Abstract

Distal clavicle fractures are common in patients with shoulder injuries. We retrospectively evaluated the clinical outcomes of a novel fixation technique using a miniature locking plate with a single button in patients with distal clavicle fractures associated with coracoclavicular ligament disruption. The study involved seven patients with distal clavicle fractures with a follow-up period of 12 months. All patients were diagnosed with type IIb fractures according to the Neer classification. The distal clavicle fracture was fixed with a miniature locking plate, and the coracoclavicular ligaments were reconstructed using a single button. Functional outcomes were assessed at the final follow-up visit. At the 1-year follow-up, all patients had achieved radiographic union. There were no cases of nonunion or osteolysis. The mean Constant score at the final follow-up was 88 ± 5.13 (range, 78–93); the mean Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score was 19.17 ± 7.70 (range, 11.67–25); and the mean University of California Los Angeles score was 30 ± 2.52 (range, 25–33). In summary, internal fixation using a miniature locking plate and coracoclavicular reconstruction with a single button is a reliable surgical technique for restoring stability in patients with Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures.

Keywords: Distal clavicle fracture, Neer type IIb, locking plate, button, coracoclavicular ligament, functional outcome

Introduction

Because of the subcutaneous position of the clavicle, fractures of the clavicle are common in patients with shoulder injuries. Approximately 16.6% of all clavicle fractures occur in the lateral third distal to the conoid tubercle, and 52.8% of them are displaced. 1 Neer 2 and Craig 3 classified distal clavicle fractures into five types. According to their definition, in type IIb fractures, the proximal fragment is detached from the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments, whereas the lateral fragment remains attached to the scapula via the acromioclavicular (AC) joint capsule.2,3 The distal fragment is pulled by the weight of the arm and the strong pectoral and latissimus dorsi muscles, whereas the proximal fragment is pulled by the trapezius muscle posteriorly, causing instability in type IIb fractures. 4 The nonunion rate after nonsurgical treatment of Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures reportedly ranges from 30% to 45%.3,4 Risk factors for nonunion include advancing age, fracture displacement, and mechanical failure.5,6 Surgical management is recommended for type IIb distal clavicle fractures.

Various methods have been developed for fixation of type IIb distal clavicle fractures. Early fixation techniques were mainly transacromial Kirschner wire (K-wire) fixation and Knowles pin fixation.3,7–10 Alternatively, K-wire fixation with a tension band has been reported.11,12 Fixation with a CC screw has also been suggested. This type of fixation has a remarkable healing rate but causes more immobilization.13,14 CC ligament fixation with a polyethylene terephthalate tape loop and direct suture fixation of the fragments has been reported.15,16 A distal clavicle locking plate or a hook plate can also be used to capture the lateral fragment.17–19 The combination of a locking plate with a titanium cable under the guide has shown promising curative effects. 19 However, all of these fixation methods have drawbacks, including delayed union, nonunion, and implant failure.

In type IIb distal clavicle fractures, the lateral fragment is often too small and comminuted to allow implantation of enough screws for fixation with an anatomic plate, resulting in relatively high failure rates with this technique. The use of an anatomic locking plate in combination with CC ligament reconstruction remarkably improves the reliability of internal fixation, but it may be difficult to place both implants at satisfactory sites. In addition, this method leads to increased cost. In the current study, we developed a modified fixation system for treating patients with Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures with a miniature locking plate and a single button. The present report describes this novel fixation technique and its clinical outcomes.

Methods

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital [SH9H-2019-T28-1] on 16 September 2019. Written informed consent to undergo treatment was obtained from all participants involved in this study, and all patients’ details were de-identified prior to publication. The reporting of this study conforms to the STROBE statement. 20

We conducted a retrospective study of seven consecutive patients who underwent surgery in our department from 2015 to 2017. After review of the patients’ radiographic films, all patients were diagnosed with Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures and were treated with miniature locking plate fixation in combination with a single button.

