Keywords: butyrate, immature intestinal inflammation, mucus genes, tight junction genes

Abstract

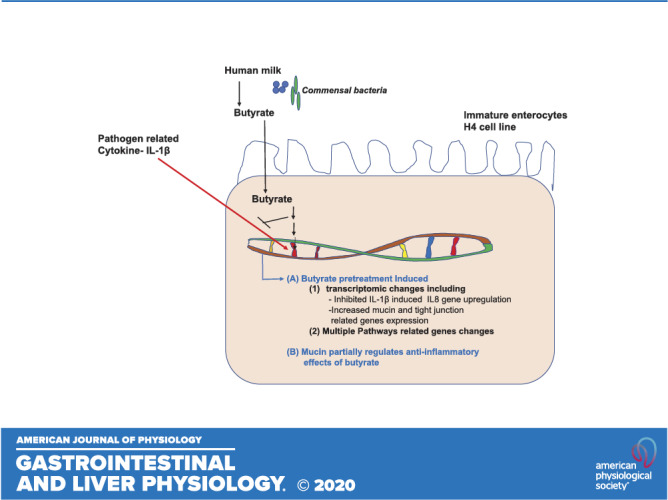

Infants born under 1,500 g have an increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in the ileum and the colon, which is a life-threatening intestinal necrosis. This is in part due to excessive inflammation in the immature intestine to colonizing bacteria because of an immature innate immune response. Breastmilk complex carbohydrates create metabolites of colonizing bacteria in the form of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). We studied the effect of breastmilk metabolites, SCFAs, on immature intestine with regard to anti-inflammatory effects. This showed that acetate, propionate, and butyrate were all anti-inflammatory to an IL-1β inflammatory stimulus. In this study, to further define the mechanism of anti-inflammation, we created transcription profiles of RNA from immature human enterocytes after exposure to butyrate with and without an IL-1β inflammatory stimulus. We demonstrated that butyrate stimulates an increase in tight-junction and mucus genes and if we inhibit these genes, the anti-inflammatory effect is partially lost. SCFAs, products of microbial metabolism of complex carbohydrates of breastmilk oligosaccharides, have been found with this study to induce an anti-IL-1β response that is associated with an upregulation of tight junctions and mucus genes in epithelial cells (H4 cells). These studies suggest that breastmilk in conjunction with probiotics can reduce excessive inflammation with metabolites that are anti-inflammatory and stimulate an increase in the mucosal barrier.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study extends previous observations to define the anti-inflammatory properties of butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid produced by the metabolism of breastmilk oligosaccharides by colonizing bacteria. Using transcription profiling of immature enterocyte genes, after exposure to butyrate and an IL-1β stimulus, we showed that tight-junction genes and mucus genes were increased, which contributed to the anti-inflammatory effect.

INTRODUCTION

Butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) found in the immature intestine, is the end product of the metabolism of the intestinal beneficial colonizing bacteria fermentation of undigested carbohydrate as found in human milk oligosaccharides (35). Butyrate plays an important role in innate immunity and cell metabolism (36). We have reported that SCFAs (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) are anti-inflammatory in human immature enterocytes (6), but their impact on global gene expression and maturation in immature enterocytes is unclear. Studies exploring the impact of butyrate on the genes involved in the mucosal barrier in immature enterocyte maturation are key to finding new signaling pathways to prevent immaturity-associated intestinal inflammatory disease seen in necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). NEC is an inflammatory necrosis of the distal small intestine and colon that commonly affects very premature infants. NEC mortality remains consistently high since it was first reported five decades ago (22).

There is no specific treatment for NEC beyond broad-spectrum antibiotics and intestinal resection, and current efforts have focused on preventive strategies (14, 41). A recent study suggests that prevention is most effective when breast milk and probiotics are given together (30). This study information uses historic controls, which reduces some of the conclusions. However, other studies by Lin et al. (18) using Infloran and exclusive breastfeeding had excellent results, and breastmilk, per se, has been shown to be anti-inflammatory. This suggests that breast milk metabolites may play a critical role in prevention, but the mechanisms of that effect are as yet unknown. We hypothesis that the breast milk metabolite butyrate may affect the gene profile under normal and inflammatory conditions in immature enterocytes including genes regulating enterocyte maturation of the mucosal barrier. To address this hypothesis, we have used transcription profiles of RNA from human immature enterocytes to detect the gene profile changes affected by butyrate on an immature human small intestinal epithelial cell line (H4 cells) under normal and inflammatory conditions.

In gene profile analysis, we focused on the effects of butyrate on innate immunity and barrier function-related gene changes confirmed by the use of real-time quantitative (q)RT-PCR to validate gene expression in the transcription profiles. We found that in addition to the prevention of IL-1β-induced inflammatory gene changes, butyrate can enhance barrier function-related gene expression and prevent IL-1β-induced downregulation of barrier-function related genes. The effects of butyrate on immature enterocyte barrier function were also partially verified in in vivo studies. Since we used organ cultures of the entire intestine, many cell types besides enterocytes were represented including immune cells and endothelial cells. Therefore, these in vitro studies can be only partial confirmation of our in vitro cellular studies. We did not find cytotoxicity of butyrate on immature enterocytes in vitro or in vivo. Our results suggested that butyrate has a beneficial effect on both innate immunity and barrier function in immature enterocytes. These observations may provide a new preventative strategy for NEC and would benefit the premature infant with potential use for those infants at high risk for NEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), nonessential amino acid (NEAA; 100×), glutamine (100×), antibiotic/antimycotic solution (100×), HEPES buffer (1 M), and sodium pyruvate (100 mM) were obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Diego, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Humulin R regular insulin human injection material (100 U/ml) was obtained from Lilly (Indianapolis, IN). Tissue culture plastics were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The RNAeasy Mini kits were obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis Supermix and SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix Universal were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Recombinant human IL-1β and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for human IL-8 and mouse macrophage inflammatory protein2 (MIP2) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Sodium butyrate was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Natick, MA).

