Abstract

Introduction

Lipoedema is characterized as subcutaneous lipohypertrophy in association with soft-tissue pain affecting female patients. Recently, the disease has undergone a paradigm shift departing from historic reiterations of defining lipoedema in terms of classic edema paired with the notion of weight loss-resistant leg volume towards an evidence-based, patient-centered approach. Although lipoedema is strongly associated with obesity, the effect of bariatric surgery on thigh volume and weight loss has not been explored.

Material and Methods

In a retrospective cohort study, thigh volume and weight loss of 31 patients with lipoedema were analyzed before and 10–18 and ≥19 months after sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). Fourteen patients, with distal leg lymphoedema (i.e., with healthy thighs), who had undergone bariatric surgery served as controls. Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model adjusted for patient age and initial BMI.

Results

Adjusted initial thigh volume in patients with lipoedema was 23,785.4 mL (95% confidence interval [CI] 22,316.6–25,254.1). Thigh volumes decreased significantly in lipoedema and control patients (baseline vs. 1st follow-up, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0001; baseline vs. 2nd follow-up, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0013). Adjusted thigh volume reduction amounted to 33.4 and 37.0% in the lipoedema and control groups at the 1st follow-up, and 30.4 and 34.7% at the 2nd follow-up, respectively (lipoedema vs. control p > 0.999 for both). SG and RYGB led to an equal reduction in leg volume (operation type × time, p = 0.83). Volume reduction was equally effective in obese and superobese patients (weight category × time, p = 0.43).

Conclusion

SG and RYGB lead to a significant thigh volume reduction in patients with lipoedema.

Keywords: Lipoedema, Leg volume, Bariatric surgery, Gastric bypass, Sleeve gastrectomy

Introduction

Lipoedema is characterized as subcutaneous lipohypertrophy of the limbs in association with soft-tissue pain in the affected region [1, 2]. Although there are estimates of its incidence in patients referred to specialist clinics, the incidence in the general population remains largely unknown [3, 4]. To date, the diagnosis of lipoedema is based on clinical presentation only and cannot be generally verified by imaging, serologic or genetic testing, or clinical measurement [1, 5].

There is a strong association of lipoedema with obesity. In specialist clinics, almost 90% of patients with lipoedema are obese (BMI ≥30) [4, 6]. Fifty percent of patients with lipoedema present with a BMI ≥40, underlining the clinical relevance in the cohort of bariatric patients [6]. However, there seems to be a widespread bias that limb volume and lipoedema symptoms do not respond to weight loss [7, 8, 9]. Some even define lipoedema as a disease failing “to respond to extreme weight loss modalities” [7]. This concept has recently been challenged as it is contrary to others' clinical experience [10]. Nevertheless, there is no systematic study analyzing the effect of sustained weight loss on limb volume or symptoms in patients with lipoedema. Regarding bariatric surgery and lipoedema, there are a total of 4 documented cases [11, 12].

Hence, there is a considerable lack of data defining the effect of weight loss on lipoedema. We therefore retrospectively analyzed thigh volumes in a well-characterized cohort of patients with lipoedema following bariatric surgery.

Material and Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study comparing patients with lipoedema to controls with obesity (BMI ≥35) following bariatric surgery. As leg volumetry of fully healthy individuals with obesity was not available, the control group consisted of patients with obesity (BMI ≥35) and healthy thighs who participated in an interdisciplinary obesity program. This program is designed for patients with lipoedema or lymphoedema. The control group consisted of patients with distal leg lymphoedema only (i.e., with healthy thighs). The diagnostic criterion for lipoedema was painful, dysproportional fat distribution of the lower extremities. In accordance with the European Lipoedema Forum Consensus, edema was not considered a diagnostic criterion [2]. Diagnosis of lipoedema was confirmed independently by 2 specialists from an international referral center for lymphoedema and lipoedema (the senior author's institution). Initial leg volume was determined from April 2013 to December 2017. Two time-windows were retrospectively defined: 10–18 months and 19–45 months, with follow-up visits at 18 and 45 months, respectively.