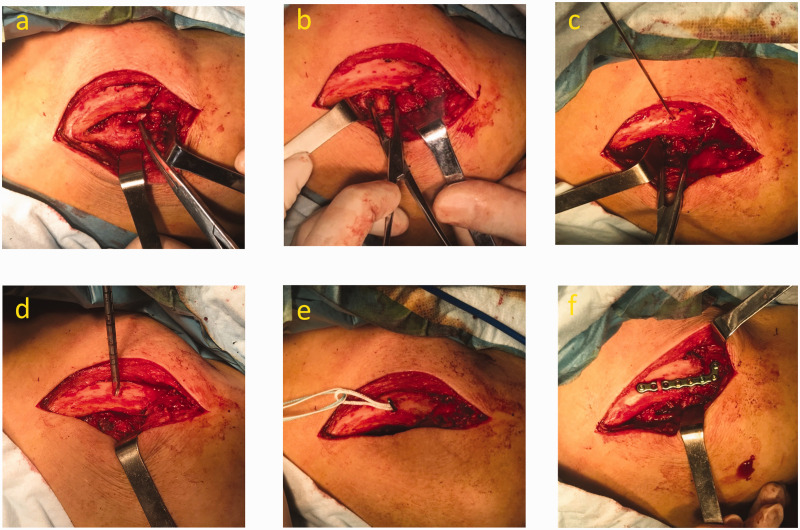

All procedures were performed by the same surgeon (C.Y.). Surgery was performed under general anesthesia with the patient in the beach chair position. An 8-cm curved incision was made at the distal end of the clavicle, and the periosteum was cut layer by layer along the surface of the clavicle to expose the fracture site (Figure 1(a)). The attachment of the deltoid to the anterior surface of the clavicle was dissected to expose the base of the coracoid process. During the procedure, care was taken to maintain the integrity of the AC joint without damaging the AC ligament. The fracture ends were debrided of fibrous tissue, and the CC ligament was explored to confirm rupture of the conoid ligament. The width of the coracoid process was determined by clamping both sides of the coracoid process with an avascular clamp (Figure 1(b)). After reduction of the fracture, a guide pin was inserted into the center of the cross point between the coracoid process and the clavicle (Figure 1(c)).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the surgical technique using a miniature locking plate with a single button. (a) An 8-cm curved incision was made at the distal end of the clavicle, and rupture of the coracoclavicular ligament was confirmed. (b) The width of the coracoid process was determined by clamping both sides of the coracoid process with an avascular clamp. (c) A guide pin was inserted into the center of the cross point between the coracoid process and the clavicle. (d) The drill penetrated four layers of the cortex of the clavicle and the coracoid process along the guide needle. (e) A button was pushed through the drill holes and deployed under the inferior surface of the coracoid. (f) The button loop was tied around the miniature locking plate.

A 4.0-mm drill was used to penetrate four layers of the cortex of the clavicle and the coracoid process along the guide needle (Figure 1(d)). The loop length was determined by measuring the channel length from the superior surface of the clavicle to the inferior surface of the coracoid with a depth gauge. A button (Endobutton; Smith & Nephew Inc., London, UK) of suitable loop length was pushed through the drill holes and deployed under the inferior surface of the coracoids (Figure 1(e)). With the fracture held in reduction, the loop stitch was pulled up until only the tip protruded from the clavicular hole, and a miniature locking plate (F3 Fragment Plating System; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) was then slid into the loop and applied on the superior surface of the distal clavicle (Figure 1(f)). Notably, the plate did not cross the AC joint. The medial fragment was fixed by three locking or nonlocking screws, and the lateral fragment was fixed with three 2.5-mm locking screws. The loop was fixed in the groove between the two screw holes on the plate, and no screw was inserted into the adjacent two holes to avoid cutting the loop. Reduction and the position of internal fixation were again assessed with intraoperative fluoroscopy. Routine irrigation of the wound was performed, and the incision was closed layer by layer.

Postoperative management was identical for all patients. The shoulder was protected with an arm sling for 1 to 2 weeks. Pendulum exercises of the shoulder in the arm sling were allowed as soon as pain permitted. Active shoulder exercises were allowed 3 to 4 weeks after surgery depending on the patient’s clinical situation.

