Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the mechanism underlying the synergic interaction between Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)-associated ND1 and mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (YARS2) mutations.

Methods

Molecular dynamics simulation and differential scanning fluorimetry were used to evaluate the structure and stability of proteins. The impact of ND1 3635G>A and YARS2 p.G191V mutations on the oxidative phosphorylation machinery was evaluated using blue native gel electrophoresis and enzymatic activities assays. Assessment of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cell lines was performed by flow cytometry with MitoSOX Red reagent. Analysis of effect of mutations on autophagy was undertaken via flow cytometry for autophagic flux.

Results

Members of one Chinese family bearing both the YARS2 p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations exhibited much higher penetrance of optic neuropathy than those pedigrees carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation. The m.3635G>A (p.Ser110Asn) mutation altered the ND1 structure and function, whereas the p.191Gly>Val mutation affected the stability of YARS2. Lymphoblastoid cell lines harboring both m.3635G>A and p.191Gly>Val mutations revealed more reductions in the levels of mitochondrion-encoding ND1 and CO2 than cells bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation. Strikingly, both m.3635G>A and p.191Gly>Val mutations exhibited decreases in the nucleus-encoding subunits of complex I and IV. These deficiencies manifested greater defects in the stability and activities of complex I and complex IV and overproduction of ROS and promoted greater autophagy in cell lines harboring both m.3635G>A and p.191Gly>Val mutations compared with cells bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation.

Conclusions

Our findings provide new insights into the pathophysiology of LHON arising from the synergy between ND1 3635G>A mutation and mitochondrial YARS2 mutations.

Keywords: Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, ND1 gene, mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, mutations, oxidative phosphorylation

Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) have been associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), leading to severe visual impairment or even blindness due to the death of retinal ganglion cells.1–5 Among these mutations, the ND1 3460G>A, ND4 11778G>A, and ND6 14484T>C) mutations, which affect three core subunits of respiratory chain complex I (NADH dehydrogenase), accounted for the majority of LHON cases worldwide.6–11 Most recently, we identified the LHON-associated ND5 12338T>C and ND1 3394T>C, 3866T>C, and 3635G>A mutations in a large cohort of Han Chinese patients with LHON.12–14 The matrilineal relatives carrying the LHON-associated mtDNA mutations exhibited a wide range of phenotypic heterogeneity, including severity, age at onset, and penetrance of optic neuropathy.15–17 Biochemical analyses revealed that cells bearing the mtDNA mutations exhibited mild defects in complex I activity.18–20 The incomplete penetrance and gender bias in patients presenting with optic neuropathy suggest a role for the nuclear modifier genes in the phenotypic expression of LHON-associated mtDNA mutations.21 Our recent study demonstrated that several LHON families were manifested by synergic interaction between the m.11778G>A mutation and mutated modifiers YARS2 encoding mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase and X-linked modifier PRICKLE3 encoding a mitochondrial protein linked to biogenesis of ATPase.22,23 Notably, complex I deficiency impaired by biallelic mutations in DNAJC30 caused recessive Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy in 29 Caucasian families.24 However, the physiology of LHON remains poorly understood.

The m.3635G>A mutation caused a change of highly conserved serine at position 110 with asparagine (S110N) in ND1, the structural component of complex I.25,26 Therefore, the m.3635G>A mutation may alter both the structure and function of complex I, thereby causing mitochondrial dysfunction. The severity, age at onset, and penetrance of optic neuropathy among these families bearing the m.3635G>A mutation implicated the role of genetic modifiers in the phenotypic expression of m.3635G>A mutation.11,13 Sanger sequencing of the YARS2 gene identified the known variant (c.572G>T, p.191Gly>Val) in a three-generation Chinese family with higher penetrance of optic neuropathy. In this present study, we further investigated the impact of the m.3635G>A mutation on the structure and function of complex I. The functional consequences of the YARS2 p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations were further assessed with regard to the stability and activities of oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) complexes, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and autophagy through the use of lymphoblastoid mutant cell lines derived from members of the Chinese family (individuals carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191Gly>Val mutations), as well as genetically unrelated control subjects lacking these mutations.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Ophthalmological Examinations

A Han Chinese pedigree (WZ513) was recruited from the eye clinic of Zhejiang Provincial Eye Hospital, as described previously.11,13 A comprehensive history and physical examination for these participants were performed at length to identify personal medical histories of visual impairment and other clinical abnormalities. The ophthalmic examinations of family members were undertaken as detailed previously.11,12 The degree of visual impairment was defined according to the visual acuity as follows: normal, >0.3; mild, 0.3 to 0.1; moderate, <0.1 to 0.05; severe, <0.05 to 0.02; and profound, <0.02. This study was in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent, blood samples, and clinical evaluations were obtained from all participating family members under protocols approved by the ethic committee of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Sanger Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood of family members and control subjects by using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (51104; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The entire mitochondrial genomes of family members were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified in 24 overlapping fragments using sets of light-strand and heavy-strand oligonucleotide primers, and they were analyzed as described previously.27 Sanger sequence analyses of the YARS2 gene spanning five exons and flanking sequences from all family members were performed as detailed previously.22

Cell Cultures and Culture Conditions

Lymphoblastoid cell lines were immortalized by transformation with the Epstein–Barr virus, as described elsewhere.28 Patients who carried both m.3635G>A and homozygous YARS2 p.G191V mutations were identified as II-3 and II-6. Patients who were asymptomatic and carried both m.3635G>A and heterozygous p.G191V mutations were identified as III-4 and III-5. Patients harboring only the m.3635G>A mutation were identified as III-10 and III-11. Two genetically unrelated control individuals (C1 and C2) lacked these mutations and had the same mtDNA haplogroup (Supplementary Table S1). Cell lines derived from these patients were grown in RPMI 1640 Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The coordinates of wild-type ND1 were obtained from the cryo-electron microscopy (EM) structure of human mitochondrial respiratory complex I (Protein Data Bank [PDB] 5xtd).29 The positively charged residue K262 was treated as the deprotonated form, and the terminal residues were set to a charged state. The coordinates of S110N mutant were generated by the mutagenesis module of PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org), and protein–membrane systems were built using CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder (http://www.charmm-gui.org). A constant 50-mM NaCl was added to neutralize the system with 55,646 to 55,649 atoms, including the wild-type or mutant ND1 molecule, 180 palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) molecules, 8796 water molecules, seven Na+ molecules, and five Cl− molecules. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed with the GROMACS 4.5.5 package (https://www.gromacs.org/) utilizing CHARMM 36 force field.30 Energy minimization was performed to remove unfavorable steric clashes. In the equilibration steps, each system was gradually heated from 0 K to 310 K in two 25-ps NVT ensembles with positional constraints on the heavy atoms of the protein and phosphorus atoms of POPC. Each system was then equilibrated in 162.5-ns NPT ensembles with decreasing positional constraints at a temperature of 310 K and pressure of 1 bar. After equilibrations, the MD production were carried out for 100 ns with time steps of 2 fs. Electrostatics were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald method. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) curves were obtained using R 3.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The trajectory of each system was observed using visual molecular dynamics, and all molecular figures from simulations were obtained with PyMOL.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

