Abstract

Purpose:

There were approximately 37.9 million persons infected with HIV in 2018 globally, resulting in 770,000 deaths annually. Over 50% of this infection and deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, with countries like Nigeria being seriously affected. Nigeria has one of the highest rates of new infections globally. To control HIV infection in Nigeria, there is a need to continually screen high-risk groups for early HIV infection and subtypes using very sensitive methods. In this study, new HIV-1 infection and circulating HIV-1 subtypes among febrile persons and blood donors were determined. Performance characteristics of three commercial EIA kits were also evaluated.

Methods:

In total, 1028 participants were recruited for the study. New HIV-1 infection and subtypes were determined using enzyme immunoassays and molecular techniques, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and agreements were compared among the EIA kits using PCR-confirmed HIV-positive and negative samples.

Results:

The overall prevalence of HIV infection in this study was 5.35%. The rate of new HIV infection was significantly different (p < .03674) among 1028 febrile persons (Ibadan: 2.22%; Saki: 1.36%) and blood donors (5.07%) studied. Three subtypes, CRF02_AG, A, and G, were found among those with new HIV infection. Whereas the commercial ELISA kits had very high specificities (94.12%, 100%, and 100%) for HIV-1 detection, Alere Determine HIV-1 antibody rapid kit had the lowest sensitivity score (50%).

Conclusion:

Genetic diversity of HIV-1 strains among infected individuals in Oyo State, Nigeria, is still relatively high. This high level of diversity of HIV-1 strains may impact the reliability of diagnosis of the virus in Nigeria and other African countries where many of the virus strains co-circulate.

Keywords: CRF02_AG, ELISA, High-risk groups, HIV-1 rapid kits, HIV-1 subtypes

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In 2018, about 37.9 million persons were infected with HIV globally, with 21% of these people not aware of their status.1 Also, in the same year, 770,000 AIDS-related deaths occurred and 1.7 million (4.4%) individuals became newly infected with the virus. Over 50% of HIV infection and AIDS-related deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, making the region the highest hit with the infection.1 Although the rate of HIV infection is controlled in the general population in most countries in Africa, there is still a high prevalence of the virus among the high-risk groups such as commercial sex workers, voluntary blood donors, etc. To control the HIV epidemic and achieve the 95-95-95 target (95% of people living with HIV diagnosed, 95% of these people on treatment, and 95% of those on treatment virologically suppressed by 2030),2 it is important that new HIV infections are quickly diagnosed and high-risk groups are continuously identified and monitored.3 Furthermore, it is pertinent that circulating subtypes within these groups are determined, because previous studies have shown that HIV-1 subtypes have differing impacts on diagnosis, transmission, pathogenesis, and vaccine designs.4–6

In Nigeria, over 1.9 million people are infected with HIV and around 33% of these people do not know their status. Although recent surveys have shown a reduction in the prevalence of HIV infection, the country still has one of the highest number of new HIV infections (130,000) and AIDS-related deaths (53,000) globally, due to its large population.1 Diverse HIV-1 subtypes and recombinant forms (CRF02_AG, G, A, B, C, D, CRF06_cpx, URFs, etc.) have been previously characterized in the country.7 Several HIV-1 high-risk groups such as commercial sex workers,8,9 voluntary blood donors,10,11 long-distance drivers,12–14 mammy markets contiguous to military facilities,15 etc., have also been identified.

In a previous study, we identified persons with febrile symptoms such as those referred for malaria tests as a group to be screened for early HIV infection.16–18 Most of these individuals are unaware of their status; hence, they pose an even higher transmission risk. Also, in most pre-donation blood screening centers in the country, HIV-1 rapid antibody kits are used for HIV infection diagnosis.19,20 These assays are unable to detect infected persons at the early stages of infection. To sustain the gains of HIV control in the country, there is a need to diagnose persons at the early stages of HIV-1 infection as well as monitor the prevalence of the infection among high-risk groups like voluntary blood donors. Voluntary blood donors may fuel the spread of the virus, as there is still a high prevalence of unscreened or improperly screened HIV-infected blood in Nigeria and other developing countries.21,22

Despite concerted efforts in the country to control HIV infection, an appreciable number of persons do not know their status and there are very limited data on circulating HIV-1 subtypes among febrile persons and voluntary blood donors. Although opportunities for HIV-1 testing have improved in the country, most testing centers use HIV-1 rapid antibody devices for diagnosis.23 These kits increase access by reducing turnaround time, but their usefulness in eliminating samples with HIV-1 antibodies during early HIV infection diagnosis is not known. It is uncertain whether the sensitivity of these kits is not reduced in areas with high HIV-1 prevalence and diverse HIV-1 subtypes. This study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of early HIV infection as well as the circulating subtypes among voluntary blood donors and febrile persons attending hospitals in Ibadan and Saki, Oyo State, Nigeria. The performance characteristics of an HIV rapid antibody point-of-care test kit (Alere Determine HIV-1/2 set) for HIV-1 antibody detection were also determined.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study sites and population

This study was conducted in two major cities in Oyo state, Nigeria, namely Ibadan and Saki, as previously described.16 Ibadan is the capital city of Oyo State, with a population of about 7 million people, whereas Saki is a semiurban community 100 miles Northwest of Ibadan, close to the border with the Republic of Benin. Multiple HIV-1 subtypes and circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) have been previously shown to be circulating in these two cities.24 Samples were collected in government, missionary, and private hospitals in these cities that were selected on the basis of accessibility and availability of resident Physicians and Laboratory Staff. Most of the samples were collected from government-owned primary and secondary health facilities because services in these hospitals for outpatients were provided at little or no cost. Voluntary blood donors, as well as febrile persons referred by Clinicians for malaria antigen test from selected hospitals in Ibadan and Saki, were recruited into the study.

