Abstract

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia has plant growth-promoting potential, and interaction with Arachis hypogaea changes host-plant physiology, biochemistry, and metabolomics, which provides tolerance under the N2 starvation conditions. About 226 suppression subtractive hybridization clones were obtained from plant-microbe interaction, of which, about 62% of gene sequences were uncharacterized, whereas 23% of sequences were involved in photosynthesis. An uncharacterized SSH clone, SM409 (full-length sequence showed resemblance with Cytb6), showed about 4-fold upregulation during the interaction was transformed to tobacco for functional validation. Overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene enhanced the seed germination efficiency and plant growth under N2 deficit and salt stress conditions compared to wild-type and vector control plants. Results confirmed that transgenic lines maintained high photosynthesis and protected plants from reactive oxygen species buildup during stress conditions. Microarray-based whole-transcript expression of host plants showed that out of 272,410 genes, 8704 and 24,409 genes were significantly (p < 0.05) differentially expressed (> 2 up or down-regulated) under N2 starvation and salt stress conditions, respectively. The differentially expressed genes belonged to different regulatory pathways. Overall, results suggested that overexpression of AhCytb6 regulates the expression of various genes to enhance plant growth under N2 deficit and abiotic stress conditions by modulating plant physiology.

Subject terms: Molecular engineering in plants, Abiotic

Introduction

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) improve plant growth and development directly and/or indirectly: directly by nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, siderophore, and phytohormone production and indirectly by acting as a biocontrol agent or by activating induced systemic resistance (ISR) in the host plant1,2. Interaction of PGPR or pathogenic bacteria with the host plants causes various signalings, which leads to the activation of the host immune system. However, plants differentiate between PGPR and pathogenic bacteria based on response times, activation of genes, and their expression levels3,4. Utilization of the potential of the PGPR and their effect on the host transcriptional machinery is a great avenue for the development of sustainable agriculture for biotic and abiotic stress-affected crop plants.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change5, changes in climatic conditions and agricultural habits, and increased use of chemical fertilizers cause various abiotic stresses in legumes, which affect their growth and productivity. Abiotic stresses in soil (salt, cold, drought, waterlogging, metal toxicity, pH, and low availability of nutrients, among others) cause an alteration in the microbial flora of soil, which affects the symbiotic relationship between legumes and rhizobia6,7. Nitrogen is a major nutrient element for plant growth and development due to its central role and presence in many biomolecules like protein, chlorophyll, and nucleic acid8. Nitrogen also acts as a regulator for the carbon cycle, which directly affects the photosynthetic machinery of plants9. It is well established that nutrient homeostasis plays a key role in plant growth and development. Nutrient deficiency, including the N2 starvation condition, leads to stress conditions and activates the nutrient-deprivation signal transduction. In nitrogen starvation conditions, plants use their stored nitrogen, and more than half of the leaf nitrogen is used in photosynthetic machinery, thus plants have to compromise with growth (less nitrogen for structural proteins) and yield (early senescence)10. Differential expression of key genes coordinates with plant physiology to manage the demand for nutrients. The low availability of nitrogen in the soil decreases the yield of the crop, which could be compensated for by the application of N2 fixing bacteria11. In this scenario, we need diazotrophic bacteria that are tolerant to abiotic stress and act as PGPR to balance the nutrient cycle between the plant-microbe-soil dynamic in stress conditions. The use of PGPR for the enhancement of crop productivity under various biotic and abiotic stresses is better for sustainable and environmentally friendly agriculture12.

There are a plethora of studies that show the improvement in yield and health of plants after application of PGPR13–16, and some studies showed changes at the molecular level (transcript expression) in the host plant after interaction with PGPR17. There is a need to understand the changes and events taking place at the molecular level in the host plant after interaction with PGPR under abiotic stress, and utilizing the differentially expressed gene for the potential candidate for the bioengineering of the host genome could be a highly translational strategy.

In nature, the peanut plant is associated with various nitrogen-fixing, nodulating rhizobacteria, which help in nitrogen fixation. However, the lack of specificity of this interaction make it difficult to understand the specific changes that occur at the molecular level during the interaction. To understand the effect of a specific single PGPR on plant growth promotion and molecular changes in A. hypogaea, we used the strain Stenotrophomonas maltophilia BJ01, isolated from non-crop and non-leguminous plants from the coastal saline area18. We reported the effect of single PGPR S. maltophilia BJ01 on the physio-biochemical and metabolic changes on the host plant under nitrogen starvation and salt stress conditions19,20. Differential expression of genes due to plant-PGPR interaction will provide the molecular mechanism of PGPR-action as well as useful insight about the potential gene candidates to be explored for sustainable agriculture under stress conditions.

In this study, we found that the AhCytb6 gene is differentially expressed in peanut under nitrogen-starved conditions after interaction with S. maltophilia BJ01. To understand the role of this gene in the host plant, we engineered the genome of the model plant (tobacco) and inserted AhCytb6 along with the expression cassette in the genome. Ectopic overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene in transgenic tobacco enhances plant performances under nitrogen starvation and salt stress. The role of AhCytb6 was also explored for the growth and development of plants and their stress responses. Cytb6 is a key regulatory unit of the electron transport chain in plants and affects the photosynthetic efficiency and yield of plants21,22. Recently, Lande et al. reported that abiotic stress drastically decreases the proteins related to Cytb6 in chickpea23. Overexpression of this gene increases the photosynthetic ability, biomass and yield of the plants under various abiotic stresses24–26. Our results showed that the photosynthesis gene AhCytb6 is differentially expressed in host plants due to interaction with PGPR, and overexpression of this gene provides tolerance to the model plants under N2 starvation and abiotic stress conditions.

Results

Differential expression of genes in the response of S. maltophilia BJ01 under N2 starvation condition

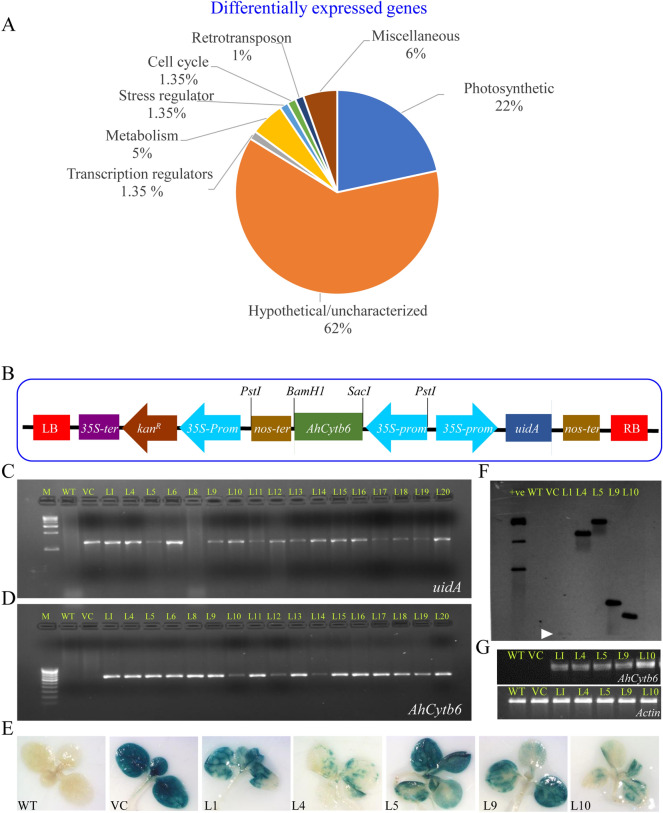

There were 400 SSH (suppression subtractive hybridization) clones sequenced and subjected to chimera analysis, and 226 resultant clone sequences were obtained, which were subjected to BLAST and categorized into eight-groups (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, about 62% of differentially expressed gene sequences did not show significant similarity with known genes and were categorized as unknown/uncharacterized/hypothetical. Similarly, 23% of EST sequences were involved in photosynthesis. About 3% of sequences belonged to apoptosis, while 1% EST were signaling molecules, transcription factors, stress regulators, and metabolism. About 3% of sequences did not show any resemblance and fell under the miscellaneous category. Transcript profiling of representative genes from selected categories showed differential up-regulation in PGPR-treated peanut plants (Fig. S1). Based on transcript expression profiling, clone SM409 showed 4.1-fold upregulation and resemblance with uncharacterized/ hypothetical protein and was selected for further study. The full-length SM409 clone (ORF) sequence showed resemblance (99.69% sequence similarity with 100% query coverage) to the chloroplast genome (CDS: cytochrome b6) of Arachis spp., especially different cultivars of Arachis hypogaea (accession no. CP030984; MG814006–9; NC_037358; KX257487; KJ468094); therefore, the cloned gene was named AhCytb6. Moreover, the deduced protein (amino acid) sequence showed 93.72% similarity (with 97% query coverage) with the cytochrome b6 protein of Arachis hypogaea (accession no. YP_009472186) in the homology search.

Figure 1.

Differential expression of genes analyzed by suppression subtractive hybridization and genetic transformation and molecular confirmation of transgenic lines. (A) Genes were differentially expressed in Arachis hypogaea treated with plant growth promoting S. maltophilia BJ01 plant under N2 starvation condition (B) Schematic representation of AhCytb6 gene-pCAMBIA2301 plant transformation vector construct, PCR amplification of (C) uidA and (D) AhCytb6 genes, (E) Histochemical GUS assay of selected transgenic lines, (F) Southern blot and (G) Reverse transcriptase PCR analysis.

Cloning and in silico analysis of the AhCytb6 gene

The AhCytb6 gene was 1287 base pair long (accession no. MT395343) and was comprised of 34 bp 5′-untranslated leader sequences (5′-UTR), 636 bp of an open reading frame (ORF) and 617 bp of a 3′-UTR (5′-UTR: 1–34 bp, ORF: 35–670 bp and 3′-UTR: 671–1287 bp) (Fig. S2). In genome organization study, the amplification of 636 bp AhCytb6 gene ORF was obtained from both genomic and cDNA, which revealed that the gene is intronless (Fig. S3). The ORF encodes for 211 amino acids having a molecular mass of 23.59 kD. In silico analysis revealed that the PI of the deduced protein was 10.6 and the instability index was 32.98; the protein half-life was predicted 30 h in mammalian reticulocytes (in vitro), more than 20 h in yeast (in vivo), and more than 10 h in Escherichia coli (in vivo), which showed that the protein was stable in nature. The in silico analysis predicted that the AhCytb6 peptide contained four transmembrane domains and was in the plasma membrane (Fig. S4).

