Abstract

Objectives

During the pandemic, anxiety and depression may occur increasingly in the whole society. The aim of this study was to evaluate the possible cause, incidence and levels of anxiety and depression in the relatives of the patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) in accordance with the patients’ SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result.

Materials and Method

The study was prospectively conducted on relatives of patients admitted to tertiary intensive care units during COVID‐19 pandemic. Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients and their relatives were recorded. “The Turkish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale” was applied twice to the relatives of 120 patients to determine the symptoms of anxiety and depression in accordance with the PCR results of the patients (PCR positive n = 60, PCR negative n = 60).

Results

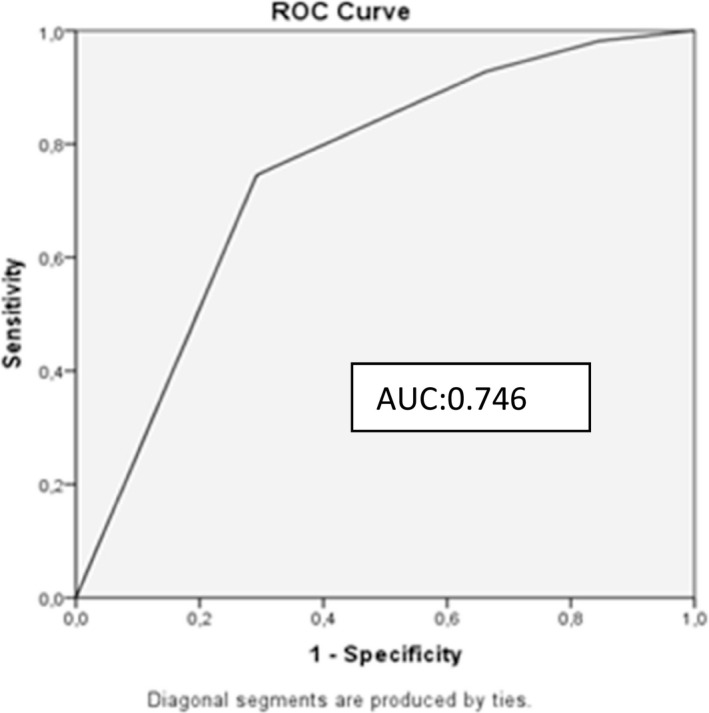

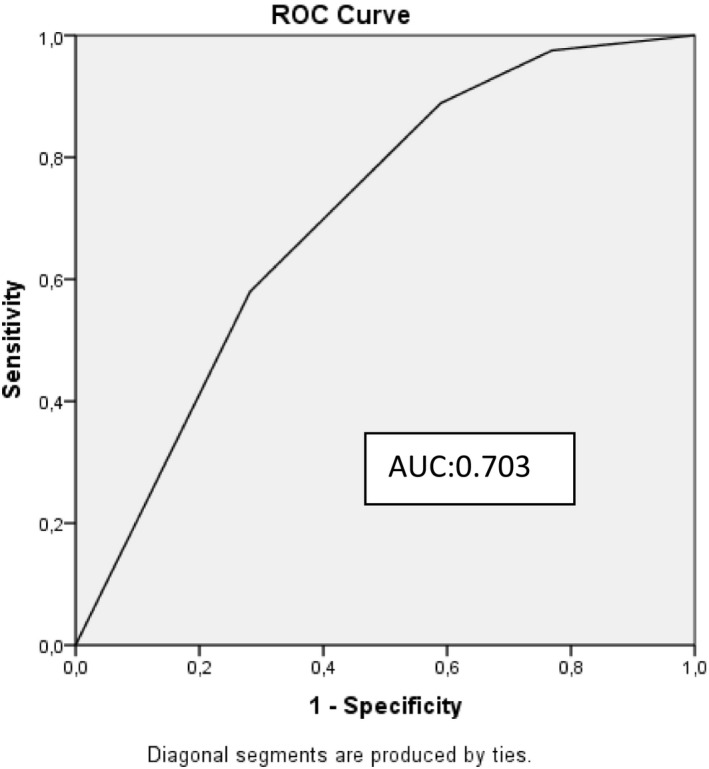

The ratios above cut‐off values for anxiety and depression among relatives of the patients were 45.8% and 67.5% for the first questionnaire and 46.7% and 62.5% for the second questionnaire, respectively. The anxiety and depression in the relatives of PCR‐positive patients was more frequent than the PCR negative (P < .001 for HADS‐A and P = .034 for HADS‐D). The prevalence of anxiety and depression was significantly higher in female relatives (P = .046 for HADS‐A and P = .009 for HADS‐A). There was no significant correlation between HADS and age of the patient or education of the participants. The fact that the patients were hospitalised in the ICU during the pandemic was an independent risk factor for anxiety (AUC = 0.746) while restricted visitation in the ICU was an independent risk factor for depression (AUC = 0.703).

Conclusion

Positive PCR and female gender were associated with both anxiety and depression while hospitalisation in the ICU due to COVID‐19 was an independent risk factor for anxiety and restricted visitation in the ICU is an independent risk factor for depression.

What’s known?

Anxiety and depression became more frequent following COVID‐19 outbreak.

The high transmission rate of COVID‐19 is a concern all over the world.

There are various reasons for concern.

What’s new?

We revealed some of the causes of anxiety and depression in the relatives of patients treated ICU due to the COVID‐19 in pandemic.

Hospitalisation of a relative in the intensive care unit due to COVID‐19 is an independent risk factor for anxiety and the restricted visitation in the ICU is an independent risk factor for depression.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), which was first isolated in Wuhan, China in December 2019, spread all over the world and caused a pandemic in a short time. The pandemic and its consequences still cause serious problems affecting people all over the world.