2.2 |. Recruitment of participants, sample collection, and processing

This study was an extension of a pilot study conducted in 2015. Initial findings from the study have been previously reported.16 Participants were recruited for this study after obtaining their informed consent. Their demographic information, such as age, sex, and contact details, were collected. Individuals infected with HIV were counseled and integrated into existing HIV/AIDS management and treatment centers closest to them. On the whole, 1028 participants were enrolled in the study, including 890 febrile persons and 138 voluntary blood donors. Patients with febrile illness were enrolled from Ibadan and Saki, whereas blood donors were from a tertiary hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. Five milliliters of whole blood were collected in EDTA bottles from each participant. Plasma was separated from the samples (after centrifugation at 3500RPM for 5 min) immediately after collection and stored at −20°C until transported under cold chain condition to the Department of Virology, University College Hospital, where they were stored at −80°C until analyzed. Blood samples were analyzed for HIV antigen/antibody using commercially available ELISA kit and HIV-1 Gag DNA, as previously described.16

2.3 |. Identification of new and chronic HIV-1 infections

The updated CDC algorithm of laboratory testing for the diagnosis of early and chronic HIV-1 infection was used for this study, as previously described.16 Briefly, samples were identified as early HIV infection if HIV-1 DNA was detected after being positive with a fourth-generation HIV ELISA that can detect both antigen and antibody and negative with third-generation HIV ELISA that detects only HIV antibody. Those with positive HIV-1 DNA, as well as both fourth- and third-generation ELISA, were classified as chronic HIV infection. Genscreen ULTRA HIV Ag–Ab ELISA kit (Biorad, Hercules, California) and AiD anti-HIV 1 + 2 ELISA kit (Wantai) were used as the fourth- and third-generation ELISA kits, respectively. The Genscreen ULTRA HIV Ag–Ab ELISA kit detects HIV P24 antigen as well as gp41 and gp36 envelope antibodies to HIV-1 (groups M and O) and HIV-2 subtypes, whereas the AiD anti-HIV 1 + 2 ELISA kit is intended for the qualitative detection of antibodies to HIV-1 (groups M and O) and HIV-2 subtypes. The assays were performed under strict biosafety conditions and according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, and there were no cross-contamination or invalid results during analysis. All samples collected from recruited participants (n = 1028) were tested on the two ELISA kits. HIV-1 antibodies using Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Rapid Antibody Test Kit (HIV Rapid Ab POC) (Alere) was tested in a subset of the samples (n = 671). The testing flow chart is shown in Figure 1. Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Rapid Antibody Test Kit is designed to rapidly detect antibodies to HIV-1 and 2 subtypes in human blood. The test kits used in this study have been approved for use in most developing countries.

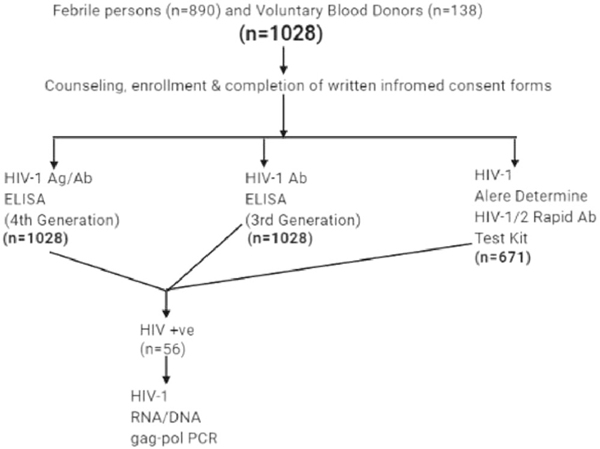

FIGURE 1.

Diagram showing the testing flow chart. Values are shown in numbers only. A total of 1028 persons were recruited for the study after obtaining informed consent. In total, 890 were febrile persons, whereas 138 were voluntary blood donors. All (n = 1028) samples were tested on Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab and AiD anti-HIV-1/2 ELISA kits. A subset of the samples (n = 671) was tested on Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Rapid Antibody. All HIV-positive samples (n = 56) were further confirmed on PCR

2.4 |. PCR amplification and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from the whole blood sample using guanidium thiocyanate in-house protocol.16 A fragment of the Gag-Pol region (900 base pairs) of the virus was amplified using previously published primers and cycling conditions25 with slight modifications. Briefly, PCR was performed using a SuperScript III One-step RT-PCR system with platinum TaqDNA High-fidelity polymerase (Jena Bioscience). Each 25-μl reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl reaction mix (2×), 4.5 μl RNase-free water, 1 μl each of each primer (20pmol/μl), 1 μl Superscript III RT/Platinum Taq High-Fidelity mix, and 5 μl of template DNA. Pan-HIV-1_1R (CCT CCA ATT CCY CCT ATC ATT TT) and Pan-HIV-1_2F (GGG AAG TGA YAT AGC WGG AAC) were used. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, 68°C for 1 min 30 s, and, finally, 68°C for 10 min.

