Abstract

Together with the ongoing serious COVID-19 second wave in India, a serious fungal infection, mucormycosis has been increasingly found in COVID-19-recovered patients. Colloquially known as ‘black fungus’, mucormycosis commonly causes necrosis in the head and neck including the nose, paranasal sinuses, orbits, and facial bones, with possible intracranial spread. The disease causes high morbidity and mortality given that it progresses rapidly and diagnosis is often delayed. Given the sheer magnitude of the outbreak, the Indian Health Ministry has advised all states to declare mucormycosis an epidemic. Typically, the disease has been found to be linked to COVID-19 infections caused by the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant, which has spread rapidly throughout the country. This variant has already become a cause for global concern, having spread to at least 40 countries, including the USA and UK. We present the findings of a study conducted on COVID-19 associated mucormycosis (CAM) patients, and discuss the associated risk factors to raise awareness for OMFS colleagues.

Keywords: COVID-19, B.1.617.2, SARS-CoV-2, Mucormycosis, Black fungus, Post-COVID Mucormycosis, COVID-19 associated mucormycosis, CAM, Second wave, India

Introduction

While India has not been able actively to control and limit the second wave of COVID-19,1 the number of new cases is now in decline.2 Despite this, emerging complications associated with COVID-19 are being reported, with the fungal infection mucormycosis becoming a serious issue in India due to its unprecedented surge and high morbidity.3, 4

Mucormycosis, colloquially known as ‘black fungus’ in India, is a fungal infection caused by the mucormycetes family of moulds, which are widespread decomposers of organic matter found in soil and dust. Mucormycetes is a fungus with at least 20 pathogenic species divided into 12 genera. Rhizopus is the genus that has been linked to most cases of mucormycosis in the literature.5

Mucormycosis occurs relatively commonly in patients with certain predisposing medical conditions such as immunosuppression and diabetic ketoacidosis.6 It infiltrates the vascular lamina, causing infarction and necrosis as well as inflammation.7 Progressive tissue necrosis can occur at different anatomical sites depending on how the fungal exposure has taken place, and can be through inhalation, ingestion, direct contact, or traumatic innoculation.6 It affects the head and neck, respiratory and central nervous systems, the gastrointestinal tract, and other areas. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis affects the head and neck, with the most common site being the nose, but the disease can spread to the paranasal sinuses, orbit, facial bones, and cranial cavity.8 Loose teeth, gingival abscess, and dental extraction are often the first symptoms that present to OMFS. Mucormycosis in the bone marrow may promote fungal growth by damaging the endothelial lining of vessels, resulting in vascular insufficiency and leading to bony necrosis and fungal osteomyelitis. This complication is more aggressive than the more common bacteria-associated osteomyelitis.8

The angioinvasive nature of mucormycosis, characterised by thrombosing vasculitis, and its role in host invasion have been attributed to increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFRB) signalling.9 Fatality rates for severe infections can be close to 100% despite various active treatments.6 When mucormycosis is suspected, adequate imaging to document the extent of the disease is strongly advised, followed by surgical debridement. The use of high-dose liposomal amphotericin B as a first-line treatment is strongly suggested, whereas intravenous isavuconazole and intravenous or delayed-release-tablet posaconazole have also been advocated.10

Following a sharp rise in the number COVID-19 patients infected with mucormycosis, the Indian Health Ministry has advised all States to declare mucormycosis itself an epidemic.3

Social media and press releases contain anecdotal and speculative reports about its cause. Various risk factors, such as the long-term use of steroids, antibiotic multivitamins, and zinc, have been linked to its incidence.11 Further, mucosal erosion secondary to the aggressive use of steam inhalation or the use of high-flow oxygen have also been considered as factors promoting fungus colonisation.11 Contamination from the use of industrial oxygen, low-quality oxygen cylinders, low-quality oxygen piping systems, and ordinary tap water in ventilators, are also being cited as causative factors.11, 12 Additionally, COVID-19 is known to cause hyperglycaemia in some patients, which could predispose to fungal infection.13

To further explore the risk factors, we studied the available data on COVID-19 associated mucormycosis (CAM) patients from the Bengaluru and Kalaburagi (Gulbarga) regions of India.

Methods

We obtained data from COVID-19 associated mucormycosis patients in India’s Bengaluru and Kalaburagi districts. Patients whose disease had not been established histopathologically were excluded from the study. We collected information such as age, gender, diabetes mellitus status, hypertension, existing immunocompromised conditions, time duration for reporting of diseases after COVID-19 treatment, vaccination history, use of oxygen and/or ventilator support, and steroid, multivitamin, and zinc medications. The data were tabulated and examined for the presence of any risk factors.

