Abstract

Objective

Our paper aims to present Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) guidelines for health technology assessment (HTA) in India.

Methodology

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted to retrieve information on existing BIA guidelines internationally. The initial set of principles for India were put together based on an interactive process between authors, taking into consideration the existing evidence on BIA and features of Indian healthcare system. These were reviewed by Technical Appraisal Committee (TAC) of Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn) for their inputs. Three rounds of consultations were held before finalising the guidelines. Finally, user feedback on the draft guidelines was obtained from the policy makers and programme managers involved in the budgeting decisions.

Results

We recommend a payer’s perspective, which will include both a multi-payer (depicting the current situation in India) and a single-payer scenario (which reflects a futuristic universal health care situation). A time horizon of 1–4 years is recommended. For estimation of eligible population, a top-down approach is considered appropriate. The future and current mix of interventions should be analysed for different utilisation and coverage patterns. We do not recommend discounting; however, inflation adjustments should be performed. The presentation of results should include total and disaggregated results, segregated year-wise throughout the chosen time horizon, as well as segregated by the type of resources. Deterministic sensitivity analysis and scenario analysis are recommended to address uncertainty.

Conclusion

Our recommendations, which are tailored for the Indian healthcare and financing context, aim to promote consistency and transparency in the conduct as well as reporting of the BIA. BIA should be used along with evidence from economic evaluation for decision making, and not as a substitute to evidence on value for money.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Our recommendations for the conduct of Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) aim to promote consistency and transparency in the conduct as well as reporting of the analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first set of BIA recommendations for India, which addresses the intricacies of the healthcare system and financing in India. |

| Our recommendations are a set of robust guidelines, which can be used to assess drugs, health technologies as well as health programmes in contrast to the existing guidance being available to assess financial impact of mainly drugs and devices. |

| Both BIA and cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) are independent tools, which aid the process of evidence-informed decision making and complement the findings of each other. Thus, these are not to be considered a substitute for each other. |

Background

Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) is a relatively recent method to assess the affordability of healthcare technologies. In recent decades, BIA has gained popularity as a tool to support budget holders in making policy decisions by considering the affordability of new healthcare technologies [1, 2]. BIA evidence has also been used in making decisions around priority setting, together with evidence from cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), which alone might not provide sufficient evidence to guide resource allocation [3, 4]. For instance, treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with Directly Acting Antivirals (DAAs) was reported to be cost saving in India [3]. However, owing to its huge budget impact, the costly DAAs were introduced for treatment among only a subset of HCV patients, i.e., those with cirrhosis. In another extreme example, BIA evidence shaped policy guidelines for the inclusion of imiglucerase (required for the treatment of Gaucher’s disease, Type 1) in National List of Essential Medicine (NLEM) in Thailand. Even when it was not deemed cost effective, this drug was included in the benefit package owing to its minimal budget impact as it was required by only a very small percentage of population. Moreover, non-inclusion of imiglucerase in the NLEM would have had inequitable impact on access for bone marrow transplant (which is covered under the Universal Health Coverage [UHC] benefit package) as imiglucerase is required before undergoing transplant [4]. These examples illustrate that both BIA evidence as well as cost effectiveness should together guide decision makers.

BIA can be a highly informative assessment as we move towards achieving UHC, especially in resource constrained settings. As per the stated policy goals, India is committed towards achieving UHC [5]. However, the allocation to health is not commensurate with the aspirational goals [5, 6]. With such restrained budget, affordability and financial sustainability assessments become equally important alongside value for money when making decisions on resource allocation between competing healthcare technologies. Second, the National Health Policy 2017 envisions an increase in the government health expenditure to 2.4% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2024 [6–8]. Third, the Indian government’s flagship health scheme, Ayushman Bharat, was announced recently, which includes two components: creation of health and wellness centres (HWCs) for strengthening primary health care and the ‘Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana’, which is an insurance programme to cover hospitalisation expenditures [9]. Together, this implies an increased pressure on expanding the basket of services and interventions to be provided, and increase their population coverage, which further places utmost importance on the need to prioritise the available resources in a sustainable way [10].

The Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn)—India’s official HTA agency [11, 12], has produced a process manual, which also specifies a reference case to conduct CEA [13]. However, there are no BIA guidelines specific to the Indian context. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) has published the principles of good practice to follow when developing and reporting a BIA [14, 15]. In addition, a number of countries have developed their own country-specific guidelines to address aspects that are specific to their healthcare system [16–19]. However, the generalisability of these guidelines to the Indian context is limited owing to contextual differences in the health financing system in India.

The healthcare system in India differs in many aspects from other countries where BIA guidelines are available [20–23]. The private sector in India predominates over public in provision of healthcare and a significant proportion of healthcare is financed through household out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) [24, 25]. Furthermore, health financing structure includes a complex mix of demand as well as supply-side financing mechanisms [26, 27]. The supply-side financing system refers to the funding flows that are created to invest on development of health infrastructure, pay for a supply of human resources, drugs and consumables, etc. [28]. These are usually guided by norms of payment for each level of health facility. There is no explicit linkage between the level of funding received and volume of services delivered in a supply-side financing route. On the contrary, in a demand-side financing system, money follows the patient/consumer. The provider gets paid according to the volume of services delivered or number of patients treated [28]. The payment system under all publicly financed insurance systems in India is an example of demand-side financing. Historically, the financing of public healthcare in India was largely supply-side driven. However, with the recent rise in number of publicly financed health insurance schemes, there is a transition to demand-side approach for financing healthcare [29]. The launch of Ayushman Bharat—Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) is a major step forward in this direction [9]. The demand-side financing operates through two types of mechanisms, i.e., a ‘public trust model’ where the government purchases the service from other public or private providers or an ‘insurance-based model’, wherein the government acts as the central funding agency but the purchasing of healthcare is by the insurance intermediary [30]. Overall, demand-side financing aims at improving access to healthcare and encourage supply of healthcare, for example, public health insurance schemes [30]. These are important contextual differences that should be considered when computing a framework to assess financial consequences of the introduction of new healthcare technologies or interventions.