Another set of Gag primers26 was used for samples that were undetectable using Pan-HIV1_1R and Pan-HIV-1_2F. Briefly, a 700-bp fragment corresponding to the p24 region was amplified using G00 and G01 for the first round and G60-G25 for the second round. The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step for 3 min at 92°C, followed by 30 cycles of 92°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. Amplicons were detected by gel electrophoresis. Furthermore, HIV-1 VIF gene of samples whose GAG genes were unsequenceable was detected and sequenced. As described previously,27 the use of Vif-1 (ATTCAAAATTTTCGGGTTTATTACAG) and TATED3-1 (AATTCTGC AACAACTGCTGTTTAT) primers for first round and Vif-2 (AGGT GAAGGGGCAGTAGTAATACA) and TATED-1(GCAGGAGTGGAAG CCATAATAAG) primers for second-round PCR gave a 600-bp fragment. The cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min, with a final extension for 4 min at 68°C for 1 min. Amplicons with the expected product size were shipped on ice to Macrogen, South Korea, for Big Dye sequencing using the same second-round PCR forward and reverse (amplification) primers (Pan-HIV-1_1R and Pan-HIV-1_2F; or G60 and G25; or Vif-2 and TATED-1 for VIF).

2.5 |. Genotyping of HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants

The sequences were cleaned and edited using Chromas and Bioedit softwares. Subtyping was performed using a combination of four subtyping tools: The Rega HIV-1 Subtyping Tool, version 3.0 (http://dbpartners.stanford.edu/RegaSubtyping/), Comet, version 2.2 (http://comet.retrovirology.lu), National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and jpHMMM, improving the reliability of recombination prediction in HIV-1 (http://jphmm.gobics.de/submission_hiv). The first three tools were used simultaneously, whereas jpHMMM was used to resolve discordant subtypes. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA software version 10. Alignment of sequences was performed using MAFFTS online software. Genetic distances were inferred using the Tamura–Nei model and a phylogenetic tree was generated using the maximum likelihood method. The robustness of the tree was evaluated with 1000 bootstrap replicates. All consensus nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were submitted to GenBank database and assigned accession numbers MN943617–635.

2.6 |. Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital (UI/UCH) Research and Ethics Committee (UI/EC/15/0076) and the Oyo State Ministry of Health Committee on Human Research (AD13/479/951). All results were delinked from patient identifiers and anonymized.

2.7 |. Eligibility/exclusion criteria

Only individuals aged 18–65 years were included in the study. Individuals who already knew their HIV status were excluded from the study.

2.8 |. Data management and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, SPSS version 20, and GraphPad prism. Categorical variables were compared using Z and chi-square tests, whereas quantitative variables were compared using ANOVA. Test of significance was set at p < .05. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive percent agreement, and Cohen Kappa were calculated to determine the performance characteristics of each assay with the HIV positives in a polymerase chain reaction, as previously described.28–30 The number and percentage of positive results were used to summarize data for each assay.

A concordance assessment between the ELISA kits was conducted to assess the agreement between the kits. These concordance measures included overall, positive, and negative percent agreement, as well as Cohen’s kappa statistic. These measures are standard and robust metrics used to estimate the level of agreement beyond chance between two diagnostic tests. Kappa values were graded as previously described.28 The values ranged between 1 and 100 (in percentages), with a ≤40 denoting poor agreement, 40–75 denoting fair/good agreement, and ≥75 denoting excellent agreement. The significance level indicated at 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported for each metric. The McNemer chi-squared test was also used to calculate the significance of the performances of ELISA kits.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient characteristics

In total, 1028 individuals participated in this study, of which 890 (86.5%) febrile persons were referred for malaria antigen testing. Voluntary blood donors were recruited only in Ibadan. Also, 594 (57.7%) of these individuals were female. The mean (±SD) ages for febrile patients in Ibadan, Saki, and voluntary blood donors were 37.2 (±9.1), 36.1 (±14.3), and 35.1 (±14.3) years, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of new and chronic HIV-1 infection among febrile persons and voluntary blood donors

| Febrile persons# | Voluntary blood donors# | Total | p value/test# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Ibadan | Saki | Subtotal | Ibadan | Total | p value/test |

| Number of participants | 450 | 440 | 890 | 138 | 1028 | p < .00001/Z |

| Number (%) HIV+ | 29 (6.44) | 17 (3.86) | 46 (5.16) | 9 (6.52) | 55 (5.35) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Number (%) chronic HIV+ | 19 (4.22) | 11 (2.5) | 30 (3.37) | 2 (1.44) | 32 (3.11) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Number (%) early HIV+ | 10 (2.22) | 6 (1.36) | 16 (1.36) | 7 (5.07) | 23 (2.23) | p < .03674/χ2 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Total number tested | 450 | 440 | 890 | 138 | 1028 | |

| Men\women | 168/282 | 130/310 | 298/592 | 136/2 | 434/594 | p < .0001/Z |

| Number (%) HIV+ | 29 (6.44) | 17 (3.86) | 46 (5.16) | 9 (6.52) | 55 (5.35) | |

| Men (%) HIV+ | 14 (48.27) | 5 (29.4) | 19 (41.3) | 9 (100) | 28 (50.90) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Women (%) HIV+ | 15 (51.72) | 12 (70.5) | 27 (58.6) | 0 (0) | 27(49.09) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Number (%) chronic HIV + | 19 (4.22) | 11 (2.5) | 30 (3.37) | 2(1.44) | 32 (3.11) | |

| Men (%) HIV+ | 10 (52.63) | 4 (36.3) | 14 (46.6) | 2 (100) | 16 (50.00) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Women (%) HIV+ | 9 (47.37) | 7 (63.6) | 16 (53.3) | 0(0) | 16 (50.00) | |

| Number (%) early HIV+ | 10 | 6(1.4) | 16 (1.36) | 7 (5.07) | 23 (2.23) | |

| Men (%) HIV+ | 4 (40.00) | 1 (16.6) | 5 (31.25) | 7 (100) | 12 (52.17) | p > .05/χ2 |

| Women (%) HIV+ | 6 (60.00) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (68.75) | 0 (0) | 11 (47.82) | |