Genetic transformation and molecular confirmation of transgenic lines

About 25 putative transgenic lines (T0) were obtained after tissue culture, out of which 17 lines showed seed germination on kanamycin, which carried forward further for the generation of T1 transgenic lines. Integration transgenes were confirmed in all 17-transgenic lines by amplification of 1.2 kb of the uidA gene and 636 bp of the AhCytb6 gene (Fig. 1B–D and Fig. S5). All plants were found positive, and based on histochemical gus expression, five lines (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) were selected (Fig. 1E). Selected transgenic lines showed single gene integration and high expression of the AhCytb6 gene analyzed by southern blot and semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis, respectively, in all selected lines (Fig. 1F, G and Fig. S5).

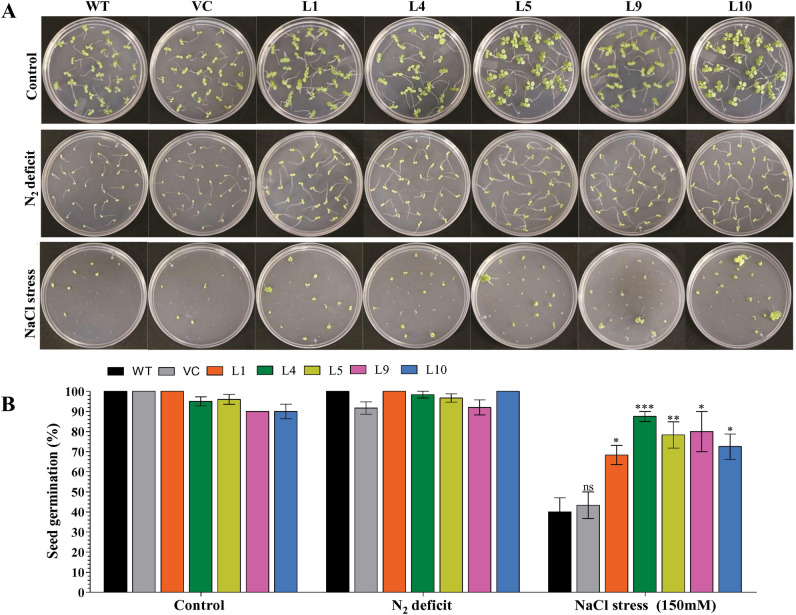

Overexpression of AhCytb6 gene enhances the growth of transgenic under N2 starvation and salt stress

About 100% seed germination was observed under control (unstressed) conditions, and similar results were also found for the N2 starvation condition. However, the percent of seed germination decreased under salt stress. About 40–42% of WT and VC seeds germinated, whereas 65–80% seed germination was estimated for transgenic (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) lines (Fig. 2A, B). Results suggested that the N2 starvation condition did not affect germination, while salt stress severely affects seed germination. Further, the overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene enhanced the seed germination efficiency of transgenic plants under salt stress conditions compared to WT and VC plants.

Figure 2.

Analysis of seed germination of transgenic plants. Comparative analysis of (A) seed germination efficiency and (B) seed germination percentage of selected transgenic lines, WT and VC plants under control, N2 deficit and salt stress condition. Bars represent means ± standard error, and ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ designates for significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively and ‘ns’ represents no significant difference.

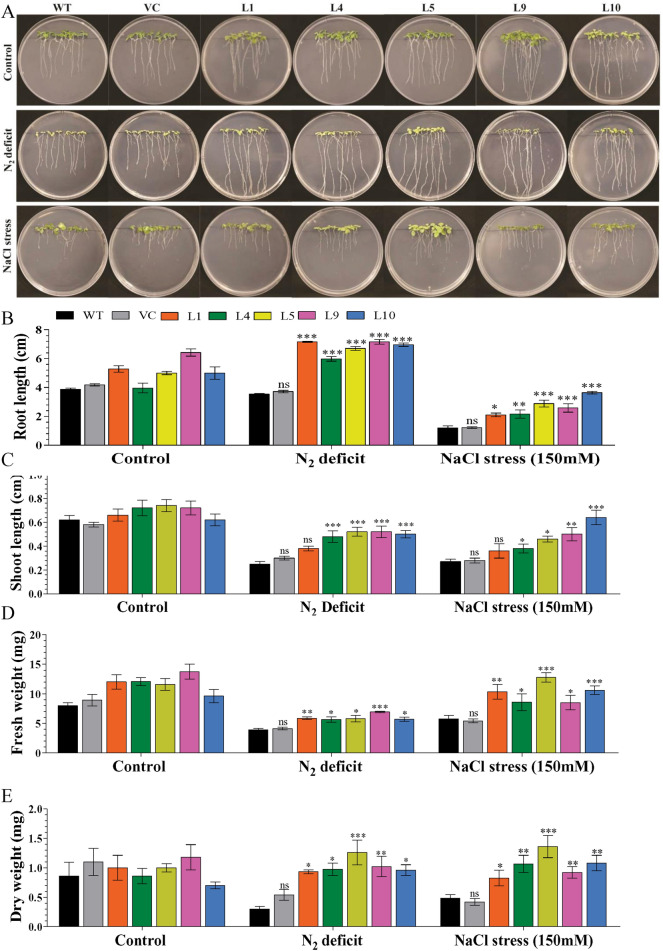

Enhanced plant growth of transgenic plants (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) was observed under stress conditions compared to WT and VC plants (Fig. 3). About 6–7 cm root length (RL), 0.4–0.5 cm shoot length (SL), 6–7 mg fresh weight (FW), and 0.9–1.3 mg dry weight (DW) were estimated in transgenic lines compared to WT and VC plants (RL: 3–4 cm, SL: 0.2–0.3 cm, FW: 3.9–4.1 mg, and DW: 0.3–0.5 mg) under N2 deficit stress conditions. Similarly, higher growth parameters (RL: 2–4 cm, SL: 0.4–0.6 cm, FW: 9–12 mg, and DW: 0.7–1.4 mg) were measured in transgenic plants compared to WT and VC plants (RL: 1–1.2 cm, SL: 0.27–0.28 cm, FW: 5–7 mg, and DW: 0.4–0.5 mg) under salt stress conditions (Fig. 3A–E).

Figure 3.

Analysis of plant growth of transgenic plants. (A) Comparative analysis of seedling growth of selected transgenic lines and control plants under N2 deficit and salt stress condition. (B) Root length, (C) shoot length, (D) fresh weight and (E) dry weight of selected transgenic lines, WT and VC plants under control, N2 deficit and salt stress condition. Bars represent means ± standard error, and ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ designates for significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively and ‘ns’ represents no significant difference.

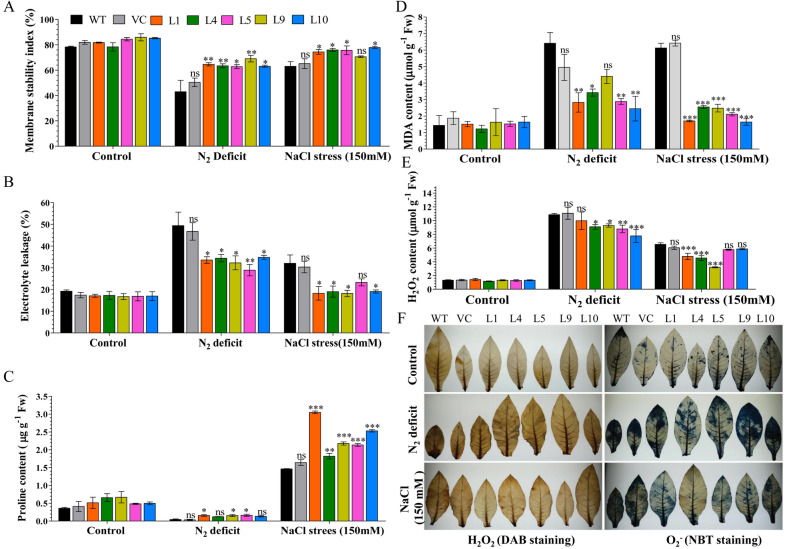

The physiological status of the transgenic plant is modulated by the ectopic expression of the AhCytb6 gene

Improved membrane stability and low electrolyte leakage were found in transgenic lines (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) compared to WT and VC plants under stress conditions (Fig. 4A, B). About 29–35% electrolyte leakage was found in transgenic lines, which were considerably lower than WT and VC plants (47–49%) under N2 deficit conditions. Similarly, lower electrolyte leakage, about 18–23%, was observed in transgenic lines compared to WT and VC plants (30–32%) under salt stress conditions. High membrane stabilities, about 63–69%, and 71–78%, were estimated for transgenic lines under N2 deficit and salt stress conditions, respectively, compared to WT and VC plants (43–50% and 63–65%, respectively). Accumulation of proline, a common physiological response indicator, and a key player in plant abiotic stress tolerance was observed in transgenic plants in N2 deficit and salt stress conditions compared to WT and VC plants (Fig. 4C). Under control conditions, a similar level of proline contents was observed in transgenic lines as well as WT and VC plants. Under N2 deficit conditions, proline contents were about 0.12–0.16 µg g−1 Fw in transgenic plants and about 0.035–0.045 µg g−1 Fw in WT and VC. Under salt stress conditions, about 1.8–3.0 µg g−1 Fw of proline contents were detected in transgenic lines and about 1.4–1.6 µg g−1 Fw in WT and VC plants.

Figure 4.

Physiological status and ROS analysis of transgenic plants. Comparative analysis of (A) membrane stability, (B) electrolyte leakage and (C) proline accumulation (D) lipid peroxidation (MDA content), (E) H2O2 content and (F) in vivo localization of ROS in transgenic lines, WT and VC plants under control, nitrogen deficit and salt stress condition. Bars represent means ± standard error, and ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ designates for significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively and ‘ns’ represents no significant difference.

The AhCytb6 gene protects the plant from ROS buildup during stress conditions

Under control conditions, lipid peroxidation and H2O2 contents were similar in control and transgenic plants. Under N2 deficit condition, transgenic lines (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) showed significantly lower production of MDA (2.5–4.5 µmol g−1 Fw) and H2O2 (8–10 µmol g−1 Fw) in comparison to WT and VC (5–7 µmol g−1 Fw MDA and 11 µmol g−1 Fw H2O2) plants. Similarly, transgenic lines showed significantly lower accumulation of MDA (1.5–2.5 µmol g−1 Fw) and H2O2 (5–7 µmol g−1 Fw) under salt stress condition compared to WT and VC (6–6.5 µmol g−1 Fw MDA and 7 µmol g−1 Fw H2O2) plants (Fig. 4D, E). The above results were further supported by lower in vivo localization of H2O2 and O2- in transgenic leaves compared to their WT and VC counterparts under stress conditions (Fig. 4F).