Consequently, in order to meet the current requirement of using BIA alongside CEA to incorporate evidence on financial sustainability and affordability in HTA decision making, it is important to develop and use a set of methodological recommendations, which takes into consideration the specific features of Indian healthcare financing and delivery system. These recommendations can be used by healthcare decision makers at both micro (for example, hospitals, district) and macro (regional, state and centre) level, as well as HTA researchers who wish to conduct BIA to inform decision making in health. Decision makers could be policy makers with responsibility of deploying funds. The interventions could range from services that are a part of the benefit package under the AB PM-JAY to supply-side funded interventions provided through State or Central Government funding or National Health Mission (NHM). Any intervention aimed at improving the health of a given population including pharmaceuticals; medical devices; diagnostic/screening techniques; surgical procedures; other therapeutic technologies; preventive or other public health programmes can be assessed for budget impact.

In this paper, we aim to present the BIA guidelines for its conduct specific to Indian context, allowing for the flexibility to estimate the financial impact for different budget-holders and at different organisational levels within the Indian healthcare system.

Guidelines Development Process

The work for developing BIA guidelines was commissioned by HTAIn, Department of Health Research (DHR). The development of the present BIA guidelines involved a multi-step approach to ensure recommendations are based on all available evidence on BIA and are appropriate considering the complexity of the Indian healthcare system. A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted to retrieve information on all currently available BIA guidelines internationally [31]. The initial set of BIA principles for India were put together via an interactive process between authors and taking into consideration both existing BIA evidence [31] and the features of the healthcare system in India. The authors deliberated on why the existing BIA guidelines cannot be adapted to the Indian scenario, and which features of existing guidelines can be generalised. The healthcare service delivery and financing were discussed in detail to formulate BIA costing and modelling approach. In addition, the guiding principles were formulated to set an appropriate time horizon for BIA. Similarly, the recommendation on each guiding principle were discussed in light of opinion of each author and a consensus was generated amongst all by discussion.

After preparation of the initial draft, the guidelines were circulated three times via e-mails to the members of Technical Appraisal Committee (TAC) of HTAIn for their inputs and suggestions. After obtaining comments and feedback by e-mail, the revised guidelines were presented twice in virtual meetings to discuss the recommendations. Eight members of the TAC, and 13 members of the HTAIn secretariat participated in these meetings. In addition, seven members from the regional resource centres (RRC) were also a part of these virtual meetings. RRCs are the academic and research organisations where HTA studies are commissioned by HTAIn to conduct evaluation. The members of RRCs who participated in the meetings were researchers who are involved in conducting HTA assessments, including BIA. In view of the current coronavirus disease (COVID)-19 pandemic, it was not possible to have face-to-face meetings, and hence, virtual meetings were held.

Based on the inputs and suggestions received via e-mail communication and during these two virtual meetings, two sets of revisions were made. After the guidelines were approved by the TAC, these were shared with a panel of users of BIA evidence who are involved in undertaking budgetary decision-making for allocation of resources across different programmes and policies in varying capacities. The users to be interviewed were purposively selected. This panel included nine bureaucrats, policy makers and technical experts responsible for budgetary decision-making in the Indian health system. We first circulated the BIA draft guidelines to these experts via e-mail. Two of these did not respond even after two reminder e-mails. Among those who responded and provided feedback, three users had experience of working at the national level, while four users worked at the State level. In terms of financing models in which the users worked, five were involved in a supply-side financing system and two users in the demand-side financing schemes. Similarly, while three users were involved in global budgeting decisions, the remaining four users were responsible for making decisions about single health programmes or schemes or interventions.

The users or policy makers or budget holders on the panel responded to the guideline document with their queries, seeking clarifications, providing their suggestions and overall feedback on the document. To resolve the queries and to assess the understanding of the experts regarding the document, one-to-one telephonic interviews were conducted for each of these seven experts. None of the expert comments led to any disagreement in broad principles as most of the comments were generic, seeking further clarification on different aspects in the document. Majority of the suggestions, which were to provide greater details, were incorporated. A few comments, which were beyond the scope of BIA, were explained to the experts to gain consensus. This complete process, that included e-mail communications, virtual meetings and expert interviews, was completed over a period of five months from June to October 2020.

Recommendations For conduct of BIA in India

Perspective

“BIA from the budget holder’s or payer’s perspective should be done from two scenarios. First, using a ‘multi-payer’ perspective to assess the current existing share of budget holder and out of pocket (OOP) expenditure, which is the existing situation in India where healthcare expenditure is borne by the government as well as the patients. Second, using a ‘single payer’ perspective where universal access to services would be guaranteed by the budget holder without any OOP expenditure.”

BIA is a computational framework to be used alongside CEA to provide information on the resources required to fund a new intervention. Together with information on the level of future economic growth at national level, ability of the Government to raise revenue, as well as the ability of the public sector to raise resources for health within the overall revenue, evidence from BIA helps to provide insight on the fiscal sustainability of scaling-up newer interventions. Thus, we recommend that the BIA should be conducted from the perspective of a healthcare payer. However, owing to the organisation of healthcare funding in India, there might be multiple players who can be designated as the budget holders or healthcare payers. Nearly, 62 % of the total health expenditure is borne out of pocket (OOP) by households [32]. In cases where OOP expenditures are used to pay for healthcare services in the routine scenario, the resources for which OOP expenditure is being incurred should also be valued. Thus, we recommend that a BIA from the budget holder’s or payer’s perspective should be done from two scenarios. First, using a ‘multi-payer’ perspective to assess the current existing share of budget holder and OOP expenditure, which is the existing situation in India where healthcare expenditure is borne by the government as well as the patients. In any case, the estimation of OOP expenditure will include any form of cost-sharing such as in case of user fee, co-payment, co-insurance or deductibles as well as OOP expenditure on medicine, diagnostics, travel, etc.

Second, the BIA would be conducted using a ‘single payer’ perspective where universal access to services would be guaranteed by the budget holder without any OOP expenditure. In this futuristic scenario, the resources for which OOP expenditure is incurred should be measured in terms of quantity, while its valuation would be done using pricing of a scenario where these resources will not be valued as per the market rates, but in a scenario where these resources (which are currently financed out of pocket) are procured centrally by the single large payer. This approach and methodology has also been used recently for determining the provider-payment rates for the benefit package of AB PM-JAY [33, 34]. This approach is to account for the assumption that large public procurement will lead to reduction in the prices. This has been demonstrated by different states like Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan in India, where medical service corporations have taken the role of centralised drugs and medical device procurement [35–37]. However, this may be an underestimation of the current impact of OOP expenditure. Disaggregated budget impact in terms of health system and OOP expenditure under both the scenarios will be presented in order to inform the relevant stakeholders. The system, perspective and the costing in these two scenarios has been summarised in Table 1 [24, 38–40].

