Abstract

Background

As the rates of vaccination decline in children with logistical barriers to vaccination, new strategies to increase vaccination are needed. The goal of this study was to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of the Vaccines For Babies (VFB) intervention, an automated reminder system with online resources to address logistical barriers to vaccination in caregivers of children enrolled in an integrated healthcare system. Effectiveness was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with parents of children less than two years old to identify logistical barriers to vaccination that were used to develop the VFB intervention. VFB included automated reminders to schedule the 6- and 12-month vaccine visit linking caregivers to resources to address logistic barriers, sent to the preferred mode of outreach (text, email, and/or phone). Parents of children between 3 and 10 months of age with indicators of logistical barriers to vaccination were randomized to receive VFB or usual well child care (UC). The primary outcome was percentage of days undervaccinated at 2 years of life. A difference in differences analysis was conducted.

Results

Qualitative interviews with 6 parents of children less than 2 years of age identified transportation, scheduling challenges, and knowledge of vaccine timing as logistical barriers to vaccination. We enrolled 250 participants in the trial, 45% were loss to follow-up. There were no significant differences in vaccination uptake between those enrolled in UC or the VFB intervention (0.51%, p=0.86). In Medicaid enrolled participants, there was a modest decrease in percentage of days undervaccinated in the VFB intervention compared to UC (6.3%, p=0.07).

Conclusion

Automated Reminders and with links to heath system resources was not shown to increase infant vaccination uptake demonstrating additional resources are needed to address the needs of caregivers experiencing logistical barriers to vaccination.

Keywords: Logistical Barriers, automated reminders, randomized controlled trial, qualitative interviews

1. Background

Vaccinations have been identified as one of the top ten greatest public health achievements, preventing more than 20 million cases of disease and saving $14 million in direct costs.[1, 2] However, there are persistent disparities in vaccination coverage for children living below poverty and those uninsured or Medicaid insured.[3-5] This disparity was highlighted with a decline in vaccination rates in uninsured and Medicaid-insured children in 2017.[5] The inequity in vaccination coverage is not solely based on financial barriers. Both uninsured and Medicaid-insured children are eligible for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program providing free childhood vaccination.[6] Logistical barriers, including scheduling challenges, knowledge of vaccine timing, childcare, and transportation, also limit access to care.[7] Thus, even in insured populations, logistical barriers to vaccination prevent utilization of recommended services.[8]

Healthcare systems often have resources available to address logistical barriers to care, including Medicaid’s Non-Emergency Medical Transportation program and after-hours care. The growing number of families with access to smart phones,[9] increases opportunities for phone and email outreach to link this hard-to-reach population to the available logistical barrier resources. Additionally, automated reminders have been shown to increase vaccine receipt and completion across multiple studies, reducing the knowledge gap in vaccine timing.[10-12] However, the mobility of the low-income population still make them particularly difficult to reach.[13] Contact information is not always consistent or available, as reflected in the low exposure rates found in studies assessing automated reminders in low-income populations.[14, 15] Allowing patients to choose the mode and contact information for outreach presents an opportunity for patients to identify the most consistent form of communication, minimizing the mobility barriers. This was demonstrated in a study showing an increase in HPV series completion in participants given a preference in the mode of reminder outreach.[16] Using automated reminders of vaccine visit timing, with links to resources designed to address logistical barriers to vaccination, delivered to participants using their preferred mode of contact, presents an opportunity to connect with this hard-to-reach population and address this growing disparity in childhood vaccination rates.

To address logistical barriers to vaccination, we developed Vaccines for Babies (VFB). VFB is a multi-pronged intervention using an automated outreach system with information to overcome logistical barriers to vaccination. The automated outreach is sent to participants preferred contact information. For this report we describe the development of VFB and effectiveness evaluation using a pragmatic randomized controlled trial assessing difference in childhood vaccination uptake between participants randomized to the VFB intervention and usual well child care (UC). We hypothesize, there will be a greater reduction in days undervaccinated in children in the VFB arm compared to UC.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Overview

