Abstract

Objective:

To review the signs and symptoms of feeding difficulties in children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorders and provide practical advice, with the goal of guiding the practitioner to timely referral for further evaluation and therapy. Various management approaches are also discussed.

Data Sources:

Articles and chapters related to normal feeding patterns and the diagnosis and management of feeding difficulties in children were reviewed.

Study Selections:

Selections were based on relevance to the topic and inclusion of diagnostic and management recommendations.

Results:

Because most non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorders occur in early childhood, feeding skills can be disrupted. Feeding difficulties can result in nutritional deficiencies, faltering growth, and a significant impact on quality of life. Specific symptoms related to each non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorder can lead to distinctive presentations, which should be differentiated from simple picky eating. Successful management of feeding difficulties requires that the health care team views the problem as a relational disorder between the child and the caregiver and views its association with the symptoms experienced as a result of the non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorder. Addressing the child’s concern with eating needs to be done in the context of the family unit, with coaching provided to the caregiver as necessary while ensuring nutritional adequacy. Treatment approaches, including division of responsibility, food chaining, and sequential oral sensory, are commonly described in the context of feeding difficulties.

Conclusion:

A multidisciplinary approach to management of feeding difficulties in non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorders is of paramount importance to ensure success.

Introduction

Food allergies can involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in various ways. IgE-mediated food allergies typically cause nausea and vomiting, which can occur almost immediately after ingestion of the culprit food, often while the food is still being consumed, and/or diarrhea, which may occur promptly or may be delayed by several hours.1 In contrast, non–IgE-mediated food allergic reactions are more delayed. They occur with repetitive exposure to the culprit food(s) and typically result in chronic inflammation that affects various parts of the GI tract with associated symptoms (Table 1). Non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders encompass a number of diseases, namely eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs), food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), food protein–induced proctocolitis (FPIP), and other less well-defined non–IgE-mediated food protein–induced allergic dysmotility disorders that result in GI symptoms.5

Table 1.

Common Feeding Difficulties Resulting From Symptoms Caused by Each Non–IgE-Mediated Food Allergic Gastrointestinal Disorder

| NoneIgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorder | Symptoms associated with the development of feeding difficulties | Common presenting feeding difficulty |

|---|---|---|

| EoE | Vomiting, abdominal pain, dysphagia, early satiety, faltering growth | Fear of eating (ie, fear of swallowing or food stuck in the esophagus, possible pain with eating) |

| Selective eating (ie, selective about textures) Limited appetite and food refusal (ie, consume small amounts) | ||

| EGIDs besides EoE | Vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea | Fear of eating (ie, fear of abdominal pain and discomfort) Selective eating (ie, selective about texture) |

| Limited appetite (ie, attributable to dysmotility that affects appetite and satiety) | ||

| FPIES | Acute vomiting, shock | Fear of eating (ie, concern of further reactions) |

| Selective eating (ie, limiting variety of food because of fear of new reactions) | ||

| FPIP | Blood in the stool | Parental fear of feeding |

| Food proteineinduced allergic dysmotility disordersa | Vomiting, diarrhea, constipation,b faltering growth | Fear of feeding |

| Selective intake | ||

| Limited appetite | ||

Abbreviations: EGIDs, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; FPIES, food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome, FPIP, food protein–induced proctocolitis.

This includes dysmotility conditions that can be food protein induced, including gastroesophageal reflux disease2 and constipation.3,4

Should only be considered in food allergy if associated with other atopic symptoms and if standard dietary and medical management is not effective.

EGIDs can occur at any age and include several subsets that are named after the location they affect in the GI tract. These conditions are eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic enteritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis. Symptoms of EoE in children are mostly nonspecific and include abdominal pain, vomiting, and gastroesophageal reflux but can also include dysphagia and esophageal food impactions. The remaining EGIDs cause abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea, with blood in the stool also occurring in some patients with colitis.6 FPIES, FPIP, and food protein–induced allergic dysmotility disorders affect children more commonly during infancy. Although FPIES can cause nonspecific GI symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea) and failure to thrive in the chronic phase, children with acute FPIES can experience shock in the event of reexposure to the culprit food after a period of avoidance.7 FPIP is the least severe of the non–IgE-mediated food allergies of the gut because infants with FPIP are typically healthy besides having blood in their stools on most occasions.8 Food protein–induced allergic dysmotility disorders, which can cause gastroesophageal reflux, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, have been reported in particular with cow’s milk allergy2–4,9 but can also occur with other food allergens, such as soy, egg, and wheat.10,11 All the non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders discussed here can be successfully managed with the avoidance of the trigger food(s) as demonstrated by clinical and histopathologic remission.12

