Abstract

Background:

African Americans (AA) living in the southeast United States have the highest prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and rural minorities bear a significant burden of co-occurring CVD risk factors. Few evidence-based interventions (EBI) address social and physical environmental barriers in rural minority communities. We used intervention mapping together with community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles to adapt objectives of a multi-component CVD lifestyle EBI to fit the needs of a rural AA community. We sought to describe the process of using CPBR to adapt an EBI using intervention mapping to an AA rural setting and to identify and document the adaptations mapped onto the EBI and how they enhance the intervention to meet community needs.

Methods:

Focus groups, dyadic interviews, and organizational web-based surveys were used to assess content interest, retention strategies, and incorporation of auxiliary components to the EBI. Using CBPR principles, community and academic stakeholders met weekly to collaboratively integrate formative research findings into the intervention mapping process. We used a framework developed by Wilstey Stirman et al. to document changes.

Results:

Key changes were made to the content, context, and training and evaluation components of the existing EBI. A matrix including behavioral objectives from the original EBI and new objectives was developed. Categories of objectives included physical activity, nutrition, alcohol, and tobacco divided into three levels, namely, individual, interpersonal, and environmental.

Conclusions:

Intervention mapping integrated with principles of CBPR is an efficient and flexible process for adapting a comprehensive and culturally appropriate lifestyle EBI for a rural AA community context.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Community-based participatory research, Evidence-based intervention, Intervention mapping, African Americans, Rural population

CVD is a leading cause of death in the United States. Randomized controlled trial data have documented the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions to prevent CVD.1 A Cochrane Review found of 55 trials from 1998 to 2006 concluded that lifestyle interventions may reduce mortality among individuals at high CVD risk.1 However, few of these interventions were conducted among AA in the rural Southeast.2 Overall, AAs have poorer cardiovascular health and increased CVD mortality rates compared with non-Hispanic Whites.2 There is a pressing need for research to inform adaptation and implementation of evidence-based CVD preventions in new settings or with different populations.3–5

Adaptation of EBI for implementation in rural AA communities is especially necessary because most EBIs have been tested in urban settings.2,3 However, rural and underserved communities have different social, cultural, and environmental factors that influence lifestyle behaviors that must be accounted for when implementing interventions in these settings.6

Widespread implementation of EBIs has been hampered by ongoing tension about the distinction between adaptation and fidelity.3 A common assumption with intervention development has been that deviation from a manualized intervention will reduce the intervention’s effectiveness.3 However, various components of an intervention may need adaptation to improve the fit and effectiveness within a new setting and/or population. Stakeholder engagement is critical when adapting and implementing interventions in disparity populations who may have been under-represented in the research that generated the evidence.6,7

Despite calls for greater transparency, few studies have described a systematic and structured approach to describing and justifying adaptations to EBIs.8 Intervention mapping has been used primarily to develop (de novo) interventions; although notable examples exist, intervention mapping has generally not been used to adapt EBIs.9 Intervention mapping provides a stepwise process—from needs assessment to evaluation—that can be used to guide comprehensive adaptation of interventions.10–14 Our study aims are twofold: 1) to describe how we used CBPR and intervention mapping approaches to adapt an evidence-based CVD prevention intervention for rural AA communities and 2) to document the adaptations using a rigorously developed coding framework.14

METHODS

Partnership and Setting

Growing, Reaching, Advocating for Change and Empowerment (Project GRACE) is a partnership in North Carolina between community organizations and academic researchers, “to develop culturally relevant prevention interventions in a rural AA community.”15 GRACE is anchored in two predominantly AA and low-income rural counties in eastern North Carolina (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The GRACE partnership involves a consortium of academic and community partners, with representatives from local community, faith-based, health, and social service organizations.6 The current study included one academic and two community partners (the executive directors from a community-based and faith-based organization) as principal investigators. Community partners were involved in all aspects of the study, including study design, adaptation, implementation, data collection, and evaluation. Our study has undergone ethics review and was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board (reference number 13–2576).

