Summary

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death and a major contributor to disability worldwide. Currently, Korea is among countries with the lowest CVD mortality rates, and the age-adjusted CVD mortality rate is still decreasing. However, depending on the CVD type, the mortality and incidence trends vary. Without age-standardization, cerebrovascular disease mortality peaked in 1994 (82.1 per 100K) and continued to decline until 2018 (44.7 per 100K), while heart disease mortality recorded the lowest level in 2001 (44.9 per 100K) then increased again until 2018 (74.5 per 100K). Age-standardized mortality rates showed different trends: both cerebrovascular disease and heart disease mortality rates have declined over the past few decades, although the rate of decline varies. Based on the National Health Insurance claim database, the numbers of hospitalization for cerebrovascular disease and ischemic heart disease are increasing, but the age-standardized hospitalization rates are decreasing. Unlike other types of CVDs, heart failure is rapidly increasing in both mortality and hospitalization rates regardless of age-standardization. Seventy percent of Korean adults have at least one risk factor, 41% have ≥ 2 risk factors, and 19% have ≥ 3 risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and smoking. Exposure to multiple risk factors increases with age, with 65% of senior citizens over 70 having ≥ 2 risk factors and 34% having ≥ 3 risk factors. As the elderly population, especially those with multiple risk factors and chronic disorders, is increasing, the management of this high-risk group will be an important challenge to prevent CVD in Korea.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, risk factor, epidemiology, mortality, incidence, Korea

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death and a major contributor to disability worldwide (1). In high-income countries such as Europe, North America, and Australia, CVD mortality, mainly due to ischemic heart disease and stroke, has been decreasing since the late 20th century, and the trend of decline will continue although the rate of decline has been slowing recently. However, the prevalence of CVD will increase due to the prolonged survival of CVD patients, and the absolute number of CVD deaths will increase too because the population is aging. Assuming that the level of major cardiovascular risk factors remains unchanged, the number of middle-aged people suffering from heart disease or stroke will increase significantly in most countries, and a huge number of adults aged 35 to 64 will die of CVD over the next 30 years (1-3).

In South Korea (hereinafter referred to as Korea), the incidence and mortality rate of CVD have increased for decades, but the age-standardized mortality rate has recently begun to decline. However, the burden of CVD is still likely to increase. This review will look over the recent changes of CVD in Korea through descriptive epidemiologic measures such as mortality, incidence and prevalence, and predict the burden of CVD in the future through the distribution of major cardiovascular risk factors.

Deaths from CVD

An estimated 17.9 million of people died from CVDs in 2016 worldwide, representing 31% of all global deaths. Of these deaths, 85% are due to ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease (4). Recently, CVD mortality rates are decreasing in developed countries with high income levels, but the global number of CVD deaths is expected to continue to increase as CVD is rapidly increasing in low-income and middle-income countries (5). CVD is the leading cause of death in most parts of the world, but it is the second leading cause of death following cancer in some regions of East Asia including Taiwan, Singapore, Japan and Korea (Figure 1) (6).

Figure 1.

Leading causes of death in selected regions from the Global Burden of Disease Study. CVD, cardiovascular disease; TB, tuberculosis; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; NTDs, neglected tropical diseases. (Data source: http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/data-visualizations).

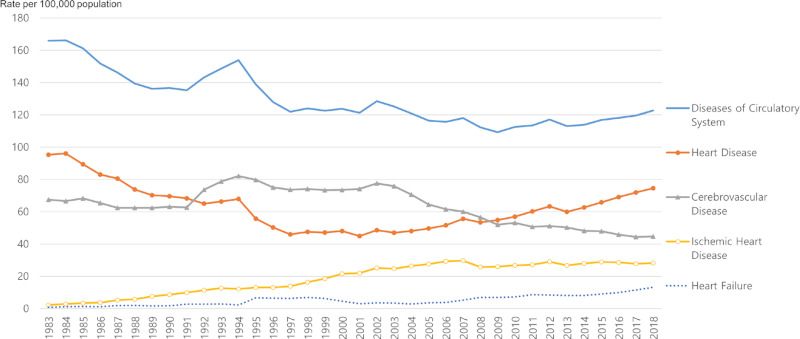

In Korea, CVD had been the most common cause of death until 1999, but thereafter cancer has been the number one cause of death and CVD has been the second one. Currently, Korea is among the countries showing the fastest decline in age-adjusted CVD mortality worldwide (7). Based on year 1983 to 2018 data on causes of death from the National Statistical Office, mortality from any circulatory system disease has decreased from 165.9 (per 100,000 population) in 1983 to 109.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2009, but increased again up to 122.7 (per 100,000 population) in 2018.