The wild-type and mutant human YARS2 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned in-frame with a C-terminal His tag into the pET-28a vector. Recombinant wild-type and mutant YARS2 were produced as His tag fusion proteins in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3), as detailed elsewhere.31 The proteins were purified using a nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen). The stability of proteins was assessed using a Protein Thermal Shift dye kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and unfolding temperature (melting temperature, Tm) tests were performed on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the modified manufacturer's instructions. The data were analyzed as detailed elsewhere.32 The Tm value was estimated from the transition midpoint of the fluorescence curve, which corresponds to the temperature at which half of the protein population unfolded.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as detailed elsewhere.22,33 Twenty micrograms of cellular proteins was electrophoresed through 10% Bis-Tris SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The primary antibodies used for this experiment were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), including YARS2 (ab127542), ND1 (ab74257), CO2 (ab110258), TOM20 (ab56783), and total OXPHOS human WB antibody mixture (ab110411), and from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA), including NDUFS1 (12444-1-AP), NDUFA9 (20312-1-AP), NDUFS3 (15066-1-AP), SDHA (14865-1-AP), UQCRC1 (21705-1-AP), COX5A (11448-1-AP), ATP5B (17247-1-AP), and VDAC (55259-1-AP). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; AB-M-M 001) was obtained from Hangzhou Goodhere Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China), and light chain 3 (LC3; 4108) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG and Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used as a secondary antibody, and protein signals were detected using the ECL Western Blotting Analysis System (MilliporeSigma, Billerica, MA, USA). Quantification of density in each band was performed as detailed previously.22,33

Blue Native Gel Electrophoresis

Blue native gel electrophoresis was performed by isolating mitochondrial proteins from various cell lines, as detailed elsewhere.20,34 Samples containing 30 µg of mitochondrial proteins were separated on 3% to 11% Bis-Tris native polyacrylamide gel. The primary antibodies applied for this experiment were a totally human OXPHOS antibody cocktail with a voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) as a loading control. Alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) were used as secondary antibodies, and protein signals were detected using a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP)/nitro blue tetrazolium alkaline phosphatase color development kit (Beyotime).

Assays of Activities of OXPHOS Complex

The enzymatic activities of complexes I, II, III, and IV were assayed as described previously.11,35 Citrate synthase activity was analyzed by the reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) at 412 nm in the assay buffer containing 0.1-mM DTNB, 50-µM acetyl coenzyme A, 250-µM oxaloacetate, and 5 µg mitochondria. Complex I activity was analyzed by the decrease of decylubiquinone (DB) at 340 nm in the assay buffer including 130-µM NADH, 20-µM DB, and 10 µg mitochondria. Complex II was monitored by tracking the secondary reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) with DB at 600 nm in the assay buffer. Complex III activity was determined with the reduction of cytochrome c at 550 nm in the presence of 50-µM cytochrome c, 10-µM reduced decylubiquinone (DBH2), 1-mM n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DDM), and 5 µg mitochondria. The complex IV activity was measured through the oxidation of cytochrome c at 550 nm in the buffer containing 0.6 mg/mL, 450-µM DDM, and 5 µg mitochondria. All assays were performed using a Synergy H1 multifunctional microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Complex I to IV activities were normalized by citrate synthase activity, as detailed previously.35

ROS Measurements

MitoSOX Red reagent (excitation, 510 nm; emission, 580 nm in the FL-2 channel; Thermo Fisher Scientific) is a live-cell permeant that is rapidly and selectively targeted to the mitochondria. It can be oxidized by superoxide and exhibits red fluorescence when in the mitochondria. Lymphoblastoid cells were cultured in 5-mM MitoSOX Red reagent for 10 minutes at 37°C, then washed gently three times according to the modified manufacturer's instructions.14 The fluorescence signals of labeled cells were analyzed by a NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). A minimum of 10,000 cells were examined for each assay at a flow rate of <100 cells/s. Data were analyzed using FlowJo X (https://www.flowjo.com/).22,36

Flow Cytometry for Autophagic Flux

Lymphoblast cell lines were treated with a Cyto-ID Autophagy Detection Kit (ENZ-51031; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed twice with 1× assay buffer and stained with Cyto-ID at 37°C for 30 minutes while being protected from light. Cells were then washed again and analyzed by flow cytometry.20,37 The negative control and positive control cells were prepared using vehicle treatment or treatment in rapamycin and chloroquine.

Computer Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test contained in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). For each independent in vitro experiment, at least three technical replicates were used, and a minimum number of three independent experiments were performed to ensure adequate statistical power. In all of the analyses, group differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical Presentation and Mutation Analysis of YARS2 Gene in One Han Chinese Family