Participants

All patients included in the interdisciplinary obesity program at the senior author's institution were screened. This program accepts patients with obesity (BMI ≥35) and lipoedema or lymphoedema. It includes inpatient medical, endocrinological, and psychological assessments as well as dietary counseling. All patients are assessed for eligibility for bariatric treatment. Consecutively, patients receive prescheduled outpatient appointments. Selection criteria were a diagnosis of lipoedema without proximal obesity-related lymphoedema (the lipoedema group), distal leg lymphoedema (the control group), scheduled bariatric surgery, and at least 1 postoperative follow-up visit including leg volumetry at the senior author's institution. A total of 45 patients (31 lipoedema and 14 distal leg lymphoedema) were identified. All data were entered into a custom-designed database.

Volume Measurement and Bariatric Operation

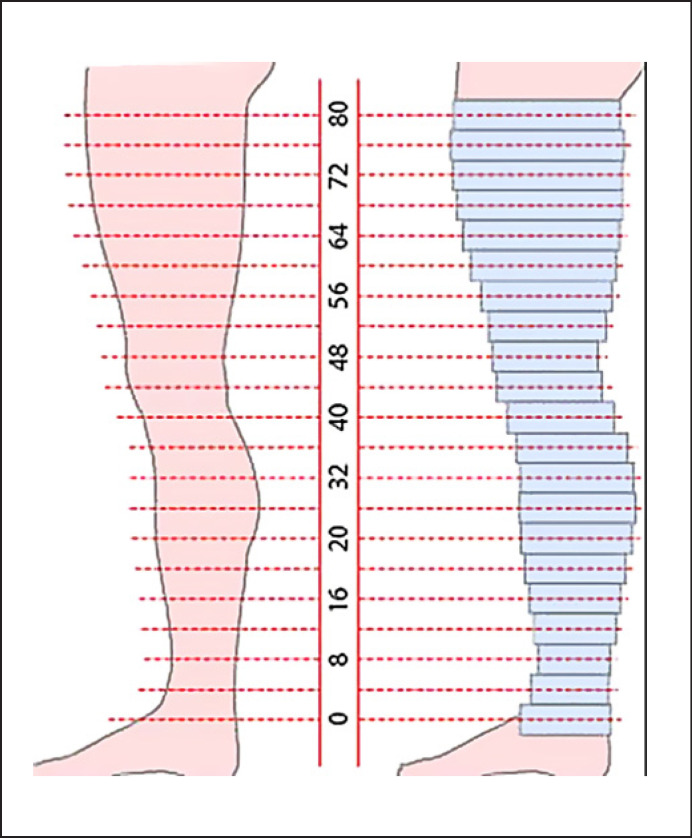

Volume measurement was conducted by dividing the leg into cylinders of 4-cm height. Leg circumferences were determined every 4 cm starting at the ankle. The last measurement was taken just below the inguinal ligament. Each measurement taken determines the circumference of a cylinder with 4-cm height as depicted in Figure 1. Leg volume is defined as the sum of all segmental cylinders. To determine thigh volume, only cylinder volumes above the knee of both thighs (left and right) were added.

Fig. 1.

Schematic image of leg volume measurement. Leg circumference is determined every 4 cm from the ankle to the inguinal ligament (left side). Each measured circumference determines a cylinder with a 4-cm height (right side). The sum of all cylinder volumes above the knee determines the thigh volume.

Bariatric operations were performed, according to German guidelines for bariatric and metabolic surgery, in 15 German bariatric centers from December 2013 to June 2018. Patients with lipoedema underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) (n = 20), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (n = 9), or one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB; n = 2). In the control group, 11 patients underwent SG, 2 underwent RYGB, and 1 underwent OAGB.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism v8 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and SPSS. Continuous variables were characterized using mean and confidence interval (CI) and categorial variables as n (%) in each category. A linear mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) approach was used to compare the 2 groups with respect to thigh volume and weight loss over time. This model included the patient as a random effect. Group allocation, follow-up visit, group allocation-by-visit interaction, age, and baseline BMI were interpreted as fixed effects. An unstructured within-patient covariance structure was assumed. For the analysis of thigh volume reduction, the excess BMI loss (EBMIL) at the 1st follow-up visit instead of the baseline BMI was interpreted as a fixed effect.

