Abstract

Mitochondria play key roles in the differentiation and maturation of human cardiomyocytes (CMs). As human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) hold potential in the treatment of heart diseases, we sought to identify key mitochondrial pathways and regulators, which may provide targets for improving cardiac differentiation and maturation. Proteomic analysis was performed on enriched mitochondrial protein extracts isolated from hiPSC-CMs differentiated from dermal fibroblasts (dFCM) and cardiac fibroblasts (cFCM) at time points between 12 and 115 days of differentiation, and from adult and neonatal mouse hearts. Mitochondrial proteins with a twofold change at time points up to 120 days relative to 12 days were subjected to ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA). The highest upregulation was in metabolic pathways for fatty acid oxidation (FAO), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and branched chain amino acid (BCAA) degradation. The top upstream regulators predicted to be activated were peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (PGC1-α), the insulin receptor (IR), and the retinoblastoma protein (Rb1) transcriptional repressor. IPA and immunoblotting showed upregulation of the mitochondrial LonP1 protease—a regulator of mitochondrial proteostasis, energetics, and metabolism. LonP1 knockdown increased FAO in neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (nRVMs). Our results support the notion that LonP1 upregulation negatively regulates FAO in cardiomyocytes to calibrate the flux between glucose and fatty acid oxidation. We discuss potential mechanisms by which IR, Rb1, and LonP1 regulate the metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS and FAO. These newly identified factors and pathways may help in optimizing the maturation of iPSC-CMs.

Keywords: cardiac differentiation, human induced pluripotent stem cells, mitochondria, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) can be differentiated into the cardiac lineage (45, 81), representing a renewable source of human cardiomyocytes (CMs) for studying and potentially treating cardiac diseases (81). hiPSC-CMs provide a research model for investigating the mechanisms underlying cardiac development and maturation, as well as patient-specific physiology and drug responsiveness (28, 81). The majority of protocols yield developmentally immature CMs (45, 59). However, it has been shown that ultrastructural maturation of hiPSC-CMs can, in fact, be observed in long-term cultures (28). Moreover, recent work has emerged demonstrating that advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue from iPSC-CMs can be induced by early-stage electromechanical training of these cells in culture (60). Thus, a greater understanding of the mechanisms and pathways that promote differentiation and maturation of iPSC-CMs is crucial to achieving their translational potential. Previous work profiling hiPSC-CMs was conducted primarily using microarray-based gene expression assays (71). Thus far, the majority of proteomic studies have examined the global cellular proteomes of embryonic stem cell-derived CMs (hESC-CMs) (34, 35, 54) or hiPSC-CMs (25, 31, 70).

Mitochondria are critical regulators of CM development and differentiation, as they are essential for coordinating cellular energetics and metabolism. In adult CMs, mitochondria occupy ∼30%–40% of cell volume (3, 29, 49, 63). Changes in cardiac mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetics coincide with myocyte differentiation and cardiac morphogenesis (43). Upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) promotes cardiac maturation (55). By contrast, mitochondria in hiPSC-CMs at early stages of differentiation have not yet established an extensive morphological and functional network. Increased mitochondrial biogenesis, membrane potential, and respiratory complex activities have been observed during prolonged (>100 days) in vitro culturing of hiPSC-CMs (15). However, to date, very few studies have focused on the mitochondrial proteome of differentiating hiPSC-CMs (15, 70), since obtaining mature CMs is still challenging.

To gain a better understanding of the mitochondrial proteins and pathways participating in the physiological transitions that occur during CM differentiation and maturation, we have studied the mitochondrial proteomes of hiPSC-CMs derived from dermal fibroblasts (dFCM) and cardiac fibroblasts (cFCM); for comparison, we also analyzed the mitochondrial proteomes of neonatal and adult mouse hearts. A combination of proteomics and bioinformatics was used in this analysis. Our study identifies novel upstream regulators and pathways along with known pathways and regulators of metabolic differentiation, which are either activated or inhibited during the in vitro differentiation of hiPSC-CMs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

hiPSC line derived from human cardiac fibroblasts (cF) was generated in our laboratory using the Sendai virus reprogramming system (Invitrogen) (Supplemental Fig. S1A; all Supplemental Figures are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11832837.v7). These cells were transduced with a lentivirus green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene under the control of the cardiac promoter sequences of Myh6. Myh6-eGFP-Rex-Neo was purchased from Addgene (Addgene plasmid no. 21229; RRID:Addgene_21229). hiPSCs derived from dermal fibroblasts were acquired from the Coriell Institute (GM23338). The hiPSCs were maintained in mTESR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies), in six-well plates coated with hESC-qualified Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Cells were passaged at a 1:36 dilution in six-well plates every 5–7 days. They were disaggregated with Versene (Life Technologies). Five-micromolar ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) was used to ensure optimal attachment. Under these nondifferentiating conditions, hiPSCs express pluripotent markers TRA-1–60, Oct3/4, and hNanog (Supplemental Fig. S1, B and C).

CM Differentiation

CM differentiation was performed according to a published method using the GSK inhibitor CHIR99021 and Wnt inhibitor IWP-2 (GiWi protocol) (39), modified with the addition of ROCK-specific inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM) until day −2 (2). Briefly, hiPSCs and hESCs (WA07, WiCell) were cultured on Matrigel-coated six-well plates in mTeSR1 medium. Cells were resuspended in mTeSR1 with the ROCK-specific inhibitor Y-27632 (5 μM, R&D Systems) and plated at varying cell densities. On day 0, when the cells reached 50%–60% confluency, the medium was aspirated and the cells were incubated twice with Matrigel overlay (MO) for 15 min before being treated with the GSK inhibitor CHIR99021 (10 μM, Selleck Chemicals) in RPMI/B27 (Life Technologies) without insulin (82). On day 3, the cells were treated with MO and Wnt inhibitor IWP2 (5 μM, R&D Systems) in RPMI/B27 without insulin. From day 7, the cells were cultured in RPMI/B27 with insulin. After day 17 of differentiation, the CM cells were maintained in glucose-free iCell medium (CDI, Madison, WI) containing 1 mM pyruvate and 4 mM glutamine. All other media, materials, and reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific/Invitrogen unless specified. Under these optimized conditions, >90% purity (flow cytometry analysis) was achieved on day 30 (Fig. 1E).

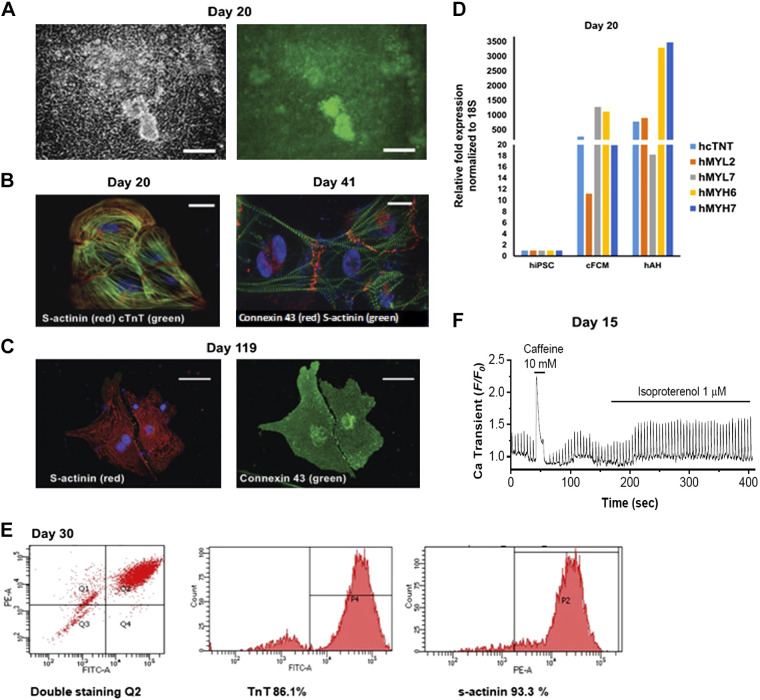

Figure 1.

Analysis of cardiac fibroblast-derived hiPSC-CMs (cFCM). A: differentiated cFCMs expressing αMHC-eGFP at day 20 of differentiation. Bright-field (left), GFP (right), scale bar = 100 μm. B: immunofluorescence staining of cTnT2, and cardiac S-actinin at day 20 and connexin-43 and S-actinin at day 41 of differentiation. Scale bar = 50 μm. C: immunofluorescence staining of S-actinin and Cx43 at day 119 of differentiation. Scale bar = 50 μm. D: relative fold change in the expression of cardiac markers in cFCM and human adult heart (hAH) compared with hiPSCs. 18S was used as a housekeeping control for normalization. E: flow cytometry analysis of cFCMs by cTnT and S-actinin double labeling (left). Percentage of the cTnT-2-positive cFCMs at day 30 of differentiation (middle). Percentage of the S-actinin-positive cFCMs at day 30 of differentiation (right). n = 3 experiments. F: calcium transient measurements in cFCMs at day 15 using fluo-4 as fluorescent dye to visualize spontaneous beating and pacing in cFCMs. T50 = 300 ms; caffeine stimulation (10 mM), followed by isoproterenol stimulation (1 μM). Cx43, connexin-43; cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; hAH, human adult heart.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The presence of cardiac markers was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and converted into cDNA using the TaqMan RT Kit (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR machine. Primers for hcTnT-2 and contractile markers, including human myosin light chains hMYL2, hMYL7, and hMYH7, were purchased from IDT. Relative expression levels were compared with those obtained using mRNA from human hearts (Ambion). Expression of markers was normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. Forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sequences are the following: hcTnT-2: F-TTCACCAAAGATCTGCTCCTCGCT and R-TTATTACTGGTGTGGAGTGGGTGTGG; hMYH7: F-TCGTGCCTGATGACAAACAGGAGT and R-ATACTCGGTCTCGGCAGTGACTTT; hMYL2: F-TGTCCCTACCTTGTCTGTTAGCCA and R-ATTGGAACATGGCCTCTGGATGGA; hMYL7: F-ACATCATCACCCATGGAGACGAGA and R-GCAACAGAGTTTATTGAGGTGCCC; and PPARα: F-ATTACGGAGTCCACGCGTGTG and R-TTGTCATACACCAGCTTGAGT.