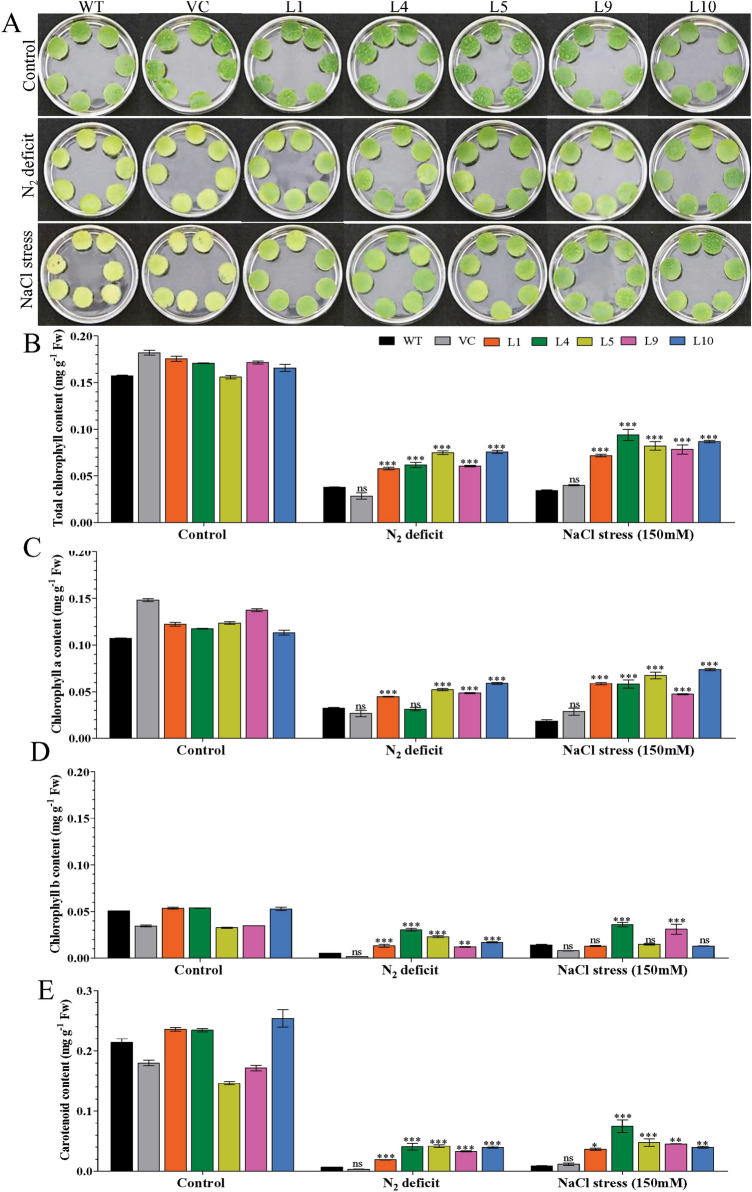

Ectopic expression of the AhCytb6 gene increases the photosynthesis efficiency under stress conditions

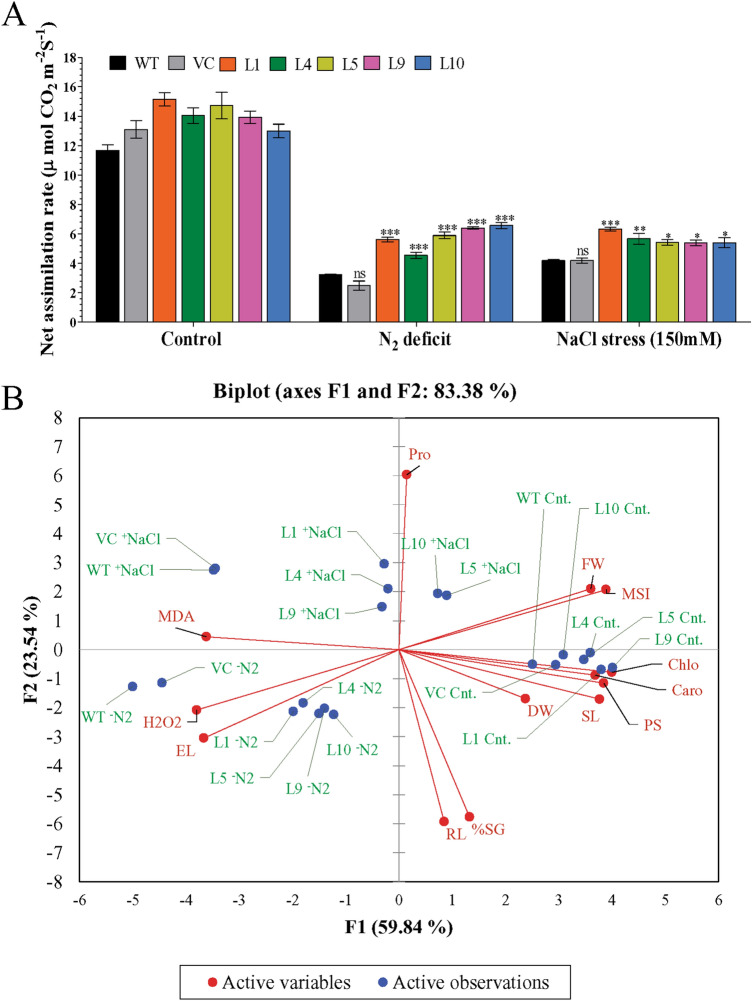

The leaf senescence assay showed a major loss of photosynthetic pigments (bleaching of leaf discs) in WT and VC plants under stress conditions compared to transgenic (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) lines (Fig. 5A). Higher contents of total chlorophyll (0.05–0.07 mg g−1 Fw), chlorophyll a (0.03–0.05 mg g−1 Fw), chlorophyll b (0.01–0.03 mg g−1 Fw), and carotenoids (0.01–0.04 mg g−1 Fw) were estimated in transgenic lines under N2 deficit conditions compared to WT and VC (total chl: 0.02–0.03; chl a: 0.02–0.03; chl b: 0.001–0.005 and carotenoids: 0.003–0.006 mg g−1 Fw) plants. Similarly, higher contents of photosynthesis pigments (total chl: 0.07–0.09; chl a: 0.05–0.07; chl b: 0.01–0.04 and carotenoids: 0.03–0.07 mg g−1 Fw) were found in transgenic lines under salt stress conditions compared to WT and VC (total chl: 0.03–0.04; chl a: 0.01–0.03; chl b: 0.008–0.01 and carotenoids: 0.009–0.01 mg g−1 Fw) plants (Fig. 5B–E). The net photosynthesis of transgenic plants was higher under the stress (5–7 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) environment compared to WT and VC (2–4 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) plants (Fig. 6A). Similarly, stomatal conductance (0.02–0.05 mol H2O m−2 s−1) and transpiration rate (1–1.5 mmol H2O m−2 s−1) were also higher in transgenic compared to WT and VC plants under stress conditions, but it was not significant (Fig. S6). Results confirmed that transgenic plants (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) maintained high photosynthesis under stress conditions compared to WT and VC plants.

Figure 5.

Photosynthesis efficiency analysis of transgenic plants. Comparative analysis of (A) leaf senescence and photosynthetic pigments, (B) total chlorophyll, (C) chlorophyll a, (D) chlorophyll b, (E) carotenoid in transgenic lines, WT and VC plants under control, nitrogen deficit and salt stress condition. Bars represent means ± standard error, and ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ designates for significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

Figure 6.

Photosynthesis efficacy and the principal component analysis of transgenic plants. Comparative analysis of (A) net assimilation in transgenic lines and WT and VC plants under control, nitrogen deficit and salt stress condition, (B) Bi-plot based principal component analysis with first two principal components showing the differential response of transgenic lines and WT plants under un-stress and stress conditions. Bars represent means ± standard error, and ‘*’, ‘**’ and ‘***’ designates for significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively.

Multivariate analysis of morphological, biochemical, and physiological responses of plants

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to distinguish the different responses of transgenic and control plants under normal and stress conditions (Fig. 6B). A bi-plot inferred from the PCA separated plant responses in the first two-component with overall 83.38% variability (PC1: 59.84% and PC2: 23.54%). All plants (transgenic lines and control) showed comparable morphological, biochemical, and physiological responses in the unstressed conditions, as transgenic and WT plants clustered together (cnt) in the bi-plot analysis. Transgenic lines exhibited a differential response to the varying stresses. Among different stress conditions, plants responded towards EL and H2O2 accumulation under N2 deficit conditions compared to salinity stress. Similarly, plants responded further for lipid peroxidation, analyzed by MDA quantification, under salt stress compared to N2 deficit condition. Transgenic lines L5 and L10 were inclined towards proline accumulation under salt stress compared to other lines.

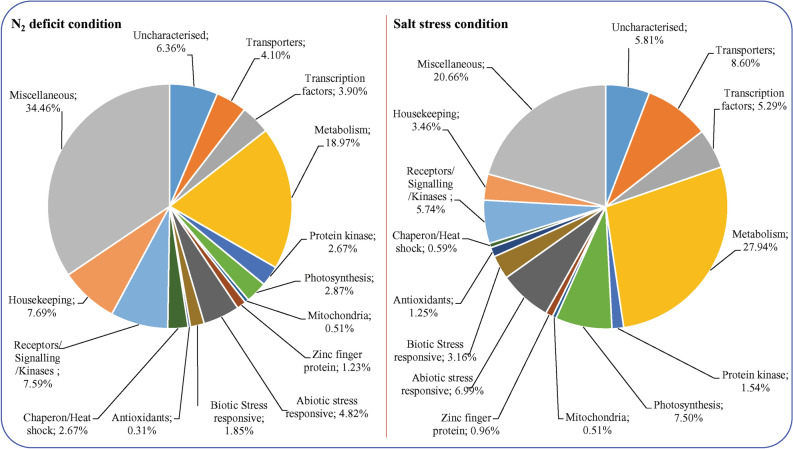

Transcriptional regulation of transgenic tobacco by the AhCytb6 gene under stress condition

The effect of the overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene on the whole-transcript expression of the host plant was studied under stress conditions (N2 deficit and salt stress) using microarray (ArrayExpress ID E-MTAB-9307). The differential expression profiling of 272,410 gene-probes was done, and hierarchical cluster analysis, as well as scatter plots, were analyzed (Fig. S7). The analysis showed out of 272,410 genes, 8,704 and 24,409 genes were significantly (p < 0.05) differentially expressed (> 2 up or down-regulated) under N2 starvation and salt stress conditions, respectively. However, at a 4-fold change level (> 4 up or down-regulated), a total of 975 genes were differentially expressed, with 611 genes up-regulated and 364 genes down-regulated in the treated transgenic plant compared to WT under N2 deficit conditions. Similarly, 1360 genes were differentially expressed in the treated transgenic plant compared to WT under salt stress conditions at a 10-fold change level, out of which 1115 genes were up-regulated while 245 genes were down-regulated (Fig. 7 and Fig. S8). Some of the important differentially expressed genes are listed and grouped into different categories based on their biological activity in Table 1.

Figure 7.