All patients were followed up at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively. At each outpatient visit, the patients were assessed clinically with a physical examination and radiographically with an anteroposterior plain film of the shoulder joint. Successful union was defined by obliteration of the fracture gap on the plain film and no tenderness or pain at the fracture site during shoulder exercises. For assessment of shoulder functional outcomes, the Constant score, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score, and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score were recorded at the last follow-up by a surgeon (H.Y.) who was not involved in the patients’ treatment.21–23

Results

We retrospectively reviewed seven patients (five men, two women) with a mean age of 48.57 ± 16.18 years (range, 28–76 years). The mechanism of injury was traumatic in all cases and included falling from a standing height in three patients, traffic accident in three patients, and sports injury in one patient. The left shoulder was fractured in three patients and the right shoulder was fractured in four. On initial assessment, no patient had neurologic compromise. The interval to the operation, operative time, and intraoperative blood loss (blood volume from the suction apparatus) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient information and clinical outcomes.

| Case No. | Sex | Age (years) | Side | Mechanism of injury | Interval to operation (days) | Operative time (minutes) | Blood loss (mL) | Constant score | DASH score | UCLA score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 44 | Left | Fall | 5 | 58 | 62 | 88 | 15 | 31 |

| 2 | M | 39 | Left | Sport | 11 | 83 | 80 | 93 | 11.67 | 33 |

| 3 | M | 60 | Left | Bicycle accident | 3 | 70 | 58 | 85 | 25 | 29 |

| 4 | M | 38 | Right | Motorcycle accident | 4 | 67 | 50 | 90 | 17.5 | 31 |

| 5 | F | 28 | Right | Bicycle accident | 3 | 55 | 75 | 92 | 12.5 | 31 |

| 6 | M | 76 | Right | Fall | 8 | 74 | 68 | 78 | 33.33 | 25 |

| 7 | M | 55 | Right | Fall | 17 | 62 | 50 | 90 | 19.17 | 30 |

DASH, Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand; UCLA, University of California Los Angeles; F, female; M, male.

One-year follow-up data were obtained for all seven patients. Overall, patient satisfaction was high in all cases. Individual functional outcome scores are shown in Table 1. The mean Constant score at the final follow-up was 88 ± 5.13 (range, 78–93), the mean DASH score was 19.17 ± 7.70 (range, 11.67–25), and the mean UCLA score was 30 ± 2.52 (range, 25–33). At the 1-year follow-up, all patients had achieved radiographic union. There were no cases of nonunion or osteolysis. There were also no hardware-associated complications, including breakage or fracture. No surgical site infections or perioperative fractures were observed. No patients developed hardware irritation or prominence.

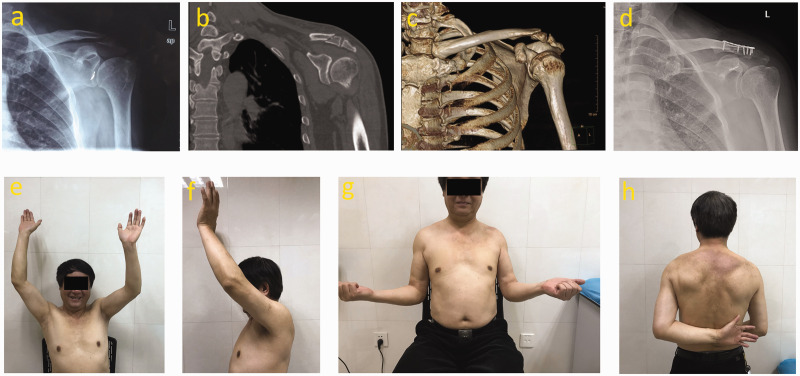

A representative case is described as follows. A 61-year-old man fell on his left shoulder 2 days before hospitalization. He had a history of scapulohumeral periarthritis. A plain film and computed tomography scan showed a Neer type IIb distal clavicle fracture (Figure 2(a)–(c)). The distal clavicle fracture was fixed with a miniature locking plate, and the CC ligaments were reconstructed using a single button (Figure 2(d)). Twelve months after the injury, the patient had a pain-free, stable shoulder with flexion of 0 to 135 degrees and abduction of 0 to 120 degrees (Figure 2(e), (f)). External and internal rotation on the injured side were slightly limited compared with the contralateral arm (Figure 2(g), (h)), which might have been due to the history of scapulohumeral periarthritis.

