Abstract

Purpose:

Studies have examined trends in cannabis vaping, but research is needed to examine trends in more frequent use as this may increase risk for adverse health outcomes.

Methods:

Data were from 12,561 high school seniors participating in the Monitoring the Future national study. Prevalence of self-reported frequent vaping of cannabis (defined as using ≥10 times in the past month) was compared between 2018 and 2019 cohorts.

Results:

Frequent vaping of cannabis significantly increased from 2.1% to 4.9%, a 131.4% increase. This increase was larger than the increase for any vaping of cannabis (which increased 85.9%). Notable significant increases occurred among students ages ≥18 (a 154.9% increase), female students (a 183.5% increase), those who go out 4–7 evenings per week (a 163.0% increase), and those reporting past-year nonmedical prescription opioid use (a 184.7% increase).

Conclusions:

Frequent vaping of cannabis is increasing among adolescents in the US, particularly among select subgroups.

Keywords: cannabis, vaping, drug use

Introduction

Despite rapidly shifting state-level cannabis policy in the US, prevalence of cannabis use among adolescents has remained relatively stable [1]. However, daily use is increasing among some age groups [2], modes of administration have been shifting [2], and past-month vaping of cannabis among high school seniors increased from 5.0% to 14.0% from 2017 through 2019 [1]. While largescale national studies suggest that prevalence of cannabis vaping has increased among adolescents, research is needed to examine trends in higher-frequency use which may increase risk for adverse health outcomes.

It is currently unknown whether vaping of nicotine or cannabis products is definitively safer than smoking combustible products [3], but some cannabis vaping behaviors appear to place users at increased risk for electronic-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI). As of February 18, 2020, there was a total of 2,807 cases of EVALI in the US, including 68 deaths [4,5]. Alarmingly, among these cases, 82% reported vaping products containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)—the main psychoactive component in cannabis [4]. Such patients diagnosed with EVALI have not only been shown to be more likely to exclusively vape THC products, but they are also more likely to vape such products more than five times per day and to use counterfeit or black market THC-containing products [6]. While Vitamin E acetate present in various products may be the main causative factor for EVALI [4,5], frequent vaping of cannabis products is a risk factor.

Although research is lacking regarding risks associated with frequent vaping of cannabis, frequent cannabis use is associated with higher risk for cannabis use disorder [7] and for higher risk of use of other drugs such as cocaine, LSD, other hallucinogens, and nonmedical use of prescription opioids, amphetamine, and tranquilizers [8]. Further research is needed to determine how use of these drugs relate to cannabis vaping. Further, research is needed to examine trends in more frequent vaping of cannabis.

Methods

Design

Monitoring the Future (MTF) is a nationally representative survey of high school students in the US [1]. A cross-section is surveyed every year in public and private schools throughout 48 states using a multi-stage random sampling procedure. In 2018 and 2019, students were surveyed at 256 schools (128 schools each year), and student response rates were 81% and 80%, respectively [1]. MTF was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board (IRB) and the New York University Langone Medical Center IRB deemed this secondary analysis exempt from review.

Participants

MTF randomly distributes six different survey forms throughout schools. In 2018, cannabis vaping was queried on two forms and in 2019 it was queried on four forms. Therefore, this analysis focuses on 4,072 high school seniors in 2018 and 8,314 in 2019, which is a total of 12,561 students providing data on use.

Measures

Students were asked their age, sex, race/ethnicity, and about the highest level of education attained by their parent(s). They were also asked how many evenings they go out per week for fun or recreation. With respect to drug use, students were asked how many days they vaped cannabis in the past 30 days with responses ranging from 0 to ≥20 days [1]. Responses were recoded into binary variables indicating any past-month use (use at least once in the past month) and frequent use defined as using ≥10 times in the past month [9]. Students were also asked about past-year vaping of nicotine, past-year use of alcohol, cannabis, LSD, psychedelics other than LSD, and cocaine, and past-year nonmedical use of amphetamine, prescription opioids, and tranquilizers. Nonmedical use was defined as using without a doctor’s orders. On one survey form, those reporting past-year cannabis use were asked if it was 1) smoked, 2) eaten, 3) drank, 4) dabbed (use of concentrate such as “wax” or “shatter”), or 5) used via another method.

