Abstract

Patients have historically travelled from across the world to the United States for medical care that is not accessible locally or not available at the same perceived quality. The COVID‐19 pandemic has nearly frozen the cross‐border buying and selling of healthcare services, referred to as medical tourism. Future medical travel to the United States may also be deterred by the combination of an initially uncoordinated public health response to the pandemic, an overall troubled atmosphere arising from widely publicized racial tensions and pandemic‐related disruptions among medical services providers. American hospitals have shifted attention to domestic healthcare needs and risk mitigation to reduce and recover from financial losses. While both reforms to the US healthcare system under the Biden Presidency and expansion to the Affordable Care Act will influence inbound and outbound medical tourism for the country, new international competitors are also likely to have impacts on the medical tourism markets. In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, US‐based providers are forging new and innovative collaborations for delivering care to patients abroad that promise more efficient and higher quality of care which do not necessitate travel.

Keywords: academic medical centers, COVID‐19 pandemic, health policy, innovation, international patients, medical tourism, medical travel

1. INTRODUCTION

Pandemic‐imposed travel restrictions and the redirection of hospital resources to treat COVID‐19 patients have created both demand and supply side shocks around the world, freezing the cross‐border buying and selling of medical services referred to as “medical tourism.” The marketplace dynamics are further complicated in the United States by the recent change in administration and the country’s troubled atmosphere that has created an inhospitable environment for medical visitors from other countries. This COVID‐19 cocktail of confusion is transforming the landscape for US hospitals and clinics that serve international patients, as well as opening the door to new forms of competition.

2. MEDICAL TOURISM—CROSS BORDER TRADE IN MEDICAL SERVICES

The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) of the World Trade Organization deconstructs cross‐border trade in health services into four modes. 1 , 2 While medical tourism has historically focused on patients travelling out of their home country for medical care (Mode 2, Consumption Abroad) and hospitals establishing operations in another country (Mode 3, Commercial Presence), the COVID‐19 pandemic has been a tipping point for providers to develop more sophisticated telehealth strategies to reach patients abroad (Mode 1, Cross‐Border Supply of Services). This rapid shift to telehealth is leading to broader access to services, without patients needing to leave their home, and it is unlikely that the efficiencies and market access gained by the increased utilization of telehealth will be rolled back after travel restrictions are relaxed or eliminated. The commercial presence of hospitals abroad (Mode 3) will also be impacted in the near term. US companies, including academic medical centers (AMCs), have been establishing operations in foreign markets for many years. Bumrungrad Hospital in Thailand was established by a US‐based healthcare company in 1991 (Mode 3, Commercial Presence) and has developed a large global patient base over the last 30 years (Mode 2, Consumption Abroad), and other notable healthcare providers have been establishing a commercial presence in foreign destinations, including Spanish healthcare conglomerate QuironSalud establishing operations in South America and Moorfield’s Eye Hospital (United Kingdom) establishing a Middle East presence. With financial challenges due to the pandemic, American hospitals are likely to reassess their involvement in cross‐border trade as they shift attention to domestic healthcare needs and implement strategies to mitigate financial losses.

3. FACTORS DETERRING MEDICAL TOURISM

The plummet of international travel has had a dramatic impact on medical tourism. Globally, international travel decreased by 87%, comparing January 2021 to January 2020. 3 Total travel and tourism spending for inbound travel to the United States was down 79% relative to 2019 (Figure 1), with January 2021 inbound spending on passenger airfares only 10% of spending in January 2019. 4 The continued pattern of lockdown/release/lockdown/release is expected to continue until vaccines are widely distributed, and uncertainty in future travel restrictions will continue to deter foreign patients from planning cross‐border medical travel.

FIGURE 1.

US travel spending receipts (Inbound Visitors to US), 2000—January 2021, Source: National Travel and Tourism Office, 2021; https://travel.trade.gov/research/reports/recpay/index.asp

The domestic and international media have described the national public health response to the pandemic before Biden took office as a failure, although recent vaccination distribution has been more favorably reviewed. The variability in social distancing guidelines, mask requirements and other mitigation efforts among states and local communities has created confusion for residents and failed to stop the spread of the virus. The United States has the largest number of deaths due to COVID‐19 of any country in the world, with more than 550,00 deaths (as of 31 March 2021), followed by Brazil (313,866), Mexico (201,832) and India (126,121) and ranks 13th for deaths per 100,000 population. 5

The overall image of the United States may be a deterrence that healthcare providers must overcome to attract international patients to again travel to the country for medical care, although the impact of the pandemic may be temporary unless the negative effects are prolonged and affect the identity or culture of the country. 6 The violence and protests ignited George Floyd’s death, rising Anti‐Asian violence, gun violence, anti‐mask activities and violence against healthcare workers, anti‐immigration policies, restrictions against travel to the United States from some of our closest Allies 7 have presented the country as a less than welcoming destination.

