Abstract

Introduction

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs) are rare diseases characterised by non-suppurative inflammation of skeletal muscles and muscle weakness. Additionally, IIM is associated with a reduced quality of life. Strength training is known to promote muscle hypertrophy and increase muscle strength and physical performance in healthy young and old adults. In contrast, only a few studies have examined the effects of high intensity strength training in patients with IIM and none using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) set-up. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of high-intensity strength training in patients affected by the IIM subsets polymyositis (PM), dermatomyositis (DM) and immune-mediated necrotising myopathy (IMNM) using an RCT study design.

Methods and analysis

60 patients with PM, DM or IMNM will be included and randomised into (1) high-intensity strength training or (2) Care-as-Usual. The intervention period is 16 weeks comprising two whole-body strength exercise sessions per week. The primary outcome parameter will be the changes from pre training to post training in the Physical Component Summary measure in the Short Form-36 health questionnaire. Secondary outcome measures will include maximal lower limb muscle strength, skeletal muscle mass, functional capacity, disease status (International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group core set measures) and questionnaires assessing physical activity levels and cardiovascular comorbidities. Furthermore, blood samples and muscle biopsies will be collected for subsequent analyses.

Ethics and dissemination

The study complies with the Helsinki Declaration II and is approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2020–553). The study is approved by The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-20030409). The findings of this trial will be submitted to relevant peer-reviewed journals. Abstracts will be submitted to international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: rheumatology, sports medicine, rehabilitation medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the most robust methodology to assess the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

The study will represent the first large-scale (n=60) RCT to examine the effects of high intensity strength training in patients with polymyositis, dermatomyositis and immune-mediated necrotising myopathy.

The findings of the RCT, whether positive or negative, will contribute to future recommendations for the implementation of adjunct treatment strategies in patients with myositis.

The findings of the RCT might not be generally applicable for all subgroups of patients with myositis, especially patients with sporadic inclusion body myositis.

The long-term impacts of prolonged high-intensity strength training on quality of life cannot be elucidated from the current study.

Introduction

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs), collectively termed myositis, is a heterogeneous group of rare diseases that share features as non-suppurative inflammation of skeletal muscles and muscle weakness.1 2 The main subsets of IIMs consists of polymyositis (PM), dermatomyositis (DM), sporadic inclusions body myositis (sIBM) and immune-mediated necrotising myopathy (IMNM).3–7

Patients with myositis generally respond well to prednisolone and other anti-inflammatory drugs,8 9 with sIBM as an exception.10–12 Even though anti-inflammatory drugs in general reduce disease activity in IIM, patients typically do not fully regain their pre-disease muscle function.13 14 In addition, patients with IIM have reduced quality of life. Patients with a disease duration of roughly 7 years scored ~50% lower within the physical domain of the Short Form 36 (quality of life) questionnaire compared with healthy age-matched adults.15 16 In a recent OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology) survey on patient-reported outcome measures, patients with myositis listed ‘muscle symptoms’, ‘fatigue’ and ‘levels of physical activity’ as key challenging aspects of daily living.17 Therefore, it is paramount to address these aspects and improve physical function to increase quality of life for patients with myositis.

The effect of physical exercise has been investigated in patients with PM and DM in a few smaller non-randomised studies18–22 and in general, physical exercise was shown to be a safe and effective therapeutic tool to improve physical function and activities of daily living.18–22

Two randomised controlled trials (RCT) concerning endurance training have been conducted in patients with PM and DM (n=14 and n=15, respectively).23 24 Six weeks of bicycle exercises and step aerobics improved physical fitness and muscle strength in patients with PM and DM23 and aerobic exercise in combination with resistive endurance training led to improvements in general health, exercise performance and aerobic capacity, respectively, in patients with PM, DM and IMNM.24–26 The effect of high intensity strength training has only been investigated in limited number of patients with myositis (excluding sIBM) with promising results in terms of increased muscle strength, reduced disease activity and reduced signs of physical impairment, along with no signs of increased inflammation within the trained muscles.27–29 However, none of these studies included assessments of quality of life and despite the promising results, a strict RCT study design is currently lacking.