Microarray-based functional classification of host stress responsive genes. Functional classification of differentially expressed genes of AhCytb6 overexpressing transgenic tobacco plant under abiotic stress conditions. Genes differentially expressed in the AhCytb6 plant under stress conditions were normalized with the transcript of WT plants treated with the same stress.

Table 1.

Selected transcripts that differentially expressed (up- or down-regulated) in AhCytb6 overexpressing transgenic tobacco plant compared with the wild type under nitrogen deficit or salt stress conditions.

| S. no. | Transcript probe ID | Gene name | Gene accession | Fold change (log2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcripts significantly differentially expressed under nitrogen deficit stress condition | ||||

| Photosynthesis | ||||

| 1. | NtPMIa1g85328e1_st | RuBisCO large subunit-binding protein | FH655192 | 4.36 |

| 2. | NtPMIa1g189087e1_st | Rubredoxin RubB | FH744456 | 3.88 |

| 3. | NtPMIa1g145438e1_st | Rubisco accumulation factor 2 | FH522410 | 3.72 |

| 4. | NtPMIa1g46069e1_st | Cytochrome P450 | FH898882 | 2.88 |

| 5. | NtPMIa1g14474e2_st | Rubisco accumulation factor 1 | FH386425 | 2.53 |

| 6. | NtPMIa1g72806e3_st | Cytochrome P450, family 704, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | FH034679 | 2.48 |

| 7. | NtPMIa1g32128e1_st | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein 2.1 | FH437542 | – 3.75 |

| 8. | NtPMIa1g121870e1_x_st | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein AB10 | FH174615 | – 2.38 |

| 9. | NtPMIa1g30230e1_st | Cytochrome P450, family 714, subfamily A, polypeptide 2 | FH558936 | – 2.36 |

| 10. | NtPMIa1g95982e1_st | Chlorophyll a/b-binding protein CP24 | FH977269 | – 2.06 |

| 11. | NtPMIa1g156219e1_st | Cytochrome b (mitochondrion) | FH626006 | – 2.02 |

| Transcription factors | ||||

| 12. | NtPMIa1g48630e1_st | Transcription factor | ET758387 | 2.86 |

| 13. | NtPMIa1g169283e1_st | Probable WRKY transcription factor 23 | FH154173 | 2.52 |

| 14. | NtPMIa1g31941e2_st | Heat-inducible transcription repressor | FH029374 | 2.49 |

| 15. | NtPMIa1g100948e1_s_st | Putative transcriptional activator DEMETER | FH999805 | 2.32 |

| 16. | NtPMIa1g173637e1_st | YABBY2-like transcription factor YAB2 | FI080387 | 2.25 |

| 17. | NtPMIa1g63257e1_s_st | Nuclear transcription factor Y subunit A-10 | ET739691 | 2.24 |

| 18. | NtPMIa1g179140e1_st | GATA transcription factor 16 | ET049433 | 2.23 |

| 19. | NtPMIa1g14745e1_st | Probable WRKY transcription factor 4 | FG172186 | 2.12 |

| 20. | NtPMIa1g51042e1_st | Transcription factor ILR3-like | ET854451 | 2.06 |

| 21. | NtPMIa1g58686e1_st | GATA transcription factor 21 | FH630528 | – 2.77 |

| 22. | NtPMIa1g84759e1_s_st | Putative transcription elongation factor SPT5 homolog | FH940966 | – 2.40 |

| 23. | NtPMIa1g5135e1_st | NAC domain containing protein 10 | FH774009 | – 2.31 |

| 24. | NtPMIa1g121208e1_st | MADS-box transcription factor FBP4. | FI070259 | – 2.24 |

| 25. | NtPMIa1g183221e1_st | GATA transcription factor 8-like | FH668641 | – 2.03 |

| Receptors/signalling /Kinases | ||||

| 26. | NtPMIa1g143095e1_st | Receptor lectin kinase | FH976696 | 3.41 |

| 27. | NtPMIa1g120738e1_st | L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinase IV.1 | FI068742 | 3.17 |

| 28. | NtPMIa1g95764e1_st | Concanavalin A-like lectin protein kinase family protein | FH644056 | 2.48 |

| 29. | NtPMIa1g96033e1_s_st | Mannose-binding lectin superfamily protein | FH970974 | 2.25 |

| 30. | NtPMIa1g182212e1_x_st | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 | FH974766 | 2.21 |

| 31. | NtPMIa1g93065e1_x_st | Putative thaumatin-like protein | FH524903 | 2.15 |

| 32. | NtPMIa1g26160e1_st | Serine/threonine-protein kinase-like protein | FH404353 | 2.12 |

| 33. | NtPMIa1g82319e1_st | Serine/threonine-protein kinase | FH087869 | 2.03 |

| 34. | NtPMIa1g74319e1_x_st | LRR receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase | ET908645 | – 2.46 |

| 35. | NtPMIa1g61335e2_st | Calcium-dependent protein kinase | FH408198 | – 2.44 |

| 36. | NtPMIa1g10568e1_st | Calcium-binding protein | FH215122 | – 2.37 |

| 37. | NtPMIa1g122388e1_st | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 15 | FH344502 | – 2.22 |

| Abiotic stress responsive | ||||

| 38. | NtPMIa1g178341e1_st | Auxin-responsive family protein | FH571766 | 2.55 |

| 39. | NtPMIa1g77499e1_st | Cyclic Nucleotide-Regulated Ion Channel Family Protein | EH621839 | 2.34 |

| 40. | NtPMIa1g49198e3_st | Auxin response factor 5 | ET050562 | 2.30 |

| 41. | NtPMIa1g24250e1_st | Auxin-responsive protein IAA6 | ET790168 | 2.24 |

| 42. | NtPMIa1g137731e2_st | Putative chloride channel-like protein Clc-G-Like | FH201280 | 2.11 |

| 43. | NtPMIa1g100401e2_st | Auxin-responsive protein IAA11 | FH994554 | 2.02 |

| 44. | NtPMIa1g36970e1_st | Auxin efflux carrier family protein | ET860447 | – 2.93 |

| 45. | NtPMIa1g176858e1_s_st | Aquaporin PIP2 2 mRNA | ET782162 | – 2.66 |

| Biotic stress responsive | ||||

| 46. | NtPMIa1g176538e1_x_st | Disease resistance protein | FI079692 | 2.94 |

| 47. | NtPMIa1g46074e1_st | NBS-LRR disease resistance protein homologue | FH899274 | 2.28 |

| 48. | NtPMIa1g49587e1_st | Pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily protein | ET051702 | 2.24 |

| 49. | NtPMIa1g57429e1_st | Plant viral-response family protein | ET737281 | 2.11 |

| 50. | NtPMIa1g33021e2_st | Disease resistance protein (TIR-NBS-LRR) family | ET856286 | – 2.13 |

| Antioxidants | ||||

| 51. | NtPMIa1g22665e1_s_st | Superoxide dismutase 3, chloroplastic | FH372649 | 2.38 |

| 52. | NtPMIa1g10068e2_st | Glutathione S-transferase, C-terminal-like | FH199263 | 2.27 |

| Chaperon/Heat shock | ||||

| 53. | NtPMIa1g12414e1_s_st | Chaperonin 60 subunit beta 4, chloroplastic; | ET809635 | 3.08 |

| 54. | NtPMIa1g96842e1_x_st | Heat shock 65 kDa protein | FH979702 | 2.99 |

| 55. | NtPMIa1g99174e1_st | Histone chaperone ASF1B | FH990555 | 2.77 |

| 56. | NtPMIa1g154227e1_s_st | Heat shock 70 kDa protein | FH539518 | 2.44 |

| 57. | NtPMIa1g97529e1_st | Chloroplast Heat Shock Protein 70-2 | FH272606 | 2.08 |

| 58. | NtPMIa1g742e1_s_st | Heat shock protein DnaJ with tetratricopeptide repeats | FH501867 | – 2.22 |

| Transporters | ||||

| 59. | NtPMIa1g35785e3_st | Potassium channel | ET966045 | 2.84 |

| 60. | NtPMIa1g49250e1_st | Peptide transporter 3 | FH083864 | 2.72 |

| 61. | NtPMIa1g51558e1_st | Nodulin MtN21/EamA-like transporter family protein | ET913234 | 2.49 |

| 62. | NtPMIa1g88526e1_st | ABC transporter family protein | FH951768 | 2.46 |

| 63. | NtPMIa1g77463e4_st | Plant calmodulin-binding protein-like protein | ET982476 | 2.38 |

| 64. | NtPMIa1g52615e1_s_st | Putative sugar transporter | EH622321 | 2.37 |

| 65. | NtPMIa1g66400e1_st | Auxin transport protein | FH676020 | 2.26 |

| 66. | NtPMIa1g107239e1_st | Nuclear Transport Factor 2 (Ntf2) Family Protein | FI022849 | 2.09 |

| 67. | NtPMIa1g12413e1_st | K+ transporter 5 | FH098156 | 2.02 |

| Zinc fingers/leucine zipper motifs containing proteins | ||||

| 68. | NtPMIa1g48247e2_st | B-box type zinc finger protein with CCT domain | FH973157 | 3.45 |

| 69. | NtPMIa1g29354e1_st | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein HOX27 | ET042333 | 2.64 |

| 70. | NtPMIa1g7510e1_st | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein HDG12 | ET046033 | 2.38 |

| 71. | NtPMIa1g205801e2_s_st | Putative DHHC-type zinc finger protein | FI045682 | 2.25 |

| 72. | NtPMIa1g12465e1_st | Ring zinc finger protein-like | FH486990 | 2.05 |

| 73. | NtPMIa1g93322e1_st | Zinc finger (C2h2 Type) Family Protein | ET858669 | 2.04 |

| 74. | NtPMIa1g150572e1_st | Zinc finger and hAT dimerization domain | FI059792 | – 2.39 |

| 75. | NtPMIa1g124319e1_st | B-box type zinc finger protein with CCT domain | FH540296 | – 2.15 |

| Unknown/hypothetical/uncharacterized | ||||

| 76. | NtPMIa1g102443e1_st | Uncharacterized | FI004635 | 3.65 |

| 77. | NtPMIa1g18387e2_st | Hypothetical protein | FH373747 | 3.16 |

| 78. | NtPMIa1g16155e1_st | Uncharacterized | ET985839 | 3.10 |

| 79. | NtPMIa1g12003e1_st | Uncharacterized | FH258062 | – 3.53 |

| 80. | NtPMIa1g18678e1_st | Uncharacterized | FG194168 | – 2.56 |

| Transcripts significantly differentially expressed under salt (150 mM NaCl) stress condition | ||||

| Photosynthesis | ||||

| 1. | NtPMIa1g89206e1_st | Cytochrome P450 71A2 | FH116143 | 6.62 |

| 2. | NtPMIa1g77065e1_s_st | Cytochrome P450 | FH044298 | 5.98 |

| 3. | NtPMIa1g167443e1_st | Elicitor-inducible cytochrome P450 (CYP71D20) | ET820462 | 5.78 |