Values shown are in number and percentages. Statistical tests used: Z and chi-square (χ2) tests. Significant differences are in bold fonts, whereas differences that are not significant are written as p > .05.

p value/test shows value and test of significance used for comparing differences between febrile persons and voluntary blood donors

3.2 |. Prevalence of new and chronic HIV infection

A total of 55 persons were HIV-positive, giving an overall rate of infection of 5.35%. HIV prevalence varied by location and groups tested. Twenty-three (2.23%) individuals were at the early stages of HIV infection, with a higher rate among voluntary blood donors (5.07%) as compared with febrile persons (Ibadan: 2.22%; Saki: 1.36%) (p < .03674). Differences in prevalence by sex were not significant for either early or chronic HIV infection (Table 1). However, a higher percentage of females were infected with HIV when compared with males. Only two of the blood donors were females (1.4%) and none of them were positive for HIV.

3.3 |. Performance characteristics of serological assays

As shown in Tables 2a and b, sensitivity (98.21%, 57.14%, 50%), negative predictive values (99.9%, 97.59%, 97.56%), and positive (99.10%, 72.73%, 98.69%) and negative (99.95%, 98.78%, 65.31%) percent agreements were highest in Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab and lowest in the Alere Determine rapid kits. However, specificity (100%, 100%, 99.84%) and positive (100%, 100%, 94.12%) predictive value were the same for Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab ELISA and AiD anti-HIV-1/2 ELISA kits. The kits had good agreements, although Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab ELISA and the AiD anti-HIV-1/2 ELISA showed excellent agreements. The antibody-based kits also showed excellent overall agreements. The performance characteristics of the three EIA kits are also presented. As shown in Figure 1, 14 samples were reactive for antiHIV antibodies on all serological assays, whereas no sample was reactive on HIV Ab ELISA alone or on HIV Ab ELISA and HIV Rapid Ab POC. Eight samples with detectable anti-HIV antibodies (1.2%) were undetectable by HIV rapid Ab POC.

TABLE 2a.

Diagnostic assessment of serological kits against reference standard (PCR)

| Kit | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | Positive predictive value % (95% Cl) | Negative predictive value % (95% Cl) | Positive percent agreement % | Negative percent agreement % | Cohen’s Kappa k (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab | 98.21 (90.45–99.95) | 100 (99.62–100) | 100 | 99.9 (99.29–99.99) | 99.10 | 99.95 | 99.05 (97.18–100) |

| AiD anti-HIV-1/2 | 57.14 (43.22–70.29) | 100 (99.62–100) | 100 | 97.59 (96.77–98.21) | 72.73 | 98.78 | 71.60 (60.84–82.37) |

| Alere determine HIV-1/2 | 50 (31.89–68.11) | 99.84 (99.13–100) | 94.12 (68.65 to 99.15) | 97.56 (96.58–98.26) | 98.69 | 65.31 | 64.12 (48.37–79.87) |

Values shown are in numbers and percentages. K values ranged between 1 and 100 (in percentages) with a ≤40 denoting poor agreement, 40–75 denoting fair/good agreement, and ≥75 denoting excellent agreement. The significance level indicated at 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported for each metric. All positive samples on fourth- and third-generation ELISA were confirmed by PCR as positives.

Only HIV Ab POC test had one false-positive result.

TABLE 2b.

Concordance assessment between diagnostic kits

| Test | Compared with | Overall percent Agreement | Positive percent Agreement | Negative percent Agreement | Cohen’s Kappa k (95% Cl) | Mcnemer chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genscreen ULTRA HIV-1 Ag/Ab ELISA | AiD anti-HIV-1/2 ELISA | 99.10 | 83.02 | 99.54 | 82.57 (71.41 to 93.73) | p = .0077 |

| Alere determine HIV-1/2 | 97.47 | 63.83 | 98.69 | 62.66 (46.36 to 78.95) | p = .0007 | |

| AiD anti-HIV-1/2 ELISA | Alere™ determine HIV-1/2 | 98.64 | 75.68 | 99.30 | 75.00 (59.28 to 90.73) | p = .0455 |

Values shown are in numbers and percentages. K values ranged between 1 and 100 (in percentages) with a ≤40 denoting poor agreement, 40–75 denoting fair/good agreement, and ≥75 denoting excellent agreement. The significance level indicated at 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported for each metric. The McNemer Chi-squared test was also used to calculate the significance of the performances of ELISA kits.

3.4 |. Subtyping

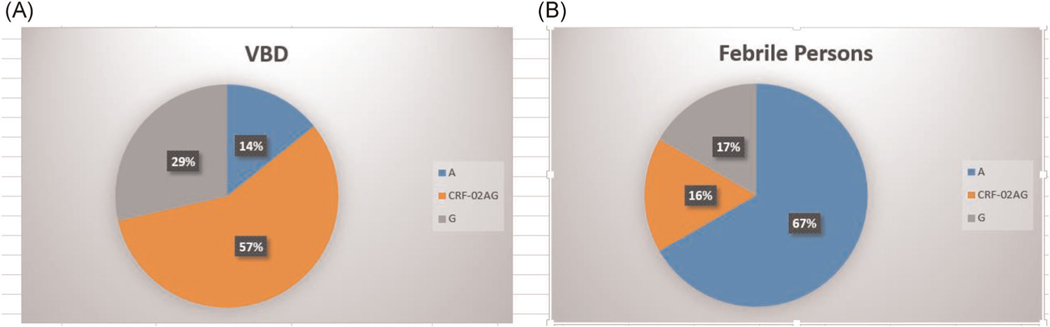

Here, 20 out of the 23 isolates from persons with recent HIV infection were successfully sequenced out, of which 13 were from febrile persons and 10 from voluntary blood donors. Also, 7 out of the 13 isolated from febrile persons have been previously reported.16 We report in this study 13 new isolates from persons at the early stages of HIV infection, 7 were from voluntary blood donors and the rest were from febrile persons. Table 3 shows the subtypes and recombinants identified in this study. Three subtypes, CRF02_AG, A, and G were found among those with new HIV infection, with CRF02_AG and A being the predominant subtypes. CRF02AG and subtype A were the most predominant strains among voluntary blood donors (4; 57.14%) and febrile persons (4; 66.6%), respectively (Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Subtype classification of HIV-1 GAG gene isolated from individuals with new infection