Immunofluorescence Staining

hiPSCs were cultured on Matrigel-coated coverslips in mTeSR1 for 2 days. Immunofluorescent staining using OCT3/4 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), hNanog (1:200, R&D systems), and Alexa Fluor-488 antihuman TRA-1–60-R (1:50, BioLegend) antibodies was performed on undifferentiated hiPSCs (Supplemental Fig. S1). Standard immunofluorescence staining was performed to confirm the expression and distribution of CM markers using antibodies reactive with cardiac troponin T (hcTNT-2, 1:50, Abcam), S-actinin (Sigma/A7811/Clone: 1:500, EA-53), and connexin-43 (1:200, Sigma). The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG/A-11008 (1:400, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG2b/A-21145 (1:400, Invitrogen).

Confocal Microscopy

Human iPSCs cultured on Matrigel-coated glass-bottom chambers (Maltek) were stained by indirect immunofluorescence and subjected to confocal imaging using a Nikon A1RSI confocal microscope equipped with a ×20 Plan Apo VC objective lens. The confocal images were analyzed using Nikon NIS elements software.

Flow Cytometry

To determine the purity of hiPSC-CMs, flow cytometry was performed as described (39). On day 20 and postdifferentiation, the cells were washed with PBS, treated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technology), and dissociated. After the cells were counted with a hemocytometer, the cells were centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min, and the pellet was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed cells were treated with 1 mL of 90% cold methanol. The cells were washed with FlowBuffer-1 (0.5% BSA in PBS), resuspended in 100 μL of FlowBuffer-2 (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% BSA in PBS) with a 1:400 dilution of hcTnT-2 primary antibody (Abcam), and incubated overnight at 4°C. After being washed with FlowBuffer-2, cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, followed by serial washes with FlowBuffer-2. The cell pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of FlowBuffer-1, transferred into flow round-bottom tubes, and placed on ice for the flow cytometric analysis with a FACS Calibur. The FL1 channel was utilized to analyze GFP/FITC signal.

Measurement of Ca2+ Transients

Cells were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM (5 μM for 40 min). Ca2+ fluorescence (EX/EM: 485/530 nm) was monitored using a Nikon Eclipse TE200 inverted microscope and recorded using an Ixon Charge-Coupled Device camera (Andor Technology) operating at ∼50 fps, as described in our previous studies (84, 85). The fluorescence intensity was measured as the ratio of fluorescence (F) over basal diastolic fluorescence (F0).

Mitochondrial Isolation

Mitochondria were isolated from cFCMs on days 12, 40, and 116 of differentiation, from dFCMs on days 12, 39, and 105 of differentiation, and from neonatal (1 day) and adult (90 days) mouse hearts using mitochondrial isolation kits for cultured cells or tissue (Thermo Fisher, No. 89874 and No. 89801, respectively) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Proteomics Analysis

Isolated mitochondria were analyzed from 1) cFCMs at days 12, 40, and 115; 2) dFCMs at days 12, 39, and 105; and 3) hearts of neonatal (1 day) and adult (90 days) mice. Proteins were extracted using lysis buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 4% (wt/vol) SDS, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Fifteen micrograms of proteins from each sample was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE separation, and the entire gel lane of each sample was excised into ∼1-mm cubes for in-gel trypsin digestion. The proteins were reduced with 5 mM DTT and alkylated with 25 mM iodoacetamide. Trypsin (Promega, Cat. No. V511A) was added in a ratio of 1:50 (trypsin:protein) and incubated overnight at 37°C. The resulting peptides were desalted with a C18 spin column (The Nest Group, Inc.) and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a U3000 Ultimate nano LC system coupled with Q Exactive MS instrument (Thermo Scientific). In brief, the peptides were separated on a C18 reversed-phase nanocolumn (Acclaim Pep RSLC 75 μm × 50 cm, 2 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific) with a 185 min of gradient (Solvent A is 2% acetonitrile (ACN) in 0.1% FA, and Solvent B is 85% ACN in 0.1% FA). The eluent peptides were directly introduced to mass spectrometry via Nanospray Flex ion source. The spray voltage was 2.15 kV in positive mode. The temperature of ion transfer tube was 275°C. The full MS spectra were acquired in the mass range of m/z 350–1,700 with the resolution of 70,000 full-width at half maximum (FWHM) and automatic gain control (AGC) of 1E6. Fifteen most intensive ions with charge state between 2 and 5 were subjected to MS/MS analysis with the dynamic exclusion of 60 s. Normalized collision energy (NCE) was set to 27, and the resolution for MS/MS analysis was 17,500 FWHM. Isolation window was set to 2 m/z, and maximum injection time for both MS1 and MS2 was 100 ms.

For data analysis, the MS/MS spectra were searched against a SwissProt human database (20,292 sequences) using a local MASCOT (V.2.4) search engine on the Proteome Discoverer (V1.4, PD) platform. The MS tolerance was 10 ppm, and fragment tolerance was 0.1 Da. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set to fixed modification, whereas oxidation of methionine and acetylation of NH2-terminus of protein were set to variable modification. Maximum missed cleavage of trypsin was 2. The protein false discovery rate was less than 1%. Scaffold software was used for the comparison of identified proteins and their relative quantitation using .msf files from PD. For the proteins that showed in some samples, but not in the others, the missing value was replaced by 0 counts. To avoid 0 counts as a denominator or exaggerating the ratio from the small spectra counts, we arbitrarily add 2 in each spectra count before calculating the relative quantitation of the proteins based on spectra counting method. LC-MS/MS identified between 2,041 and 2,690 proteins from the different samples analyzed; 926 of these were identified as mitochondrial proteins based on the gene ontology annotations in Scaffold software (v 4.6, Proteome Software, Portland, OR). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository (50) with the data set identifier PXD014317.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

The mitochondrial proteins assigned by Scaffold Proteome Software were imported into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (QIAGEN, Inc.). IPA was performed on mitochondrial proteins that were twofold differentially expressed in cFCMs at days 40 and 115 versus day 12, in dFCMs at days 39 and 105 versus day 12, and in mouse adult heart (3 mo) versus neonatal heart (1 day) (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8139359.v2). Canonical pathways, upstream regulators, and molecular networks were identified based on the ingenuity knowledge base and the ingenuity collection of experimentally observed data. IPA also predicted canonical pathways and upstream regulators as activated or inhibited based on a positive or negative z-score, respectively.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell protein extracts from cFCMs and dFCMs at days 35, 75, and 118 of iPSC-CM differentiation were prepared by solubilizing the cells using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher) using BSA as a standard. A total of 10–20 µg of protein per sample was resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane with 0.45-µm pores (Millipore) and probed with antibodies recognizing NDUFB8 (Abcam, H4664), SDHB, MTCO1 and ATP5A (Abcam, H4664 antibody cocktail), LonP1 (Sigma, B96441), Cpt1 (Abcam 134988), Parkin (Cell Signaling, 2132S), and Hsp90 (Cell Signaling 4874S). Immunoblots were imaged following chemiluminescent detection using ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare).

Seahorse Metabolic Assay

To determine the glucose versus fatty acid utilization, differentiated cFCMs were cultured in a 96-well Seahorse plate (7 × 104 to 1.1 × 105 cells per well) and analyzed using an XF-96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse, Agilent). The cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with B27 until days 17–20, after which the cells were cultured in iCell medium (FUJIFILM Cellular Dynamics, Madison, WI, Cat. No. M1003) containing 10% serum. One hour before the assay, the medium was replaced with serum-free XF assay medium (modified DMEM without bicarbonate, glucose, pyruvate, or glutamine) (Seahorse Bioscience), which was supplemented with 2 g/L glucose as per the manufacturer’s protocol, and it was confirmed that the differentiated cFCMs were still beating. Using serum-free medium allowed us to evaluate the endogenous fatty acid oxidation (FAO) that occurs during differentiation and maturation of cFCMs, specifically, to compare the FAO between two different durations of cFCMs in culture (75 vs. 105 days), and to avoid the influence of any exogenous supplemental fatty acid source on the FAO assay. To determine the contribution of endogenous FAO to the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of cFCMs, we used etomoxir (ETO, 200 or 250 µM) (Sigma-Aldrich), which is a specific inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (Cpt1). To determine the contribution of glucose to the OCR, the cells were also treated with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG, 50 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich), which blocks glycolysis. Results were obtained as picomoles O2 consumption per minute. The results were normalized to the baseline and reported as a percent OCR relative to baseline.

Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Assay to Determine the Effect of LonP1 on FAO

Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer was used to determine the effect of LonP1 knockdown on FAO as measured by OCR. For LonP1 knockdown experiments, we chose to employ neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (nRVMs) rather than cFCMs because LonP1 deletion is embryonic lethal during gastrulation in mice (57) and downregulation induces cell death or inhibits cell proliferation in B-cell lymphoma, HeLa, melanoma, and lung fibroblast cells (5, 7, 47, 57). nRVMs, however, survive upon LonP1 downregulation (74). In addition, optimization of shRNA-mediated downregulation of LonP1 in cFCMs in terms of dosages and timing, and Seahorse experiments would require a large number of cFCMs and this was technically challenging. OCR was measured in the presence and absence of etomoxir—an inhibitor of Cpt1, which is essential for FAO that is located at the inner face of the outer mitochondrial membrane. 5 × 104 nRVMs per well were seeded in 16 replicates of a XF96 plate (n = 2 experiments). After 24 h, nRVMs were transduced with control or LonP1 shRNA adenoviral particles multiplicity of infection 10 (MOI 10) as previously described (74). On day 5 posttransduction, the growth medium was replaced with substrate limited medium—DMEM (Corning no. 17–207-CV) supplemented with 0.5 mM glucose, 1 mM glutamine, 0.5 mM carnitine, and 1% FBS, and maintained overnight at 37°C as per manufacturer’s FAO assay protocol (Seahorse, Agilent). On the following day, 45 min before the assay, the culture medium was replaced with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) (110 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM Na2HPO4) supplemented with 2.5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM carnitine, and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and incubated in a non-CO2 incubator. Mito Stress Test was used as described (74) in the presence of etomoxir (40 µM) and palmitate-BSA (100 µM), each of which was added at 15 and 0 min before the assay, respectively. FAO was determined by calculating the difference in the OCR value between the nRVMs treated with and without etomoxir. OCR values were expressed as picomole per minute per microgram of protein.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests for two or more groups and Student’s t test for two groups using GraphPad InStat software. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of hiPSC-CMs

hiPSCs were reprogrammed from human cardiac fibroblasts (cFs) using Sendai virus expressing the Yamanaka factors (Invitrogen) (Supplemental Fig. S1). These cells expressed a GFP reporter gene under the control of the Myh6 cardiac promoter (32) (Fig. 1A, Supplemental Fig. S2A). To differentiate hiPSCs into CMs, we used an optimized GiWi (GSK inhibitor and Wnt inhibitor) protocol, in which ROCK inhibitor was used to ensure optimal attachment (39). The protocol was further optimized by adding Matrigel overlay (82) on days 0 and 3 of differentiation at the time of GSK and Wnt inhibition. From day 7 of hiPSC-CM differentiation, the medium containing insulin was changed every other day until the cells started beating at day 12 ± 2 of differentiation, after which the medium was changed daily. Similar results were obtained using three sources of human PSCs—hiPSCs derived from cardiac fibroblasts (cFCM, Fig. 1B), hiPSCs derived from dermal fibroblasts (dFCM, Supplemental Fig. S2), and hESCs.