Table 1.

Description of perspectives for budget impact analysis (BIA) in India

| Routine scenario (multi-payer perspective) | UHC scenario (single-payer perspective) | |

|---|---|---|

| Description | Valuation at current existing share of budget holder and OOP expenditure | Universal access to services would be guaranteed by the budget holder without any OOP expenditure |

| Perspective | Multi-payer | Single payer |

| Type of payers | Public payer, patients, and any other payer | Public payer |

| Type of costs | Stratified estimates for health system costs and private costs including OOP expenditure | Full cost for delivering healthcare by single payer, without any OOP expenditure |

| Valuation of health system costs | Valuation of resources is at current capacity utilisation | Cost will be adjusted for changes in utilisation in the UHC scenario |

| Valuation of OOP expenditure | OOP expenditure will be based on existing situation and prevailing market prices Obtained from NSSO/ or other primary patient survey | Resources which incurred OOP expenditure will be valued at prices of centralised public procurement from a single payer’s perspective |

NSSO National Sample Survey Organization, OOP Out of pocket, UHC Universal Health Coverage

Time Horizon

“We recommend allowing the flexibility to present results from a minimum of 1 year to a maximum of 4 years, beyond which we expect the level of uncertainty on the estimate would be too high. The choice of the selected time horizon should be clearly stated and justified.”

The time frame chosen for the BIA should conform to the requirement and budgeting process of the budget holder as well as the time it takes for a new technology to reach its optimum or desired coverage. However, there may be certain guiding principles which are to be considered while identifying a suitable time horizon. First, it can depend on the budgeting process in the context of interest, for example, hospital, state, region. It could be related to the duration of planning cycle of a government programme, if applicable or any set of monitorable targets that are to be achieved in a particular time. Second, the choice of time horizon should also consider the general cycle of policy change with regard to increments in benefit package. A third important factor affecting this choice could be the life of capital investments such as buildings and other required infrastructure, equipment, trainings, etc. Further, the likely pace of adaptation of a new healthcare technology or intervention in the Indian setting will be an important consideration for selecting an appropriate time frame for assessing the budget impact. Last, we also need to consider the likely scale-up of coverage for any new health intervention introduced. The coverage in initial years is expected to be low and might gradually increase in the following years. Thus, the time horizon should also factor in the impact of coverage.

While the time-horizon should be long enough to ensure all considerations cited above are captured, it should be noted that the longer the time horizon, the greater the assumptions which need to be made about the future. This would increase the level of uncertainty in the results.

For the reasons mentioned above, and because the relevant time horizon may differ based on the chosen intervention and the perspective of the budget holder, we recommend allowing the flexibility to present results from a minimum of 1 year to a maximum of 4 years, beyond which we expect the level of uncertainty on the estimates would be too high. The choice of the selected time horizon should be clearly stated and justified on any of the above grounds or any other relevant criteria.

Eligible Population

“Estimation of the eligible population should reflect the demographic and epidemiologic characteristics of a health condition, indication for the intervention, recommendations by the clinical treatment guidelines, access as well as care-seeking patterns for the intervention. We recommend a top-down approach for the estimation of eligible population.”

BIA population is defined as an open cohort, which means that patients may enter and leave throughout the time horizon of the analysis. New patients or service clients enter the analysis in every year because they develop the condition or meet the criteria for eligibility to the new intervention. The reasons for leaving could be, among others, being cured, falling within criteria for access restrictions and death. Second, this estimation should also take into consideration the standard treatment guidelines for the condition of interest. Third, factors affecting the access to healthcare intervention, which may or may not be related directly to the technology, should also be included in the estimation of the eligible population, for example, its availability, affordability and convenience to use. The estimation of the eligible population should take into account all such changes. Only the defined budget-holder’s population should be considered in the analysis, for example, if the budget-holder is a state government, only the state's population that is eligible for the new intervention should be included.