Between October and December of 2014, we conducted qualitative interviews with caregivers to identify logistical barriers to obtaining vaccines for their child. The identified logistical barriers to vaccination were used to develop the VFB intervention. The intervention included an online resource and automated reminders to schedule the 6- and 12-month vaccine visits. Additionally, the VFB intervention provided an opportunity for participants to select the reminder mode (text, email, and/or phone) and contact information to be used in reminder outreach. To assess the impact of the VFB intervention on uptake of childhood vaccination, between June 2018 and March 2019 we conducted a pragmatic randomized controlled trial with caregivers of children 3 to 10 months of age experiencing logistical barriers to vaccination. Participants were randomized to receive the VFB intervention or usual well child care (UC) and followed through the child’s second year of life.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted with participants enrolled in an integrated healthcare system, Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO). KPCO servers approximately 600,000 patients, including 140,000 children. Hispanic ethnicity was reported in 15% of the KPCO population. Reported race was 61% white, 4% Black, and 11% other non-white. All study procedures were approved by the Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institutional Review Board

2.3. Qualitative Interviews and VFB Intervention Development

2.3.1. Participant identification and recruitment

We identified caregivers with children between 12 months and 2 years of age with logistical barriers to vaccination using the electronic health record (EHR). Children of caregivers were required to be enrolled in the KPCO health plan, were not fully vaccinated on time (undervaccination) with clinical indicators of logistical barriers to vaccination (no diagnosis code for vaccine refusal and less than 3 well child visits in the first year of life), and English speaking. At the time of recruitment for the qualitative interviews, a concurrent study assessing a vaccine hesitancy intervention trial was being conducted in the population of children less than 2 years of age enrolled in the healthcare system. Thus, we excluded participants currently enrolled in the trial. All eligible participants were recruited..[17]

Identified participants were recruited using mail, email and phone outreach. Eligibility was further evaluated during recruitment where an initial screening was conducted to determine the reason for the child’s undervaccination. Vaccines administered to the child and the timing of vaccines were reviewed with the caregiver. Caregivers reporting full vaccination on time, vaccine hesitancy, or health concerns impacting vaccination timing were excluded. After confirming that the caregiver experienced logistical barriers to vaccination, a phone interview was conducted with the participant.

2.3.2. Identification of Logistical Barriers to Inform the Intervention

Semi-structured interviews were audio recorded and conducted by a trained research staff (BB). After consent, participants were asked to describe the logistical barriers to vaccination for their child. Two research staff (NW, BB) reviewed audio recordings separately and identified logistical barrier to vaccination themes. In cases with discrepancy in themes identified, interviews were reviewed and discussed until a consensus was reached.

2.4. Development of the VFB intervention

The VFB intervention included automated reminders to schedule vaccine visits and access to an online resource. The online resource included health system resources available to address logistical barriers to vaccination and vaccination information. Findings from the qualitative interviews were used to inform the content made available in the online resource. Resources available within the healthcare system to address logistic barriers to vaccination included after hours care, walk in visits for vaccination, a dedicated staff member working with patients experiencing economic and housing barriers, and transportation resources. The vaccine information was derived from the content developed for a tailored vaccine website intervention for parents. Details of the intervention development are published elsewhere.[18]

The automated reminder system sent out reminders, based on participant preference, to schedule the 6 month and 12-month vaccine visits. Up to four reminders occurred to schedule each visit, two prior to the recommended visit due date and two following the recommended visit due date if it was not attended. Prior reminders occurred at 3 weeks and 1 week before, and past due reminders occurred at 2 and 4 weeks after the recommended visit due date. Reminders were not sent if the participant had already scheduled a visit with the primary care team within 2 months of the vaccine due date or had a recently administered vaccine (based on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) vaccine administration recommendations[19]). See table 1 for the reminder timing and exclusion criteria. With each reminder, participants were given an opportunity to opt-out of receiving reminders.