Through strategic planning sessions, the GRACE partnership determined that CVD was a health priority and sought to implement a CVD prevention intervention. After conducting a literature review of potential EBIs, PREMIER, a multicomponent behavioral lifestyle change intervention, was chosen because 1) the manualized intervention was readily available for adaptation and implementation, 2) it focused on ensuring cultural relevance for AAs, and 3) it was effective in reducing blood pressure among AAs using behavioral strategies that could be applied to address multiple CVD risk factors.8,16 Despite these strengths, community partners expressed concerns about the intervention fit for implementation in their local context. PREMIER had been tested in large academic centers and clinical settings with trained paraprofessionals, in comparison with our planned intervention context, which was small rural communities with lay community health workers. To identify the necessary adaptations, we established a subcommittee of community and academic partners to lead the process. The subcommittee met in-person at least monthly (more frequently on an ad hoc basis) to complete intervention mapping tasks. The final adapted version of our intervention was named “Heart Matters” by the partnership.

Within the adaptation subcommittee, we formed groups to focus on specific aspects of the adaptation process (i.e., recruitment, intervention content and delivery, evaluation). These groups met weekly and were co-led by a community and academic partner. To make adaptation decisions, co-leads of ad hoc groups would report a summary to the larger adaptation subcommittee about required decisions. Owing to the nature of their role, community partners typically focused their attention on feasibility and acceptability. In contrast, the academic partners focused on potential threats to intervention fidelity. To make final decisions, the subcommittee would attempt to build a consensus. If the adaptation subcommittee could not reach a consensus, the three principal investigators would deliberate and either reach a consensus themselves or revert to majority rules. This process was used across all stages of the intervention mapping process, and status updates were provided to the GRACE steering committee regularly.

Description of PREMIER

PREMIER is a behavior change intervention focused on goal setting for diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption, developing action plans for change, and monitoring progress toward goals. PREMIER used a combination of seven individual and 26 group-based education sessions implemented by trained professionals.5,16 The 2-hour group sessions included time for checking in, tasting new foods, learning new behaviors, social interaction, and discussion of shared experiences. The 60-minute individual sessions were conducted in person, using motivational interviewing techniques. PREMIER was evaluated using a randomized control trial design with three arms: advice only, comprehensive lifestyle, and comprehensive lifestyle plus the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.5,16