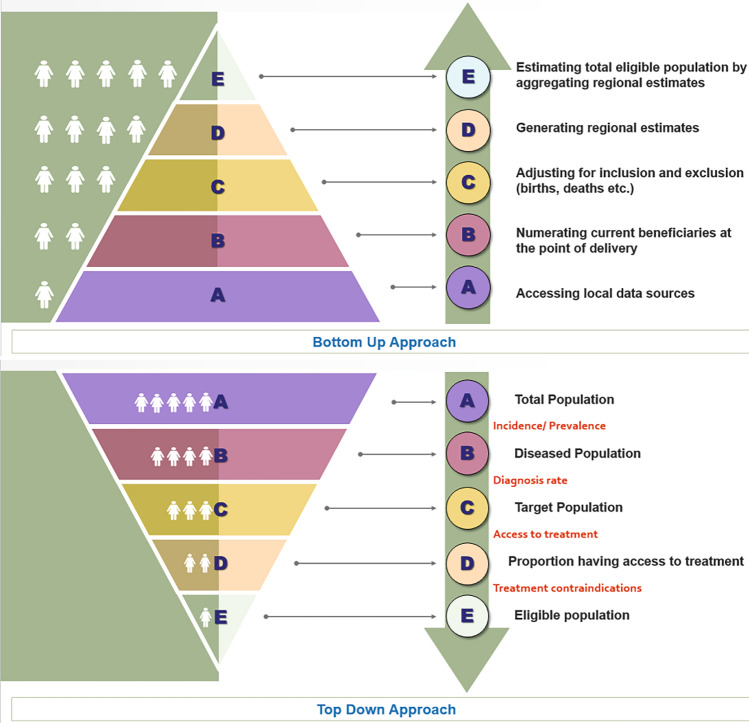

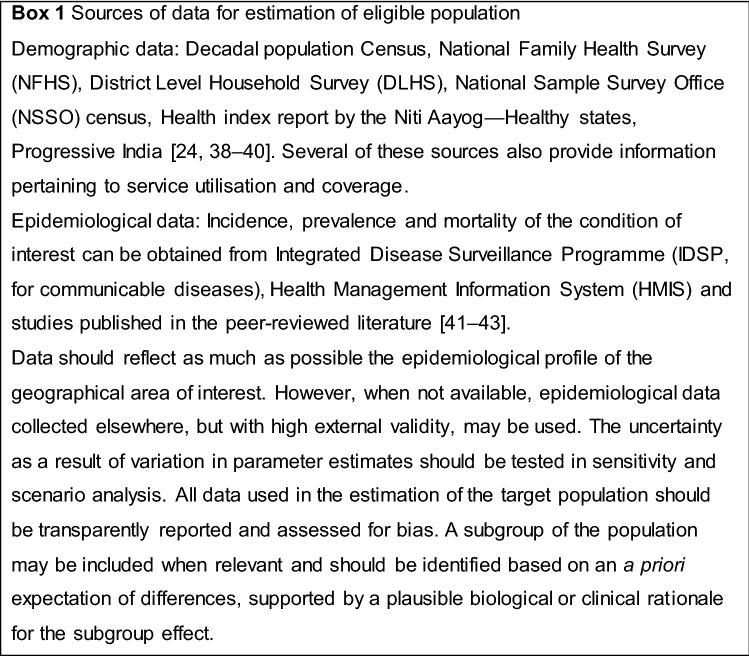

Two main approaches are used to estimate the size of the eligible population: bottom-up and top-down (Fig. 1). The former uses data on the number of patients likely to avail themselves of the new intervention directly provided by the budget-holder. For example, using claims data reporting the number of patients currently treated for the condition of interest. Although this approach may provide more accurate estimates of the target population, such data may not always be easy to retrieve and may not always be transparent, thus making it difficult to assess how accurate they are. By contrast, in top-down approach, one can start from the total population size and apply the epidemiological data which includes the incidence and prevalence estimates and information on restrictions/eligibility to estimate the number of patients eligible for treatment at every year of the analysis. Since this approach breaks down the estimation of the target population in subsequent steps, it is very transparent and allows for inclusion of projections in the demographic and epidemiological changes over time. The top-down approach is therefore considered preferable and should be used when conducting BIA in India.

Fig. 1.

Approaches to estimate eligible population

Various sources of data that can be used for the estimation of eligible population have been summarised in Box 1.

Scenarios to be Compared

“The current mix should represent the existing routine care (without the intervention) in practice for the eligible population whereas the future mix should represent the introduction of the new intervention in addition to routine care for the target population.”

The primary comparator should be the current mix of interventions for the eligible population. The current treatment mix should represent an accurate description of the current situation in terms of currently available healthcare technologies and their respective coverage in real-world practice. It may include a number of different healthcare technologies, no intervention or alternative treatment strategies corresponding to the condition/disease of interest.

The future mix of interventions should represent the routine care for the target population following the introduction of the new intervention. It should therefore include the new intervention in addition to any of the current mix interventions, which are predicted to remain alternative treatment options in the future. The new intervention may be including a part of the existing coverage of one or more of the current interventions or may be added as an add-on to the current mix of interventions.

A BIA will thus compare the total cost of a mix of interventions including the adoption of the new intervention with the total cost of the current intervention mix.

Utilisation Mix and Uptake of the New Intervention

“The estimates of utilisation of an intervention in the current mix should be based on actual available data, which give the current utilisation of routine care in the eligible population. Only if such data are unavailable, evidence-based estimations should be done. For the future treatment mix, the expected estimates of uptake of the new intervention and its utilisation should be based on evidenced-based predictions.”

Utilisation estimates should be used to distribute the eligible population among the healthcare technologies included in the current and future treatment mix. The utilisation estimates at the first year of the analysis may be obtained from local research data or official databases. These estimates of utilisation of an intervention in the current treatment mix may or may not be assumed constant over the time horizon of the analysis. Instead, these should be based on actual available data which give the current utilisation of routine care in the eligible population without the new intervention. Only if such data are unavailable, evidence-based estimations should be done. All predictions should be validated with clinical experts and tested in the scenario analysis. For the future treatment mix, the expected estimates of uptake of the new intervention and its utilisation should be based on evidenced-based predictions. In addition, scale up in use of the intervention with time should also be factored in to assess a realistic budget impact as these patterns tend to change over time (low initial utilisation to gradually increasing utilisation over time).

The existing guidelines for BIA across the globe refer to market shares when describing the distribution among current and future treatment mix [31]. In our recommendations, we refer to utilisation estimates instead of market shares as it better describes the scenario in India. Contextually, the term market share seems more appropriate for interventions like drugs. However, when talking about healthcare programmes or schemes, utilisation and coverage estimates seem to be more appropriate. It is also to be recognised that the estimation of utilisation of a particular service might affect the overall dynamics of the health system. For example, when a screening test is introduced under a public health programme, not only does it incur cost in terms of screening services, but it also influences the utilisation of treatment for the disease being screened and may also change the pattern of utilisation between the public and private sector.

The prediction on the diffusion of the new intervention represents a source of structural uncertainty. The approach to forecasting should therefore be transparently reported and alternative assumptions should be tested in the scenario analysis. Thus, multiple scenarios can be run pertaining to different utilisation estimates. This will also inform the policy makers over the financial resources required for phasing-up a programme/provision of an intervention beginning from low initial coverage followed by gradual increase.

Discounting and Inflation

“We don’t recommend discounting as BIA presents the actual financial implications required to deliver the new intervention over each year of the analysis. Inflation is recommended to update costs/prices of resources used in the model at the current price level.”

BIA aims to present the actual financial implications required to deliver the new intervention over each year of the analysis. For this reason, discounting is not recommended in BIA, meaning that costs should be presented as the existing costs at each subsequent year of the analysis rather than in terms of net present value of future costs, as it is done in CEA [22, 44]. Since information on inflation in the future should be based on predictions, these come with uncertainty. The prices of resources used in each year of the analysis should be presented using the current price level. Inflation will therefore apply only to update costs/prices of resources used in the model at the current price level. This recommendation on inflation is in concurrence with the standard guidelines for budget preparation under NHM—the flagship health programme in India, which states that a 10% increase in budget should be made every year so as to adjust for inflation and increase in demand for services [45]. Moreover, there are several other countries that recommend that inflation adjustments should be made while assessing the budget impact [31].