Fortunately, the death rate of cerebrovascular disease peaked at 82.1 (per 100,000 population) in 1994 and continued to decline to 44.7 (per 100,000 population) in 2018. The mortality rate from total heart diseases decreased from 95.3 (per 100,000 population) in 1983 to 44.9 (per 100,000 population) in 2001, but increased again to 74.5 (per 100,000 population) in 2018. The increase in total heart disease mortality in the early 2000s was mainly due to an increase in ischemic heart disease mortality, and the increase in the 2010s was largely due to an increase in heart failure mortality (Figure 2). The recent rapid increase in heart failure mortality in Korea is attributed to a surge in the elderly population, an increasing number of survivors after coronary artery disease, and an increase in heart failure diagnosis rates.

Figure 2.

Crude mortality from cardiovascular disease in Korea, 1983-2018. (Data Source: Causes of Death Statistics, Statistics Korea)

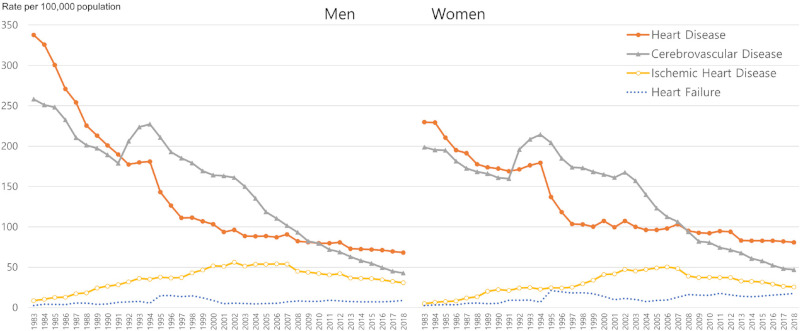

Figure 3 shows the age-standardized mortality from total heart diseases, ischemic heart disease, heart failure and cerebrovascular diseases in Korean men and women. Age-standardized rates were calculated using the direct method with the age structure of each male and female population in 2018. Over the past 36 years, the age-standardized mortality rate from total heart disease decreased a lot both in men and women. In the past, heart disease mortality rates were much higher in men than women, but have been reversed recently. The reason why heart disease mortality is higher in women is because the proportion of elderly people is much higher in women. When both men and women's heart disease mortality rates are standardized to the same population structure, the rate is still higher in men than in women (8). Age-standardized mortality rate from ischemic heart disease increased rapidly until the mid-2000s. In men, it peaked at 56.2 (per 100,000 population) in 2002, and in women at 50.4 (per 100,000 population) in 2006. However, it began to decline from that point to 2018, with a decrease of 45% for men and 49% for women. On the other hand, the age-standardized mortality from heart failure is increasing rapidly, which has led to a slowdown in the rate of decline in heart disease mortality. Heart failure mortality is increasing much faster in women because the proportion of elderly women is increasing faster.

Figure 3.

Age-standardized mortality from selected cardiovascular diseases in Korea, 1983-2018. (Data Source: Causes of Death Statistics, Statistics Korea)

For stroke (cerebrovascular disease), the crude mortality rate also decreased, but the age-standardized mortality rate decreased much faster. Between 1983 and 2018, the age-standardized stroke mortality decreased by 83% in men and 76% in women. Among the subtypes of stroke, there had been more deaths caused by hemorrhagic stroke (non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage and subclinical hemorrhage) until 2002, but there were more deaths caused by ischemic stroke since then. Both because of the decreasing incidence of stroke due to improved blood pressure control since the 1990s and the improving survival of patients with acute stroke might contribute to the rapid reduction of stroke mortality in Korea.