Molecular characterization was performed on hiPSC-CMs from day 12 of differentiation and onward. We analyzed 1) expression of cardiac markers, 2) purity of hiPSC-CMs, and 3) calcium transients and beating. At day 20, beating hiPSC-CMs exhibited mRNA expression of cardiac and contractile markers hMYL2, hMYL7, hMYH7, and TnT (Fig. 1D), which was consistent with the presence of sarcomeric organization, as shown by immunostaining for cardiac troponin T (hcTnT2), S-actinin, and connexin 43 (Cx43) (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. S2B, top). Sarcomeric organization (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. S2B, bottom) and cardiac beating (Supplemental Video S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13118354) were also apparent at time points >90 days. The purity of differentiated cFCM cells ranged from 86.1% to 93.3% at day 30, as determined by flow cytometry analysis using cTnT and cardiac S-actinin labeling, respectively (Fig. 1E). On days 15 and 30, beating hiPSC-CMs displayed spontaneous and paced calcium transients, which responded to isoproterenol and caffeine (Fig. 1F, Supplemental Fig. S2C).

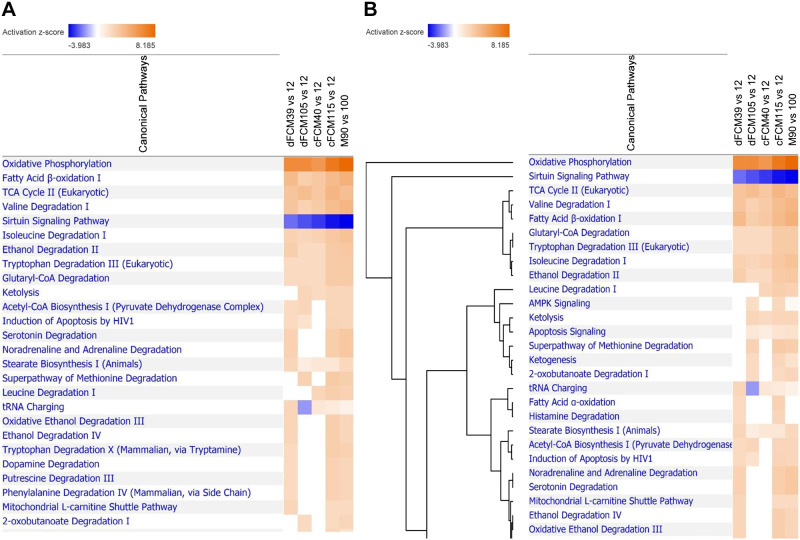

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis Prediction of Canonical Pathways Involved in Cardiac Differentiation/Maturation

The developmental pathways underlying mitochondrial biogenesis during CM maturation are not fully understood (13, 23, 55). To gain further insight, proteomic analysis was performed using mitochondria isolated from cFCMs differentiated for 12, 40, and 115 days, from dFCMs differentiated for 12, 39, and 105 days, and from neonatal (1 day) and adult (90 days) mouse hearts. Mitochondrial-enriched protein fractions from each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE, the entire lane of the gel was subject to in-gel trypsin digestion, and the resultant peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described in the materials and methods. The relative quantification of proteins on day 39/40 versus day 12, day 105/115 versus day 12, and adult versus neonatal was calculated based on the spectral counting method. Scaffold software analysis identified 926 mitochondrial proteins based on gene ontology annotations (65).

IPA was used on the mitochondrial proteomics data sets obtained from human cFCMs and dFCMs at the different time points of differentiation, and on those from mouse adult hearts (90 days) versus neonate hearts (1 day). IPA uses algorithms in tandem with its extensive compendium of literature-based knowledge and massive database of gene expression measurements to predict up- and downregulation of top canonical pathways, upstream regulators, and downstream effects. The general trends in the major mitochondria-associated signaling processes and pathways determined from our proteomic analysis are shown in Fig. 2. IPA showed significant upregulation of pathways associated with mitochondrial energy metabolism at later time points of differentiation in hiPSC-CMs (dFCM days 39 and 105, and cFCM days 40 and 115), and in the adult mouse heart (3 mo) (Fig. 2A). The most highly upregulated pathways (Fig. 2A) were those mediating FAO, OXPHOS, and the TCA cycle, which are crucial for meeting the increased energy demand during cardiomyogenesis (13, 55). In addition, IPA showed that pathways involved in catabolism of branched chain amino acids (BCAA) were among the top significantly upregulated pathways observed in dFCMs at days 39 and 105 versus day 12 and in cFCMs at days 40 and 115 versus day 12, as well as in the adult versus neonatal mouse heart (Fig. 2A). Valine and isoleucine catabolism are key in the anaplerotic generation of succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, respectively, which fuel the TCA cycle (17). The majority of upregulated mitochondrial proteins observed in these highly activated canonical pathways of OXPHOS, TCA, FAO, valine, and isoleucine degradation were consistent with the IPA knowledge (i.e., literature) base and resulted in significant positive z-scores (Supplemental Figs. S3–S7, respectively) In addition, the hierarchical cluster analyses using IPA showed that these top observed canonical pathways were closely interconnected, suggesting that these pathways function in parallel, contributing to reprogramming energy metabolism during cardiac differentiation/maturation (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Canonical mitochondrial pathways predicted by IPA. A: heat map of top canonical pathways generated by IPA of mitochondrial proteomics in dFCM days 39 and 105 versus day 12, cFCM days 40 and 115 versus day 12; and mouse adult heart (90 days) versus neonatal heart (1 day). Orange color indicates that the pathway has a positive activation z-score; blue color shows that the pathway has a negative z-score. B: hierarchical cluster analysis of the canonical pathways by IPA. The analysis shows that the top regulated canonical pathways are closely related. Only mitochondrial proteins with differential greater than twofold changes were included in the IPA. cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; dFCM, dermal fibroblasts; IPA, ingenuity pathway analysis.

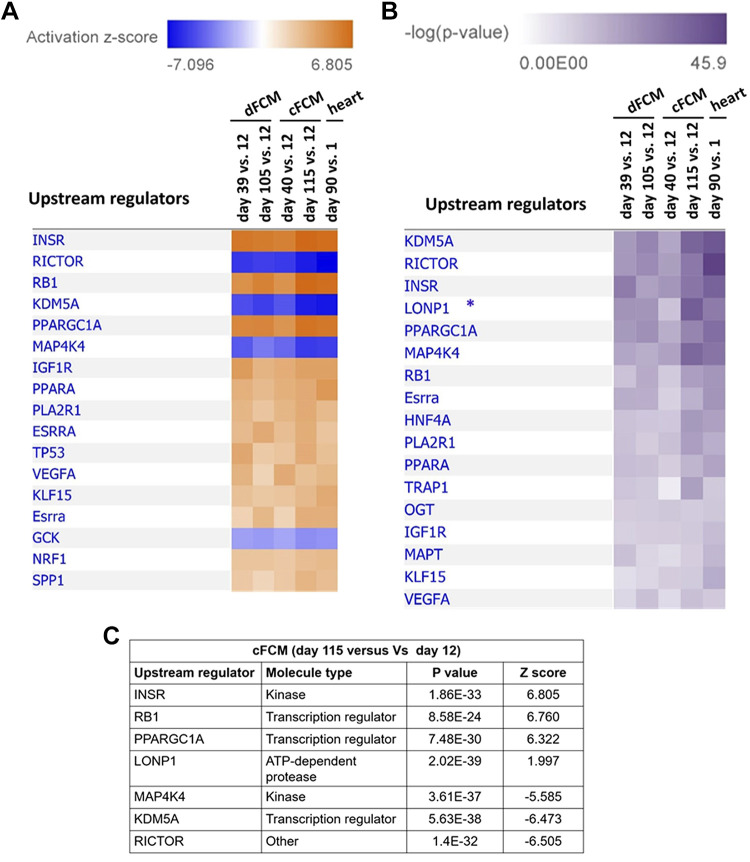

IPA Prediction of Upstream Regulators in Cardiac Differentiation/Maturation

IPA also predicted the activation or inactivation of key upstream regulators in our data sets comparing dFCM at days 39 and 105 versus 12 days, cFCM 40 days and 115 days versus 12 days, and in adult versus neonatal mouse hearts (Fig. 3). Activation scores (z-score, Fig. 3A) and the significance of predicted activation (P value, Fig. 3B) of the upstream regulators were determined. For all groups that we analyzed, the top upstream regulators predicted by IPA were INSR, insulin receptor; RICTOR, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin); RB1, retinoblastoma (RB) transcriptional corepressor 1; KDM5A, lysine demethylase 5A; PPARGC1A, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α (PGC-1α), and MAP4K4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4 (Fig. 3A). The top regulators predicted to be significantly activated, showing a positive z-score, were INSR, RB1, and PPARGC1A. By contrast, the top regulators predicted to be significantly inactivated, showing a negative z-score, were RICTOR, MAP4K4, and KDM5. RB1, PPARGC1A, and KDM5 are transcriptional regulators, whereas INSR and MAP4K4 are kinases. A regulator of BCAA catabolism, Krüppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) (19, 24, 67, 83), was also identified as an upstream regulator during cardiac differentiation/maturation (Fig. 3, B and C). IPA analysis also identified the mitochondrial LonP1 protease as one of the top upstream regulators, which was predicted based on the high level of significance (i.e., low P value) (Fig. 3, B and C). However, no significant z-score indicating activation or inhibition was obtained by IPA for LonP1 because of an insufficient knowledge base about this protein. LonP1 is a major mitochondrial ATP-dependent protease that regulates mitochondrial metabolism, energetics, and proteostasis (48, 57, 73, 74). Based on our IPA analysis, the molecules that are known to interact with these upstream regulators are shown in Supplemental Fig. S8.