Approach to Budget Impact Modelling

“Simple cost calculation or decision analytic modelling approach may be used depending on the type of costs to be included for the intervention of interest, complexity of patient evolution patterns and requirements of the budget holder.”

In presenting the financial impact of the new intervention, two main approaches may be used, i.e., simple cost calculation or decision analytic modelling. Spreadsheet-based simple cost-calculation is considered the most appropriate when assessing strictly the direct costs of the new intervention and other health-technologies of interest [15, 46]. In this case, the prices of each healthcare technology considered is multiplied by usage within the time period considered, such as drug administrations for a drug or number of procedures for a diagnostic procedure. The resulting direct cost per healthcare technology considered is then multiplied by the respective coverage and utilisation mix in the current and future scenario to define the total cost of each scenario compared. However, sophisticated mathematical modelling may also be used when assessing only direct costs related the intervention so as to predict and account for complex patient evolution patterns and technology utilisation scenarios.

Alternatively, in cases where wider resource and budgetary implications related to the intervention cannot be credibly captured by using simple cost-calculation approach, decision analytic modelling approaches (a condition-specific cohort or individual simulation model) should be chosen [46, 47]. Examples where such modelling techniques are required may include scenarios where one has to account for cost of clinical outcomes such as costs associated with management of side effects or additional costs incurred due to prolonged survival as a result of the intervention. This approach is quite similar to that used in a CEA; however, in contrast to a CEA, the results of the BIA will only consider the costs associated with resource use rather than the health benefits of the intervention. Thus, a BIA will capture only the monetary impact of an intervention, which may include cost savings due to reduction in complications or side effects as a result of the introduction of the new intervention.

The estimated total cost, which includes the direct healthcare and non-healthcare costs, i.e., related directly to the condition of interest and the healthcare technology under consideration, are then weighted by the respective coverage to arrive at the total cost in the current and future scenarios. Thus, we recommend that a simple cost-calculation or decision analytic modelling approach may be used depending on the type of costs to be included for the intervention of interest, complexity of patient evolution patterns and requirements of the budget holder.

Costing Approach

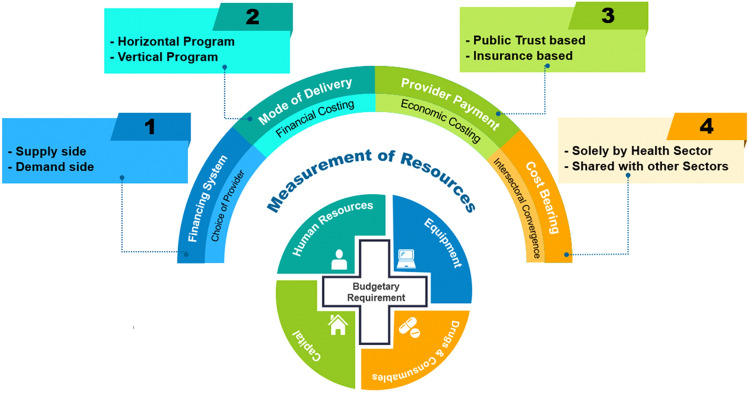

“The assessment of costs should factor in the following considerations: mode of health financing, i.e., whether supply-side or demand-side or mixed; mode of delivering an intervention, i.e., whether vertical delivery or horizontal integration of services; operating provider-payment mechanisms and; identification of who bears the cost of delivering the intervention, i.e., whether health sector or if there is utilisation of resources of departments outside of health as well.”

The costing approach should consider four layers of contextual description for how the healthcare intervention being evaluated will be financed and delivered. First, in order to assess the budget impact of introducing any intervention, it is of utmost importance to understand the operating health financing system. In India, a mix of supply as well as demand mechanisms are used to finance health services [23, 47]. Although the system was historically largely supply driven, the demand side initiatives were introduced recently to improve access and utilisation of health services [30]. Some interventions continue to be delivered through a mix of supply and demand financing. The type of financing system will determine the perspective of costing. In case of a supply financing system, financial cost of “incremental resources” would have to be assessed. On the other hand, for a demand financed intervention, economic cost of “incremental services” would further be estimated based on the provider-payment system, i.e., capitation, fee for service, case-based, etc.

Second, the way in which the current service is being delivered and how the new intervention is likely to be delivered need to be contextually assessed. A supply-side financed intervention could be either delivered by vertical programme or horizontal delivery platforms. Vertical programmes (also known as vertical approach) refer to instances where the solution of a given health problem is addressed through the application of specific measures, for example, National AIDS Control Programme, which involves creation of separate infrastructure and resources, financing flows and monitoring systems [48]. On the contrary, the horizontal or the integrated approach is aimed at tackling the health problems by providing health services which are functionally integrated or co-ordinated with general route of healthcare delivery. NHM is an example of horizontal integration in India, which adopts a synergic approach by providing quality services related to health as well its determinants like nutrition, sanitation, hygiene and safe drinking water [49].

If an intervention is being delivered through a vertical approach, we need to assess whether or not additional resources will be required. If yes, the additional requirement of capital as well as recurrent resources should be quantified and thus valued in monetary terms. Similarly, for health services to be delivered via horizontally integrated health system, we need to assess whether or not the resources required for delivering the health intervention will be met through existing platform. If not, the additional requirements in terms of resources should be estimated both in numbers and monetary terms.

Third, the BIA needs to consider the provider-payment mechanisms for the existing and new intervention. The demand-side financing operates through two types of mechanisms, i.e., a ‘public trust model’ where the government purchases the service from other public or private providers or an ‘insurance-based model’, wherein the government acts as the central funding agency but the purchasing of healthcare is by private bodies [30]. The payment mechanism under such a financing system could be fee for a specific or a set of services provided, capitation based, case-based or per bed day cost of hospitalisation. To estimate the monetary resources required for implementing an intervention using either of these payment mechanisms, it is important to assess the impact of intervention in terms of uptake rate of the intervention, coverage of the current and new health intervention, change in volume of services required, change in drugs/pharmaceutical consumption, change in admission rates of the disease, impact on average length of the stay, associated administrative costs or any other additional input resources required.