Incidence and prevalence of CVD

Unlike mortality data, national representative morbidity data are very limited, making it difficult to estimate the absolute level and time trends of the incidence and prevalence of CVD in Korea. Reviewing the published results of recent Korean studies (9-16), it is presumed that the prevalence of overall CVD is increasing, and the incidence rate will vary depending on the subtype of CVD. Recently, a growing number of studies try to estimate the disease burden of major CVDs using the National Health Insurance (NHI) claims data which covers all Korean residents (9-11,13,15-21). The estimated incidence and prevalence rates may vary from study to study, because of the differences in the working definition of CVD diagnosis or in the methods of identifying new-onset events (22,23). However, if we interpret them carefully, these data would be useful for understanding the magnitude and trends of CVD, because the NHI data include medical service uses of the entire Korean population (24,25).

Recent studies using NHI data report the incidence of acute myocardial infarction in the range of 50-70 cases per 100,000 person-years in men and 20-30 cases per 100,000 person-years in women (13,16,17,19,21). The crude incidence rate of acute myocardial infarction has been decreasing since peaking in 2006-2007, but it has recently returned to rise (13,16,17). However, the age-adjusted incidence of myocardial infarction is not increasing, and the crude incidence appears to be increasing due to the increasing number of elderly people. Although it is not as big as in other countries, regional and socioeconomic differences in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction are also observed in Korea (13,18). The age-standardized incidence of acute myocardial infarction has been reported to be higher in the southeastern region compared to other parts of Korea (13). A study based on the NHI claim data of the year 2005 estimated prevalence of coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction at 2.38% and 0.31% for men and 2.53% and 0.20% for women, respectively (18). Another study based on the NHI claim data, reported that the prevalence of acute myocardial infarction increased from 0.38% to 0.46% between the year 2007 and 2012 (11).

The incidence of cerebrovascular disease showed different trends by types of hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke. Hemorrhagic stroke was a major type of cerebrovascular disease before the 2000s, but the rate of hemorrhagic stroke has decreased rapidly and currently ischemic stroke accounts for about two-thirds of all strokes in Korea. Recent data suggest that age-standardized incidences of overall stroke, ischemic stroke, and hemorrhagic stroke are all decreasing in Korea (10,14,16,19). The prevalence of stroke in the adult population in Korea was reported to be 1-2%, and the prevalence rate is estimated to be increasing despite the decrease in the incidence of stroke (10,14,19).

Unlike other kinds of CVD, heart failure shows rapidly increasing trends all in mortality, incidence, and prevalence. These increasing trends are observed even after age standardization (9,20). Another characteristic that heart failure is different from other CVDs is that it occurs more in women than in men. Between the year 2002 and 2013, the prevalence of heart failure increased from 0.54% to 1.34% in men, and from 0.96% to 1.72% in women (20).

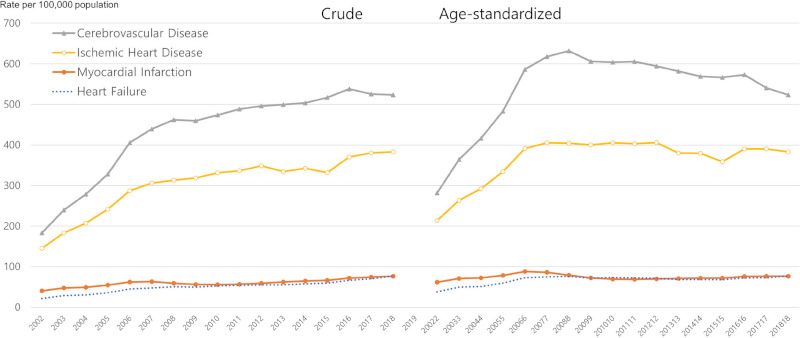

A very recent Korean study reported a much higher incidence and prevalence of CVDs, compared to other studies. In this study, the prevalence of total atherosclerotic CVD, ischemic stroke, and acute myocardial infarction were 10.11%, 1.86% and 0.56% in 2015, and the corresponding incidence rates were 6,994, 630 and 236 per 100,000 person-years, respectively (15). However, this study seems to have overestimated the rates because it used wider range of diagnosis codes compared with other studies, and it included any cases with CVD diagnosis codes regardless of primary or secondary diagnosis, and inpatient or outpatient clinics. Figure 4 shows the trends of hospitalization rate for cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure from 2002 to 2018, which were based on codes for primary admission diagnosis in the NHI claim database.