Analysis

First, prevalence of past-month vaping and frequent vaping of cannabis was estimated and compared between 2018 and 2019. Next, comparisons with respect to frequent use were repeated, stratified by participant characteristics. These bivariable tests were conducted using Rao Scott chi-square and sample weights were used to account for the complex sample design [10].

Results

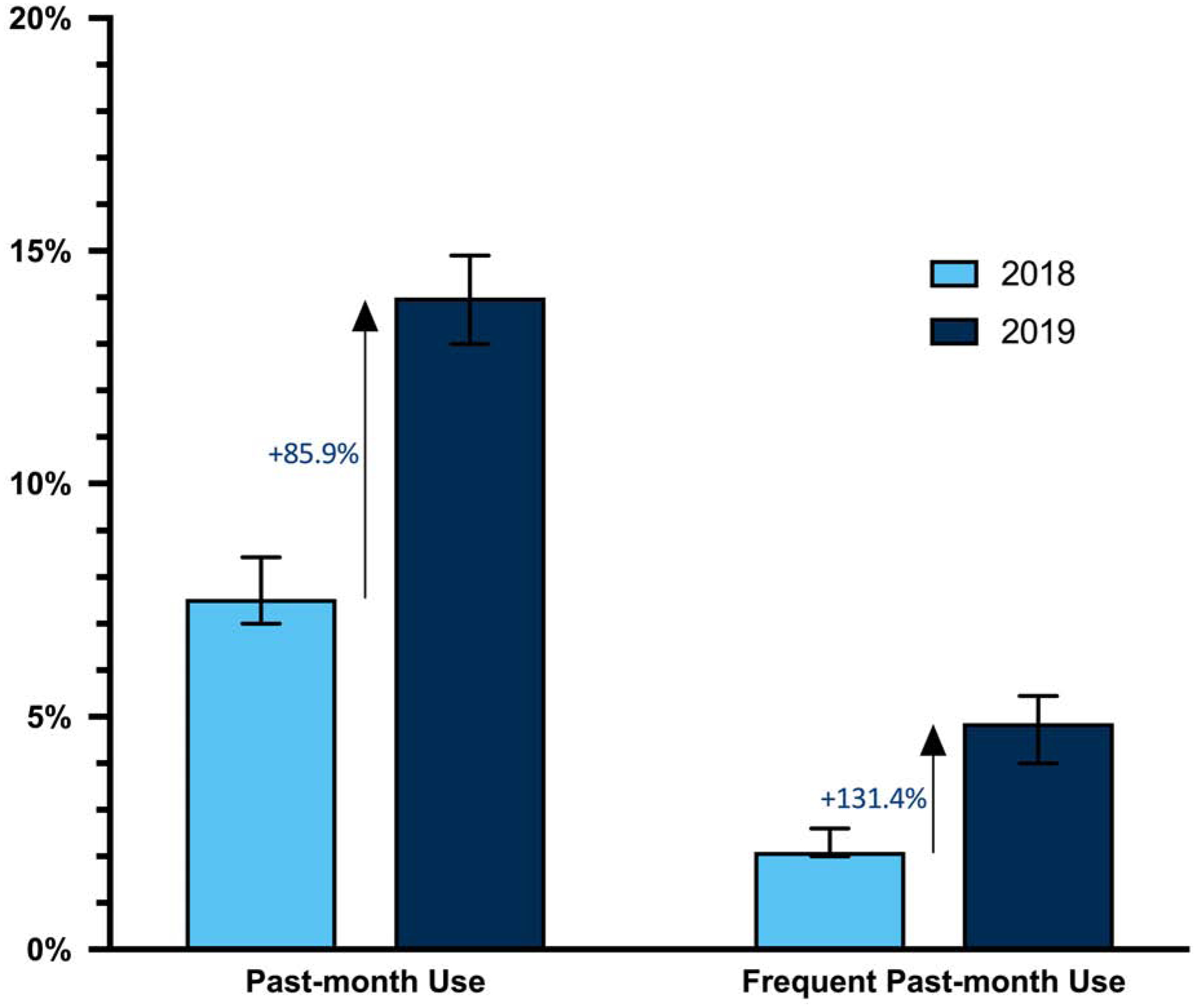

Between 2018 and 2019, past-month vaping of cannabis (among the full sample) increased from 7.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.7–2.6) to 14.0% (95% CI=13.1–14.9; p<.001), an 85.9% relative increase, and frequent use increased from 2.1% (95% CI=1.7–2.6) to 4.9% (95% CI=4.3–5.5; p<.001), a 131.4% relative increase (Figure 1). Across strata (Table 1), all subgroups significantly increased frequent use. Notable increases occurred among students ages ≥18 (a 154.9% increase; p<.001), female students (a 183.5% increase; p<.001), and among those who go out 4–7 times per week (a 163.0% increase; p<.001). Among students who have used other drugs in the past-year, absolute increases in prevalence of frequent vaping were most notable among those who used psychedelics other than LSD (a 21.0% absolute increase; p=.032), prescription opioids (nonmedical use; a 20.5% absolute increase; p<.001), tranquilizers (nonmedical use; a 19.4% absolute increase; p<.001), and/or cocaine (a 15.8% absolute increase; p=.026).

Figure 1.

Changes in Any Past-Month Vaping of Cannabis and Frequent Vaping of Cannabis between 2018 and 2019

Table 1.

Changes in Estimated Past-Month Frequent Vaping of Cannabis among High School Seniors Stratified by Participant Characteristics, 2018–19