| 4. | NtPMIa1g123263e1_st | Cytochrome b561 | EH620440 | 5.77 |

| 5. | NtPMIa1g31166e2_st | Cytochrome P450, family 71, subfamily B, polypeptide 38 | FH568323 | 4.54 |

| 6. | NtPMIa1g87311e1_st | SufE-like protein 2, chloroplastic | FH948198 | 4.38 |

| 7. | NtPMIa1g119076e1_st | Cytochrome P450, family 76, subfamily C, polypeptide 4 | FH505851 | 3.83 |

| 8. | NtPMIa1g14505e1_st | Cytochrome P450, family 76, subfamily C, polypeptide 3 | FH655318 | 3.65 |

| 9. | NtPMIa1g32128e1_st | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein 2.1, chloroplastic | FH437542 | – 5.86 |

| 10. | NtPMIa1g111798e1_st | Photosystem I light harvesting complex protein | FI040386 | – 5.05 |

| 11. | NtPMIa1g48906e2_st | Photosystem I chlorophyll a/b-binding protein | FH210112 | – 4.71 |

| 12. | NtPMIa1g85781e1_x_st | Light-harvesting complex II chlorophyll a/b-binding protein | FH584622 | – 4.60 |

| 13. | NtPMIa1g34716e1_x_st | Photosystem II light harvesting complex protein | FH010322 | – 4.51 |

| Transcription factors | ||||

| 14. | NtPMIa1g12272e1_s_st | WRKY transcription factor | FH228396 | 6.16 |

| 15. | NtPMIa1g32161e3_st | Transcriptional activator | ET898480 | 3.60 |

| 16. | NtPMIa1g37438e1_st | NAC domain-containing protein | ET867074 | 6.23 |

| 17. | NtPMIa1g84232e2_st | NAC domain-containing protein 72 | FH231367 | 4.18 |

| 18. | NtPMIa1g61499e1_x_st | myb-like transcription factor family protein | FI051254 | 3.41 |

| 19. | NtPMIa1g142252e1_st | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor | FH036716 | 4.04 |

| 20. | NtPMIa1g48202e1_st | BZIP transcription factor bZIP77 | FH071215 | 3.97 |

| 21. | NtPMIa1g6980e1_s_st | MYC transcription factor | FG185704 | – 3.59 |

| 22. | NtPMIa1g62658e1_st | AP2 transcription factor | ET046270 | – 3.46 |

| 23. | NtPMIa1g43983e1_st | Basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor | ET042023 | – 3.41 |

| Receptors/signalling /kinases | ||||

| 24. | NtPMIa1g183983e1_st | Serine/threonine protein kinase 2 | FH678658 | 3.62 |

| 25. | NtPMIa1g10490e2_st | Serine/threonine kinase | FH213282 | 3.58 |

| 26. | NtPMIa1g182617e1_st | G-type lectin S-receptor serine/threonine-protein kinase | FH234969 | 3.42 |

| 27. | NtPMIa1g107535e1_st | Calcium dependent protein kinase | FH688575 | – 3.54 |

| Abiotic stress responsive | ||||

| 28. | NtPMIa1g81893e2_s_st | Abscisic acid-responsive | FH334926 | 5.29 |

| 29. | NtPMIa1g25688e1_st | Hypoxia-responsive family protein | ET710946 | 5.14 |

| 30. | NtPMIa1g65621e1_st | Auxin-induced protein | ET676757 | 5.03 |

| 31. | NtPMIa1g58720e4_st | Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel | FH710343 | 4.53 |

| 32. | NtPMIa1g187181e1_st | K+ efflux antiporter | FH733320 | 4.39 |

| 33. | NtPMIa1g80304e1_st | Aquaporin | FH517170 | 4.11 |

| 34. | NtPMIa1g82556e4_st | Water channel protein MipK | ET846459 | 4.09 |

| 35. | NtPMIa1g87091e3_s_st | Early-responsive to dehydration protein | ET815593 | 3.69 |

| 36. | NtPMIa1g174261e1_s_st | Calmodulin | FH113769 | 3.69 |

| 37. | NtPMIa1g94367e1_st | Calcium binding protein | FG176020 | 3.64 |

| 38. | NtPMIa1g183329e1_x_st | Sodium/calcium exchanger membrane region | FI080543 | 3.61 |

| 39. | NtPMIa1g100023e1_s_st | Late embryogenesis abundant protein D-29 | FH993271 | 3.51 |

| 40. | NtPMIa1g52217e3_st | K+ uptake permease | FH496325 | 3.34 |

| 41. | NtPMIa1g46641e1_st | Senescence-associated gene | ET683467 | – 3.95 |

| 42. | NtPMIa1g25579e1_st | Senescence-inducible chloroplast stay-green protein | FH985884 | – 3.55 |

| Biotic stress responsive | ||||

| 43. | NtPMIa1g50893e1_x_st | Pathogen induced protein uncharacterized | FH017913 | 5.30 |

| 44. | NtPMIa1g446e2_s_st | Pathogenesis-related transcriptional factor and ERF | FI004101 | 3.86 |

| 45. | NtPMIa1g73165e2_s_st | Pathogen induced protein | ET724700 | 3.80 |

| 46. | NtPMIa1g89450e2_st | Putative verticillium wilt disease resistance protein Ve2 | ET690367 | 3.76 |

| 47. | NtPMIa1g11236e2_st | Pathogenesis-related protein Q (PR-Q) | EH618316 | 3.35 |

| Antioxidants | ||||

| 48. | NtPMIa1g2398e1_s_st | ACC oxidase | FH038492 | 5.83 |

| 49. | NtPMIa1g285e1_s_st | Glutathione S-transferase | FH948778 | 5.24 |

| 50. | NtPMIa1g107555e1_s_st | l-ascorbate oxidase | FH518217 | 4.16 |

| 51. | NtPMIa1g116765e2_st | Ascorbate oxidase | FI055586 | 3.39 |

| 52. | NtPMIa1g100148e1_x_st | Ascorbate peroxidase | FG199962 | 3.34 |

| Chaperon/heat shock | ||||

| 53. | NtPMIa1g122482e1_st | mitochondrial chaperone | EH622598 | 5.25 |

| 54. | NtPMIa1g80636e4_st | chaperone protein chloroplastic | ET703308 | 4.89 |

| 55. | NtPMIa1g48639e1_st | Heat shock 70 kDa protein | FH643753 | 4.16 |

| Transporters | ||||

| 56. | NtPMIa1g45198e1_s_st | Sugar transport protein | ET923251 | 5.92 |

| 57. | NtPMIa1g179293e1_st | ABC protein | FH628071 | 5.36 |

| 58. | NtPMIa1g36079e1_st | Amino acid transporter | FH005832 | 4.53 |

| 59. | NtPMIa1g58619e1_st | Sulfate transporter | FG143420 | 4.36 |

| 60. | NtPMIa1g12338e2_s_st | Ammonium Transporter 2 | ET797276 | 4.02 |

| 61. | NtPMIa1g170644e1_st | High affinity K+ transporter | FH538430 | 3.64 |

| 62. | NtPMIa1g202149e1_st | Nitrate transporter NRT1-5 | ET806108 | 3.38 |

| 63. | NtPMIa1g193197e1_s_st | Sugar phosphate exchanger, putative | FH747309 | – 4.11 |

| Zinc fingers/leucine zipper motifs containing proteins | ||||

| 64. | NtPMIa1g102701e1_st | Zinc induced facilitator | FH079466 | 6.01 |

| 65. | NtPMIa1g95486e1_st | Zinc finger protein CONSTANS | FH975799 | 5.69 |

| 66. | NtPMIa1g34050e1_st | Zinc finger CCCH domain | FH744808 | 3.35 |

| 66. | NtPMIa1g227029e1_st | Zinc finger B-box protein | FG167857 | 4.06 |

| 68. | NtPMIa1g68098e1_st | DHHC-type zinc finger family protein | FG197147 | 3.43 |

| 69. | NtPMIa1g31503e1_s_st | b-box type zinc finger protein with CCT domain | ET051218 | – 3.97 |

| Unknown/hypothetical/uncharacterized | ||||

| 70. | NtPMIa1g8438e1_st | Uncharacterized | FH583256 | 7.71 |

| 71. | NtPMIa1g110238e3_s_st | Hypothetical protein | FG133280 | 5.19 |

| 72. | NtPMIa1g197992e1_st | Uncharacterized transporter | ET761936 | 5.16 |

| 73. | NtPMIa1g191871e1_st | Uncharacterized | FH009504 | – 8.35 |

| 74. | NtPMIa1g100379e1_st | Hypothetical protein | ET829011 | – 6.03 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| 75. | NtPMIa1g38846e1_st | Early flowering-like protein | ET778187 | 4.85 |

| 76. | NtPMIa1g36370e1_st | Early nodulin-like protein | FH240198 | 4.79 |

| 77. | NtPMIa1g35320e3_s_st | Nodulin family protein | FI036052 | 4.53 |

| 78. | NtPMIa1g51558e1_st | Nodulin/EamA-like transporter family protein | ET913234 | 3.72 |

No sign indicates up-regulation, whereas “−” sign shows down-regulation. Fold-expression is significant at ANOVA p < 0.05.

Discussion

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) is considered an attractive way for sustainable agriculture to cope up with biotic and abiotic stresses. However, due to difficulties in practical implication, handling in field conditions, and comparatively slow response, alternative ways are much needed27. The gene(s) that are differentially over-expressed in host plants in the response of plant-microbe (PGPR) interaction could be potential candidates to be explored to engineer crops for future agriculture under different stress conditions. Keeping this thought in mind, we have identified and clone genes that are differentially expressed in peanut (host plant) in the response of interaction with PGPR (S. maltophilia) under the N2 starvation conditions (Fig. 1). These differentially expressed genes could be utilized to improve crop productivity in nitrogen-deficient and salt-affected areas. In a previous study, we reported that S. maltophilia BJ01 modulates the physiology of peanut plants to protect them under nitrogen deficiency and salt stress conditions19,20. In this study, first and foremost we identified the differentially expressed gene due to interaction of S. maltophilia BJ01 under nitrogen starvation condition.