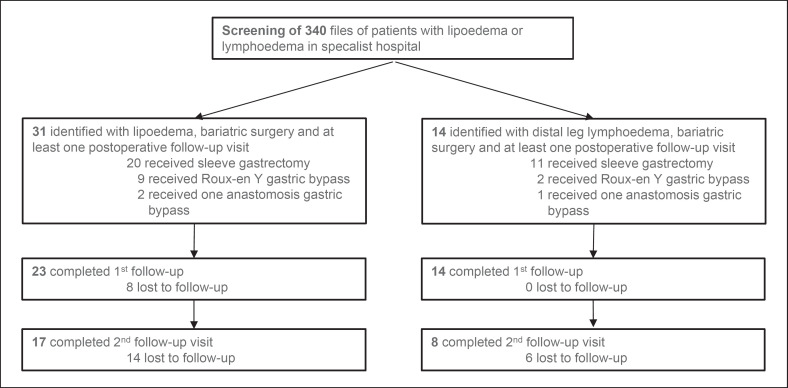

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare longitudinal baseline patient characteristics. Correlations were defined applying Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Absolute numbers and fractions of patients available for statistical evaluation are displayed in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of all patients throughout the study, including the type of surgery and numbers lost to follow-up.

Results

At baseline, mean BMI was 48.5 (45.5–51.4) in patients with lipoedema and 55.2 (51.9–58.5) in the control group (p = 0.004). Waist-to-height ratio was significantly lower in patients with lipoedema (p = 0.0015). Mean time from surgery to the 1st control visit was 14.0 (13.2–14.8) months. The 2nd visit was conducted a mean 26.4 (23.8–29.1) months after surgery. Complete patient characteristics are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Lipoedema group (n = 31) | Control group (n = 14) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 50.6 (47.4–53.7) | 55 (51.5–58.5) | 0.0494 |

| Weight, kg | 128.2 (119.5–137) | 148.6 (137.9–159.3) | 0.0044 |

| Female sex | 100% | 100% | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 48.5 (45.5–51.4) | 55.2 (51.9–58.5) | 0.0037 |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.0015 |

Values express mean (95% confidence interval), unless otherwise indicated.

