | .0059 | .9829 |

| Assessment of the impact of shift work on shallowing contacts with family and friends | The level of sleepiness after the first night shift | The level of sleepiness after the second night shift | The level of sleepiness after the third night shift | Changing the level of sleepiness after 3 consecutive night shifts |

| Definitely yes | ||||

| Average | 3.11 | 3.70 | 4.44 | 1.33 |

| SD | 1.09 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 1.33 |

| Yes | ||||

| Average | 2.90 | 3.36 | 4.08 | 1.18 |

| SD | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.01 | 1.17 |

| There is no difference | ||||

| Average | 2.82 | 3.36 | 3.86 | 1.04 |

| SD | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.00 |

| No | ||||

| Average | 2.58 | 3.26 | 3.68 | 1.10 |

| SD | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 1.14 |

| Definitely no | ||||

| Average | 3.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 |

| SD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Altogether | ||||

| Average | 2.86 | 3.41 | 4.02 | 1.16 |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| P | .3845 | .1845 | .0236 | .9153 |

P = statistical significance coefficient; SD = standard deviation.

The bold entries are statistically significant relationship.

People who claimed that shift work definitely influence their relationships with family and friends experienced a higher level of drowsiness after the third night shift than the respondents who claimed that night shifts did not affect their family life (Table 3).

The analysis of the research based on Spearman’s rho factor and the significance level of P < .05 demonstrated that people who claimed that shift work definitely influenced their household relationships experienced a significantly higher level of drowsiness after I and II shift than people who indicated a lower impact of shift work on hindering their household relationships. Similarly, the respondents who indicated a higher impact of shift work on the difficulty in contacts with people outside their household felt a higher level of drowsiness in each of the 3 night shifts (Table 4).

Table 4.

The level of sleepiness of the respondents and the declared level of impact of shift work on contacts with household members and with people from outside the household.

| Impact of shift work on hindering contact with family | Impact of shift work on hindering contacts with people from outside the household | |

|---|---|---|

| The level of sleepiness after the first night shift | ||

| rho | 0.173 | 0.226 |

| P | .0266 | .0036 |

| The level of sleepiness after the second night shift | ||

| rho | 0.203 | 0.225 |

| P | .0091 | .0038 |

| The level of sleepiness after the third night shift | ||

| rho | 0.121 | 0.201 |

| P | .1221 | .0099 |

| Changing the level of sleepiness after 3 consecutive night shifts | ||

| rho | −0.078 | −0.054 |

| P | .3200 | .4946 |

P = statistical significance coefficient; rho = Spearman rank correlation.

The bold entries are statistically significant relationship.

A statistical analysis was made to correlate sociodemographic factors with the level of drowsiness. However, the analysis showed that sociodemographic factors such as gender, place of residence, place of work, work experience do not significantly affect the level of drowsiness after 3 consecutive night shifts within 8 days.

Discussion

In accordance with the hypothesis, the respondents declared the highest level of drowsiness after the third consecutive night shift. Geiger-Brown et al examined nurses working 12-h shifts in terms of drowsiness, fatigue, sleep quality and neurobehavioral performance. They found that 45% of nurses had a high level of drowsiness during their work. They also examined that the nurses became more and more sleepy during each consecutive shift. 7 Dorrian et al showed that 36% of nurses reported difficulties in keeping conscious during night duty. The nurses claimed that at the end of the work and during journey home they were the drowsiest and the most physically exhausted. 30 A study by Huang and Zhao 31 reported a 23.6% increase in the prevalence of sleep disturbances in the COVID-19 medical staff, and this was higher than the prevalence of sleep disturbances in other community groups.

Authors of other papers describing the drowsiness of the shift employee have proved that the subjective sense of drowsiness increases during a night shift. Fatigue and drowsiness accumulate during the following days, over which the body has not regenerated.32,33 Geiger-Brown 7 noted in his study that one-third of nurses had the highest levels of fatigue between shifts. This indicates a lack of recovery after the previous shift, at the beginning of the next shift.

Prolonged sleep deprivation can lead to decreased alertness and attention over subsequent working days. The disruption of sleep and the process of sleep leads to a drop in cognitive processes. An evident relationship between all-night insomnia and decreased attention, as well as a fall in the efficiency of cognitive functions was established. During subsequent shifts, nurses need a longer response time and suffer from reduced co-ordination. This affects patient care and safety. 32 Dorrian shows that nurses work for a long time without regular breaks and therefore experience increased fatigue. This increases the incidence of adverse events in healthcare. Less sleep can lead to a higher risk of making a medical error. Also, it has been shown that the chances to perceive the error of another healthcare professional decrease. 30