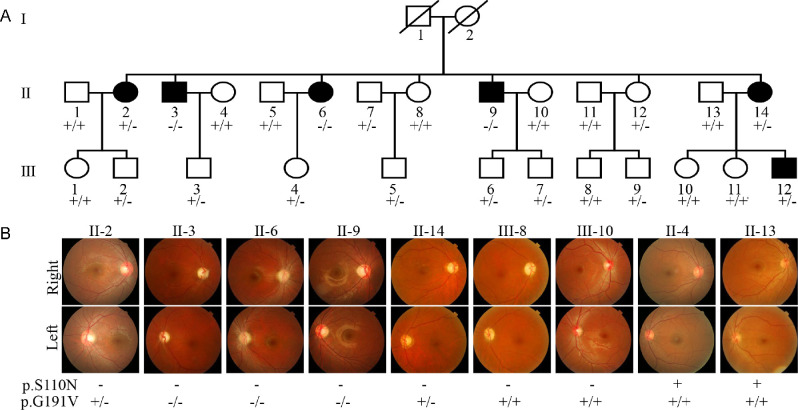

One Han Chinese family carrying the m.3635G>A mutation was identified among 1281 Chinese LHON probands, but it was absent in 478 Chinese vision-normal controls.11,13 As shown in Figure 1, the Chinese family exhibited relatively higher penetrance of vision impairment. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, six of 16 matrilineal relatives exhibited a variable degree of vision impairment (one with mild vision loss, one with moderate vision loss, two with severe vision loss, and two with profound vision loss), whereas none of other members in this family had vision impairment. The age at onset of vision impairment ranged from 14 to 28 years, with an average age of 18 years. There was no evidence that any of other members of this family had any other factor that would account for the visual impairment. These matrilineal relatives showed no other clinical abnormalities, including cardiac failure, muscular diseases, visual failure, and neurological disorders. Further analysis showed that the m.3635G>A mutation was present in homoplasmy in all matrilineal relatives but not in other members of this family (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Clinical and genetic characterization of one Chinese family. (A) LHON in three generations of a Han Chinese family. Vision-impaired individuals are indicated by black symbols. Individuals who harbored homozygous (–/–), heterozygous (+/–), or wild-type (+/+) YARS2 p.G191V mutations are indicated. (B) Fundus photographs (Cannon CR6-45NM) of Chinese patients, carriers, and control (married) subjects.

To test if the YARS2 mutation influenced the phenotypic manifestation of m.3635A>G mutation, we performed Sanger sequence analyses of the YARS2 gene spanning entire coding regions as detailed previously.22 Of these family members, the known homozygous YARS2 p.G191V nutation was present in three symptomatic matrilineal relatives, and the heterozygote YARS2 p.G191V nutation occurred in three symptomatic and five asymptomatic matrilineal relatives, as well as three members lacking the m.3635G>A mutation (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S2). These findings highlighted the role of the p.G191V nutation in the phenotypic expression of LHON-linked mtDNA mutations.

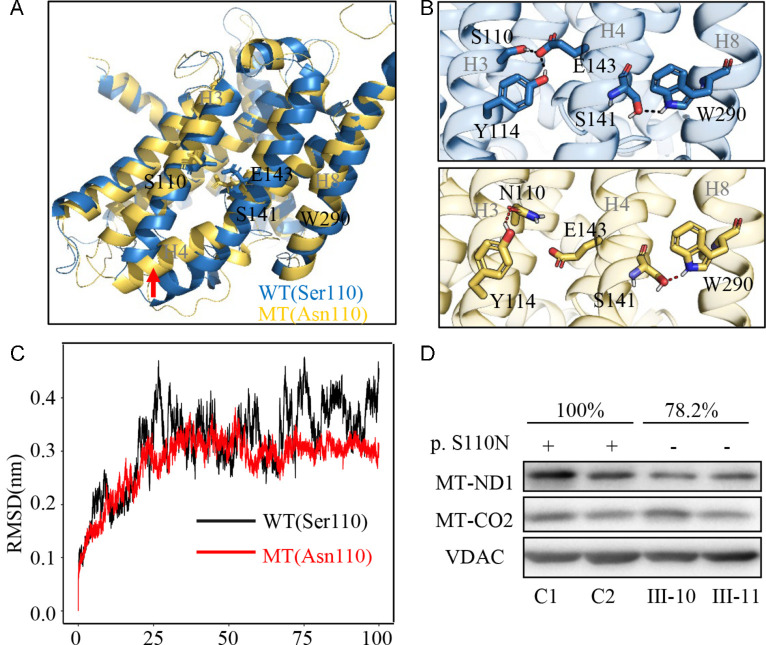

m.3635G>A Mutation Perturbed the Structure and Stability of ND1

To further evaluate the impact of m.3635 A>G mutation on the structure and stability of ND1, we performed MD simulation analyses. Based on the rational initial structure (PDB 5xtd),29 both wild-type (blue) and mutated (yellow) ND1 were evaluated by 100-ns all-atom MD simulations. As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, the local changes of conformation were induced by the absent interhelical interactions between the E143 in helix 4 (H4) and the S110 or Y114 in helix 3 (H3) when serine 110 was replaced by asparagine, whereas a new intrahelical interaction was formed by a new hydrogen bond between N110 and Y114 in H3. As shown in Figure 2C, the RMSD curve of ND1 with 110N has smoother fluctuations than that of ND1 with 110S, suggesting that the ND1 110N mutant molecule was less stable than the wild-type counterpart. These data indicated that m.3635G>A mutation perturbed the structure of ND1.

Figure 2.

Alterations in the structure and stability of ND1. (A–C) MD simulations on the ND1 protein were based on the cryo-EM structure of complex I from Homo sapiens (PDB 5xtd). (A) Superimposed images of the structures of wild-type (S110, blue) and mutant (N110, yellow) proteins at the end of the simulations. The red arrow indicates the bend of helix 4. (B) The electrostatic interactions formed between Ser110 and Glu143 in the wild-type protein (blue) and that between Asn110 and Tyr114 in the mutant protein (yellow). (C) Time evolution of the RMSD values of all Cα atoms for the wild-type (black lines) and mutant (red lines) proteins. (D) Western blot analysis; 5 µg of mitochondrial proteins from mutant cell lines (III-10, III-11) carrying the m.3635G>A mutation and control cell lines (C1, C2) lacking the mutation were electrophoresed through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted, and hybridized with ND1 and CO2 antibodies, with VDAC as a loading control, respectively.

To determine if the m.3635G>A mutation affects the stability of ND1, we examined the level of ND1 protein using western blot in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation and control cell lines lacking these mutations. As shown in Figure 2D, the level of ND1 in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A was 78.2% relative to the average values of control cell lines. However, there was no difference in the level of CO2 between mutant and control cell lines.