Non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders can negatively affect a child’s feeding skills and ability, depending on the associated symptoms, severity of the disease, the age at which the child is affected, social circumstances, and the degree of dietary restriction therapy used. Early diagnosis and management of these feeding difficulties are of paramount importance because they can result in nutritional deficiencies or growth faltering.

Studies estimate that feeding difficulties may be present in 25% or even up to 50% of normally developing children.13,14 Between 30% and 80% of children with developmental delays have been reported to have feeding difficulties.15 Mukkada et al16 reported that up to 94% of children with EGIDs have feeding difficulties. Given this high rate of reporting, the practitioner as well as the primary caregiver can have a difficult time deciphering what is part of normal development and what may require further evaluation.

Normal Feeding Development

At birth, term infants demonstrate suck, swallow, and gag reflexes that allow them to feed immediately. They are able to coordinate suck-swallow-breathe during breast or bottle-feeding. Suckling is highly automatic and reflexive during that stage. By 4 months of age, suck-swallow becomes more voluntary. Liquid intake from a cup can start at that age. Between 12 and 18 months of age, a child may still rely on biting the edge of the cup to stabilize the jaw, but by 15 months of age most infants can drink from a cup without help.17,18

Solid foods, usually in pureed form, are typically introduced between 4 and 6 months of age. At this age, infants can open their mouth for a spoon, use their tongue to move the food bolus to the back of their mouth to swallow it, and keep the food in their mouth. Oral function progresses to a bite-and-release pattern at 5 to 6 months of age. By 7 months of age, they can close their lip on the spoon and use their upper lip to clear the spoon, and most can remove food from the spoon with their lips by 12 months of age. Sustained biting and the beginning of rotary chewing are typically seen at 9 to 12 months of age. If all goes well, a child will progress with food textures from purees to ground or mashed and then chopped table foods. At 7 to 8 months of age, most infants can grasp food with their hands and begin self-feeding. Although most infants can hold food in their hand and have begun trying to hold a spoon at 8 months of age, most can feed themselves with a spoon without much spilling by 19 to 24 months of age. Between 8 and 12 months, children can bite crunchier foods as their teeth erupt, and by 15 months of age most children have the ability to chew food. As chewing continues to mature, most show interest in a large variety of textures without gagging.17,18 Those offered more solid textures at 6 months of age have better chewing skills by 12 months of age.17 In addition, they are more accepting of, and are able to adequately chew, most table foods by 2 years of age.17 There seems to be a critical period when infants are most receptive to different food textures. Infants who were introduced to lumpy foods after 9 months of age have been observed to demonstrate a highly selective pattern and exhibited more feeding problems by 7 years of age.19

Not only is the oral-motor system progressive and critical, but oral sensory development also follows very specific temporal milestones. The extent to which food flavors are liked or disliked is determined by innate factors, nutritional interventions, and learning.20 Infants get exposed to a variety of food flavors that their mothers ingest via amniotic fluid, and if they are breastfed, via breast milk. These exposures influence their flavor preferences shortly after birth and at weaning.20 These varied sensory experiences with food flavors help explain why breastfed infants are more willing to try new foods.21 In nonbreastfed children with food allergy, hypoallergenic formulas are required, and data indicate that infants younger than 2 months have willingness to drink a bitter and sour protein hydrolysate formula, whereas 7- to 8-month-old infants rejected it.22 The experiences with the formula flavor affected their preferences for food taste qualities later on during weaning.23 Infants feeding protein hydrolysate formulas, which are typically bitter and sour, preferred savory, bitter, and sour cereals much more than those fed intact cow’s milk–based formulas.23 These flavor preferences were present even at 11.5 years of age.24