The answers to many questions such as how long the pandemic will last or when it will end, whether the vaccine will be effective are not yet clear. These uncertainties added to restrictions due to the epidemic also negate the socioeconomic status. In addition to all these, when COVID‐19 is suspected in their loved ones, even otherwise healthy people may show symptoms of sleeping problems, stress, anxiety, and depression along with behaviours such as fear, anger and denial. 1

In Turkey, after the first case detected on 11 March 2020, despite intermittent quarantine practices and social isolation, COVID‐19 cases persist and even rise. 2 While some of these patients were treated at home, some were treated in hospital wards and intensive care units (ICU). Due to the high risk of human‐to‐human transmission of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus, infected individuals must isolate themselves from the society as well as the family members throughout their illness. In our country, The Ministry of Health restricted patient visits, especially in the pandemic ICUs starting from the beginning of the pandemic for the same reason. Relatives of these patients cannot see, touch, or talk to them under these circumstances. Another difference from the pre‐pandemic period is that doctors report their patients’ progress through phone calls, not face‐to‐face.

Anxiety and depression are not rare among relatives of the patients in the ICU. 3 During the pandemic, visit and interview restrictions are expected to increase these symptoms. Even without a pandemic, we can say that being a relative of an intensive care patient is a stress factor itself while it is much worse in a pandemic which has many uncertainties.

Various studies have been conducted to measure the degree of anxiety and depression caused by the pandemic and quarantine period in various patient groups or healthy individuals since the beginning of the pandemic. 4 , 5 Post‐traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression levels in general population are shown to be higher in China, where the pandemic started and then Italy, which is one of the most affected European countries, respectively. 6 , 7 We did not encounter any study in the literature concerning anxiety and depression levels in the relatives of the patient being treated in the ICU due to COVID‐19.

The aim of this study was to compare the incidence and levels of anxiety and depression in the relatives of the patients who were admitted to pandemic intensive care units, diagnosed with [polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result positive] or without COVID‐19 (PCR result negative), and also to evaluate the factors that may cause anxiety and depression.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Patient data

This study was prospectively conducted on the relatives of the patients who were admitted to the tertiary pandemic intensive care units of Ankara City Hospital between 15 May 15 and 15 July 2020 after the approval of the ethics committee (Ethics committee number: E1‐20‐526).

Turkish‐speaking relatives aged eighteen and over of 120 patients who were admitted to the ICU with suspected COVID‐19 due to clinical or radiological findings and subsequently received a positive PCR result (n = 60) or not (n = 60) were included.

The consents of the participants were obtained verbally during the phone call, due to the pandemic and the Ministry of Health’s restriction visitation for the patient’s relatives. The “Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)” was applied to the relatives of the ICU patients twice on the phone by the intensivist who followed the patient and gave information. Before HADS, 7 different questions with 4‐point scale ranging from 0 to 3 were asked to the participants to determine the causes of anxiety and depression (Table 1). HADS was first applied while the diagnosis of COVID‐19 was not yet clear, and then repeated after the PCR test results were confirmed as positive or negative. Participants with previous or ongoing psychiatric illnesses as well as the ones who refused to participate in the study or could not communicate or cooperate enough to complete the questionnaire during phone call were excluded from the study. Patients with nonconfirmed PCR results were also excluded.

TABLE 1.

Questions evaluating the cause of anxiety and depression

| Question 1. How concerning is your patient’s hospitalisation in the ICU due to an epidemic? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 2. How much are you concerned about getting sick from your patient? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 3. How concerning is it not being able to visit your patient in the ICU? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 4. How concerning is the way you receive information about your patient (over the phone)? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 5. How concerning is the frequency of getting information about your patient (3 times a week)? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 6. How concerning is isolation due to the pandemic? | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

| Question 7. Is there any other reason that concerns you apart from the above reasons? If yes, please indicate how concerning it is | |||

| 0) Not at all | 1) Sometimes | 2) Very often | 3) Most of the time |

Gender, age, education (primary school, high school, university, illiterate), marital status (married, single, divorced, widow) of the patients and the participants were recorded. The patients were divided into two groups according to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE‐II) score in the ICU as low mortality risk (≤20) and high mortality risk (≥21) groups. Expected mortality risks and PCR results were declared on the phone, before the second questionnaire. According to World Health Organization age classification, patients were divided into three groups as 18‐65, 66‐80, 81‐99 years. 8 The degree of kinship was evaluated in four groups including spouse, child, relative or sibling. The occupations of the participants were classified as private employee, civil servant, unemployed or student.

HADS, was found by Zigmond and Snaith and translated and validated for the Turkish society by Aydemir et al to evaluate the degree of anxiety and depression of the participants. 9 , 10 HADS consists of 14 questions with a 4‐point scale ranging between 0 and 3 points. The general HADS score is the total score of all the 14 questions asked (0‐42 points) while anxiety score (HADS‐A) is calculated by adding up the 7 odd‐numbered questions (0‐21 points) and the depression score (HADS‐D) by adding up the 7 even‐numbered questions (0‐21 points). HADS was applied to the participants on the phone and the score was calculated using the answers recorded. According to the validation of the HADS for the Turkish society, the values >10 and >7 were considered as cut‐off values for anxiety and depression respectively. 10 Participants were evaluated in 3 subgroups for anxiety and depression as normal (0‐10 for HADS‐A and 0‐7 for HADS‐D), moderate (11‐15 for HADS‐A and 8‐10 for HADS‐D) and high (16‐21 for HADS‐A and 11‐21 for HADS‐D).