Fourth, it is also important to identify who bears the cost of delivering the intervention because several services involve utilisation of resources of departments outside of health. For instance, when services are delivered through horizontal approach, resources of programmes or routine health services, which may not be a part of the line-item budget of the given intervention, are likely to be utilised or may require augmentation. Moreover, it is important to assess whether the resources of other departments outside health are also utilised. For example, Women and Child Development department in India supplements the activities of providing maternal and child healthcare. Another example being the prevention and control services of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) where the government proposes to implement a multi-sectoral action plan which clearly implies that augmentation of resources would also be required for other departments. In terms of reporting the utilisation of resources by departments other than health, the budgetary estimates should be presented separately and not merged with the health sector.

Figure 2 describes the estimation of resources based on mechanism of financing the health intervention.

Fig. 2.

Costing approach across the layers of description for estimating budgetary requirements

In addition to above, to assess the wider financial implications of an intervention, inclusion of patient-associated costs in terms of direct medical (drugs, diagnostics, procedural, hospital charges) along with direct non-medical costs (transportation, boarding and lodging) are also to be considered. In the Indian settings, there are a few examples where direct non-healthcare costs have been included under the benefit package. For instance, the benefit package under AB PM-JAY includes the cost of food and accommodation during the hospital stay but not for transportation. However, to account for transportation-related costs, the government has implemented patient transport/referral services on a large scale. In addition, there are a few other schemes/programmes operating in India where such costs are covered. For example, under the Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK), the pregnant women are entitled to food, accommodation as well as transportation services in addition to all direct healthcare-related services. Similar to this, nutrition support allowance is given to the patients under Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). Thus, in view of this, we would like to recommend that both direct healthcare and direct non-healthcare costs will be included. To account for these costs, one will have to value these resources at prices that the healthcare payer would pay if it were to pay for these resources. However, the inclusion of impact on productivity and other indirect costs in a BIA does not seem relevant to the budget holder. Thus, these costs should not be included in a BIA.

Presentation of Results

“We recommend presenting the total as well as year-wise estimates of budget impact. The estimates should be disaggregated by the type of budget holder, resource use, and should be quantified both in natural as well as monetary units.”

The presentation of the results should be comprehensive, but at the same time, disaggregated effectively to assess the budget requirement at each time point in the chosen time frame. Therefore, we recommend that the total as well as year-wise budget impact be spread across the chosen time horizon. The disaggregated results should be presented by the type of budget holder and organisational level, and type of resource use. In addition, both monetary as well as natural units for the resources used should be given. Natural units refer to physical quantification of additional resources. For example, the number of additional human resource or equipment, etc.

Uncertainty Analysis

“We recommend conducting a deterministic sensitivity analysis to address variation in specific input parameters, and a scenario analysis to test the impact of alternatives for most uncertain/sensitive assumptions.”

Both parameter uncertainty as well as structural uncertainty are introduced while we simulate, as different scenarios of current and future intervention mix are likely to influence the resulting estimates. Due to lack of realistic estimates for many parameters, it is difficult to accurately address much of the parameter uncertainty. However, arbitrary ranges can be assigned for different parameters based on expert opinion. Even then, standard approaches like probabilistic sensitivity analyses used to assess joint parameter uncertainty might not be carried out fully. Thus, we recommend conducting a deterministic sensitivity analysis to address the variation in specific input parameters, and a scenario analysis to test the impact of alternatives for most uncertain/sensitive assumptions.

Discussion

The present document is the first attempt to construct a framework for the conduct of BIA in context of India. Although different countries provide a detailed set of guidelines for BIA, adapting these principles to Indian settings is challenging. There are multiple factors which can be attributed to the complex organisation of health sector in India given the healthcare delivery mechanisms, public-private mix, multiple funding sources as well as the governance structure [21–23]. Thus, a context-specific set of BIA guiding principles is essential that can address these intricacies.

Although most of the recommendations are similar to the existing guidelines, this document reflects the contextual differences in view of the Indian healthcare system. The majority of existing guidelines recommend that the analysis should be performed from the perspective of the payer. While we have also recommended a payer’s perspective, we have also added inclusion of the valuation of OOP expenditures. In addition, we recommend the assessment of BIA both from a multi-payer perspective (current situation in India) as well as a single-payer perspective (UHC scenario). The inclusion of OOP is relevant in Indian context as it accounts for 62 % of the total expenditure on health [32]. The choice of time horizon is also in concurrence with other guidelines [31]. Like others, our recommendation also factors in the budgeting process and the general cycle of policy change in the country to assess the required time horizon. In addition, we also recommend that the utilisation patterns for different interventions or services be incorporated while assessing the resource requirement. The recommendations on other methodological principles such as compared scenarios, estimation of eligible population and approach to modelling are more-or-less in line with the existing guidance [31]. The choice pertaining to these aspects is dependent on the extent of availability and quality of data.

In contrast to the existing guidance, we recommend accounting for the utilisation patterns instead of calculation of market shares. In settings like India, the mere availability of services does not guarantee their utilisation. It might depend on other factors like affordability, accessibility and acceptability of an intervention. Second, our recommendation on the approach to costing differs from other settings [31]. The valuation of resources takes into consideration the structure of health financing in India. It accounts for multiple operating players in the health sector and different modes of health service delivery. This differs from other countries, where the financing of health is largely insurance based [31]. The recommendation on the presentation of results is more or less similar to that recommended by other guidelines. However, we recommend the presentation of the resource use with both natural and monetary units. This information on natural units can be useful as some components, such as human resources, might not even be under the control of the budget holder. For example, a district programme manager may be the budget holder but yet may not have control over the recruitment for additional personnel.

Strengths

To best of our knowledge, this is the first set of BIA recommendations for India. Our BIA guidance principles are an improvement over the existing guidelines. First, most of the existing guidance is related to the conduct of pharmaceutical BIAs (e.g., Polish, Canadian, Belgian, Brazilian and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] Guidelines) [31]. However, our recommendations are a set of robust guidelines which can be used to assess drugs, health technologies as well as health programmes. Second, the majority of available recommendations are applied in either an insurance-based (e.g., Belgium, France, Poland, Netherlands) or a supply-side financed health system (Ireland, Canada, Brazil) [31]. However, for India, it is of utmost importance to address the intricacies of the system, which have been well addressed. Another strength to our recommendations is the participation of the users, i.e., those responsible for the allocation of resources. This not only adds to its credibility but also encourages the utilisation of this tool to inform decision making. Finally, the availability of BIA guidelines will improve the utilisation of this tool for sustainable allocation of resources.