Figure 4.

Crude and age-standardized hospitalizations for selected cardiovascular diseases in Korea, 2002-2018. (Data Source: National Health Insurance Database)

Major risk factors of CVD

The change in incidence and dominant subtypes of CVD can be projected by the changes in cardiovascular risk factors (26), because a large portion of CVD risk is explained by the major modifiable risk factors such as high blood pressure, abnormal blood lipids, diabetes, overweight/obesity, and cigarette smoking (27,28). It is known that established risk factors such as high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking are major risk factors for CVD also in Korea (29) and other Asian populations (30). However, since the distribution of individual risk factors is changing, observing them will help predict changes in CVD incidence and subtype distribution in the near future (31). Among the major modifiable risk factors, cigarette smoking is a strong risk factor for most CVD subtypes, high blood pressure is more strongly related to cerebrovascular disease, especially hemorrhagic stroke, and hypercholesterolemia and diabetes are more closely related to ischemic heart disease (32-35).

We can observe the distribution of cardiovascular risk factors and their changes among Koreans, by reviewing the publications analyzing national representative datasets, such as the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), the National Health Screening Program, and the NHI claims (36,37).

The prevalence of obesity defined as a body mass index ≥ 25.0 kg/m2, according to the Asia-Pacific Region definition and the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO) guideline (38,39), was 35.7% among Korean adults aged 30 years or older in 2018. The prevalence of obesity is increasing in all ages, but in sex-specific analysis, the prevalence is increasing faster in men but the increasing trend is less significant in women. During the decade 2009-2018, the prevalence of obesity increased from 29.7% to 35.7% in the whole adult population, from 35.6% to 45.4% in male adults, and from 23.9% to 26.5% in female adults. Abdominal obesity shows a similar pattern. The prevalence of abdominal obesity, defined as a waist circumference of at least 90 cm in men and 85cm in women according to the KSSO criteria (38) was 23.8% in the total population, 28.1% in men, and 18.2% in women, recorded in 2018 (40,41).

The average level of blood pressure and the prevalence of hypertension of Korean adults have shown little change in the recent 10 years. Currently about 30% of Korean adults aged 30 or older have hypertension (12,31,42). However, according to the increase in the elderly population, the number of people with hypertension increased steadily, exceeding 11 million (42). Based on the NHI claims, the number of people diagnosed with hypertension increased from 3 million in 2002 to 8.9 million in 2016. The number of people using antihypertensive medication increased from 2.5 million in 2002 to 8.2 million in 2016. However, only 5.7 million people are persistently using antihypertensive medication (24,42). Based on the KNHANES data, hypertension awareness, treatment, and control rates increased fast until 2007, but showed a plateau thereafter (36,42). To achieve further improvement in hypertension management, it is important to increase awareness and treatment rates for younger people with hypertension, because awareness and treatment rates are below 50% among the young hypertensive patients aged less than 50 (43,44). It is another challenge to manage hypertension of elderly people who are increasing in absolute number and suffering from multiple chronic disorders (45).

The prevalence of diabetes among adults aged 30 years or older was 14.4%, when diabetes was defined as satisfying at least one aspect of physician diagnosis: current use of anti-diabetic medications, high fasting plasma glucose (FPG ≥ 126 mg/dL), or high hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c ≥ 6.5%) (46,47). Another 25.3% have an impaired fasting glucose level, defined as FPG of 100 to 125 mg/dL. The prevalence of diabetes was higher in men (15.8%) than in women (13.0%) and relatively higher among elderly people (29.8% in age 65 or older). However, the prevalence of diabetes became higher in women than in men (33.6% vs. 29.1%) after age 70. The prevalence of diabetes is increasing from 12.4% in 2011 to 14.4% in 2016, with a similar trend for men and women. The awareness and treatment rates of diabetes were 62.6% and 56.7%, respectively, but the control rate, defined by a HbA1c < 6.5%, was only 25.1% in 2016 (12,40,47).