Two training studies performed comprehensive immunohistochemistry analysis, with a focus on inflammation and none of the studies observed signs of increased inflammation following the training interventions.28 30 Nonetheless, the effect of high-intensity strength training at the myocellular level has never been investigated in patients with PM, DM and IMNM using an RCT study design.

The aims of the present study, therefore, are to use a RCT study design to investigate the effects of high-intensity strength training on (1) quality of life, (2) muscle strength, muscle mass, physical function and disease activity in patients with IIM compared with patients with control (IIM) receiving Care-as-Usual and (3) additionally, explorative outcomes as the underlying myocellular adaptations will be examined by repeated muscle biopsy sampling.

Methods and analysis

The current RCT is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and any changes to the protocol will be implemented here.

Study design

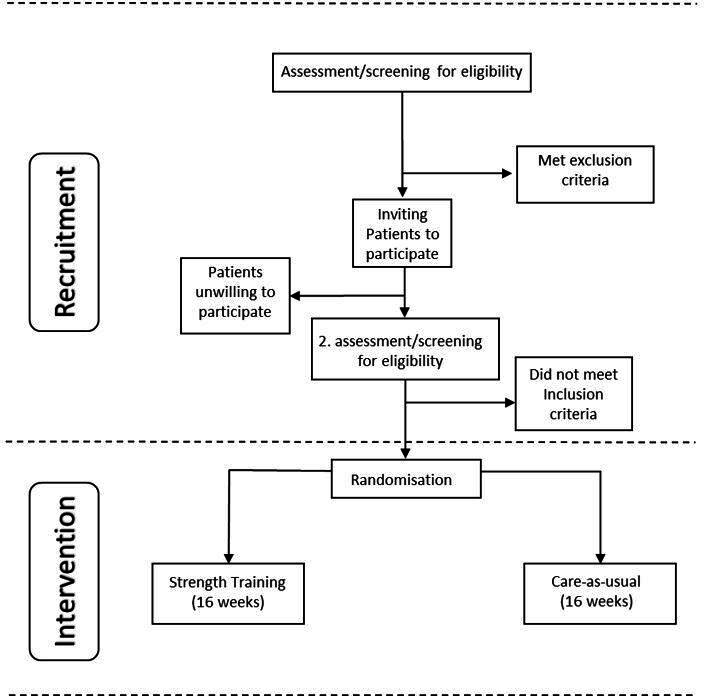

The study is a two-armed RCT. Sixty patients diagnosed with IIM (PM, DM and IMNM) will be included in a 16-week training intervention study (figure 1). Patients will be allocated randomly in the two subject groups in a 1:1 ratio, with stratification of IIM subgroups to ensure even distribution between intervention arms (training vs no training). The randomisation code will be generated by a biomedical laboratory technician with no further relation to the study, using an online tool (Research Randomizer, www.randomizer.org). The study has conformed to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines for constructing a clinical trial.31

Figure 1.

Study schematics. The intervention group will receive 16 weeks of high-intensity strength training. The control group will receive Care-as-Usual throughout the intervention period, defined as keeping physical activity levels the same as prior to participation in the study. Both groups will maintain the usual medical treatment related to the myositis disease throughout the intervention period.

Outside the scope of the RCT, we intend to perform a 1-year follow-up measurement, which would include the same outcome variables as pre-intervention and post-intervention, with the exception of muscle biopsies.

Blinding

The two physiotherapists who will be conducting the pre and post testing of physical function, maximal lower limb muscle power and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans will be blinded to participants’ group allocation. The physician assessing IIM-specific disease measures (disease damage and activity, etc), as well as the statistician performing all statistical analysis will also be group allocation blinded. The patients and the lead investigator in charge of the supervised training cannot be blinded for group allocation.