Intervention Mapping and Adaptation Coding Framework

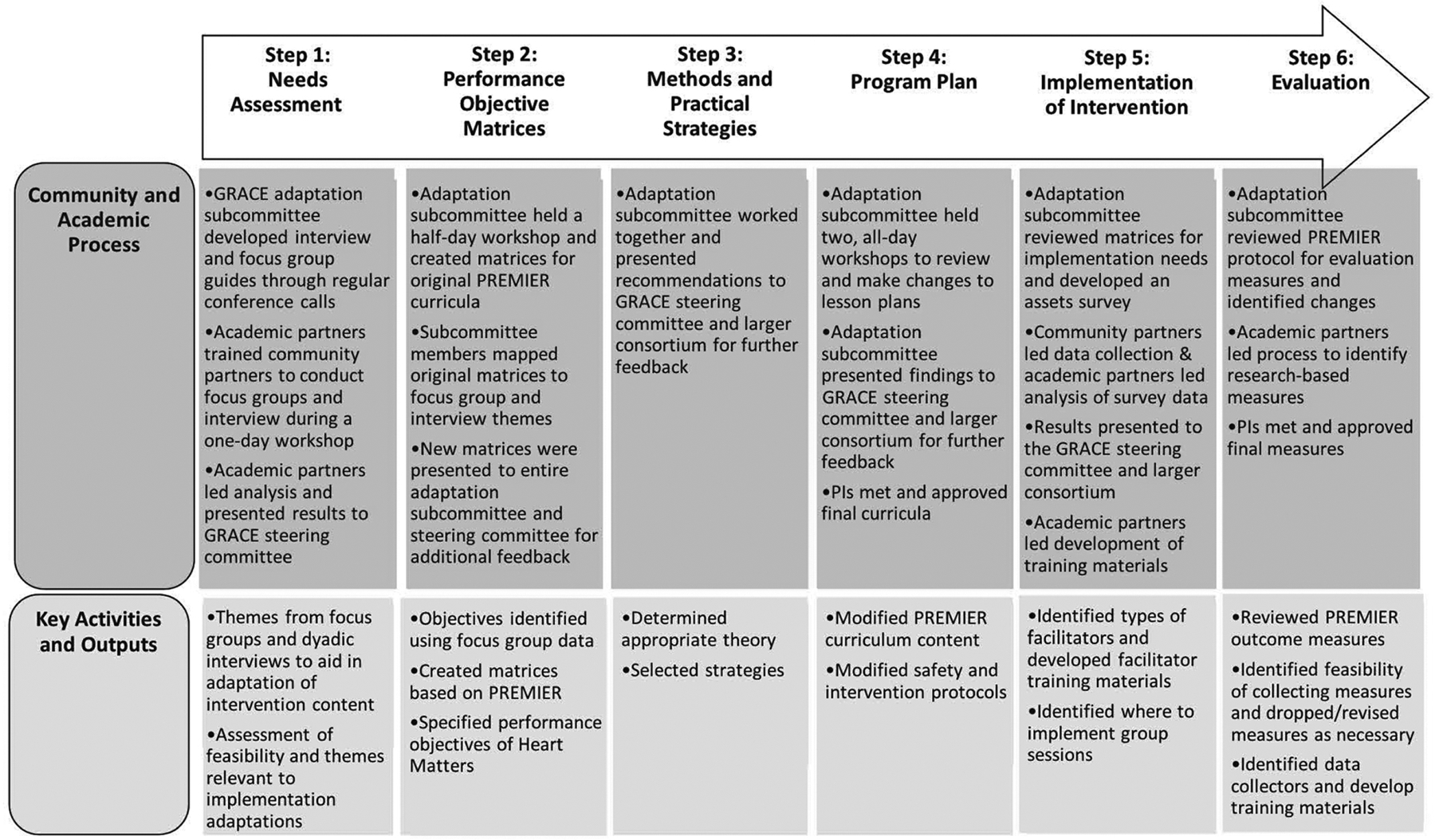

We used the six-step intervention mapping process (Figure 1) to adapt PREMIER.

Figure 1.

Intervention mapping process with a CBPR approach.

-

Step 1: Needs Assessment. We collected and analyzed data from focus groups (n = 8) and semi structured individual interviews (n = 48) to inform adaptation of the intervention. The focus groups and the interviews were conducted with participants who were potentially eligible for the intervention. The criteria included 1) AA men and women 21 and older, 2) residing in the GRACE partnership catchment area, and 3) having at least one CVD risk factor (hypertension, obesity, etc.). Trained community partners moderated the focus groups and interviews. The focus group and interview guides contained questions regarding the acceptability of session frequency, session duration, and use of mobile technology. The guides also included questions that assessed barriers to participating in the sessions and to lifestyle behavior change. However, only the interview guide included additional questions about the role of families, a culturally relevant context in AA communities, in the intervention. Additional details about the interviews have been published elsewhere.17

All focus groups and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The adaptation subcommittee conducted thematic analysis of the transcripts.18 The committee reviewed the interview and focus group transcripts and developed a codebook. Next, the researchers and community partners worked in pairs to code the transcripts. The partnership used group discussions and consensus to address code disagreements. Lead researchers reviewed the coded data and noted emerging and related concepts across the codes and developed themes that were used to inform development of the program objective matrices.

-

Step 2: Developing Matrices. First, the adaptation subcommittee reviewed the goals and objectives of PREMIER and created program objective matrices that reflected the original intervention. Second, the subcommittee reviewed PREMIER’s performance objectives to assess their importance and relevance to the community and their consistency with themes from our focus groups and interviews. When our emergent themes did not reflect one of the performance objectives for PREMIER, we created a new performance objective to reflect the theme. After reviewing all curriculum sessions, we compiled a comprehensive list of objectives by content area (e.g., physical activity, diet) and determinant (e.g., knowledge, skills).

Table 1 presents a sample matrix of the PREMIER performance objectives (bold text), their determinants, and the Heart Matters objectives we identified based on our qualitative data analysis. Typical of intervention mapping matrices, some fields are empty because not every determinant needed to be addressed to meet the objectives.

Step 3: Theory-Based Methods and Practical Strategies. PREMIER was developed based on multiple theories and strategies including social cognitive theory, behavioral self-management techniques, relapse prevention model, and the transtheoretical model.5,16 Since the intervention strategies used in PREMIER were theory driven, we did not make any adaptations to the strategies used.