Table 1:

Vaccines For Babies Intervention Automated Reminder Timing and Exclusion Criteria

| Reminder | Reminder timing (child’s age) |

Vaccine exclusion* | Visit Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mth Pre due date 1 | 5 mths + 1 week (159-166 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 28 days (days 131-159) | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 8 months*** |

| 6 mth Pre due date 2 | 5 mths + 3 weeks (173-180 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 28 days (days 145-173) | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 8 months*** |

| 6 mth Post due date 1 | 6 mths + 2 weeks (196-203 days) | a vaccine administered** after first 6 month outreach (day 159-166) until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 8 months*** |

| 6 mth Post due date 2 | 6 mths + 4 weeks (210-217 days) | a vaccine administered** after first 6 month outreach (day 159-166) until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 8 months*** |

| 12 mth Pre due date 1 | 11 mths + 1 week (342-349 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 52 days (290 days)until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 14 months*** |

| 12 mth Pre due date 2 | 11 months + 3 weeks (356-363 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 52 days (304 days) until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 14 months*** |

| 12 mth Post due date 1 | 12 months + 2 weeks (379-386 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 52 days (day 327) until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 14 months*** |

| 12 mth Post due date 2 | 12 months + 4 weeks (393-400 days) | a vaccine administered** within the last 52 days (day 341) until current outreach date | a visit scheduled in Primary Care from day of current outreach to 14 months*** |

Vaccine exclusions timing was based on ACIP recommendations for vaccine administration

Vaccines administered include Hep B, DTaP, Hib, Pneumococcal, Polio, Rotavirus, MMR, Varicella, Combination vaccines: DTaP-HepB-Polio, DTaP-Hib-Polio, Hib-HepB, DTaP-Hib, MMR-Var.

Primary Care included pediatrics, internal medicine and family practice. Telephone visits were excluded

2.5. VFP Trial

We designed the VFB trial to assess effectiveness in a pragmatic, or real world, application of the intervention.[20] The intervention was information based and similar to other procedures provided as standard of care, posing minimal risk to participants. Thus, we were able to use passive consent, in which participants were automatically enrolled and had to actively opt-out to be removed from the study. Passive consent allowed us to enroll and randomize the entire cohort of eligible participants at patient identification. While this increased the size and representativeness of the study population, it also led to misclassification, particularly in newly enrolled participants. For example, patient information is often updated after the patient begins using the healthcare system or they may have been enrolled to address an emergency need that is not indicative of health system membership. In many cases a child may be unvaccinated due to parental vaccine hesitancy. As a new patient, the EHR reflects no vaccination, utilization or diagnosis of vaccine hesitancy. The EHR data will not accurately reflect the reason for vaccination delay until the child is seen in the clinic and the provider is able to capture the vaccine hesitancy. Thus, we re-evaluated eligibility at the end of the trial prior to analysis limiting the analyzed population to those meeting eligibility criteria.

2.5.1. Initial Participant identification

Caregivers experiencing logistic barriers to vaccination were identified using data derived from the EHR. We identified caregivers of children between ages 3 and 10 months who were behind on immunizations and did not have indicators of vaccine refusal including diagnosis code for vaccine refusal or receipt of recommended well child visits.[21, 22] Children were identified as behind on immunizations if they had greater than 20% days undervaccinated, and were enrolled in KPCO on the day of identification. Percent days undervaccinated (PDU) is a continuous measure evaluating the difference between the time when a vaccine dose should have been administered according to ACIP recommendations and when it was administered.[23, 24] The measure incorporates a month to allow for scheduling variability before days undervaccinated begins accruing. In the case of vaccines due at the 2-month visit, days undervaccinated begins to accrue at age 93 days (3 mths). PDU was calculated using the total number of days undervaccinated divided by the maximum number of days a child could be undervaccinated, excluding influenza vaccine. As the intervention was only developed in English, non-English speakers were excluded. Lastly, participants currently enrolled in an intervention trial evaluating a tailored online intervention designed to address vaccine hesitancy, were excluded to prevent contamination.[17]

2.5.2. Randomization

Randomization by the study statistician occurred at the time of participant identification. Identified caregivers were randomly assigned to the VFB intervention and usual care (UC) arms with a 1:1 allocation following simple randomization procedure using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary NC). Due to the nature of the study, participants were not blinded to the study arm assignment. The study investigator and statistician were blinded to study arm assignment until interpretation of the findings.

2.5.3. Obtaining Preference

Participants were identified in three waves. Participants in the VFB arm were contacted by the study team to elicit preference in the mode and contact information for reminder outreach (text, email, and/or phone). Participants received up to 5 contacts to obtain outreach preference including phone calls from the study team and a survey sent through mail, email, and text message. The survey included 2 items asking participants how they wanted to receive reminders (text, email, and/or phone) and the associated contact information. Survey data was collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at KPCO.[25] Outreach continued for four weeks. At the end of four weeks, participants who did not provide a preference were assigned to text message reminders using the primary phone number available in the EHR. If no working contact information was available in the EHR at the time of outreach, the automated system automatically sent reminders to the study team phone line to track missed exposure events.