| Status | Sequence ID | Accession number | Assigned subtype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Febrile persons | EHIV010 | MN943617 | A |

| Febrile persons | EHIV011 | MN943616 | A |

| Febrile persons | EHIV012 | MN943624 | G |

| Febrile persons | EHIV013 | MN943613 | A |

| Febrile persons | EHIV014 | MN943628 | CRF02-AG |

| Febrile persons | EHIV015 | MN943615 | A |

| VBD | EHIV016 | MN943627 | G |

| VBD | EHIV017 | MN943629 | CRF02-AG |

| VBD | EHIV018 | MN943633a | CRF02-AG |

| VBD | EHIV019 | Not Sequenced | |

| VBD | EHIV020 | MN943634a | CRF02-AG |

| VBD | EHIVO21 | MN943635a | CRF02-AG |

| VBD | EHIV022 | MN943625 | G |

| VBD | EHIV023 | MN943619 | A |

VIF gene was sequenced

Letter a in superscript corresponds to samples that the GAG gene was not sequenced, rather the VIF gene was sequenced and used for subtyping.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of subtypes isolated from individuals with new HIV-1 infection. Values are shown in percentages only. (A) A pie chart showing the distribution of subtypes isolated from voluntary blood donors. The total number of individuals in this group is 8. One sample was not sequenced. Also, 4, 2, and 1 samples were subtyped as CRF-02 AG, G, and A, respectively. (B) A pie chart showing the distribution of subtypes isolated from febrile persons. The total number of individuals in this group is 6. Also, 4, 1, and 1 samples were subtyped as A, CRF-02 AG, and G, respectively

