Abstract

We report 3 patients in California, USA, who experienced multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) after immunization and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. During the same period, 3 adults who were not vaccinated had MIS develop at a time when ≈7% of the adult patient population had received >1 vaccine.

Keywords: multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, viruses, respiratory infections, zoonoses, vaccines, United States, coronavirus disease

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS) in children (MIS-C) and adults (MIS-A) are febrile syndromes with elevated inflammatory markers that usually manifest 2–6 weeks after a severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (1–3). The Brighton Collaboration Case Definition for MIS-C/A was recently published to be used in the evaluation of patients after SARS-CoV-2 immunization (3); some scientists are concerned that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 can trigger MIS-C/A. We report 6 cases of MIS from a large integrated health system in Southern California, USA; 3 of those patients received SARS-CoV-2 vaccination shortly before seeking care for MIS. All 6 patients met the Brighton Collaboration Level 1 of diagnostic certainty for a definitive case and had MIS illness onset between January 15–February 15, 2021. The Chief Compliance Officer for the Southern California Permanente Medical Group reviewed this case series and confirmed that it was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for publication.

The Study

Patient 1 was a 20-year-old Hispanic woman who sought care for 3 days of a diffuse body rash, tactile fever, sore throat, mild neck discomfort, and fatigue. There was no cough, congestion, headache, or abdominal pain. She had vomiting and diarrhea, which had subsided 8 days before admission. She received her first dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 15 days before admission. She had no known coronavirus disease (COVID-19) exposure but was SARS-CoV-2 PCR and nucleocapsid IgG positive. She was hypotensive at arrival to the emergency department, requiring inotropic support. She had elevated troponin and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) with a left ventricular ejection fraction initially mildly reduced at 45% but 30%–35% the following day. She responded well to therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and methylprednisolone (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic, laboratory, and clinical characteristics of 3 patients who had multisystem inflammatory syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 immunization, Southern California, USA .

| Characteristic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y/sex |

20 y/F |

40 y/M |

18 y/M |

| Race/ethnicity |

Hispanic/Latina |

Hispanic/Latino |

Asian/Filipino |

| Underlying conditions |

Asthma |

Depression, hyperlipidemia |

Asthma |

| Symptoms |

Fever and rash for 3 d, diarrhea, vomiting, cardiogenic shock, acute renal failure |

6 d of fevers, malaise, diarrhea, neck pain, headache, lethargy |

3 d of fever, 2 d of abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting and headache |

| Initial vital signs |

Pulse: 130 beats/min, BP 73/56 mm Hg, RR 20 breaths/min, temp 99.4°F, repeat temp 101.4, O2 sats 99% on RA; BMI: 27.85 |

Pulse 102 beats/min, BP 136/88 mm Hg, RR 20 breaths/min, temp 99.2°F, O2 sats 97% on RA; BMI: 28.89 |

Pulse 96 beats/min, BP 98/58 mm Hg, RR 20 breaths/min, temp 97.9°F, sats 97% on RA; BMI: 23.99 |

| Treatment |

Vasopressors × 3 d, IVIG 100 g, methylprednisolone 1 g/d for 3 d, heparin, broad spectrum antibiotics, remdesivir |

Dexamethasone 6 mg/d for 10 d, ceftriaxone, azithromycin, enoxaparin |

IVIG 100 g, methylprednisolone 1 g/d for 3 d, anakinra 100 mg/d for 3 d, broad-spectrum antibiotics, aspirin |

| Imaging |

TTE: normal LV, mildly reduced EF 45% which decreased to 30%–35% the next day; chest radiograph: subtle bibasilar ground glass opacities |

EKG: ST depression and T wave inversion in inferior leads; TTE: normal LV; EF: 50%–55%; CT angiogram: no pulmonary embolism, minimal ground glass opacities |