Results

Twenty-eight patients presented to OMFS, with a mean (SD) age of 49.1 (10.8) years. Twenty patients (71%) were aged between 41 and 60 years. Most were male (n = 22) and the major comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (n = 27, 96%) followed by hypertension (n = 8). Uncontrolled diabetes was found in 19 patients (68%). Only 13 (46%) had had steroid therapy, with four (14%) of these having been given steroids for more than 10 days. Oxygen was used in 17 patients (61%), but only one required ventilator support.

The interval between COVID-19 recovery and the first reporting of patients with mucormycosis was more than 15 days in 10 patients (36%), followed by 10 - 14 days in eight.

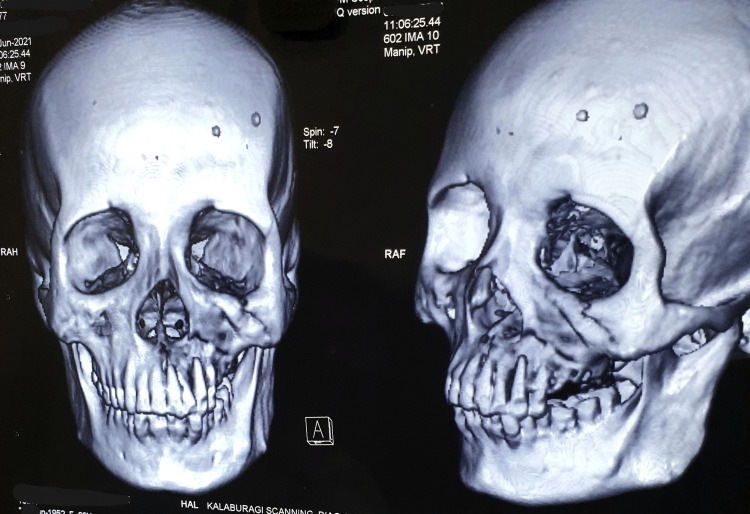

Only two patients had received COVID-19 vaccinations, half of those (n = 14) in our series presented with both mucormycosis pansinusitis and maxillary osteomyelitis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ), while another six (21%) presented with maxillary osteomyelitis that required functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) for necrotic tissue debridement.

Fig. 1.

CT scan imaging of COVID-19 associated mucormycosis-affected maxilla.

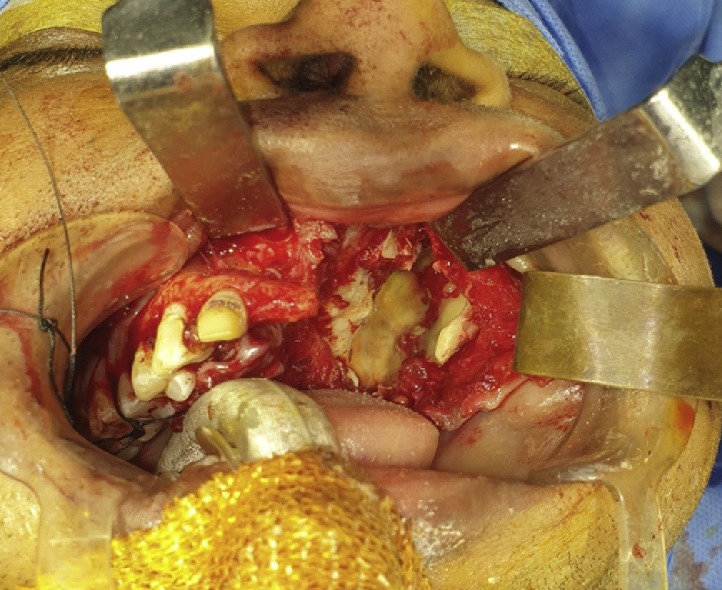

Fig. 2.

Osteomyelitis of maxilla secondary to COVID-19 associated mucormycosis.

Discussion

We have found that middle-aged COVID-19 patients who were treated with steroids for diabetes mellitus were prone to mucormycosis. The COVID-19 outbreak emphasises the need to understand the complex pathophysiology of diabetes and other diseases. Pathological changes in the pancreas were observed in patients with severe COVID-19, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 can cause pancreatic injury,13 and this could be one of the reasons why COVID-19 patients with no history of diabetes have high blood glucose levels.13, 14

The most common cause of drug-induced hyperglycaemia is steroids,15 which aggravate hyperglycaemia in patients with known diabetes mellitus (DM). Diabetes-related hyperglycaemia is thought to cause immune response dysfunction, resulting in an inability to control the spread of invading pathogens.16

Diabetes mellitus, when combined with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and steroid therapy, appears to cause a vicious cycle of hyperglycaemia and immunosuppression, which can lead to severe fungal colonisation such as mucormycosis.

