Abstract

This study investigated children’s and adolescents’ predictions regarding intergroup inclusion in contexts where peers differed on two dimensions of group membership: race and wealth. African American and European American participants (N = 153, aged 8-14 years old, Mage = 11.46 years) made predictions about whether after-school clubs would prefer to include a peer based on race or wealth, and reported what they personally thought should happen. Between late childhood and early adolescence, European American participants increasingly expected that after-school clubs would include a same-wealth peer (even when this peer was of a different race) whereas African American participants increasingly expected that the after-school clubs would include a same-race peer (even when this peer was of a different level of wealth). Both European American and African American participants themselves thought that the clubs should include a same-wealth peer over a same-race peer, and with age, were increasingly likely to reference perceived comfort when explaining their decision. Future studies on the development of racial preferences will benefit from including wealth status information given that, with age, perceived comfort was associated with same-wealth rather than same-race status.

Keywords: Prejudice, intergroup attitudes, racial attitudes, wealth status, social exclusion, peers

Inclusion and exclusion from social groups are highly salient experiences in childhood and adolescence. Individuals who are repeatedly excluded by peers are at risk for a host of negative outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal (Marks et al., 2015; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Social exclusion on the basis of group membership such as gender, race, socioeconomic status, religion, or sexual orientation is particularly detrimental (Møller & Tenenbaum, 2011). This form of exclusion – referred to as intergroup exclusion – is related to prejudice in childhood (Pauker et al., 2016; Rutland et al., 2010). Developmental research has examined how children evaluate intergroup exclusion decisions, revealing the reasoning, attitudes, and beliefs that bear on intergroup peer interactions and relationships (Burkholder, D’Esterre et al., 2019; Elenbaas & Killen, 2016a).

Research has demonstrated that children and adolescents often view intentional intergroup exclusion as unfair and wrong (Killen et al., 2013; McGuire et al., 2015; Rutland et al., 2017). In contrast, intergroup inclusion is often viewed as legitimate, especially because these decisions include both inclusion and exclusion. The potential prejudice or discrimination that results with intergroup inclusion is not always readily apparent to children and adolescents (Burkholder et al., 2020; Mulvey, 2016). For example, when an after-school club selectively includes new members who are boys and does not include any girls then gender-based exclusion has implicitly occurred. Thus, understanding how children evaluate intergroup inclusion provides an important window into the origins of prejudice in childhood. The aim of this study was to examine children’s and adolescents’ predictions and preferences regarding decisions to include a peer into a club when the individuals involved differed on two dimensions of group membership: race and wealth.

Inclusion in Childhood and Adolescence

Overall, children evaluate selective inclusion on the basis of group membership (e.g., a group of boys includes another boy rather than a girl) as more acceptable than intentional exclusion on the basis of group membership (e.g., a group of boys refuses to include a girl with no legitimate reason) (Mulvey, 2016). One explanation for this pattern is that children view selective inclusion as less likely to result in negative outcomes than direct exclusion (Burkholder et al., 2020). Moreover, in late childhood and early adolescence, children increasingly condone selective ingroup inclusion (a group deciding to include someone of the same background) due to a perceived “lack of shared interests” with outgroup members (Hitti & Killen, 2015; Nesdale & Lawson, 2011; Stark & Flache, 2012). Moreover, adolescents are likely to explain discomfort with interracial interactions in terms of racial stereotypes, and particularly when they attend low-diversity schools (Killen et al., 2010), suggesting that a sense of discomfort may play a role in biased peer group choices during this developmental period.

While the acceptability of selective ingroup inclusion and preference for same-race friendships have been well documented, particularly among ethnic majority status individuals (Cooley et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2017; Thijs, 2017), much less research has examined ethnic minority status children’s predictions and evaluations of inclusion. One exception is a study with 9- to 14-year old participants in which African American children expected interracial and same-race exclusion to be equally likely but evaluated all types of exclusion more negatively than did European American children (Cooley et al., 2019).

Belonging to Multiple Groups

Intergroup inclusion choices are not one-dimensional, because individuals belong to many social groups simultaneously (Hall et al., 2016; Santos & Toomey, 2018). For example, a child may be African American, a girl, and Muslim. To date, little research has investigated children’s thinking about inclusion of individuals who share or do not share multiple social group memberships with their peers, and thus little is known about how children weigh multiple group memberships when predicting and evaluating instances of peer inclusion. Understanding which forms of group membership children consider most relevant to inclusion decisions will provide important evidence for how children make complex social decisions in their everyday lives, and may point to how certain group memberships place children at greater or lesser risk for subtle peer exclusion.

The aim of this study was to examine developing evaluations of peer groups at the intersection of two social group memberships: race and wealth. By late childhood (8-10 years of age), children distinguish between peers on the basis of wealth, use labels like “rich”, “poor”, and “middle class”, and begin to hold stereotypes about wealth groups (Mistry et al., 2015; Sigelman, 2012). Interestingly, late childhood is also the time when interracial friendships begin to decline (Aboud et al., 2003) and some children begin to view interracial exclusion as acceptable (Cooley et al., 2019; Killen et al., 2007). How these multiple group memberships impact children’s social decisions has recently been discussed as an important topic for empirical investigation (Burkholder, D’Esterre et al., 2019; Rogers, 2019; Rogers et al., 2015).

Race and Wealth in Children’s Inclusion Decisions

In the U.S., children and adolescents alike make associations regarding racial and wealth group memberships (Elenbaas & Killen, 2016b; Olson et al., 2012; Shutts et al., 2016). Specifically, U.S. children of multiple racial and socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to associate African Americans with the low end of the wealth spectrum and European Americans with the high end of the wealth spectrum (Elenbaas & Killen, 2016b; Shutts et al., 2016). To date, the data also suggest that while children readily reject the use of explicit racial stereotypes as unfair (Killen & Rutland, 2011), they often explicitly endorse wealth-based stereotypes (Brown, 2017). Notably, children often explicitly endorse stereotypes that poor individuals are lazy or unskilled and that rich individuals are hard-working and competent (Brown, 2017; Leahy, 1981; Mistry et al., 2015; Sigelman, 2012, 2013; Woods et al., 2005). Because children associate race with wealth, children’s wealth stereotypes may exacerbate their tendency to refrain from interracial peer inclusion.