Cell Cultures and Treatments

H4 cells, a human nontransformed primary intestinal epithelial cell line characterized by our laboratory (IRB 2018-P002987), were used as an in vitro model of the immature intestine (33). The cells were routinely maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% NEAA, 1% glutamine, 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.2 U/ml human recombinant insulin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide, humidified atmosphere. H4 cells were incubated with or without butyrate 20 mM in the absence or presence of 1 ng/ml IL-1β. IL-1β was added to cell culture medium 30 min after the administration of butyrate.

Transcriptome Studies

Total RNA was isolated from H4 cells treated with or without butyrate (20 mM) in the absence or presence of 1 ng/ml IL-1β (for 4 h), with TRIzol reagent (three replicates per sample). Then, extracted RNA was purified using the RNeasy cleanup kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A cDNA library was constructed and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqTM 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). After low-quality reads were removed with ambiguous nucleotides and sequencing adapters, high-quality reads (clean reads) were mapped to the human transcriptome reference (hp19/GRCh37.75) using STAR. The annotated transcripts were normalized by RPKM values (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). Significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as those with a fold change of >2 and a false discovery rate of < 0.05. Gene annotation was done by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotation. To reduce the sample variability, three replicates of harvested H4 cells were pooled into one sample. A total of three samples were prepared from each treatment.

Measurement of IL-8 Production

IL-8 concentrations in H4 cell culture media were determined by ELISA (Human CXCL-8/IL-8, DuoSet ELISA, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan Go, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Animals

C57BL/6 mice obtained from the Jackson Laboratory were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Animal procedures had been previously approved by the MGH Subcommittee on Research Animal Care and Use Committee (2018N000070). Animals were given water and standard laboratory chow ad libitum. Littermate newborn pups were randomly divided into PBS and butyrate (Buty) groups. Each pup at postnatal day 4 received PBS (10 µl) or Buty (100 mM, 10 µl) via gavage once per day for 3 days followed by twice per day for 4 days, and then all pups in each group were euthanized. The intestinal tissue of ileum and colon were collected and cut into 3-mm pieces and maintained in organ culture media as described previously (19, 20). Briefly, these media were made by Opti-MEM I medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 0.5 U/ml insulin, and 200 ng/ml recombined mouse epidermal growth factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 5 mg/ml transferrin, 0.06 mM sodium selenite, 200 nM hydrocortisone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and an antibiotic-antimycotic cocktail (100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml fungizone antimycotic) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher). After 1 h at 37°C, the tissues were stimulated with or without 1 ng/ml of recombinant mouse IL-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 24 h. The supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C for ELISA analysis, and the tissues were kept at −80°C for total RNA isolation.

Measurement of Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 2 Production

MIP2 concentrations in mouse ileal and colonic tissue culture media were determined by ELISA (Mouse CXCL-2/MIP-2, DuoSet ELISA, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan Go, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from H4 cells and mouse ileum tissue with RNA RNeasy MIini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Isolated RNA was treated with DNase I (Fermentas) to remove remaining DNA. RNA yield was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The cDNA was amplified using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Philadelphia, PA). For Quantitative qRT-PCR of human FZD4, SERPINE1, CDK6, ZP4, CXCL3, IL6, CXCL8, CXCL10, OCLN, CLDN4, CLDN11, CLDN15, MUC20, and GADPH, and mouse TJP1, OCLN, CLDN1, CLDN3, CLDN4, MUC1, MUC2, MUC4,and MUC19 was performed, and the primer sequences used for these genes are shown in Supplemental Table S1 (all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12678947). The qRT-PCR with probes was performed with the iQ SYBR Supermix (Bio-Rad).

Transcript levels were corrected to GADPH (human) or β-actin (mouse) and fold expression levels of gene of interests were calculated by their Ct values as follows: unstimulated condition: ΔCt control = Ct target gene control − Ct GADPH/β-actin control; stimulated condition: ΔCt treated = Ct target gene treated − Ct GADPH/β-actin treated; and ΔCt(control) − ΔCt(treated) values = ΔΔCt, the fold change in mRNA = 2ΔΔCt.

H4 Cell Line Subjected to Mucin Inhibitor

To investigate whether the function of mucin and tight junction in butyrate prevented IL-1β-induced inflammation in H4 cells, H4 cells were pretreated with the mucin inhibitor Talniflumate (0.01 mg/ml and 0.001 mg/ml) or occluding proteolysis phenylarsine oxide (data was not shown), respectively, for 30 min before butyrate (20 mM, 30 min) treatment and then exposed to 1 ng/ml of recombinant human IL-1β (R&D Systems) for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C for IL8 ELISA analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. Unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare the mean of two groups. One-way ANOVA and post hoc tests were used to compare the mean of multiple groups. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001) (GraphPad Prism 6).

RESULTS

Quantitative Transcriptome Analysis of the Effects of Butyrate on Immature Human Enterocytes (H4 Cells)