It has been proved that when healthy people sleep for less than 5 h their cognitive capabilities begin to decline. 34 Several night shifts during the week may cause problems with falling asleep. 35 In the present study, 54.3% of the participants had problems falling asleep despite being tired. This problem intensified over the following night shifts. In another author’s study, similar data can be seen. As many as 58% of nurses frequently experienced problems falling asleep after a night shift. 36 Insomnia and other disorders after night shifts can be caused by long hours of night work, lack of possibility to have a nap while working at night and delay in circadian rhythm. 37 Tsai et al found that nurses suffer from insomnia more often than other healthcare professionals. They concluded that nurses should be encouraged to relax in order to feel at ease and improve their sleep quality. 38 Job burnout and a high level of occupational stress may contribute to insomnia in nurses. 39 Schultz Autogenous Training may be recommended to nurses, which helps to relax the nervous system. The training is based on the use of a neuromuscular relaxation technique. Relaxation exercises are taken from yoga and Zen meditation. Training is able to cure psychosomatic ailments, neuroses, hyperactivity, hormonal and neurological disorders. 40

Jacobson Relaxation Training can also be used with nurses. Jacobson’s training is based on tensing and relaxing individual muscle groups. There is a relationship between muscle tone and the nervous system. The lower the muscle tension, the more beneficial the effect on the nervous system. By getting rid of tension, the body gets rid of anxiety, calms down and calms down. 41

Insomnia among nurses is a dangerous phenomenon which can cause mood disorders. Nurses suffering from insomnia may be particularly susceptible to the aggravation of depressive symptoms. 42 Sleep deprivation among nurses working in a shift system often causes menstrual disorders. Kang et al 43 demonstrated that insomnia was associated with a 3.05-fold increase in the frequency of menstrual irregularities in comparison to the nurses who had no problems falling asleep after a night shift.

In the present study, the nurses experiencing increased level of somnolence usually took sleeping pills. It is confirmed by the fact that despite feeling tired, there are difficulties in falling asleep. 12.8% of respondents admitted to taking such drugs. Similar results were published by Futenma et al In their study, 10% of nurses admitted to taking sleeping pills. Only 1 sleeping pill was used by 6.9% of respondents while 3.1% of nurses took many different sleeping pills. In this study, nurses who took sleeping pills showed a lower quality of life and more frequent depression symptoms than nurses who did not suffer from insomnia. The nurses who took many sleeping pills made medical errors with greater frequency. Futenma et al concluded that the use of numerous sleeping pills is not beneficial for reducing insomnia or for maintaining a better quality of life for nurses working in a shift system. Other measures should be taken to eliminate insomnia. 44

The best-known intervention practices for insomnia focus mainly on exposure to bright light, nap breaks at work and changes in work schedules. There is less emphasis on behavioral interventions. 45 In order to improve the quality of sleep among nurses, taking care of sleep hygiene and ensuring low-stimulation sleep is recommended. Social support and a suitable working environment are extremely important for the quality of sleep. 46 In the present study, it was noticed that people experiencing increased levels of somnolence showed greater difficulties in social functioning than those with lower levels of somnolence. This referred to contacts with family and other people. The nurses experiencing an increased level of sleepiness complained about reduced contact with the family. The present study also demonstrated that there are more difficulties in doing housework among respondents experiencing increased levels of somnolence. Being active at night can be the cause of fatigue in the period when time was usually spent meeting friends, taking care of the family or having simple pleasures. A nurse working in a shift system starts planning how to effectively relax after and before work more frequently. They more often focus on planning how to balance rest with everyday duties, rather than how to organize time spent together with family or friends. 47 Jensen et al showed in their study that 25% of nurses believe that shift work leads to social isolation. Nurses often experienced headaches and mood swings. The main problems of nurses were the lack of willingness to participate in various family activities in their free time and difficulties in falling asleep after a night shift. 36 Shift work contributes to the work-family conflict. Insomnia is one of the factors making this conflict even more aggravated. 48 Kunst et al 49 believe that nurses transfer work-related problems to family, the so-called negative family-to-work spillover. It negatively affects family bonds.

In the present study, no relationship was found between subjective assessment of sleepiness and sociodemographic factors such as gender, place of residence, place of work, work experience. Axelsson et al obtained similar results in his study. He established no difference between gender or age and the level of somnolence. 50 However, in another study Mallon et al demonstrated that women have a higher level of drowsiness than men. It is associated with hormonal changes and a greater tendency towards insomnia in women. 51 In the present study, the study group was not equally divided according to gender. Probably, that is the reason why there was no gender correlation with the KSS scale. Also, In the study by Åkerstedt et al 52 there occurred no dependence of the level of somnolence on factors such as: place of residence, social status, number of children.