Figure 3.

IPA of upstream regulators. A: top upstream regulators based on IPA-predicted activation z-scores. B: top upstream regulators based on P values. IPA showed that LonP1 (*) had a strong P value; however, no z-score was assigned because of an insufficient knowledge base about this protein. C: summary of top upstream regulators in cFCMs at day 115 versus day 12 as a representative group, and their corresponding z-scores and P values. cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; IPA, ingenuity pathway analysis.

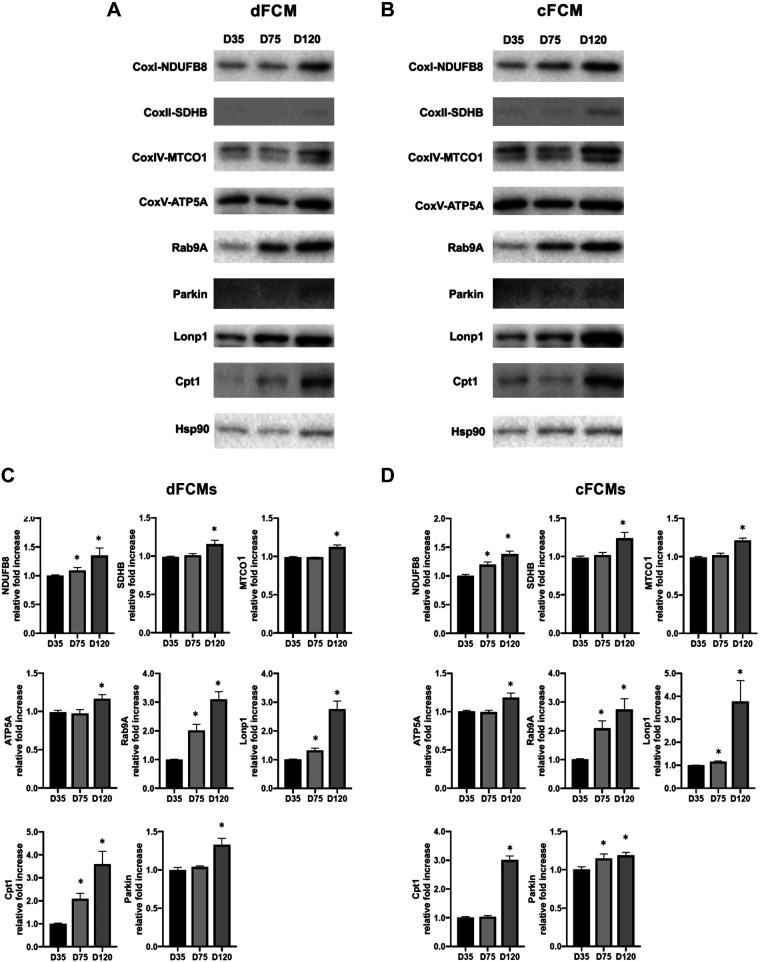

Validation by Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts from dFCMs (Fig. 4A) and cFCMs (Fig. 4B) was performed to confirm the upregulation of proteins identified by proteomic analysis and by IPA. We examined OXPHOS complex subunits—Complex I, NDUFB8; Complex II, SDHB; Complex IV, MTCO1; Complex V, ATPA; mediators of mitophagy, Parkin and Rab9A (61); the mitochondrial ATP-dependent LonP1 protease; and Cpt1, the rate-limiting enzyme in β-oxidation of fatty acids (27). Samples were collected at days 35, 75, and 120 of iPSC-CM culture. At 75 and/or 120 days of differentiation, we observed significant upregulation of NDUFB8, SDHB, MTCO1, ATPA, Parkin, Rab9, as well as LonP1 and Cpt1. Quantification of the immunoblot data is provided in Fig. 4, C and D.

Figure 4.

Upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Immunoblot of whole cell lysates from dFCMs (A) and cFCMs (B) for mitochondrial proteins shown to be upregulated in these iPSC-CMS over the time course of 35, 75, and 120 days. Subunits of OXPHOS Complex I, NDUFB8; Complex II, SDHB; Complex IV, MTCO1; and Complex V, ATPA, are shown. Proteins mediating mitophagy, Rab9A and Parkin, the mitochondrial LonP1 protease, and carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1), which mediates the rate-limiting step in FAO are shown. C and D: densitometric analysis of immunoblots showing the relative fold differences in intensity in dFCMs (C) and cFCMs (D) at days 35, 75, and 120 of differentiation. Bands were normalized to Hsp90 and then compared with day 35 (n = 3 experiments). Data values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 is considered as significant compared with day 35 by one-way ANOVA. cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; dFCM, dermal fibroblasts; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation.

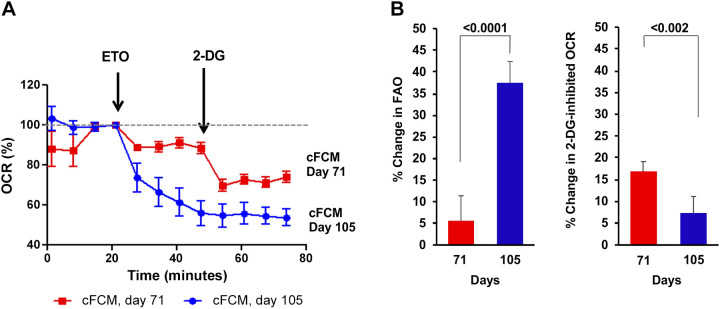

Metabolic Shift to Fatty Acid Oxidation Over Time in Differentiated cFCMs

Next, we examined mitochondrial energy metabolism in iPSC-CMs on different days of differentiation by measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Etomoxir (ETO), which specifically inhibits fatty acid oxidation (FAO) by irreversibly blocking Cpt1, was used to determine the contribution of FAO to the OCR in cFCMs. To determine the contribution of glucose metabolism to the OCR, 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) was used, which blocks glycolysis by inhibiting glucose-6-phosphate isomerase competitively and hexokinase noncompetitively (30, 78). The effect of ETO (200 µM) on OCR was examined in cFCMs at days 71 and 105 (Fig. 5). At day 71, ETO reduced OCR by ∼6% relative to baseline, and this reduction remained stable over the 20-min interval until the addition of 2-DG, which reduced OCR further by ∼17%. By contrast, at day 105, ETO progressively reduced OCR by an average of ∼37% relative to baseline throughout the 20-min time interval, after which only a negligible reduction in OCR was observed upon the addition of 2-DG. These data show that, in cFCMs, the contribution of FAO to OCR was significantly greater (∼30%) at day 105 than at day 71 (∼6%) (Fig. 5B, left). In addition, glucose contributes significantly less to OCR (∼5%) at day 105 than at day 71 (∼15%) in these cFCMs (Fig. 5B, right). Together, these results show that cFCMs at day 105 use fatty acids as the principal substrate for energy production, as more commonly observed in the adult heart, suggesting that mitochondrial metabolism in cFCMs shifts toward fatty acid utilization during this period of differentiation.

Fig. 5.

Upregulation of fatty acid oxidation. A: change in oxygen consumption rate (% OCR) in cFCMs at days 71 and 105 of differentiation. ETO (200 µM) was used to inhibit FAO, and 2-DG (50 mM) to inhibit glycolysis. A representative profile is shown of experiments performed at days 71 or 72 (n = 3 experiments), and at day 105 (n = 2 experiments) using ETO (200 or 250 µM) and 2-DG (50 mM). The dotted line indicates baseline OCR. B: percent change in OCR by FAO inhibition and percent change in OCR by 2-DG inhibition based on the experiment shown in (A). Unpaired two-tailed t test was used to determine significance (P value). cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; ETO, etomoxir; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; OCR, oxygen consumption rate; 2-DG, 2-deoxy-d-glucose.