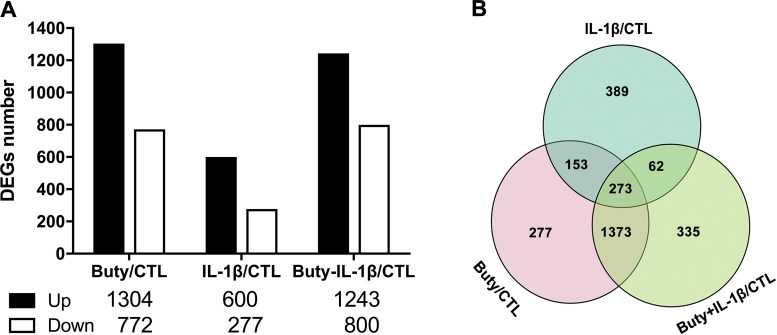

To define the effects of butyrate on gene variation under normal conditions or in response to inflammation in H4 cells, the transcriptomes were compared among butyrate and butyrate with or without IL-1β (Fig. 1). In comparison with the control, 1,304 upregulated and 772 downregulated genes induced by butyrate alone were identified. These changes were similar to the results obtained from butyrate-IL-1β treatment, in which 1,243 up- and 800 downregulated genes were identified. IL-1β stimulation alone induced 600 upregulated genes, which was more than 2 times the number of downregulated genes (277 genes) (Fig. 1A). A Venn diagram was constructed to further examine the specific and the common gene expression profiles among the different treatments by overlapping the different groups’ differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after each was compared with the control (Fig. 1B). The circle on the bottom left represents DEGs induced by butyrate alone, in which the pink area (277 genes) represents the specific DEGs induced by butyrate alone, while the rest of the areas in this circle represent the number of the overlapping DEGs of butyrate alone with the other treatments. Similarly, in comparison with the control, butyrate-IL-1β treatment induced a number of specific DEGs at 355, and IL-1β alone induced a number of specific DEGs at 389. The overlapping area in the middle of the Venn diagram represents the DEGs that are common among all conditions. It is 273 out of 2872 DEGs (9.5%) suggesting different treatments can induce specific changes, common of each other and common of all gene changes.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in H4 cells after exposure to butyrate and IL-1β. H4 cells were pretreated with 20 mM of butyrate for 30 min before IL-1β stimulation (1 ng/ml for 4 h). A: histogram showing the number of DEGs relative to the control. B: Venn diagram showing the genes, treated with butyrate or IL-1 β (with or without butyrate) were significantly regulated (P < 0.05) by comparison with the control. CTL, control group; Buty, individual butyrate group; Buty+ IL-1β, combination of butyrate and IL-1β group.

Subsequently, we analyzed the inflammatory DEGs with different treatments. We found that butyrate inhibited IL-1β- induced CX3XL1, CXCL5, and IL-6 gene expression (Table 1). By comparison with the control group, we also found that there were some differences in the immunity/inflammation-related pathways in IL-1β-stimulated cells with and without butyrate pretreatment (Supplemental Fig. S1). To further study the underlying molecular basis for butyrate anti-inflammation, the top 10 inflammation-related Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways that are significantly enriched by DEGs between butyrate-IL-1β and IL-1β alone in H4 cells were selected (Supplemental Fig. S2). The results showed that except for the inflammatory pathways, protein synthesis, and intercellular connection-associated pathways such as ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, and Hippo signaling pathway were all activated by butyrate-IL-1β treatment.

Table 1.

Inflammation related differentially expressed genes induced by butyrate, IL-1β, or butyrate + IL-1β compared with control in H4 cells

| Gene Name | IL-1β/Con |

Buty+ IL-1β/Con |

Buty/Con |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log2FC | P Value | Log2FC | P Value | Log2FC | P Value | |

| CX3CL1(cy-ch) | 10.17 | 0 | 5.80 | 8.18E−34 | 8.34 | 1.98E−197 |

| CXCL5 | 8.29 | 1.03E−84 | 2.99 | 1.32E−05 | 4.75 | 2.31E−20 |

| IL6(cy) | 6.89 | 0 | −2.14 | 2.65E−36 | 3.15 | 3.89E−269 |

| IL13RA2 | 1.11 | 1.94E−09 | −1.19 | 6.22E−07 | −1.08 | 2.39E−06 |

| TNFRSF1B | 2.68 | 1.79E−39 | 3.36 | 1.90E−71 | ||

| CXCL2(ch) | 11.38 | 0 | 10.17 | 0 | ||

| CCL20(cy-ch) | 8.49 | 9.95E−38 | 10.14 | 1.43E−115 | ||

| CXCL1(ch) | 10.80 | 0 | 9.46 | 0 | ||

| TNFRSF9 | 8.31 | 1.20E−29 | 8.95 | 2.46E−43 | ||

| CXCL3 | 12.04 | 0 | 8.82 | 0 | ||

| CXCL8 | 8.29 | 0 | 7.08 | 0 | ||

| CXCL6 | 6.94 | 1.72E−271 | 4.80 | 1.29E−65 | ||

| CXCL11 | 5.67 | 3.17E−99 | 4.36 | 5.79E−40 | ||

| CXCL10 | 6.26 | 0 | 3.72 | 2.30E−115 | ||

| IL1A (IL-1α) | 6.21 | 1.03E−90 | 3.67 | 4.17E−19 | ||

| IL7 | 1.88 | 1.08E−57 | 2.87 | 2.05E−166 | ||

| TNFAIP8 | 3.81 | 0 | 2.85 | 0 | ||

| IL34 | 3.73 | 9.40E−16 | 2.76 | 3.95E−07 | ||

| IL1B (IL-1β) | 8.39 | 1.36E−165 | 2.62 | 0.001 | ||

| IL18RAP | 3.47 | 1.93E−17 | 2.44 | 1.37E−07 | ||

| IL18R1 | 3.21 | 2.84E−215 | 1.20 | 2.43E−26 | ||

| IFNAR2 | 2.79 | 0 | 1.07 | 2.08E−54 | ||

| TNFAIP6 | 6.58 | 2.81E−296 | ||||

| TNFAIP3 | 6.57 | 0 | ||||

| IL10 | 5.99 | 6.59E−39 | ||||

| IL4I1 | 3.87 | 1.50E−57 | ||||

| IL10RB-AS1 | 3.46 | 2.21E−53 | ||||

| IL32 | 3.30 | 3.82E−168 | ||||

| TNFSF15 | 2.80 | 1.60E−103 | ||||

| IFNGR2 | 2.29 | 0 | ||||

| IL1RN | 1.95 | 2.75E−46 | ||||

| IL15 | 1.94 | 3.38E−67 | ||||

| IL1RL1 | 1.51 | 1.08E−52 | ||||

| C3 | 1.40 | 5.21E−15 | ||||

| IL21R | −1.48 | 1.08E−17 | ||||

| IL17RD | 3.70 | 6.29E−25 | 3.79 | 8.96E−28 | ||

| IL16 | 2.99 | 5.63E−21 | 3.70 | 1.20E−36 | ||

| IL18BP | 1.40 | 3.65E−15 | 1.68 | 6.14E−24 | ||

| IL12A | 1.11 | 4.33E−30 | 1.34 | 9.27E−50 | ||

| IL1RAP | 1.39 | 7.87E−144 | 1.32 | 1.94E−133 | ||

| IL27RA | −1.61 | 4.41E−30 | −1.11 | 1.84E−17 | ||

| IL1RL2 | −1.29 | 2.71E−07 | −1.45 | 2.53E−09 | ||

| IL4R | −1.74 | 2.86E−111 | −1.60 | 3.00E−97 | ||

| CXCR4 | 4.00 | 5.74E−44 | ||||

| TNFSF18 | −1.16 | 2.71E−09 | ||||

| IL21-AS1 | −1.20 | 8.28E−09 | ||||

H4 cells treated with butyrate, IL-1β, or butyrate + IL-1β were subjected to RNA sequencing transcriptome analysis. Differentially expressed gene fold change (FC) in comparison with the control by Log2FC (mean of Log2 treatment group − mean of Log2 control group) are shown.