TTE: normal LV size with mild to moderately reduced EF 40%–45%, right ventricle mildly dilated with normal systolic function; chest radiograph: right pleural effusion; CT abdomen and pelvis: hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, small ascites; pericholecystic fluid; retroperitoneal adenopathy. |

| Length of hospital stay |

8 d |

3 d |

9 d |

| First vaccine |

12 d before symptom onset |

42 d before symptom onset |

19 d before symptom onset |

| Second vaccine |

NA |

4 d before symptom onset |

NA |

| Previously known COVID-19 disease |

No |

34 d before symptom onset |

43 d before symptom onset |

| Initial lab results (reference range) | |||

| Serum leukocytes, × 1,000/mcL (4.5–14.5) | 32.3 | 11.3 | 7 |

| Lymphocytes absolute, × 1,000/mcL (1.5–6.8) | 0.55 | 0.94 | 0.26 |

| Neutrophils absolute, × 1,000/mcL (1.5–8.00) | 31.75 | 12.68 | 6.28 |

| Platelets, × 1,000/mcL (130–400) | 155 | 312 | 63 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (<1.00) | 2.64 | 1.12 | 1.12 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L (<7.4) | 378 | 199.4 | 185.5 |

| D-dimer, µg FEU/mL (<0.49) | 3.01 | 1.15 | 3.44 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL (17–168) | 533 | 1,079.7 | 3,002 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL (218–441) | 801 | 875 | 693 |

| Troponin, ng/mL (<0.03) | 1.54 | 0.37 | 0.06 |

| BNP, pg/mL (<99) | 1,498 | 672 | 106 |

| LDH, U/L (<279) | 251 | 156 | 291 |

| AST, U/L (<34) | 43 | 55 | 59 |

| ALT, U/L (<63) | 28 | 83 | 58 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL (0.0–0.1) | 160.92 | 0.01 | 4.41 |

| SARS-COV-2 nucleocapsid IgG qualitative | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| SARS-COV-2 PCR | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| Blood culture | Negative × 2 | Negative × 2 | Negative × 2 |

| Urine culture | Negative | Not done | Negative (after antibiotics) |

| Bacterial GI PCR panel | Negative | Not done | Negative |

*All patients received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (https://www.pfizer.com). ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; CT, computed tomography; EF, ejection fraction; EKG, electrocardiogram; GI, gastrointestinal; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LV, left ventricle; MR, mitral regurgitation; NA, not applicable; RA, room air; RR, respiratory rate; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; sats, saturations; temp, temperature; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

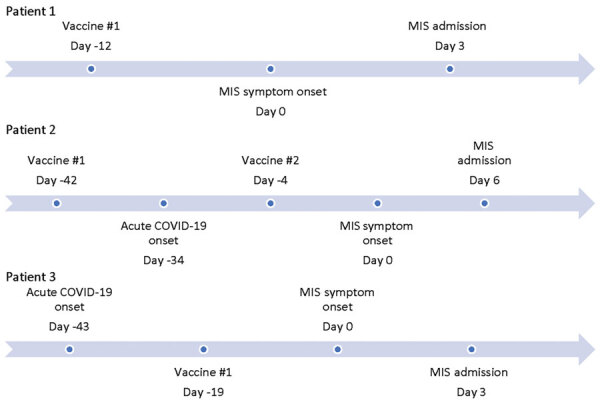

Patient 2 was a 40-year-old Hispanic man who sought care after 6 days of episodic fevers up to 101.7°F. Associated symptoms included dyspnea on exertion, headache, neck pain, lethargy, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. No chest pain was present. He had a history of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and laboratory-confirmed mild to moderate COVID-19, both within 48 days before seeking care (Figure). His exam was notable for sweats, diffuse abdominal pain on palpation, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Patient 2 fulfilled Brighton Level 1 criteria for MIS-A with documented fevers, gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, elevated inflammatory and cardiac markers, and electrocardiogram changes that were concerning for myocarditis (3). He responded well to treatment with dexamethasone (Table 1).

Figure.

Timeline displaying intervals between coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccine, acute COVID-19 symptom onset, and MIS symptom onset in patients in California, USA. MIS, multisystem inflammatory syndrome.

Patient 3 was an 18-year-old Asian American man who sought care at the emergency department with a history of 3 days of fever as high as 104°F with headache, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping (Figure). He denied any upper respiratory symptoms. He had a history of a laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection 6 weeks before the onset of symptoms and received the first dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 18 days before the onset of symptoms. In the emergency department, he was found to be hyponatremic and hypotensive (Table 1). His examination was notable for tachycardia and abdominal tenderness. He had elevated inflammatory markers, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia. Echocardiogram revealed mild to moderate reduced systolic function with an ejection fraction of 40%–45%. He responded well to therapy with methylprednisolone, IVIG, and anakinra.