What needs to be investigated is whether children predict and prefer same-wealth friendships even when these same-wealth peers come from different racial backgrounds (and vice versa, whether children predict and prefer same-race friendships when the peers come from different wealth backgrounds). Perhaps expectations that different race peers lack shared interests are exacerbated by assumptions that different race peers also come from different wealth backgrounds, falsely equating the lack of similarities across two indices of group difference rather than one (Hitti & Killen, 2015; Killen et al., 2010; Stark & Flache, 2012). Whether these preferences and expectations are endorsed by children from different racial backgrounds, however, has not been investigated. In fact, no research, to date, has examined children’s predictions or preferences about peer inclusion based on race and wealth group memberships together.

Present Study

To address these questions, the present study investigated children’s and adolescents’ predictions and evaluations about after-school clubs’ decisions to include a peer when both race and wealth were salient intergroup factors. The goals of the present study were to investigate whether children prioritize race or wealth in intergroup inclusion settings, and whether age-related and group-related influences are shown for children’s predictions, preferences, and reasoning in this context.

The study included children and adolescents between the ages of 8 – 14 years, from middle- to upper-middle income backgrounds. This age range was selected for studying age-related patterns regarding interracial and inter-wealth inclusion because by late childhood, children attend to their peers’ wealth status and racial group membership (Arsenio, 2015; Mistry et al., 2015; Elenbaas & Killen, 2016b). Further, with age, children become better able to weigh multiple, competing aspects simultaneously when making decisions in social contexts (Killen & Rutland, 2015; Mulvey, 2016; Smetana, 2011). Given the complex number of factors in this study, and the opportunity to include a sample reflecting two racial groups, socioeconomic background was controlled (middle-to upper-middle income participants). Participants were African American and European American by parent report, similar to previous research in the U.S. cultural and historical context which has emphasized understanding how race and wealth jointly shape social experiences for these particular groups.

The experimental task included a vignette in which after-school clubs had the opportunity to include peers (target characters) who matched the pre-existing club members on either their racial group membership or their wealth group membership. Children made predictions about whom the clubs would include, reported their own preferences for inclusion, and provided reasoning for their choices.

Theoretical model.

The research aims, hypotheses, and design were informed by the Social Reasoning Developmental (SRD) Model (Killen & Rutland, 2011). The SRD Model draws on theories and research from developmental psychology (social domain theory) and social psychology (social identity theory) to frame children’s intergroup exclusion and inclusion decisions as grounded in reasoning about social norms, morality, and group identity (social domain theory: Smetana et al., 2014; Turiel, 2002; social identity theory: Nesdale, 2004; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). The SRD framework proposes that children do not uniformly endorse ingroup inclusion in all contexts. Instead, children take a variety of different concerns into account when deciding how to construct their intergroup peer relationships. This includes moral concerns such as priority for fair and equal treatment of diverse others, as well as group concerns such as group functioning, group identity, and stereotypic expectations about social roles and status.

When children reject intergroup exclusion or support intergroup inclusion, they often use moral reasoning about fairness (Cooley et al., 2019). Further, when they condone or endorse inclusion and exclusion, reasons based on group identity, group functioning or stereotypes are often invoked (Burkholder et al., 2019). With age and increased social experience, children are more likely to consider multiple factors (such as both race and wealth status) when making predictions about social interactions (Mulvey, 2016).

Hypotheses.

Regarding children’s predictions of inclusion, we had two main hypotheses. First (H1), we hypothesized that, overall, children would predict that clubs would prioritize wealth over race when deciding whom to include, as children show an increasing awareness of wealth during this developmental period which may factor into their social decisions (Brown, 2017; Mistry et al., 2015). Second (H2), we hypothesized that between late childhood and early adolescence, European American children would increasingly predict that clubs would prioritize wealth over race, while African American children would increasingly predict that clubs would prioritize race over wealth. This expectation was based on previous research that suggests that, with age, African American’s specific experiences with racially motivated exclusion and discrimination provide a more realistic view of possible negative interracial interactions, while European American children may paint a more optimistic view (Elenbaas & Killen, 2016b; Seaton et al., 2012).

Regarding children’s own preferences for inclusion, we had two main hypotheses. First (H3), we predicted that, overall, children would prioritize wealth over race when deciding whom to include, as wealth may be seen as an avenue for shared interests and experiences, a factor children weigh when predicting and evaluating inclusion choices (Hitti & Killen, 2015). Second (H4), we predicted that this pattern would increase between late childhood and early adolescence, as shared interests in peer groups become more important in early adolescence (Killen & Rutland, 2015).

Finally, regarding children’s reasoning for their selections, we had two main hypotheses. First (H5), we hypothesized that, with age, children would increasingly justify their predictions and preferences by referencing a sense of comfort with ingroup members (Killen et al., 2010); and (H6) children would reference the benefits of diversity when predicting a focus on wealth rather than race (Rutland et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants included 153 children between 8 and 14 years of age (MAge = 11.46 years, SDAge = 1.72; 58% female) recruited from the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. As identified by their parents, approximately half of the participants were African American (n = 80; MAge = 11.25 years, SDAge = 1.76) and half of the participants were European American (n = 73; MAge = 11.69 years, SDAge = 1.65). Both African American and European American participants were recruited from the same metropolitan region and from similar, middle-income communities during 2016-2017.

By parent report, both African American families and European American families, on average, had household incomes in the middle-income range for the region where these data were collected (average reported annual household income was between $150,00 and $180,000; MIncome = 6.01, SDIncome = 2.061). African American participants’ annual household income averaged between $150,000 and $180,000 (MAA = 6.61, SDAA = 1.776) and European American participants’ annual household income averaged between $120,000 and $150,000 (MEA = 5.39, SDEA = 2.137), with 75% of the sample reporting a household income of $90,000 or more. The median annual income for a family of four in the region of data collection in 2017 was $110,300, while the national median for the U.S. was $61,372 (United States Census Bureau, 2018). African American families reported higher incomes on average than European American families, F(1,93) = 4.75, p = 0.03. There were no between-group differences in mothers’ or fathers’ educational attainment (ps > .05); both African American and European American parents reported attaining a bachelor’s degree, on average.

Power analyses.

Sample size was determined with a priori power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), for the binomial logistic regression presented in the Data Analysis Plan below. Based on previous literature and expecting medium effects (an odds ratio of 2.80) with α at .05 and power at .80, a minimum of approximately 151 participants would be necessary to test our hypotheses.

Procedure

This study was approved by the [BLINDED] institutional review board (Social categorization and peer group relationships: #872815-4). Parental consent and verbal assent were obtained for all participants. Participants completed individual interviews with trained experimenters who were blind to the study hypotheses. Using brightly colored vignette illustrations displayed on a laptop screen, the interview lasted approximately 20 minutes.