Step 4: Program Plan. After we developed performance objective matrices, we edited all PREMIER’s lesson plans to address the new objectives and any community concerns. The adaptation subcommittee held two day-long sessions to review and modify PREMIER’s program objective matrices. During these sessions, the adaptation subcommittee members worked in pairs (one academic and one community partner) to review all PREMIER curricula materials to identify content to add, change, or delete.

Step 5: Adoption and Implementation. In addition to information obtained from the focus groups, the adaptation subcommittee used a community assets and network survey to help guide our adaptations. The goals of the survey were to understand the resources available in the community to support implementation. To identify our sample of community- and faith-based organizations, community partners, we reviewed a list of nonprofit and service organizations in the region (n = 432) available from the National Center for Charitable Statistics and excluded organizations that did not provide health-related or social services, were defunct, had invalid contact information, or were outside the defined area. This resulted in a total of 89 organizations in the two-county region that were asked to complete an online survey about the types of services provided, populations served, interest in implementing CVD prevention interventions and, if any, collaborators in their CVD prevention work. One representative from each organization was asked to respond and a total of 54 organizations (60.7%) completed the survey.

Step 6: Evaluation. The final step involved outlining changes to the evaluation plan. The adaptation subcommittee reviewed the PREMIER protocol and assessed feasibility, acceptability, and relevance of the measures for our target community. Implementation of Heart Matters began in June of 2016 and was evaluated using a cluster randomized controlled trial to compare the Heart Matters intervention to a delayed intervention control arm. Outcome data collection from the trial concluded in December of 2018, and analysis is currently underway.

Table 1.

Heart Matters Matrix Snapshot

| Performance Objectives (Individual Participants) | Knowledge | Motivation/Attitudes | Skills | Self-efficacy | Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Set goals for physical activity (goal setting) | |||||

| P.1.1 Identify the connection between physical activity and CVD* | K.1.1. Explain how physical activity influences the risk of CVD* | — | — | — | — |

| 1.2 Identify the type of physical activity best fit for personal needs | K.1.2. Explain types of physical activity levels and (understand what physical activity is and what counts; low, moderate, high)† | — | S.1.1. Practice different forms of physical activity | — | — |

| 1.3. Set realistic weekly action plans | — | — | S.1.2. Demonstrate use of templates to create action plans | — | — |

| 1.4. Set long-term goals | — | M.1.3. Feel positive about the potential long-term benefits of regular exercise | S.1.3. Demonstrate use of templates to set goals | — | — |

| 2. Monitor and track physical activity levels (self-monitoring) | |||||

| 2.1. Identify a paper or electronic log to track physical activity | K.2.1. Explain the types of logs available and advantages/disadvantages of each | — | — | — | — |

| 2.2. Track activity types, duration, etc. each day | — | M.2.2. Feel positive that the time to track activity will help them accomplish their goals | S.2.2. Demonstrate use of a log to track activity (Focus Group: Use of technology such as “Map my Run”)† | — | — |

Focus groups/interview themes identify new needs for intervention (not currently covered by PREMIER).

Focus groups/interview themes align with existing PREMIER intervention 1.

No theme identified (intentionally empty).

Coding Framework

We documented adaptations to the intervention using a coding framework developed by Wiltsey Stirman et al.,14 designed to systematically categorize and document adaptations. Guided by this framework, the adaptation subcommittee reviewed all changes made to PREMIER through the intervention mapping steps and answered the following questions: 1) what is the modification? 2) by whom were the modifications made? 3) at what level of the delivery and in what context were the modifications made? and 4) what was the nature of the content modification? We categorized each modification as either tailoring/tweaking refining, shortening/condensing (of the intervention or intervention sessions) and adding elements.14 Tailoring/tweaking refining is defined as any minor change to their intervention that leaves the major intervention principles and techniques to increase the appropriateness, acceptability, or applicability.14 Shortening/condensing (pacing/timing) is defined as using a shorter amount of time than allotted to complete the session or intervention sessions.14 This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Table 2 provides an overview of key changes to content, context, training, and evaluation, as defined below.

Table 2.