Where and When Feeding and Eating Could Go Wrong

Feeding skills, including oral-motor, sensory, behavioral or emotional, and communication skills, develop early, and disruption of this process caused by symptoms related to the non–IgE-mediated GI disease, or by the dietary interventions, can create feeding difficulties.25

Levy et al26 established common triggers for feeding difficulties in children, including size (faltering growth), transitioning (puree to lumpier textures), organic disease (including GI disorders), mechanistic feeding (ignoring absent hunger cues), and posttraumatic event (traumatic event around feeding, including choking and violent vomiting). In non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders, most of these triggers are present in the well-documented symptoms (Table 1). Faltering growth is a common presenting symptom, with low weight and in particular low height found in approximately 10% of children with this diagnosis.27 Poor growth often leads to heightened parental anxiety around feeding as well as a mechanistic feeding pattern, with hunger and satiety ignored to enable more food intake.28 Non–IgE-mediated allergic GI symptoms, including gastroesophageal reflux, abdominal pain, and constipation, are also associated with feeding difficulties.29,30 Of these difficulties, frequent vomiting has been best described as having a negative impact, in particular on children with EoE.30–32 Constipation and abdominal pain in non–IgE-mediated GI allergies have also been associated with feeding difficulties.29 It is hypothesized that through visceral hypersensitivity that affects visceral pain pathways, sensory perception is affected, as was the case in other pediatric chronic diseases that led to feeding difficulties.33 Chronic pain or discomfort also affects the willingness to eat and explore new foods, affecting the development of oral-motor skills and sensory perception of food.34 Non–IgE-mediated allergic GI conditions can also affect motility,35 which in turn may alter appetite and satiety, which then feeds into compensatory feeding. Finally, events such as violent vomiting in acute FPIES or dysphagia and esophageal food impactions in EoE can be traumatic for parents as well as the child. Once triggers have been identified, it is useful to be able to classify the feeding difficulty according to the universal classification by Kerzner et al,36 which includes children with limited appetite, those with selective intake, and children with a fear of feeding (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of Feeding Difficulty With Suggested Corresponding Therapeutic Strategies

| Type of feeding difficulty | Therapy strategy | Practical points |

|---|---|---|

| Limited appetite | Division of responsibility | When mealtimes will be served |

| Portions that are served | ||

| What foods are served | ||

| Mutual trust in regard to what is offered and what is consumed | ||

| Selective intake | Food chaining SOS approach | Establish the sensory characteristics of food and introduce new foods in a sequential way |

| Ensure that children have the correct seating/mealtime environment | ||

| Offer advice on oral motor skill development | ||

| Dispel myths about normal eating | ||

| Fear of feeding | Division of responsibility SOS approach | When mealtimes will be served |

| Portions that are served | ||

| What foods are served | ||

| Mutual trust in regard to what is offered and what is consumed | ||

| Interpretation of pain and discomfort | ||

Abbreviation: SOS, sequential oral sensory.

Not only can symptoms be associated with feeding difficulties, but also overly restricted dietary therapies implemented for many of the non–IgE-mediated diseases during critical phases of feeding developmental progression can lead to a limited range of textures and flavor exposure. This in turn can lead to an arrest in the development of proper oral-motor and sensory functions.32

In addition, the behavioral aspects of feeding should be remembered. Rommel et al30 found that medical and oral-motor causes are mainly to blame for feeding difficulties at younger than 2 years, and above that age, feeding behavior is a more common problem. In non–IgE-mediated GI allergies, dietary avoidance is the mainstay for management, which entails careful product selection and food preparation. Children also learn to eat through parental modeling. Therefore, essential allergen-free product selection and reluctance to introduce new foods because of fear of a reaction can easily be adopted by children who then become very selective in their intake.37 Food neophobia (fear of trying a new food) is a normal occurrence in early childhood when a child wants to be independent, which can have a further negative effect on feeding.38,39