Measures

Participants were first introduced to clubs at a fictional school: “In this school there are two clubs. Clubs are an important part of the school. Because all of the clubs have meetings at the same time, children can only belong to one club.” The clubs were represented by showing photographs of individual children (3 boys and 3 girls) for each club who shared the same racial group membership (African American or European American) and wealth group membership (low or high). The race and wealth of the clubs varied between subjects, such that approximately half of the participants (n = 81) viewed a high wealth European American club and a low wealth African American club while approximately half (n = 72) viewed a high wealth African American club and a low wealth European American club.

Race was depicted through photographs of children that varied by skin tone and hair type. Similar to prior research (Elenbaas & Killen, 2016b; Hurst et al., 2017), wealth was depicted through images of monetary resources (a large stack of dollar bills or only a few dollar bills), and the high wealth club was associated with photographs of a very large house, a new sports car, and a photograph depicting a beach vacation while the low wealth club was associated with a very small house, an old car, and a photograph of a swing set in a backyard. The stimuli chosen for representing high and low wealth far exceeded the depiction of housing and cars in the region where the participants were sampled for this study (e.g., the high-wealth houses and cars were beyond the means of the income levels of the sample and the low-wealth houses and cars were much lower).

Next participants were told, “Remember, at this school every kid must belong to only one club. This year, two new kids came to the school. They can join either [Club X] or [Club Y].” The “new kids” (target characters) varied in race and wealth such that each character matched Club X on one attribute (e.g., race) and Club Y on the other attribute (e.g., wealth).

Predictions.

For both after-school clubs, participants answered the same prompt: “[Club X/Y] can choose [Target Character 1] or [Target Character 2] to be in their club. Who do you think they will pick?”. The clubs’ and target characters’ racial and wealth group memberships varied by condition. For each item, participants’ responses were recorded as prediction of racial ingroup inclusion (0) or prediction of wealth ingroup inclusion (1).

Preferences.

Next participants were asked to choose: “Which club is the best for [Target Character 1], and which club is the best for [Target Character 2]?” Participants were reminded that each character could only join one club and each club only had one open spot. Responses were recorded as preference for racial ingroup inclusion (0) or preference for wealth ingroup inclusion (1).

Reasoning.

Children’s reasoning for both their predictions and preferences was coded into one of three mutually exclusive conceptual categories based on the SRD model (Rutland et al., 2010) and pilot testing. Coding categories included: 1) Perceptions of Ingroup Similarity/Outgroup Dissimilarity (e.g., “Cause they do have similar things in common”; “Because they have more money and he has more money too”); 2) Perceptions of Ingroup Comfort/Outgroup Discomfort (e.g., “She might feel more comfortable with people who are her same skin color”); and 3) Benefits of Diversity (e.g., “That way he can see what it’s like to live the way that they do”; “Maybe she can give the club some of her money and then they can all be better”). Justifications that did not reference any of the above categories (e.g., “I don’t know”) were coded as Other. Two research assistants blind to the hypotheses of the study conducted the coding. On the basis of 30% of the interviews (n = 46), Cohen’s κ = .84 for interrater reliability was achieved.

Data Analysis Plan

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 27. Children’s predictions, preferences, and reasoning did not correlate significantly with gender or with approximate annual family income (ps > .05); as these variables were not related to hypotheses, they were not included in subsequent analyses (see Table 1 for correlations among all study variables).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables and Demographics

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Participant Age (8-14 years) | |||||||

| 2. Participant Race | .130 | ||||||

| 3. Participant Gender | −.011 | −.092 | |||||

| 4. Approximate Annual Family Income | −.159 | −.312** | .119 | ||||

| 5. Club Race (Condition) | .090 | −.035 | .030 | .029 | |||

| 6. Inclusion Prediction: High Wealth Club | −.032 | .012 | −.093 | −.057 | −.062 | ||

| 7. Inclusion Prediction: Low Wealth Club | −.110 | .004 | −.119 | −.050 | .057 | .589** | |

| 8. Participant Inclusion Preference | .147 | −.072 | .047 | .094 | .013 | .167* | .170* |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

For participant race: African American = 1, European American = 2. For participant gender: Girl =1, Boy = 2. For inclusion predictions and preferences, Same Race = 0, Same Wealth = 1.

To test our hypotheses that children would predict that clubs would prioritize wealth over race when deciding whom to include (H1), and with age European American children would increasingly predict that clubs would prioritize wealth over race while African American children would increasingly predict that clubs would prioritize race over wealth (H2), we ran a generalized linear mixed model with a binomial probability distribution and logit link function, regressing children’s predictions (1 = wealth match, 0 = race match) on the within-subjects variables club wealth (high wealth, low wealth), the between-subjects variables participant age (8 to 14 years), participant race (African American, European American), and club race (African American, European American), and the interactions of participant age and participant race, participant race and club race, and participant race and inclusion prediction.

To test our hypotheses that children would prioritize wealth over race when deciding whom to include (H3), and that this pattern would increase between late childhood and early adolescence (H4), we ran a binomial logistic regression with follow up z tests with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. The model included the effects of participant age (from 8 to 14 years), participant race (African American, European American), the interaction between participant age and participant race, and club race (African American, European American) on children’s inclusion preferences.

To test our hypotheses that with age, children would increasingly justify their perceptions by referencing a sense of comfort with ingroup members (H5) and that children would reference the benefits of diversity when predicting a focus on wealth rather than race (H6), we ran three multinomial logistic regression models for children’s predictions of peer inclusion and their own inclusion preferences, with follow up z tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. We modeled the effects of participant response (race match, wealth match), participant age, participant race (African American, European American), and club race (African American, European American) on reasoning across three conceptual categories (similarity, comfort, and benefits of diversity) with similarity as the reference category.

Results

Predictions of Inclusion

The model testing H1 and H2 was significant, likelihood ratio χ2 (7, N = 306) = 55.117, p < .001. The effect of club wealth was significant, F(1,298) = 4.35, p = .038, β = 1.484, 95% CI [−.138, .984]. Overall, participants predicted that clubs would prefer to include the peer who shared their wealth group membership (but not their racial group membership) over the peer who shared their racial group membership (but not their wealth group membership), supporting H1. However, children were more likely to predict same-wealth inclusion for the high wealth club than the low wealth club. Specifically, 82% (n = 125) of participants (81% of African Americans and 82% of European Americans) predicted that the high wealth club would include the same-wealth peer over the same-race peer; ps < .001 relative to chance. Additionally, 75% (n = 115) of participants (75% of African Americans and 75% of European Americans) predicted that the low wealth club would include the same-wealth peer over the same-race peer; ps < .001 relative to chance.