In Korea, hyperlipidemia or dyslipidemia is on the rise overall, but it varies depending on its subtype and population characteristics (31,48,49). Based on the KNHANES, the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, defined as a total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL (50), among adults aged 30 or older has increased from 14.4% in 2012 to 19.9% in 2016 (40). When the dyslipidemia was defined as satisfying at least one of the following: elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dL), decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C < 40 mg/dL), hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 200 mg/dL), or current use of lipid-lowering medication, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was very high at 40.5% of the total, 47.9% in men and 34.3% in women. The elevated LDL-C was relatively high in women in their age 60s (39.9%) compared to men or women of other ages. Prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia was 17.5% of the total, being much higher for males than females (24.8% vs. 11.0%) (40). Triglyceride levels increased with age in women, but in men, it increased rapidly during younger adulthood, peaking at 50-54 years, and then decreased. Therefore, female seniors have higher triglyceride levels than men of the same age (48). Although the number of Korean adults taking lipid-lowering drugs is increasing rapidly, many of them do not use medication persistently, so it is necessary to increase compliance with drug treatment (40).

Cigarette smoking has long been the greatest cause of CVD and other non-communicable diseases. A Korean study reported that smoking contributed to 41% of coronary heart disease and 26% of strokes in Korean men (51). Korean data indicate that cigarette smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for type 2 diabetes: smoking is associated with diabetes incidence and mortality (52), and smoking cessation has been shown to reduce the risk of developing diabetes among smokers (53). The smoking rate for adult Korean males was very high at 79% in 1980, but fell to below 50% for the first time in 2007 (45.1%), and to less than 40% in 2015 (39.4%), and further decreased to 36.7% in 2018. Smoking rates in adult females were much lower than that in males, but it is increasing slowly but persistently (5.2% in 2001; 6.3% in 2010; 7.5% in 2018) (12). Reports have also indicated that smoking rates differ by age and socio-economic status. Lower household income was also associated with a higher smoking rate in both men and women, but this association was stronger in women. The smoking rate was 4% in women of the highest income quartile, but 11% in those of the lowest income quartile (31).

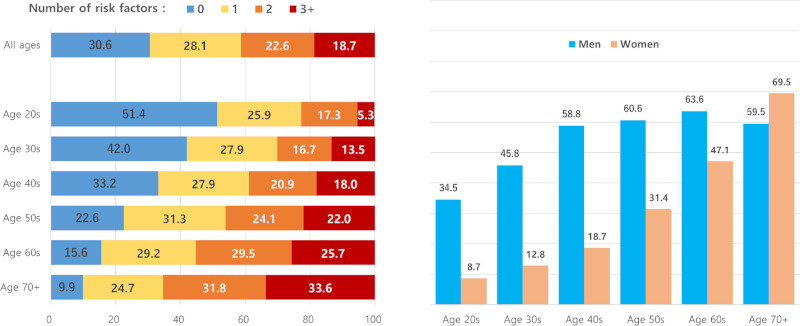

Since a person often has more than one risk factor, it is also necessary to evaluate multiple cardiovascular risk factors as well as individual risk factors. Figure 5 shows the combined prevalence of five major cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and smoking among Korean adults. Seventy percent of Korean adults (≥ 20 years old) have at least one risk factor, 41% have ≥ 2 risk factors, and 19% have ≥ 3 risk factors. Exposure to multiple risk factors increases with age, with 65% having ≥ 2 risk factors and 34% having ≥ 3 risk factors in those aged 70 years or older. Men and women show a different pattern in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. In men, exposure to multiple risk factors rapidly increases during the middle ages, but shows little change after their 60s. On the other hand, in women, exposure to multiple risk factors increase continuously during their life time. Thus women aged 70 years or older have more risk factors than men of the same age. As the elderly female population is rapidly increasing in Korea, it is a challenge to develop CVD prevention strategies targeted for elderly women with multiple risk factors.

Figure 5.