Diagnostic Approach for Feeding Difficulties

Picky eating should be differentiated from a pathological problem. Parents or caregivers often report that their children are “picky” some or most of the time. Toddlers may eat less than before. They are opinionated, skeptical, and erratic when they eat; they are fickle, cautious, messy, and picky. Some days, they would rather play than eat. Toddlers have a lot to learn about food and how to eat. Preschoolers are often less skeptical about new food and should be more willing to try it. They often wiggle and squirm when they sit at the table and cannot be fooled by hiding vegetables in foods. During the school-age years, children want to practice grown-up skills, and they grow more confident in their ability to feed themselves. They will often use utensils but may still use their fingers from time to time. The list of foods they are willing to eat on a regular basis is getting longer. Adolescents can be described as toddlers with attitude and can be just as erratic as toddlers with their mood. The physical changes that occur in adolescents may make them self-conscious, and their appetites can increase notably. Food choices may change based on many factors, including peer pressure or environmental effect.40

Picky eaters may behave well most of the time during meals and may eat 1 or 2 foods on their plate and ignore the others. They may touch or otherwise play with their food, but in general they are not afraid of it; they simply may not be prepared to put it in their mouths. Fussy or problematic eaters may behave poorly at the table. They may become very upset at the sight of any new foods on their plate. Fussy eaters may cry, throw their plate, or refuse to come to the table if the food reaches the table before they do. They may refuse to eat their favorite foods if they are on the same plate as unfamiliar foods. Some children may begin to gag the moment they see or smell food.15,40 Children become more accepting of new food if they are around adults that enjoy eating a wide variety of foods, including unfamiliar foods.

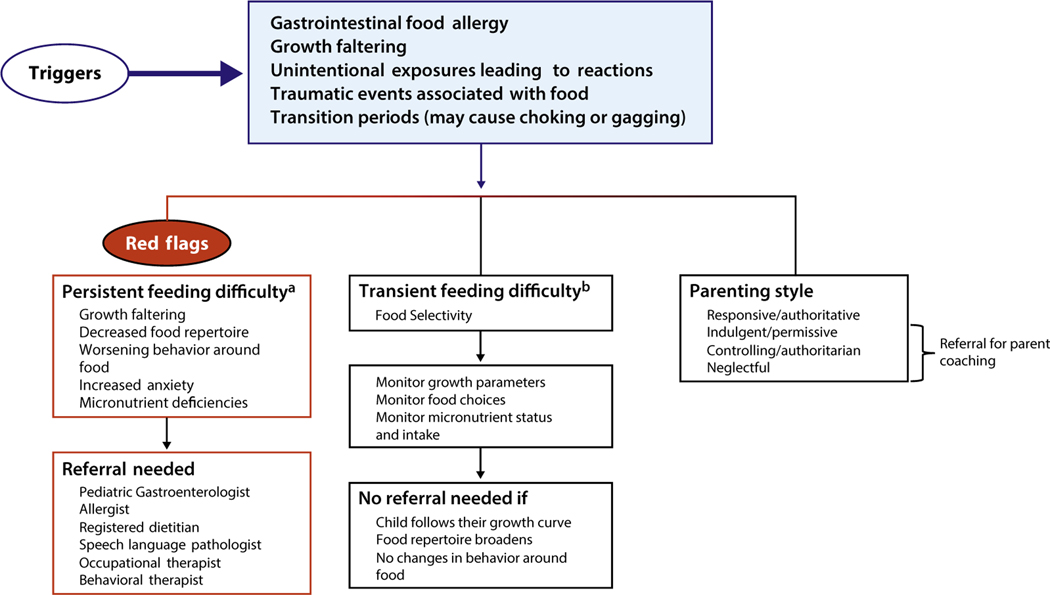

Children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders are at particular risk for developing feeding difficulties because of their negative experiences with food. Determining when a practitioner should refer a family for further assessment of a feeding difficulty presents a challenge. As described above, feeding a healthy child can be a challenge during different developmental stages as children learn how to express their own opinions and set their own boundaries around what foods they put into their mouths. Children often have periods when they would prefer to eat only a limited number of foods, which is sometimes referred to as a food jag. Feeding difficulties may also be transient. Signs and symptoms36 that may indicate that a child is experiencing something other than a typical or transient feeding issue include the following:

Falling off of the growth curve (further evaluation needed to ensure that growth was properly assessed)

List of preferred foods becomes shorter and shorter

Child begins to exhibit fear or anxiety around new foods

A child who was once well behaved at the table now may cry or even refuse to come to the table

A child becomes very rigid in the way in which food needs to be prepared or insists on only eating the same brand of food

Figure 1 outlines these factors and provides a guide for the practitioner on when to refer for feeding difficulties.