Thigh Volume

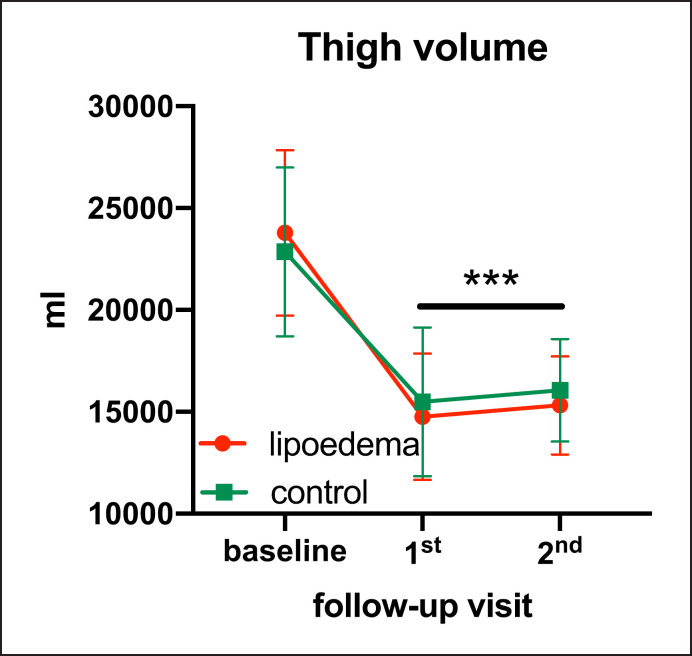

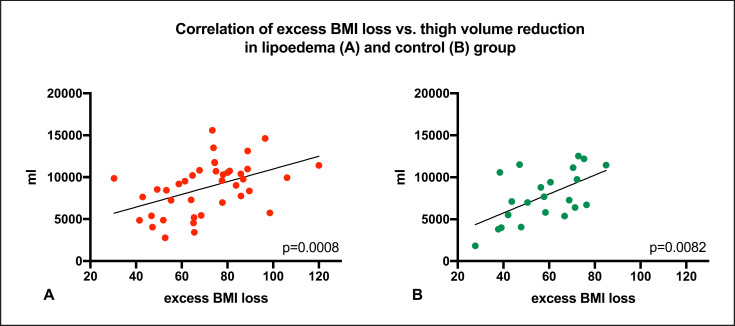

In patients with lipoedema, thigh volume correlated significantly with initial BMI (p < 0.0001) and EBMIL at the 1st follow-up (p < 0.0001). Compared to controls over complete follow-up, thigh volume in patients with lipoedema was not statistically different (group allocation × time, p = 0.227). Adjusted baseline thigh volume was 23,785,361 (22,316.6–25,254.1) mL in patients with lipoedema and 22,854,659 (20,625.0–25,084.4) mL in controls. Following bariatric surgery, thigh volume decreased significantly in both groups (Fig. 3). Thigh volumes and p values are displayed in Table 2. Adjusted thigh volume reduction amounted to 33.4% in lipoedema and 37.0% in controls at the 1st follow-up visit (7,935.2 [6,766.7–9,103.7] and 8,467.1 [6,063.3–9,781.5] mL, respectively; p > 0.999). Thigh volume reduction significantly correlated with EBMIL in both groups (p = 0.0008 and control p = 0.0082, respectively; Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative graph of adjusted mean thigh volume of patients with lipoedema and controls (error bars depict standard error). *** p < 0.0001, baseline vs. lipoedema for 1st and 2nd follow-up; baseline vs. control p = 0.0001 for 1st follow-up and p = 0.0013 for 2nd follow-up.

Table 2.

Adjusted thigh volume and statistical comparisons

| Baseline | 1st follow-up visit | p value3 | 2nd follow-up visit | p value3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh volume | |||||

| Lipoedema group (n = 31) | 23,785.4 (22,316.6–25,254.1) | 14,763.6a (13,461.9–16,065.4) | <0.0001 | 15,316.7c (14,139.6–16,493.8) | <0.0001 |

| Controls (n = 14) | 22,854.7 (20,625.0–25,084.4) | 15,493.9b (13,524.5–17,463.2) | 0.0001 | 16,055.7d (14,259.6–17,851.8) | 0.0013 |

| Thigh volume1 | |||||

| SG (n = 20) | 23,311.7 (21,624.5–24,998.8) | 14,285.9e (12,914.2–15,657.6) | <0.0001 | 14,935.5g (13,524.0–16,346.9) | <0.0001 |

| Gastric bypass2 (n = 11) | 23,473.9 (21,085.8–25,861.9) | 14,011.7f (12,019.4–16,004.0) | <0.0001 | 14,802.5h (12,736.3–16,868.7) | 0.0008 |

| Thigh volume1 | |||||

| Superobese (n = 11) | 26,606.0 (23,961.9–29,250.1) | 15,652.2f (13,530.7–17,773.7) | <0.0001 | 16,228.7f (14,022.8–18,434.6) | 0.0001 |

| Obese (n = 20) | 21,539.1 (19,597.5–23,480.7) | 13,273.5e (11,736.0–14,811.0) | <0.0001 | 14,062.1i (12,441.8–15,682.5) | <0.0001 |

Values express mean (95% confidence interval). a n = 23, b n = 14, c n = 17, d n = 8, e n = 16, f n = 7, g n = 12, h n = 5, i n = 10.

Volume assessment in patients with lipoedema only.

Two patients had an omega-loop bypass.

With Bonferroni correction.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot of thigh volume reduction and excess BMI loss in lipoedema (a) and control group (b). The p value refers to Spearman's rank correlation.

In patients with lipoedema, the type of bariatric surgery (LSG vs. RYGB) had no statistically different impact on thigh volume reduction (operation × time, p = 0.83). Patients with lipoedema and a BMI of ≥35 to <50 experienced a thigh volume reduction of 33.2% at the 1st follow-up; in those with a BMI ≥50, this reduction was 44.4%. Leg volume reduction was statistically similar between these subgroups (group × time, p = 0.43). As an example, Figure 5 shows the thighs of a patient with lipoedema before and after bariatric surgery.

Fig. 5.

A patient with lipoedema before (left side) and 14 months (right side) after sleeve gastrectomy.

Weight Loss

Adjusted EBMIL was 70.7% (64.1–77.3%) in patients with lipoedema and 59.2% (49.5–73.9%) in controls at the 1st follow-up visit, and 67.4% (37.5–60.8%) and 60.1% (50.1–69.9%) at the 2nd follow-up visit, respectively. Adjusted total weight loss (%TWL) amounted to 34.2% (30.9–37.5%) in patients with lipoedema and 28.8% (24.0–33.6%) in controls at the 1st follow-up visit, and 32.9% (29.7–36.2%) and 29.2% (24.3–34.1%) at the 2nd follow-up visit, respectively. Adjusted EBMIL and %TWL were not statistically different between groups at either follow-up visit (EBMIL: 1st follow-up, p = 0.10; 2nd follow-up, p = 0.44; %TWL: 1st follow-up, p = 0.13; 2nd follow-up, p = 0.42).