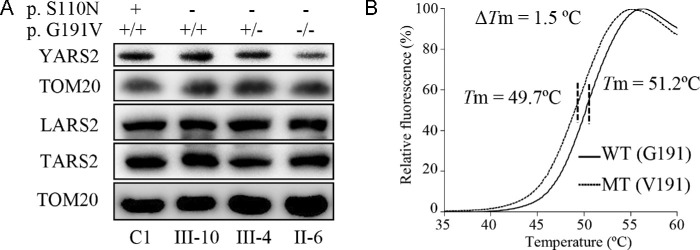

p.G191V Mutation Caused Instability of YARS2

To further examine the impact of p.G191V on the stability of YARS2, we analyzed the levels of YARS2 by western blot in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation, both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.G191V mutations, and one control cell line lacking these mutations. These blots were then hybridized with other nuclear encoding mitochondrial tRNA synthetases, LARS2 and TARS2, as well as Tom20 as a loading control. As shown in Figure 3A, the levels of YARS2 in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.G191V mutations were 99.5%, 79.9%, and 62.3%, respectively, relative to the average values of control cell lines. By contrast, the levels of LARS2 and TARS2 in the mutant cell lines were comparable with those in the control cell lines. These results strongly support the deleterious effect of p.G191V mutation on YARS2 structure.

Figure 3.

The instability of mutant YARS2 protein. (A) Western blot analysis; 5 µg of mitochondrial proteins from various cell lines were electrophoresed through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted and hybridized with YARS2, LARS2, and YARS2 antibodies with Tom20 as a loading control. (B) The thermal stability analysis of wild-type (G191) and mutant (V191) YARS2. ΔTm indicates the difference in melting temperature between wild-type (G191, solid line) and mutant (V191, dashed line) YARS2. The calculations were based on three to four determinations.

The effect of p.G191V mutation on the stability of YARS2 was also assessed using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). We used DSF to determine the Tm of YARS2, the temperature at which the concentration of folded protein is equivalent to that of unfolded protein. The fluorescence changes of the orange dye occurred in the presence of 1 µg of wild-type and mutated YARS2 over a temperature range from 25°C to 95°C. The thermal stability of mutant protein was compared with that of wild-type protein. As shown in Figure 3B, the Tm value of wild-type YARS2 was 51.2°C, whereas the Tm value of mutant YARS2 was 49.7°C. The lower thermal stability of mutant YARS2 protein than that of wild-type counterpart further supported that the p.G191V mutation led to the instability of YARS2 protein.

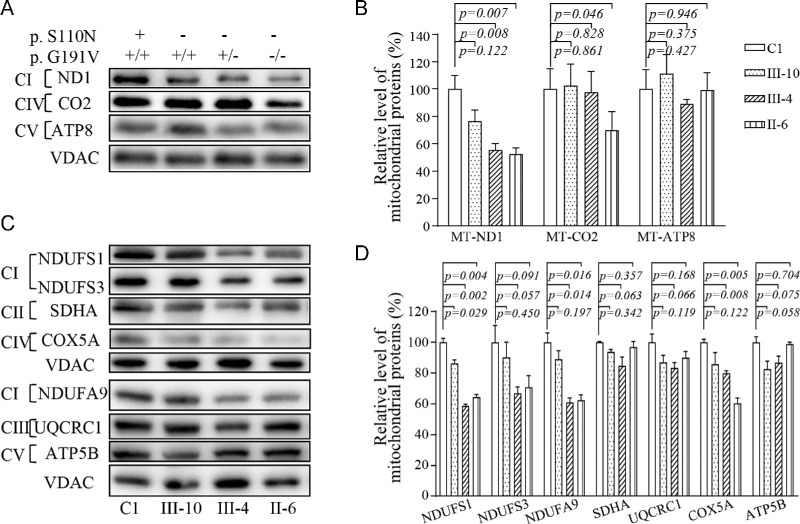

Reductions in Levels in the Subunits of OXPHOS

To assess if the p.G191V mutation worsened the deficient OXPHOS biogenesis associated with the m.3635G>A mutation, we performed a western blot analysis to examine the steady-state levels of nine subunits (mtDNA-encoding ND1, CO2, and ATP8 and six nucleus-encoding proteins) of OXPHOS in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation, both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations, and control cell lines lacking these mutations. As shown in Figures 4A and 4C, the p.191G>V mutation caused decreased levels of ND1, NDUFS1, NDUFS3, and NDUFA9 (subunits of NADH dehydrogenase). as well as CO2 and COX5A (subunits of cytochrome c oxidase), but did not affect the levels of the other four proteins (SDHA, QCRC1, ATP8, and ATP5B). As shown in Figure 4B, the levels of ND1 in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 76%, 55%, and 52%, respectively, of average levels of the control cell lines, whereas the levels of CO2 in these mutant cell lines were 102%, 97%, and 70%, respectively, of those in the control cell line. Strikingly, the levels of NDUFS1, NDUFS3, NDUFA9, and COX5A in the mutant cell lines bearing both m.3635G>A and homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 64.5%, 70.8%, 62.5%, and 60.4%, respectively, relative to the mean values measured in the control line. By contrast, the levels of these mitochondrial proteins in the mutant cell lines bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation were comparable with those in the control cell lines.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of mitochondrial proteins. (A, C) Twenty micrograms of total cellular proteins from various cell lines were electrophoresed through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted, and hybridized with antibodies for 10 subunits of OXPHOS (three encoded by mtDNA and seven encoded by nuclear genes), with VDAC as a loading control. (B, D) Quantification of levels of mitochondrial proteins: three mtDNA-encoding subunits (B) and seven nucleus-encoding subunits (D). The average content of each subunit was normalized to the average content of VDAC in the mutant and wild-type cell lines. The calculations were based on three independent determinations. The error bars indicate 2 SDs of the means. P indicates the significance (t-test) of the differences among the various cell lines.