Patient 4 was a 62-year-old Asian American man who sought care at the emergency department for fever lasting 5 days. For 6 days he had had nausea and vomiting, which developed 23 days after a laboratory-confirmed mild to moderate acute COVID-19 illness that subsided after 1 week. He also had 4 days of bilateral hearing loss. He was hypotensive, requiring inotropic support. He had thrombocytopenia, elevated inflammatory markers, and elevated troponin with diffuse ST elevations on electrocardiogram (Table 2). He responded well to treatment with methylprednisolone, including improvement in his hearing loss.

Table 2. Demographic, laboratory, and clinical characteristics of patients who had multisystem inflammatory syndrome without SARS-CoV-2 immunization, California, USA .

| Characteristic | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/sex |

62 y/M |

29 y/F |

23 y/M |

| Race/ethnicity |

Asian |

Hispanic/Latina |

Hispanic/Latino |

| Underlying conditions |

Hyperlipidemia, gout, atrial fibrillation |

Obesity |

Asthma, obesity |

| Signs and symptoms |

6 d of fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, 4 d of hearing loss; shock, acute renal failure |

4 d of fever, headaches, vomiting, abdominal pain; conjunctivitis, shock,

acute kidney injury |

4 d of fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, cough, SOB; shock |

| Initial vital signs |

Pulse 121 beats/min, BP 112/63 mm Hg, RR 20 breaths/min, temp 101.6°F, O2 sats 98%; within 1 h in ER: BP 70/56 mm Hg, pulse 112 beats/min, RR 28 breaths/ min, O2 sat 97%; BMI: 28.1 |

Pulse 140 beats/min, BP 102/71 mm Hg (61/48 mm Hg after 5 h of being in ER), RR 20, temp 105.2°F, O2

sats 99%; BMI: 31.63 |

Pulse 125 beats/min, BP 87/27 mm Hg, temp 98.2°F, O2 sats 98% on RA;

BMI: 40.3 |

| Treatment |

Vasopressors, methylprednisolone 125 mg every 6 h, broad spectrum antibiotics, enoxaparin |

Vasopressors, methylprednisolone 30 mg every 12 h, IVIG 100 g, heparin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin |

Vasopressors, IVIG 2 g/kg, methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 d, broad spectrum antibiotics |

| Imaging |

EKG: diffuse ST elevation; TTE: mild concentric LVH, mild LV systolic dysfunction, EF 50%; CT angiogram: no evidence of embolus; increased interstitial markings and hazy ground glass changes, small bilateral pleural effusions; 6 mm pericardiac effusion; ultrasound:

right popliteal DVT |

TTE: LVEF 50%–55%, mild TR regurgitation, abdominal CT with colitis and enlarged lymph nodes |

EKG: sinus tachycardia, no ST changes; TTE: LVEF 20%, global hypokinesis, abdominal CT with mesenteric adenitis |

| Length of hospital stay |

7 d |

10 d |

12 d; deceased |

| First vaccine |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Second vaccine |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Previously known COVID-19 |

23 days before symptom onset |

28 d before symptom onset |

38 d before symptom onset |

| Initial lab results (reference ranges) | |||

| Serum leukocytes, × 1,000/mcL (4.5–14.5) | 18.4 | 10.2 | 6.8 |

| Lymphocytes absolute, × 1,000/mcL (1.5–6.8) | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.52 |

| Neutrophils absolute, × 1,000/mcL (1.5–8.00) | 17.66 | 9.66 | 14.35 |

| Platelets, × 1,000/mcL (130–400) | 102 | 170 | 185 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (<1.00) | 2.24 | 0.78 | 2.49 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L (<7.4) | 351.7 | 364.9 | 246.3 |

| D-dimer, µg FEU/mL (<0.49) | 7.21 | 5.79 | >4 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL (17–168) | 5,032 | 606 | 1,273 at admission, >18,000 at its peak 2 days later |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL (218–441) | N/A | N/A | 454 |

| Troponin, ng/mL (<0.03) | 0.85 | 0.06 | <0.02 |

| BNP, pg/mL (<99) | 931 | 331 | 228 |

| LDH, U/L (<279) | 267 | N/A | 224 |

| AST, U/L (<34) | 38 | N/A | 42 |

| ALT, U/L (<63) | 40 | 55 8 | 88 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL (0.0–0.1) | Not done | 8.15 | 29.37 |

| SARS-COV-2 nucleocapsid IgG qualitative | Not done | Positive | Not done |

| SARS-COV-2 PCR | Positive | Negative | Positive |

| Blood culture | Negative x 2 | Negative x 4 | Negative x 9 |

| Urine culture | Negative (after antibiotics) | Negative (after antibiotics) | Negative (after antibiotics) |

| Bacterial GI PCR panel | Not done | Negative | Not done |

*ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; CT, computed tomography; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; EF, ejection fraction; EKG, electrocardiogram; GI, gastrointestinal; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LV, left ventricle; MR, mitral regurgitation; NA, not applicable; RA, room air; RR, respiratory rate; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; sats, saturations; temp, temperature; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram.

