Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a devastating consequence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection.1,2 Prior single-center studies have reported ICH in patients with COVID-19, but these findings have not been confirmed in a multicenter study.3,4

We sought to describe the prevalence of ICH among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease registry and compare the clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with and without ICH.

Methods

Data are available from the American Heart Association after approval of a research proposal (www.heart.org/qualityresearch). We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of patients enrolled in the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease registry.5 This registry includes consecutive patients ≥18 years old hospitalized with COVID-19 from March 2020 to December 2020 at 107 US hospitals. Patients were enrolled without consent through the Common Rule or through an institutional review board authorization/exemption waiver. Presence of ICH was recorded on the registry case report form. Mortality was defined as either in-hospital death or discharge to hospice. We report descriptive statistics of those with and without ICH. Statistical comparisons were not performed due to the small number of patients with ICH.

Results

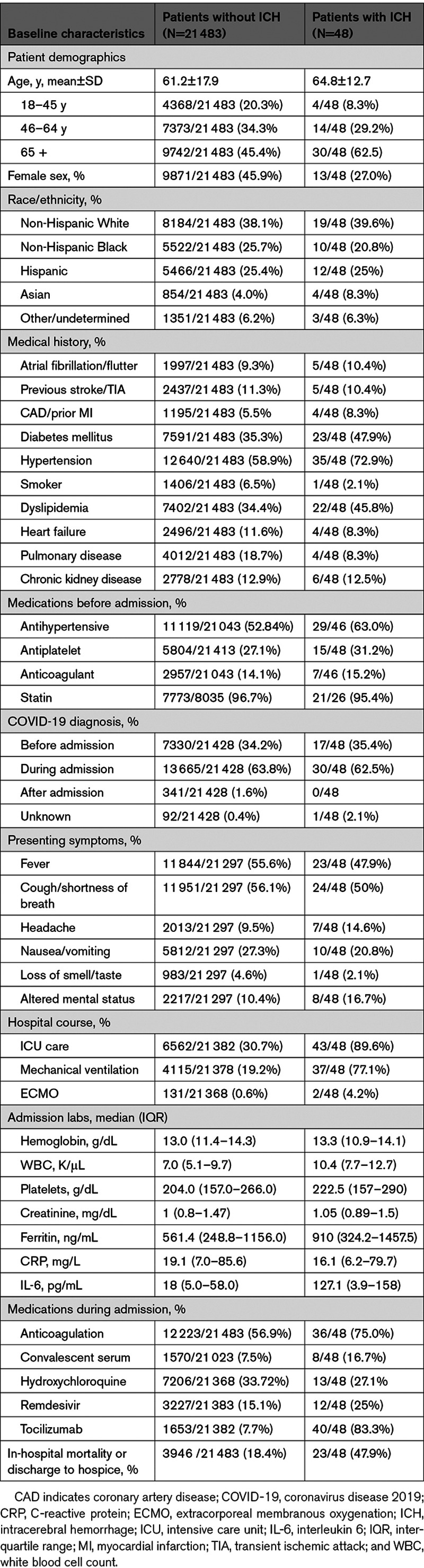

This release of the COVID-19 registry included 21 483 patients, of which 48 (0.2%) had an ICH. COVID-19 was diagnosed before ICH in 26 patients, on the same day as ICH in 10 patients, and during hospitalization for ICH in 6 patients. Compared with patients without ICH, those with ICH were nominally older (65 versus 61 years), predominantly male (73% versus 54%), and had more vascular risk factors (Table).

Table.

Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 Positive Patients With and Without ICH

During hospitalization, 75% of patients with ICH received anticoagulation compared with 57% of patients without ICH. Patients with ICH had higher levels of inflammatory markers at admission; were more likely to require intensive care (90% versus 30%), mechanical ventilation (77% versus 19%), and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation (4% versus 0.6%); and had a higher mortality (48% versus 18%) than those without ICH (Table). Of the patients with ICH who died, 15 were diagnosed with COVID-19 before ICH.