Study Limitations

Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) is a subjective scale. KSS is not an objective measurement scale, however, assuming the appropriate measurement error, it offers an opportunity to examine a large group of people. The study did not check which chronic diseases the nurses suffered from. Blood pressure was not checked, and BMI was not calculated. It would be reasonable to check the amount of coffee consumed and the intensity of physical activity during a night shift. It would be advisable to check if there was a nap during a night shift and how long it lasted. A similar study should be carried out taking into account the above limitations.

Conclusions

After each night shift, the level of somnolence among nurses increases. This can cause an accumulation of drowsiness and fatigue, which leads to a decrease in alertness and level of concentration over subsequent days of work. Further research should be conducted on the effects of inadequate sleep among nurses to find a link between fatigue, insomnia and adverse events occurrence in patient care with SARS-CoV-2 virus. This may be necessary for patient safety in healthcare centers. Shift work has negative consequences in the form of depleted personal life. It may be affected by difficulties in falling asleep despite being tired after a night shift. It is important to raise the awareness of the issue of healthy sleep among shift nurses. It is advisable to conduct rigorous intervention study to assess the efficiency of various therapies in dealing with sleep disorders of shift nurses. In the research the psycho-social and biological differences should be taken into consideration in order to ensure interventions appropriate for the needs of every nurse. The interventions taken should be adapted to the current epidemiological situation, which is the COVID-19 disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of all nurses who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JM: contributed to analysis and interpretation; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. KG: contributed to conception and design; drafted manuscript. ZC: contributed to interpretation; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rzeszow

ORCID iD: Julia Martyn  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0564-5871

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0564-5871

References

- 1. Limin Y, Deyu T, Wenjun L. Strategies for vaccine development of COVID-19. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 2020; 36(4):593-604. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.200094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yifan T. Symptom cluster of ICU nurses treating COVID-19 pneumonia patients in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60(1):e48–e53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newby J, Mabry M, Carlisle B, Olson D, Lane B. Reflections on nursing ingenuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurosci Nurs. 2020;52(5):E13-E16. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barshikar S, Bell KR. Sleep disturbance after TBI. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(11):87. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0792-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Mello M, Silva A, Guerreiro R, Silva F, Esteves A. Sleep and COVID-19: considerations about immunity, pathophysiology, and treatment. Sleep Sci. 2020;13(3):199-209. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20200062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miner B, Kryger MH. Sleep in the aging population. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(1):31-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell R, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(2):211-219. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.645752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Burke TA, Franzen PL, Alloy LB. Sleep disturbance and physiological regulation among young adults with prior depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;115:75-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Narciso FV, Barela JA, Aguiar SA, Carvalho AN, Tufik S, de Mello MT. Effects of shift work on the postural and psychomotor performance of night workers. PLoS One. 2016;11(4): e0151609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Books C, Coody LC, Kauffman R, Abraham S. Night shift work and its health effects on nurse. Health Care Manag. 2017;36(4):347-353. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Metzenthin P, Helfricht S, Loerbroks A, et al. A one-item subjective work stress assessment tool is associated with cortisol secretion levels in critical care nurses. Prev Med. 2009;48:462-466. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol. 2014;62:292-301. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, Ghissassi F, Bouvard V. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1065-1066. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70373-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blakeman V, Williams L, Meng Q, Streuli C. Circadian clocks and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18:89. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0743-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caruso C. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39(1):16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. AlAzzam M, AbuAlRub RF, Nazzal AH. The relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among hospital nurses. Nurs Forum. 2017;52(4):278-288. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Hammer LB, Almeida DM. Finding time over time: longitudinal links between employed mothers’ work-family conflict and time profiles. J Fam Psychol. 2017;31(5):604-615. doi: 10.1037/fam0000303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang CX. Survey of sleep disturbances and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306-312. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ghislieri C, Gatti P, Molino M, Cortese CG. Work-family conflict and enrichment in nurses: between job demands, perceived organisational support and work-family backlash. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(1):65-75. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2997-3003. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Magnavita N, Tripepi G, Di Prinzio R. Symptoms in health care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic. A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5218. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Troglio da, Silva F, Barbosa C. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in an intensive care unit (ICU): psychiatric symptoms in healthcare professionals – a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;110:110299. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amra B, Salmasi M, Soltaninejad F, et al. Healthcare workers’ sleep and mood disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak in an Iranian referral center. Sleep Breath. 2021;13:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11325-021-02312-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yi J, Kang L, Li J, Gu J. A key factor for psychosomatic burden of frontline medical staff: occupational pressure during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 590101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Central Statistical Office. Local Data Bank. Population by singular age and sex. Accessed May, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20200806114827/https://rzeszow.stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/rzeszow/pl/defaultstronaopisowa/979/1/1/ludnosc_2018.pdf