Figure 2.

Preoperative and postoperative X-rays of Neer type IIb distal clavicle fracture and photographs demonstrating range of motion. (a) Preoperative anteroposterior shoulder X-ray. (b and c) Computed tomography reconstruction of the injured shoulder. (d) Postoperative anteroposterior shoulder X-ray. (e–h) Twelve-month postoperative photographs demonstrating healing and return to preinjury level of function.

Discussion

Surgical treatment of Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures involves internal fixation of the distal clavicle, CC ligament reconstruction, or a combination of both. Although all of these methods have been reported to achieve positive clinical results, none has been shown to be superior to the others.

Commonly used operative techniques for internal fixation of distal clavicle fractures include transacromial K-wire or Knowles pin fixation, use of a distal clavicle anatomic locking plate, and use of a hook plate. 24 To date, many orthopedic surgeons have recommended anatomic locking plates to treat type IIb fractures, and satisfactory clinical results and high union rates have been obtained. However, some argue that in Neer type IIb fractures, the lateral fragment is often too small and comminuted to accommodate enough screws, and the fixation may not provide sufficient mechanical strength. Biomechanical studies performed by Madsen et al. 25 showed that the distal fragment of type IIb distal clavicle fractures needed at least five-screw fixation to effectively withstand the moderate force required for postoperative rehabilitation training (40 to 80 N). Therefore, the authors implied that the plate-and-screw construct alone was not sufficient when it was not possible to obtain fixation with five screws in the small or comminuted distal fragment.25,26 An alternative option is a hook plate mounted on the medial fragment of the fracture that serves as a lever below the acromion. Screws can be implanted on the distal end of the plate to enhance fixation. Unfortunately, however, this frequently used method is associated with a higher complication rate than other methods. Complications include AC joint arthritis, shoulder dysfunction, acromion impingement, rotator cuff injury, and stress fracture.27–29 Therefore, consensus has been reached on the need to remove the implant approximately 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively. 30

Some Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures are treated with CC ligament reconstruction without supplemental fixation. Commonly used techniques include the use of cerclage wires, coracoid loops, suture anchors, double Endobutton plates, and tendon grafts. 28 Motamedi et al. 31 suggested that there was no significant difference in the mean failure load and mean stiffness between the intact CC ligament complex and commonly used augmentations, such as braided polydioxanone and polyethylene. However, Shin et al. 32 reported one case of nonunion and two cases of delayed union in a series of 19 patients who had distal clavicle fractures associated with CC ligament disruption treated surgically with two suture anchors combined with two nonabsorbable suture tension bands.

The use of CC ligament reconstruction alone cannot provide the rigid fixation that is required for fracture healing and early joint mobilization. The potential risks of fixing type IIb distal clavicle fractures merely with CC ligament reconstruction include insufficient fixation strength, loss of fracture reduction, and fracture displacement. Especially when the lateral fragments are highly displaced and the surrounding soft tissues, such as the fascia of the deltoid and trapezius muscle, are compromised, CC ligament reconstruction alone is likely to lead to nonunion or delayed union.

From a biomechanical perspective, the importance of the CC ligaments in controlling superior and horizontal translation of the AC joint has been elucidated. 33 Given the unstable characteristics of Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures, the mainstream therapy has shifted to the use of locking plates with additional CC fixation. 24 In Neer type IIb fractures, CC ligament injuries result in significant displacement of the fracture fragments. Previous biomechanical studies have shown that reconstruction of the CC ligament can reduce the forces on the internal fixation and that the use of a locking plate with CC fixation can provide better fracture stability than the use of either alone.25,33,34 The combination of an anatomic plate with CC fixation may lead to increased fracture healing rates and reduced failure rates.19,35