2.2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data obtained in the study was evaluated using the “SPSS for windows 23.0” statistical software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. After evaluating the conformity of numerical data to normal distribution by Shapiro‐Wilkonsin test, student’s t test was used to compare numerical data with normal distribution and the result was evaluated according to the equality of variances and Mann‐Whitney U test was used to compare numerical data without normal distribution. Categorical data was given as numbers. Pearson Chi‐Square test and Fisher Exact test were used to compare categorical data. Paired t or Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test was used after evaluating the compatibility of the difference to normal distribution in the comparison of the first and second results of the questionnaires. Logistic regression analysis was performed separately for each question in Table 1 to determine the factors associated with the presence of depression and anxiety. Receiver operating caracteristic (ROC) curves were drawn for effective factors and the area under the curve (AUC) values were calculated. P < .05 was considered significant.

Sample size was not determined previously. Post hoc power analysis of the study was calculated at the end of the study with G‐Power, the power of the study was 86% for the comparison made according to the PCR result, 85% for the comparison made according to the participant’s gender, 81% for the comparison made according to the APACHE‐II score and the questions 1 and 3 obtained through logistic regression 88% and 82% respectively.

3. RESULTS

The results of 120 out of 160 patients’ relatives were included in the statistical evaluation. Twenty‐two of the participants were excluded because their patients were transferred to the ward from the ICU before the completion of the second test, 10 were excluded because their patients died before the second test was performed, 7 were excluded because of unavailability through phone, and 1 participant was excluded because the patient was coming from a nursing home and the questionnaire was answered by a staff, not a relative.

When all patients were evaluated, the average age was 70.22. Sixty (50%) patients were male with an average age of 66.48 and sixty (50%) were female with an average age of 73.95. Ninety‐two (76.7%) of the patients were married and 72 (60%) of them were graduated from the primary school (Table 2). The average APACHE‐II score was 17 ± 7 (minimum 3‐maximum 36) and 34 (28.3%) patients required mechanical ventilator.

TABLE 2.

Demographic characteristics of patients and patients’ relatives

| Variables | Patients | Patients’ relatives |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 70.22 ± 14.7 | 43.88 ± 10.9 |

| Female | 73.95 ± 11.9 | 45.8 ± 11.1 |

| Male | 66.48 ± 16.3 | 41.97 ± 10.5 |

| Gender n (%) | ||

| Female | 60 (50) | 48 (40) |

| Male | 60 (50) | 72 (60) |

| Marital status n (%) | ||

| Married | 92 (76.7) | 94 (78.3) |

| Single | 4 (3.3) | 21 (17.5) |

| Divorced | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.5) |

| Widow | 23 (19.2) | 4 (1.7) |

| Education n (%) | ||

| Primary school | 72 (60) | 33 (27.5) |

| High school | 16 (13.3) | 32 (26.7) |

| University | 11 (9.2) | 54 (45) |

| Illiterate | 21 (17.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Degree of kinship n (%) | ||

| Spouse | – | 12 (10) |

| Child | 83 (69.2) | |

| Relative | 20 (16.6) | |

| Sibling | 5 (4.2) | |

| Profession n (%) | ||

| Private employee | – | 53 (44.2) |

| Civil servant | 18 (15) | |

| Retired | 14 (11.6) | |

| Unemployed | 20 (16.7) | |

| Student | 15 (12.5) |

Abbreviations: min‐max, minimum maximum value; SD, standard deviation.

When all participants were evaluated, the average age was 43.88. 72 (60%) were male, 94 (78.3%) were married, 54 (45%) were graduated from the university, 83 (69.2%) were children of the patients, 53 (44.2%) were private employee (Table 2).

There was no difference between the averages of the first and second HADS, HADS‐A and HADS‐D results of the participants (P = .572, P = .974, P = .190 respectively). Participants with HADS‐A and HADS‐D anxiety and depression scale above the cut‐off values were 45.8% and 67.5% for the first test and 46.7% and 62.5% for the second test respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the first and second HADS survey results of participants (patients’ relatives) and comparison of HADS results of participants according to PCR results

| First survey | Second survey | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 120 | n = 120 | ||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 20.35 ± 9.6 | 19.7 ± 10.9 | .572 |

| HADS‐A score (mean ± SD) | 10.28 ± 5.5 | 10.41 ± 5.9 | .974 |

| 0‐10 n (%) | 65 (54.2) | 64 (53.3) | .678 |

| 11‐15 n (%) | 33 (27.5) | 29 (24.2) | |

| 16‐21 n (%) | 22 (18.3) | 27 (22.5) | |

| HADS‐D score (mean ± SD) | 10.07 ± 4.7 | 9.51 ± 5.4 | .190 |

| 0‐7 n (%) | 39 (32.5) | 45 (37.5) | .228 |

| 8‐10 n (%) | 32 (26.7) | 21 (17.5) | |

| 11‐21 n (%) | 49 (40.8) | 54 (45) |

| PCR test | Positive | Negative | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| n =60 | n =60 | ||

| HADS (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 21.23 ± 10.2 | 19.47 ± 8.9 | .315 |

| HADS‐A (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 11.05 ± 5.7 | 9.52 ± 5.2 | .126 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 29 (48.3) | 36 (60) | .298 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 17 (28.3) | 16 (26.7) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 14 (23.3) | 8 (13.3) | |

| HADS‐D (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.18 ± 5.1 | 9.95 ± 4.3 | .786 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 18 (30) | 21 (35) | .813 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 16 (26.7) | 16 (26.7) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 26 (43.3) | 23 (38.3) | |

| HADS (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 23.07 ± 11.4 | 16.77 ± 9.4 | .001 |

| HADS‐A (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 12.33 ± 6.2 | 8.48 ± 5.1 | <.001 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 20 (33.3) | 44 (73.3) | <.001 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 20 (33.3) | 9 (15) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 20 (33.3) | 7 (11.7) | |

| HADS‐D (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.73 ± 5.7 | 8.28 ± 4.7 | .012 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 17 (28.3) | 28 (46.7) | .034 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 9 (15) | 12 (20) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 34 (56.7) | 20 (33.3) |

Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS‐A, hospital anxiety depression scale‐Anxiety score; HADS‐D, hospital anxiety and depression scale‐Depression score; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation, P values written in bold show statistically significance.

There was no statistical difference in the first HADS average of the participants in accordance with the PCR results of the patients but although statistically insignificant, number of participants with anxiety and depression scores above the cut‐off values were higher (HADS‐A; 51.6% for PCR positive, n = 31 and 40% for PCR negative, n = 24 and HADS‐D; 70 % for PCR positive, n = 41 and 65% for PCR negative, n = 39).

When the second HADS results were evaluated, HADS, HADS‐A and HADS‐D averages were significantly higher (P = .001, P < .001, P = .012 respectively), also the ratio of participants with PCR positive patients who had higher scores then the cut‐off values for anxiety and depression were significantly higher than the PCR negative patients (P < .001 for HADS‐A and P = .034 for HADS‐D) (Table 3).

When compared according to gender, the first HADS and HADS‐A scores as well as the first and second HADS‐D scores were significantly higher in female participants (P = .014, .046, .009, .049 respectively) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of HADS results of the participants according to gender and APACHE‐II scores

| Variables | Gender | P | APACHE‐II score | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ≤20 | ≥21 | |||

| n = 48 | n = 72 | n = 83 | n = 37 | |||

| HADS (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 22.77 ± 9.5 | 18.74 ± 9.4 | .014 | 20.41 ± 9.9 | 20.22 ± 9.1 | .919 |

| HADS‐A (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 11.48 ± 5.3 | 9.49 ± 5.5 | .046 | 10.34 ± 5.8 | 10.16 ± 4.8 | .873 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 18 (37.5) | 47 (65.3) | .006 | 42 (50.6) | 23 (62.2) | .471 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 20 (41.7) | 13 (18.1) | 24 (28.9) | 9 (24.3) | ||

| 16‐21 (n) % | 10 (20.8) | 12 (16.7) | 17 (20.5) | 5 (13.5) | ||

| HADS‐D (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 11.29 ± 4.7 | 9.25 ± 4.5 | .009 | 10.07 ± 4.7 | 10.05 ± 4.7 | .984 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 9 (18.8) | 30 (41.7) | .017 | 27 (32.5) | 12 (32.4) | .307 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 13 (27.1) | 19 (26.4) | 19 (22.9) | 13 (35.1) | ||

| ≥11 (n) % | 26 (54.2) | 23 (31.9) | 37 (44.6) | 12 (32.4) | ||

| HADS (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 21.87 ± 11.6 | 18.61 ± 10.2 | .133 | 18.63 ± 10.9 | 22.81 ± 10.4 | .051 |

| HADS‐A (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 11.19 ± 6.5 | 9.89 ± 5.6 | .308 | 9.78 ± 6.1 | 11.81 ± 5.5 | .087 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 25 (52.1) | 39 (54.2) | .276 | 48 (57.8) | 16 (43.2) | .186 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 9 (18.8) | 20 (27.8) | 20 (24.1) | 9 (24.3) | ||

| 16‐21 (n) % | 14 (29.2) | 13 (18.1) | 15 (18.1) | 12 (32.4) | ||

| HADS‐D (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.69 ± 5.5 | 8.72 ± 5.2 | .049 | 8.84 ± 5.3 | 11 ± 5.2 | .042 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 16 (33.3) | 29 (40.3) | .222 | 36 (43.4) | 9 (24.3) | .124 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 6 (12.5) | 15 (20.8) | 14 (16.9) | 7 (18.9) | ||

| ≥11 (n) % | 26 (54.2) | 28 (38.9) | 33 (39.8) | 21 (56.8) | ||

Abbreviations: APACHE‐II Score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score; HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS‐A, hospital anxiety depression scale‐Anxiety score; HADS‐D, hospital anxiety and depression scale‐Depression score; SD, standard deviation, P values written in bold show statistically significance.

When the first and second HADS results were compared in terms of APACHE‐II score, there was no statistical difference (P = .919), but the second HADS‐D results were significantly higher for patients with an APACHE‐II score ≥21 (P = .042) (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Logistic regression analysis results determining independent risk factors for anxiety

| Variable | B (coefficient) | SE | Confidence interval | Odds ratio | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.486 | 0.991 | 88.789 | .000 | |

| Gender of participant | −1.601 | 0.489 | 0.077‐0.526 | 0.202 | .001 |

| Question 1 | −0.908 | 0.327 | 0.212‐0.766 | 0.403 | .006 |

| Question 2 | −0.164 | 0.209 | 0.563‐1.279 | 0.849 | .432 |

| Question 3 | −0.015 | 0.351 | 0.495‐1.960 | 0.985 | .966 |

| Question 4 | −0.142 | 0.277 | 0.504‐1.493 | 0.867 | .607 |

| Question 5 | −0.473 | 0.307 | 0.341‐1.137 | 0.623 | .123 |

| Question 6 | −0.144 | 0.242 | 0.539‐1.391 | 0.866 | .551 |

R2: 0.316 (Cox‐Snell), R2: 0.422 (Nagelkerke) Model Chi square: 45.495 P = .000.

