Abstract

Background.

Professionalism has been given different definitions over time. These are, commonly theoretical and difficult to operationalize.

Purpose.

This study aimed to provide an operational definition of the concept of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Method.

Based on a concept analysis design, a meta-narrative review was conducted to extract information from 30 occupational therapy manuscripts.

Findings.

Professionalism is a complex competence defined by the manifestation of distinct attitudes and behaviours that support excellence in the occupational therapy practice. In addition, professionalism is forged and evolves according to personal and environmental characteristics. The manifestation of professionalism can lead to positive consequences for occupational therapists, clients, and the discipline, notably contributing to a positive and strong professional identity. Moreover, professionalism is also subject to cultural influences, which leads to variations in its development, manifestations, and consequences.

Implications.

This study offers a contemporary operational definition of professionalism and levers to promote its development and maintenance.

Keywords: Professional attitudes, Professional behaviours, Professional identity, Professional reasoning, Professional values

Keywords: Attitudes professionnelles, comportements professionnels, identité professionnelle, raisonnement professionnel, valeurs professionnelles

Abstract

Contexte de recherche.

Le professionnalisme a fait l’objet de différentes définitions au fil du temps. Ces définitions ont souvent été théoriques et difficiles à opérationnaliser.

Objectif.

Cette étude visait à fournir une définition opérationnelle du concept du professionnalisme en ergothérapie.

Méthodologie.

Selon un devis d'analyse de concept, une recension métanarrative des écrits scientifiques a été réalisée afin d’extraire les informations pertinentes de 30 manuscrits.

Résultats.

Le professionnalisme est une compétence complexe, définie par la manifestation d’attitudes et de comportements qui favorisent l’excellence dans la pratique de l’ergothérapie. De plus, le professionnalisme se forge et évolue selon des caractéristiques personnelles et environnementales. La manifestation de professionnalisme peut avoir des conséquences positives pour les ergothérapeutes, les clients et la discipline, en contribuant notamment à l’acquisition d’une identité professionnelle positive et forte. Le professionnalisme est également sujet à des influences culturelles, ce qui entraîne des variations dans son développement, ses manifestations et ses conséquences.

Implications.

Cette étude fournit une définition opérationnelle contemporaine du professionnalisme et des leviers qui permettent de favoriser son développement et son maintien.

Background

Professionalism is a key topic for many professionals, including occupational therapists. A Canadian survey suggested that more than 88% of occupational therapists find professionalism to be “very important” for their practice (Drolet & Désormeaux-Moreau, 2014). This concern is also shared by authors in the allied health literature, who proposed that professionalism is an essential component of a value-based practice, which is a complement to an evidence-based practice (Fulford, 2004). The combination of these two types of practice supports professionals’ decision-making processes in complex situations, thereby contributing to a fair professional practice. Occupational therapists must generally make complex decisions and are expected to have a fair practice. Hence, focusing on the key components of professionalism is crucial. Occupational therapy associations and guidelines suggest the importance of developing professionalism amongst students and supporting the continuous development of professionalism during an individual’s career. However, published documents lack a definition of what professionalism means and how to develop it (Reiter et al., 2018). This is in line with other works suggesting that professionalism is commonly assumed rather than clearly explained (Bryden et al., 2010; van Mook et al., 2009). This article presents a concept analysis research aiming to provide an operational definition of the concept of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Dictionaries propose several definitions of professionalism. For instance, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines professionalism as “the conduct, aims, or qualities that characterize or mark a profession or a professional person” (Merriam-Webster, 2019; online). For the Cambridge Dictionary, professionalism is “the combination of all the qualities that are connected with trained and skilled people” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2019; on line). These definitions are generic, somewhat circular, poorly informative for health professionals, and difficult to operationalize in the context of occupational therapists.

To improve the rigour of the definitions, some authors suggested the need for a profession-specific understanding of professionalism (Aguilar et al., 2012; Bryden et al., 2010). In fact, a review of the medical and allied health literature indicated that professionalism relies on the application of the values of the profession and the demonstration of professional behaviours and attitudes (Aguilar et al., 2011). These values, behaviours, and attitudes may differ between professions, leading to different conceptualizations of professionalism. For instance, in the field of nursing, professionalism is defined as having six components: (a) acting in the patients’ interests, (b) having high standards of competence and knowledge, (c) demonstrating high ethical standards, (d) showing humanism, (e) practicing social responsibility, and (f) demonstrating sensitivity to people’s cultures and beliefs (Yoder, 2017). Physicians describe professionalism as the moral, cognitive, and collegial aspects of practice (Tobin & Truskett, 2020). Examples of how professionalism manifests is putting patients first, managing conflicts of interest, disclosing errors, self-regulating, and advocating (Tobin & Truskett, 2020). The difference between how professions conceptualize professionalism is of importance because studies have shown that professionalism is part of the process of developing a professional identity. For instance, authors have suggested that values, which are central components of professionalism, impact how people perceive their identity as professionals (Drolet & Désormeaux-Moreau, 2016). Positive effects of having a strong professional identity were shown regarding professionals’ well-being and satisfaction (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011), as well as retention of individuals within the profession (Ashby et al., 2016). Furthermore, studies have shown that a vague professional identity may have negative collective consequences for a profession, such as weak quality of services offered to the population (Drolet & Désormeaux-Moreau, 2014, 2016). Thus, it is important to explicitly define what professionalism is for occupational therapists to favour a strong and specific professional identity.