Distribution of number of cardiovascular risk factors by age and sex in Korean adults. Risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and cigarette smoking. (Data Source: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2018)

In summary, Korea has had the fastest decline in CVD mortality in the world, but the burden of CVD is still increasing due to the rapid aging of the population and the increasing number of patients with prevalent CVD, and this trend is expected to continue. Cerebrovascular disease is decreasing in both incidence and mortality rates. Ischemic heart disease is decreasing in mortality rates, but the decrease in incidence is not clear yet. Heart failure is quickly increasing both in incidence and mortality rates. Among cardiovascular risk factors, control of high blood pressure has improved a lot, but there is room for further improvement. Smoking rate is decreasing significantly but is still high in men, and it is increasing in women. Obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia are increasing, and measures are needed to reverse these trends. As the elderly population, especially those with multiple risk factors and chronic disorders, is increasing, the management of this high-risk group will be an important challenge to prevent CVD in Korea.

Funding: This work was supported under the framework of international cooperation program managed by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF- 2020K2A9A2A08000190).

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:2982-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011; 377:1438-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) Fact sheet. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed January 18, 2021).

- 5. Bovet P, Paccaud F. Cardiovascular disease and the changing face of global public health: A focus on low and middle income countries. Public Health Rev. http://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1007/BF03391643 (accessed December 11, 2011).

- 6. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD compare data visualization. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare (accessed March 25, 2021).