3.1. Short term impact of COVID‐19 for US hospitals & clinics

Unlike other developed economies, medical services in the United States are considered the responsibility of private citizens, rather than a government obligation. Therefore, hospitals and clinics are considered, and see themselves as consumer‐based enterprises. The dramatic increase in the global burden of non‐communicable diseases (NCDs), coupled with increases in wealth among emerging economies create a robust and sophisticated market from which US providers attracted foreign patients seeking treatments. 8 Elective surgeries generated $147 billion in revenue for US hospitals in 2019, 9 and the short‐term halting of and subsequent restrictions on elective procedures has resulted in deep financial losses. In the early phase of COVID‐19, non‐COVID inpatient admissions were approximately 60% of pre‐pandemic levels, 10 and hospital losses were estimated in excess of $50 billion per month between March and May 2020. 11 These unprecedented financial challenges have strained the US healthcare system overall.

The pent‐up demand in the immediate post‐pandemic period (late 2021 through 2022) will create a surge, challenging hospitals’ capacities to provide timely access to care, although pre‐pandemic US hospital occupancy was 65.5%, suggesting that there will be physical inpatient capacity. 12 However, US hospitals are apt to focus on the domestic rather than international patient market. Since the prices for US medical procedures are the highest in the world, some price‐sensitive international patients seeking elective procedures may be attracted by lower cost options offered by hospitals or specialty clinics in other countries. Other patients may opt to forego services altogether or delay care. An estimated 40% of Americans may have delayed or avoided care due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, 13 suggesting that there may be a substantial number of people globally who have delayed care, exacerbating underlying health conditions. The short‐term impact is loss of global market share to US providers and opportunities for others.

3.2. Close to home

US hospitals and clinics will refocus on short‐term revenue sources domestically and away from international markets in response to international travel restrictions and mounting financial losses. Established international patient programs in US hospitals generate approximately $15.7 million in gross revenue less direct international program expenses on average, 14 which is less than 1% of $1192 billion spent on hospitals in the $3.8 trillion national healthcare expenditure. 15 The costs of international marketing and complexity of managing foreign consumers has increased dramatically with the onset of COVID‐19 as fewer patients are able to travel to the country. In response to these challenges, AMCs will re‐examine their foreign market strategies, 16 , 17 and those with significant investments in offshore locations will “hedge their bets” by lowering their exposure in those foreign operations and locations. AMCs that have established foreign beachheads may try to sell them, establish them as regional hubs, or reformulate them as license‐only agreements, and each of those strategies have implications for international patient flow to the United States.

4. COMPETITORS BECOME ALLIES

With a heightened focus on the domestic market in the post‐pandemic period as economic pressures mount, US hospitals may coordinate referrals and pool risks. For example, Hospital A specializes in musculoskeletal disorders, while Hospital B specializes in cardiovascular disease. Hospital A and B may exchange referrals to improve outcomes and efficiencies while reducing overhead, especially for expensive technology and hard‐to‐find specialty personnel. The two hospitals may then jointly contract with self‐funded employers to offer employees specific services at lower cost and better outcomes. These direct contracts already occur and augur major changes in healthcare insurance and risk management markets, which in turn will impact medical tourism. 18 , 19

5. HEALTHCARE INSURANCE AND MEDICAL TRAVEL

Many AMCs and other hospitals are consumers of and active market actors in the US healthcare insurance marketplace. As large‐scale employers in many places, AMCs are trying to manage the costs of health insurance and medical care of their employees. The recent unsuccessful, high profile collaboration among Amazon, JP Morgan Chase, and Berkshire‐Hathaway—“Haven”—is evidence of the ambitious attempts to rein in spending by US employers. In the immediate post‐pandemic period, AMC’s will become more heavily involved in risk, like insurance companies. Value‐based healthcare is an example of the efforts to engage healthcare providers to reduce costs and improve outcomes. As US hospitals become more risk‐sensitive the interest in riskier foreign patients may wane.