Limitations

The implications of both BIA and CEA should be carefully considered together to allow sustainable allocation of resources. Evidence from BIA should be meticulously assessed alongside the information on how the budgetary expenses have to be met. There is a need to differentiate the budgetary requirement for an intervention which may either require additional allocation of resources or a redistribution of existing funding. In the former scenario, where additional investment is allocated, the implication of BIA is straightforward and will depend on the capacity of fiscal space to accommodate the budgetary requirement for the intervention. For the latter, if redistribution of current allocation is required, the displacement of funds will thus imply an opportunity cost in terms of some existing benefits to be forgone in order to deliver the intervention. In such a situation, the evidence from CEA, which measures the opportunity cost of resource allocation, would become even more important. In such a scenario, there would be a limitation to the extent to which BIA evidence can inform the overall implications of additional monetary requirement for implementing the evidence.

Utility of BIA for Deriving Thresholds

Another unresolved issue lies around the estimation of thresholds required to interpret the results of a CEA. Earlier, the WHO’s Commission on Macroeconomics and Health suggested the use of 1- to 3-times the GDP per capita as the threshold [50]. However, the revised guidance by WHO pertaining to interpretation of cost-effectiveness thresholds (CET) suggests that 1- to 3-times the GDP per capita threshold criteria should not be used as a decision rule, but rather should be considered a guide to policy makers to assess value for money [51]. In addition, WHO recommends that an intervention should also be assessed in terms of affordability, budget impact, fairness, feasibility and any other criteria considered important in the local context [51]. In the absence of defined thresholds, one can assess the willingness to pay (WTP) or the health opportunity costs to guide decision making. However, another approach could be the use of league tables [51, 52]. This approach relies on attaining the largest health impact for the given budget, where one can compare the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios across the available budget. In absence of explicit thresholds, BIA can complement the findings from a CEA to provide pragmatic evidence for decision making.

Conclusion

Our recommendations for the conduct of BIA aim to promote consistency and transparency in the conduct as well as reporting of the analysis. This will ensure comparability of estimates across BIA studies of different interventions, which will enhance the utility of BIA for decision making. Second, application of a comprehensive understanding of the newer health interventions or programmes, both in terms of its financing and delivery, would be central to the robustness of BIA evidence. However, evidence from BIA should be considered carefully alongside the information on how the budgetary expenses have to be met, i.e., whether additional resources are available or whether it involves a re-allocation of existing resources which has opportunity cost implications. Both BIA and CEA are independent tools which aid the process of informed decision making. In addition, BIAs complement the results of economic evaluations. Thus, these are not to be considered a substitute to each other. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as India, the CEA evidence could serve as a potential tool for advocacy as several known cost-effective interventions have poor coverage. Similarly, the BIA evidence could serve to aid pragmatic decision making for sustainable financing of healthcare.

Acknowledgements

We are highly grateful to members of Technical Appraisal Committee (TAC), Technical partners, Regional Resource Centres (RRCs) of Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn), policy makers and programme managers who provided their valuable inputs and feedback during the development of guidelines. We are also thankful to Ms. Maria De Francesco, Imperial College, London for the conduct of the systematic review of Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) guidelines which preceded the development of Indian BIA guidelines, as well as her inputs on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Declarations

Funding

This study was supported by a grant received from the Department of Health Research, Government of India (Grant number: No. T 11011/02/2017-HR).

Conflict of interest/Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Consent to participate

Verbal and e-mail informed consent was obtained from participants who provided feedback in the process of guidelines development.

Consent for publication

The corresponding author has obtained consent of all authors for publication of this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

All the required data are mentioned in the text of the manuscript.

Code availability

Not Applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SP, YC, KR, VRM; data curation: SP, YC; methodology: SP, YC; formal analysis and investigation: SP, YC; project administration: KR; supervision: SP, KR, VRM; validation: KR, VRM; writing—original draft preparation: YC, SP; writing—review and editing: SP, KR, VRM.

References

- 1.Bilinski A, Neumann P, Cohen J, Thorat T, McDaniel K, Salomon JA. When cost-effective interventions are unaffordable: integrating cost-effectiveness and budget impact in priority setting for global health programs. PLoS Med. 2017;14(10):e1002397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghabri S, Mauskopf J. The use of budget impact analysis in the economic evaluation of new medicines in Australia, England, France and the United States: relationship to cost-effectiveness analysis and methodological challenges. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;19(2):173–174. doi: 10.1007/s10198-017-0933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chugh Y, Dhiman RK, Premkumar M, Prinja S, Grover GS, Bahuguna P. Real-world cost-effectiveness of pan-genotypic Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir combination versus genotype dependent directly acting anti-viral drugs for treatment of hepatitis C patients in the universal coverage scheme of Punjab state in India. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e022176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teerawattananon Y, Tritasavit N, Suchonwanich N, Kingkaew P. The use of economic evaluation for guiding the pharmaceutical reimbursement list in Thailand. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2014;108(7):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Universal Health Coverage | National Health Portal Of India. Nhp.gov.in. 2020. https://www.nhp.gov.in/universal-health-coverage_pg. Accessed 23 Feb 2020.

- 6.Angell BJ, Prinja S, Gupt A, Jha V, Jan S. The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana and the path to universal health coverage in India: Overcoming the challenges of stewardship and governance. PLoS Med. 2019;16(3):e1002759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Policy. Nhp.gov.in. 2020. https://www.nhp.gov.in/nhpfiles/national_health_policy_2017.pdfHome. Accessed 6 Jun 2020 | Ayushman Bharat | National Health Authority | GoI. Pmjay.gov.in. 2020. https://www.pmjay.gov.in/. Accessed 24 Feb 2020.

- 8.Bhatia V, Sahoo D. India's commitment towards global vision: Universal health coverage. Indian J Commun Family Med. 2018;4(1):2. doi: 10.4103/2395-2113.251343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Home | Ayushman Bharat | National Health Authority | GoI. Pmjay.gov.in. 2020. https://www.pmjay.gov.in/. Accessed 24 Feb 2020.

