The rollout of a vaccination programme against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has been one of the biggest steps towards controlling the global COVID‐19 pandemic, with four new vaccines currently authorised for use by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Since February 2021, a preliminary report of cases of unusual thrombosis in the setting of concomitant thrombocytopenia following vaccination has emerged. 1 The authors describe nine patients in Germany and Austria who presented with clinical and serological features which mimic heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and the name vaccine‐induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT) was initially proposed. 1 The term vaccine induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) has since been also commonly used, with the condition being referred to as thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) by the CDC and FDA. Patients presented with symptomatic thrombosis, primarily cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (CSVT), and were predominantly young females. The EMA's Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) noted disproportionality for rare events such as disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), CSVT and haemorrhagic stroke, especially in younger patients aged 18–54. 2 They have since acknowledged a causal association between AZD1222 (COVID‐19 Vaccine AstraZeneca) and acquired coagulopathy as of 7 April 2021.

We describe the first reported Irish case of VITT. A 35‐year‐old Caucasian woman presented 14 days after vaccination with AZD1222. She presented with a medical history of migraine, with no known risk factors for thrombosis.

Following vaccination, she described general myalgia and extreme fatigue, and noticed the onset of bruising and petechiae 10 days later. She attended the Emergency Department 14 days following vaccination. Her petechiae had resolved but she had persistent bruising. She described a headache which was slightly different to her known migraine headaches. She had no recent exposure to heparin.

Laboratory investigation revealed thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 50 × 109/l, with a normal haemoglobin and white cell count. A coagulation screen showed a mildly prolonged PT and APTT at 12·7 s (normal: 9·6–11·8 s) and 31·3 s (normal 20·8–30·8 s), respectively. Fibrinogen was reduced at 1·16 g/l (normal 1·5–4 g/l) and the D‐dimer was markedly elevated at 9·83 μg/ml (normal < 0·42 μg/ml). Examination of the peripheral blood smear showed no red cell fragmentation, no blasts and some atypical lymphocytes. A MR cerebral venogram was carried out which excluded underlying CSVT. Marrow aspirate revealed some reactive features with no evidence of an underlying infiltrative disorder.

Given the temporal proximity to vaccination, the newly described VITT was suspected. 1 Somewhat atypically, an initial HIT screen using the particle gel immunoassay (PaGIA) was negative. The anti‐PF4 ELISA assay, using an Optivue analyser, was strongly positive with an optical density of > 2, indicating the presence of an antibody to platelet factor 4 (PF4). However, the heparin‐induced platelet aggregation (HIPA) study as well as the modified platelet aggregation study were negative, suggesting the absence of platelet activation in vitro.

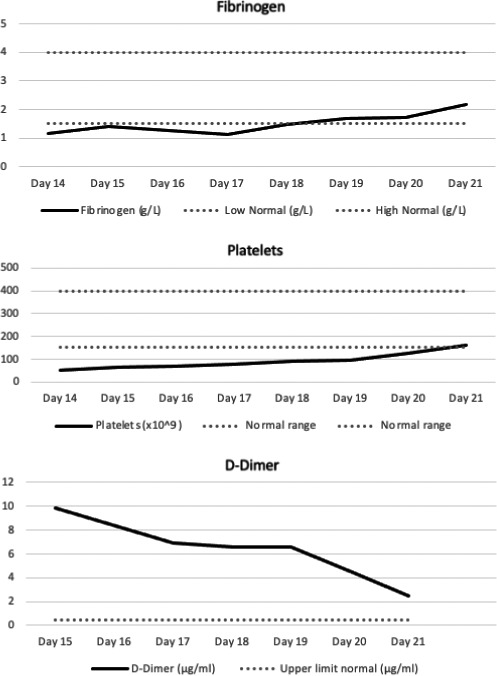

Given the emerging reports of CSVT, the patient was anticoagulated preemptively with apixaban. Her thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenaemia gradually improved over the following week and had normalised by day 21 post‐vaccination. Her D‐dimer level returned to normal, and she was discharged from the hospital (see Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Fibrinogen trend versus number of days post‐vaccination; platelet trend versus number of days post‐vaccination; D‐dimer trend versus number of days post‐vaccination. Bold continuous line: patient results. Area between dotted grey lines: normal range.

Our patient's case strongly mirrors those recently described in Northern Europe. Greinacher et al. described nine patients presenting over a period of a month with thrombosis at unusual sites in the setting of concomitant thrombocytopenia. Patients presented between 4–16 days following vaccination. Four patients underwent serological testing for platelet‐activating antibodies against PF4/heparin and showed strong activation, either in the presence of PF4 or AZD1222 vaccine. One serum sample showed platelet activation in the presence of heparin. 1

As VITT appears to be a markedly prothrombotic state, despite the absence of demonstrable thrombus in our patient, we commenced empiric anticoagulation in a similar fashion to optimal management of HIT. 3 We commenced Factor Xa inhibition using apixaban, avoiding heparin, given the similar pathogenesis of VITT to HIT and the previously documented case of in‐vitro cross‐over activation with heparin as outlined above. Due to the paucity of data available, the optimal duration of anticoagulation is unclear, but we plan to continue anticoagulation for four weeks in a similar fashion to standard management of HIT without thrombosis.