- 7. O'Rourke K, VanderZanden A, Shepard D, Leach-Kemon K. Cardiovascular disease worldwide, 1990-2013. JAMA. 2015; 314:1905. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baek J, Lee H, Lee H-H, Heo JE, Cho SMJ, Kim HC. Thirty-six year trends in mortality from diseases of circulatory system in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:320-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Youn JC, Han S, Ryu KH. Temporal trends of hospitalized patients with heart failure in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:16-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seo SR, Kim SY, Lee SY, Yoon TH, Park HG, Lee SE, Kim CW. The incidence of stroke by socioeconomic status, age, sex, and stroke subtype: A nationwide study in korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014; 47:104-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seo H, Yoon SJ, Yoon J, Kim D, Gong Y, Kim AR, Oh IH, Kim EJ, Lee YH. Recent trends in economic burden of acute myocardial infarction in South Korea. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0117446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Central Support Group for Cardiovascular Disease Control. 2020 Current Status and Issues of Chronic Diseases - Chronic Disease Fact Book. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Cheongju, Korea, 2020; pp. 51-96. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim RB, Kim HS, Kang DR, Choi JY, Choi NC, Hwang S, Hwang JY. The trend in incidence and case-fatality of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction patients in Korea, 2007 to 2016. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JY, Kang K, Kang J, et al. Executive summary of stroke statistics in Korea 2018: A report from the epidemiology research council of the Korean stroke society. J Stroke. 2019; 21:42-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim H, Kim S, Han S, Rane PP, Fox KM, Qian Y, Suh HS. Prevalence and incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Korea: A nationwide population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2019; 19:1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim RB, Kim BG, Kim YM, et al. Trends in the incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction and stroke in Korea, 2006-2010. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:16-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong JS, Kang HC, Lee SH, Kim J. Long-term trend in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction in Korea: 1997-2007. Korean Circ J. 2009; 39:467-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang HS, Kim HJ, Nam CM, Lim SJ, Jang YH, Kim S, Kang HY. The socioeconomic burden of coronary heart disease in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012; 45:291-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S, Lee H, Kim HS, Koh SB. Incidence, risk factors, and prediction of myocardial infarction and stroke in farmers: A Korean nationwide population-based study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020; 53:313-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee JH, Lim NK, Cho MC, Park HY. Epidemiology of heart failure in Korea: Present and future. Korean Circ J. 2016; 46:658-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim Y, Ahn Y, Cho MC, Kim CJ, Kim YJ, Jeong MH. Current status of acute myocardial infarction in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2019; 34:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimm H, Yun JE, Lee SH, Jang Y, Jee SH. Validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in Korean National Medical Health Insurance claims data: The Korean Heart Study. Korean Circ J. 2012; 42:10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yeom H, Kang DR, Cho SK, Lee SW, Shin DH, Kim HC. Admission route and use of invasive procedures during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction: analysis of 2007-2011 National Health Insurance database. Epidemiol Health. 2015; 37:e2015022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park JH, Kang HJ, Lee H, Do CH, Song JS, Bang JH, Ha S, Lee EJ, Shin AS. Data Resource Profile: The National health information database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:799-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi EK. Cardiovascular research using the Korean national health information database. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:754-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Joseph P, Leong D, McKee M, Anand SS, Schwalm JD, Teo K, Mente A, Yusuf S. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: The epidemiology and risk factors. Circ Res. 2017; 121:677-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016; 388:761-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yusuf PS, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004; 364:937-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jee SH, Appel LJ, Suh I, Whelton PK, Kim IS. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in South Korean adults: Results from the Korea Medical Insurance Corporation (KMIC) study. Ann Epidemiol. 1998; 8:14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters SAE, Wang X, Lam TH, Kim HC, Ho S, Ninomiya T, Knuiman M, Vaartjes I, Bots ML, Woodward M; Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Clustering of risk factors and the risk of incident cardiovascular disease in Asian and Caucasian populations: results from the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. BMJ Open. 2018; 8:e019335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim HC, Oh SM. Noncommunicable diseases: Current status of major modifiable risk factors in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013; 46:165-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990; 335:765-774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and stroke: 13,000 strokes in 450,000 people in 45 prospective cohorts. Prospective studies collaboration. Lancet. 1995; 346:1647-1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barzi F, Huxley R, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Ueshima H, Gu D, Kim HC, Woodward M. Association of smoking and smoking cessation with major causes of mortality in the Asia Pacific region: The Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Tob Control. 2008; 17:166-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Cholesterol, diabetes and major cardiovascular diseases in the Asia- Pacific region. Diabetologia. 2007; 50:2289-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seong SC, Kim YY, Park SK, Khang YH, Kim HC, Park JH, Kang HJ, Do CH, Song JS, Lee EJ, Ha S, Shin SA, Jeong SL. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e016640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seo MH, Lee WY, Kim SS, et al. 2018 Korean society for the study of obesity guideline for the management of obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019; 28:40-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004; 363:157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rhee EJ. Prevalence and current management of cardiovascular risk factors in Korean adults based on fact sheets. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2020; 35:85-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nam GE, Kim YH, Han K, Jung JH, Park YG, Lee KW, Rhee EJ, Son JW, Lee SS, Kwon HS, Lee WY, Yoo SJ. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2018: Data focusing on waist circumference and obesity-related comorbidities. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019; 28:236-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Korean Society Hypertension (KSH); Hypertension Epidemiology Research Working Group, Kim HC, Cho MC. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2018. Clin Hypertens. 2018; 24:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee H, Yano Y, Cho SMJ, Park JH, Park S, Lloyd-Jones DM, Kim HC. Cardiovascular risk of isolated systolic or diastolic hypertension in young adults. Circulation. 2020; 141:1778-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jeon YW, Kim HC. Factors associated with awareness, treatment, and control rate of hypertension among Korean young adults aged 30-49 years. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:1077-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee HY, Shin J, Kim GH, Park S, Ihm SH, Kim HC, Kim KI, Kim JH, Lee JH, Park JM, Pyun WB, Chae SC. 2018 Korean society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension: part II-diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2019; 25:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim MK, Ko SH, Kim BY, et al. 2019 Clinical practice guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2019; 43:398-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim BY, Won JC, Lee JH, Kim HS, Park JH, Ha KH, Won KC, Kim DJ, Park KS. Diabetes fact sheets in Korea, 2018: An appraisal of current status. Diabetes Metab J. 2019; 43:487-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park JH, Lee MH, Shim JS, Choi DP, Song BM, Lee SW, Choi H, Kim HC. Effects of age, sex, and menopausal status on blood cholesterol profile in the Korean population. Korean Circ J. 2015; 45:141-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim HC. Epidemiology of dyslipidemia in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2016; 59:352-357. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rhee E, Kim HC, Kim JH, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia. Korean J Intern Med. 2019; 34:723-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jee SH, Suh I, Kim IS, Appel LJ. Smoking and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in men with low levels of serum cholesterol: the Korea Medical Insurance Corporation study. JAMA. 1999; 282:2149-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jee SH, Foong AW, Hur NW, Samet JM. Smoking and risk for diabetes incidence and mortality in Korean men and women. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33:2567-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hur NW, Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Lee HC, Suh I. Smoking cessation and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Korea Medical Insurance Corporation study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007; 14:244-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]