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm to guide practitioners on when to refer for feeding difficulties.

aPersistent feeding difficulty is defined as a feeding issue in which the child becomes more selective or restricted, growth may become compromised, and there are high levels of stress around eating in the home.

bTransient feeding difficulty is defined as a change in the child’s eating pattern that lasts a short period and therefore does not threaten nutritional status and the child is able to bring himself/herself along to a wider eating pattern with proper support from parents.

Management of Feeding Difficulties

Feeding difficulties cannot be viewed as just the child’s problem. Successful management requires that the health care team views this as a relational disorder between the child and the parent or caregiver.40 Addressing the child’s concerns with food and eating must be done in the context of the family unit and may require the parent or caregiver to get significant coaching in how to feed the child.36 The parent or caregiver may also need counseling to help them address any underlying anxiety that may be preventing them from offering a wider variety of safe foods.

Four different types of caregiver feeding styles have been described36,40: responsive or authoritative, neglectful, controlling or authoritarian, and indulgent or permissive. The responsive or authoritative feeder follows a division of responsibility in which the feeder decides what, where, and when food is offered and lets the child determine if and how much they are going to eat. The neglectful feeder may fail to offer food at regular times and to set limits as to what food is offered and when, and may offer developmentally inappropriate foods. They may not sit with their child during meal or snack times and if they do, may not make eye contact or engage in conversation. The controlling or authoritarian feeder often decides how much food the child should eat, ignores the child’s own hunger and satiety cues, and may use rewards or punishment to get the child to eat. The indulgent feeder completely caters to the child and may provide very little structure with meal and snack times. They will offer whatever food the child demands and may make separate food for each child at the table.36,40

The parent/caregiver plays a critical role in helping a child overcome feeding difficulties. Determining the parent/caregiver’s feeding style will help the health care team in offering the resources and training needed that will allow the parent/caregiver to help the child make progress. The health care team also needs to emphasize to parents/caregivers that eating is a skill that children learn at their own pace and they must be supported at their pace and not pressured to eat larger quantities or a greater variety of flavors or textures.

In addition to the feeding style, parental/caregiver anxiety about feeding the child should also be assessed. Negative experiences with food may not only be traumatic for children but also the adults who witness the event. Children may be ready to expand their food choices long before the parent feels comfortable doing so. Studies report that parents of food allergic children have increased levels of anxiety and poorer quality of life; therefore, parental anxiety rather than the organic disease present in the child may at times drive the feeding difficulty.41

Therapy Strategies and Methods of Managing Children With Non–IgE-Mediated Food Allergic GI Disorders

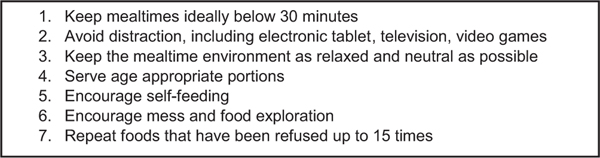

Although several methods have been described for managing feeding difficulties, limited data have been published on strategies specifically for children with non–IgE-mediated GI food allergies. Health care professionals working in this area have, however, implemented many interventions in their patient cohort, with perceived positive results that should be evaluated in future studies. These methods are described in further details below, and their uses in specific feeding difficulties are summarized in Table 2. A number of overarching strategies can be used in any child with non–IgE-mediated GI food allergy (Fig. 2) and can be combined with any of the methods below.

Figure 2.

General management strategy for management of feeding difficulties.

Division of Responsibility Approach

Satter’s Division of Responsibility (sDOR) is an effective management strategy that can help address the parent/caregiver feeding style as well as the child’s eating style.40 sDOR states that the parent/caregiver’s job is to determine when food is served, what food is served, and where it is served. The child’s job is to determine if he/she will eat the food that is being served and how much. As long as the parent/caregiver does his/her job with feeding and allows the child to do his/her job with eating, the child will eat the amount of food that is right for them.