Discussion

This trial demonstrates a significant reduction in thigh volume in patients with lipoedema during weight loss after bariatric surgery. Adjusted thigh volume reduction was not different to controls. Neither type of bariatric surgery nor obesity category had a statistical impact on thigh volume reduction. Weight loss of patients with lipoedema was statistically similar to that of controls.

Thigh volume in patients with lipoedema is commonly believed to be weight loss-resistant [7, 13]. This trial demonstrates an adjusted 33.4% reduction of initial thigh volume following a SG or bypass surgery. These results therefore stand in sharp contrast to those in the published literature. Previous studies [7, 8, 13], almost exclusively, trace the weight resistance of leg volumes in patients with lipoedema back to the original publication by Wold et al. [14] in 1951, who analyzed 119 women with the aim of defining all elements of lipoedema. They reported that patients with lipoedema noticed no difference in leg volume following caloric restriction despite a decrease in subcutaneous adipose tissue of the upper body. This observation was relativized by the authors themselves; possibly, these patients experienced ineffectiveness of conservative weight loss therapy, rather than this being an intrinsic feature of lipoedema [15, 16]. To the best of our knowledge, our trial is the first to systematically analyze leg volume in lipoedema patients following sustained weight loss.

The lipoedema guidelines recommend liposuction as a possible surgical treatment [1, 5]. Indeed, studies show successful reduction in leg volume and a decrease in pain in the extremities after this procedure [17, 18]. However, a recent review directed at health care providers in Canada concluded that the “quality of evidence for the effectiveness of liposuction for lipoedema is limited” as it is based on a small number of retrospective studies [19]. In view of limited available data, Bertsch et al. [20] suggested a rigorous patient selection focused on lower BMI. A prospective randomized study on women with disproportional adipose tissue deposits demonstrated an accumulation of abdominal adipose tissue after thigh liposuction to an extent that outweighed the initial body fat loss in the thigh region [21]. Another study reported an average reduction in leg volume of 6.9% after liposuction in patients with lipoedema after 4–5 sessions [17]. Liposuction cannot be regarded as the first treatment option for patients with lipoedema and obesity (BMI ≥35). However, the effect size of a leg volume reduction of around 7% currently serves as benchmark of therapeutic effectiveness [2, 17]. In our study, the adjusted leg volume reduction in lipoedema patients following bariatric surgery was 33.7%.

Earlier data on poor lower-extremity volume reduction following weight loss may indicate impaired overall weight loss in patients with lipoedema [6]. Our study clearly demonstrates that weight loss in patients with lipoedema was not reduced compared to controls. Indeed, the mean EBMIL was 11.5% higher in patients with lipoedema. Although this difference is not statistically significant, it may be clinically relevant. In this respect, our results are consistent with all 4 reported cases of patients with lipoedema following bariatric surgery [11, 12]. In summary, the data on weight loss following bariatric surgery do not indicate inferiority of lipoedema patients to controls in this trial or in large cohorts of bariatric patients [22].

This study has several limitations. All patients with lipoedema and bariatric surgery within the abovementioned time window and with at least 1 follow-up visit were included, but there was a risk of selection bias due to the retrospective nature of the study. The diagnosis of lipoedema was based on clinical presentation only and therefore carried a risk of misdiagnosis. However, all patients referred with a lipoedema diagnosis were reevaluated at the senior author's institution.

Thigh volume is significantly associated with BMI. Initial BMI was significantly different in the lipoedema and control groups, which both consisted of patients with obesity-related lymphoedema. This disease typically occurs in patients with a BMI >40 and is aggravated along with increasing BMI [23]. The patients from the obesity program at the senior authors' institution had a comparatively high BMI, so although the model was adjusted to the initial BMI, this may have affected comparison of thigh volumes between the lipoedema and control groups.

We can also not fully exclude the possibility of low-level lymphoedema in the region in this group. The main limitation of this study is that it focused on thigh volume reduction but did not include other symptoms of patients with lipoedema. However, previous studies show that symptoms in patients with lipoedema improve following leg volume reduction [17, 24]. This is consistent with our experience.