Overview of the Original PREMIER EBI and Documentation of Adaptations for Heart Matters Using the Wiltsey-Stirman et al. Coding System

| Description of Original PREMIER Content | Description of Heart Matters Content | Level of Adaptation | Type of Adaptation | Source/s of Adaptation (community partner input, focus groups, | Relevant Intervention Mapping Step Coinciding with Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content modifications: changes made to the intervention procedures, materials or delivery | |||||

| Curricula behavioral goals | |||||

| Reduce weight by 4.5 kg (10 lb) or more if overweight Limit daily sodium intake to 100 mmol or less Limit fat intake to 30% or less of total kcal No more than 1.0 ounce of alcohol per day for men, and no more than 0.5 ounces of alcohol per day for women Engage in 180 minutes per week or equivalent of moderate physical activity |

If recommended, lose 15 lbs, or your individualized goal Eat 2,400 mg or less of sodium every day Eat 30% or less of total calories from fat No more than two alcoholic drink per day for men, and no more than one alcoholic drinks per day for women Be physically active for 30 minutes per day, three days per week, or accumulate 180 minutes of moderate-intensity each week |

Population | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Community partner input PREMIER had challenging behavior change and health outcome goals Participants may be discouraged if goals are unrealistic |

Step 2: performance objective matrices |

| Intervention dose/duration | |||||

| Fourteen 120-minute group sessions and four individual sessions in first 6 months of intervention Twelve group sessions and three individual sessions for 12 months following first 6 months |

Fourteen 90-minute group sessions and four individual sessions in first 6 months 12 group sessions and three individual sessions for 6 months after the first 6 months |

Cohort | Shortening/condensing | Focus group Participants preferred sessions be no longer than 90 minutes Participants preferred a 6- to 12-month intervention |

Step 4: program plan |

| Curricula components and materials | |||||

| No content/curricula components specifically for adults with mobility limitations Social support emphasized during the maintenance phase only. |

Added special curricula that gives adults with mobility issues strategies for physical activity Family and friends from same household allowed to attend all group session with participant |

Individual population | Adding elements | Focus group Participants expressed the need for modifications for physical activity for those with limited mobility Participants expressed an interest in having family and friends also participate in the intervention for social support |

Step 4: program plan |

| Time for group to taste, compare, and discuss different foods discussed during the group session Handouts and participant materials relevant to urban population |

Modified sample food to make it more culturally appropriate and ensure availability in community Handouts and materials amended to reflect relevancy and applicability to rural population |

Population | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Community partner input Community partners expressed that foods should be types that participants would be most likely to incorporate into their daily diets and materials provided would need to be relevant to a rural community |

Step 4: program plan |

| Check-in activity rigid with strict time constraint | Check-in structure and time constraints were loosened | Population | Loosening structure | Community partner input Community partners suggested a shortened check-in to accommodate other session needs |

Step 4: program plan |

| Context: changes made to delivery of the same program content, but with modifications to the format or channel, the setting or location in which the overall intervention is delivered, the personnel who deliver the intervention, or the population to which an intervention is delivered. | |||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | |||||

| Excluded prediabetics Excluded individuals with hypertension |

Included prediabetics Included those with hypertension |

Population | Loosening structure | Academic and community partner input Results of pre-eligibility screening found majority of eligible participants were prediabetic and diabetic In order to have a large enough pool of participants and reach adequate numbers of the community, we revised eligibility criteria |

Step 4: program plan |

| Intervention delivery | |||||

| Primarily delivered to AA and White populations living in urban areas | Delivered exclusively to AAs living in a rural and semiurban area | Population | N/A | N/A; by nature of our objective the population was different | Step 5: implementation of intervention |

| Group sessions delivered at specialized clinical treatment centers Individual one-on-one counseling sessions designed to be delivered in person |

Delivered at communityand faith-based organization facilities Individual sessions amended to be conducted over the phone by facilitators |

Setting | Integrating the intervention into another setting | Community partner input, community assets survey Mistrust in and discomfort of community members with health care institutions Implementation via communityand faith-based organizations would provide improve reach and acceptability Community partners suggested in-person would be difficult owing to time and travel constraints; phone sessions would be convenient for both facilitators and community members |

Step 5: implementation of intervention |

| Delivered by staff at specialized centers | Delivered by lay community members | Personnel | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Community partner input Community partners indicated that the facilitator should be someone relatable in order to ensure retention of participants |