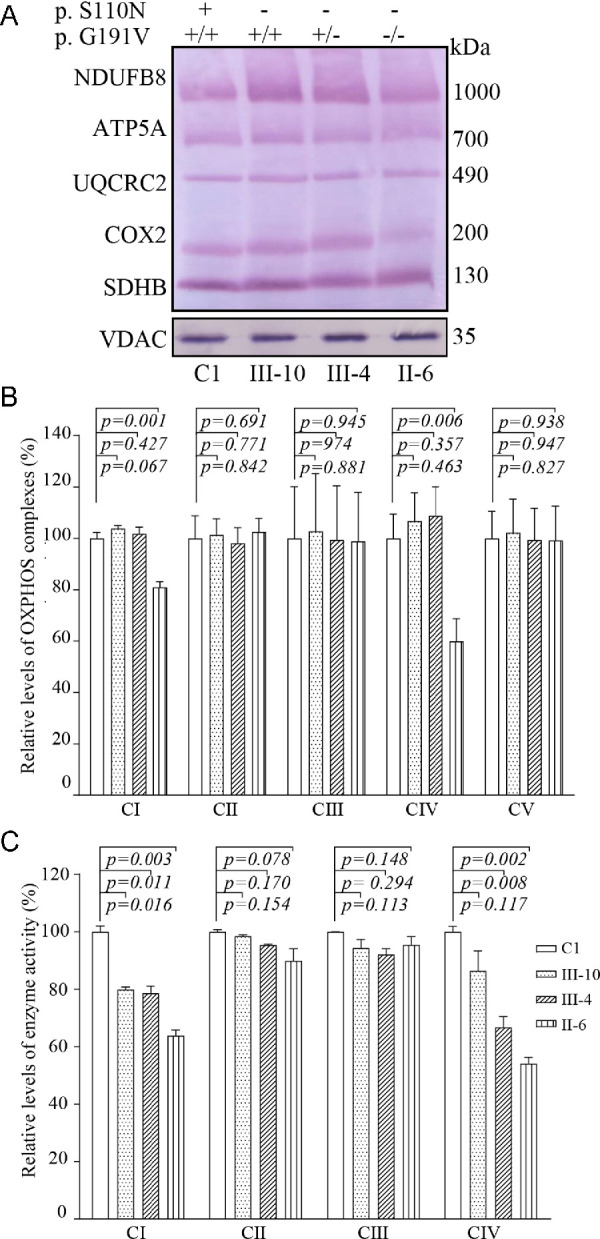

Defects in Stability and Activity of OXPHOS Complexes

We analyzed the consequence of m.3635G>A and p.G191V mutations on the oxidative phosphorylation machinery. Mitochondrial membrane proteins isolated from mutant and control cell lines were separated by blue native PAGE, electroblotting, and hybridizing with a human OXPHOS antibody cocktail consisting of NDUFB8, ATP5A, UQCRC2, CO2, and SDHB. As illustrated in Figure 5A, the mutant cell lines m.3635G>A and homozygous p.191G>V exhibited instability of complexes I and IV. As shown in Figure 5B, the levels of complexes I to V in the mutant cell lines (m.3635G>A and homozygous p.191G>V) were 80%, 102%, 98%, 59%, and 99%, respectively, of the average values in the control cell lines cells. However, the levels of these complexes in other mutant cell lines were comparable to those in the control cell lines.

Figure 5.

Defective stability and activities of complexes I and IV. (A) Blue native gel analysis of OXPHOS complexes, showing the steady-state levels of five OXPHOS complexes. Thirty micrograms of mitochondrial proteins from mutant and control cell lines were electrophoresed through a blue native gel, electroblotted, and hybridized with an antibody cocktail specific for the subunits of each OXPHOS complex, with VDAC as a loading control. (B) Quantification of levels of complexes I, II, III, IV, and V in mutant and control cell lines. The calculations were based on three independent experiments. (C) Enzymatic activities of OXPHOS complexes. The activities of respiratory complexes were investigated by enzymatic assay on complexes I, II, III, and IV in mitochondria isolated from various cell lines. The calculations were based on three independent experiments. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Figure 4.

We further measured the activities of respiratory chain complexes by isolating mitochondria from mutant and control cell lines as detailed elsewhere.20,35 As shown in Figure 5C, the activities of complex I in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 79%, 78%, and 63% of average levels of the control cell lines, respectively, whereas the activities of complex IV in these mutant cell lines were 86%, 66%, and 54%, respectively, of those in the control cell lines. However, the activities of complex II and III in these mutant cell lines were comparable to those in the control cell lines.

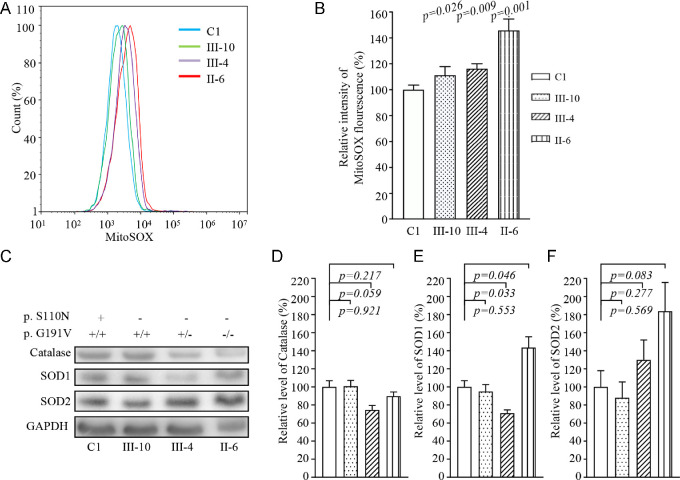

ROS Production Increase

Respiratory deficiency can increase the production of ROS.38 We assessed ROS production in mutant and control cell lines via flow cytometry, comparing baseline staining intensity for each cell line to that upon oxidative stress in order to obtain a ratio corresponding to ROS generation.36,39 Geometric mean intensity was recorded to measure the levels of mitochondrial ROS (mito-ROS) for each sample. The relative levels of geometric mean intensity in each cell line were calculated to delineate the levels of mito-ROS in mutant and control cells. As shown in Figures 6A and 6B, the levels of ROS generation in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 111.3%, 116.3%, and 145.8%, respectively, of the mean values measured in the control cell lines. Furthermore, we examined the levels of catalase and superoxide dismutase proteins (SOD1 and SOD2) in mutant and control cell lines by western blot analysis.20,38 Figures 7C and 7D show the variable levels of these proteins observed in the mutant cell lines as compared with those in the control cell lines. In particular, the levels of SOD2 in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 88%, 129%, and 183%, respectively, relative to the mean values measured in the control cell lines. The levels of SOD1 in these mutant cell lines were 92.5%, 103%, and 134%, respectively, of the average levels for the control cell line. However, slightly reduced levels of catalase in the cell lines harboring both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were observed, whereas there were no difference in catalase levels between control and cell lines bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation.

Figure 6.

Assays for mitochondrial ROS production. (A) Ratio of geometric mean intensity between levels of ROS generation in the vital cells. The rates of production in ROS from four cell lines were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer system with MitoSOX Red reagent (B) The relative ratio of intensity was calculated. The averages of three independent determinations for each cell line are shown. (C) Western blot analysis of antioxidative enzymes SOD2, SOD1, and catalase in six cell lines with GAPDH as a loading control. (D) Quantification of SOD2, SOD1, and catalase. Average relative values of SOD2, SOD1, and catalase were normalized to the average values of β-actin in various cell lines. The values for the latter are expressed as percentages of the average values for control cell line C1. The averages of three independent determinations for each cell line are shown. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Figure 4.