Conclusion

Our finding of a massive reduction in leg volume following bariatric surgery stands in clear contrast to earlier assumptions [7, 8]. Indeed, bariatric surgery is an effective option to reduce leg volume in patients with obesity and lipoedema and ought to be investigated further.

Statement of Ethics

The complete study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Freiburg (298/18) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All patients received patient information and gave written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The trial was funded by the Foeldi Clinic, Hinterzarten, Germany and Department of General and Visceral Surgery, Center for Obesity and Metabolic Surgery, Medical Center, University of Freiburg, Germany (internal funding).

Author Contributions

J.M.F. and T.B.: study design, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. L.S. and G.E.: data acquisition and manuscript drafting. G.S.: drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. M.F. and G.M.: conception of the study and critical revision of the manuscript. The manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

References

- 1.Halk AB, Damstra RJ. First Dutch guidelines on lipedema using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Phlebology. 2017 Apr;32((3)):152–9. doi: 10.1177/0268355516639421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertsch T, Erbacher G, Corda D, Damstra RJ, van Duinen K, Elwell R, et al. Lipoedema − myths and facts, Part 5. Phlebologie. 2020;49((01)):31–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Földi M. F.l.E., Kubik S., Textbook of Lymphology. New York: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertsch T. E.G., Lipoedema − myths and facts Part 1. Phlebologie. 2018;47((02)):84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reich-Schupke S, Schmeller W, Brauer WJ, Cornely ME, Faerber G, Ludwig M, et al. S1 guidelines: lipoedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15((7)):758–67. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Child AH, Gordon KD, Sharpe P, Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, et al. Lipedema: an inherited condition. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Apr;152A((4)):970–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck DW, 2nd, Herbst KL. Lipedema: A Relatively Common Disease with Extremely Common Misconceptions. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016 Sep;4((9)):e1043. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012 Feb;33((2)):155–72. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmeller W, Meier-Vollrath I. Lipoedema - New Facts of a Fairly Unknown Disease. Akt Dermatol. 2007;33((07)):251–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertsch T, Erbacher G. Lipoedema − myths and facts Part 3. Phlebologie. 2018;47((04)):188–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bast JH, Ahmed L, Engdahl R. Lipedema in patients after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 Jun;12((5)):1131–2. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouwels S, Huisman S, Smelt HJ, Said M, Smulders JF. Lipoedema in patients after bariatric surgery: report of two cases and review of literature. Clin Obes. 2018 Apr;8((2)):147–50. doi: 10.1111/cob.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torre YS, Wadeea R, Rosas V, Herbst KL. Lipedema: friend and foe. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2018 Mar;33((1)) doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0076. /j/hmbci.2018.33.issue-1/hmbci-2017-0076/hmbci-2017-0076.xml. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wold LE, Hines EA, Jr, Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med. 1951 May;34((5)):1243–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-34-5-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct;365((17)):1597–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melby CL, Paris HL, Foright RM, Peth J. Attenuating the Biologic Drive for Weight Regain Following Weight Loss: Must What Goes Down Always Go Back Up? Nutrients. 2017 May;9((5)):E468. doi: 10.3390/nu9050468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapprich S, Dingler A, Podda M. Liposuction is an effective treatment for lipedema-results of a study with 25 patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011 Jan;9((1)):33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgartner A, Hueppe M, Schmeller W. Long-term benefit of liposuction in patients with lipoedema: a follow-up study after an average of 4 and 8 years. Br J Dermatol. 2016 May;174((5)):1061–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peprah K, MacDougall D. Ottawa (ON): 2019. in Liposuction for the Treatment of Lipoedema: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertsch T. E.G., Torio-Padron N., Lipoedema − Myths and Facts Part 4. Phlebologie. 2019;48((01)):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez TL, Kittelson JM, Law CK, Ketch LL, Stob NR, Lindstrom RC, et al. Fat redistribution following suction lipectomy: defense of body fat and patterns of restoration. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 Jul;19((7)):1388–95. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014 Mar;149((3)):275–87. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertsch T. Obesity-related lymphoedema - underestimated and undertreated. Phlebologie. 2018;47((02)):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wollina U, Heinig B. Treatment of lipedema by low-volume micro-cannular liposuction in tumescent anesthesia: results in 111 patients. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2019 Mar;32((2)):e12820. doi: 10.1111/dth.12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]