Step 5: implementation of intervention |

| Training and evaluation: changes made to the procedures for training personnel or evaluating the program | |||||

| Study design and procedures | |||||

| Intervention evaluated using a RCT design with three arms | Intervention evaluated using a delayed intervention control RCT design with two arms | Evaluation | Academic and community partners Academic partners expressed budgetary and recruitment constraints Community partners expressed concerns with equitable resources provided to the participants |

Step 6: evaluation | |

| Multiple recruitment screening sessions; participants had to meet certain cut-offs to continue through eligibility | One recruitment screening session | Evaluation | Community partner input Community partners expressed concern about participant burden with multiple screening sessions |

Step 6: evaluation | |

| Evaluation measures | |||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure Data collected at 7 timepoints; prescreening visit, screening visit, baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months |

Weight is primary outcome Four data collection timepoints; baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months |

Evaluation | Academic and community partner input Owing to changes in the inclusion criteria (i.e., inclusion of individuals on blood pressure medications), blood pressure was no longer appropriate Academic partners Resource limitation and participant burden |

Step 6: evaluation | |

Content

Content modifications focused on how the intervention was being delivered.14 We identified 12 content changes, one at the individual level and the rest at the population level. The majority of the modifications focused on three main areas: 1) lifestyle behavioral goals, 2) curricular content, and 3) intervention session length. The performance objectives matrix developed in step 2 helped to identify the changes and additions that were made to the curricula content. For example, owing to focus group comments about the need for southern and culturally appropriate healthy foods, we included a new skill objective for the dietary goals: “Be able to prepare healthy southern cuisine.” Based on this, the Taste It! component of the PREMIER curricula included more culturally appropriate, locally available, and affordable foods. As another example, we identified the need for additional objectives regarding interpersonal support throughout the curricula. The original curricula encouraged participants to reach out for social support, but household members of PREMIER participants were excluded from participating in intervention group sessions until the maintenance phase (after 6 months). However, our focus group participants noted the importance of family support in changing health behaviors, prompting us to modify our eligibility criterion to allow individuals residing in the same household to participate in the intervention.

Finally, based on focus group feedback, we shortened and condensed the overall length of the group sessions and intervention duration. A major theme from the focus groups was that busy and fixed work schedules would make it difficult to attend 2-hour sessions. Thus, we shortened the duration of the group sessions to 90 minutes by condensing and altering the structure of a check-in activity for efficiency. Focus group participants also raised concerns about committing to 18 months of intervention activities. PREMIER group sessions were held weekly for 3 months, every other week for the next 3 months, and monthly for the final 12 months. In contrast, we revised our protocol to make Heart Matters a 12-month intervention, which included weekly sessions for the first 2 months and biweekly session for the remaining 10 months. The seven individual sessions in PREMIER were not changed.

Our collaborative approach helped us gain insights that optimized context adaptations for implementation. For example, through our community assets and network survey we discovered a major hospital that was central to the organizational collaborative structure. This finding suggested that the hospital was a potential setting for intervention implementation; however, community partners provided important insight about how the constellation of community- and faith-based organizations in the area provided more accessible and acceptable venues.

Context

Context refers to changes in the format, setting, personnel, and population.14 We identified a total of six context changes based on community partner input, our qualitative findings, and the community assets and network survey findings. At the population level, several adaptations were made to the eligibility criteria. Our intervention targeted AAs living in a rural and semiurban area, whereas PREMIER had targeted a more urban and mixed race population.19 Because of the high prevalence of CVD risk factors in our target communities, our community partners were concerned that there would be too few AAs who would meet eligibility criteria, largely owing to the high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in the target communities. Thus, we conducted a pilot of the eligibility criteria used in PREMIER to assess the feasibility of recruiting the necessary study sample size. Out of 78 individuals screened using the PREMIER eligibility criteria, we found that only 24% would have been eligible. Most of the individuals screened during our pilot for the Heart Matters intervention were ineligible because they were diabetic (hemoglobin A1c of >7) or currently taking medication to control blood pressure. Thus, we expanded the eligibility criteria to allow prediabetics and individuals taking medications to control blood pressure to enroll.