The parent/caregiver who follows sDOR does not use pressure language (offering bribes or threatening punishment) and does not come to the table with an agenda to get the child to eat. The adult offers an organized, pleasant meal or snack time experience with flavors and textures that are developmentally appropriate for the child he/she is feeding. This parent/caregiver is considerate by offering foods that the child likes but does not cater to the child’s every demand for food. These parents/caregivers also understand that children may eat quite a lot at one meal and not very much at the next. They are also comfortable knowing that if the child does not prefer the foods served during the meal, the child will have an opportunity to eat at the next snack time.

The core of sDOR is trust. Eating and feeding is successful when there is mutual trust and respect around the table. The parent/caregiver must trust the child’s instincts on what food is safe and that the child will eat the amount of food that is right for them. The child must be able to trust that safe foods are going to be offered on a regular basis and that they will be allowed to explore new foods in a way that makes them feel comfortable and safe.40

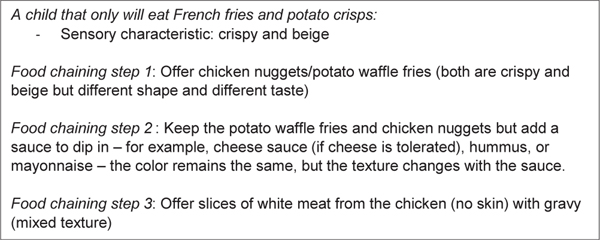

Food Chaining Approach

The food chaining method is a systematic approach for the treatment of children with selective food intake. This approach was first described by Fraker and Walbert42 in 2003 and uses an individualized, nonthreatening, home-based feeding program that allows for the expansion of foods, using new foods with similar sensory characteristics to accepted foods, including texture, color, and temperature. An example is provided in Figure 3. This method was subsequently studied in a small cohort of 10 children with extremely limited food intake; all children managed to expand their diet significantly after 3 months.43

Figure 3.

Example of the food chaining approach in managing a child with feeding difficulties.

There is paucity of data using this technique in children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders, although it is commonly used in practice. Further studies are needed to establish its effectiveness.

Sequential Oral Sensory Approach

The sequential oral sensory approach has several overlapping features with the food chaining approach in addressing sensory feeding problems. However, there are some significant differences. The original program developed by Toomey and Ross44 suggests a 12-week program that is based on 4 tenets: myths about eating, systematic desensitization, normal development of feeding and food choices, and how these are linked together. This biopsychosocial therapy method uses a multidisciplinary approach that integrates posture (not addressed in food chaining), sensory, motor, behavioral (not addressed in food chaining), and medical and nutritional factors in therapy sessions that are not home based (unlike food chaining). Limited data exist on its efficacy, which has been its main criticism. However, a small number of studies exist in patients with autism, neurologic impairment, and cerebral palsy.45,46 These studies have found that overall the SOS approach had a positive effect on feeding, particularly in children with neurologic impairment, but in some diagnoses (ie, autism) results were variable and the method needed adjusting.45,46 This method has also been implemented in children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic disorders, but to date results are anecdotal. Further prospective studies are therefore required in this population.

Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach in Management

Many studies have been published in regard to the positive effect of a multidisciplinary approach in children with feeding difficulties (Table 3).47,48 In children with non–IgE-mediated Gl food allergic disorders, the origin of feeding is likely to be multifactorial, and feeding difficulties can often be complex, requiring the input of a variety of health care professionals. McCormish et al49 described the ideal multidisciplinary approach for feeding difficulties as including medical, oral-motor, and behavioral input. In the context of EoE, EGIDs, FPIES, FPIP, and food protein–induced allergic dysmotility disorders, this implies the involvement of an allergist or gastroenterologist, a dietitian (nutrition), a speech and language therapist specializing in oral-motor skills, and a psychologist. However, depending on the target population and the type of feeding difficulties, multidisciplinary team members may vary, including an occupational therapist, developmental specialist, and nurses specializing in nutrition therapy. The cost and feasibility of having a joint feeding session need to be considered. Involving just the necessary health care professionals required for the particular feeding difficulty may improve logistics and reduce cost. The length of the intervention should be individualized for the need of each child, depending on how significant the feeding difficulties are at the initial presentation and how capable the family is at implementing the recommendations on their own.

Table 3.