- 27. Main Chamber of Nurses and Midwives. Report of the Supreme Chamber of Nurses and Midwives on the number of nurses and midwives registered and employed in 2018. Accessed December, 2018. https://nipip.pl/liczba-pielegniarek-poloznych-zarejestrowanych-zatrudnionych/

- 28. Miley AÅ, Kecklund G, Åkerstedt T. Comparing two versions of the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS). Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2016;14(3):257-260. doi: 10.1007/s41105-016-0048-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Åkerstedt T, Gillberg M. Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual. Int J Neurosci. 1990;52:29-37. doi: 10.3109/00207459008994241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dorrian J, Lamond N, van den Heuvel C, Pincombe J, Rogers AE, Dawson D. A pilot study of the safety implications of Australian nurses’ sleep and work hours. Chronobiol Int. 2006; 23(6):1149-1163. doi: 10.1080/07420520601059615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang YE, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954-112963. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moreno-Casbas MT, Alonso-Poncelas E, Gómez-García T, Martínez-Madrid MJ, Escobar-Aguilar G. Perception of the quality of care, work environment and sleep characteristics of nurses working in the National Health System. Enferm Clin. 2018;28(4):230-239. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leung A, Chan C, He J. Structural stability and reliability of the Swedish occupational fatigue inventory among Chinese VDT workers. Appl Ergon. 2004;35:233-241. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peretti S, Tempesta D, Socci V, et al. The role of sleep in aestheticperception and empathy: a mediationanalysis. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(3):e12664. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferri P, Guadi M, Marcheselli L, Balduzzi S, Magnani D, Di Lorenzo R. The impact of shift work on the psychological and physical health of nurses in a general hospital: a comparison between rotating night shifts and day shifts. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;14;9:203-211. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S115326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jensen HI, Larsen JW, Thomsen TD. The impact of shift work on intensive care nurses’ lives outside work: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(3-4):703-709. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asaoka S, Aritake S, Komada Y, et al. Factors associated with shift work disorder in nurses working with rapid-rotation schedules in Japan: the nurses’ sleep health project. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(4):628-636. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.762010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsai K, Lee TY, Chung MH. Insomnia in female nurses: a nationwide retrospective study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2017; 23(1):127-132. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2016.1248604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang CL, Wu MP, Ho CH, Wang JJ. Risks of treated anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. PLOS One. 2018;13(9):e0204224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eletti PL, Peresson L. Clinical experience in communication in autogenous psychotherapy and hypnosis. Minerva Med. 1983; 74(51-52):2957-2964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Manzoni G, Pagnini F, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1471244X-8-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kumar R, Slavish D, Messman B, et al. Associations between pain, depression, stress, and substance use in nurses with and without insomnia. Sleep. 2019;42(1):A168. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz067.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kang W, Jang KH, Lim HM, Ahn JS, Park WJ. The menstrual cycle associated with insomnia in newly employed nurses performing shift work: a 12-month follow-up study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019;92(2):227-235. doi: 10.1007/s00420-018-1371-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Futenma K, Asaoka S, Takaesu Y, et al. Impact of hypnotics use on daytime function and factors associated with usage by female shift work nurses. Sleep Med. 2015;16(5):604-611. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sun Q, Ji X, Zhou W, Liu J. Sleep problems in shift nurses: a brief review and recommendations at both individual and institutional levels. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(1):10-18. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dalky HF, Raeda AF, Esraa AA. Nurse managers’ perception of night-shift napping: a cross-sectional survey. Nurs Forum. 2018;53(2):173-178. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haluza D, Schmidt VM, Blasche G. Time course of recovery after two successive night shifts: a diary study among Austrian nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(1):190-196. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Camerino D, Sandri M, Sartori S, Conway PM, Campanini P, Costa G. Shiftwork, work-family conflict among Italian nurses, and prevention efficacy. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27(5):1105-1123. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.490072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kunst JR, Løset GK, Hosøy D, et al. The relationship between shift work schedules and spillover in a sample of nurses. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2014;20(1):139-147. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2014.11077030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Axelsson J, Åkerstedt T, Kecklund G, Lowden A. Tolerance to shift work–how does it relate to sleep and wakefulness? Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2004;77:121-129. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0482-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mallon L, Broman JE, Akerstedt T, Hetta J. Insomnia in Sweden: a population-based survey. Sleep Disord. 2014;2014:843126. doi: 10.1155/2014/843126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Åkerstedt T, Hallvig D, Kecklund G. Normative data on the diurnal pattern of the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale ratings and its relation to age, sex, work, stress, sleep quality and sickness absence/illness in a large sample of daytime workers. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(5):559-566. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]