Patients

Only patients with an affiliation to Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, will be assessed for eligibility in the study. Eligible patients will be identified through the electronic patient record system at Rigshospitalet by an extraction on diagnosis codes (M33.1—‘Other dermatomyositis’, M33.2—’Polymyositis’, M33.9—’Dermatopolymyositis unspecified’ and G72.49—‘Other inflammatory and immune myopathies, not elsewhere classified’). The study intends to include stable patients with IIM only. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in table 1. Patients deemed eligible by the leading physician will receive invitation by letter or email.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Patients, age ≥18 years old, fulfilling the criteria for IIMs by EULAR/ACR.42 43 | Patients with sporadic inclusion body myositis and overlap myositis (myositis combined with another autoimmune rheumatic diseases), except Sjögren Syndrome. |

| Prednisolone ≤5 mg/day and stable dosage of immunosuppressive treatment for at least 1 month prior to inclusion in the study. | Comorbidity preventing resistance training (eg, severe heart/lung disease, uncontrolled hypertension (systolic >160 mm Hg and/or diastolic >100 mm Hg), severe knee/hip arthritis). |

| IIM diagnosis established at least 6 months prior to inclusion in the study. | Alcohol and/or drug abuse. Defined by the guidelines issued by The Danish Health Authority. |

EULAR/ACR, European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology; IIMs, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies.

Patient and public involvement

To strengthen the study in general and the strength training protocol, five patients with myositis were recruited for an advisory board to advise the research group in matters relevant for the patients and their role in the research study. The advisory board will persist through the entirety of the study and asked to give feedback on all matters relevant for the patients. Patients were chosen based on age, disease length, sex and general background to make sure the advisory board was as diverse as possible.

Intervention protocol

High-intensity strength training

The high-intensity (ie, heavy load) strength training protocol will consist of two exercise sessions per week and all training sessions will be supervised. The initial training loads will be estimated based on maximal test (five repetitions maximum (RM)) prior to the first training session. The first 2 weeks will be familiarisation period, where each exercise will be performed in three sets of 10 repetitions at an intensity of 15 RM. At week three each session will consist of three sets of each exercise using a training load corresponding to 10 RM to failure, which will be kept for the remaining part of the training intervention. The weight will be progressively adjusted across successive exercise sessions when participants are able to complete two extra repetitions (ie, 12 repetitions) in the last set of the respective exercise. The training protocol will be a whole-body training protocol and consist of five exercises using machines: horizontal bench press, horizontal leg press, seated rows, weighted knee extension and seated biceps curls.

The respective muscles will be working for approximately 45 s per set, with intermittent pauses of 90 s.27 28 Borg scale (6–20) will be used for assessing perceived exertion during and following the exercise sessions (aim following session: 16–18). All training loads for each training session will be recorded in an individual training diary for each patient (eg, exercise adherence, training load and adverse events).

Care-as-Usual

Care-as-Usual is defined as maintaining the level of physical activity at the same level as prior to initiation of the study. Furthermore, the usual medical treatment related to the myositis disease will be maintained throughout the timeline of the study for both groups.

Outcome variables

All study outcome measures are presented in table 2. All outcome measures will be measured at baseline and following the 16-week intervention period. Demographical information (age, gender, disease duration and time from first symptoms) will be drawn from clinical records from the electronic patient record system at Rigshospitalet.

Table 2.

Summary of outcome variables

| Instrument for data collection | |

| Primary outcome | |

| Quality of life—Physical Component Summary | SF-36 |

| Secondary outcomes | |

| Strength measures | |

| Leg power | Power rig |

| Handgrip strength | Handheld dynamometer |

| Functional capacity | |

| Muscle endurance | Functional Index 3 test |

| Combined function | 30 s chair rise test |

| Combined function | Timed up-and-go test |

| Gait function | 2-min walk test |

| Balance | SPPB—balance part |

| Body composition | |

| Whole-body, appendicular (arms and legs) and lower-limb lean mass | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| Fat-free mass, body fat and total mass | Bioimpedance |

| Disease activity | |

| Physician Global Activity | VAS score (1–10) |

| Patient Global Activity | VAS score (1–10) |

| Extra-muscular Disease Activity | VAS score (1–10) |

| Muscle strength | Manual muscle test 8 |

| Self-perceived physical functions | Health Assessment Questionnaire |

| Creatine kinase | Blood test analysis |

| Disease damage | |

| Physician global assessment of disease damage | VAS score (1–10) |

| Patient global assessment of disease damage | VAS score (1–10) |

| Questionnaires | |

| Basic cardiovascular questionnaire concerning medical conditions, current medication, heart symptoms and smoking habits | |