3.5 |. Phylogenetic analysis

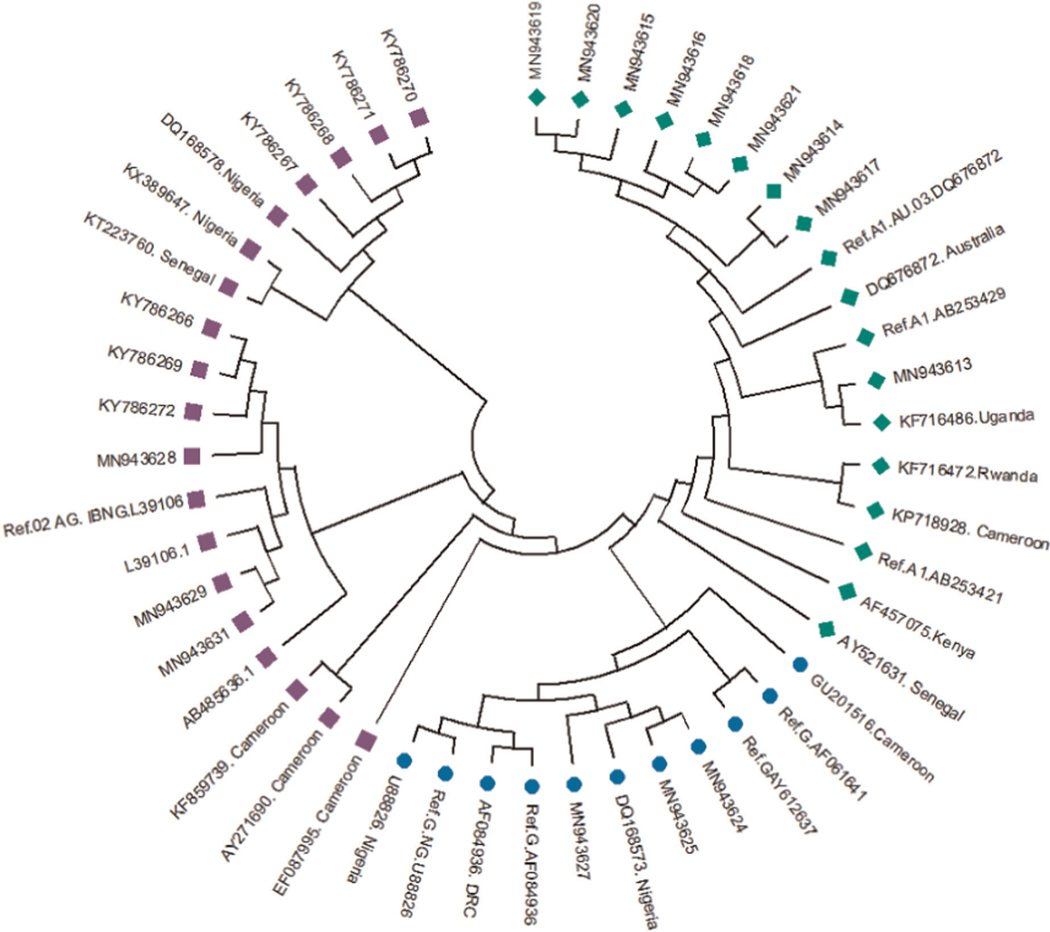

Figure 3 shows the estimated phylogeny of HIV-1 subtypes with respect to reference sequences available in the HIV Los Alamos National HIV Sequence database. As shown in Figure 3, Subtypes A, G, and CRF02_AG were identified with green, blue, and pink symbols, respectively. HIV-1 subtypes A identified in this study were closely related to Ref A1 DQ676872 as well as subtypes AF457075, KF716486, and AY521631 from Kenya, Uganda, and Senegal, respectively. Those identified as subtypes G and CRF02-AG were closely related to the Nigerian subtypes DQ168573 and Ref.02 AG IBNG. L39106, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the P17/P24 regions of the GAG gene of HIV-1. Reference subtypes are indicated with Ref. before their accession numbers. Other sequences are indicated with their accession numbers and country of isolation. Subtypes obtained from samples in this study are indicated with their accession numbers only. Subtypes A, G, and CRF02_AG were identified with green diamond, blue circle, and pink square symbols, respectively. Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree were constructed using MAFFTS and Maximum Parsimony algorithm in MEGA 6 software. Statistical significance of the tree topology was tested by 1000 bootstrap replication

4 |. DISCUSSION

The overall rate of new HIV infection obtained in this study is 2.23%. This is higher than the prevalence of HIV-1 in Nigeria, which is about 1.9%.1 This rate is also higher than previously reported in similar studies carried out in Nigeria31 and other parts of Africa.17,32 This may be due to the method used for determining new HIV infections. For example, a previous study in Nigeria that characterized acute HIV-1 infection among high-risk groups used HIV-1 rapid antibody kit to eliminate seroconversion.33 Furthermore, the study population can also play a role in the high prevalence observed in this study. Blood donors were screened in this study, whereas most of the previous studies have only focused on febrile persons and other groups that are known to have lower HIV prevalence as compared with blood donors.

As rapid antibody kits are used as predonation screening tests in Nigeria and other African countries,19 infected blood donors at the early stages of infection may be missed. Although blood samples are re-tested with more sensitive ELISA kits before transfusion, most blood donors are not aware of their status until a later time, that is, if they are eventually contacted. Besides this, these persons can easily transmit this virus to other susceptible persons. The blood donation program in some health facilities works just like the voluntary counseling and testing center where the use of rapid kits is encouraged.

The prevalence of new HIV-1 infection was higher among voluntary blood donors (5.07%) as compared with febrile persons (Ibadan: 2.22%; Saki: 1.36%). Screening high-risk groups for HIV infection will positively impact the control of new infections in Nigeria and Sub-Saharan Africa.34 To effectively control the prevalence and incidence of HIV-1 infection in the country, it is important that persons at the early stages of infection are identified and placed under treatment early. Identifying and treating HIV-1-infected individuals during the early stages of infection will go a long way in reducing new HIV-1 infections as well as in decreasing the number of AIDS-related deaths in the country, as undetectable equals untransmittable.35

Results of the overall HIV-1 prevalence among febrile persons (5.16%) in this study is very similar to what was obtained from our previous study among persons referred for malaria antigen test (4.1%).16 Furthermore, our result on the prevalence of HIV-1 infection among blood donors (5.35%) is also similar to previous studies on this group that used ELISA-based tests for diagnosis.10,22,36 Besides the fact that various regions in the country have varying HIV-1 prevalence,37 the method used for HIV-1 diagnosis played a significant role in the numbers of infected persons detected.

In 2008, Odaibo et al.38 reported that 6 (1.2%) out of 500 antibody-negative blood donor samples had HIV-1 antigens and cDNA. This report is comparable with what was observed in this study in which 8 (1.2%) samples positive on HIVAg/Ab ELISA were undetectable on Antibody-based testing kits (see Figure 1). The case is really worsened for HIV-1 rapid POC used in this study in which 16 samples (2.4%) were undetectable. The average score of HIV Rapid POC sensitivity observed in this study is similar to what was observed by Mba et al.40, findings from the study showed that rapid antibody kits may not be very useful for predonation HIV diagnosis. The agreement and predictive values scores of the three EIA kits show that the ELISA-based kits relate better as compared with the rapid kit. The usefulness of intra- and interrelatedness of diagnostic assays for viral diseases, such as Herpesviruses and SARS-COV2, have been previously reported by Aldisi et al.,28 Nasrallah et al.,29 and Yassin et al., 2020.30 Furthermore, as previously reported,39 we observed very few females participating in blood donation in Nigeria. Factors such as religion, education, social, and the physiology of females have been listed as reasons for this anomaly in Africa. It is important to impart proper education to the female gender so as to reverse the trend of male gender dominance with respect to blood donation in Africa.

It is important that blood donation testing centers use HIV antigen and antibody-based ELISA tests for pre-donation screening at the minimum. Other authors have shown the cost benefits of using only HIV antigen and antibody-based ELISA test kits for predonation blood screening rather than the two-step algorithm involving the use of HIV Rapid antibody kits.20 Findings from this study suggest that missed opportunities for HIV-1 diagnosis still occur even after the presence of detectable antibodies in blood samples if HIV rapid antibody kits are used. This missed diagnosis leads to further transmission of the virus to susceptible individuals. Although we could not associate specific sensitivities scores with HIV-1 screening methods against the various subtypes identified in this study, we have shown that antibody kits may not be very effective in detecting HIV-1 antibodies in areas where multiple HIV-1 subtypes circulate. It is inadvisable to use HIV-1 Rapid antibody kits for predonation screening in regions with diverse circulating HIV-1 subtypes, as studies have shown that HIV genetic diversity impacts diagnosis.40

Results of this study show that CRF02-AG and subtypes A and G in that order still remain the predominant circulating HIV-1 subtypes in Oyo state as well as among high-risk groups in the state. These strains have been shown to be circulating in the region since 1995.24,41 We have previously reported the detection of CRF02_AG, subtype K, recombinant strain GD, and an unassigned subtype among persons referred for malaria parasite testing (KY786266-272).16 In this study, more CRF02_AG and subtypes A and G were identified among febrile persons and blood donors.