Multidisciplinary Team Members That May Be Involved in the Management of Feeding Difficulties in Non–IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Allergies

| Specialist | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Physician (allergist, gastroenterologist) | Optimizes medical management |

| Facilitates the decision for enteral feeding support | |

| Facilitates the decision for further medical investigations | |

| Dietitian | Provides specialized nutrition tailored to each child’s abilities, likes, and limitations |

| Provides dietary elimination advice | |

| Optimizes nutrient intake within limited food variety | |

| Speech and language therapist | Assesses oral motor skills and provides exercises and techniques to improve |

| Offers advice on feeding bottles and utensils | |

| Psychologist | Provides advice on child’s feeding behavior and coping strategies for families |

| Occupational therapist | Assesses development and sensory desensitization (ie, messy food play and activities to improve acceptance of food based on their sensory characteristics) |

Conclusion

Feeding difficulties appear to be prevalent in children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders. They are observed to persist long after adequate management of the food allergic disorder by the practitioner. Early recognition and specialist referral are keys to successful management of feeding difficulties in children to potentially avoid nutritional deficiencies and faltering growth. Given the paucity of data on feeding difficulties in non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders, more research studies are needed to help determine the extent to which severity of symptoms, extent of dietary restrictions, and parental perception of the specific food allergic GI disease contribute to the development of this condition. Addressing feeding difficulties through a multidisciplinary approach will ensure that we create a healthy and thriving pediatric population despite their GI allergies.

Key Messages.

Non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders can disrupt a child’s feeding skill acquisition, resulting in feeding difficulties.

Symptoms related to non–IgE-mediated food allergic GI disorders can affect the relationship children have with food.

Overly restricted dietary elimination diets in early childhood can limit exposure and increase feeding difficulties.

Feeding difficulties can result in nutritional deficiencies and faltering growth. Therefore, timely recognition and referral for management are of paramount importance.

Several management approaches to feeding difficulty exist, dictated by the type of feeding difficulty present.

Successful management of a child with feeding difficulty is best achieved using a multidisciplinary approach, with addressing the child’s feeding and the caregiver feeding style being equally important.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Dr Chehade received research funding from the National Institutes of Health (U54 AI117804), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology and Nutricia; clinical trial funding from Regeneron, Shire, and Allakos; consulting fees from Shire, Allakos, and Adare; and lecture fees from Danone and the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences at Eisenhower and serves (no fees) on the medical advisory board for APFED, Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease, and the International Food Protein–Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Association. Dr Meyer received lecture fees from Mead Johnson, Danone and Nestle. Ms Beauregard received consulting fees from Nutricia North America and Nestle Health Sciences and serves on the medical advisory board for the Food Protein–Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Foundation.