| Self-reported levels of physical activity | IPAQ-long |

| Quality of life—The Mental Health Component Summary | SF-36 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | |

| Body mass index | Height/weight measures |

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Sphygmomanometer |

| Lipid profile, HbA1c, troponins, NT-proBNP | Blood test analysis |

| ECG | ECG machine |

| Explorative outcomes | |

| Muscle biopsy analysis | Immunohistochemistry |

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IPAQ-long, International Physical Activity Questionnaire - long; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro b-type Natriuretic Peptide; SF-36, Short Form-36 health questionnaire; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome variable will be the change in the Physical Component Summary (PCS) measure from baseline to 16 weeks assessed by the Short Form-36 health questionnaire (SF-36), with scores ranging from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).32 The SF-36 is proposed by The International Myositis Outcome Assessment Collaborative Study Group (IMACS) as the preferred quality of life assessment tool.32

Secondary outcomes

Assessment of physical function and maximal muscle strength

Physical function will be tested using Functional Index 3,33 30 s chair rise,34 timed up-and-go35 and 2-min walk testing.36 Leg power will be measured by power rig.37 Handgrip strength will be measured38 and lastly a test for static balance with three feet positions (feet together, semi tandem and full tandem) will be performed.39

Body composition

Body composition as well as whole-body, appendicular (arms and legs) and lower-limb lean mass will be evaluated by DEXA. Bioimpedance measures will also be collected.

Disease activity and damage

Several outcome measures proposed by the IMACS to evaluate disease activity and disease damage in patients with IIM will be obtained.2 Patient and Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity and Extramuscular Global Assessment will be evaluated using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, 100 mm).2 The Manual Muscle Test 8 will be used to determine muscle strength in eight predefined muscles. Muscle strength is graded from 0 (zero; no contraction felt in the muscle) to 10 (normal; holds test position against strong pressure).2 Perceived physical function is reported by the patients, using the Health Assessment Questionnaire.2 Plasma creatine kinase (CK) will be measured by blood sampling.2 Patient and Physician Global Assessment of Disease Damage will be evaluated using a VAS (100 mm).2

Questionnaires

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire - long (IPAQ-long) concerning the level of self-reported physical activity and a questionnaire concerning medical conditions, current medication, heart symptoms, smoking habits and so on, will be filled out by all study participants. The Mental Health Component Summary measure from the SF-36 will also be recorded.

Cardiovascular co-morbidities

Traditional cardiovascular risk factor will be measures, including body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, plasma lipid profile (low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides and total cholesterol) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). In addition, troponins, N-terminal pro b-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) and ECG will be measured.

Explorative outcomes

Muscle biopsy

Biopsy samples will be acquired ad modum conchotome vastus lateralis (~100 mg).40 Immunohistochemistry will be used to analyse myofiber cross-sectional area, fibre type composition, B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes, macrophages, satellite cells and myonuclei.41

Statistical considerations

The calculation of the number of subjects is based on the PCS values from the SF-36 questionnaire in patients with PM and DM reported by Poulsen et al. Reported PCS values were 36.5 with a SD for 9.5.16 The current study is a superiority trial and intends to demonstrate a significant change with the training intervention protocol of at least 20% with a statistical significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80% while anticipating a dropout rate of 10%. Based on sample size calculations (www.sealedenvelope.com/power/continius-superiority) based on the above-mentioned values and dropout rate, a total of 60 patients was estimated to be recruited.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome variable is the change in PCS using the SF-36 questionnaire from baseline to post 16 weeks of intervention. The statistical analysis of the primary outcome will be conducted using an ‘intention-to-treat’ approach. For the primary outcome, an independent t-test will be conducted to determine the difference in change between the two groups. Likewise, independent t-tests will be conducted to determine all other outcomes measured throughout the study. In addition, a ‘per protocol’ approach also will be employed. The criteria for being included in the ‘per protocol’ analysis is having participated in at least two-third of all exercise sessions.