As earlier stated, CRF02_AG remains the predominant subtype among high-risk groups in Oyo State. The strain is the predominant circulating virus in West Africa.7,24,41–43 Although CRF02_AG was first described in Ibadan, Nigeria, the origin of the virus is still not known, especially now that the strain is prevalent in several regions of the world. Subtypes A and G have also been previously reported as circulating in Oyo state as well as in other parts of Nigeria. A recent study identified CRF02_AG and subtypes G and A as the predominant circulating HIV-1 strains in Ibadan, Nigeria.7 These subtypes have also been detected in countries where subtype B predominates.44

It is important that an in-depth analysis of HIV-1 viral diversities in geographical regions is carried out. This is because subtype differences have been associated with varying patterns of replicative capacities, diagnosis, transmission, and pathogenesis. In another study, we have shown that HIV-1 strains circulating in Oyo State are associated with renal dysfunctions and reduced proportions of T cells in infected individuals during early stages of HIV-1 infection.45 Findings in this study observed more subtypes in Ibadan metropolis (urban settlement) as compared with Saki town (rural settlement). Recent studies using phylodynamic tools have suggested that HIV-1 strains originate and expand in urban areas before migrating to smaller rural centers.7 There is a need to describe the phylodynamics of HIV-1 subtypes in other states of the country, as this will shed further light on the diversity of the virus.

5 |. CONCLUSION

In summary, we have shown that the genetic diversity of HIV-1 strains among infected individuals in Oyo State, Nigeria, is still relatively high. This diversity is likely impacting diagnosis. Our study also suggests that screening persons for early HIV-1 infection is best carried out using antigen/antibody-based ELISA techniques for elimination of seroconversion. Early HIV-1-infected individuals are the major drivers of new infections. Hence, there is a need to use highly sensitive diagnostic tools for HIV-1 identection. This is particularly important for high-risk groups such as voluntary blood donors and febrile persons. Studies examining the impact of host immune pressures on the generation of HIV-1 immune escape mutants during the early stages of infection are ongoing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all individuals who participated in this study. They especially thank Mrs. Fadimu and Mrs. Adeyefa (both of Blood bank, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria) for their support in enrolling volunteer blood donors.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This study was supported by the University of Ibadan MEPI Junior Faculty Research Training Program (UI-MEPI-J) mentored research award through National Institute of Health (NIH) USA grant funded by Fogarty International Centre, the office of AIDS Research and National Human Genome Research Institute of NIH, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator under award number D43TW010140 to OD. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, assigned accession numbers MN943617-635.

Footnotes

SEQUENCE NOTES

All consensus nucleotide sequences obtained in this study were submitted to GenBank database and assigned accession numbers MN943617-635.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jmv.26872