- 10.Kumar M, Taylor FC, Chokshi M, Ebrahim S, Gabbay J, Taylor FC. Health technology assessment in India: the potential for improved healthcare decision-making. Natl Med J India. 2014;27(3):149–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prinja S, Downey LE, Gauba V, Swaminathan S. Health technology assessment for policy making in India: current scenario and way forward. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;2(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s41669-017-0037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downey LE, Mehndiratta A, Grover A, Gauba V, Sheikh K, Prinja S, Singh R, Cluzeau FA, Dabak S, Teerawattananon Y, Kumar S, Swaminathan S. Institutionalising health technology assessment: establishing the Medical Technology Assessment Board in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000259. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health Research. Health Technology Assessment in India: A Manual. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018.

- 14.Mauskopf JA, Sullivan SD, Annemans L, Caro J, Mullins CD, Nuijten M, et al. Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices—budget impact analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(4):336–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, Caro JJ, Lee KM, Minchin M, et al. Budget impact analysis—principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall DA, Douglas PR, Drummond MF, Torrance GW, Macleod S, Manti O, et al. Guidelines for conducting pharmaceutical budget impact analyses for submission to public drug plans in Canada. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(6):477–494. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of economic appraisal 2013. 2013. http://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg9/resources/non-guidance-guide-to-themethods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2016. [PubMed]

- 18.Neyt M, Cleemput I, Van de Sande S, Thiry N. Belgian guidelines for budget impact analyses. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;70:174–180. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira-Da-Silva AL, Ribeiro RA, Santos VC, Elias FT, d’Oliveira AL, Polanczyk CA. Proposal of Brazilian guidelines for conducting budget impact analysis for health technologies. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28(7):1223–1238. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2012000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batta RN. Public health management in India: concerns and options. J Public Adm Policy Res. 2014;7(3):40–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta I, S Chowdhury. Financing for Health Coverage in India—Issues and Concerns”. IEG Working Paper No. 346. 2015; Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi, India.

- 22.Prinja S, Kaur M, Kumar R. Universal health insurance in India: ensuring equity, efficiency, and quality. Indian J Commun Med. 2012;37(3):142. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.99907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman P, Ahuja R, Tandon A, Sparkes S, Gottret P (2010) Government Health Financing in India: Challenges in Achieving Ambitious Goals. Washington, DC: World Bank Human Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper 59886.

- 24.NSSO | Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation | Government Of India [Internet]. Mospi.gov.in. 2020. http://www.mospi.gov.in/nsso. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 25.National Health Accounts Technical Secretariat, National Health Systems Resource Centre. National Health Accounts Estimates for India. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2019 p. 80.

- 26.Prinja S, Kaur M, Kumar R. Universal Health Insurance in India: ensuring equity, efficiency and quality. Indian J Commun Med. 2012;37(3):142–149. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.99907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma A, Prinja S. Universal health coverage: current status and future roadmap for India. Int J Non-Communicable Dis. 2018;3(3):78. doi: 10.4103/jncd.jncd_24_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis RP, McGuire TG. Supply-side and demand-side cost sharing in health care. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1993;7(4):135–151. doi: 10.1257/jep.7.4.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Gupta I, Chowdhury S, Trivedi M. Role of insurance in determining utilization of healthcare and financial risk protection in India. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta I, Joe W, Rudra S. Demand side financing in health how far can it address the issue of low utilization in developing countries? World health report background paper no. 27. 2010, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 31.Chugh Y, De Francesco M, Prinja S. Systematic literature review of guidelines on budget impact analysis for health technology assessment. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;6:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40258-021-00652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey A, Ploubidis GB, Clarke L, Dandona L. Trends in catastrophic health expenditure in India: 1993 to 2014. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(1):18. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.191759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prinja S, Singh MP, Rajsekar K, et al. Translating research to policy: setting provider payment rates for strategic purchasing under India's National Publicly Financed Health Insurance Scheme. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prinja S, Singh MP, Guinness L, et al. Establishing reference costs for the health benefit packages under universal health coverage in India: cost of health services in India (CHSI) protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035170. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh P, Tatambhotla A, Kalvakuntla R, Chokshi M. Understanding public drug procurement in India: a comparative qualitative study of five Indian states. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001987. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.TNMSC: Drug Procurement Policy-Tamil Nadu Medical Service Corporation. http://www.tnmsc.com/tnmsc/new/html/Procurement%20&%20Tender.php. Accessed 20 May 2021.

- 37.Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Tripathy JP, Kumar R. Availability of medicines in public sector health facilities of two North Indian States. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40360-015-0043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Census of India: Sample Registration [Internet]. Censusindia.gov.in. 2020. https://censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/srs/sample_registration_system.aspx. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 39.National Family Health Survey [Internet]. Rchiips.org. 2020 http://rchiips.org/nfhs/. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 40.District Level Household & Facility Survey [Internet]. Rchiips.org. 2020. http://rchiips.org/. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 41.Niti Aayog. Heathy States: Progressive India. World Bank Res News [Internet]. 2018.

- 42.Government of India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Home: Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP) [Internet]. Idsp.nic.in. 2020. https://idsp.nic.in/. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 43.HMIS-Health Management Information System [Internet]. Hmis.nhp.gov.in. 2020. https://hmis.nhp.gov.in/#!/. Accessed 4 Jul 2020.

- 44.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Health Mission . Framework for Implementation, 2012–2017. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2014. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U, Kuntz KM. Modeling good research practices—overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force–1. Med Decis Making. 2012;32(5):667–677. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12454577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9764):505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atun RA, Bennett S, Duran A, World Health Organization . When do vertical (stand alone) programmes have a place in health systems? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berman P, Bhawalkar M, Jha R. Government financing of health care in India since 2005: What was achieved, what was not and why. A Report of the Resource Tracking and Management Project Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA. 2017.

- 50.Marseille E, Larson B, Kazi DS, Kahn JG, Rosen S. Thresholds for the cost–effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;14(93):118–124. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.138206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bertram MY, Lauer JA, De Joncheere K, Edejer T, Hutubessy R, Kieny MP, Hill SR. Cost–effectiveness thresholds: pros and cons. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(12):924. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.164418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Culyer T. Cost-effectiveness thresholds in health care: a bookshelf guide to their meaning and use. Health Economics Policy Law. 2016;11(4):415–432. doi: 10.1017/S1744133116000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]