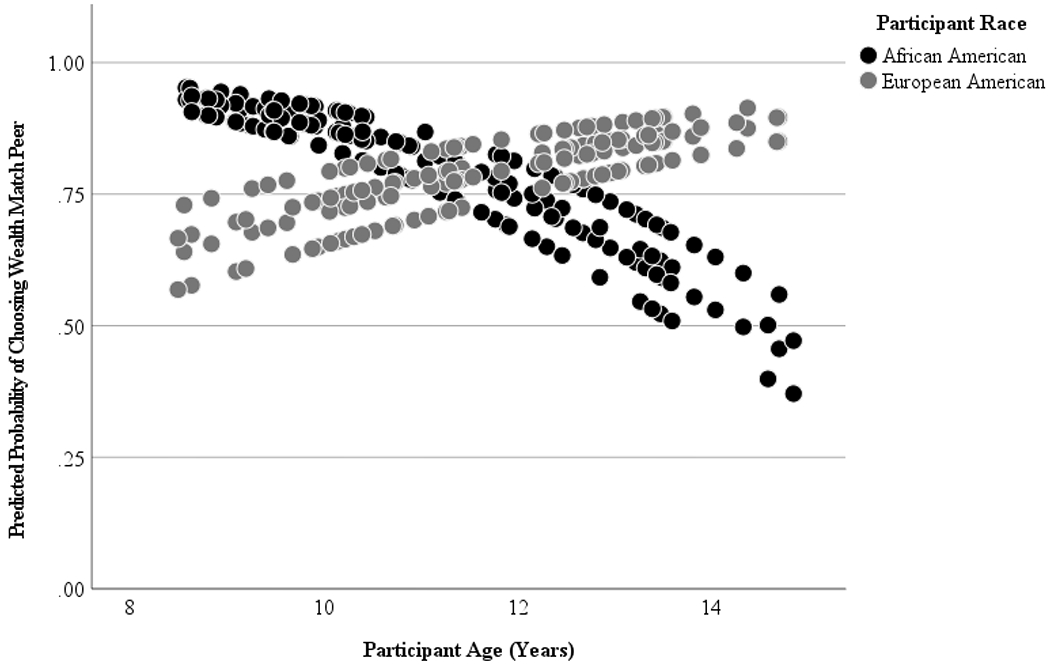

The effect of participant race was also significant, F(1, 298) = 9.47, p = .002, β = 8.963, 95% CI [3.38, 14.54]. Most importantly, in line with H2, there was a significant interaction between participant age and participant race, F(1,298) = 9.794, p = .002, β = −.495, 95% CI [−.821, −.169]. As illustrated in Figure 1, with age, European American children were increasingly likely to expect the high wealth club to include the target character who matched them in wealth while African American children were increasingly likely to expect the high wealth club to include the target character who matched them in race.

Figure 1. Children’s Expectations for Clubs’ Inclusion Choices By Participant Age and Race.

Note. Circles indicate predicted probabilities of choosing the wealth match peer (1) over the race match peer (0) by participant age and race, where black circles represent African American participants and grey circles represent European American participants.

The effects of participant age (F(1,298) = 1.246, p = .265) and club race (F(1,298) = .616, p = .433) were not significant, and interactions between participant race and club race (F(1,298) = 1.735, p = .189), and participant race and club wealth (F(1,298) = .000, p = .983), were also not significant.

Participant Preference for Inclusion

In line with H3, 76% (n = 116) of participants (79% of African Americans and 73% of European Americans), indicated that the “best” club for each target character was the club that matched them in wealth group membership (rather than racial group membership); ps < .001 relative to chance.

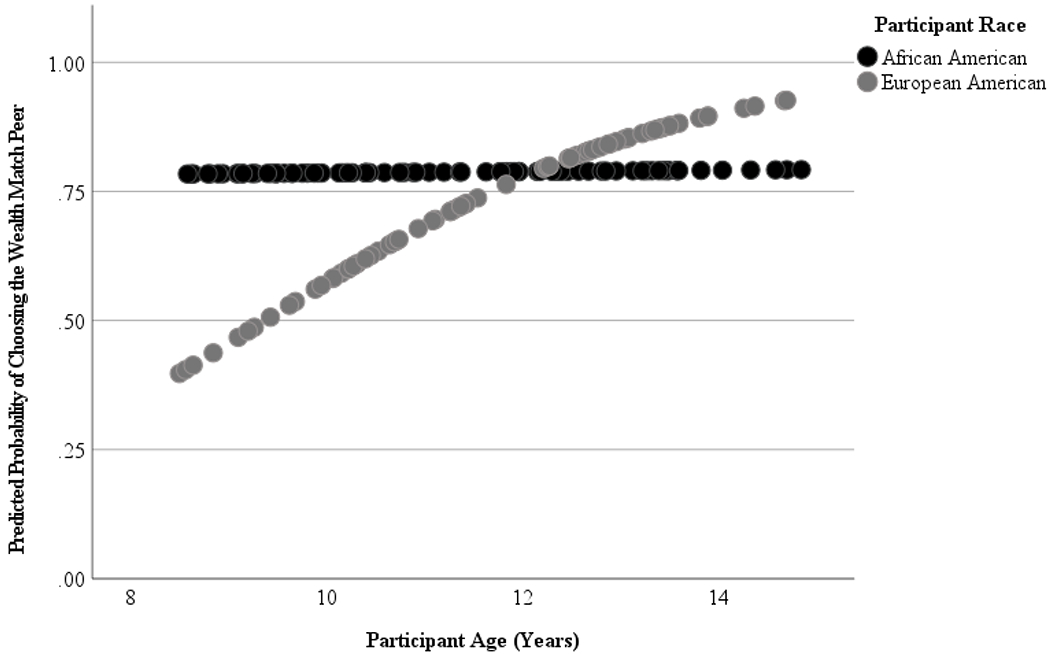

Participant age, participant race and the interaction between the two variables were entered in the first step, resulting in a significant improvement in model fit, χ2(3) = 8.686, p = .034, Nagelkerke R2 = .082. The effect for participant race was significant, β = −5.685, t(153) = 4.434, p = .035, Exp(B) = .003, 95% CI [.000, .675] and there was a significant interaction between participant age and participant race, β = .468, t(153) = 9.152, p = .050, Exp(B) = 1.597, 95% CI [1.001, 2.549]. As illustrated in Figure 2, with age, European American children were more likely to advocate for a match on wealth group membership while African American children’s preferences remained stable with age (Figure 2), providing partial support for H4.