PCR-based cDNA subtraction, commonly known as suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH), is a powerful method for selectively amplification of differentially expressed target cDNA and at the same time, non-targeted DNA amplification is suppressed28. The SSH result showed that about 60% of differentially expressed genes were of unknown/uncharacterized function. Expression of a large number of uncharacterized or hypothetical genes after interaction with PGPR under the N2 deficit condition provides a molecular insight of changes that occurs during the interaction of S. maltophilia and A. hypogaea. In contrast, the interaction between Cicer arietinum and Ascochyta rabiei resulted in 7% genes of unknown function29, whereas the interaction between Vitis pseudoreticulata with Uncinula necator leads to the differential expression of 24% uncharacterized genes30. These N2 starvation-responsive genes were further validated by qRT-PCR, and the expression profiling of these uncharacterized SSH clones showed that these genes were up-regulated during plant interaction with S. maltophilia (Fig. S1). An N2 deficiency and PGPR interaction responsive clone SM409 (later on named the AhCytb6 gene, which shows the similarity with PSII related gene cytb6), had higher expression (about 4-fold) among studied clones in a transcript profiling and was selected to characterize further in a model plant tobacco. Fataftah et al. showed that 1938 genes were differentially expressed in barley leaves after 20 days of nitrogen starvation; when plants were resupplied with nitrogen, 62% of genes that were down-regulated were up-regulated and out of these genes, most of the genes belong to photosynthesis31. The RNAseq data of Yang et al. showed that the Cytb/f complex is upregulated in leaves of low nitrogen level tolerance verity of sugarcane; both studies indicate the involvement of Cytb6 gene in nitrogen deficit condition32. Thus, this study also supports the major role of photosynthetic related genes in the case of nitrogen starvation. In contrast, PSII related genes were downregulated in durum wheat under nitrogen starvation conditions33. Thus, differential expression of gene under N2 starvation is due to interaction with the S. maltophilia and helps plants to cope up with the nitrogen starve condition. The genome organization study confirmed that the AhCytb6 gene is intronless, and in-silico analysis revealed that the gene encodes for a transmembrane protein consisting of helix and coil motifs that is highly stable (Figs. S3–S4).

All raised transgenic lines were checked for the confirmation of transgene, and out of 17 transgenic lines (Fig. 1), we selected five lines showing single transgene integration with the high expression for further analysis under stress conditions. Overexpression of AhCytb6 improved seed germination and health of the growing seedlings under N2 starvation and salt stress conditions where WT and VC failed to do so (Figs. 2, 3). Transgenic seedlings grown in stress conditions exhibited higher shoot length, root length, fresh weight, and dry weight in comparison to WT and VC (Fig. 3). The enhanced germination and growth of the transgenic plants showed that the AhCytb6 gene increases the tolerance against N2 starvation and salt stress by restoring the photosynthetic machinery and equilibrating C:N ratio, which is important during the reproductive and growth period of the plant. In another study, Qiao et al. showed that Cytochrome b561 was differentially expressed and up-regulated in pigeon pea after interaction with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under drought, which supports the role of the cytb6 gene in legumes in the symbiotic relationship under abiotic stress condition34. On the other hand, Dyda et al. showed that cytochrome b559 was down-regulated in triticale after infection with pathogenic fungus Microdochium nivale, which showed that gene cytb has a crucial role in plant immunity35. Joaquín-Ramos et al. showed that CYTb6f was significantly up-regulated in Amaranthus cruentu under salt stress (300 mM) which supports the role of cytb6 under salt stress36. Constitutive expression of rice microRNA528 also showed enhanced growth, elevated biomass, and tolerance to salinity stress and N2 starvation in the transgenic plants37.

The physiological status of the plant determines growth and survival during harsh environmental conditions. Abiotic stress damages the plant cell membrane, integrity of the cell membrane is essential for the stress tolerance of the plant. Results of EL and MSI showed that all transgenic plants overexpressing the AhCytb6 gene had less cell membrane injury compared to WT and VC plants (Fig. 4). Thus, increased membrane stability and a low level of electrolyte leakage help the plant to maintain the cell homeostasis under stress conditions; similar results were obtained by Ben-Romdhane et al.38. Proline is an essential osmolyte and molecular chaperon, which helps the plant to maintain the cytosolic redox status and ROS scavenging as well as helping the plant under stress conditions39,40. The transgenic plant overexpressing the AhCytb6 gene enhanced the proline production in transgenic plants and enabled plants to mitigate the stress conditions at the cellular level.

The ROS metabolism in the cell is regulated by redox mechanisms with the help of antioxidants, and it maintains the stable dynamic equilibrium in normal physiological conditions41. Under stress conditions, this balance is disrupted and creates oxidative stress, which can cause damage to nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids42,43. When living cells face stress, they generate free radicles like superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and cell membranes (which are made up of fatty acids) prone to oxidation. These free radicles cause peroxidation of the cell membrane and generate malondialdehydes (MDA); thus, these parameters are used for the biochemical markers to measure the stress levels44. Abiotic stress causes disturbance in PSII, which causes the generation of a high amount of ROS; here overexpression of AhCytb6 may provide stability to ETC and cause a reduction in ROS in transgenic lines. The WT and VC plants accumulate more MDA, H2O2, and O2- in comparison to transgenic plants (Fig. 4). Thus, results confirmed the role of AhCytb6 in ROS scavenging in plants and stress tolerance of N2 starvation and salt stress conditions. Recently, Yang et al. also showed that transgenic tobacco lines overexpressing chloroplast targeting and heme-binding genes AhFC1 and AhHEMA1 had less accumulation of MDA, H2O2 content in comparison to the wild-type under 200 mM salt stress conditions45. This finding also supports the role of chloroplast targeting and cytochrome-related genes in plant defense mechanisms other than photosynthesis.

Salt stress can cause damage to the chlorophyll pigment-protein complex and degrades the enzyme chlorophyllase, and nitrogen starvation causes chlorosis in leaves46,47. Chlorophyll contents observed under salt and N2 deficit condition showed that the transgenic plants were able to retain more chlorophyll contents and carotenoids in comparison to the WT and VC counterparts (Fig. 5). A higher concentration of carotenoid content in transgenic lines is an indicator of better photosynthetic efficiency as well as reduced oxidative stress in stressed conditions because carotenoid also plays a protective role against ROS48. It is quite evident that AhCytb6 protects plants from the loss of chlorophyll and helps the information of vital pigments via improving performance in photosynthesis. Under low nitrogen, plants reduce their photosynthesis to reduce energy loss; we found that the net photosynthesis rate was significantly higher in the transgenic plants in N2 starvation in comparison to WT and VC. Electron transport is very much affected during photosynthesis by high salt concentration and/or nitrogen starvation, which deteriorates the photosynthetic performance of plants23,49. In our study, transgenic lines overexpressing the Ahcytb6 gene has a higher net photosynthesis rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate than WT and VC show that the AhCytb6 gene plays a key factor in PSII and enhances photosynthesis efficiency and yield of the plant under stress (Fig. 6A and Fig. S6). Similar activity of the OsPGK2-P gene was also reported in transgenic tobacco under salt stress50.

Microarray analysis of the plant overexpressing the AhCytb6 gene showed differential expression of the gene compared to the WT plant in similar stress conditions. Our results showed that the ectopic expression of AhCytb6 influenced the expression of genes belonging to metabolism (28%), transporters (9%), photosynthesis (7%), abiotic stress-responses (7%), receptor/kinase/signaling (7%), uncharacterized (6%), transcription factors (5%), biotic stress (3%), antioxidant (1%), and chaperon/heat shock protein (1%). Besides this, miscellaneous (21%) and housekeeping (3%) were also differentially expressed under salt stress. Results coincided with the study of Passricha et al.51, where transporters, kinases, and genes related to abiotic stress were also differentially expressed in transgenic rice overexpressing the PsLecRLK gene under salt stress. Under N2 starvation conditions metabolism (19%), transporter (4%), photosynthesis (3%), abiotic stress-responsive (5%), receptor/kinase/signaling (8%), uncharacterized (6%), transcription factors (4%), biotic stress (2%), and chaperon/heat shock protein (3%) along with miscellaneous (34%) and housekeeping (8%) were also differentially expressed.

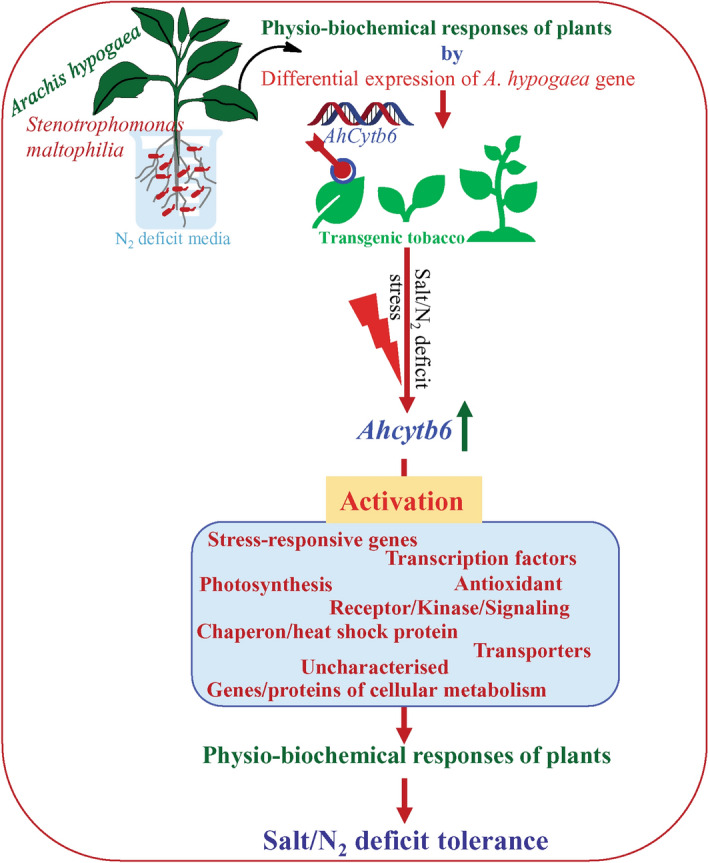

Transgenic tobacco overexpressing wheat microRNA TaMIR444a led to the differential expression of 1733 genes in compression of WT under N2 starvation. These genes belonged to unknown, transcription, transportation, abiotic and biotic stress, signaling, metabolism, and a miscellaneous category52. Microarray data show that overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene affects the plant response in nitrogen starvation and salt stress at the molecular level, these changes cumulatively support a plant under stress condition, and transgenic lines perform better than the wild-type counterparts do. Overexpression of abiotic and biotic stress-related genes and heat shock proteins show that this gene can play important role in priming plant immunity under biotic and abiotic stresses. In a study by Luo et al., nitrogen availability is directly proportional to the differential overexpression of photosynthesis-related genes53. In contrast to this, due to the overexpression of the Cytb6 gene, 3% of photosynthetic genes were differentially expressed under N2 starvation, showing the role of this gene in N2 assimilation, which follows a recent study of Iqbal et al.54. Overexpression of transcription factors like WRKY, GATA, YAB2 under N2 starvation and WRKY, NAC, MYB, under salt stress show that the Cytb6 gene plays a major role in C–N metabolism and in salt stress that starts at the transcription level. Rubisco, which is an indicator for total N2 level in plants and leaves, also up-regulates in transgenic plants under salt and N2 starvation showing the balancing role of Cytb6 in the C–N cycle in stress conditions. Similar results were observed by Xin et al.55. Based on the above results, we hypothesized a model that summarized the probable role of AhCytb6 in plant-microbe interaction and abiotic stress tolerance (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A hypothetical schematic model explaining the probable role of the AhCytb6 abiotic stress tolerance system.