| 2018 Weighted % (95% CI) | 2019 Weighted % (95% CI) | % Absolute Change 2018–19 | % Relative Change 2018–19 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <18 | 2.2 (1.6–3.0) | 4.6 (3.8–5.5) | 2.4 | 106.3 | <.001 |

| ≥18 | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 4.9 (4.2–5.7) | 3.0 | 154.9 | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.9 (2.2–3.9) | 6.0 (5.2–7.0) | 3.1 | 105.5 | <.001 |

| Female | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 3.6 (3.0–4.4) | 2.3 | 183.5 | <.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 2.2 (1.6–2.9) | 4.5 (3.9–5.3) | 2.4 | 110.2 | <.001 |

| Nonwhite | 2.0 (1.3–3.1) | 4.1 (3.2–5.1) | 2.0 | 101.0 | .004 |

| Parent Education | |||||

| High School or Less | 2.2 (1.4–3.3) | 5.0 (4.0–6.1) | 2.8 | 129.5 | <.001 |

| Some College | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | 4.8 (3.7–6.2) | 2.7 | 125.5 | .007 |

| College Degree | 2.3 (1.7–3.1) | 4.3 (3.6–5.2) | 2.0 | 88.2 | <.001 |

| Evenings Out Per Week | |||||

| 0–3 Evenings | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 3.6 (3.1–4.1) | 1.9 | 113.2 | <.001 |

| 4–7 Evenings | 4.6 (3.0–7.0) | 12.1 (9.9–14.6) | 7.5 | 163.0 | <.001 |

| Past-Year Drug Use | |||||

| Alcohol | 3.5 (2.8–4.4) | 8.2 (7.2–9.2) | 4.6 | 130.9 | <.001 |

| Vaped Nicotine | 5.7 (4.5–7.2) | 11.8 (10.4–13.2) | 6.1 | 107.7 | <.001 |

| Prescription Opioids | 11.1 (6.7–17.8) | 31.6 (24.8–39.4) | 20.5 | 184.7 | <.001 |

| Amphetamine | 12.9 (8.5–18.9) | 27.3 (22.1–33.3) | 14.4 | 111.6 | <.001 |

| Tranquilizers | 14.3 (8.7–22.5) | 33.7 (26.9–41.3) | 19.4 | 135.7 | <.001 |

| LSD | 21.7 (14.7–30.8) | 34.2 (27.1–42.1) | 12.5 | 57.6 | .032 |

| Other Psychedelics | 20.2 (12.6–30.8) | 41.2 (32.7–50.3) | 21.0 | 104.0 | .003 |