Figure 2. Children’s Own Preferences for Inclusion by Participant Age and Race.

Note. Circles indicate predicted probabilities of choosing the wealth match peer (1) over the race match peer (0) by participant age and race, where black circles represent African American participants and grey circles represent European American participants.

There was no significant effect for participant age (β = −.460, t(153) = 1.629, p = .202) or club race (β = .054, t(153) = .019, p = .891).

Children’s Justifications

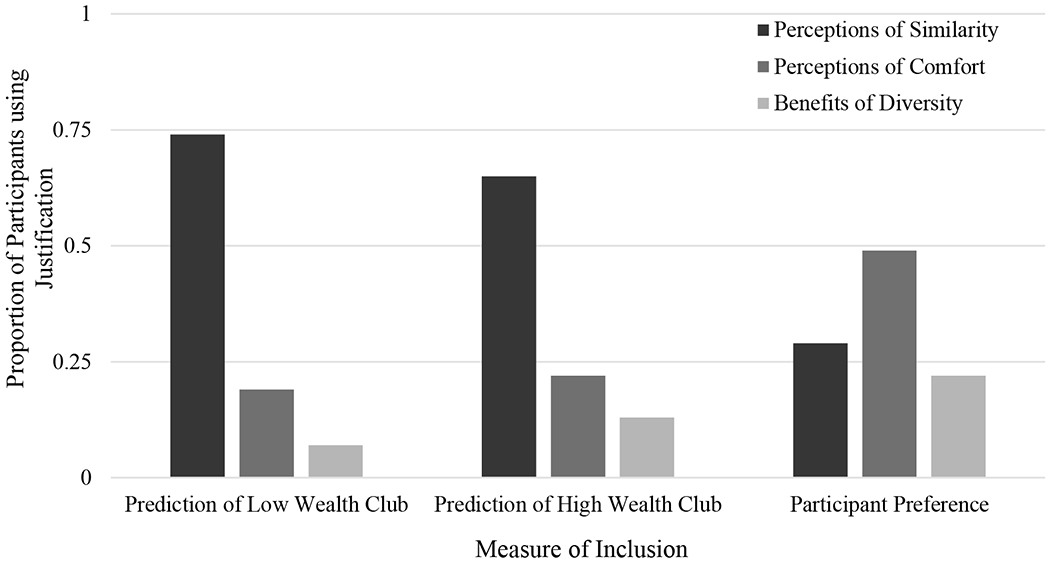

Figure 3 presents children’s reasoning for each question. The proportion of justifications that participants used for their judgments are represented for the three distinct conceptual categories were used to code responses (and “Other”): “Perceptions of Similarity,” “Perceptions of Comfort,” “Benefits of Diversity.” Less than 4% of responses were classified as “other” and dropped from analyses. Codes were assigned by two reliable coders who were blind to the hypotheses of the study, were mutually exclusive, and were based on the SRD model (Rutland et al., 2010) and pilot data.

Figure 3. Children’s Justifications for their Predictions and Preference for Inclusion by Low and High Wealth Clubs.

Note. N = 148 for low wealth club inclusion prediction; N = 147 for high wealth club inclusion prediction; N = 150 for participant inclusion preference. Codes were mutually exclusive and proportions total to 1 within each measure of inclusion.

Reasoning about predictions of inclusion for the high wealth club.

Addition of the predictors to the model led to a significant improvement of model fit, LR χ2(8) = 49.884, Nagelkerke R2 = .372, p < .001. The effect of participant age was significant, χ2(2) = 12.013, p = .002. Specifically, increasing age was associated with increasing justifications about comfort, β = .425, χ2(1) = 8.512, p = .004, Exp(B) = 1.530.

The effect of participant response was also significant, χ2(2) = 28.748, p < .001. Contrary to H6, participants were more likely to reference the benefits of diversity when predicting that the club would select the race match peer and more likely to reference similarity when predicting that the club would select the wealth match peer, β = 4.187, χ2(1) = 19.109, p < .001, Exp(B) = 65.824.

The effect of club race was significant, χ2(2) = 6.159, p < .046, but follow up tests did not reveal any significant differences. Participant race did not significantly influence participants’ justifications, χ2(2) = 4.751, p < .093.

Reasoning about predictions of inclusion for the low wealth club.

Addition of the predictors to the model led to a significant improvement of model fit, LR χ2(8) = 72.263, Nagelkerke R2 = .469, p < .001. The effect of participant age was significant, χ2(2) = 6.594, p < .037. Specifically, increasing age was associated with increasing justifications about comfort, β = .300, χ2(1) = 5.399, p = .020, Exp(B) = 1.350.

The effect of participant response was significant, χ2(2) = 55.225, p < .001. Again contrary to H6, participants were more likely to reference the benefits of diversity when predicting that the club would select the race match peer, and more likely to reference similarity when predicting that the club would select the wealth match peer, β = 5.341, χ2(1) = 21.898, p < .001, Exp(B) = 208.691.

The effect of club race was significant, χ2(2) = 8.541, p = .014. Participants were more likely to reference the benefits of diversity when the low wealth club was European American than when the low wealth group was African American, regardless of participants’ own predictions, β = 2.246, χ2(1) = 6.504, p = .011, Exp(B) = 9.449. Participant race did not significantly influence participants’ justifications, χ2(2) = 1.864, p = .394.

Reasoning for participants’ own inclusion preferences.

Addition of the predictors to the model led to a significant improvement of model fit, LR χ2(8) = 91.258, Nagelkerke R2 = .520, p < .001. The effect of participant age was significant, χ2(2) = 8.380, p = .015. Supporting H5, increasing age was associated with participants’ own use of justifications about comfort, β = .348, χ2(1) = 7.775, p = .005, Exp(B) = 1.416.

The effect of participant response was significant, χ2(2) = 78.059, p < .001. Participants were more likely to reference the benefits of diversity when predicting that the club would select the race match peer, and more likely to reference similarity and comfort when predicting that the club would select the wealth match peer, β = 4.945, χ2(1) = 29.614, p < .001, Exp(B) = 140.513. Neither club race (χ2(2) = .974, p = .614) nor participant race (χ2(2) = .779, p = .667) had a significant impact on participants’ justifications.