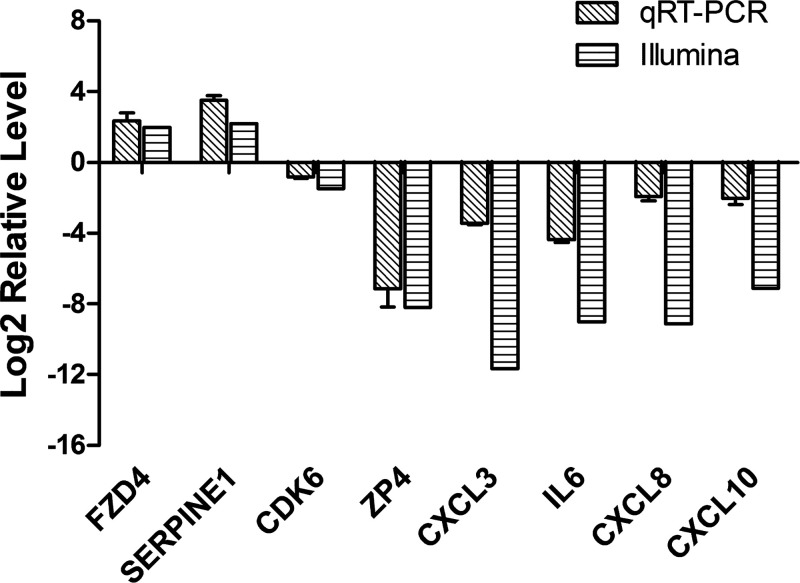

Validating the RNA Sequence Results with Real-Time qRT-PCR

To validate the transcription profiling results from RNA sequences, a total of eight immune related genes from DEGs in butyrate-IL-β versus IL-β alone were selected to run real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (real-time qRT-PCR). The primers of these genes are shown in Supplemental Table S1. The results showed that the differential gene expression was consistent between the two independent methods of analysis (real-time qRT-PCR and RNA sequence-illumina), because the expression of the eight genes changed in the same directions, although there were quantitative differences between the transcriptomic analysis and qRT-PCR results (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of gene expression ratios that were obtained by RNA-seq and quantitative (q)RT-PCR. The horizontal striped bars represent RNA-seq data, and the diagonal striped bars represent the qRT-PCR data. Results are expressed of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

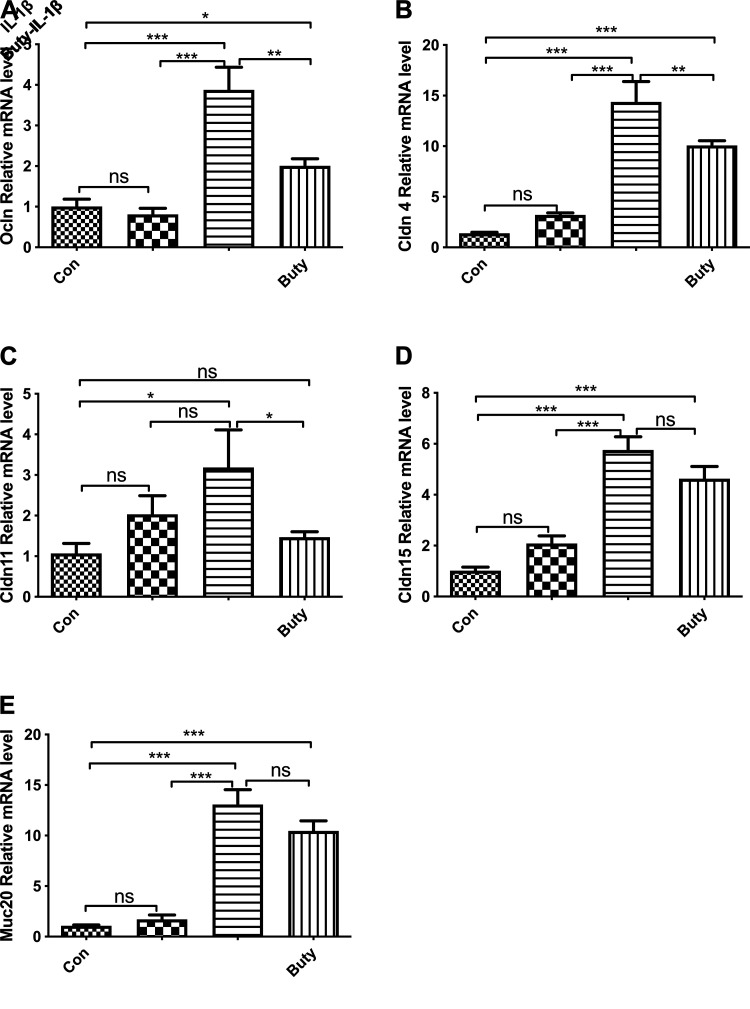

Butyrate Regulates Tight Junction and Mucin-Related Gene Expression During IL-1-Β-Induced Inflammation in Human Immature Enterocytes (H4 Cells)

To investigate if butyrate regulates tight junction and mucin-related gene expression, nine target genes involved in tight junction and mucin signaling pathways were selected for analysis from the transcriptome data based on the gene average expression level (count per million) (Table 2). The results showed that butyrate-IL-1β treatment significantly induced Gap Junction Protein Alpha 3 (GJA3), Occludin (OCLN), Claudin 2 (CLDN2), CLDN4, CLDN11, CLDN15, and Mucin 20 (MUC20) gene expression in comparison with the control and IL-1β stimulation alone (in both conditions P < 0.05, not marked in Table 2). Except GJA3, CLDN2, CLDN5, and MUC12, the remaining five genes were validated by real-time qRT-PCR in H4 cells (Fig. 3). The results showed that the mRNA expression of these five genes, OCLN, CLDN4, CLDN11, CLDN15, and MUC20, was significantly increased by butyrate -IL-1β stimulation compared with both the control and IL-1β alone. However, there was not a significant increase of CLN11 mRNA in the butyrate- IL-1β group compared with IL-1β alone, but an induction of the CLN11 mRNA level was still observed in this condition. These findings confirmed our transcriptome data, suggesting that butyrate treatment modulated the expression levels of the genes associated with tight junction and mucin under normal conditions and during IL-1β stimulation.