Conclusion

In this study, we reported the changes at the molecular level in the host plant after plant-microbe interaction. AhCytb6 is a photosynthetic gene differentially expressed after interaction between Arachis hypogaea–Stenotrophomonas maltophilia under N2 stress. This gene plays a significant role in plant-microbe interaction, and its role is functionally validated by ectopic overexpression in transgenic tobacco plants. Morphology, physiology, biochemical, and genetic parameters were analyzed under N2 starvation and salt stress conditions and compared to their wild-type counterparts. We observed that transgenic plants perform better under stress conditions than WT and VC. Overexpression of this gene enhanced endurance against N2 starvation and salt stress. Microarray analysis of transgenic plants showed that this gene also affects the transcript expression of different stress-responsive genes and transcription factors. Overall results reveal roles of AhCytb6 in stress tolerance under N2 deficit and salt stress other than photosynthesis. This gene could be further explored for the development of genetically modified crops for sustainable agriculture under N2 deficits and/or salt-affected areas.

Materials and methods

PGPR treatment to the peanut plant

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) seeds (cultivar GG-20) were obtained from the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh (Gujarat), which also have the voucher specimen for the identification of plants. Procure peanut seeds were surface sterilized, germinated, and transferred to previously optimized hydroponics conditions19,56. Briefly, seven days old seedlings were transferred 300 mL ½ MS media supplemented without nitrogenous component. Plants were treated with plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium S. maltophilia BJ01, which has proven ability to provide plant tolerance under N2 deficit conditions19. Plants were grown under the N2 starvation condition with (T) or without bacterial inoculation (C) for 21 days. Plant leaves were collected after 21 days and stored at − 80 ℃ for further experiments.

Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) and dissemination of differentially expressed gene(s)

Total RNA was isolated from control and treated plants by guanidine isothiocyanate (GITC) method, and mRNA was purified using Poly AT tract mRNA isolation kit following the manufacturer's instruction (Promega, USA). Total 2 µg mRNA was used for single stranded cDNA synthesis using 1 mM primer (5′-TTT TGT ACA AGC TT30 N1N-3′ containing Rsa I restriction sites; GTAC), 1 mM deoxynucleotides (dNTPs), and 20 units of avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase. Immediately after completion of single stranded cDNA, proceed for the double stranded cDNA synthesis at 16 ℃ in thermal cycler using 0.2 mM dNTPs mix, a second strand enzyme cocktail (containing DNA polymerase I, RNase H and DNA ligase) and 6 unit of T4 DNA polymerase57. The cDNA, synthesized from the treated plant was considered as a ‘tester’ while the cDNA of the control plant was used as a ‘driver.’

Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) was performed with a PCR-Select cDNA Subtraction Kit according to the user manual (Clontech, USA). In brief, the blunt end was created in driver and tester double-stranded cDNAs by Rsa I restriction digestion. The tester cDNA was purified and subdivided into two sets, and each was ligated with different adaptors at 16 ℃ for 12 h. However, driver cDNAs were not ligated with any adapters. Hybridization of tester and driver cDNA was carried out in two steps; in the first step, digested driver cDNA was added to individual adapter-ligated tester cDNA, denatured at 98 ℃ for 90 s and allowed for hybridization at 68 ℃ for 8 h. In the second step, both hybridized products were mixed, and the fresh denatured driver cDNA was added and allowed for hybridization again. Differentially expressed cDNAs were exponentially amplified using adapter-specific primers, cloned in pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, USA) and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells57. Positive clones were selected, confirmed, sequenced (at M/s Macrogen Inc., South Korea), and analyzed by bioinformatics tool.

Selection and transcript profiling of differentially expressed genes

Differentially expressed genes obtained by SSH were categorized, and representative primer sets were designed for each category (Table S1). Total RNA was isolated (from control and treated plants), and cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg of total RNA using the ImProm‐II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA). Quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR reaction was performed with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, USA) in a Bio-Rad CFX96 detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). The specificity of qRT-PCR was determined by melt curve analysis followed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The relative fold expression of genes was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method58, while actin was used as the housekeeping gene.

A clone SM409 (538 bp), which was classified in the unknown category (showing resemblance with unknown mRNA from NCBI database), and showed about 4-fold up-regulation in the treated plant (compared to the control under stress conditions), was selected for the further study.

Cloning of gene and bioinformatics analysis

Deferentially expressed gene SM409 was made full by rapid amplification of cDNA ends, cloned in pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, USA), transformed to E. coli DH5α cells, and sequenced (at M/s Macrogen Inc., South Korea). The contiguous sequences obtained through RACE (3′RACE and 5′RACE) were assembled to obtain the full-length gene sequence. The gene-specific primer (Table S2) was designed, and a full-length gene was amplified from the cDNA of A. hypogaea using proof-read (Pfu) polymerase, cloned in pGEM-T easy vector and sequenced (M/s Macrogen Inc., South Korea). The sequence was analyzed using different bioinformatics tools available at the ExPASY portal. Based on different bioinformatics analyses, the SM409 clone sequence was named as the AhCytb6 gene.

Genetic transformation of tobacco and generation of transgenic plants for the functional analysis of AhCytb6 gene

The complete coding region of the AhCytb6 gene was amplified (Table S2) and cloned into the pRT100 vector down-stream to the 35S promoter. Recombinant pRT100 (pRT100:AhCytb6) was digested with enzyme PstI, expression cassette (35S:AhCytb6:35S-ter) was obtained and cloned in pCAMBIA2301 vector. The resultant plant expression vector pCAMBIA2301:35S:AhCytb6 was mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 for the genetic transformation. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Nicotiana tabacum cv. Petit Havana with the AhCytb6 gene was done using the leaf disc transformation method59. After genetic transformation, leaf disc was regenerated as per standard tissue culture protocol, putative transgenic lines (T0) were screened on kanamycin (50 mg L−1) for the selection, positive plants were transferred in the greenhouse under controlled condition, and matured seeds (T0) were collected60,61.

Analysis of transgenic lines under different abiotic stress condition

Transgenic seeds were germinated on kanamycin (50 mg L−1), and T1 transgenic lines were obtained. Transgene integration was confirmed by PCR amplification of uidA (GUS) and AhCytb6 gene (Table S2); however, transgene event (copy number) was checked by southern blot analysis. Transgenic lines were subjected for histochemical GUS analysis, and five lines (L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10) were selected, and overexpression of the AhCytb6 gene was analyzed by semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (Table S2). The selected transgenic lines were studied for morphological, biochemical and physicochemical analyses, and compared with wild-type (WT: untransformed tobacco plant) and vector control (VC: transgenic lines transformed with pCAMBIA2301 vector) plants under different abiotic stress treatments. Germination efficiency (% germination) of transgenic lines were studied under N2 starvation and NaCl (150 mM) stress conditions.

For the morphological study, seeds (transgenic lines, WT and VC) were germinated on MS media supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg L−1), and 3 days old equal size seedlings were transferred to different petri-plates (containing MS media) and subjected to N2 starvation and NaCl (150 mM) stress conditions for 21 days (8 h dark/16 h light cycle at 25 °C). Growth parameters were measured and documented62. For stress treatments, 21 days-old seedlings (grown on MS media supplemented with kanamycin) were transferred to hydroponics (containing ½ strength of MS media without N2 source) and grown further 21 days under N2 starvation conditions. In a parallel set of experiment, forty-two days old plants grown under normal conditions (1/2 MS media without any stress) were subjected to NaCl (150 mM) stress conditions for 24 h. Plants (transgenic lines: L1, L4, L5, L9, and L10; WT and VC) grown under control (without any stress) or different stress conditions (N2 deficit and NaCl stress) were harvested and studied for different morphology, biochemical and physiological analyses.

Leaves disc (~ 8 mm) of plants (42 days) grown (as above) under control (unstressed) conditions were subjected to different stresses (N2 deficit and NaCl stress) conditions for 7-days. Leaf senescence was documented, whereas chlorophyll and carotenoids were measured56. Comparative physio-biochemical analyses, including, electrolyte leakage, membrane stability index, proline, lipid peroxidation (MDA) content and H2O2 content were performed for all harvested plants63-68. The in vivo localization of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and supero xide radicals (O2−) was done by histochemical staining69. Photosynthesis parameters, including net assimilation rate, stomatal conduct ance, and transpiration rate, were measured by portable photosynthesis (LI6400XT, LI-COR Biosciences, USA) system62.

Expression profiling of transgenic plants by microarray

A transgenic plant that performed better compared to other lines was selected for the differential transcript expression profiling62,70. Forty-two days old plant grown under N2 starvation (21 days) stress condition and a plant (42-days old) subjected to NaCl (150 mM for 24 h) stress were used for microarray analysis along with corresponding control plants. Total RNA was extracted from treated and WT (unstressed) plants and converted to first strand cDNA followed by second strand cDNA synthesis. In vitro transcription was performed and a cRNA was synthesized and finally converted to single-stranded cDNA. Single-stranded cDNA was fragmented, labeled and hybridized with a whole gene tobacco array, which was comprised of 272,410 gene probes. Hybridization was performed at 42 °C for 16 h, according to the user manual (Affymetrix, USA). After hybridization, the array chip was washed and stained in the fluidics module (Fluidics Station 450, Affymetrix, USA), scanned (Scanner 3000 7G, Affymetrix, USA), and analyzed using expression console (version 1.1) and transcriptome analysis console (version 3.0) software (Affymetrix, USA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicates, and each set of experiments contained five plants (except microarray, which was performed in duplicate). Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism software. All data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett test to compare all column vs WT in each condition. Values are expressed as the mean ± SE, and p value < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Prof. Bhavanath Jha is thankfully acknowledged for securing initial funds to support this research. This work was funded from SERB-DST (EMR/2016/000538) and CSIR-Young Scientist (YSP-02/2016-17) projects. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. CSIR-CSMCRI Communication No.: PRIS-78/2020.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: A.M.; Performed the experiments: A.A. and V.S.; Analyzed the data: A.A., V.S. and A.M.; Wrote the manuscript: A.A., V.S., and AM.

Data availability

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article and supplementary data. Microarray data are available in the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-9307.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-92424-4.