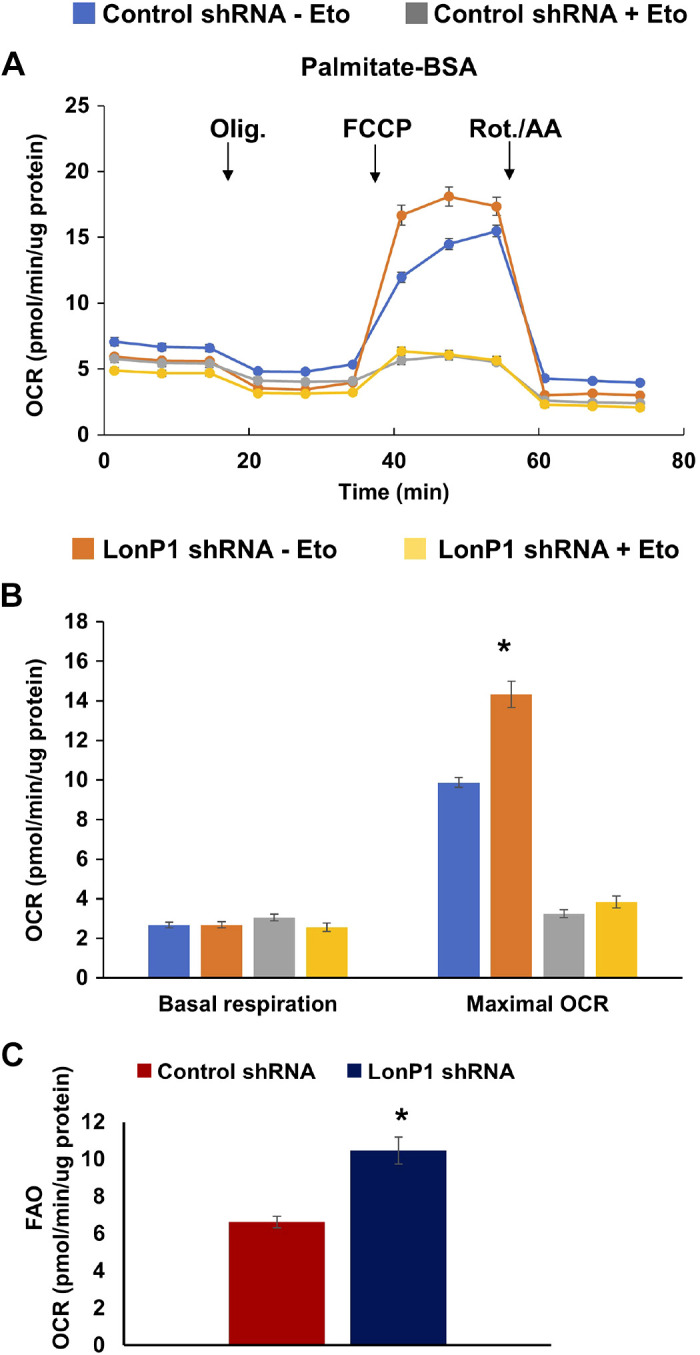

LonP1 Knockdown Increases Fatty Acid Oxidation in Neonatal Rat Ventricular Myocytes

As mitochondrial LonP1 was increasingly upregulated in cFCMs and functions as a master regulator of mitochondrial proteostasis, energetics, and metabolism (6, 53, 56, 57, 75), we investigated whether it plays a role in FAO in neonatal cardiac myocytes. For these experiments, we used nRVMs because these cells, like cFCMs, exhibit glycolysis and FAO. An adenoviral delivery system was used to transduce nRVMs with control or LONP1 targeted shRNAs. Four days posttransduction, real-time OCR was measured in cells incubated in medium supplemented with the fatty acid palmitate conjugated to BSA (palmitate-BSA, 100 µM). We observed a significant increase in OCR in LonP1 knockdown nRVMs as compared with control cells incubated with palmitate-BSA (Fig. 6, A and B). Increased mitochondrial respiration in LonP1 knockdown nRVMs when cultured with palmitate-BSA was blocked by the FAO inhibitor etomoxir (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, FAO was found to be significantly increased in the presence of LonP1 downregulation (Fig. 6C). These findings suggested that the downregulation of LonP1 upregulates FAO. This is in contrast to control and LonP1 knockdown nRVMs cultured in low-glucose medium containing BSA without palmitate (Supplemental Fig. S9C), in which OCR was only nominally inhibited by etomoxir presumably as a result of endogenous FAO (Supplemental Fig. S9D). These results suggest that LonP1 serves as a negative feedback mechanism of FAO during the metabolic maturation of iPSC-CMs.

Figure 6.

Effect of LonP1 knockdown on FAO. A: measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in isolated nRVMs, subjected to mito stress test after supplementing with palmitate-BSA (100 µM) as a source of fatty acid in the presence (+) or absence (−) of etomoxir (40 µM), an inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation. B: comparison of basal and maximal respiration (OCR) between control and LonP1shRNA groups in the presence or absence of etomoxir treatment. C: FAO was measured as the difference in OCR with and without etomoxir treatment, in the presence of palmitate (see Supplemental Fig. S9, D and C, for BSA control). Data values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t test. FAO, fatty acid oxidation; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

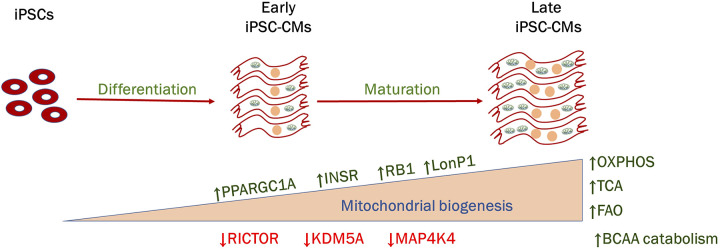

DISCUSSION

In this study, we undertook a proteomics analysis of mitochondria isolated from iPSCs reprogrammed from cardiac and dermal fibroblasts, which were differentiated into CMs and cultured for 12 to 115 days (Fig. 7). As controls, this analysis also included mitochondria isolated from hearts of neonatal and adult mice (1 day and 90 days old, respectively). Mitochondria from adult mouse heart CMs showed high levels of proteins mediating FAO as compared with neonatal mouse heart CMs. The energy metabolism of early hiPSC-CMs is thought to be similar to that of embryonic/neonatal CMs (59). Longer time periods of differentiation, from 12 days to ∼40 and ∼115 days, in both cFCMs and dFCMs showed a metabolic upregulation of FAO (Figs. 4 and 5 and Supplemental Table S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13118429). We also observed an increase in the levels of OXPHOS protein subunits in mitochondria from dFCMs and cFCMs from day 12 of differentiation to day 39/40 and day 105/115 (Fig. 4), which was consistent with the increased levels of these subunits in mitochondria from adult mice versus neonatal mice (Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 7.

Regulators of mitochondrial and metabolic maturation of iPSC-CMs identified by proteomics and IPA. Human iPSCs from cardiac and dermal fibroblasts were differentiated into cardiac myocytes (cFCMs and dFCMs, respectively). On day 0, the cells were treated with inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) and Wnt signaling. From days 7 to 9, cells were cultured with insulin. After day 17, cells were maintained in glucose-free iCell medium with pyruvate and glutamine. During a time course of differentiation at days 12–115, LC-MS/MS of enriched mitochondrial proteins combined with IPA predicted the activation of OXPHOS, TCA cycle, FAO, and BCAA catabolic pathways. IPA predicted the activation of the genes/proteins, PPARGC1A, INSR, RB1, and LONP1, and the downregulation of RICTOR, KDM5, and MAP4K4. cFCM, cardiac fibroblasts; dFCM, dermal fibroblasts; IPA, ingenuity pathway analysis; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cell.

IPA also predicted an increase in the pathways for valine and isoleucine degradation during cardiac differentiation/maturation. Our proteomics data and IPA clearly suggest that BCAA catabolism is upregulated during iPSC-CMs differentiation/maturation. Most of the enzymes that catabolize the BCAAs valine and isoleucine are upregulated many folds during CM differentiation/maturation (Supplemental Figs. S6 and S7, respectively). These enzymes include BCAA transaminase, 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase, 2-methylacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, enoyl-CoA hydratase, 3-hydroxy isobutyryl-CoA hydrolase, and 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase. BCAA catabolism yields NADH and FADH2, which are used for ATP generation. In addition, the final products of BCAA catabolism, acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA, fuel the TCA cycle and can be fully oxidized, ultimately leading to ATP generation, consistent with energy demand during cardiac maturation. Defective amino acid metabolism has been observed in hypertrophied or myocardial infarcted mouse hearts (36, 62). Defective BCAA catabolism and accumulation of its intermediates have been reported in both mouse and human failing hearts (67). Studies have identified KLF15 as a key transcription factor that promotes BCAA catabolism in the heart (19, 24, 83). Another study showed that KLF15 is a top upstream regulator of BCAA catabolism in the heart (67). Consistent with these studies, our IPA performed in this study also showed that KLF15 is an upstream regulator and was significantly activated during the differentiation/maturation of iPSC-CMs in all groups analyzed (Fig. 2, A and B).

During the differentiation and maturation of dFCMs and cFCMs from day 12 to 39/40 and 105/115, IPA predicted the activation of several other upstream regulators and their respective pathways (Fig. 7). Unsurprisingly, PGC-1α (encoded by the PPARGC1A gene) was identified as a major upstream regulator that is activated, as demonstrated by a positive z-score, which is considered significant when >2 or <−2 (Fig. 3). The significance of this analysis is shown by the P value; smaller P values indicate that the predicted association is less likely to be random. PGC-1α is a transcriptional co-activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), which is a master regulator of glucose and fatty acid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis (76). The PPAR pathway has been shown to be progressively enriched throughout the maturation of CMs (43). The predicted activation of PGC-1α in our IPA analysis lends credence to the other upstream regulators that are predicted to be activated, namely the insulin receptor (IR) encoded by the INSR gene and retinoblastoma protein (Rb1) encoded by the RB1 gene (Fig. 3C). Previous work has shown that insulin stimulates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which is the central gatekeeper at the control point between glycolysis and the TCA cycle. PDH regulates the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, which fuels the TCA cycle and the generation of ATP by OXPHOS (10, 20, 40, 58, 80). Studies suggest that insulin upregulates PDH activity in skeletal muscle, liver cells, and adipose tissue by stimulating the phosphorylation of PDH phosphatase (PDP), which increases phosphatase activity (10, 80). The upregulation of PDP maintains PDH in its active dephosphorylated state. During the development of CMs, it is possible that activation of IR signaling initiates downstream PI3K-Akt signaling events, which, along with glucose influx, promote the metabolic switch toward increased reliance on OXPHOS. Further studies are required to explore the impact of the IR signaling pathway on mitochondrial biogenesis during CM differentiation and maturation.

IPA predicted Rb1 to be another activated upstream regulator (Fig. 3). Rb1 is best known as a tumor suppressor and transcriptional repressor that inhibits the cell cycle (18). Its deficiency or dysfunction has been identified in several major cancers (12). Recent work showed that Rb1 also plays a role in mitochondrial metabolism and energetics by inducing metabolic flux into the OXPHOS pathway (46, 68). Proteomic analysis of tissue-specific RB1 knockout in mouse colon or lung showed a striking decrease in mitochondrial proteins belonging to the respiratory chain and OXPHOS (26). Decreases in mitochondrial mass and in mitochondrial DNA content relative to nuclear DNA were also observed (26). In vivo [13C] glucose analysis, oxygen consumption, and immunoblotting experiments demonstrated that Rb1 deficiency negatively affected both TCA cycle kinetics and OXPHOS energetics (26). Causative involvement of Rb1 in metabolic maturation of hiPSC-derived CM remains to be clarified.