Table 2.

Tight junction and mucin-related differentially expressed genes in H4 cells

| Gene Name | Description | Gene Average Expression Level, counts/million |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | IL-1β | Buty-IL-1β | Buty | ||

| GJA3 | Gap junction protein, Α 3 | 0.3379 | 0.0820 | 1.6378 | 1.0491 |

| OCLN | Occludin | 0.7479 | 1.2779 | 4.1632 | 4.2526 |

| CLDN2 | Claudin 2 | 0.2680 | 0.2011 | 0.8982 | 0.4684 |

| CLDN4 | Claudin 4 | 0.3939 | 0.5048 | 2.7770 | 2.9202 |

| CLDN5 | Claudin 5 | 0.0473 | 0.9430 | 0.4573 | 1.5787 |

| CLDN11 | Claudin 11 | 0.4001 | 0.4146 | 1.1376 | 1.3550 |

| CLDN15 | Claudin 15 | 1.7065 | 1.8939 | 3.5100 | 4.0294 |

| MUC12 | Mucin 12 | 0.4985 | 0.9278 | 0.2057 | 0.3486 |

| MUC20 | Mucin 20 | 0.3270 | 0.3832 | 1.9174 | 3.0273 |

H4 cells treated with butyrate, IL-1β, or butyrate + IL-1β were subjected to RNA sequencing transcriptome analysis. Tight-junction and mucin-related differentially expressed genes by gene average expression level (counts/million) from RNA sequence Illumina data are shown.

Figure 3.

Effect of butyrate and IL-1β on tight junction and mucin-related genes in H4 cells. H4 cells were pretreated with 20 mM of butyrate for 30 min before IL-1β stimulation (1 ng/ml for 4 h). mRNA expression of Occludin (Ocln; A), Claudin4 (Cldn4; B), Cldn11 (C), Cldn15 (D), and mucin20 (Muc20) were determined by real-time qRT-PCR. Data are represented as means ± SE of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests were used for statistic, n = 3. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

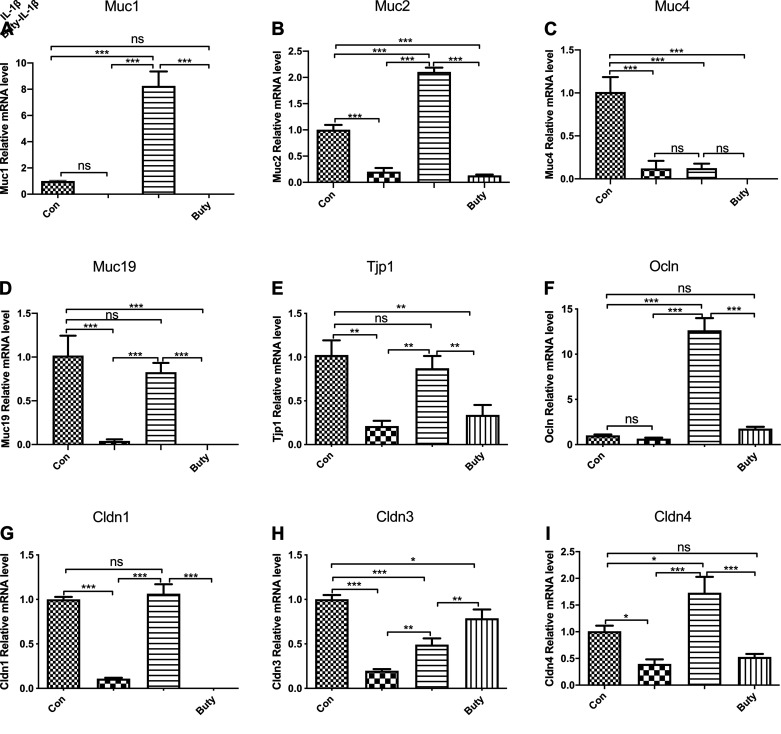

Butyrate Increased Mucin and Tight Junction-Related Genes in Vivo

To investigate if butyrate increases mucin and tight junction-related genes in response to IL-1β stimulation in immature mice, mRNA fold changes of the genes was determined by real-time qRT-PCR in ileum tissue. We found that the expression levels of Muc1 (Fig. 4A), MUC2 (Fig. 4B), MUC4 (Fig. 4C), and MUC19 (Fig. 4D). Tight Junction Protein 1 (TJP1) (Fig. 4E), OCLN (Fig. 4F), CLDN1 (Fig. 4G), and CLDN3 (Fig. 4H) in butyrate-IL-1β treatment group were significantly higher than those in IL-1β stimulation group alone. In addition, compared with IL-1β stimulation alone, mucin-related gene (MUC1, MUC2, and MUC19) expressions were increased significantly by butyrate-IL-1β treatment but not MUC4 (Fig. 4I). These results were also consistent with the results in H4 cells.

Figure 4.