Ethical aspects and dissemination

Ethical considerations

The study will stay true to the Helsinki declaration II and is approved by The Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-20030409). Further, the study is approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2020–553) and all data accumulated will be handled confidentially and under secrecy in accordance with the guidelines and approval conditions of The Danish Data Protective Agency. Written and verbal informed consent will be collected from all patients prior to participation in the study, according to Danish law (see online supplemental file 1 for patient consent form). In publication, there will not be any information that could identify any of patients partaking in the project.

bmjopen-2020-043793supp001.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)

There is no commercial interest at stake within the project. Possible ‘conflict of interests’ will be uncovered before the start of the intervention.

Dissemination policy

The results of the current RCT will be published in peer-reviewed journals. Abstracts will be submitted for poster presentations at international conferences (eg, American College of Rheumatology). Authorship is granted to authors who provide essential contributions to the creation of the final publications. Both contributions via writing and/or assisting in conducting the clinical trial are accepted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Ingrid Lundberg (Karolinska Institute), Associate Professor Helene Alexanderson (Karolinska Institute), PhD Anders Jørgensen and the patient advisory board for their valuable input to the design of the current randomised controlled trial protocol. We used the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials checklist when writing this report.

Footnotes

Contributors: LPD is the principal investigator on the current trial. KYJ is the coordinator of the trial and has drafted the manuscript. PA, CS and HDS are co-coordinators of the trial and supply academical depth and experience. EB provided statistical expertise. JLN provided insight and expertise concerning clinical trials. All authors took part in the study design and assisted with the project funding. All authors have participated in the design of the trial and assisted with the draft of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Danish Rheumatism Association—grant number R185-A6606; The AP Moller Foundation—grant number 20-L-0031; Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet—grant number N/A.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Nuhr M, et al. Aerobic capacity in adult dermatomyositis/polymyositis patients and healthy controls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:1–5. 10.1016/S0003-9993(00)90212-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rider LG, Giannini EH, Harris-Love M, et al. Defining clinical improvement in adult and juvenile myositis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:603–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mammen AL. Necrotizing myopathies: beyond statins. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:679–83. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-Mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015;17:72. 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1734–47. 10.1056/NEJMra1402225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll MB, Newkirk MR, Sumner NS. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy: a unique subset of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Clin Rheumatol 2016;22:376–80. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selva-O'Callaghan A, Pinal-Fernandez I, Trallero-Araguás E, et al. Classification and management of adult inflammatory myopathies. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:816–28. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30254-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zong M, Lundberg IE. Pathogenesis, classification and treatment of inflammatory myopathies. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:297–306. 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon PA, Winer JB, Hoogendijk JE, et al. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2012:CD003643. 10.1002/14651858.CD003643.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Askanas V, Engel WK. Inclusion-body myositis: a myodegenerative conformational disorder associated with Abeta, protein misfolding, and proteasome inhibition. Neurology 2006;66:S39–48. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192128.13875.1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benveniste O, Guiguet M, Freebody J, et al. Long-term observational study of sporadic inclusion body myositis. Brain 2011;134:3176–84. 10.1093/brain/awr213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalakas MC. Pathogenesis and therapies of immune-mediated myopathies. Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:203–6. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalakas MC, Koffman B, Fujii M, et al. A controlled study of intravenous immunoglobulin combined with prednisone in the treatment of IBM. Neurology 2001;56:323–7. 10.1212/WNL.56.3.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson Mahowald M. The benefits and limitations of a physical training program in patients with inflammatory myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2001;3:317–24. 10.1007/s11926-001-0036-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regardt M, Welin Henriksson E, Alexanderson H, et al. Patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis have reduced grip force and health-related quality of life in comparison with reference values: an observational study. Rheumatology 2011;50:578–85. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen KB, Alexanderson H, Dalgård C, et al. Quality of life correlates with muscle strength in patients with dermato- or polymyositis. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2289–95. 10.1007/s10067-017-3706-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regardt M, Mecoli CA, Park JK, et al. OMERACT 2018 modified patient-reported outcome domain core set in the life impact area for adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Rheumatol 2019;46:1351–4. 