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are openly available in a public repository that does not issue DOIs. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank, reference number MN943617-635.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2019 fact sheet | UNAIDS [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lima VD, St-Jean M, Rozada I, et al. Progress towards the United Nations 90-90-90 and 95-95-95 targets: The experience in British Columbia, Canada. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2017;20(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. New Fast Track Strategy to end AIDS by 2030. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peeters M, Toure-Kane C, Nkengasong JN. Genetic diversity of HIV in Africa: impact on diagnosis, treatment, vaccine development and trials. AIDS. 2003;17(May):2547–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeters M. The genetic variability of HIV-1 and its implications. Transfus Clin Biol. 2001;8:222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeters M, Jung M, Ayouba A. The origin and molecular epidemiology of HIV. Expert Rev. 2013;11(9):885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nazziwa J, Faria NR, Chaplin B, et al. characterisation of HIV-1 molecular epidemiology in Nigeria: origin, diversity, demography and geographic spread. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020;10(1):3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fayemiwo SA, Odaibo GN, Oni AA, Ajayi AA, Bakare RA, Olaleye DO. Genital ulcer diseases among HIV-infected female commercial sex workers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci [Internet]. 2011;40(1): 39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyefara JL. Food insecurity, HIV/AIDS pandemic and sexual behaviour of female commercial sex workers in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. SAHARA J. 2007;4(2):626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osaro E, Mohammed N, Zama I, et al. revalence of p24 antigen among a cohort of HIV antibody negative blood donors in Sokoto, north western Nigeria - The question of safety of blood transfusion in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odaibo GN, Adewole IF, Olaleye DO. High Rate of non-detectable HIV-1 RNA among antiretroviral drug naive HIV positive individuals in Nigeria. Virol Res Treat [Internet]. 2013;4:VRT.S12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atilola GO, Akpa OM, Komolafe IOO. HIV/AIDS and the longdistance truck drivers in south-west Nigeria: A cross-sectional survey on the knowledge, attitude, risk behaviour and beliefs of truckers. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3(4):166–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azuonwu O, Erhabor O, Frank-Peterside N. HIV infection in longdistance truck drivers in a low income setting in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. J Community Health, 36(4):583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ijeoma A, Ejikeme A, Theodora O, Chika O. Knowledge, attitude, willingness of HIV counseling and testing and factors associated with it, among long distant drivers in Enugu, Nigeria: an opportunity in reduction of HIV prevalence. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18:1088–1097.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Njoku OS, Manak MM, O’Connell RJ, et al. An evaluation of selected populations for HIV-1 vaccine cohort development in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olusola BA, Olaleye DO, Odaibo GN. Early HIV infection among persons referred for malaria parasite testing in Nigeria. Arch Virol. 2017;163(2):439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders EJ, Mugo P, Prins HAB, et al. Acute HIV-1 infection is as common as malaria in young febrile adults seeking care in coastal Kenya. AIDS. 2014;28(9):1357–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders EJ, Wahome E, Powers KA, et al. Targeted screening of atrisk adults for acute HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS J. 2016;29(0 3):1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awan SA, Junaid A, Sheikh S. Transfusion transmissible infections: maximizing donor surveillance. Cureus. 2018;10(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shittu AO, Olawumi HO, Adewuyi JO. Pre-donation screening of blood for transfusion transmissible infections: the gains and the pains - experience at a resource limited blood bank. Ghana Med J. 2014;48(3):158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olowe OA, Mabayoje VO, Akanbi O, et al. HIV P24 antigen among HIV antibody seronegative blood donors in Osogbo Osun State, South Western Nigeria. Pathog Glob Health [Internet]. 2016; 110(4–5):205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Japhet M, Adewumi O, Adesina O, Donbraye E. High prevalence of HIV p24 antigen among HIV antibody negative prospective blood donors in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. J Immunoass Immunochem. 2016;37: 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott T, Sanders EJ, Doherty M, et al. Challenges of HIV diagnosis and management in the context of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), test and start and acute HIV infection: a scoping review [Internet]. Journal of the International AIDS Society. John Wiley and Sons Inc. 2019;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sankalé JL, Langevin S, Odaibo G, et al. The complexity of circulating HIV type 1 strains in Oyo state. Nigeria. 2007;23(8):1020–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gall A, Ferns B, Morris C, et al. Universal amplification, next-generation sequencing, and assembly of HIV-1 genomes. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(12):3838–3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidal N, Peeters M, Mulanga-Kabeya C, et al. Unprecedented degree of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M genetic diversity in the democratic republic of Congo suggests that the HIV-1 pandemic originated in Central Africa. J Virol. 2000;74(22): 10498–10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gourraud PA, Karaouni A, Woo JM, et al. APOBEC3H haplotypes and HIV-1 pro-viral vif DNA sequence diversity in early untreated HIV-1 infection. Hum Immunol. 2011;72(3):207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yassine HM, Al-Jighefee H, Al-Sadeq DW, et al. performance evaluation of five ELISA kits for detecting anti-SARS-COV-2 IgG antibodies. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldisi RS, Elsidiq MS, Dargham SR, et al. performance evaluation of four type-specific commercial assays for detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 antibodies in a Middle East and North Africa population. J Clin Virol. 2018;103:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasrallah GK, Dargham SR, Sahara AS, Elsidiq MS, Abu-Raddad LJ. performance of four diagnostic assays for detecting herpes simplex virus type 2 antibodies in the Middle East and North Africa. J Clin Virol. 2019;111:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charurat M, Nasidi A, Delaney K, et al. characterization of acute HIV-1 infection in high-risk Nigerian populations. J Infect Dis. 2012; 205(8):1239–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bebell LM, Pilcher CD, Dorsey G, et al. cute HIV-1 infection is highly prevalent in Ugandan adults with suspected malaria. AIDS J. 2011; 24(12):1945–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charurat M, Nasidi A, Delaney K, et al. characterization of acute HIV-1 Infection in high-risk Nigerian populations. J Infect Dis. 2012; 205:1239–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Mpendo J, et al. High HIV-1 prevalence, risk behaviours, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisinger R, Dieffenbach C, Fauci A. HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection undetectable equals untransmittable. JAMA [Internet]. 2019;321(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okoroiwu HU, Okafor IM, Asemota EA, Okpokam DC. Seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections (HBV, HCV, syphilis and HIV) among prospective blood donors in a tertiary health care facility in Calabar, Nigeria; an eleven years evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNAIDS. Nigeria | UNAIDS [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2020 Mar 1]. Available from https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odaibo GN, Taiwo A, Aken’Ova YA, Olaleye DO. Detection of HIV antigen and cDNA among antibody-negative blood samples in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2008;102(3): 284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erhabor O, Isaac Z, Abdulrahaman Y, et al. Female gender participation in the blood donation process in resource poor settings: case study of Sokoto in North Western Nigeria. J Blood Disord Transfus. 2014;05(01). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eko Mba JM, Bisseye C, Mombo LE, et al. Assessment of rapid diagnostic tests and fourth-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the screening of human immunodeficiency and hepatitis B virus infections among first-time blood donors in Libreville (Gabon). J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33(3):e22824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olaleye DO, Sheng Z, Howard TM, Rasheed S. Isolation and characterization of a new subtype A variant of human immunodeficiency virus type I from Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1(1):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mboudjeka I, Zekeng L, Takehisa J, et al. HIV type 1 genetic variability in the northern part of Cameroon. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15(11):951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ragupathy V, Zhao J, Wood O, et al. Identification of new, emerging HIV-1 unique recombinant forms and drug resistant viruses circulating in Cameroon. Virol J. 2011;8:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siemieniuk RA, Beckthold B, Gill MJ. Increasing HIV subtype diversity and its clinical implications in a sentinel North American population. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2013;24(2):69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olusola BA, Kabelitz D, Olaleye DO, Odaibo GN. Early HIV infection is associated with reduced proportions of gamma delta T subsets as well as high creatinine and urea levels. Scand J Immunol. 2020:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]