Induction of mucin and tight junction related genes mRNA expression in mouse ileum induced by IL-1β pretreated with butyrate. Ileum tissue collected from control, and mice administered with butyrate were incubated for 24 h with or without IL-1β. mRNA levels of Muc1 (A), Muc2 (B), Muc4 (C), Muc19 (D), Tjp1 (E), Occln (F), Cldn 1(G), Cldn3 (H), and Cldn 4 (I) were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are represented as means ± SE of 2 independent experiments; n = 6 for each experiment. One-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests were used for statistic. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

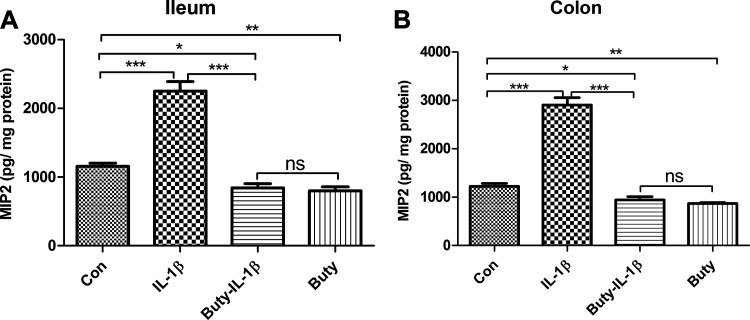

Butyrate Has an Anti-Inflammatory Effect in the Newborn Mouse

To investigate if butyrate has an anti-inflammatory effect on immature intestinal epithelium in vivo, C57BL/6 littermate neonatal mice were orally administrated with PBS or butyrate followed by intestinal tissue exposure to IL-1β stimulation in vitro. As shown in Fig. 5, butyrate significantly reduced IL-1β-induced macrophage inflammatory protein2 (MIP2) secretion in newborn mice small intestine (ileum) and colon organ cultures confirming the anti-inflammatory effect of butyrate on immature mouse intestine. This observation in mice was consistent with the transcription profiling results in H4 cells.

Figure 5.

Butyrate reduced the macrophage inflammatory protein2 (MIP2) secretion in neonatal mouse ileum and colon in response to IL-1β stimulation. Ileum (A) and colon (B) tissue collected from mouse fed with PBS (control) or butyrate were incubated with or without IL-1β for 24 h. The secretion of MIP2 into the supernatants was assayed by ELISA. Data are represented as means ± SE from 2 independent experiments; n = 6 for each experiment. One-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests were used for statistic. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

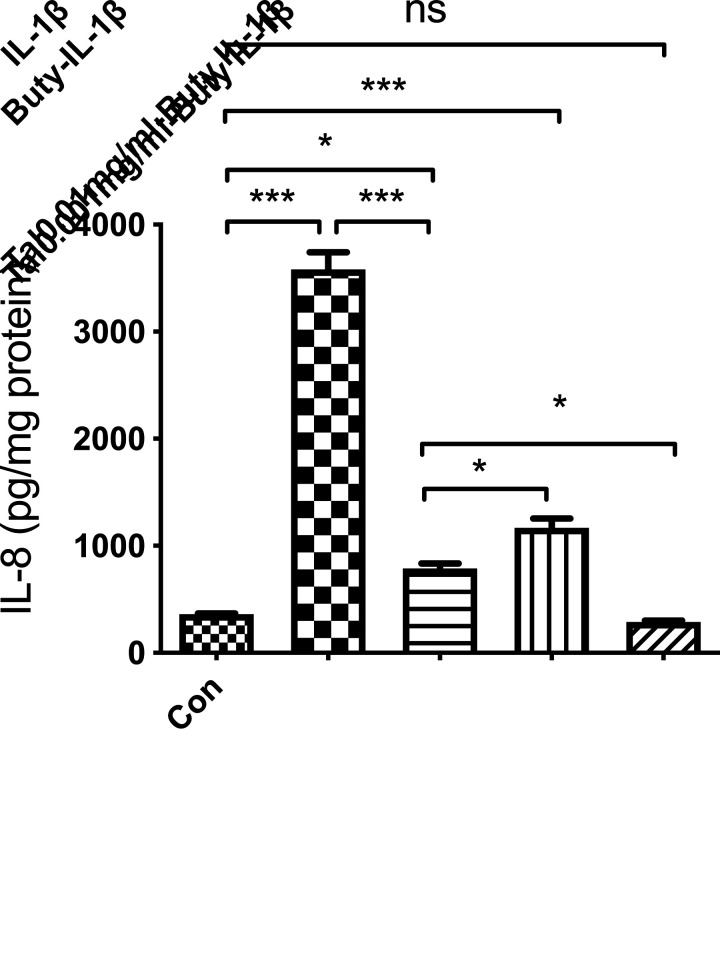

Mucin-Related Genes Are Involved in the Regulation of Butyrate Anti- IL-1β-Induced Inflammation in Immature Enterocytes H4 Cells

To further investigate if butyrate anti IL-1β-induced inflammation was in part regulated by tight junction and mucin signaling pathways in H4 cells, an inhibitor of mucin (Tal) was used. The results showed that butyrate lost some of the anti-inflammatory effect with IL-1β-induced IL-8 secretion in H4 cells, suggesting that mucus is partially responsible for butyrate-mediated suppression of the inflammatory response in H4 cells (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Mucin inhibitor partially inhibited the anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate in H4 cells. H4 cells were pretreated with the mucin inhibitor Talniflumate before butyrate treatment then exposed to human IL-1β. Supernatants were collected and stored for IL8 ELISA analysis. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

These studies for the first time examine the effect of the short-chain fatty acid butyrate on the immature human intestine in vitro and partially confirmed their results in vivo in the newborn mouse intestine since whole intestinal homogenates were used for gene extraction. we have previously shown that premature newborns favor increased intestinal inflammation over immune homeostasis (10, 19). This is in large part the basis for the devastating intestinal emergency, necrotizing enterocolitis (22). As a laboratory, we have tried to define the mechanism for excessive inflammation in the premature infant leading to NEC. This study is an attempt to define the molecular basis involved in excessive inflammation and to begin to determine ways that it can be prevented. Accordingly, we used transcription profiling confirmed by qRT-PCR to determine the role of a short-chain fatty acid butyrate in reducing excessive inflammation in the immature intestine. These studies have not been done before in immature human intestine.

The intestinal epithelial barrier selectively regulates epithelial permeability to luminal bacteria and antigens. Abundant evidence indicates that an intact and healthy intestinal barrier is necessary for optimal health (21, 31). The disruption of the intestinal barrier contributes to the development of severe intestinal inflammation (11, 23). Indeed, multiple inflammatory cytokines have been shown to disrupt epithelial tight junctions and barrier integrity (3). The interleukins TNFα and interferon-γ (IFNγ) are known to increase epithelial cell permeability through impairment of tight junction assembly and actin cytoskeletal structure (9, 26, 40).