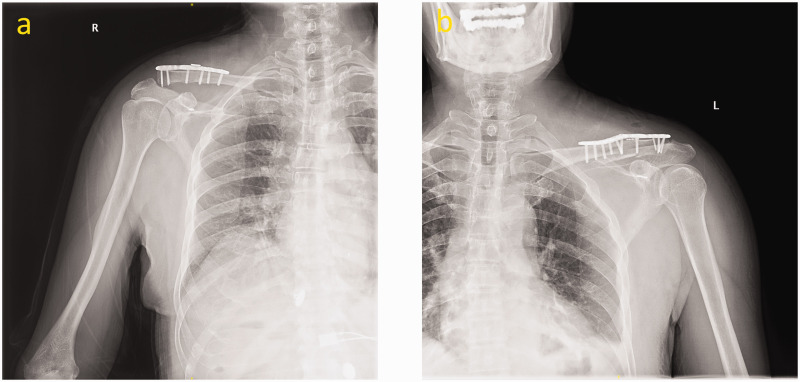

In our institution, we previously treated Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures with an anatomic locking plate and double buttons. Although this approach provided satisfactory clinical results, there were drawbacks. Because the locking plate was wide and occupied most of the space, the button was usually placed above or beneath the locking plate (Figure 3), which might have a galvanic effect. Alternatively, the button could be placed anterior or posterior to the locking plate; however, iatrogenic clavicle fractures would be likely to occur. Moreover, if the position of the button deviates from the middle line of the clavicle, cutting of the loop is likely.

Figure 3.

Postoperative X-rays demonstrating the placement of double buttons and an anatomic locking plate. The button was placed (a) above or (b) beneath the anatomic locking plate.

In this study, we used a miniature locking plate and a single Endobutton as a system to treat Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures. This approach provides the following benefits over existing approaches. (1) A modified fixation system that includes a miniature locking plate and a single button can simultaneously fix the fracture and reconstruct the CC ligament. (2) The miniature locking plate provides 2.5-mm locking screw holes on the distal end; these are smaller in diameter than the 2.7-mm holes on most anatomic locking plates. The smaller diameter allows more screw implantation to increase purchase in the bone and obtain adequate fixation. (3) Because the miniature plate is thin and narrow, the loop stitch can be tied around the miniature locking plate, which avoids the conflict of plate setup and reduces the expense of the implant. (4) The button provides more rigid fixation than a suture anchor, reducing the risk of loosening. We treated seven patients with this system, and no loosening or implant failure was observed during follow-up.

Our study was not without limitations. Because the study was retrospective with prospective follow-up, it was affected by selection bias. Although the results are promising, the sample size was small and there was no control group. Final follow-up was obtained in all cases, but long-term follow-up outcomes remain to be seen.

Conclusions

The herein-described novel internal fixation system to treat Neer type IIb distal clavicle fractures includes a miniature locking plate and a single button. This system may stabilize the fracture site and reconstruct the CC ligament with reasonable efficacy in clinical practice.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81601918), Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 19ZR1429100), and Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital “Cross Research Fund of Medical Engineering” (Grant No. JYJC201915).

ORCID iD: Chao Yu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4969-4480

Author contributions

Chao Yu performed the operation. Hua Ying and Jihuan Wang participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. Fei Yang was the major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. Yuehua Sun and Kerong Dai read and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All the data will be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author of the present paper.