| Cocaine | 20.4 (12.5–31.4) | 36.2 (27.5–45.8) | 15.8 | 77.5 | .026 |

| Past-Year Cannabis Use | |||||

| Any Form | 5.9 (4.7–7.3) | 13.4 (12.0–15.0) | 7.5 | 127.1 | <.001 |

| Smoked | 5.8 (4.1–8.2) | 12.2 (9.4–15.7) | 6.4 | 110.3 | <.001 |

| Consumed in Food | 10.0 (6.8–14.4) | 18.8 (14.1–24.6) | 8.8 | 88.0 | .007 |

| Drank | 41.8 (24.0–62.1) | 51.5 (30.2–72.2) | 9.7 | 23.2 | .530 |

| Dabbed | 15.2 (10.6–21.3) | 23.4 (17.5–30.6) | 8.2 | 53.9 | .054 |

| Other | 15.4 (7.4–29.4) | 31.1 (17.8–48.5) | 15.7 | 101.9 | .103 |

Frequent vaping is defined as vaping ≥10 times in the past month. Specific forms of cannabis use (i.e., smoking, eating, drinking, dabbing, other) were only queried on Form 1, so data were only collected from a quarter of the analytic sample. Dabbing referred to using a concentrate such as “wax”, “honey oil”, “budder”, or “shatter”. Race/ethnicity responses for those not identifying as White, Black, or Hispanic were not available in the public dataset. Black and Hispanic were collapsed to account for too few Black students reporting use in 2018. Parent education refers to the highest level of education reportedly completed (according to student) of any parent. Evenings out per week refers to number of times participants go out for fun or recreation. Prescription opioids (“narcotics other than heroin”), amphetamine, and tranquilizers refer to nonmedical use, defined as participants using on their own without a doctor telling them to take them. Missing data were excluded during stratification and missingness was as follows: frequent vaping of cannabis (10.2%), age (6.7%), sex (10.3%), race/ethnicity (22.5%), parent education (12.0%), evenings out (11.7%), alcohol (7.2%), vaped nicotine (9.9%), opioids (7.7%), amphetamine (6.3%), tranquilizers (7.4%), LSD (5.9%), other psychedelics (6.3%), cocaine (8.0%), any cannabis (6.5%), smoked cannabis (5.3%), consumed cannabis (5.3%), liquid cannabis (5.3%), dabber cannabis (5.3%), and other cannabis method (5.3%). P-values refer to differences between 2018 and 2019 computed via Rao Scott chi-square. CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Frequent vaping of cannabis more than doubled among high school seniors in the US between 2018 and 2019. Cannabis vaping is indeed increasing, but frequent vaping of cannabis is increasing at a higher rate. Frequent vaping increased across demographic subgroups but increases tended to be particularly prominent among older and female students and among those who used other drugs in the past year. Those who used psychedelics or engaged in nonmedical use of prescription opioids in particular vaped more frequently across time.

More research is needed to determine the extent to which vaping of cannabis increases risk for initiating other drugs or whether this form of use is merely being added to existent drug repertoires. Research is also needed to determine the extent to which high-frequency vaping of cannabis increases risk for cannabis use disorder.

A limitation of this study is that adolescents chronically absent or who dropped out are underrepresented. More frequent or heavy vaping (monthly use ≥20 times) and past-month use of other drugs could not be examined because sample sizes for some subgroups were too small. Impaired recall can also influence self-report of use, and under- or over-reporting of use of other drugs could have affected estimates.

Continued research into frequent vaping of cannabis is needed as this may place adolescents who use at higher risk for EVALI, cannabis use disorder, and other drug use.

Implications and Contribution.

Studies have examined trends in cannabis vaping, but research was needed to examine trends in frequent use as this may increase risk for adverse health outcomes. This study found that frequent vaping of cannabis is increasing at a faster rate than any vaping of cannabis among high school seniors.

Acknowledgement:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA044207 (PI: Palamar). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The author would like to thank the principal investigators (PIs: Miech, Johnston, Bachman, O’Malley, and Schulenberg) at The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center, and the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research for providing public access to these data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knapp AA, Lee DC, Borodovsky JT, et al. Emerging trends in cannabis administration among adolescent cannabis users. J Adolesc Health 2019;64:487–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotts JE, Sven-Eric J, McConnell R, Tarran R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ 2019;366:l5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Retrieved January 26, 2021 from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- 5.Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: Characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury - United States, August 2019-January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products - Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung J, Chan GCK, Hides L, Hall WD. What is the prevalence and risk of cannabis use disorders among people who use cannabis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Behav 2020;109:106479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palamar JJ, Griffin-Tomas M, Kamboukos D. Reasons for recent marijuana use in relation to use of other illicit drugs among high school seniors in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2015;41:323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick ME, Berglund PA, Joshi S, Bray BC. A latent class analysis of heavy substance use in Young adulthood and impacts on physical, cognitive, and mental health outcomes in middle age. Drug Alcohol Depend 2020;212:108018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied Survey Data Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]