As the first barrier between the body and external contaminants, the intestinal mucosa has four principal interrelated functional barriers: a mechanical barrier, a chemical barrier, an immune barrier, and a biological barrier. Tight junction (TJ) proteins and intestinal epithelial cells constitute the mechanical barrier, and the intestinal mucus as well as symbiotic microbial communities constitute the gastrointestinal chemical barrier (1, 2). TJ proteins maintain adjacent epithelial cells at the apical side of the luminal membrane and anchor transmembrane proteins (claudins and occludin) to intracellular actin cytoskeleton (37). They play a crucial role in the regulation of paracellular permeability and maintenance of epithelium integrity (16, 37, 39).

Mucins are considered a principal part of the innate immune response (4). Over the years, mucins and their glycans have been suggested to have direct immunological effects by binding to the numerous lectin-like proteins found on immune cells. The surface of the mucin domains formed by the glycan arrangement is important for receptor binding. For example, select proteins are used to recruit immune cells to inflammatory sites (13). The importance of mucus in the small intestine is also illustrated in Muc2-deficient mice as these animals have an increased bacterial burden that drives increased epithelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and tumor development and increased production of antibacterial immune components (32, 34).

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are produced by bacterial fermentation, particularly of dietary fiber and carbohydrate in the large intestine. They have been found to exert profound influences on intestinal barrier function, the immune response, epithelial cell proliferation, and bacterial pathogenesis (17, 39). Among these SCFA, butyrate, a four-carbon fatty acid, has been tested as one of the therapeutic options for colonic inflammatory diseases (38). This was consistent with results that show that butyrate decreases intestinal permeability and enhances assembly of tight junctions in a Caco-2 cell model (8, 12). However, they were not previously tested in vivo with small intestine conditions (38). In the present study, we found that butyrate inhibited IL-1β- induced CX3XL1, CXCL5, and IL-6 gene expression (Table 1), indicating that butyrate could inhibit the inflammatory-induced by IL-1β stimulation in human small intestine H4 cells. Butyrate also has an anti-inflammatory effect in the newborn mouse intestine in vivo (Fig. 5).

In the present study, we found that butyrate increased the expression of claudin-3 and claudin-4 and restored its reduction in these proteins caused by IL-1β challenge (Table 2). Butyrate also increased tight junction-related gene expression levels in vivo (Fig. 4). Although these studies were done in whole intestinal homogenates, claudins are the principal structural and functional components of tight junctions, selectively preventing passage of luminal substances through paracellular routes (37). A decrease in protein expression of claudins is highly correlated with impaired intestinal barrier function (3, 28). Occludin is known to regulate the gating of tight junctions (3, 27, 29). Therefore, we could speculate that the protective effect of butyrate on the intestinal barrier against IL-1β damage may be partly explained by the increase in the expression of claudin and occludin proteins.

Furthermore, in the present study, we also found that butyrate regulated the mucin-related genes both in vitro and in vivo (Table 2 and Fig. 4). The increased epithelial barrier function in E12 cells was not manifested as increased expression of the intercellular junction protein zonula occludens 1 but as the mucus produced by goblet cells as indicated by lower expression of genes encoding for the gel-forming mucin (MUC2) at higher butyrate levels (5). In pigs, diet-induced alterations in large-intestinal SCFA production showed only a minor influence in parameters related to intestinal barrier function. It was only the mRNA abundance of MUC2 that was influenced by the diet-induced butyrate production (11), whereas other parameters measured (murin 2, zonula occludens 1, and occludin) were not influenced. Therefore, we also could speculate that the protective effect of butyrate on intestinal barrier against IL-1β damage may be partly explained by the increase in the expression of mucin proteins. To confirm our speculation that if butyrate anti IL-1β-induced inflammation was regulated by tight junction and mucin signaling pathways in H4 cells, an inhibitor of mucin was used. These results showed that mucin is in part necessary for butyrate-mediated suppression of the inflammatory response in H4 cells (Fig. 6).

In summary, we have demonstrated that butyrate inhibited IL-1β-induced inflammation in vitro and partially in vivo by promoting tight junction (especially claudins and occludin) and mucin expression levels. Results obtained in the present study agree with the reported studies in adult intestine. It has been reported that in human subjects with metabolic syndrome, an increased colonic expression of MUC2 and tight junction protein occludin was observed following diet-induced increase in SCFA, specifically butyrate, production (24). These latter results are in accordance with results from a pig study encompassing arabinoxylan (25) and from rodent and pig studies concerning resistant starch (7, 15).