Figure 7.

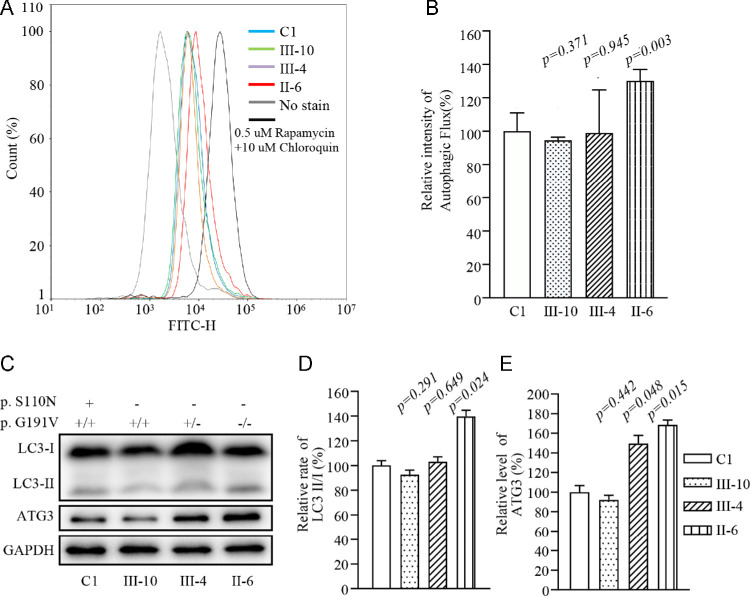

Analysis of autophagy. (A) Flow cytometry histograms showing fluorescence of various cell lines using a Cyto-ID Autophagy Detection Kit. Cells were incubated with RPMI 1640 medium in the absence and presence of rapamycin (inducers of autophagy) and chloroquine (lysosomal inhibitor) at 37°C for 18 hours. Then, Cyto-ID Green dye was added, followed by analysis with a NovoCyte flow cytometer. (B) Relative fluorescence intensity from various cell lines. Three independent determinations were made in each cell line. (C) Western blot analysis for autophagic response proteins LC3-I, LC3-II and ATG3. Twenty micrograms of total cellular proteins from various cell lines were electrophoresed, electroblotted, and hybridized with LC3 and ATG3 antibodies, with GAPDH serving as a loading control. (D) Quantification of autophagy markers LC3-II/I and ATG3 in mutant and control cell lines was carried out as described elsewhere.21 Three independent determinations were carried out in each cell line. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Figure 4.

Alteration in Autophagy

The alterations in OXPHOS and mitochondrial membrane potential affected the mitophagic removal of damaged mitochondria.20,40 To assess whether the m.3635G>A and p.G191V mutations regulated autophagy, the autophagic states of various mutant and control cell lines were analyzed using both fluorescence-based cytometry and western blot assays. First, Cyto-ID Autophagy Detection Kits were used with flow cytometry to examine the degree of autophagy of mutant and control cell lines. As shown in Figures 7A and 7B, significant shifts in the fluorescence peak to high intensity occurred in the mutant cell lines harboring both m.3635G>A and homozygous p.191G>V mutations, as compared with those in the control cell lines. The levels of autophagy in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 94%, 99%, and 130%, respectively, of the mean values measured in the control cell lines. To further evaluate the effect of these mutations on mitophagy, we performed a western blot analysis using two markers: microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3B) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme for the LC3 lipidation process (ATG3) in various cell lines.41,42 As shown in Figures 7C and 7D, the average levels of LC3II/I+II in the mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 92.5%, 103.0%, and 139.9%, respectively, of the mean values measured in the control cell lines. Furthermore, the average levels of ATG in the mutant cell lines harboring only the m.3635G>A mutation or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous or homozygous p.191G>V mutations were 92.1%, 149.5%, and 168.6%, respectively, of the mean values measured in the control cell lines.

Discussion

In this study, we further investigated the molecular mechanism of the LHON-associated ND1 3635G>A mutation. Indeed, the occurrence of the m.3635G>A mutation in these genetically unrelated pedigrees affected by LHON from different ethic backgrounds strongly suggest that this mutation is involved in the pathogenesis of LHON.11,13,43–45 The m.3635G>A (p.S110N) mutation changed a serine at position 110 with asparagine in ND1, which is an essential subunit of complex I.25,46 Complex I is composed of 45 subunits, including seven subunits encoded by mtDNA and 38 subunits encoded by nuclear genes.25 Based on MD stimulation data, serine 110 being replaced by asparagine induced a new intrahelical interaction between N110 and Y114 in H3 in the ND1 structure, suggesting that the 3635G>A mutation altered structure and function of complex I.25,46 In this investigation, the instability of mutated ND1 was further evidenced by the reduced levels of ND1 observed in mutant cell lines bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation. The instability of ND1 were responsible for 20% reductions in the activity of complex I observed in mutant cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation, as in the cases of cell lines bearing LHON-associated m.3866T>C and m.3394T>C mutations.20,47 The respiratory deficiency resulted in decreased efficiency of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and increased the generation of ROS.13,14 However, the low penetrance of LHON and mild mitochondrial dysfunction strongly suggests that the m.3635G>A mutation is the primary contributor to the development of LHON but is insufficient to produce a clinical phenotype.