Discussion

Overall, the majority of children in the current study expected others to include a peer into their after-school club on the basis of wealth rather than on the basis of race, and this pattern was higher for the high wealth club (82%) than the low wealth club (75%). No prior research, to our knowledge, has been conducted on children’s peer inclusion decisions based on wealth and race. In this study, wealth was a more salient factor for children and adolescents than race when making predictions and forming preferences about whom to include into a club, and this was the case for a sample in which both African American and European American participants were evenly represented, and who came from middle-income backgrounds.

A novel finding was that, with age, European American and African American children and adolescents made different predictions about what they expected peer clubs to do when deciding whom to include. With age, European American participants were increasingly likely to predict that clubs would select on the basis of wealth. While overall African American participants were also more likely to predict same-wealth inclusion, with age, they were less likely to do so and more likely to predict that clubs would select on the basis of race. Importantly, when asked about their own preferences, the majority of African American (79%) and European American (73%) participants, regardless of age, stated that they would prefer to include a peer who matched on wealth, not race.

This finding, which was in line with our hypothesis about participants’ predictions for others’ behavior, likely reflects African American early adolescents’ recognition of discrimination and interracial exclusion, which is often a persistent experience in their own lives (Brown, 2017; Rogers, 2019) and which, in turn, may impact their assessments of how others might respond in interracial inclusion contexts (Cooley et al., 2019). For instance, African American children in previous studies may have been particularly attuned to the act of interracial exclusion because of past experiences with exclusion and discrimination based on race (Beaton et al., 2012; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014; Ruck et al., 2014). Further, research on family racial socialization has demonstrated that African American children and adolescents, more so than their European American peers, receive messages about race and potential bias early in life, and are likely more aware of potential discrimination that they may encounter (Hughes et al., 2011; Seaton et al., 2012).

These findings were further supported by children’s and adolescents’ own inclusion preferences. While European American participants’ own preferences matched their predictions for what others would do, African American participants’ own preferences differed from their predictions for others’ decisions. Regardless of age, African American participants preferred clubs to include on the basis of wealth rather than on the basis of race. Previous research has shown that African American adolescents often expect interracial exclusion (regardless of the race of the excluded child), due to their personal experiences with discrimination (Cooley et al., 2019). Indeed, in many countries around the world, ethnic minority children who perceive exclusion as discriminatory are especially likely to reject the act as wrong (Thijs, 2017). It may also be that African American children and adolescents have a more developed perspective about interracial contact and experiences than European American children and adolescents given the early awareness for children of color about issues of social exclusion (e.g., Kinzler & Dautel, 2012). Future research with older age groups needs to be conducted to shed light on how to interpret these findings regarding the development of predictions and preferences about interracial and interwealth peer inclusion.

These findings provide a new lens for conceptualizing how children and adolescents think about race-based inclusion and exclusion. Rather than focusing solely on race, a common approach in research on intergroup attitudes, the current pattern of results indicate that race and wealth are entangled, even in children’s and adolescents’ peer inclusion decisions. For many European American children and adolescents in this study, when wealth was controlled, interracial groups were preferred over interwealth groups. This finding is novel and important as it demonstrates a context in which a majority racial group, European Americans, desire interracial peer groups. Support for interracial peer friendships is significant developmentally given that interracial friendships often decline with age. Given that interracial friendship has been shown to reduce prejudice and bias among majority group children, this finding provides another variable (wealth) that warrants further investigation (Tropp & Prenovost, 2008).

Much research has demonstrated contexts in which European American children associate wealth with race (Shutts et al. 2016), and thus these findings might also imply that racial exclusion reflects biases about wealth in addition to biases about race. That is, European American children who display racial biases may do so, in part, due to their additional assumption that ethnic minority peers are from low-wealth backgrounds and share little similarities in the way of interests. Addressing wealth biases will be important for reducing not only prejudice based on wealth but may also impact biases that drive exclusion based on race.

Interestingly, the majority of children and adolescents expected and predicted same-wealth preferences for peer inclusion whether the group was low wealth (“poor”) or high wealth (“rich”). Based on same-race preferences which are pervasive in the research literature (Brown, 2017), one might expect that participants’ same-race bias would predict that a low wealth European American club would pick a high wealth European American target (matching on race) to join their club rather than a low wealth African American target (matching on wealth, but not race). Thus, these perceived same-wealth preferences existed for both high wealth and low wealth groups, demonstrating the saliency of perceptions of wealth status.

Participants’ reasoning also supported the view that wealth is a salient form of group identity, given that the majority of participants cited perceptions of similarity and comfort for why high and low wealth groups would choose to include someone of the same wealth background. With age, participants increasingly referenced comfort when predicting or preferring ingroup inclusion. This may be because participants recognize wealth as a form of group identity that may impact preferences, interests, hobbies, and afterschool activity choices. Given that previous research has shown that children often justify selective ingroup inclusion on the basis of perceived comfort with the ingroup this finding sheds light on the types of assumptions that children make to determine shared group interests (Hitti & Killen, 2015; Stark & Flache, 2012).

A future avenue for research could be to examine the factors that children and adolescents believe to be the source of wealth status, in order to understand the reasons for these assumptions. We documented that with age participants referred to a “comfort” level with same-wealth peers, however it is not clear what underlies this perception of comfort. Comfort might refer to being with peers with the same access to resources and opportunities. Alternatively, perceived comfort may reflect a set of stereotypic expectations about peers from low or high wealth backgrounds. This remains to be better understood and investigated.

The current study sampled middle-SES African American and European American participants. Matching the samples by family income and education level avoided the confound of race and SES that persists in child development research (Rogers, 2019; Ruck, Mistry, & Flanagan, 2019). In many studies, the development of lower-SES African American children is compared with the development of middle- or higher-SES European American children. This overlooks the experiences and perspectives of middle- and higher-SES African American samples as well as lower-SES European American samples, all of whom represent important proportions of the U.S. population. Moreover, it limits empirical understanding of the respective roles that these two group memberships play in children’s developing social cognition and social experiences of inclusion and exclusion.

An important next step for this line of research should be to assess in what ways children’s own racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, together, inform their views on peer inclusion and exclusion in contexts involving both race and wealth (or SES) together. Because the majority of the participants in the study came from middle to upper-middle income families, investigating the role of participants’ own wealth background was not feasible in the current study. To examine the role of both racial and wealth background in these research questions, it is necessary to conduct a large study in which race is represented evenly at different economic levels (e.g., low-, middle- and high-SES African American and European American participants), as well as the administration of comprehensive measures of wealth that include family income as well as monetary and material assets.