When HADS results were compared according to kinship, the first HADS and HADS‐A results were significantly higher among spouses of the patients than the other relatives (P = .05 and P = .020 respectively) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of the HADS results of the participants according to degree of kinship

| Variables | Degree of kinship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse | Child | Relative | Sibling | P | |

| n = 12 | n = 83 | n = 20 | n = 5 | ||

| HADS (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 27.17 ± 10.43 | 20.11 ± 9.1 | 18.2 ± 10.7 | 16.6 ± 5.4 | .05 |

| HADS‐A (first survey) score (Mean ± SD) | 13.67 ± 5.3 | 10.22 ± 5.4 | 9.35 ± 5.8 | 7 ± 3.1 | .020 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 3 (25) | 45 (54.2) | 13 (65) | 4 (80) | .336 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 5 (41.7) | 23 (27.7) | 4 (20) | 1 (20) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 4 (33,3) | 15 (18,1) | 3 (15) | 0 | |

| HADS‐D (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 13.5 ± 5.4 | 9.89 ± 4.4 | 8.85 ± 5.2 | 9.6 ± 3.1 | .157 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 1 (8.3) | 28 (33.7) | 9 (45) | 1 (20) | .382 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 4 (33.3) | 20 (34.1) | 6 (30) | 2 (40) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 7 (58.3) | 35 (42.2) | 5 (25) | 2 (40) | |

| HADS (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 23.08 ± 11.6 | 19.37 ± 10.5 | 20 ± 12 | 21 ± 13.3 | .750 |

| HADS‐A (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 12.33 ± 6.9 | 10.17 ± 5.8 | 10.3 ± 6.4 | 10.2 ± 6.8 | .572 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 4 (33.3) | 47 (56.6) | 10 (50) | 3 (60) | .867 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 4 (33.3) | 19 (22.9) | 5 (25) | 1 (20) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 4 (33.3) | 17 (20.5) | 5 (25) | 1 (20) | |

| HADS‐D (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.75 ± 5 | 9.2 ± 5.3 | 9.7 ± 5.9 | 10.8 ± 6.6 | .986 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 3 (25) | 34 (41) | 6 (30) | 2 (40) | .537 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 1 (8.3) | 13 (15.7) | 6 (30) | 1 (20) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 8 (66.7) | 36 (43.4) | 8 (40) | 2 (40) | |

Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS‐A, hospital anxiety depression scale‐Anxiety score; HADS‐D, Hospital anxiety and depression scale‐Depression score; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation, P values written in bold show statistically significance.

The average HADS values of participants did not change according to age of the patients, but the HADS average of the participants increased as the age of the patients decreased and, although not statistically significant, as the age of the patients increased, anxiety and depression scales of the participants decreased (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Comparison of the HADS results of the participants according to age of patients

| Variables | Ages of patients | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18‐65 | 66‐80 | 81‐99 | ||

| n = 27 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||

| HADS (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 21.48 ± 9.7 | 20.87 ± 10.2 | 18.62 ± 8.9 | .358 |

| HADS‐A (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.91 ± 5.4 | 10.36 ± 5.9 | 9.54 ± 5.2 | .476 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 21 (50) | 21 (53.8) | 23 (59) | .793 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 14 (33.3) | 11 (28.2) | 8 (20.5) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 7 (16.7) | 7 (17.9) | 8 (20.5) | |

| HADS‐D (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.57 ± 4.9 | 10.51 ± 5 | 9.08 ± 3.9 | .299 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 12 (28.6) | 10 (25.6) | 17 (43.6) | .377 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 10 (23.8) | 13 (33.3) | 9 (23.1) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 20 (47.6) | 16 (41) | 13 (33.3) | |

| HADS (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 21.17 ± 10.7 | 20.54 ± 11.2 | 17.95 ± 10.7 | .294 |

| HADS‐A (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 11.21 ± 6.2 | 10.67 ± 5.9 | 9.28 ± 5.8 | .291 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 18 (42.9) | 20 (51.3) | 26 (66.7) | .202 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 14 (33.3) | 8 (20.5) | 7 (17.9) | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 10 (23.8) | 11 (28.2) | 6 (15.4) | |

| HADS‐D (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 9.95 ± 5.1 | 9.87 ± 5.7 | 8.67 ± 5.4 | .363 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 13 (31) | 14 (35.9) | 18 (46.2) | .278 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 6 (14.3) | 6 (15.4) | 9 (23.1) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 23 (54.8) | 19 (48.7) | 12 (30.8) | |

Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS‐A, hospital anxiety depression scale‐Anxiety score; HADS‐D, hospital anxiety and depression scale‐Depression score; SD, standard deviation.