This case differs slightly to those previously reported by Greinacher et al., as our patient presented primarily with symptomatic thrombocytopenia and evidence of coagulation activation and fibrinolysis in the absence of thrombosis. The clinical course highlights the importance of early recognition of this syndrome and the potential benefit of early instigation of nonheparin‐based anticoagulation to avoid the development of serious thrombotic sequelae. The fact that the ELISA for heparin‐PF4 IgG antibody was positive in the absence of demonstrable platelet activation in vitro, with a negative HIPA assay, was surprising but could potentially explain why our patient did not have a thrombotic event.

The small cohort of patients previously described show a significant young female preponderance, as was the case with our patient. Though unclear as to whether it is due to genetic, hormonal or environmental factors, antibody responses to viral and bacterial vaccines are stronger in females than in males. 4 For example, dose response studies in humans receiving inactivated influenza vaccine found that female subjects achieved antibody titres equal to that of their male counterparts when vaccinated with half the dose. 5

Thrombotic and thrombocytopenic events appear to be associated with the AZD1222 vaccine and have not yet been described with COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines. Adenoviral vectors have been linked with thrombotic and thrombocytopenic events in pre‐clinical trials involving nonhuman primate and rabbit models. 6 , 7 Considering the homology which adenoviral vectors share with the replication‐incompetent simian adenoviral vector ChAdOx1 8 used in AZD1222, the ChAdOx vector may be implicated in the VITT pathogenesis. Furthermore, the AZD1222 vaccine employs a tissue plasminogen activator leader sequence to enhance immunogenicity. 9 Such a sequence could, theoretically, negatively impact the fibrinolytic system with fibrinolysis, leading to a marked increase in D‐dimers and hypofibrinogenaemia. Further expert discussions, data collection, monitoring and research are required to fully elucidate the relationship between the AZD1222 vaccine and VITT.

VITT is a rare, but potentially life‐altering, complication of AZD1222 vaccination. However, in an era of a worldwide public health emergency, with vaccination being a vital pathway to controlling the spread of disease, we will need to continue considering unique aspects of our biology and immune responses regarding gender differences, in predicting those most at risk of adverse events.

Author contributions

ER wrote the manuscript. DB and IMcD contributed toward writing the manuscript and provided critical feedback. AB aided in data collection and provided critical feedback. JMcH and KR interpreted data and provided critical feedback. HE oversaw data interpretation, writing and revision of the manuscript. All the co‐authors contributed to data collection and critically revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle P, Eichinger S. A prothrombotic thrombocytopenic disorder resembling heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia following coronavirus‐19 vaccination. research square. Published online 28 March 2021. [Cited 2021 April 5]. Available at: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs‐362354/v1

- 2. Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC), European Medicines Agency . Signal assessment report on embolic and thrombotic events (SMQ) with COVID‐19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1‐S [recombinant]) – COVID‐19 Vaccine AstraZeneca (Other viral vaccines). Cited 24th March 2021. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/prac‐recommendation/signal‐assessment‐report‐embolic‐thrombotic‐events‐smq‐covid‐19‐vaccine‐chadox1‐s‐recombinant‐covid_en.pdf

- 3. Watson H, Davidson S, Keeling D; Haemostasis and Thrombosis Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology . Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia: second edition. Br J Haematol. 2012; 159(5): 528‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engler RJ, Nelson MR, Klote MM, VanRaden MJ, Huang CY, Cox NJ, et al. Half‐ vs full‐dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (2004–2005): age, dose, and sex effects on immune responses. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(22):2405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolins N, Lozier J, Eggerman TL, Jones E, Aguilar‐Córdova E, Vostal JG. Intravenous administration of replication‐ incompetent adenovirus to rhesus monkeys induces thrombocytopenia by increasing in vivo platelet clearance. Br J Haematol. 2003;123(5):903–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cichon G, Schmidt HH, Benhidjeb T, Löser P, Ziemer S, Haas R, et al. Intravenous administration of recombinant adenoviruses causes thrombocytopenia, anemia and erythroblastosis in rabbits. J Gene Med. 1999;1(5):360–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dicks MDJ, Spencer AJ, Edwards NJ, Wadell G, Bojang K, Gilbert SC, et al. A novel chimpanzee adenovirus vector with low human seroprevalence: improved systems for vector derivation and comparative immunogenicity. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kou Y, Xu Y, Zhao Z, Liu J, Wu Y, You Q, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) signal sequence enhances immunogenicity of MVA‐based vaccine against tuberculosis. Immunol Lett. 2017;190:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]