IPA also identified several inactivated upstream regulators with strong z-scores and P values, KDM5A, Rictor, and MAP4K4 (Fig. 3C). KDM5A (lysine [K]-specific demethylase 5A) is a histone demethylase that demethylates histone H3 on Lys4 (H3K4). KDM5A has been shown to interact with Rb1 (4, 16, 33). Experiments have shown that KDM5A (also called RBP2) is recruited to the promoter region of key mitochondrial genes resulting in demethylation of H3K4 in the promoter and transcriptional repression (44). KDM5A has also been shown to counteract the role of Rb in promoting differentiation (72), and loss of KDM5A in RB1 knockout mice restores differentiation through increased mitochondrial respiration (44). Evidence has shown that KDM5A directly regulates genes encoding mitochondrial proteins and that, during differentiation, a decrease in KDM5A binding activates the expression of these genes (44).

Little is known about the role of mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) and its essential subunit Rictor in the modulation of mitochondrial metabolism and energetics. However, previous work has shown that the knockdown of Rictor in Jurkat cells increased mitochondrial respiration and oxidative capacity (64). This change was not associated with alterations in mitochondrial mass or mitochondrial membrane potential (64). Consistent with this, microarray studies performed in mice with liver-specific knockdown of Rictor showed an upregulation of genes encoding components of OXPHOS (37). There is also limited knowledge about the role of the serine/threonine protein kinase MAP4K4 in mitochondrial biogenesis. However, MAP4K4 is emerging as a signaling node in metabolic diseases (77). RNA interference-mediated depletion of MAP4K4 in early differentiation or in fully differentiated adipocytes upregulates GLUT4, which is the insulin-regulated glucose transporter (69).

Another observation demonstrated by our combined proteomics data, immunoblotting, and IPA is the significant upregulation of mitochondria LonP1 during the differentiation of dFCMs and cFCMs, as well as in adult versus neonatal hearts (Figs. 3 and 4). LonP1 is a major mitochondrial ATP-dependent protease, functioning in mitochondrial proteostasis, bioenergetics, and metabolism (48, 66, 73, 74). We showed that LonP1 was upregulated in dFCMs and cFCMs at days 35, 75, and 105 and of differentiation as compared with day 12 (Fig. 4, Supplemental Table S1). Interestingly, oxygen consumption rate analysis showed that LonP1 knockdown upregulated FAO in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes (nRVMs) when palmitate-BSA was supplemented in low-glucose culture medium (Fig. 6). Upregulation of FAO in the LonP1 knockdown cells was inhibited by etomoxir, demonstrating that the increased mitochondrial respiration in the presence of palmitate-BSA was attributable to palmitate oxidation within mitochondria. Although immature neonatal rat heart cells have been shown to generate energy principally by glycolysis, these nRVMs are nevertheless capable of oxidizing exogenous palmitate-BSA when cultured in low-glucose medium (Fig. 6A). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that LonP1 upregulation during iPSC-CM differentiation contributes to a negative feedback mechanism for fine-tuning FAO during the transition from glycolysis to FAO as immature cardiac myocytes differentiate and mature. We did not evaluate the effect of LonP1 downregulation upon mitochondrial respiration in cFCMs for the aforementioned reasons, including technical issues. The specific role of endogenous LonP1 during metabolic maturation of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes remains to be tested.

Although we show that LonP1 negatively regulates FAO, other potential roles of LonP1 in cardiac differentiation and maturation must also be considered. During development, LonP1 maintains the integrity and expression of mitochondrial DNA (11, 22, 41, 57), regulates mitochondrial proteostasis by degrading abnormal and damaged proteins, prevents protein aggregation (73, 75), and regulates glucose oxidation (48). In addition, LonP1 downregulation inhibits cell proliferation and promotes cell death (5, 7, 42, 57, 76). LonP1 is induced by ROS (51, 52), in turn playing an essential role in mediating development, physiology, and differentiation (1, 38).

Our recent work investigating a profound neurological disorder caused by the bi-allelic mutation in human LONP1 c.2282 C > T (p.Pro761Leu) has shown that wild-type LonP1 is required for regulating the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which is a key enzyme at the axis of glucose and fatty acid oxidation (47, 48). In primary fibroblasts expressing dysfunctional LonP1-Pro761Leu, we demonstrated that PDH activity is blocked (48). Inhibition of PDH has been shown to promote aerobic glycolysis and to favor FAO (14). In maturing cardiac myocytes, we envisage that LonP1 plays a pivotal role in calibrating the levels of glucose and fatty acid oxidation by directly regulating PDH and also potentially by directly or indirectly regulating FAO. Further studies with human cardiac myocytes are needed to confirm the role of LonP1 in regulating the metabolic switch in mitochondrial energy substrate utilization and metabolism during cardiac differentiation and maturation.

We have also previously shown that LonP1 is transcriptionally upregulated 3.2-fold during differentiation of hiPSCs derived from human cardiac fibroblasts into beating CMs (day 14), which is consistent with our findings in this current study. In mice, LonP1 is essential for embryonic viability, as a homozygous knockout leads to death during early gastrulation (57). The embryonic absence of LonP1 leads to growth retardation and arrest, which is associated with mitochondrial DNA depletion and mitochondrial dysfunction, thus impairing ATP synthesis by OXPHOS. Taken together, the data presented here strongly support an essential role of LonP1 in optimizing bioenergetics and thus the redox status of during cardiac differentiation and the mature heart.

Our work is distinctly different from previous studies, which performed global proteomic analyses using hiPSC-CMs differentiated for shorter time periods of up to 15, 30–35, and 60 days (25, 31, 34). A common finding among these studies as well as ours is the observation that the differentiation of hiPSC-CMs leads to fundamental changes in energy metabolism. By contrast, global transcriptomics studies that show changes in mRNA levels corresponding to mitochondrial proteins investigated in our study are consistent with our observation at protein levels during CM differentiation (2, 8, 9, 21, 79), although methods, differentiation protocols, and time point vary between the studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of mitochondrial protein fold change from our study and the mRNA-level fold change from other studies observed during cardiac differentiation

| Target Gene | mRNA* | Fold Change Comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Protein (Current Study)† |

|||

| Western | LC-MS | |||

| LONP1 | 3.2 1.7 0.8 |

Baljinnyam et al., 2017 (2) Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

4.5 | 4.0 |

| NDUFS1 | 3.6 1.2 1.4 2.5 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ Cao et al., 2008 (9) Xu et al., 2009 (79) |

NA | 7.8 |

| NDUFB8 | 2.7 1.2 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

1.4 | 1.5 |

| SDHB | 4.0 2.2 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Cao et al., 2008 (9) |

1.3 | 2.3 |

| MT-CO I | NA | NA | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| MT-CYB | 9.5 1.2 |

Baljinnyam et al., 2017 (2) Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

NA | 1.5 |

| ATP5A | 5.6 1.3 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

1.2 | 3.6 |

| RAB9A | 2.5 1.5 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

2.9 | 2.0 |

| CPT1A | 1.5 0.5 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

NA | 3.5 |

| CPT1B | 8.0 0.8 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

4.5 | 1.5 |

| CPT2 | 1.34 0.9 |

Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

NA | 4.6 |

| IDH2 | High 73.3 6.4 |

Zhou et al., 2017 (86) Friedman et al., 2018 (21)‡ Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ |

NA | 3.9 |

| PARKIN | 7.5 | Branco et al., 2019 (8)§ | 1.2 | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Fold change observed in differentiated cardiomyocytes (CMs) when compared with pluripotent or embryonic stem cells, obtained from the literature

Fold change in protein levels measured in the current study by Western blot using cFCMs at day 120 versus 35 and LC MS/MS in cFCMs at day 115 versus 12.

Fold change is calculated based on mean expression of respective transcripts in the definitive cardiomyocyte group at day 30 versus pluripotent cells at day 0 [see Friedman et al. (21) calculated at http://computationalgenomics.com.au/shiny/hipsc2cm/].

§Fold change calculated after averaging the triplicates from day 20 versus day 1 of differentiating CMs [source: Branco et al. (8)].

One study comparing iPSC-CMs, cardiac progenitor cells, and CMs showed that BCAA degradation and ketogenesis are upregulated during differentiation. After 15 days of differentiation, they observed that BCAA metabolism was upregulated by induced ketogenesis-related proteins (31). Similar to the findings reported here, a global study of iPSC-CMs differentiated for ∼30 days versus 14 days also demonstrated a metabolic shift from glycolysis toward OXPHOS (25). IPA also predicted the upregulation of PGC-1α and Rb1, consistent with our findings, in addition to other upstream regulators that were not observed in our study, most likely because the IPA data set we used was limited to mitochondrial proteins. However, another global proteomics study using hESC-CMs differentiated for 35 days unexpectedly showed that enzymes mediating glycolysis were up- (not down-) regulated, and that enzymes mediating OXPHOS were downregulated on day 20 of differentiation, and then restored on day 35 (34). They also observed substantial upregulation during differentiation of the Z-disk-associated PDZ and LIM domain containing protein (PDLIM5). However, the function of this protein during CM differentiation and maturation has yet to be determined.

Our study predicts novel upstream activators (IR and LonP1) and inhibitors (RICTOR, KDM4K4, and KDM5a), which we anticipate may play key roles in cardiomyogenesis and cardioprotection. We acknowledge the limitations of the analysis in terms of replicates and detailed characterization of mitochondria (e.g., size, purity). Although we have validated LonP1, future studies are required to validate the other predicted upstream regulators and the molecular mechanisms underlying their respective functions. Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9 offers a feasible strategy for elucidating these potential pathways and regulators of energy metabolism, which will be critical for in vitro modeling of myocardial diseases and for realizing the potential of iPSC-CMs in regenerative medicine.