6. SELF‐INSURED EMPLOYERS

Historically, companies that manage their own health insurance plans (ERISA compliant, self‐insured plans) were considered reasonable targets for those trying to “sell” medical tourism (medical services imports), since self‐insured employers directly bear the cost of medical care for their employees and paying for employees obtain lower cost care abroad may be a strategy to reduce overall healthcare costs. While this has been modestly successful, this market has not scaled. As a result of supply disruptions resulting from COVID‐19 and more risk being shifted to hospitals due to direct contracting with employers, there will be a consolidation among benefits managers handling self‐insured plans. Simple bundles or packages for episodes of care will be more transparent and available to more small and mid‐sized employers. While the overall number of employer‐based self‐insured plans will increase, their focus will be on the competitive offers from nearby hospitals and clinics that offer lower cost, high quality medical care domestically. Here too, COVID‐19 shocks will have ripple effects on foreign markets.

7. THE POLITICAL UNKNOWNS

The 2020 Presidential and Senate elections had a profound impact on the US healthcare system. The political landscape has changed with a Democratic President, Joseph R. Biden, and a 50‐50 split in the Senate with a deciding vote cast by Vice President, Kamala Harris. Initial signs indicate that the harsh divide between the two political parties as well as in American society overall has not abated. While still in the early days of the Biden Presidency, it is clear that healthcare policy will be redirected to protect and expand the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) that had been under attack from the Republican‐controlled Senate. President Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan expands health care coverage and lowers premium costs by increasing subsidies for individuals purchasing insurance through the exchanges created by the ACA. These provisions of the American Rescue Plan are aimed at stemming the flood of uninsured Americans.

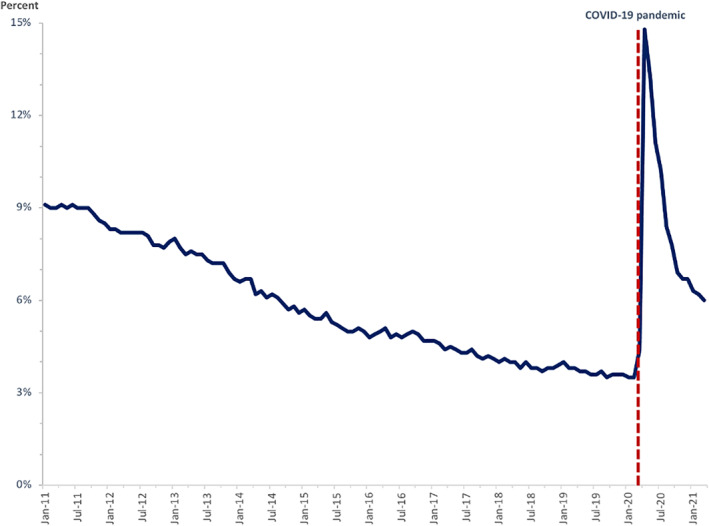

The number of uninsured Americans increased from 26.7 million in 2016 to 28.9 million in 2019—a 4‐year high—even before the pandemic hit the United States, 20 and is estimated at 31.5 million Americans in 2021. 21 The pandemic has had a substantial impact on unemployment (Figure 2), and many individuals who lost jobs are also at risk of losing health insurance coverage, although recent legislation made temporary coverage more affordable. 22 Average premiums and out‐of‐pocket costs have risen steadily, with the average premium for employer‐sponsored health insurance at $21,342 in 2020. 23 There are also hidden costs to uninsured individuals. Various studies estimate that between 20,000 and 35,000 Americans die each year due to lack of health insurance. 24 , 25

FIGURE 2.

US national unemployment rate, January 2011 to March 2021, Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021; https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

The impact of COVID‐19 continues to create havoc globally as borders open and close depending on spikes in the numbers of cases and the portion of the population that has been vaccinated. The initial responses to COVID‐19 in 2020 were slow and haphazard due to a lack of a coordinated national plan. Each state was and is still left to its own discretion as to the types of measures to take to reduce the risk of transmission, though the mortality rate is dropping. While deaths are decreasing, the total number of COVID cases is remaining steady or increasing as the spread of the disease progresses faster than the vaccine roll‐out.