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant P01-DK-033506 (to W. A. Walker), the Family Larsson-Rosenquist Foundation (to W. A. Walker), and Beth Israel/Deaconess Medical Center Award (to W. A. Walker).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.W. conceived and designed research; Y.G., B.D., W.Z., and N.Z. performed experiments; Y.G. and D.M. analyzed data; D.M. and W.W. interpreted results of experiments; Y.G. and D.M. prepared figures; Y.G., D.M., and W.W. drafted manuscript; W.W. edited and revised manuscript; W.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Katharine Grant for typing and editing the manuscript and Wuyang Hung and Ky Young Cho for helping to perform some experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahdieh M, Vandenbos T, Youakim A. Lung epithelial barrier function and wound healing are decreased by IL-4 and IL-13 and enhanced by IFN-γ. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C2029–C2038, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Dokladny K, Ma TY. Mechanism of IL-1β-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J Immunol 180: 5653–5661, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrieta MC, Bistritz L, Meddings JB. Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut 55: 1512–1520, 2006. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashida H, Ogawa M, Kim M, Mimuro H, Sasakawa C. Bacteria and host interactions in the gut epithelial barrier. Nat Chem Biol 8: 36–45, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balda MS, Matter K. Tight junctions at a glance. J Cell Sci 121: 3677–3682, 2008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedford A, Gong J. Implications of butyrate and its derivatives for gut health and animal production. Anim Nutr 4: 151–159, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Mao X, He J, Yu B, Huang Z, Yu J, Zheng P, Chen D. Dietary fibre affects intestinal mucosal barrier function and regulates intestinal bacteria in weaning piglets. Br J Nutr 110: 1837–1848, 2013. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira TM, Leonel AJ, Melo MA, Santos RRG, Cara DC, Cardoso VN, Correia MI, Alvarez-Leite JI. Oral supplementation of butyrate reduces mucositis and intestinal permeability associated with 5-Fluorouracil administration. Lipids 47: 669–678, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11745-012-3680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Förster C. Tight junctions and the modulation of barrier function in disease. Histochem Cell Biol 130: 55–70, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganguli K, Meng D, Rautava S, Lu L, Walker WA, Nanthakumar N. Probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating enterocyte genes that regulate innate immune-mediated inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304: G132–G141, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00142.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groschwitz KR, Hogan SP. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124: 3–20, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilloteau P, Martin L, Eeckhaut V, Ducatelle R, Zabielski R, Van Immerseel F. From the gut to the peripheral tissues: the multiple effects of butyrate. Nutr Res Rev 23: 366–384, 2010. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell 84: 345–357, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hackam DJ, Sodhi CP. Toll-like receptor–mediated intestinal inflammatory imbalance in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 6: P229–238.e1, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hald S. Effect of Dietary Fibres on Gut Microbiota, Faecal Short-chain Fatty Acids and Intestinal Inflammation in the Metabolic Syndrome (dissertation). Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus Universitet, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer AM, Morris NL, Earley ZM, Choudhry MA. The first line of defense: the effects of alcohol on post-burn intestinal barrier, immune cells, and microbiome. Alcohol Res 37: 209–222, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15064–15069, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin HC, Su BH, Chen AC, Lin TW, Tsai CH, Yeh TF, Oh W. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 115: 1–4, 2005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng D, Zhu W, Ganguli K, Shi HN, Walker WA. Anti-inflammatory effects of Bifidobacterium longum subsp infantis secretions on fetal human enterocytes are mediated by TLR-4 receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 311: G744–G753, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00090.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng D, Zhu W, Shi HN, Lu L, Wijendran V, Xu W, Walker WA. Toll-like receptor-4 in human and mouse colonic epithelium is developmentally regulated: a possible role in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 77: 416–424, 2015. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita T, Tanabe H, Sugiyama K, Kasaoka S, Kiriyama S. Dietary resistant starch alters the characteristics of colonic mucosa and exerts a protective effect on trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68: 2155–2164, 2004. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 364: 255–264, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neunlist M, Van Landeghem L, Mahé MM, Derkinderen P, des Varannes SB, Rolli-Derkinderen M. The digestive neuronal-glial-epithelial unit: a new actor in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 90–100, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen DS, Jensen BB, Theil PK, Nielsen TS, Knudsen KE, Purup S. Effect of butyrate and fermentation products on epithelial integrity in a mucus-secreting human colon cell line. J Funct Foods 40: 9–17, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen TS, Theil PK, Purup S, Nørskov NP, Bach Knudsen KE. Effects of resistant starch and arabinoxylan on parameters related to large intestinal and metabolic health in pigs fed fat-rich diets. J Agric Food Chem 63: 10418–10430, 2015. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald IP. Role of intestinal epithelial cells in the innate immune defence of the pig intestine. Vet Res 37: 359–368, 2006. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng L, He Z, Chen W, Holzman IR, Lin J. Effects of butyrate on intestinal barrier function in a Caco-2 cell monolayer model of intestinal barrier. Pediatr Res 61: 37–41, 2007. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250014.92242.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng L, Li ZR, Green RS, Holzman IR, Lin J. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Nutr 139: 1619–1625, 2009. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinton P, Braicu C, Nougayrede JP, Laffitte J, Taranu I, Oswald IP. Deoxynivalenol impairs porcine intestinal barrier function and decreases the protein expression of claudin-4 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. J Nutr 140: 1956–1962, 2010. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Repa A, Thanhaeuser M, Endress D, Weber M, Kreissl A, Binder C, Berger A, Haiden N. Probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum) prevent NEC in VLBW infants fed breast milk but not formula. Pediatr Res 77: 381–388, 2015. [Erratum in Pediatr Res 77: 381–388, 2016]. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez-Cabezas ME, Camuesco D, Arribas B, Garrido-Mesa N, Comalada M, Bailón E, Cueto-Sola M, Utrilla P, Guerra-Hernández E, Pérez-Roca C, Gálvez J, Zarzuelo A. The combination of fructooligosaccharides and resistant starch shows prebiotic additive effects in rats. Clin Nutr 29: 832–839, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen SD. Ligands for L-selectin: homing, inflammation, and beyond. Annu Rev Immunol 22: 129–156, 2004. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.090501.080131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanderson IR, Ezzell RM, Kedinger M, Erlanger M, Xu Z-X, Pringault E, Leon-Robine S, Louvard D, Walker WA. Human fetal enterocytes in vitro: modulation of the phenotype by extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 7717–7722, 1996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schierack P, Nordhoff M, Pollmann M, Weyrauch KD, Amasheh S, Lodemann U, Jores J, Tachu B, Kleta S, Blikslager A, Tedin K, Wieler LH. Characterization of a porcine intestinal epithelial cell line for in vitro studies of microbial pathogenesis in swine. Histochem Cell Biol 125: 293–305, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sela DA, Chapman J, Adeuya A, Kim JH, Chen F, Whitehead TR, Lapidus A, Rokhsar DS, Lebrilla CB, German JB, Price NP, Richardson PM, Mills DA. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18964–18969, 2008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809584105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol 121: 91–119 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800100-4.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 799–809, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velcich A, Yang W, Heyer J, Fragale A, Nicholas C, Viani S, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Yang K, Augenlicht L. Colorectal cancer in mice genetically deficient in the mucin Muc2. Science 295: 1726–1729, 2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1069094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wan ML, Turner PC, Allen KJ, El-Nezami H. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG modulates intestinal mucosal barrier and inflammation in mice following combined dietary exposure to deoxynivalenol and zearalenone. J Funct Foods 22: 34–43, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F, Graham WV, Wang Y, Witkowski ED, Schwarz BT, Turner JR. Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol 166: 409–419, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62264-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng N, Gao Y, Zhu W, Meng D, Walker WA. Short chain fatty acids produced by colonizing intestinal commensal bacterial interaction with expressed breast milk are anti-inflammatory in human immature enterocytes. PLoS One 15: e0229283, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]