We also revised the format of individual counseling sessions based on our qualitative data. PREMIER delivered one-on-one individual counseling sessions in person; however, we modified the protocol to allow the facilitators to conduct individual sessions by phone, to combat the challenge of transportation in rural underserved communities. In addition, our intervention was delivered in local community and faith-based settings, whereas PREMIER was primarily delivered in academic medical centers. We used information obtained from the community assets and network survey to identify organizations well-situated in the community and with an interest in hosting the groups sessions. In addition, to enhance participant retention, we provided transportation to and childcare during group sessions.

Finally, we made changes to the intervention personnel. It was important to community and academic partners that participants be comfortable with the facilitators but also have access to trained professionals in lifestyle behavior change counseling. Thus, we trained lay community members (e.g., teachers and retired professionals) as the core intervention facilitators, and identified a cadre of specialized experts (i.e., nutritionists, registered nurses, and personal trainers) to help facilitate specific sessions and activities. Our collaborative CBPR approach helped us understand the importance of bridging cultural adaptations with implementation science.

Training and Evaluation

Training and Evaluation refers to changes that occur “behind the scenes” and do not affect the content or context of delivery. We trained our staff in the same three areas as described by the PREMIER protocol16: content and delivery of the intervention, facilitation of the group process and behavior change, and trial-specific procedures for data collection and reporting. However, PREMIER’s published protocols did not contain enough depth or detail (e.g., specific training strategies, intensity of the training) for us to ascertain if and how our training compared. While PREMIER evaluated the comparative effectiveness of three study arms: information only, comprehensive intervention, and comprehensive intervention plus the DASH diet, our community partners expressed discomfort with a randomized design where some participants would not receive the full intervention. They also raised concerns about participants’ understanding and acceptability of following the DASH diet (e.g., tracking sodium and fat intake). Thus, we used a cluster randomized trial design with two arms: comprehensive intervention and delayed comprehensive intervention.

DISCUSSION

We described the application of a CBPR-informed intervention mapping approach to adapt an evidence-based CVD prevention intervention for a rural, AA community. Our study yields two key findings relevant to implementing interventions to reduce and address health disparities.20 First, adaptation should include community stakeholder input to ensure fit with the implementation context. Second, implementation of interventions in rural and underserved racial groups may require trade-offs that highlight the tension between adaptation and fidelity.

For implementation of EBIs to be successful and the intervention to be effective, the implementation protocols must take into account the preferences and priorities of those who will deliver and implement the intervention as well as meet the needs of study participants.20 Stakeholder engaged formative research allows investigators to identify facilitators and barriers to study participation and use this information to guide intervention development. Our use of a CBPR approach to intervention mapping allowed us to identify changes at the surface level (e.g., tailoring messages, content to include local preferences) and deep level (e.g., changing delivery options to reflect cultural norms and values)14 and to make changes to our training and evaluation protocols to improve the feasibility of implementing an EBI in a new context. CBPR approaches complement qualitative research, providing an opportunity for substantive input from community members that may be instrumental to shaping the research.21 In addition, collaborating with local stakeholders on adaptation increases the potential for sustainability of the intervention.

Our study shares features of pragmatic trials and provided important information on practical aspects of implementation, including eligibility criteria, organizational resources, flexibility in delivery and adherence.22 To enhance the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in a rural, AA community, we modified our inclusion criteria, study design, and some aspects of our implementation and evaluation to fit the needs and priorities of our community. We used CBPR and intervention mapping to guide our adaptations. There is no gold standard for how adaptations should be made. The current evidence for intervention adaptations is inadequate to provide guidance on when adaptations should be made to an EBI.3

A key challenge we encountered was managing trade-offs between adaptations and fidelity. The tension between fidelity and adaptation is a recurrent theme in implementation literature and changes to EBIs can pose a threat to internal validity.7,23,24 We used our collaborative adaptation process to identify intervention core components and consider multiple fidelity and adaptation trade-offs. Primarily, we had to balance community expertise regarding adaptations they felt were necessary to enhance feasibility of implementation with the academic team members’ concerns regarding maintaining fidelity. Although we had a systematic process to weigh the various opinions and suggestions and create a balance of power, a clear decision was not always evident and the collaborative decision-making process sometimes resulted in delays.

A key strength of our study was the systematic process used to identify and characterize the adaptations. Other studies have noted the benefit of intervention mapping to help retain core elements of the EBI and document adaptations.10,11 In addition, the Wiltsey Stirman coding framework allowed us to systematically characterize the scope and extent of the adaptations; thereby, enhancing transparency and replicability.