Efforts to aggressively roll‐out vaccines to the US public are gathering steam but are hampered by vaccine hesitancy as well as widespread inequities within the society that are leaving out large swaths of the country. A recent study estimates that more than one‐third of Americans between 18 and 88 are vaccine hesitant for various reasons. 26 Vaccine hesitancy prevents herd immunity as experts estimate 60%–70% of the population must be vaccinated for herd immunity to take effect, although it may be impossible to reach in the near future. 27 Substantial logistical and behavioral challenges remain. 28 The SARS‐CoV‐2 coronavirus continues to mutate at a faster pace than vaccines can be administered around the world. The possibility of a new variant evolving to which vaccines are ineffective is a reality. 29 , 30 This proverbial sword of Damocles is hanging over the world, threatening to unleash new fury around the globe, putting healthcare systems under extreme stress again. Destinations that have done an excellent job containing the virus and reducing the risk of transmission through strong public policy measures, shutting borders, and aggressively vaccinating their populations are well‐positioned to continue combatting COVID‐19 and being prepared to face the next wave or new variant. Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, and South Korea are four examples.

Both Malaysia and South Korea are also medical travel destinations that have pivoted to telemedicine (Mode 1, Cross‐Border Supply of Services) and other services to maintain a foothold in the global market. South Korea has created a new guide for medical tourists going to the country during COVID‐19 to ease the pathways 31 and is utilizing digital health to expand access to Korean healthcare services. 32 Malaysia has adjusted its medical tourism strategy to include aggressive publicity and branding campaigns that showcase Malaysia’s healthcare quality and build confidence in Malaysia as a healthcare travel destination and facilitation of end‐to‐end infrastructure including digital adoption. 33 In January 2021, Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council, the organization responsible for promoting medical travel to the country, launched a partnership with DoctorOnCall to accelerate the adoption of telemedicine and other technologies. 34

A surprise contender for medical tourists is Israel. As of 6 February 2021, the country had fully vaccinated more than 80% of its adult population over the age of 60. The Abraham Accords peace agreement signed between Israel and the UAE ushers in a new dynamic in the Gulf. 35 Bahrain has signed a similar deal with Israel. 36 Travel between Israel and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries is likely to increase, including travel to Israel for medical care.

8. NEW INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION

Once borders open and international travel re‐emerges as a viable option for medical tourism, patients will begin to travel again. Pent‐up demand for dental services, for example, will most likely cause a surge of traffic at the US‐Mexico border as patients seek treatment as soon as it is seen to be safe. While some medical tourists have continued to cross the borders into other countries during periods when borders opened or venturing into other countries despite travel warnings, the numbers have been modest compared to pre‐pandemic numbers. 37

Competition by existing providers as well as new entrants into the market is already taking place for the high dollar value, low volume complex medical services like specialized surgeries and cancer treatments, which had been sought by foreign patients in the United States before COVID‐19. Healthcare providers in South Korea, Singapore and Malaysia among others, are actively attempting to serve complex patients with urgent medical needs who cannot or do not want to travel to the United States. This market shift is supported by the foreign governments in these countries, which are actively promoting their countries as destinations for foreign patents, unlike the United States government which takes no active role in abetting US hospitals’ competitive position abroad. 38 Once new pathways are established or existing pathways of care are re‐established, it will be difficult to shift those patterns of travel and trust.

The US healthcare system experienced a similar shock post 9/11 when visitors from the GCC Region were prevented from entering the country or felt unwelcome because of the post‐event anti‐Muslim sentiment portrayed widely in the media. Some of these patients went to other destinations like Germany, and the region invested heavily in its own healthcare infrastructure. International patient travel was slow to recover, but did rebound over the past 19 years, despite a global recession impacting both the United States and many countries that had residents seeking care abroad. The GCC Region is investing in healthcare workforce and infrastructure, 39 , 40 , 41 and consultants report an estimated 161 healthcare projects were underway at the end of 2020, with a combined value of $53.2 billion and will add more than 40,000 beds to the current capacity. 42 Furthermore, GCC countries continue to promote the region as a hub for medical tourism as part of their economic diversification plans.