Perspectives and Significance

Increasing lines of evidence suggest that mitochondria play a key role in mediating differentiation and maturation of cardiomyocytes. Using comprehensive proteomic approaches, we identified factors upregulated during metabolic maturation of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. These include LonP1, PGC1-α, IR, and Rb1, all of which appear to be involved in mitochondrial quality control mechanisms. Our study provides a premise for future studies to further elucidate the functional involvement of these molecules in the metabolic maturation of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, which will lead to the identification of novel and specific interventions toward the generation of metabolically mature hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and a better understanding of the endogenous mechanism of metabolic alteration during development and regeneration.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HL067724, HL091469, HL112330, HL138720, and AG023039 (to J. Sadoshima); by the Leducq Foundation Transatlantic Network of Excellence 15CBD04 (to J. Sadoshima); by the Busch Biomedical Grant Program (to C. K. Suzuki), and a generous gift from M. Malhotra (to C. K. Suzuki); and by the New Jersey Medical School (NJMS), Core facility matching funds for “Biomarker discovery using pluripotent stem cells” (to D. Fraidenraich). The mass spectrometry data were obtained using an Orbitrap mass spectrometer funded in part by NIH Grants NS046593 and 1S10OD025047-01, for the support of proteomics research at Rutgers Newark campus. Confocal images were obtained at the Confocal Imaging Facility, Cancer Center, NJMS-Rutgers (Luke Fritzky).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.V., C.S., D.F., J.S., E.B., M.T., T.K., T.L., H.L., and L-H.X. conceived and designed research; S.V., S.O., E.B., M.T., T.K., L.Y., T.L., L-H.X., and M.N. performed experiments; S.V., S.O., C.S., D.F., J.S., E.B., M.T., T.K., L.Y., T.L., H.L., L-H.X., and M.N. analyzed data; S.V., S.O., C.S., D.F., J.S., E.B., M.T., T.K., L.Y., T.L., H.L., L-H.X., and M.N. interpreted results of experiments; S.V., S.O., C.S., E.B., M.T., T.K., L.Y., T.L., H.L., L-H.X., and M.N. prepared figures; S.V., C.S., D.F., and E.B. drafted manuscript; S.V., S.O., C.S., D.F., J.S., E.B., M.T., T.L., H.L., L-H.X., and M.N. edited and revised manuscript; S.V., S.O., C.S., D.F., J.S., E.B., and H.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jianyi Zhang (The University of Alabama at Birmingham) for help with hiPSC-derived CMs; Drs. Patricia Fitzgerald‐Bocarsly (Rutgers NJMS) and Sukhwinder Singh (Rutgers NJMS) for help with flow cytometry analysis, and Blair Bell (Rutgers NJMS) and Reema Shah (Rutgers NJMS) for hiPSC cell culture and help with the proteomics data analysis; and Daniela Zablocki (Rutgers NJMS) for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakaki N, Yamashita A, Niimi S, Yamazaki T. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in osteoblastic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells accompanied by mitochondrial morphological dynamics. Biomed Res 34: 161–166, 2013. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.34.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baljinnyam E, Venkatesh S, Gordan R, Mareedu S, Zhang J, Xie LH, Azzam EI, Suzuki CK, Fraidenraich D. Effect of densely ionizing radiation on cardiomyocyte differentiation from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Physiol Rep 5: e13308, 2017. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth E, Stämmler G, Speiser B, Schaper J. Ultrastructural quantitation of mitochondria and myofilaments in cardiac muscle from 10 different animal species including man. J Mol Cell Cardiol 24: 669–681, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93381-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benevolenskaya EV, Murray HL, Branton P, Young RA, Kaelin WG Jr. Binding of pRB to the PHD protein RBP2 promotes cellular differentiation. Mol Cell 18: 623–635, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein SH, Venkatesh S, Li M, Lee J, Lu B, Hilchey SP, Morse KM, Metcalfe HM, Skalska J, Andreeff M, Brookes PS, Suzuki CK. The mitochondrial ATP-dependent Lon protease: a novel target in lymphoma death mediated by the synthetic triterpenoid CDDO and its derivatives. Blood 119: 3321–3329, 2012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-340075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezawork-Geleta A, Brodie EJ, Dougan DA, Truscott KN. LON is the master protease that protects against protein aggregation in human mitochondria through direct degradation of misfolded proteins. Sci Rep 5: 17397, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep17397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bota DA, Ngo JK, Davies KJ. Downregulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death. Free Radic Biol Med 38: 665–677, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branco MA, Cotovio JP, Rodrigues CAV, Vaz SH, Fernandes TG, Moreira LM, Cabral JMS, Diogo MM. Transcriptomic analysis of 3D cardiac differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells reveals faster cardiomyocyte maturation compared to 2D culture. Sci Rep 9: 9229, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45047-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao F, Wagner RA, Wilson KD, Xie X, Fu JD, Drukker M, Lee A, Li RA, Gambhir SS, Weissman IL, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Transcriptional and functional profiling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 3: e3474, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caruso M, Maitan MA, Bifulco G, Miele C, Vigliotta G, Oriente F, Formisano P, Beguinot F. Activation and mitochondrial translocation of protein kinase Cdelta are necessary for insulin stimulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in muscle and liver cells. J Biol Chem 276: 45088–45097, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SH, Suzuki CK, Wu SH. Thermodynamic characterization of specific interactions between the human Lon protease and G-quartet DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 1273–1287, 2008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinnam M, Goodrich DW. RB1, development, and cancer. Curr Top Dev Biol 94: 129–169, 2011. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380916-2.00005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 4, Suppl 1: S60–S67, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crewe C, Kinter M, Szweda LI. Rapid inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase: an initiating event in high dietary fat-induced loss of metabolic flexibility in the heart. PLoS One 8: e77280, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai DF, Danoviz ME, Wiczer B, Laflamme MA, Tian R. Mitochondrial maturation in human pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Int 2017: 5153625, 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/5153625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Defeo-Jones D, Huang PS, Jones RE, Haskell KM, Vuocolo GA, Hanobik MG, Huber HE, Oliff A. Cloning of cDNAs for cellular proteins that bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature 352: 251–254, 1991. doi: 10.1038/352251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Des Rosiers C, Labarthe F, Lloyd SG, Chatham JC. Cardiac anaplerosis in health and disease: food for thought. Cardiovasc Res 90: 210–219, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyson NJ. RB1: a prototype tumor suppressor and an enigma. Genes Dev 30: 1492–1502, 2016. doi: 10.1101/gad.282145.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan L, Hsieh PN, Sweet DR, Jain MK. Krüppel-like factor 15: Regulator of BCAA metabolism and circadian protein rhythmicity. Pharmacol Res 130: 123–126, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldhoff PW, Arnold J, Oesterling B, Vary TC. Insulin-induced activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in skeletal muscle of diabetic rats. Metabolism 42: 615–623, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman CE, Nguyen Q, Lukowski SW, Helfer A, Chiu HS, Miklas J, Levy S, Suo S, Han JJ, Osteil P, Peng G, Jing N, Baillie GJ, Senabouth A, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Murry CE, Wong ES, Ding J, Wang Y, Hudson J, Ruohola-Baker H, Bar-Joseph Z, Tam PPL, Powell JE, Palpant NJ. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of cardiac differentiation from human PSCs reveals HOPX-dependent cardiomyocyte maturation. Cell Stem Cell 23: 586–598.e8, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu GK, Markovitz DM. The human LON protease binds to mitochondrial promoters in a single-stranded, site-specific, strand-specific manner. Biochemistry 37: 1905–1909, 1998. doi: 10.1021/bi970928c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong G, Song M, Csordas G, Kelly DP, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW II. Parkin-mediated mitophagy directs perinatal cardiac metabolic maturation in mice. Science 350: aad2459, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray S, Wang B, Orihuela Y, Hong EG, Fisch S, Haldar S, Cline GW, Kim JK, Peroni OD, Kahn BB, Jain MK. Regulation of gluconeogenesis by Krüppel-like factor 15. Cell Metab 5: 305–312, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellen N, Pinto Ricardo C, Vauchez K, Whiting G, Wheeler JX, Harding SE. Proteomic analysis reveals temporal changes in protein expression in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cells Dev 28: 565–578, 2019. doi: 10.1089/scd.2018.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilgendorf KI, Leshchiner ES, Nedelcu S, Maynard MA, Calo E, Ianari A, Walensky LD, Lees JA. The retinoblastoma protein induces apoptosis directly at the mitochondria. Genes Dev 27: 1003–1015, 2013. doi: 10.1101/gad.211326.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hostetler HA, Lupas D, Tan Y, Dai J, Kelzer MS, Martin GG, Woldegiorgis G, Kier AB, Schroeder F. Acyl-CoA binding proteins interact with the acyl-CoA binding domain of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyl transferase I. Mol Cell Biochem 355: 135–148, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0847-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamakura T, Makiyama T, Sasaki K, Yoshida Y, Wuriyanghai Y, Chen J, Hattori T, Ohno S, Kita T, Horie M, Yamanaka S, Kimura T. Ultrastructural maturation of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in a long-term culture. Circ J 77: 1307–1314, 2013. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz AM. Physiology of the heart. In: Structure of the Heart and Cardiac Muscle. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 21, chapt. 1, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim C, Wong J, Wen J, Wang S, Wang C, Spiering S, Kan NG, Forcales S, Puri PL, Leone TC, Marine JE, Calkins H, Kelly DP, Judge DP, Chen H-SV. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature 494: 105–110, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Jeon JM, Kwon OK, Choe MS, Yeo HC, Peng X, Cheng Z, Lee MY, Lee S. comparative proteomic analysis reveals the upregulation of ketogenesis in cardiomyocytes differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Proteomics 19: e1800284, 2019. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kita-Matsuo H, Barcova M, Prigozhina N, Salomonis N, Wei K, Jacot JG, Nelson B, Spiering S, Haverslag R, Kim C, Talantova M, Bajpai R, Calzolari D, Terskikh A, McCulloch AD, Price JH, Conklin BR, Chen HSV, Mercola M. Lentiviral vectors and protocols for creation of stable hESC lines for fluorescent tracking and drug resistance selection of cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 4: e5046–e5046, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klose RJ, Yan Q, Tothova Z, Yamane K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Gilliland DG, Zhang Y, Kaelin WG Jr. The retinoblastoma binding protein RBP2 is an H3K4 demethylase. Cell 128: 889–900, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konze SA, Werneburg S, Oberbeck A, Olmer R, Kempf H, Jara-Avaca M, Pich A, Zweigerdt R, Buettner FFR. Proteomic analysis of human pluripotent stem cell cardiomyogenesis revealed altered expression of metabolic enzymes and PDLIM5 isoforms. J Proteome Res 16: 1133–1149, 2017. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaFramboise WA, Petrosko P, Krill-Burger JM, Morris DR, McCoy AR, Scalise D, Malehorn DE, Guthrie RD, Becich MJ, Dhir R. Proteins secreted by embryonic stem cells activate cardiomyocytes through ligand binding pathways. J Proteomics 73: 992–1003, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai L, Leone TC, Keller MP, Martin OJ, Broman AT, Nigro J, Kapoor K, Koves TR, Stevens R, Ilkayeva OR, Vega RB, Attie AD, Muoio DM, Kelly DP. Energy metabolic reprogramming in the hypertrophied and early stage failing heart: a multisystems approach. Circ Heart Fail 7: 1022–1031, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamming DW, Demirkan G, Boylan JM, Mihaylova MM, Peng T, Ferreira J, Neretti N, Salomon A, Sabatini DM, Gruppuso PA. Hepatic signaling by the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2). FASEB J 28: 300–315, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-237743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee NK, Choi YG, Baik JY, Han SY, Jeong DW, Bae YS, Kim N, Lee SY. A crucial role for reactive oxygen species in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Blood 106: 852–859, 2005. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc 8: 162–175, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lilley K, Zhang C, Villar-Palasi C, Larner J, Huang L. Insulin mediator stimulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatases. Arch Biochem Biophys 296: 170–174, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90559-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu T, Lu B, Lee I, Ondrovicová G, Kutejová E, Suzuki CK. DNA and RNA binding by the mitochondrial lon protease is regulated by nucleotide and protein substrate. J Biol Chem 279: 13902–13910, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Lan L, Huang K, Wang R, Xu C, Shi Y, Wu X, Wu Z, Zhang J, Chen L, Wang L, Yu X, Zhu H, Lu B. Inhibition of Lon blocks cell proliferation, enhances chemosensitivity by promoting apoptosis and decreases cellular bioenergetics of bladder cancer: potential roles of Lon as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target in bladder cancer. Oncotarget 5: 11209–11224, 2014. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopaschuk GD, Jaswal JS. Energy metabolic phenotype of the cardiomyocyte during development, differentiation, and postnatal maturation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56: 130–140, 2010. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e74a14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Bigas N, Kisiel TA, Dewaal DC, Holmes KB, Volkert TL, Gupta S, Love J, Murray HL, Young RA, Benevolenskaya EV. Genome-wide analysis of the H3K4 histone demethylase RBP2 reveals a transcriptional program controlling differentiation. Mol Cell 31: 520–530, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mummery CL, Zhang J, Ng ES, Elliott DA, Elefanty AG, Kamp TJ. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells to cardiomyocytes: a methods overview. Circ Res 111: 344–358, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicolay BN, Danielian PS, Kottakis F, Lapek JD Jr, Sanidas I, Miles WO, Dehnad M, Tschöp K, Gierut JJ, Manning AL, Morris R, Haigis K, Bardeesy N, Lees JA, Haas W, Dyson NJ. Proteomic analysis of pRb loss highlights a signature of decreased mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Genes Dev 29: 1875–1889, 2015. doi: 10.1101/gad.264127.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nie X, Li M, Lu B, Zhang Y, Lan L, Chen L, Lu J. Down-regulating overexpressed human Lon in cervical cancer suppresses cell proliferation and bioenergetics. PLoS One 8: e81084, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nimmo GAM, Venkatesh S, Pandey AK, Marshall CR, Hazrati L-N, Blaser S, Ahmed S, Cameron J, Singh K, Ray PN, Suzuki CK, Yoon G. Bi-allelic mutations of LONP1 encoding the mitochondrial LonP1 protease cause pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency and profound neurodegeneration with progressive cerebellar atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 28: 290–306, 2018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Page E, McCallister LP. Quantitative electron microscopic description of heart muscle cells. Application to normal, hypertrophied and thyroxin-stimulated hearts. Am J Cardiol 31: 172–181, 1973. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)91030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, Bernal-Llinares M, Hewapathirana S, Kundu DJ, Inuganti A, Griss J, Mayer G, Eisenacher M, Pérez E, Uszkoreit J, Pfeuffer J, Sachsenberg T, Yilmaz S, Tiwary S, Cox J, Audain E, Walzer M, Jarnuczak AF, Ternent T, Brazma A, Vizcaíno JA. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res 47: D442–D450, 2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinti M, Gibellini L, De Biasi S, Nasi M, Roat E, O’Connor JE, Cossarizza A. Functional characterization of the promoter of the human Lon protease gene. Mitochondrion 11: 200–206, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinti M, Gibellini L, Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Gant TW, Morselli E, Nasi M, Salomoni P, Mussini C, Cossarizza A. Upregulation of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial LON protease in HAART-treated HIV-positive patients with lipodystrophy: implications for the pathogenesis of the disease. AIDS 24: 841–850, 2010. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833779a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinti M, Gibellini L, Nasi M, De Biasi S, Bortolotti CA, Iannone A, Cossarizza A. Emerging role of Lon protease as a master regulator of mitochondrial functions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857: 1300–1306, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poon E, Keung W, Liang Y, Ramalingam R, Yan B, Zhang S, Chopra A, Moore J, Herren A, Lieu DK, Wong HS, Weng Z, Wong OT, Lam YW, Tomaselli GF, Chen C, Boheler KR, Li RA. Proteomic analysis of human pluripotent stem cell-derived, fetal, and adult ventricular cardiomyocytes reveals pathways crucial for cardiac metabolism and maturation. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 427–436, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Porter GA Jr, Hom J, Hoffman D, Quintanilla R, de Mesy Bentley K, Sheu SS. Bioenergetics, mitochondria, and cardiac myocyte differentiation. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 31: 75–81, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quirós PM, Bárcena C, López-Otín C. Lon protease: A key enzyme controlling mitochondrial bioenergetics in cancer. Mol Cell Oncol 1: e968505, 2014. doi: 10.4161/23723548.2014.968505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quirós PM, Español Y, Acín-Pérez R, Rodríguez F, Bárcena C, Watanabe K, Calvo E, Loureiro M, Fernández-García MS, Fueyo A, Vázquez J, Enríquez JA, López-Otín C. ATP-dependent Lon protease controls tumor bioenergetics by reprogramming mitochondrial activity. Cell Reports 8: 542–556, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao V, Merante F, Weisel RD, Shirai T, Ikonomidis JS, Cohen G, Tumiati LC, Shiono N, Li RK, Mickle DA, Robinson BH. Insulin stimulates pyruvate dehydrogenase and protects human ventricular cardiomyocytes from simulated ischemia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 116: 485–494, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robertson C, Tran DD, George SC. Concise review: maturation phases of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells 31: 829–837, 2013. doi: 10.1002/stem.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Ma SP, Yeager K, Chen T, Song L, Sirabella D, Morikawa K, Teles D, Yazawa M, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells. Nature 556: 239–243, 2018. [Erratum in Nature 572: E16–E17, 2019]. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saito T, Nah J, Oka SI, Mukai R, Monden Y, Maejima Y, Ikeda Y, Sciarretta S, Liu T, Li H, Baljinnyam E, Fraidenraich D, Fritzky L, Zhai P, Ichinose S, Isobe M, Hsu CP, Kundu M, Sadoshima J. An alternative mitophagy pathway mediated by Rab9 protects the heart against ischemia. J Clin Invest 129: 802–819, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI122035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sansbury BE, DeMartino AM, Xie Z, Brooks AC, Brainard RE, Watson LJ, DeFilippis AP, Cummins TD, Harbeson MA, Brittian KR, Prabhu SD, Bhatnagar A, Jones SP, Hill BG. Metabolomic analysis of pressure-overloaded and infarcted mouse hearts. Circ Heart Fail 7: 634–642, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schaper J, Meiser E, Stämmler G. Ultrastructural morphometric analysis of myocardium from dogs, rats, hamsters, mice, and from human hearts. Circ Res 56: 377–391, 1985. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.56.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP Jr, Aponte AM, Shen RF, Balaban RS, Finkel T. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem 281: 27643–27652, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Searle BC. Scaffold: a bioinformatic tool for validating MS/MS-based proteomic studies. Proteomics 10: 1265–1269, 2010. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strauss KA, Jinks RN, Puffenberger EG, Venkatesh S, Singh K, Cheng I, Mikita N, Thilagavathi J, Lee J, Sarafianos S, Benkert A, Koehler A, Zhu A, Trovillion V, McGlincy M, Morlet T, Deardorff M, Innes AM, Prasad C, Chudley AE, Lee IN, Suzuki CK. CODAS syndrome is associated with mutations of LONP1, encoding mitochondrial AAA+ Lon protease. Am J Hum Genet 96: 121–135, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun H, Olson KC, Gao C, Prosdocimo DA, Zhou M, Wang Z, Jeyaraj D, Youn JY, Ren S, Liu Y, Rau CD, Shah S, Ilkayeva O, Gui WJ, William NS, Wynn RM, Newgard CB, Cai H, Xiao X, Chuang DT, Schulze PC, Lynch C, Jain MK, Wang Y. Catabolic defect of branched-chain amino acids promotes heart failure. Circulation 133: 2038–2049, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takebayashi S, Tanaka H, Hino S, Nakatsu Y, Igata T, Sakamoto A, Narita M, Nakao M. Retinoblastoma protein promotes oxidative phosphorylation through upregulation of glycolytic genes in oncogene-induced senescent cells. Aging Cell 14: 689–697, 2015. doi: 10.1111/acel.12351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]