Nuclear modifier genes were proposed to modulate the phenotypic manifestation of the LHON-associated mtDNA mutations.21–23 In this study, the penetrance of LHON in the Chinese family harboring both m.3635G>A and YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations was significantly higher than in other families carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation.11,13 The Gly191 residue lies within the catalytic domain of YARS2, which interacts with the base-pairing (1G-72C) of tRNATyr acceptor stem.48 Thus, the p.191Gly>Val mutation affected the structure and function of this enzyme. The p.Gly191Val mutation resulted in the instability of YARS2, as evidenced by the reduced level of mutant protein revealed by western blot analysis and the thermal instability observed by DSF. In vitro assays showed that the p.G191Asp mutation reduced enzymatic activity.49 YARS2 deficiencies altered aminoacylation of tRNATyr and impaired the synthesis of 13 mtDNA-encoding OXPHOS subunits.22,49,50 The reduced levels among the 13 mtDNA-encoding OXPHOS subunits in the cells bearing the YARS2 mutations were correlated with the tyrosine codon usage of polypeptides, with especially pronounced effects in the subunits with higher tyrosine codon content such as ND1, ND4, ND5, ND6, CO1, and CO2.22,49,51–53 In the present study, more drastic reductions in the level of ND1 were observed in the cell lines bearing both m.3635G>A and homozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations than in cells harboring both m.3635G>A and heterozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val or only the m.3635G>A mutation. Notably, the levels of CO2 in these mutant cell lines bearing both m.3635G>A and homozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations, both m.3635G>A and heterozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations, or only the m.3635G>A mutation were 102%, 97%, and 70%, respectively, of those in the control cell line. The discrepancy in ND1 and CO2 expression levels between cells bearing both m.3635G>A and homozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations or both m.3635G>A and heterozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations may also be due to tRNA codon preference. In contrast with the cell lines harboring only the m.3635G>A mutation, mutant cell lines harboring both m.3635G>A and p.191Gly>Val mutations exhibited significant decreases of nucleus-encoding NDUFS1, NDUFS3, and NDUFA9 (subunits of complex I) and COX5A (subunit of complex IV), as in the case of YARS2-knockout cell lines.50 These deficiencies resulted in the instability and decreased activity of complexes I and IV in cell lines bearing both m.3635G>A and homozygous YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutations, in contrast with mild defects in complex I in cell lines bearing only the m.3635G>A mutation. These respiratory deficiencies were responsible for more drastic increases of ROS production in the cell lines carrying both p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations than in cell lines carrying only p.191Gly>Val or m.3635G>A mutations.13,53

The impairment of OXPHOS affects the mitophagic removal of damaged mitochondria.20,54–56 In this study, we showed that cell lines carrying both carrying both p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations exhibited higher levels of autophagy than the cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation. Furthermore, more severe decreases levels of ATG2 were observed in cybrid cell lines carrying both p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations than in cell lines carrying only the m.3635G>A mutation, which suggests a greater decrease in the capacity of double mutant cells to generate autophagoeomes, thereby perturbing the autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated proteins.42,56 These data indicate that the p.191Gly>Val mutation worsened the defective autophagy caused by the m.3635G>A mutation. Therefore, the YARS2 p.191Gly>Val mutation aggravated the biochemical defects caused by the m.3635G>A mutation, including the defective activity of complexes I and IV, a decrease in mitochondrial ATP production, overproduction of ROS, and the promotion of autophagy.13,20,47 These mitochondrial dysfunctions yielded a preferential effect on the photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cells in the retina, because rental functions depend on a very high rate of ATP production.57,58 The result is dysfunction or death of photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cells in the retina carrying both p.191Gly>Val and m.3635G>A mutations, thereby producing a phenotype of vision impairment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their family members for participation.

Supported by a grant from the National Key R&D Program of China, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018YFC1004802), and grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (31970557 31471191, 81400434, and 81900904).

Disclosure: X. Jin, None; J. Zhang, None; Q. Yi, None; F. Meng, None; J. Yu, None; Y. Ji, None; J.Q. Mo, None; Y. Tong, None; P. Jiang, None; M.-X. Guan, None