Typically, the disease is seen during the COVID-19 recovery period, suggesting that multiple factors facilitate fungal colonisation. In most of the cases in our series, the time interval between COVID-19 and initial diagnosis of mucormycosis was 10 -15 days. Patients may have overlooked the symptoms of mucormycosis (especially pain), confusing it with the residual COVID-19 symptoms, and therefore presented late to the hospital. Furthermore, we observed that dental symptoms (Fig. 3 ) were not addressed at initial hospital visits, and priority was given to nasal or sinus symptoms with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) only. Patients eventually presented with advanced maxillary disease at a later follow-up stage (1-3 weeks). It is important to evaluate maxillary bone involvement on computed tomography (CT) at an early stage in an attempt to limit tissue necrosis. If both nasal and maxillary disease is found jointly, it is easier to operate on the maxilla first (Fig. 4 ), which provides better and additional endoscopic access for the clearance of nasal disease through the maxillary sinus.

Fig. 3.

Osteomyelitis of maxilla secondary to COVID-19 associted mucormycosis presenting as periodontal abscesses with oedematous gingivae.

Fig. 4.

Improved access for endoscopic intervention through maxillary sinus after debridement of necrotic maxillary bone.

Since only two patients in our series had been vaccinated, it confirms the vital role of the COVID-19 vaccine in reducing serious complications and comorbidities of the virus, including mucormycosis infections.

Conclusion

The second wave of COVID-19 in India has led to more deaths than the first,17 and in just a few weeks the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant became the dominant strain. It has since spread to about 40 nations, which include the United Kingdom, Fiji, and Singapore.18 The first case of Covid-19 related mucormycosis has now been found in Chile.19 It is important to recognise this infection at an early stage to potentially reduce soft and hard tissue necrosis and severe complications, and alert colleagues of this mutilating and life-threatening infection.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement/confirmation of patients’ permission

Ethics approval N/A. Patients’ permission obtained.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Sudhir Raikar, Pune and Ramesh Patil, Solapur for their essential assistance in performing the research and preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bhuyan A. Experts criticise India’s complacency over COVID-19. Lancet. 2021;397:1611–1612. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00993-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID-19 update. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. HFW/COVID States data/27th May 2021/1. Available from URL: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1722035 (last accessed 19 August 2021).

- 3.Additional 29,250 vials of Amphotericin-B allocated to States/UTs 19,420 vials of Amphotericin-B were allocated on 24th May. Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, India. Available from URL: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1721840 (last accessed 19 August 2021).

- 4.Szarpak L., Chirico F., Pruc M., et al. Mucormycosis — a serious threat in the COVID-19 pandemic? J Infect. 2021;83:237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes M.Z., Lewis R.E., Kontoyiannis D.P. Mucormycosis caused by unusual mucormycetes, non-Rhizopus, -Mucor, and -Lichtheimia species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:411–445. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy J., Harris J., Gade L., et al. Mucormycosis outbreak associated with hospital linens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:472–476. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravani S.A., Agrawal G.A., Leuva P.A., et al. Rise of the phoenix: mucormycosis in COVID-19 times. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1563–1568. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_310_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sai Krishna D., Raj H., Kurup P., et al. Maxillofacial infections in Covid-19 era-actuality or the unforeseen: 2 case reports. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;(May):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12070-021-02618-5. (online ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park Y.L., Cho S., Kim J.W. Mucormycosis originated total maxillary and cranial base osteonecrosis: a possible misdiagnosis to malignancy. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:65. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01411-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornely O.A., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Arenz D., et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:e405–e421. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients: what are the risk factors other than diabetes and steroid use? Times of India, last updated 31 May 2021. Available from URL: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/mucormycosis-black-fungus-in-covid-19-patients-what-are-the-risk-factors-other-than-diabetes-and-steroid-use/photostory/83083557.cms (last accessed 19 August 2021).

- 12.Mordani S. Dangerous cocktail of antibiotics, steroids, excessive steam leading to surge in black fungus cases? India Today, 24 May 2021. Available from URL: https://www.indiatoday.in/coronavirus-outbreak/story/mucormycosis-black-fungus-cases-india-antibiotics-steroids-excessive-steam-studies-1806068-2021-05-23 (last accessed 19 August 2021).

- 13.Montefusco L., Ben Nasr M., D’Addio F., et al. Acute and long-term disruption of glycometabolic control after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Metab. 2021;3:774–785. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00407-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J., Wu C., Wang X., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on blood glucose: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.574541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho A.E., Chapman K.E. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berbudi A., Rahmadika N., Tjahjadi A.I., et al. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:442–449. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191024085838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiyar Y., Chandru V., Chatterjee M., et al. India’s resurgence of COVID-19: urgent actions needed. Lancet. 2021;397:2232–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01202-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaidyanathan G. Coronavirus variants are spreading in India — what scientists know so far. Nature. 2021;593:321–322. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott L. Chile detects first case of Covid ‘black fungus’. The Times, 3 June 2021. Available from URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/chile-detects-first-case-of-covid-black-fungus-j87dkshb0 (last accessed 19 August 2021).