Evidence from children’s evaluations of racial- and gender-based exclusion has shown that children who are members of social groups that are typically viewed as lower on a social-cultural hierarchy often evaluate exclusion more negatively than their higher status peers (Cooley et al., 2019; Grütter et al., 2018; Mulvey, 2016). It is not yet known whether this pattern would extend to wealth group membership, however, as ingroup preference might also motivate both high and low wealth children to prefer inclusion of same-wealth peers.

It would also be very interesting to study how these preferences might change when taking an intersectional framework. It is possible that differences in African American and European American children’s predictions and preferences about inclusion will emerge based on their own economic position, and particularly when considering groups that are not consistent with all of children’s relevant group memberships. For example, it is possible that high wealth children might differentially prefer to include high wealth peers that share their racial group membership compared to high wealth peers that do not share their racial group membership. It is also possible that children may have different perceptions of high- and low-wealth clubs based on their racial group membership, and that in certain contexts, wealth may be considered the more important social group membership while in other contexts race may be viewed as more important. Thus, further investigation with participants representing a wider range of wealth statuses is necessary.

Recent research on wealth inequalities has shown that children are aware of status hierarchies (Arsenio & Willems, 2017; Elenbaas, 2019a) and that this knowledge does not always reflect negative stereotypes about low wealth peers but rather an understanding that society (and parents) will look negatively on interactions between high and low wealth peers (Grütter et al., 2018). How children and adolescents think about wealth status and wealth inequalities could provide more information about what underlies their predictions about peer inclusion based on race and wealth.

Further, studying how children and adolescents conceptualize wealth and wealth inequalities, specifically whether they view the source of wealth as individual and structurally based, may provide more differentiated information regarding what reasons underlie participants’ expectations about same-wealth comfort. Individual factors include hard work, effort, motivation, and other variables that might pertain to individual successes or failures whereas structural factors include societal conditions that enable or constrain mobility, including access to resources related to one’s socioeconomic status as well as race (Heckman & Mosso, 2014). While some adolescents view social hierarchies based on wealth as a reflection of structural inequalities (Flanagan et al., 2014), often children, adolescents, and adults put emphasis on individual factors (Burkholder, Sims et al., 2019). It is an open question whether these explanations for the source of wealth bear on children’s and adolescents’ preferences for same-wealth peers. Perhaps those individuals who recognize structural wealth barriers may have a different set of expectations about interwealth peer relationships than those who view wealth obtainment as based on individual effort and hard work.

Overall, the present study found that children and adolescents both personally preferred, and expected others to prefer, to include peers that matched their wealth group membership rather than peers that matched their racial group membership into after-school clubs. However, these expectations differed by children’s and adolescents’ own racial group membership, with predictions of same-wealth inclusion increasing with age among European American participants and decreasing with age among African American participants. The present study thus revealed that the factors children consider most important for peer inclusion differed by children’s and adolescents’ racial group membership. Encountering peers of different racial and wealth statuses is a common experience in childhood and adolescence (Killen et al., 2013; McGuire et al., 2015; Rutland et al., 2017), thus it is vitally important for developmental research to continue to examine how children’s own social group memberships, and the unique experiences associated with those social group memberships, impact desires for intergroup contact, social inclusion, and friendships. By understanding the factors that children take into consideration when making social inclusion and exclusion decisions in peer contexts, intervention and prevention programs can better reduce prejudice and bias as well as promote intergroup friendships in childhood and adolescence.

Acknowledgements:

Amanda R. Burkholder was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE 1322106 while working on this project. Melanie Killen was supported, in part, by a National Science Foundation grant, BCS 1728918 and by a National Institute for Child Health and Human Development award, R01HD093698.

Contributor Information

Amanda R. Burkholder, University of Maryland

Laura Elenbaas, University of Rochester.

Melanie Killen, University of Maryland.