References

- 1. Wallace DC, Lott MT.. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: exemplar of an mtDNA disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol . 2017; 240: 339–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howell N. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: respiratory chain dysfunction and degeneration of the optic nerve. Vision Res. 1998; 38: 1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sadun AA, La Morgia C, Carelli V. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol . 2011; 1391: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Hudson G, Chinnery PF.. Inherited mitochondrial optic neuropathies . J Med Genet. 2009; 46: 145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carelli V, La Morga C, Valentino ML, Barboni P, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA. Retinal ganglion cell neurodegeneration in mitochondrial inherited disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta . 2009; 1787: 518–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, et al.. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Science . 1988; 24: 1427–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruiz-Pesini E, Lott MT, Procaccio V, et al.. An enhanced mitomap with a global mtDNA mutational phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res . 2007; 35: D823–D828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown MD, Torroni A, Reckord CL, Wallace DC.. Phylogenetic analysis of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mitochondrial DNA's indicates multiple independent occurrences of the common mutations. Hum Mutat . 1995; 6: 311–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang P, Liang M, Zhang J, et al.. Prevalence of mitochondrial ND4 mutations in 1281 Han Chinese subjects with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2015; 56: 4778–4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liang M, Jiang P, Li F, et al.. Frequency and spectrum of mitochondrial ND6 mutations in 1218 Han Chinese subjects with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2014; 55: 1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ji Y, Liang M, Zhang J, et al.. Mitochondrial ND1 variants in 1281 Chinese subjects with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2016; 56: 2377–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou X, Qian Y, Zhang J, et al.. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy is associated with the T3866C mutation in mitochondrial ND1 gene in three Han Chinese families . Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2012; 53: 4586–4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Jiang P, Jin X, et al.. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy caused by the homoplasmic ND1 G3635GA mutation in nine Han Chinese families. Mitochondrion. 2014; 18: 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang J, Ji Y, Lu Y, et al.. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)-associated ND5 12338T>C mutation altered the assembly and function of complex I, apoptosis and mitophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2018; 27: 1999–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Newman NJ, Lott MT, Wallace DC.. The clinical characteristics of pedigrees of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy with the 11778 mutation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991; 111: 750–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riordan-Eva P, Sanders MD, Govan GG, Sweeney MG, Dacosta J, Harding AE.. The clinical features of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy defined by the presence of a pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutation. Brain. 1995; 118: 319–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhou X, Zhang H, Zhao F, et al.. Very high penetrance and occurrence of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy in a large Han Chinese pedigree carrying the ND4 G11778A mutation. Mol Genet Metab. 2010; 100: 379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brown MD, Trounce IA, Jun AS, Allen JC, Wallace DC.. Functional analysis of lymphoblast and cybrid mitochondria containing the 3460, 11778, or 14484 Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mitochondrial DNA mutation. J Biol Chem . 2000; 275: 39831–39836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hofhaus G, Johns DR, Hurkoi O, Attardi G, Chomyn A.. Respiration and growth defects in transmitochondrial cell lines carrying the 11778 mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. J Biol Chem . 1996; 271: 13155–13161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ji Y, Zhang J, Lu Y, et al.. Complex I mutations synergize to worsen the phenotypic expression of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. J Biol Chem. 2020; 295: 13224–13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bu XD, Rotter JI.. X chromosome-linked and mitochondrial gene control of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: evidence from segregation analysis for dependence on X chromosome inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991; 88: 8198–8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiang P, Jin X, Peng Y, et al.. The exome sequencing identified the mutation in YARS2 encoding the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase as a nuclear modifier for the phenotypic manifestation of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy-associated mitochondrial DNA mutation. Hum Mol Genet . 2016; 25: 584–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu J, Liang X, Ji Y, et al.. PRICKLE3 linked to ATPase biogenesis manifested Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. J Clin Invest. 2020; 130: 4935–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stenton SL, Sheremet NL, Catarino CB, et al.. Impaired complex I repair causes recessive Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. J Clin Invest . 2021; 131: e13826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scheffler IE. Mitochondrial disease associated with complex I (NADH-CoQ oxidoreductase) deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015; 38: 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu J, Vinothkumar KR, Hirst J.. Structure of mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature. 2016; 536: 354–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rieder MJ, Taylor SL, Tobe VO, Nickerson DA.. Automating the identification of DNA variations using quality-based fluorescence re-sequencing: analysis of the human mitochondrial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998; 26: 967–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller G, Lipman M.. Release of infectious Epstein-Barr virus by transformed marmoset leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973; 70: 190–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo R, Zong S, Wu M, Gu J, Yang M.. Architecture of human mitochondrial respiratory megacomplex I2III2IV2. Cell. 2017; 170: 1247–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang J, MacKerell AD Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J Comput Chem. 2013; 34: 2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meng F, Cang X, Peng Y, et al.. Biochemical evidence for a nuclear modifier allele (A10S) in TRMU (methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate-methyltransferase) related to mitochondrial tRNA modification in the phenotypic manifestation of deafness-associated 12S rRNA mutation. J Biol Chem. 2017; 292: 2881–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M.. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. NatProtoc. 2007; 2: 2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gong S, Peng Y, Jiang P, et al.. A deafness-associated tRNAHis mutation alters the mitochondrial function, ROS production and membrane potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42: 8039–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jha P, Wang X, Auwerx J.. Analysis of mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BNPAGE). Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2016; 6: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Birch-Machin MA, Turnbull DM.. Assaying mitochondrial respiratory complex activity in mitochondria isolated from human cells and tissues. MethodsCellBiol. 2001; 65: 97–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jiang P, Wang M, Xue L, et al.. A hypertension-associated tRNAAla mutation alters tRNA metabolism and mitochondrial function. Mol Cell Biol. 2016; 36: 1920–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ho TT, Warr MR, Adelman ER, et al.. Autophagy maintains the metabolism and function of young and old stem cells. Nature. 2017; 543: 205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayashi G, Cortopassi G.. Oxidative stress in inherited mitochondrial diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015; 88A: 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mahfouz R, Sharma R, Lackner J, Aziz N, Agarwal A. Evaluation of chemiluminescence and flow cytometry as tools in assessing production of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion in human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92: 819–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma LK, Tiwari M, Rai NK, Bai Y.. Mitophagy activation repairs Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy-associated mitochondrial dysfunction and improves cell survival. Hum Mol Genet. 2019; 28: 422–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Korolchuk VI, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC.. A novel link between autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Autophagy. 2009; 5: 862–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tanida I, Tanida-Miyake E, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Kominami E.. Human Apg3p/Aut1p homologue is an authentic E2 enzyme for multiple substrates, GATE-16, GABARAP, and MAP-LC3, and facilitates the conjugation of hApg12p to hApg5p. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 13739–13744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kodrol A, Krawczylski MR, Tolska K, Bartnik E. m.3635G>A mutation as a cause of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. J Clin Pathol. 2014; 67: 639–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bi R, Zhang AM, Jia X, Zhang Q, Yao YG.. Complete mitochondrial DNA genome sequence variation of Chinese families with mutation m.3635G>A and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Mol Vis. 2012; 18: 3087–3094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Starikovskaya E, Shalaurova S, Dryomov S, et al.. Mitochondrial DNA variation of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy in Western Siberia. Cells. 2019; 8: 1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zickermann V, Wirth C, Nasiri H, et al.. Structural biology. Mechanistic insight from the crystal structure of mitochondrial complex I. Science. 2015; 347: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ji Y, Zhang J, Yu J, et al.. Contribution of mitochondrial ND1 3394T>C mutation to the phenotypic manifestation of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Hum Mol Genet . 2019; 28: 1515–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bonnefond L, Frugier M, Touze E, et al.. Crystal structure of human mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase reveals common and idiosyncratic features. Structure. 2007; 15: 1505–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Riley LG, Menezes MJ, Rudinger-Thirion J, et al.. Phenotypic variability and identification of novel YARS2 mutations in YARS2 mitochondrial myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anaemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013; 8: 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jin X, Zhang Z, Nie Z, et al.. An animal model for mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency reveals links between oxidative phosphorylation and retinal function. J Biol Chem. 2021; 296: 100437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Riley LG, Cooper S, Hickey P, et al.. Mutation of the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase gene, YARS2, causes myopathy, lactic acidosis, and sideroblastic anemia–MLASA syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010; 87: 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sasarman F, Nishimura T, Thiffault I, Shoubridge EA.. A novel mutation in YARS2 causes myopathy with lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia. Hum Mutat. 2012; 33: 1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fan W, Zheng J, Kong W, et al.. Contribution of a mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase mutation to the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated tRNASer(UCN) 7511A>G mutation. J Biol Chem. 2019; 294: 19292–19305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee J, Giodano S, Zhang J.. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signaling. BiochemJ. 2012; 44: 523–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang J, Liu X, Liang X, et al.. A novel ADOA-associated OPA1 mutation alters the mitochondrial function, membrane potential, ROS production and apoptosis. SciRep. 2017; 7: 5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Skeie JM, Nishimura DY, Wang CL, et al.. Mitophagy: an emerging target in ocular pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021; 62: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Country MW. Retinal metabolism: a comparative look at energetics in the retina. Brain Res . 2017; 1672: 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wong-Riley MT. Energy metabolism of the visual system. Eye Brain . 2010; 2: 99–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.