No significant relation was found between the education of the participants and the HADS results (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Comparison of the HADS results of the participants according to level of education

| Variables | Level of education of participants | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary school | High school | University | Illiterate | ||

| n = 33 | n = 32 | n = 54 | n = 1 | ||

| HADS (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 21.12 ± 10.1 | 22.47 ± 9.3 | 18.7 ± 9.4 | 16 | .621 |

| HADS‐A (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.52 ± 6.1 | 11.44 ± 5 | 9.54 ± 5.4 | 6 | .471 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 17 (51.5) | 12 (37.5) | 35 (64.8) | 1 (100) | .316 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 10 (30.3) | 12 (37.5) | 11 (20.4) | 0 | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 6 (18.2) | 8 (25) | 8 (14.8) | 0 | |

| HADS‐D (first survey) score (mean ± SD) | 10.61 ± 4.6 | 11.03 ± 5 | 9.17 ± 4.5 | 10 | .898 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 9 (27.3) | 8 (25) | 22 (40.7) | 0 | .309 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 8 (24.2) | 8 (25) | 15 (27.8) | 1 (100) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 16 (48.5) | 16 (50) | 17 (31.5) | 0 | |

| HADS (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 19.12 ± 11.8 | 23.41 ± 11.5 | 18.44 ± 9.7 | 14 | .672 |

| HADS‐A (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 9.69 ± 6.6 | 12.69 ± 6.1 | 9.61 ± 5.3 | 0 | .400 |

| 0‐10 (n) % | 18 (54.5) | 11 (34.4) | 34 (63) | 1 (100) | .179 |

| 11‐15 (n) % | 8 (24.2) | 9 (28.1) | 12 (22.2) | 0 | |

| 16‐21 (n) % | 7 (21.2) | 12 (37.5) | 8 (14.8) | 0 | |

| HADS‐D (second survey) score (mean ± SD) | 9.42 ± 5.6 | 10.72 ± 5.8 | 8.83 ± 4.9 | 0 | .920 |

| 0‐7 (n) % | 13 (39.4) | 10 (31.3) | 22 (40.7) | 0 | .388 |

| 8‐11 (n) % | 4 (12.1) | 6 (18.8) | 10 (18.5) | 1 (100) | |

| ≥11 (n) % | 16 (48.5) | 16 (50) | 22 (40.7) | 0 | |

Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS‐A, hospital anxiety depression scale‐Anxiety score; HADS‐D, hospital anxiety and depression scale‐Depression score; SD, standard deviation.

Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate whether the answers to the questions asked to the participants were independent risk factors for anxiety and depression which showed patients’ hospitalisation in the intensive care unit due to pandemic to be an independent risk factor for anxiety among the participants while restricted visitation in the intensive care unit to be an independent risk factor for depression (Tables 8 and 9). ROC curves were drawn. For anxiety in the participants, AUC = 0.746 for question 1 and for depression, AUC = 0.703 for question 3 (Figures 1 and 2).

TABLE 9.

Logistic regression analysis results determining independent risk factors for depression

| Variable | B (coefficient) | SE | Confidence interval | Odds ratio | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.853 | 0.641 | 6.382 | .004 | |

| Gender of participant | −1.213 | 0.487 | 0.114‐0.772 | 0.297 | .013 |

| Question 1 | −0.101 | 0.289 | 0.513‐1.594 | 0.904 | .727 |

| Question 2 | −0.011 | 0.227 | 0.648‐1.578 | 1.011 | .962 |

| Question 3 | −0.722 | 0.319 | 0.260‐0.907 | 0.486 | .023 |

| Question 4 | −0.091 | 0.287 | 0.624‐1.960 | 1.095 | .752 |

| Question 5 | −0.095 | 0.299 | 0.506‐1.635 | 0.909 | .751 |

| Question 6 | −0.297 | 0.250 | 0.455‐1.213 | 0.743 | .235 |

R2: 0.200 (Cox‐Snell), R2: 0.280 (Nagelkerke) Model Chi square: 26.852 P = .000.

FIGURE 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the model predicting anxiety AUC:0.746

FIGURE 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for model predicting depression

Twenty five of the participants stated 10 different reasons for anxiety and depression. Five of them feared death of their patient, 4 feared infecting their families, 3 feared infecting other people, 3 feared the length of time to recovery, 3 feared loss of their jobs or had financial issues, 2 were upset about not getting convenient information through regular calls, 1 was anxious about the education of his child, 1 was anxious because he started working and could get infected, 1 expressed concern about the general spread of the disease and the increasing number of patients, while another expressed concern about the insufficiency and unreliability of the data announced by the Ministry of Health.

4. DISCUSSION

Although there aren’t any studies in the literature evaluating the anxiety and depression in the relatives of the patients during the pandemic, it has been reported before the pandemic that being a relative of a hospitalised patient in the intensive care unit due to a life‐threatening disease is an important stress factor and may cause anxiety and depression. 11 Anxiety and depression rates of relatives of patients in the ICU were evaluated by studies conducted in different countries before the pandemic some of which are as follows: 69.1% and 35.4% in a multicenter trial in France, 71.8% and 53.8% in a trial reported from Brazil, 60% and 54% in another trial from Brazil, 35% and 66% in a trial from India, 35.9% and 71.8% in a trial from Turkey respectively. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 As a result of these trials preceding the pandemic, the anxiety levels in our country is lower than France and Brazil, similar to India while depression levels are higher than France, Brazil and India. When the rates of anxiety and depression in relatives of the patients before the pandemic was compared with the pandemic (35.9% and 71.8% respectively) by Köse et al it can be roughly be said that anxiety levels raised (45.8%‐46.7%) while depression levels decreased (62.5%‐67.5%) during the pandemic. 15

Some of the studies showing the rates of anxiety and depression on the general population during the pandemic are as follows: 29.83% and 16.76% in Russia, 35% and 22% in Austria, 28.8% and 16.5% in China, and 45.1% and 23.6% in Turkey respectively. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 In our country, the anxiety rates in the general population were lower than Russia and Austria but higher than China while depression rates were higher than the rest. Apart from cultural differences, the differences in health care between countries and the onset of the trials as the beginning or mid‐pandemic period or the level of awareness may be responsible for the results. One of the reasons why the anxiety and depression rates in this study were higher than China may be because in China, the study was carried out by WHO as soon as the pandemic was declared while this study started on 3‐6th months of the pandemic in our country. The official onset of the pandemic was different between countries as well. 18 This later onset of COVID‐19 pandemic in our country may be the cause of higher rates of anxiety and depression because of the awareness of transmission routes and speed as well as the mortality rates. National and social media sharing updated information about the number of patients and deaths in the country and in the world, which inclines day by day may also be responsible for the high anxiety and depression rates. Özdin et al also conducted a study concerning the anxiety and depression among healthy volunteers during the pandemic. 19 Depression rates of this study was higher probably because of the population we chose.