References

- 1.Van Loon LC. Plant responses to plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. In: Bakker PAHM, Raaijmakers JM, Bloemberg G, Höfte M, Lemanceau P, Cooke BM, editors. New perspectives and approaches in plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria research. Springer; 2007. pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vessey JK. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers. Plant Soil. 2003;255:571–586. doi: 10.1023/A:1026037216893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Wees SC, Van der Ent S, Pieterse CM. Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008;11:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stringlis IA, Proietti S, Hickman R, Van Verk MC, Zamioudis C, Pieterse CM. Root transcriptional dynamics induced by beneficial rhizobacteria and microbial immune elicitors reveal signatures of adaptation to mutualists. Plant J. 2018;93:166–180. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field CB. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. In: Field CB, Dahe Q, Stocker TF, Barros V, editors. Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2012. pp. 1–582. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinclair TR, Vadez V. Physiological traits for crop yield improvement in low N and P environments. Plant Soil. 2002;245:1–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1020624015351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate RL. Soil Microbiology. 2. Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lian X, Wang S, Zhang J, Feng Q, Zhang L, Fan D, Li X, Yuan D, Han B, Zhang Q. Expression profiles of 10,422 genes at early stage of low nitrogen stress in rice assayed using a cDNA microarray. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;60:617–631. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-5441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu GH, Zhuang CX, Wang YQ, Jiang LR, Peng XX. Differential expression of rice genes under different nitrogen forms and their relationship with sulfur metabolism. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006;48:1177–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu T, Ren T, White PJ, Cong R, Lu J. Storage nitrogen co-ordinates leaf expansion and photosynthetic capacity in winter oilseed rape. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:2995–3007. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabra A, et al. Interaction among Arachis hypogaea L. (peanut) and beneficial soil microorganisms: How much is it known? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;36:179–194. doi: 10.3109/10408410903584863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora S. Microbial approach for remediation and health management of salt affected soils. In: Pareek NK, Arora S, editors. Natural Resource Management in Arid and Semi-arid Ecosystem for Climate Resilient Agriculture. New Delhi: Soil Conservation Society of India; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharyya PN, Jha DK. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28:1327–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshmukh Y, Khare P, Patra D. Rhizobacteria elevate principal basmati aroma compound accumulation in rice variety. Rhizosphere. 2016;1:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etesami H, Alikhani HA. Co-inoculation with endophytic and rhizosphere bacteria allows reduced application rates of N-fertilizer for rice plant. Rhizosphere. 2016;2:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2016.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vleesschauwer D, Cornelis P, Höfte M. Redox-active pyocyanin secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2 triggers systemic resistance to Magnaporthe grisea but enhances Rhizoctonia solani susceptibility in rice. Mol. Plant Microbe Int. 2006;19:1406–1419. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahkami AH, White RA, III, Handakumbura PP, Jansson C. Rhizosphere engineering: Enhancing sustainable plant ecosystem productivity. Rhizosphere. 2017;3:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2017.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh VK, Kavita K, Prabhakaran R, Jha B. Cis-9-octadecenoic acid from the rhizospheric bacterium Stenotrophomonas maltophilia BJ01 shows quorum quenching and anti-biofilm activities. Biofouling. 2013;29:855–867. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2013.807914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander A, Singh VK, Mishra A, Jha B. Plant growth promoting rhizobacterium Stenotrophomonas maltophilia BJ01 augments endurance against N2 starvation by modulating physiology and biochemical activities of Arachis hypogea. PloS One. 2019;14:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander A, Singh VK, Mishra A. Halotolerant PGPR Stenotrophomonas maltophilia induces salt tolerance by modulating physiology and biochemical activities of Arachis hypogaea. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:2530. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.568289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruuska SA, Andrews TJ, Badger MR, Price GD, von Caemmerer S. The role of chloroplast electron transport and metabolites in modulating Rubisco activity in tobacco. Insights from transgenic plants with reduced amounts of cytochrome b/fcomplex or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:491–504. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu H, Zeng LD, Yi XP, Peng CL, Zhang WF, Chow WS. The half-life of the cytochrome bf complex in leaves of pea plants after transfer from moderately-high growth light to low light. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017;44:351–357. doi: 10.1071/FP16222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lande NV, Barua P, Gayen D, Kumar S, Varshney S, Sengupta S, Chakraborty S, Chakraborty N. Dehydration-induced alterations in chloroplast proteome and reprogramming of cellular metabolism in developing chickpea delineate interrelated adaptive responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020;146:337–348. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chida H, Nakazawa A, Akazaki H, Hirano T, Suruga K, Ogawa M, Satoh T, Kadokura K, Yamada S, Hakamata W, Isobe K. Expression of the algal cytochrome c6 gene in Arabidopsis enhances photosynthesis and growth. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:948–957. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hura T, Hura K, Ostrowska A, Gadzinowska J, Grzesiak MT, Dziurka K, Dubas E. Rieske iron-sulfur protein of cytochrome-b6f is involved in plant recovery after drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018;156:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ermakova M, Lopez-Calcagno PE, Raines CA, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. Overexpression of the Rieske FeS protein of the Cytochromeb6f complex increases C 4 photosynthesis in Setaria viridis. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander A, Mishra A, Jha B. Halotolerant rhizobacteria: A promising probiotic for saline soil-based agriculture. In: Kumar M, Etesami H, Kumar V, editors. Saline Soil-Based Agriculture by Halotolerant Microorganisms. Springer; 2019. pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diatchenko L, et al. Suppression subtractive hybridization: A method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996;93:6025–6030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaiswal P, et al. Differential transcript accumulation in chickpea during early phases of compatible interaction with a necrotrophic fungus Ascochyta rabiei. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:4635–4646. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi JL, Wang YJ, Zhu ZG, Zhang CH. The EST analysis of a suppressive subtraction cDNA library of Chinese Wild Vitis pseudoreticulata inoculated with Uncinula necator. Agric. Sci. China. 2010;9:233–241. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60088-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fataftah N, Mohr C, Hajirezaei MR, von Wirén N, Humbeck K. Changes in nitrogen availability lead to a reprogramming of pyruvate metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:77. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Gao S, Su Y, Lin Z, Guo J, Li M, Wang Z, Que Y, Xu L. Transcripts and low nitrogen tolerance: Regulatory and metabolic pathways in sugarcane under low nitrogen stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019;163:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curci PL, Cigliano RA, Zuluaga DL, Janni M, Sanseverino W, Sonnante G. Transcriptomic response of durum wheat to nitrogen starvation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao G, Wen X, Yu L, Ji X. Identification of differentially expressed genes preferably related to drought response in pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) inoculated by arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (AMF) Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012;34:1711–1721. doi: 10.1007/s11738-012-0966-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyda M, Wąsek I, Tyrka M, Wędzony M, Szechyńska-Hebda M. Local and systemic regulation of PSII efficiency in triticale infected by the hemibiotrophic pathogen Microdochium nivale. Physiol. Plantarum. 2019;165:711–727. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joaquín-Ramos A, Huerta-Ocampo JÁ, Barrera-Pacheco A, De León-Rodríguez A, Baginsky S, de la Rosa APB. Comparative proteomic analysis of amaranth mesophyll and bundle sheath chloroplasts and their adaptation to salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:1423–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan S, Li Z, Li D, Yuan N, Hu Q, Luo H. Constitutive expression of rice microRNA528 alters plant development and enhances tolerance to salinity stress and nitrogen starvation in creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:576–593. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-Romdhane W, et al. Overexpression of AlTMP2 gene from the halophyte grass Aeluropus littoralis in transgenic tobacco enhances tolerance to different abiotic stresses by improving membrane stability and deregulating some stress-related genes. Protoplasma. 2018;255:1161–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00709-018-1223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashraf MFMR, Foolad MR. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007;59:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4350965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lushchak VI. Adaptive response to oxidative stress: Bacteria, fungi, plants and animals. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C. 2011;153:175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi K, et al. Reactive oxygen species-mediated cellular stress response and lipid accumulation in oleaginous microorganisms: The state of the art and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:793. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Møller IM, Sweetlove LJ. ROS signalling–specificity is required. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang S, et al. Peanut genes encoding tetrapyrrole biosynthetic enzymes, AhHEMA1 and AhFC1, alleviating the salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019;137:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali Y, Aslam Z, Ashraf MY, Tahir GR. Effect of salinity on chlorophyll concentration, leaf area, yield, and yield components of rice genotypes grown under saline environment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;1:221–225. doi: 10.1007/BF03325836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao GG, Rao GR. Pigment composition and chlorophyllase activity in pigeon pea (Cajanus indicus Spreng) and Gingelley (Sesamum indicum L.) under NaCl salinity. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1981;19:768–770. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno JC, Mi J, Agrawal S, Kössler S, Turečková V, Tarkowská D, Thiele W, Al-Babili S, Bock R, Schöttler MA. Expression of a carotenogenic gene allows faster biomass production by redesigning plant architecture and improving photosynthetic efficiency in tobacco. Plant J. 2020;103:1967–1984. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaiser WM, Stepper W, Urbach W. Photosynthesis of isolated chloroplasts and protoplasts under osmotic stress. Planta. 1981;151:375–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00393294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi R, Karan R, Singla-Pareek SL, Pareek A. Ectopic expression of Pokkali phosphoglycerate kinase-2 (OsPGK2-P) improves yield in tobacco plants under salinity stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:27–41. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1864-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Passricha N, Saifi SK, Kharb P, Tuteja N. Marker-free transgenic rice plant overexpressing pea LecRLK imparts salinity tolerance by inhibiting sodium accumulation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019;99:265–281. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao S, et al. Wheat microRNA member TaMIR444a is nitrogen deprivation-responsive and involves plant adaptation to the nitrogen-starvation stress. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016;34:931–946. doi: 10.1007/s11105-016-0973-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo J, Zhou J, Li H, Shi W, Polle A, Lu M, Sun X, Luo ZB. Global poplar root and leaf transcriptomes reveal links between growth and stress responses under nitrogen starvation and excess. Tree Physiol. 2015;35:1283–1302. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iqbal A, Dong Q, Wang X, Gui H, Zhang H, Zhang X, Song M. Transcriptome analysis reveals differences in key genes and pathways regulating carbon and nitrogen metabolism in cotton genotypes under n starvation and resupply. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1500. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xin W, Zhang L, Zhang W, Gao J, Yi J, Zhen X, Li Z, Zhao Y, Peng C, Zhao C. An integrated analysis of the rice transcriptome and metabolome reveals differential regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in response to nitrogen availability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2349. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tiwari V, Chaturvedi AK, Mishra A, Jha B. Introgression of the SbASR-1 gene cloned from a halophyte Salicornia brachiata enhances salinity and drought endurance in transgenic groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) and acts as a transcription factor. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0131567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mishra A, Jha B. Cloning differentially expressed salt induced cDNAs from Dunaliella salina under super saturated salt stress using subtractive hybridization. Bot. Mar. 2011;54:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horsch RB, Fry JE, Hofmann NL, Eichholtz D, Rogers SGR, Fraley T. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4691.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]