Abstract

A virtual pediatric dermatology student‐run clinic was initiated during the COVID‐19 pandemic, when in‐person educational opportunities were limited. The clinic's aim is to provide high‐quality dermatologic care to a diverse, underserved pediatric patient population while teaching trainees how to diagnose and manage common skin conditions. In our initial eight sessions, we served 37 patients, predominantly those with skin of color, and had a low no‐show rate of 9.8%. This report describes the general structure of the clinic, goals, and the patient population to provide an overview of our educational model for those interested in similar efforts.

Keywords: pediatric, dermatology, student clinic, teledermatology, education, underserved communities

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, we created a pediatric dermatology student‐run clinic. Our team had planned to launch an in‐person student‐run clinic in July 2020 with the dual objectives of providing dermatologic care to underserved children and introducing medical students to pediatric dermatology. However, due to the pandemic, institutions nationwide dramatically reduced in‐person outpatient dermatology office visits and consequently, educational opportunities for medical trainees. 1 , 2 The pandemic has also widened socioeconomic disparities and health care inequities. 3 Although teledermatology, in some cases and conditions, may be inferior to in‐person evaluation, 4 this alternative allows dermatologists and medical trainees to continue learning and providing dermatological care when in‐person opportunities are not available. When faced with COVID‐19‐related restrictions, our team pivoted to a virtual model of care. We describe the structure of the clinic, its operation, and its patient population in hopes of providing an educational model for those interested in similar efforts.

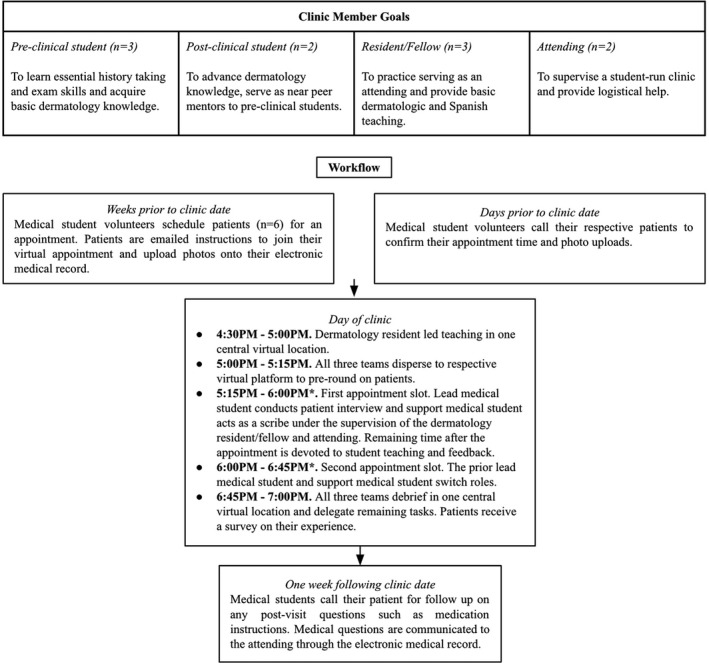

This monthly clinic is led by three teams composed of medical students, dermatology residents and fellows, and faculty, including one team fluent in Spanish (Figure 1). All team members commit to participation for at least one year. New patients with MassHealth, the Massachusetts public insurance program, with referrals from two local primary care clinics are identified and scheduled. Patients are asked to submit photographs in advance of the appointment. There are also clinic slots reserved for Spanish‐speaking patients, and all patients are asked if an interpreter is needed. Before clinic begins, there is dermatology teaching led by a resident, followed by a relevant Spanish lesson. After teaching, there are three parallel clinic sessions using a hospital‐approved virtual platform that provides real‐time interactive services. Over eight months, our student clinic has served 37 patients and managed 23 unique dermatologic conditions (Table 1). There was a 9.8% (n = 4/41) no‐show rate, compared to 30% in our internal dermatology department during this period.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of clinic member goals and workflow. *This is one of the first medical school patient interviews for our pre‐clinical volunteers and their first dermatology exposure under the direct supervision of the resident/fellow and attending. To ensure a high standard of dermatological care, we allocated a 45‐minute slot for each patient that included pre‐rounding preparation, thorough management discussion with the patient, and post‐visit teaching. This time allotment can be shortened for more experienced trainees

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Dermatologic Conditions of the Patients Seen in the Clinic from July 2020 to February 2021

| Patient demographics | N = 37 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age groups | |

| Age 0‐5 years | 16 (43.2%) |

| Age 6‐10 years | 7 (18.9%) |

| Age 11+ years | 14 (37.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (43.2%) |

| Female | 21 (56.8%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 2 (5.4%) |

| Black | 10 (27.0%) |

| Asian | 4 (10.8%) |

| Hispanic a | 15 (40.5%) |

| Other | 3 (8.1%) |

| Unknown/Not recorded | 3 (8.1%) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 24 (64.9%) |

| Spanish | 8 (21.6%) |

| Other | 5 (13.5%) |

| Dermatological findings | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 6 (13.0%) |

| Contact dermatitis | 6 (13.0%) |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 5 (10.9%) |

| Acne vulgaris | 4 (8.7%) |

| Birthmarks b | 3 (6.5%) |

| Molluscum contagiosum | 2 (4.3%) |

| Tinea capitis | 2 (4.3%) |

| Vitiligo | 2 (4.3%) |

| Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation | 2 (4.3%) |

| Other inflammatory conditions c | 6 (13.0%) |

| Other d | 8 (17.4%) |

Includes Black or other Hispanic. There were no White, Asian, Native American, or Native Hawaiian Hispanic.

These conditions included dermal melanocytosis, genetic syndromes, and congenital lacrimal fistula

These conditions included friction dermatitis, irritant diaper dermatitis, juvenile plantar dermatosis, keratosis pilaris, and pityrosporum folliculitis

These conditions included acanthosis nigricans, common acquired nevi, ganglion cyst, knuckle pad, lipoma, pyogenic granuloma, and telogen effluvium

There is a paucity of literature describing student‐run teledermatology clinics and best practices, and we have continually reflected on how to improve our clinic. One strategy that we believe has contributed to our very low no‐show rate—particularly for patients with language barriers—is having students call patients the day before clinic to confirm their appointment and answer any questions. Through frequent communication by medical students before, during, and after the clinic visit, this virtual model increases individualized attention to patients and may improve access to care. In turn, our diverse population serves as an enriching educational experience for medical students and residents for treating skin of color.

Due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, service and clinical learning opportunities have become limited. Our virtual student‐run dermatology clinic has provided a feasible way to care for underserved patients and provide early exposure for medical students to pediatric dermatology. More research is required to evaluate patient and student experiences with this clinic. Future plans include incorporation of in‐person visits and educational outreach to surrounding communities. We hope to disseminate our model and welcome inquiries from centers interested in serving this population and augmenting learning opportunities for medical trainees.

Danny Linggonegoro and Renajd Rrapi contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen Y, Pradhan S, Xue S. What are we doing in the dermatology outpatient department amidst the raging of the 2019 novel coronavirus? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, et al. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID‐19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. 2020;34(3 Suppl):1603‐1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okonkwo NE, Aguwa UT, Jang M, et al. COVID‐19 and the US response: accelerating health inequities. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020;bmjebm‐2020‐111426. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warshaw EM, Hillman YJ, Greer NL, et al. Teledermatology for diagnosis and management of skin conditions: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):759‐772.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.