Patient 5 was a 29-year-old Hispanic woman who experienced fever, chills, headache, and nausea 28 days after a laboratory-confirmed acute COVID-19 illness. She sought care at the emergency department with hypotension requiring ionotropic support. Clinicians diagnosed MIS-A on the basis of conjunctivitis, evidence of colitis on abdominal imaging, elevated inflammatory markers, lymphopenia, and elevated BNP. She responded well to treatment with methylprednisolone and IVIG (Table 2).

Patient 6 was a 23-year old Hispanic man who experienced fever and abdominal pain 38 days after a laboratory-confirmed mild to moderate acute COVID-19 illness. He was hypotensive, requiring inotropic support. He had mesenteric adenitis on abdominal imaging. He had elevated inflammatory markers, neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and a left ventricular ejection fracture of 20% on echocardiogram. He was treated with IVIG and methylprednisolone (Table 2). He died 12 days after admission.

Conclusions

At the time of our study, our medical group was only vaccinating healthcare workers and patients >75 years of age. The 3 patients that were immunized qualified for early vaccination because they either worked or volunteered in a healthcare setting. These cases occurred ≈1 month after the peak surge of COVID-19 cases in Southern California. At the time these patients sought care, only ≈7% of the adult (>18 years of age) population who were members of the Kaiser Permanente patient group (≈3,776,000 members) had received >1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, whereas 3 of the 6 patients in this study who had MIS were vaccinated. These 6 patients were hospitalized at 5 of the 15 Kaiser Permanente medical centers across Southern California. We believe the temporal association after SARS-CoV-2 immunization is worth noting, given the theoretical concern of MIS-C/A after vaccination (3). We did not identify any patients with MIS after vaccination who did not have recent SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is possible that other case-patients in our member population were hospitalized outside of our 15 medical centers and thus were not captured for this case series.

Overall, MIS is rare in adults. In comparison we treated >50 children with MIS-C during January 2021–February 2021 and >100 since May 2020 among a pediatric population of 960,000.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) allows for vaccination after a SARS-CoV-2 infection after recovery from the acute illness and after the isolation period, with no recommended minimal interval between infection and vaccination (4). Most cases of MIS-C/A occur 2–6 weeks after an exposure or infection (1–3), although we have seen several children brought for care as late as 8–10 weeks after a confirmed infection or exposure. We need to continue to monitor for MIS-C/A after SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunization as more of the population are vaccinated, especially as vaccines are administered to children who are at higher risk for MIS. CDC and the US Food and Drug Administration co-manage VAERS (the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System), which is being used to monitor for adverse events after COVID-19 vaccines. MIS-C/A is listed as a postvaccination adverse event of special interest (5) and should be reported to VAERS (6).

Biography

Dr. Salzman is a pediatric infectious diseases physician and assistant chief of the Department of Pediatrics at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, California. He is also the regional lead physician in pediatric infectious diseases for the Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Salzman MB, Huang C-W, O’Brien CM, Castillo RD. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 July [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2707.210594

References

- 1.Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, Abbo L, Beauchamps L, Balan S, et al. Case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection—United Kingdom and United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1450–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfred-Cato S, Bryant B, Leung J, Oster ME, Conklin L, Abrams J, et al. ; California MIS-C Response Team. California MIS-C Response Team. COVID-19–associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children—United States, March–July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1074–80. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel TP, Top KA, Karatzios C, Hilmers DC, Tapia LI, Moceri P, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults (MIS-C/A): Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2021;39:3037–49; Epub ahead of print. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized in the United States. April 27, 2021. [cited 2021 May 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) standard operating procedure for COVID-19 (as of 29 January 2021). 2021. [cited 2021 May 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/pdf/VAERS-v2-SOP.pdf

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. COVID-19 vaccine EUA reporting requirements for providers. https://vaers.hhs.gov/index.html