2.5.4. VFB Intervention

The VFB intervention included usual care plus automated reminders to schedule the 6- and 12-month vaccine visit sent using the preferred outreach mode and contact information. Included in each vaccine visit reminder was a website link to the online resource with vaccine information and health system resources available to address logistical barriers to vaccination. The website required the caregiver to login with the child’s last name and date of birth. This login step allowed capture of website usage.

To address changes in contact information, participants could update preference and contact information with the study team at any time. Contact information for participants not providing a preference was updated at each reminder with the latest contact information available within the EHR. Standard health system protocol included updating contact information with most health system interactions.

2.5.5. Usual Care

Usual care participants received the standard of care at KPCO that was received by all patients, including those randomized to VFB. Standard of care at KPCO included automated reminders for a visit that was already scheduled (not a reminder to schedule a visit as was done in the VFB intervention). These automated appointment reminders were sent 3 days and 24 hours prior to the scheduled visit. Reminders were sent by text message or phone call. First, a text message was attempted. If the phone was not text enabled, a phone call was sent. Patients signed up on the online patient portal also received these reminders for scheduled visits by email. Reminders to schedule upcoming well child visits were provided as part of usual care in multiple ways (such as scheduling the first follow-up visit at hospital discharge after birth, receiving reminders from providers and after visit summaries at well child visits, and scheduling the upcoming well child visit at the current visits). However, there was no formal system reminding patients not using the system when they were due for the next vaccine visit.

2.5.6. Outcome

Our primary outcome was the difference in percentage of days undervaccinated (PDU) between baseline and follow-up, by study group. PDU was captured at baseline (randomization) as part of the inclusion criteria and again at follow when the child was 2 years of age or at disenrollment from the study. The following 8 vaccines were included in PDU calculations as appropriate for each timepoint; Hep B (hepatitis B), DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis), IPV (inactivated polio), PC (pneumococcal conjugate), Hib (haemophilus influenzae type B), rota (rotavirus), MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella), and varicella. Each vaccine receives a unique number of days that are combined for the total number of eligible days. As described in patient identification, days undervaccinated begins to accrue 30 days following the recommended vaccination visit date. As an example of calculating PDU, an infant did not receive any of the recommended two-month vaccines until halfway into month three. The total days undervaccinated would be 15 days for each vaccine, a total of 90 days. At four months, the total number of eligible days would be 30 per vaccine, a total of 180 days. In this case, the PDU at four months is 50%. If all vaccines are received on time moving forward, the number of eligible days will increase, but the number of days undervaccinated will remain stable, decreasing the PDU. In this case, at five months the total days unvaccinated remains 90 but the total number of maximum possible days undervaccinated is 360. The five-month percentage of days undervaccinated would be 25%.

We captured vaccination data through two sources. First, we used vaccine administration captured in the EHR. However, a population experiencing logistical barriers may also use health services available at other, more convenient, locations (e.g. public health services). To address this concern, the EHR vaccination data was supplemented with vaccination records on enrolled participants from the Colorado Information Immunization System (CIIS).[26] CIIS is a registry of vaccinations used by health systems and public health agencies across Colorado to track vaccination in patients. For systems utilizing the registry, including KPCO, it provides a confidential way to access member vaccine information for a more comprehensive assessment of vaccination history. CIIS was found to have 90% penetration compared to census data in the Denver community.[27] Immunization records were extracted from CIIS at participant identification, weekly for all upcoming patient reminders, and at study outcome assessment. Due to the penetration of CIIS and comprehensiveness of the EHR, missing vaccination data was interpreted as not receiving vaccines.

2.5.7. Exposure (subgroup analysis)

We identified exposure to the intervention at the end of follow-up using data captured from the automated reminder system and an online website tracking tool. A participant was considered exposed to the intervention if a text message or email was successfully sent, or a phone call connected. A phone call connection included contact with a person or voicemail system. Phone calls sent to the study team phone line (no available working contact information) were coded as unexposed events. The frequency of visits and pages visited on the intervention website were tracked using the online website tracking tool recording the participant, date, time, and webpage(s) viewed.