9. LOOKING AROUND THE CORNER

As the world continues to struggle with the pandemic and many countries again implement measures to restrict movement within and across borders, the COVID‐19 pandemic is compelling new ways of delivering healthcare services, leaving behind many of the traditional models. For the foreseeable future, borders will continue to open‐close‐open‐close, discouraging people from making international travel plans. In the short term, US hospitals will look to specialization, improved services for their domestic markets, aggressive pricing and innovative offers to insurance companies and self‐insured employers to survive the pandemic–before rebuilding international patient services to pre‐COVID‐19 levels. The future of international patient services across the globe will integrate and expand telemediated service delivery, particularly at the diagnostic and rehabilitation phases of the care continuum for patients who will travel. New cross‐border relationships and collaborations are already being created to share knowledge and expertise, especially in the remote delivery of healthcare services. Robotic surgery, for example, reduces the need for surgeons to travel, opening the possibility for delivery of care beyond national borders. Clinical trials among international partners will improve personalized medicine by diversifying pooled genomic information to combat disease. 43

Changes in cross‐border exchange in health services in response to the pandemic may create opportunities for emerging economies, such as Russia, China, India and Brazil, which may recover more quickly than developed economies, to further develop their medical tourism markets. 44 , 45 Like other times in history, change has emerged from times of crisis. International patient travel will return at some point in the future. As a short‐term solution, providers are forging new and innovative collaborations for delivering care to patients abroad that do not necessitate travel.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Irving Stackpole is the President of Stackpole & Associates, which provides consultation related to medical tourism. Elizabeth Ziemba is President and Founder of Medical Tourism Training, which provides training and consultation related to medical tourism. Tricia Johnson is provides consultation to the US Cooperative for International Patient Programs, a non‐profit association of international patient programs of US hospitals.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published and not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The paper reflects the authors’ own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner. The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co‐authors and co‐researchers. The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research. All sources used are properly disclosed (correct citation). All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper, and will take public responsibility for its content.

Stackpole I, Ziemba E, Johnson T. Looking around the corner: COVID‐19 shocks and market dynamics in US medical tourism. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2021;36(5):1407‐1416. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3259