References

- 1.Leung DYM, Sampson HA, Geha R, Szefler SJ. Pediatric Allergy: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:516–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiocchi A, Brozek J, Schunemann H, et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines. World Allergy Organ J. 2010;3:57–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221e229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampson HA, Anderson JA. Summary and recommendations: Classification of gastrointestinal manifestations due to immunologic reactions to foods in infants and young children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(suppl): S87–S94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chehade M, Jones SM, Pesek RD, et al. Phenotypic characterization of eosinophilic esophagitis in a large multicenter patient population from the consortium for food allergy research. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6: 1534–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Chehade M, Groetch ME, et al. International consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: executive summary-Workgroup Report of the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1111–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odze RD, Wershil BK, Leichtner AM, Antonioli DA. Allergic colitis in infants. J Pediatr. 1995;126:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandenplas Y, Koletzko S, Isolauri E, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92: 902–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer R, Fleming C, Dominguez-Ortega G, et al. Manifestations of food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies presenting to a single tertiary paediatric gastroenterology unit. World Allergy Organ J. 2013;6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lozinsky AC, Meyer R, De Koker C, et al. Time to symptom improvement using elimination diets in non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chehade M. IgE and non-IgE-mediated food allergy: treatment in 2007. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linscheid TR. Behavioral treatments for pediatric feeding disorders. Behav Modif. 2006;30:6–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg P, Williams JA, Satyavrat V. A pilot study to assess the utility and perceived effectiveness of a tool for diagnosing feeding difficulties in children. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2015;14:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burklow KA, Phelps AN, Schultz JR, McConnell K, Rudolph C. Classifying complex pediatric feeding disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27: 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukkada VA, Haas A, Maune NC, et al. Feeding dysfunction in children with eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e672–e677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borowitz KC, Borowitz SM. Feeding problems in infants and children: assessment and etiology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carruth BR, Ziegler PJ, Gordon A, Hendricks K. Developmental milestones and self-feeding behaviors in infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(1 suppl 1):s51–s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulthard H, Harris G, Emmett P. Delayed introduction of lumpy foods to children during the complementary feeding period affects child’s food acceptance and feeding at 7 years of age. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(suppl 1):S25–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan SA, Birch LL. Infant dietary experience and acceptance of solid foods. Pediatrics. 1994;93:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Developmental changes in the acceptance of protein hydrolysate formula. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1996;17:386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mennella JA, Forestell CA, Morgan LK, Beauchamp GK. Early milk feeding influences taste acceptance and liking during infancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90: 780S–788S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maslin K, Grimshaw K, Oliver E, et al. Taste preference, food neophobia and nutritional intake in children consuming a cows’ milk exclusion diet: a prospective study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:786–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carruth BR, Skinner JD. Feeding behaviors and other motor development in healthy children (2–24 months). J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy Y, Levy A, Zangen T, et al. Diagnostic clues for identification of nonorganic vs organic causes of food refusal and poor feeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer R, De Koker C, Dziubak R, et al. The impact of the elimination diet on growth and nutrient intake in children with food protein induced gastrointestinal allergies. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Drewett RF. How does maternal and child feeding behavior relate to weight gain and failure to thrive? data from a prospective birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1262–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer R, Rommel N, Van Oudenhove L, Fleming C, Dziubak R, Shah N. Feeding difficulties in children with food protein-induced gastrointestinal allergies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1764–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rommel N, De Meyer AM, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta P, Furuta GT, Brennan T, et al. Nutritional state and feeding behaviors of children with eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas AM, Maune NC. Clinical presentation of feeding dysfunction in children with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2009;29:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zangen T, Ciarla C, Zangen S, et al. Gastrointestinal motility and sensory abnormalities may contribute to food refusal in medically fragile toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staiano A. Food refusal in toddlers with chronic diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heine RG. Allergic gastrointestinal motility disorders in infancy and early childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerzner B, Milano K, MacLean WC Jr, Berall G, Stuart S, Chatoor I. A practical approach to classifying and managing feeding difficulties. Pediatrics. 2015;135: 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris G. Development of taste and food preferences in children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JC. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: a review. Appetite. 2008;50:181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birch L, Savage JS, Ventura A. Influences on the development of children’s eating behaviours: from infancy to adolescence. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2007;68: s1–s56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satter E. Child of Mine: Feeding With Love and Good Sense. Rev ed. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer R, Godwin H, Dziubak R, et al. The impact on quality of life on families of children on an elimination diet for Non-immunoglobulin E mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraker C, Boshart CA, Walbert L. Evaluation and Treatment of Pediatric Feeding Disorders: From NICU to Childhood. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fishbein M, Cox S, Swenny C, Mogren C, Walbert L, Fraker C. Food chaining: a systematic approach for the treatment of children with feeding aversion. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toomey KA, Ross ES. SOS approach to feeding. Perspect Swallowing Swallowing Disord (Dysphagia). 2011;20:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benson JD, Parke CS, Gannon C. A retrospective analysis of the sequential oral sensory feeding approach in children with feeding difficulties. J Occup Ther Schools Early Interv. 2013;6:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson KM, Piazza CC, Volkert VM. A comparison of a modified sequential oral sensory approach to an applied behavior-analytic approach in the treatment of food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Behav Anal. 2016;49:485–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall AP, Wake E, Weisbrodt L, Dhaliwal R, Spencer A, Heyland DK. A multifaceted, family-centred nutrition intervention to optimise nutrition intake of critically ill patients: the OPTICS feasibility study. Aust Crit Care. 2016;29: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marshall J, Hill RJ, Ware RS, Ziviani J, Dodrill P. Multidisciplinary intervention for childhood feeding difficulties. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60: 680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McComish C, Brackett K, Kelly M, Hall C, Wallace S, Powell V. Interdisciplinary feeding team: a medical, motor, behavioral approach to complex pediatric feeding problems. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2016;41:230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]