2.5.8. Post-randomization eligibility exclusions

We conducted a modified intention to treat analysis by keeping study arm assignment but excluding participants whom did not meet eligibility criteria. Participants were excluded from analysis if they were identified as ineligible including the caregiver was found to be vaccine hesitant, the child was fully vaccinated on time at the start of the trial, the caregiver was a non-English speaker, or there were data errors (such as incorrect date of birth). As vaccination data was not available on participant who were loss to follow-up, participants who had no insurance coverage, had no contact information, or opted out of the study were also excluded from analysis.

2.5.9. Analysis

We conducted a difference-in-difference analysis. Our primary analysis compared the estimated difference of PDU from baseline to follow-up (up to 2 years of age) between the VFB and UC arms. We used repeated measures linear regression model approach. This method accounts for the correlation in the outcome measures within subjects. We conducted two subgroup analyses. In our first subgroup analysis, we restricted the analyzed population to those with Medicaid insurance coverage on the date of randomization to assess the impact of the intervention on the growing undervaccinated Medicaid population.[5] As the target population could be difficult to reach[13] we sought to explore the impact of exposure to the intervention on vaccination outcomes. In the second subgroup analysis, we conducted a difference-in-differences comparison of PDU between participants exposed and unexposed to the intervention.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Interviews

We electronically identified 56 participants meeting eligibility criteria. After chart review, 33 participants were excluded due to parent vaccine refusal (n=6), recurring illness (n=5), full on time vaccination (n=19), data entry errors (n=1), and no KPCO insurance coverage (n=2). In the 23 eligible participants recruited, we were unable to contact 7, 5 did not have valid contact information, 2 reported no longer having insurance coverage, 2 were non-English speaking, and 1 did not attend the interview and we were not able to contact. We conducted 6 (26%) interviews with caregivers. Participants were all female, had some college (50% bachelor’s degree, 50% some college or associate’s degree), had a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds (50% white, 33% Hispanic, 17% mixed race), and had at least 2 children (83% 2 children, 17% 4 children) ranging in age from 1 to 13 years. Interviews identified the following themes for logistical barriers to vaccination: transportation, childcare, caregiver schedule challenges, knowledge of vaccine visit timing, parent health concerns preventing access to care, and negative health system experiences. Barriers included transportation, scheduling, childcare, and knowledge of vaccine visit timing. Barriers were reported by more than one participant indicating common themes were identified. Table 2 lists the barriers reported by participants and how the barrier was addressed in the VFB intervention.

Tables 2:

Logistical Barrier Themes Emerging from Qualitative Interviews, Frequency Reported, and How the Logistical Barrier was Addressed in the VFB Intervention

| Logistical Barrier Theme |

Frequency Reported N=7 |

VFB intervention source addressing logistic barrier theme. |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation | 2 |

|

| Schedule (work hours) | 5 |

|

| Child Care | 2 | Not included as no current resources available to address this need |

| Knowledge of Vaccine Timing | 5 |

|

We built the VFB online resource based on the barriers identified by participants and the resources available within the healthcare system (see landing page screenshot in figure 1). The VFB online resource incorporated an interactive map with health system locations and hours of operation, information on the recommended vaccine schedule (including information on the vaccines recommended at each time point and diseases they prevent), vaccine visit information (including ways to prepare, what to expect during and after the visit, and when to call the doctor), links to transportation resources, and contact information for the health system community specialist linking families to community resources (such as housing, food, and transportation).

Figure 1:

Vaccines For Babies (VFB) Online Resource Landing Page

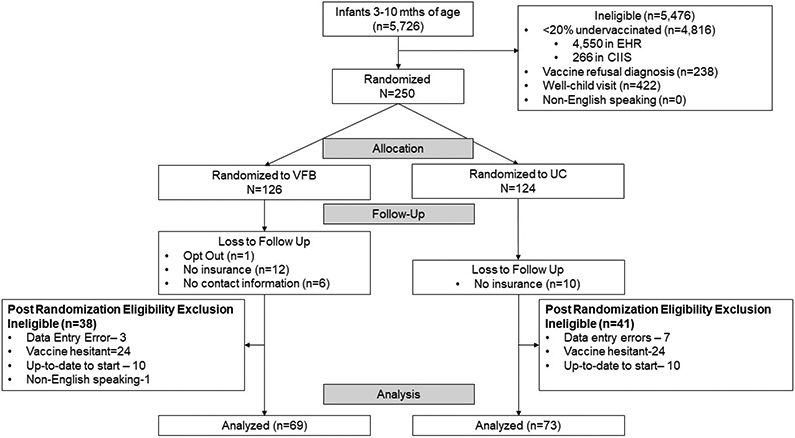

3.2. VFB Intervention Trial

There were 250 participants identified and randomized for the trial (VFB=126, UC=124). In the VFB arm, 25 (20%) provided a preference (19 text, 4 email, 1 email and text, 1 email and phone). A total of 107 (43%) participants were excluded from analysis due to vaccine refusal, no insurance coverage, full vaccination at randomization, non-English speaking, data entry errors, and no available contact information (see figure 2). On average, enrolled children were 7 months of age, were slightly more likely to be female (56%), and had unknown race and ethnicity (45%). Approximately half of the population had Medicaid insurance coverage. Patient characteristics (see table 3) were not statistically different between the UC and VFB arms.

Figure 2:

Vaccine For Babies (VFB) Randomized Controlled Trial CONSORT Flow Diagram

Table 3:

Characteristics of the VFB Intervention Trial Study Population

| Characteristic | Intervention arm (n=69) |

Usual care arm (n=73) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, months, mean (SD) | 7.38 (62.17) | 6.89 (62.97) |

| Age at the end of follow-up, months, mean (SD) | 19.89 (192.0) | 20.65 (162.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (56.52) | 41 (56.16) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 18 (26.09) | 20 (27.40) |

| Others | 9 (13.04) | 11 (15.07) |

| Unknown | 42 (60.87) | 42 (57.73) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 13 (18.84) | 14 (19.18) |

| Non-Hispanic | 23 (33.33) | 26 (35.62) |

| Unknown | 33 (47.83) | 33 (45.21) |

| Insurance at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Medicaid | 31 (44.93) | 40 (54.79) |

| Commercial | 32 (46.38) | 32 (43.84) |

| Others | 6 (8.70) | 1 (1.37) |

None of the variables were statistically different between the study arms at alpha of 0.05

There were 47 (68%) VFB participants exposed to the automated reminders. Of those exposed, 9 (19%) viewed the online resource. Each participant only viewed the online resource on one occasion. The vaccine schedule (n=6) and vaccine visit information (n=4) pages were the most frequently visited.

The primary assessment of the reduction in PDU based on difference in differences revealed no significant differences between study arms (0.51%; p=0.86), see table 4. Secondary assessment restricting to the Medicaid population was not statistically different (6.3%; p=0.07), see table 5. The exposure comparison analysis did not significantly differ in those exposed versus unexposed to the intervention based on the differences in differences analysis (3.9%; p=0.21), see table 6.

Table 4:

Percentage of Days Undervaccinated (PDU) in the VFB and UC arms at Baseline and Follow-up (n=142)

| PDU | VFB arm (n=69) |

Usual care arm (n=73) |

|---|---|---|

| PDU at baseline, mean (SD) | 56.60 (28.20) | 58.05 (27.50) |

| PDU at end of follow-up, mean (SD) | 50.42 (32.58) | 52.39 (29.53) |

Difference in difference between the two study arms of 0.51% at a p-value of 0.86

Table 5:

Percentage of Days Undervaccinated in the VFB and UC arms in Patients with MEDICAID Insurance at Baseline and Follow-up (n=71)

| PDU | Intervention arm (n=31) |

Usual care arm (n=40) |

|---|---|---|

| PDU at baseline, mean (SD) | 62.08 (24.31) | 57.68 (27.74) |

| PDU at end of follow-up, mean (SD) | 54.92 (32.41) | 56.84 (27.39) |

Difference in difference between the two study arms of 6.3% at a p-value of 0.07

Table 6:

Percentage of Days Undervaccinated in Participants Exposed to the VFB Intervention and Unexposed to the VFB Intervention at Baseline and Follow-up (n=142)

| PDU | Exposed to intervention (n=47) |

Not exposed to intervention (n=95) |

|---|---|---|

| PDU at baseline, mean (SD) | 50.56 (26.64) | 60.70 (27.81) |

| PDU at end of follow-up, mean (SD) | 42.02 (29.21) | 56.09 (30.88) |

Difference in difference between the two study arms of 3.9% at a p-value of 0.21

4. Discussion

An automated outreach intervention linking patients to resources for addressing logistical barriers to vaccination did not impact uptake of infant immunization. We found that the difference in PDU from baseline to follow-up did not differ between the VFB and UC arms. Although not statistically significant, Medicaid children in the VFB arm had fewer days undervaccinated than children in the UC arm. This outcome indicates subpopulations of patients experiencing logistical barriers to vaccination may benefit from components of the VFB intervention.

While multiple reviews have found reminders/recall are an effective strategy to increase vaccination, the results are often modest.[10, 11] Additionally, the online tool providing information on resources to overcome logistical barriers was only viewed by 19% of the population. Thus, an automated system with links to resources available to overcome barriers to care may not be sufficient to address logistical barriers to vaccination. Intervention strategies may require additional resources and outreach. Hambidge et al, designed an intervention to address low vaccination rates in a safety net health systems in Denver, Colorado.[28] The intervention used a multiple step approach starting with automated reminders for infant vaccination followed by a nurse visits for noncompliant patients. The vaccination rates were significantly higher in the intervention group compared to usual care. The significant results of this trial indicate a more resource intensive approach may be needed to address logistical barriers to vaccination.

The results of our study also highlight barriers to deliver interventions to this hard-to-reach population in a timely fashion. The lack of health system utilization makes it difficult to obtain current, accurate information on patients both in terms of health status and contact information. This was shown with the large number of patients excluded from the study (43%) and unexposed to the intervention (32%). Our sample exposed to the outreach was similar to an automated reminder outreach intervention conducted in public health clinics in Georgia where 37% of the intervention population was not exposed to the reminder outreach.[15] This indicates the addition of choice in how information is sent is not sufficient to reach this population. Additional strategies to identify and engage this hard-to-reach population, such as community partnerships [29] or phone outreach, are needed to encourage use of the resources available within a healthcare system.

There are many strengths to this study. We evaluated the VFB intervention using a rigorous randomized pragmatic design, which increases the external validity of the results.[30] Specifically, enrollment of participants at different ages and vaccination statuses reflects a real-world application of the intervention, thus providing results reflective of what would be expected with implementation in an integrated healthcare system. Additionally, vaccination outcomes were extracted from both the EHR and CIIS systems. This provides more accurate capture of vaccine administration than recall[31] and offers an opportunity to identify vaccines administered outside the healthcare system.[26]

This study is limited in serval ways. The trial was assessed in a single integrated healthcare system in Colorado and may not be reflective of patients with other types of health coverage or no health coverage. Similarly, participants were not screened on logistical barriers to vaccination at enrollment. While EHR indicators of logistical barriers to vaccination were used as inclusion criteria, restricting the patient population to those with confirmed barriers to vaccination may have yielded different outcomes. However, using this approach would limit the ability to enroll through passive consent, restricting the population size and representativeness. The available cohort with logistical barriers to vaccination within the integrated health system was small (n=133). A larger sample of patients experiencing logistical barriers may have yielded different results. Additionally, the low number of website views (19%) also warrants further exploration of opportunities to improve VFB. Lastly, Spanish speakers were excluded from the study. However, in this cohort of patients 0% of the population had the need for a translator indicated in the EHR, suggesting other cohorts may better represent the non-English speaking population. To fully assess the impact of VFB, further evaluation of this intervention in systems serving a larger population of patients experiencing logistical barriers, Spanish speaking cohorts, targeting important subgroups including MEDICAID patients, and in populations with no health coverage is needed.

5. Conclusion

While automated reminders have been shown to increase vaccination, this RCT indicates it may not be enough to address the needs of caregivers experiencing logistical barriers to vaccination. As the number of children undervaccinated continues to grow,[5, 32] further development of strategies to address the needs of this hard-to-reach population are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge, Bre Barella, PhD, for her support on this article. Dr. Barella conducted and analyzed the qualitative interviews for this study.