In the literature, there is no similar study conducted with relatives of patients hospitalised in ICU during pandemic. Our trial was started at the beginning of the pandemic and all patients were admitted to ICU with suspicion of COVID‐19. The diagnosis was confirmed with PCR in addition to clinical and radiological findings. The higher rates of anxiety and depression in the relatives of patients with positive PCR test can be explained by the serious concerns about the disease. A positive PCR also eliminates the possibility of not having the disease and can incline anxiety and depression.

In this study, we found that symptoms of anxiety and depression are more common in women during the pandemic, consistent with the studies prior to pandemic showing female susceptibility to anxiety and depression. 20 , 21 Studies from different countries conducted in the general population since the beginning of the pandemic also showed tendency to anxiety and depression in female gender. 6 , 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 During the pandemic, female gender was emphasised with regard to anxiety and depression in our country as well. 19 Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle can cause mood changes, which can cause women's reactions to events to be more exaggerated or negative than men. 25 Considering that women have more posttraumatic stress symptoms such as negative alteration of cognition and mood, re‐experiencing and hyperarousal than men in the COVID‐19 epidemic, they are expected to have more anxiety and depression symptoms due to both the pandemic and the anxiety they feel for the wellbeing of their patients. 23 Another factor affecting depression is the role that societies attribute to genders depending on cultural differences. 26 Although the study is carried out in the capital of our country, the cultural mosaic in the city can reflect almost every region of our country since it is a city that continues to receive immigrants from all over the country. In some societies, the under‐reacting of women to the events is regarded as abnormal, while in some regions, the overreaction of men is abnormal. Due to the place of men in society and the role assigned to them, men can show their emotions less than women. The characteristics of the regions where people come from, where they grow up, family and economic structure may be factors that make the reactions of women and men different from each other. Cultural characteristics and the acceptance that the female gender may be emotionally reactive in life may explain the higher frequency of anxiety and depression among females.

The instant systemic condition of the patient was evaluated with the APACHE II score and the expected mortality rate was declared to the relatives of the patient. In a previous manuscript, no relationship was found between the APACHE II scores and the anxiety and depression levels of relatives of the ICU patients; similar to our results in another study, it was reported that APACHE II scores may be associated with depression in the relatives of ICU patients; and in another study with anxiety. 31 , 32 , 33

The higher incidence of depression among the relatives of the patients in the ICU can be because of the hospitalisation of their loved ones in intensive care with the diagnosis of COVID‐19, knowing the condition is severe and possibly lethal.

Another factor in which anxiety and depression rates were significantly higher in this study was if the participant was the spouse of the patient. Followed by the children, relatives, and siblings of the patients. The result of this study was consistent with previous studies. 15 , 30 , 31 Because the spouses share a house, a life, and values, one’s illness effects the surviving spouse both emotionally and socioeconomically. Therefore, we believe that it is an expected result that the symptoms of anxiety and depression are more common in spouses compared to other relatives of the ICU patients.

People aged 65 and over are more likely to have COVID‐19 disease and especially respiratory failure and the need for intensive care than younger patients. 32 However younger patients may also need treatment in intensive care and death of these patients is more devastating for their relatives. In this study, although the age of the patients did not significantly effect the anxiety and depression levels of their relatives, the rates of high anxiety and depression was higher in the relatives of young patients than those of middle aged and elderly patients. In this aspect, it was consistent with the results of other studies. 13 , 26 In the literature, there is no difference between the anxiety and depression levels of the relatives of ICU patients in terms of the education level of the patients’ relatives. 15 , 32 , 33

Most of the participants in the study were university graduates, and although the lowest anxiety and depression levels were found in this group, and there was no significant relationship between the education level of the participants and their anxiety or depression levels. This suggests that education may be effective in the perception process and acceptance of results, but still cannot fully control emotional responses. This study associates anxiety with COVID‐19 as an independent risk factor in accordance with to the answer given to the question “How concerning is your patient’s hospitalisation in the ICU due to an epidemic?” by the participants. A relative hospitalised in the ICU due to an epidemic was found to be effective in the development of anxiety.

With the restrictions made to prevent transmission during the pandemic period and the prohibition of daily patient visits, patients' relatives could not visit their patients in the intensive care environment. Therefore, we think that the lack of seeing, communicating and physical contact in the ICU increases the curiosity and anxiety of the relatives of the patients. Not being able to visit and see a patient was found to be an independent risk factor for the development of depression in the participants.

There may be many different factors that can cause anxiety and depression on people during the pandemic period. Since we had only 25 participants who answered the question about other causes of anxiety and depression, these answers were not evaluated statistically. From these answers, which we have also stated in the findings section, we think that 10 different reasons may cause anxiety in the relatives of the patient during the pandemic process. We believe that these reasons should be questioned in future studies investigating the causes of anxiety and depression.