References

- Aboud FE, Mendelson MJ, & Purdy KT (2003). Cross–race peer relations and friendship quality. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 165–173. 10.1080/01650250244000164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio W, & Willems C (2017). Adolescents’ conceptions of national wealth distribution: Connections with perceived societal fairness and academic plans. Developmental Psychology, 53, 463–474. 10.1037/dev0000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton AM, Monger T, Leblanc D, Bourque J, Levi Y, Joseph DJ, … Chouinard O (2012). Crossing the divide: The common in–group identity model and intergroup affinity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36, 365–376. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS (2017). Discrimination in childhood and adolescence: A developmental intergroup approach. Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder AR, D’Esterre AP, & Killen M (2019). Intergroup relationships, context, and prejudice in childhood. In Fitzgerald H, Johnson D, Qin D, Villarruel F, & Norton J, (Eds.), Handbook of children and prejudice: Integrating research, practice and policy (pp. 115–130 ). Springer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder AR, Sims RN, & Killen M (2020). Inclusion and exclusion. In Hupp S & Jewell J (Eds.) The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development. Wiley Blackwell. 10.1002/9781119171492.wecad401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder AR, Sims RN, & Killen M (2019, March). Children’s and adolescents’ evaluations of different causes of wealth inequality. In Burkholder AR (Chair), Children’s view of social inequality: Evaluations and decisions about wealth. Symposium conducted at the biennial meeting of the Society of Research on Child Development, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley S, Burkholder AR, & Killen M (2019). Social inclusion and exclusion in same-race and interracial peer encounters. Developmental Psychology, 55, 2440–2450. 10.1037/dev0000810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L (2019). Perceived access to resources and young children’s fairness judgments. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 188, 104667. 10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2016a). Research in developmental psychology: Social exclusion among children and adolescents. In Riva P & Eck J (Eds.), Social exclusion: Psychological approaches to understanding and reducing its impact (pp.89–108). NY: Springer Publishing Company. 10.1007/978-3-319-33033-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2016b). Age-related changes in children’s associations of economic resources and race. Frontiers in Psychology, 7:884. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, & Lang A-G (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA, Kim T, Pykett A, Finlay A, Gallay E, & Pancer M (2014). Adolescents’ theories about economic inequality: Why are some people poor while others are rich? Developmental Psychology, 50, 2512–2525. 10.1037/a0037934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grütter J, Dhakal, & Killen M (2018, September). Growing up with cultural and social diversity in strong social hierarchies: Adolescents’ interpretations of discrimination and potential for cross-group friendships in Nepal. Paper presented at the 51st Congress of the German Psychological Society, Frankfurt, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GC, Yip YN, & Zarate MA (2016). On becoming multicultural in a monocultural research world: A conceptual approach to studying ethnocultural diversity. American Psychologist, 71, 40–51. 10.1037/a0039734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, & Mosso S (2014). The economics of human development and social mobility. Annual Review of Economics, 6, 689–733. 10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitti A, & Killen M (2015). Expectations about ethnic peer group inclusivity: The role of shared interests, group norms, and stereotypes. Child Development, 86, 1522–1537. 10.1111/cdev.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, McGill R, Ford K, & Tubbs C (2011). Parents, peers, and schools as agents of racial socialization for African American youth. In Hill N, Mann T & Fitzgerald H (Eds.) African American children’s mental health: Development and context (pp. 95–124). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst CE, Gibbon HMF, & Nurse AM (2017). Social inequalities: Forms, causes, and consequences. NY: Routledge: (Taylor & Francis Group; ). [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, & Graham S (2006). Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science, 17, 393–400. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Henning A, Kelly MC, Crystal D, & Ruck M (2007). Evaluations of interracial peer encounters by majority and minority U.S. children and adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31, 491–500. 10.1177/0165025407081478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Kelly MC, Richardson C, Crystal D, & Ruck M (2010). European-American children’s and adolescents’ evaluations of interracial exclusion. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13, 283–300. 10.1177/1368430209346700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Mulvey KL, & Hitti A (2013). Social exclusion in childhood: A developmental intergroup perspective. Child Develeopment, 84, 772–790. 10.1111/cdev.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, & Rutland A (2011). Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. New York, NY: Wiley/Blackwell Publishers. 10.1002/9781444396317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, & Dautel JB (2012). Children’s essentialist reasoning about language and race. Developmental Science, 15, 131–138. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy RL (1981). The development of the conception of economic inequality. I. Descriptions and comparison of rich and poor people. Child Development, 52, 523–532. 10.2307/1129170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AK, Seaboyer L, & Garcia Coll C (2015). Academic achievement. In Suarez-Orozco C, Abo-Zena M, & Marks AK (Eds.), Transitions: The development of children of immigrants (pp. 259–275). NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire L, Rutland A & Nesdale D (2015), Peer group norms and accountability moderate the effect of school norms on children’s intergroup attitudes. Child Development, 86,1290–1297. 10.1111/cdev.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Brown CS, White ES, Chow KA, & Gillen-O’Neel C (2015). Elementary school children’s reasoning about social class: A mix-methods study. Child Development, 86, 1653–1671. 10.1111/cdev.12407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller SJ, & Tenenbaum HR (2011). Danish majority children’s reasoning about exclusion based on gender and ethnicity. Child Development, 82, 520–532. 10.1111/j.1467-8264.2010.01568x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL (2016). Children’s reasoning about social exclusion: Balancing many factors. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 22–27. 10.1111/cdep.12157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D (2004). Social identity processes and children’s ethnic prejudice. In Bennett M & Sani F (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 219–245). East Sussex, England: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D, & Lawson MJ (2011). Social groups and children’s intergroup attitudes: Can school norms moderate the effects of social group norms? Child Development, 82, 1994–1606. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Shutts K, Kinzler KD, & Weisman KG (2012). Children associate racial groups with wealth: Evidence from South Africa. Child Development, 83, 1884–1899. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Williams A, & Steele JR (2016). Children’s racial categorization in context. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 33–38. 10.1111/cdep.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton E, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, ….Yip T (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychological, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85, 40–57. 10.1111/cdev.12200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO (2019). Commentary on economic inequality: “What” and “Who” constitutes research on social inequality in developmental science? Developmental Psychology, 55, 586–591, 10.1037/dev0000640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SO, Williams AD, & Gelman SA (2017). Children’s and adults’ predictions of Black, White, and multiracial friendship patterns. Journal of Cognition and Development, 18, 189–208. 10.1080/15248372.2016.126237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LO, Scott MA, & Way N (2015). Racial and gender identity among black adolescent males: An intersectionality perspective. Child Development, 86, 407–424. 10.1111/cdev.12303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD, Mistry RS, & Flanagan CA (2019). Children’s and adolescents’ understanding and experiences of economic inequality: An introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 55, 449–456. 10.1037/dev0000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD, Park H, Crystal DS, & Killen M (2014). Intergroup contact is related to evaluations of interracial peer exclusion in suburban and urban African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1226–1240. 10.1007/s10964-014-0227-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, Killen M, & Abrams D (2010). A new social-cognitive developmental perspective of prejudice: The interplay between morality and group identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 279–291. 10.1177/1745691610369468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, Nesdale D, & Brown CS (2017). Handbook of group processes in children and adolescents. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Santos CE, & Toomey RB (2018). Integrating an intersectionality lens in theory and research in developmental science. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2018(161), 7–15. 10.1002/cad.20245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, Morgan-Lopez A, & Sellers RM (2012). Racial discrimination and racial socialization as predictors of African American adolescents’ racial identity development using latent transition analysis. Developmental Psychology, 48, 448–458. 10.1037/a0025328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seider S, Clark S, & Graves D (2019). The development of critical consciousness and its relation to academic achievement in adolescents of color. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K, Brey EL, Dornbusch LA, Slywotzky N, & Olson KR (2016). Children use wealth cues to evaluate others. PLoS ONE, 11, e0149360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK (2012). Rich man, poor man: Developmental differences in attributions and perceptions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113, 415–429. 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK (2013). Age differences in perceptions of rich and poor people: Is it skill or luck? Social Development, 22, 1–18. 10.1111/sode.12000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development: How teens construct their world. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J, Jambon M, & Ball C (2014). The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. In Killen M & Smetana J (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 23–45). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark TH, & Flache A (2012). The double edge of common interest: Ethnic segregation as an unintended byproduct of opinion homophily. Sociology of Education, 85, 179–199. 10.1177/0038040711427314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel S & Austin W (Eds.) Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Thijs J (2017). Children’s evaluations of interethnic exclusion: The effects of ethnic boundaries, respondent ethinicity, and majority in-group bias. Journal of Experimetnal Child Psychology, 158, 46–63. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, & Prenovost MA (2008). The role of intergroup contact in predicting children’s inter–ethnic attitudes: Evidence from meta–analytic and field studies. In Levy SR & Killen M (Eds.), Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood (pp. 236–248). Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2002). The culture of morality: Social development, context, and conflict. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woods TA, Kurtz-Costes B, & Rowley SJ (2005). The development of stereotypes about the rich and poor: Age, race, and family income differences in beliefs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 437–445. 10.1007/s10964-005-7261-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]