Funding Source

This work was supported the National Institutes of Child Health and Development [grant # 1R01HD079457]

Abbreviations

- VFB

Vaccines for Babies, the intervention evaluated in the trial

- UC

Usual well child care provided to children under two years of age.

- KPCO

Kaiser Permanente Colorado

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- PDU

Percentage of Days Undervaccinated

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Amanda Dempsey serves on advisory boards for Merck, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur. These companies played no role in this research.

All authors attest they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Clinical Trials Registration #: NCT03516682

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Ten great public health achievements--United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:619–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, Messonnier M, Wang LY, Lopez A, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133:577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kolasa M. National, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19-35 Months - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Dietz V. Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19-35 Months - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1065–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kang Y. Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19-35 Months - United States, 2017. Mmwr-Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67:1123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Mieczkowski TA, Mainzer HM, Jewell IK, Raymund M. The vaccines for children program. Policies, satisfaction, and vaccine delivery. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wolf ER, O'Neil J, Pecsok J, Etz RS, Opel DJ, Wasserman R, et al. Caregiver and Clinician Perspectives on Missed Well-Child Visits. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:30–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yawn BP, Xia Z, Edmonson L, Jacobson RM, Jacobsen SJ. Barriers to immunization in a relatively affluent community. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13:325–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Smith A Record share of Americans now own smartphones, have home broadband. Pew Research Center. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vann JCJ, Jacobson RM, Coyne-Beasley T, Asafu-Adjei JK, Szilagyi PG. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Szilagyi PG, Bordley C, Vann JC, Chelminski A, Kraus RM, Margolis PA, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates: A review. JAMA. 2000;284:1820–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Favin M, Steinglass R, Fields R, Banerjee K, Sawhney M. Why children are not vaccinated: a review of the grey literature. International health. 2012;4:229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Anderson M, Kumar M. Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption. Pew Research Center. 2019;March 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1702–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stehr-Green PA, Dini EF, Lindegren ML, Patriarca PA. Evaluation of telephoned computer-generated reminders to improve immunization coverage at inner-city clinics. Public health reports. 1993; 108:426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kempe A, O'Leary ST, Shoup JA, Stokley S, Lockhart S, Furniss A, et al. Parental Choice of Recall Method for HPV Vaccination: A Pragmatic Trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Glanz JM, Wagner NM, Narwaney KJ, Kraus CR, Shoup JA, Xu S, et al. Web-based Social Media Intervention to Increase Vaccine Acceptance: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dempsey AF, Kwan BM, Wagner N, Pyrzanowski J, Brewer SE, Sevick C, et al. Development of a Values-Tailored Web-Based Intervention for New Mothers to Increase Infant Vaccine Uptake. Journal of Medical Internet Research. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, Kroger A, Pellegrini C. General best practice guidelines for immunization: best practices guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 2015;350:h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Glanz JM, Newcomer SR, Narwaney KJ, Hambidge SJ, Daley MF, Wagner NM, et al. A population-based cohort study of undervaccination in 8 managed care organizations across the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:274–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Freed GL, Clark SJ, Pathman DE, Schectman R. Influences on the receipt of well-child visits in the first two years of life. Pediatrics. 1999;103:864–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Zhao C, Catz S, et al. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29:6598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The Relationship Between Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines Survey Scores and Future Child Immunization Status A Validation Study. Jama Pediatrics. 2013;167:1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Groom H, Hopkins DP, Pabst LJ, Murphy Morgan J, Patel M, Calonge N, et al. Immunization information systems to increase vaccination rates: a community guide systematic review. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21:227–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Maravi ME, Snyder LE, McEwen LD, DeYoung K, Davidson AJ. Using spatial analysis to inform community immunization strategies. Biomedical informatics insights. 2017;9:1178222617700626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hambidge SJ, Phibbs SL, Chandramouli V, Fairclough D, Steiner JF. A stepped intervention increases well-child care and immunization rates in a disadvantaged population. Pediatrics. 2009;124:455–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Patsopoulos NA. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Daley MF, Glanz JM, Newcomer SR, Jackson ML, Groom HC, Lugg MM, et al. Assessing misclassification of vaccination status: Implications for studies of the safety of the childhood immunization schedule. Vaccine. 2017;35:1873–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, Kharbanda EO, Daley MF, Galloway L, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.