In conclusion, during the pandemic period, the frequency of anxiety and depression was higher in the relatives of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 in the intensive care unit and female gender was also a precipitating factor for anxiety and depression. Furthermore, a relative is in the intensive care unit due to COVID‐19 is an independent risk factor for anxiety while restricted visitation in the ICU is an independent risk factor for depression.

Limitations: Single center, the number of participants, application of the questionnaires on the phone are the limitations for this study.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Behiye Deniz Kosovali: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Data collection, Drafting article. Nevzat Mehmet Mutlu: Concept/design, Data collection. Canan Cam Gonen: Data collection. Tulay Tuncer Peker: Data analysis/interpretation, Statistics. Asiye Yavuz: Data collection. Ozlem Balkiz Soyal: Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article. Esra Cakır: Data collection. Belgin Akan: Data collection. Derya Gokcinar: Data collection. Deniz Erdem: Data collection. Isıl Ozkocak Turan: Data collection.

Kosovali BD, Mutlu NM, Gonen CC, et al. Does hospitalisation of a patient in the intensive care unit cause anxiety and does restriction of visiting cause depression for the relatives of these patients during COVID‐19 pandemic? Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14328. 10.1111/ijcp.14328

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Author elects to not share data. Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli‐Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID‐19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:317‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr.

- 3. Kourti M, Christofilou E, Kallergis G. Anxiety and depression symptoms in family members of ICU patients. Av Enferm. 2015;33:47‐54. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ernstsen L, Havnen A. Mental health and sleep disturbances in physically active adults during the COVID‐19 lockdown in Norway: does change in physical activity level matter? Sleep Med. 2021;77:309‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Romito F, Dellino M, Loseto G, et al. Psychological distress in outpatients with lymphoma during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. An N = 18147 web‐based 3 survey. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yaşlılık BN, Kavramı Y. Epidemiyolojik Özellikler. In: Ertürk A, Bahadır A, Koşar F, eds. Yaşlılık ve Solunum Hastalıkları: TÜSAD Eğitim Kitapları Serisi; 2018:13‐31. https://www.solunum.org.tr/TusadData/Book/677/17102018112853‐001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361‐370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aydemir Ö, Güvenir T, Küey L, Kültür S. Hastane anksiyete ve depresyon ölçeğinin ürkçe formunun geçerlilik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 1997;8:280‐287. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision‐making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893‐1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maruiti MR, Galdeano LE, Farah OGD. Anxiety and depressions in relatives of patients admitted in intensive care units. Acta Paul Enferm. 2008;21:636‐642. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Midega TD, Barros de Oliveira HS, Fumis RRL. Satisfaction of family members of critically ill patients admitted to a public hospital intensive care unit and correlated factors. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2019;31:147‐155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borges R, Prasanth YM. Psychological and socio‐economic burden on families of patients admitted in intensive care unit. Int J Biomed Res. 2016;7:733‐737. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Köse I, Zincircioğlu Ç, Öztürk YK, et al. Factors affecting anxiety and depression symptoms in relatives of intensive care unit patients. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;3:611‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karpenko OA, Syunyakov TS, Kulygina MA, Pavlichenko AV, Chetkina AS, Andrushchenko AV. Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on anxiety, depression and distress—online survey results amid the pandemic in Russia. Consortium Psychiatricum. 2020;1:8‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fauziah Rabbani F, Khan HA, Piryani S, Khan AR, Abid F. Psychological and social impact of COVID‐19 in Pakistan: need for gender responsive policies. 10.1101/2020.10.28.20221069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Özdin S, Özdin ŞB. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID‐19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:504‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bastian Matt B, Schwarzkopf D, Reinhart K, König C, Hartog CS. Relatives' perception of stressors and psychological outcomes—results from a survey study. J Crit Care. 2017;39:172‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing COVID‐19 patients: a cross‐sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1388‐1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID‐19 outbreak in China hardest‐hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112‐921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gerhold L. COVID‐19: risk perception and coping strategies. Results from a survey in Germany. 10.31234/osf.io/xmpk4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soni M, Curran VH, Kamboj SK. Identification of a narrow post‐ovulatory window of vulnerability to distressing involuntary memories in healthy women. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;104:32‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kleinman A. Culture and depression. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:951‐953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van den Born‐van Zanten SA, Dongelmans DA, Dettling‐Ihnenfeldt D, Vink R, van der Schaaf M. Caregiver strain and posttraumatic stress symptoms of informal caregivers of intensive care unit survivors. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:173‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bolosi M, Peritogiannis V, Tzimas P, Margaritis A, Milios K, Rizos DV. Depressive and anxiety symptoms in relatives of intensive care unit patients and the perceived need for support. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2018;9:522‐528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amass TH, Villa G, OMahony S, et al. Family care rituals in the intensive care unit to reduce symptoms of post‐traumatic stress disorder in family members—a multicenter, multinational, before‐and‐after intervention trial. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:176‐184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722‐1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McAdam JL, Dracup KA, White DB, Fontaine DK, Puntillo KA. Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk for dying. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1078‐1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen Y, Klein SL, Garibaldi BT, et al. Aging in COVID‐19: vulnerability, immunity and intervention. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;65:101‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delva D, Vanoost S, Bijttebier P, Lauwers P, Wilmer A. Needs and feelings of anxiety of relatives of patients hospitalized in intensive care units. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;35:21‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Acaroğlu R, Kaya H, Şendir M, Tosun K, Turan Y. Levels of anxiety and ways of coping of family members of patients hospitalized in the Neurosurgery Intensive Care Unit. Neurosciences. 2008;13:41‐45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Author elects to not share data. Research data are not shared.