10.3899/jrheum.181065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexanderson H, Stenström CH, Lundberg I. Safety of a home exercise programme in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a pilot study. Rheumatology 1999;38:608–11. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.7.608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexanderson H, Stenström CH, Jenner G, et al. The safety of a resistive home exercise program in patients with recent onset active polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Scand J Rheumatol 2000;29:295–301. 10.1080/030097400447679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varjú C, Pethö E, Kutas R, et al. The effect of physical exercise following acute disease exacerbation in patients with dermato/polymyositis. Clin Rehabil 2003;17:83–7. 10.1191/0269215503cr572oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escalante A, Miller L, Beardmore TD. Resistive exercise in the rehabilitation of polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 1993;20:1340–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertolucci F, Neri R, Dalise S, et al. Abnormal lactate levels in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: the benefits of a specific rehabilitative program. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2014;50:161–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Aringer M, et al. Improvement of physical fitness and muscle strength in polymyositis/dermatomyositis patients by a training programme. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:196–200. 10.1093/rheumatology/37.2.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Katz A, et al. Improved exercise performance and increased aerobic capacity after endurance training of patients with stable polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:R83. 10.1186/ar4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alemo Munters L, Dastmalchi M, Andgren V, et al. Improvement in health and possible reduction in disease activity using endurance exercise in patients with established polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with a 1-year open extension followup. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1959–68. 10.1002/acr.22068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexanderson H, Munters LA, Dastmalchi M, et al. Resistive home exercise in patients with recent-onset polymyositis and dermatomyositis -- a randomized controlled single-blinded study with a 2-year followup. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1124–32. 10.3899/jrheum.131145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexanderson H, Lundberg IE. Disease-specific quality indicators, outcome measures and guidelines in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007;25:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nader GA, Dastmalchi M, Alexanderson H, et al. A longitudinal, integrated, clinical, histological and mRNA profiling study of resistance exercise in myositis. Mol Med 2010;16:455–64. 10.2119/molmed.2010.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Souza JM, de Oliveira DS, Perin LA, et al. Feasibility, safety and efficacy of exercise training in immune-mediated necrotising myopathies: a quasi-experimental prospective study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:235–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munters LA, Loell I, Ossipova E, et al. Endurance exercise improves molecular pathways of aerobic metabolism in patients with myositis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1738–50. 10.1002/art.39624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller FW, Rider LG, Chung YL, et al. Proposed preliminary core set measures for disease outcome assessment in adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology 2001;40:1262–73. 10.1093/rheumatology/40.11.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernste FC, Chong C, Crowson CS, et al. Functional Index-3: a valid and reliable functional outcome assessment measure in patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis. J Rheumatol 2021;48:94–100. 10.3899/jrheum.191374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist 2013;53:255–67. 10.1093/geront/gns071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexanderson H, Broman L, Tollbäck A, et al. Functional index-2: validity and reliability of a disease-specific measure of impairment in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:114–22. 10.1002/art.21715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy R, Cooper R, Shah I, et al. Is chair rise performance a useful measure of leg power? Aging Clin Exp Res 2010;22:412–8. 10.1007/BF03324942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordenskiöld UM, Grimby G. Grip force in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia and in healthy subjects. A study with the Grippit instrument. Scand J Rheumatol 1993;22:14–19. 10.3109/03009749309095105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puthoff ML. Outcome measures in cardiopulmonary physical therapy: short physical performance battery. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2008;19:17–22. 10.1097/01823246-200819010-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorph C, Nennesmo I, Lundberg IE. Percutaneous conchotome muscle biopsy. A useful diagnostic and assessment tool. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1591–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen KY, Jacobsen M, Schrøder HD, et al. The immune system in sporadic inclusion body myositis patients is not compromised by blood-flow restricted exercise training. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:293. 10.1186/s13075-019-2036-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open 2017;3:e000507. 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundberg IE, Tjärnlund A, Bottai M, et al. 2017 European League against Rheumatism/American College of rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2271–82. 10.1002/art.40320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043793supp001.pdf (66.7KB, pdf)