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data used in the figure are publicly available.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mutchnick l, Stern DT, Moyer CA. Trading health services across borders: GATS, markets, and caveats. Health Aff. 2005(Suppl). Web Exclusives:W5‐42‐W5‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Trade Organization . GATS: General Agreement on Trade in Services, Annex 1B. 1994:283‐317 1869 U.N.T.S. 183(33 I.L.M. 1167). www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/26‐gats.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNWTO . Tourist arrivals down 87% in January 2021 as UNWTO calls for stronger coordination to restart tourism. UN World Tourism Organization. 2021. https://www.unwto.org/news/tourist‐arrivals‐down‐87‐in‐january‐2021‐as‐unwto‐calls‐for‐stronger‐coordination‐to‐restart‐tourism. Published March 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Travel and Tourism Office . International visitation and spending in the United States, monthly spending (exports/imports), through January 2021. International Visitation and Spending in the United States. 2021. https://travel.trade.gov/outreachpages/inbound.general_information.inbound_overview.asp. Updated April 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine . Mortality analyses: Mortality in the most affected countries. 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality. Updated November 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bloom Consulting . COVID‐19 the impact on nation brands. Bloom Consulting & D2 Analytics; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Travelers prohibited from entry into the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/travelers/from‐other‐countries.html. Accessed April 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jakovljevic M, Jakab M, Gerdtham U, et al. Comparative financing analysis and political economy of noncommunicable diseases. J Med Econ. 2019;22(8):722‐727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Best MJ, McFarland EG, Anderson GF, Srikumaran U. The likely economic impact of fewer elective surgical procedures on US hospitals during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Surgery. 2020;168:962‐967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heist T, Schwartz K, Butler S. Trends in overall and on‐COVID‐19 hospital admissions, Issue Brief. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. https://www.kff.org/health‐costs/issue‐brief/trends‐in‐overall‐and‐non‐covid‐19‐hospital‐admissions/#:∼:text=The%20decrease%20in%20hospital%20admissions,the%20end%20of%20the%20month [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Hospital Association . Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial challenges due to COVID‐19. 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha‐covid19‐financial‐impact‐0520‐FINAL.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. In Table 89. Hospitals, beds, and occupancy rates, by type of ownership and size of hospital: United States, selected years 1975–2015. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KE, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID‐19‐related concerns—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(1250‐57). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel I, Johnson TJ, Garman AN, et al. The return on investment from international patient programs in American hospitals. Int J Pharm Healthc Mark. 2019;13:171‐182. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . CMS office of the actuary releases 2019 national health expenditures. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press‐releases/cms‐office‐actuary‐releases‐2019‐national‐health‐expenditures. Accessed April 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McHugh RM, Johnson TJ, Garman AN, Hohmann SF. Global healthcare business development: the case of non‐patient collaborations abroad for U.S. hospitals. Int J Healthc Manag. 2017;12(10):1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merritt MG, Jr , Railey CJ, Levin SA, Crone RK. Involvement abroad of U.S. academic health centers and major teaching hospitals: the developing landscape. Acad Med. 2008;83(6):541‐549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Direct contracting model options. 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation‐models/direct‐contracting‐model‐options. Accessed May 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miller S. Direct contracting with health providers can lower costs. 2018. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr‐topics/benefits/pages/direct‐contracting‐with‐health‐providers‐can‐lower‐costs.aspx. Accessed November 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tolbert J, Orgera K, Damico A. Key facts about the uninsured population. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Congressional Budget Office . Federal subsidies for health insurance coverage for people under age 65: 2020 to 2030; 2020:56571. [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Department of Labor . FAQs about COBRA premium assistance under the American Rescue Plan act of 2021; 2021. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about‐ebsa/our‐activities/resource‐center/faqs/cobra‐premium‐assistance‐under‐arp.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Claxton G, Rae M, Damico A, Young G, McDermott D, Whitmore H. Employer health benefits, 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanne JH. More than 26,000 Americans die each year because of lack of health insurance. BMJ. 2008;336(7649):855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU. Health insurance and mortality in US adults. Am J Publ Health. 2009;99(12):2289‐2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raja AS, Niforatos JD, Anaya N, Graterol J, Rodriguez RM. Vaccine hesitancy and reasons for refusing the COVID‐19 vaccination among the U.S. public: cross‐sectional survey. Health. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aschwanden C. Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature. 2021;591(7851):520‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosenbaum L. Escaping catch‐22—overcoming COVID vaccine hesitancy. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1367‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahase E. Covid‐19: What new variants are emerging and how are they being investigated? BMJ. 2021;372:n158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Callaway E. Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out. Nature. 2021;589:177‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. New rules for inbound medical tourism to South Korea. LaingBuisson. 2020. https://www.laingbuissonnews.com/imtj/news‐imtj/new‐rules‐for‐inbound‐medical‐tourism‐to‐south‐korea/. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Korea's Ministry of Health and Welfare and KHIDI announce Medical Korea . Global healthcare, where your days begin again. Business Wire; 2021. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chow P. Ready for revival. TTG Asia. 2021. https://www.ttgasia.com/2021/02/01/ready‐for‐revival/. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yun TZ. Digital healthcare: How telemedicine can transform—and save—medical tourism. The Edge Markets. 2021. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/digital‐healthcare‐how‐telemedicine‐can‐transform‐%E2%80%93‐and‐save‐%E2%80%93‐medical‐tourism. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cook SA. What's behind the new Israel‐UAE peace deal? Council on Foreign Relations. 2020. https://www.cfr.org/in‐brief/whats‐behind‐new‐israel‐uae‐peace‐deal. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Phillips J. How the Israel‐Bahrain peace deal will reshape the Middle East. The Heritage Foundation. 2020. https://www.heritage.org/middle‐east/commentary/how‐the‐israel‐bahrain‐peace‐deal‐will‐reshape‐the‐middle‐east. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeginsu C. Why medical tourism is drawing patient, even in a pandemic. New York Times; 2021. Accessed April 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tatum M. Will medical tourism survive COVID‐19? BMJ. 2020;370:m2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sheikh JI, Cheema S, Chaabna K, Lowenfels AB, Mamtani R. Capacity building in health care professions within the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: paving the way forward. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nashat N, Hadjij R, Al Dabbagh AM, et al. Primary care healthcare policy implementation in the eastern Mediterranean region; experiences of six countries: part II. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020;26(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khoja T, Rawaf S, Qidwai W, Rawaf D, Nanji K, Hamad A. Health care in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus. 2017;9(8):e1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bridge S. How coronavirus is reshaping the Gulf's healthcare investment landscape. Arabian Business. 2020. https://www.arabianbusiness.com/454491‐the‐changing‐face‐of‐the‐gccs‐healthcare‐investment‐landscape. Accessed April 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Popejoy AB. Diversity in precision medicine and pharmacogenetics: ethodological and conceptual considerations for broadening participation. Pers Med. 2019;12:257‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jakovljevic M, Timofeyev Y, Ranabhat CL, et al. Real GDP growth rates and healthcare spending—comparison between the G7 and the EM7 countries. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Daykhes AN, Jakovljevic M, Reshetnikov VA, Kozlov VV. Promises and hurdles of medical tourism development in the Russian Federation. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the figure are publicly available.