References

- 1.Postacchini F, Gumina S, De Santis P, et al. Epidemiology of clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11: 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neer CS., 2nd. Fracture of the distal clavicle with detachment of the coracoclavicular ligaments in adults. J Trauma 1963; 3: 99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig E. Fractures of the clavicle. In: Rockwood CA. Jr and Matson FA. III (eds) The shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neer CS., 2nd . Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1968; 58: 43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, et al. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86: 1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rollo G, Pichierri P, Marsilio A, et al. The challenge of nonunion after osteosynthesis of the clavicle: is it a biomechanical or infection problem? Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2017; 14: 372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fann CY, Chiu FY, Chuang TY, et al. Transacromial Knowles pin in the treatment of Neer type 2 distal clavicle fractures: a prospective evaluation of 32 cases. J Trauma 2004; 56: 1102–1105; discussion 1105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang SJ, Wong CS. Extra-articular Knowles pin fixation for unstable distal clavicle fractures. J Trauma 2008; 64: 1522–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskola A, Vainionpää S, Pätiälä H, et al. Outcome of operative treatment in fresh lateral clavicular fracture. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1987; 76: 167–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons FA, Rockwood C., Jr . Migration of pins used in operations on the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72: 1262–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mall JW, Jacobi CA, Philipp AW, et al. Surgical treatment of fractures of the distal clavicle with polydioxanone suture tension band wiring: an alternative osteosynthesis. J Orthop Sci 2002; 7: 535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badhe S, Lawrence T, Clark D. Tension band suturing for the treatment of displaced type 2 lateral end clavicle fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007; 127: 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballmer F, Gerber C. Coracoclavicular screw fixation for unstable fractures of the distal clavicle. A report of five cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazal M, Saksena J, Haddad F. Temporary coracoclavicular screw fixation for displaced distal clavicle fractures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2007; 15: 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg JA, Bruce WJ, Sonnabend DH, et al. Type 2 fractures of the distal clavicle: a new surgical technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997; 6: 380–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webber MC, Haines JF. The treatment of lateral clavicle fractures. Injury 2000; 31: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celestre P, Roberston C, Mahar A, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of clavicle fracture plating techniques: does a locking plate provide improved stability? J Orthop Trauma 2008; 22: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalamaras M, Cutbush K, Robinson M. A method for internal fixation of unstable distal clavicle fractures: early observations using a new technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Guan J, Liu M, et al. Treatment of distal clavicle fracture of Neer type II with locking plate in combination with titanium cable under the guide. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coghlan JA, Bell SN, Forbes A, et al. Comparison of self-administered University of California, Los Angeles, shoulder score with traditional University of California, Los Angeles, shoulder score completed by clinicians in assessing the outcome of rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdahl C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: longitudinal construct validity and measuring self-rated health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constant CR, Gerber C, Emery RJ, et al. A review of the Constant score: modifications and guidelines for its use. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee R, Waterman B, Padalecki J, et al. Management of distal clavicle fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011; 19: 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madsen W, Yaseen Z, LaFrance R, et al. Addition of a suture anchor for coracoclavicular fixation to a superior locking plate improves stability of type IIB distal clavicle fractures. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han L, Hu Y, Quan R, et al. Treatment of Neer IIb distal clavicle fractures using anatomical locked plate fixation with coracoclavicular ligament augmentation. J Hand Surg Am 2017; 42: 1036.e1-e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadarajah R, Mahaluxmivala J, Amin A, et al. Clavicular hook–plate: complications of retaining the implant. Injury 2005; 36: 681–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flinkkilä T, Ristiniemi J, Lakovaara M, et al. Hook-plate fixation of unstable lateral clavicle fractures: a report on 63 patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77: 644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stegeman SA, Nacak H, Huvenaars KH, et al. Surgical treatment of Neer type-II fractures of the distal clavicle: a meta-analysis. Acta Orthop 2013; 84: 184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henkel T, Oetiker R, Hackenbruch W. Treatment of fresh Tossy III acromioclavicular joint dislocation by ligament suture and temporary fixation with the clavicular hooked plate. Swiss Surg 1997; 3: 160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motamedi AR, Blevins FT, Willis MC, et al. Biomechanics of the coracoclavicular ligament complex and augmentations used in its repair and reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2000; 28: 380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin SJ, Roh KJ, Kim JO, et al. Treatment of unstable distal clavicle fractures using two suture anchors and suture tension bands. Injury 2009; 40: 1308–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda K, Craig E, An K, et al. Biomechanical study of the ligamentous system of the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986; 68: 434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rieser GR, Edwards K, Gould GC, et al. Distal-third clavicle fracture fixation: a biomechanical evaluation of fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22: 848–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schliemann B, Roßlenbroich SB, Schneider KN, et al. Surgical treatment of vertically unstable lateral clavicle fractures (Neer 2b) with locked plate fixation and coracoclavicular ligament reconstruction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133: 935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data will be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author of the present paper.