CONCLUSIONS

EBIs have been shown to promote behavior change; however, evidence of effectiveness does not ensure successful implementation. Evaluation and adaptation of implementation protocols based on stakeholder input is critical for success. Implementation often requires addressing important contextual factors that impact both the recipients of the intervention as well as those who deliver the implementation. Our use of intervention mapping integrated with principles of CBPR and the Wiltsey Stirman classification system allowed us to rigorously adapt and document changes to a CVD prevention intervention for implementation with rural AAs at high risk for CVD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the Project GRACE consortium and steering committee, UNC Center for Health Equity Research staff, Project Momentum, Inc. staff, James McFarlin Community Development, Inc. staff, supporting organizations (St. James Missionary Baptist Church and Visions, Inc.), and hosting sites (Community Enrichment Organization, Ebenezer Baptist Church, Twin County Elks Lodge, and Helping Hands).

This study is funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (grant numbers 1R01HL120690 & 2K24HL105493; PI Giselle Corbie-Smith).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD001561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall WD, Ferrario CM, Moore MA, Hall JE, Flack JM, Cooper W, et al. Hypertension-related morbidity and mortality in the Southeastern United States. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313(4):195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers DA, Norton WE. The adaptome: Advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51 (4 Suppl 2):S124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer-Wreder L, Sundell K, Mansoory, S. Tinkering with perfection: Theory development in the intervention cultural adaptation Field. Child Youth Care Forum. 2012;41(2):149–71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci. 2004;5(1):41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valdez CR, Stege AR, Martinez E, Dcosta S, Chavez T. A community-responsive adaptation to reach and engage Latino families affected by maternal depression. Family Process. 2017; 57(2):539–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Writing Group of the PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results for the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Dongen EJ, Leerlooijer JN, Steijns JM, Tieland M, de Groot LC, Haveman-Nies A. Translation of a tailored nutrition and resistance exercise intervention for elderly people to a real-life setting: Adaptation process and pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Kroon ML, Bulthuis J, Mulder W, Schaafsma FG, Anema JR. Reducing sick leave of Dutch vocational school students: Adaptation of a sick leave protocol using the intervention mapping process. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(9):1039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Highfield L, Hartman MA, Mullen PD, Rodriguez SA, Fernandez ME, Bartholomew LK. Intervention mapping to adapt evidence-based interventions for use in practice: increasing mammography among AA women. BioMed Res Int. 2015; 2015:160103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabassa LJ, Gomes AP, Meyreles Q, Capitelli L, Younge R, Dragatsi D, et al. Using the collaborative intervention planning framework to adapt a health-care manager intervention to a new population and provider group to improve the health of people with serious mental illness. Implement Sci. 2014;9(178). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leerlooijer JN, Ruiter RA, Reinders J, Darwisyah W, Kok G, Bartholomew LK. The World Starts With Me: Using intervention mapping for the systematic adaptation and transfer of school-based sexuality education from Uganda to Indonesia. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(2):331–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8(65). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbie-Smith G, Adimora A, Yoummans S, Muhammad M, et al. Project GRACE: A staged approach development of a community-academic partnership to address HIV in rural AA communities. Health Promot Pract. 2001;12(2):293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research. PREMIER: A trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control. Available from: https://research.kpchr.org/Research/Research-Areas/Cardiovascular-Disease/PREMIER

- 17.Ellis KR, Young TL, Carthron D, Simms M, McFarlin S, Davis KL, Dave G, et al. Perceptions of Rural African American adults about the role of family in understanding and addressing risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33:708–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. (2003). Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6,42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger J, Allen C, Cheadle A, Ciske S, Schier JK, Senturia L, et al. Using community-based participatory research to address social determinants of health: Lessons learned from Seattle Partners for Healthy Communities. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):361–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford I, Norrie J (2016). Pragmatic trials. N Engl J Med. 375(5):454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horn K, McCracken L, Dino G, Brayboy M. Applying community-based participatory research principles to the development of a smoking-cessation program for American Indian teens: “Telling our story.” Health Educ Behav. 2006;35(1):44–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peplow D, Augustine S. Intervention mapping to address social and economic factors impacting indigenous people’s health in Suriname’s interior region. Global Health. 2017:13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]