Discussion

We report characteristics of ICH in over 21 000 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 from the American Heart Association COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease registry. We found that ICH was rare among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and that patients with ICH had higher mortality than those without ICH. We also observed greater use of anticoagulation in patients with versus without ICH, supporting the findings of early single-center studies of ICH in COVID-19 in the New York City health system.1,4

Although this is the first multicenter study of ICH in COVID-19, there are limitations. First, we describe the prevalence of ICH only among patients hospitalized with COVID-19; prevalence may differ among patients who did not seek or require hospital-based care for COVID-19. Second, reporting hospitals may not be representative of all US hospitals. Third, we lacked detailed data on the timing of ICH relative to hospital admission, COVID-19 diagnosis, and anticoagulation and lacked a control group for comparison. We are, therefore, unable to make causal assumptions about COVID-19 and ICH. Fourth, we lacked data on the location and severity of ICH. Fifth, the small number of patients with ICH precluded statistical analyses. ICH may have been under-ascertained in the registry, as many patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may not have had neuroimaging to detect an ICH.

In summary, our findings suggest that ICH is rare among patients hospitalized for COVID-19. While mortality in ICH is typically high, it may be higher than expected in ICH patients with COVID-19. Further studies are needed to determine the risk, predictors, and outcomes of ICH during COVID-19, particularly among patients who are treated with anticoagulation.

Acknowledgments

The Get With The Guidelines programs are provided by the American Heart Association. The American Heart Association Precision Medicine Platform (https://precision.heart.org/) was used for data analysis. IQVIA (Parsippany, New Jersey) serves as the data collection and coordination center.

Sources of Funding

The American Heart Association (AHA)’s suite of Registries is funded by multiple industry sponsors. AHA COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) registry is partially supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. A.C. Leasure is supported by the AHA Medical Student Research Fellowship. Dr Falcone is supported by the Neurocritical Care Society. Drs Sansing and Sheth are supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Drs Elkind receives royalties from UpToDate for a chapter on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and neurological disease and serves as an unpaid officer of the American Heart Association. Dr Sansing reports grants from NINDS and grants from the American Heart Association during the conduct of the study; grants from NINDS and grants from American Heart Association outside the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts.

Footnotes

This manuscript was sent to Tanya Turan, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page e323.

Contributor Information

Audrey C. Leasure, Email: audrey.leasure@yale.edu.

Yosef M. Khan, Email: Yosef.khan@heart.org.

Raakhee Iyer, Email: raakhee92@gmail.com.

Mitchell S.V. Elkind, Email: mse13@columbia.edu.

Lauren H. Sansing, Email: lauren.sansing@yale.edu.

Guido J. Falcone, Email: guido.falcone@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Melmed KR, Cao M, Dogra S, Zhang R, Yaghi S, Lewis A, Jain R, Bilaloglu S, Chen J, Czeisler BM, et al. Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51:953–960. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02288-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1018–1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dogra S, Jain R, Cao M, Bilaloglu S, Zagzag D, Hochman S, Lewis A, Melmed K, Hochman K, Horwitz L, et al. Hemorrhagic stroke and anticoagulation in COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104984. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kvernland A, Kumar A, Yaghi S, Raz E, Frontera J, Lewis A, Czeisler B, Kahn DE, Zhou T, Ishida K, et al. Anticoagulation use and hemorrhagic stroke in SARS-CoV-2 patients treated at a new york healthcare system. Neurocrit Care. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01077-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alger Heather M, Rutan Christine, Williams Joseph H, Walchok Jason G, Bolles Michele, Hall Jennifer L, Bradley Steven M, Elkind Mitchell S.V, Rodriguez Fatima, Wang Tracy Y, et al. American heart association COVID-19 CVD registry powered by get with the guidelines. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2020;13:e006967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]