Occupational therapists showed interest in the concept of professionalism during the past 65 years. In fact, a content analysis of the Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lectures, published from 1955 to 1985 in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, suggested that professionalism was one of the most discussed subjects during those years (DeBeer, 1987). From a historical understanding of professionalism in occupational therapy, it appears that the first definitions mainly considered observable behaviours, such as continuing education or self-evaluation (Parham, 1987). A few years later, other works suggested that this behavioural definition of professionalism was superficial and did not consider the intrinsic motivation of occupational therapists to show professionalism. The authors then suggested that professionalism should be defined as a combination of extrinsic and intrinsic manifestations, and should also consider values such as altruism (Kanny, 1993) or integrity (Peloquin, 2007). DeIuliis (2017), in a recent occupational therapy book, stated, “Professionalism can be described as the attributes, characteristics, or behaviours that are not explicitly part of the profession’s core of knowledge and technical skills but are nevertheless required for success in the profession” (p. xv). This definition is aligned with the task-oriented paradigm of professionalism construction, which is based on a list of selected characteristics that are expected to be applied by professionals (Colley et al., 2007). This paradigm allows occupational therapy students and new graduates to understand professionalism because of the concrete expectations it proposes (Reiter et al., 2018). However, experienced occupational therapists may find it superficial because they have a more profound understanding of professionalism as they have had opportunities to internalize it (Robinson et al., 2012). Task-oriented definitions are also mainly prescriptive and do not consider that professionalism may manifest itself in different ways, which have been evoked in the sociological evolution of professionalism in occupational therapy (Breines, 1988; Remmel-McKay, 1975).

According to Colley et al. (2007), another paradigm of professionalism construction is proposed in the literature. Instead of being task-oriented, it is person-oriented. This second paradigm relies on a more intrinsic way of understanding professionalism. Without prescribing specific behaviours, values, or attitudes, it is about the ways occupational therapists mobilize and manage these resources to resolve conflictual situations or dilemmas they encounter in their daily work (Colley et al., 2007). In accordance with the person-oriented paradigm, Mackey (2014) proposed the following definition of professionalism in occupational therapy: “Professionalism can be conceived as a reflexive ethical concept in that it is through the process of reflecting on the discursive and behavioural options and values available that occupational therapists come to understand, and define their professional selves” (p. 1). This definition would better suit experienced occupational therapists and may be too abstract for students or new graduates (Robinson et al., 2012). However, definitions based on this second paradigm would be less prescriptive and allow for individual ways to express professionalism, which is expected in occupational therapy, as professionalism should be collectively defined but individually applied according to personal and contextual differences (Wood, 2004).

In sum, shortcomings remain in the literature in offering an operational definition of professionalism guiding occupational therapists in their day-to-day work. The occupational therapy literature recognizes professionalism as a multidimensional concept (Bossers et al., 1999; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015), but many papers address only one dimension, such as values (e.g. Aguilar et al., 2012) or behaviours (e.g. Adam et al., 2013). Moreover, professionalism is recognized as a complex concept including reflexivity and dilemma resolution, but the links and dynamic processes between these different inner characteristics have not been comprised in a definition of the concept. Thus, there is a need to offer a comprehensive definition of professionalism in occupational therapy, including all its characteristics and the relations between them. In addition, the literature concerning professionalism in occupational therapy does not provide a clear description of the characteristics comprising the concept, including (a) manifestations of the concept, (b) antecedents required to favour its development, and (c) consequences following its implementation in real life (Walker & Avant, 2011).

Recognizing professionalism in the practice of occupational therapists by identifying its manifestations, notably by identifying its attributes, is crucial. Furthermore, understanding the antecedents to favour for professionalism to take place is essential to support the development of professionalism amongst occupational therapy students or to promote its maintenance amongst clinicians. Finally, questioning the outcomes of professionalism in occupational therapy is critical.

Studies on professionalism have mainly been conducted amongst specific occupational therapy populations, such as students (e.g., Campbell et al., 2015). Other authors have defined professionalism for occupational therapists of specific geographical regions, such as Australia (e.g., Aguilar et al., 2013). Even if we recognize that professionalism may manifest differently amongst occupational therapists across the planet, there is a need for a collective and wider definition of the concept, which goes beyond the national borders and suits all occupational therapy populations. To enhance our feeling of belonging to the profession and to ensure quality services offered to the population across the globe, it is vital to build a common understanding of what professionalism in occupational therapy is. This would lead occupational therapists in the development of a professional identity that is collective and unique. Since international manuscripts have raised issues related to the development of the professional identity of occupational therapists (Ikiugu & Schultz, 2006; Richard et al., 2012; Turner, 2011; Wilcock, 2000), establishing a clear basis of a common definition of professionalism would be beneficial to the advancement of the profession.

Given these gaps in the current state of knowledge, the question of “What is professionalism in occupational therapy?” remains partially answered. As the understanding of professionalism appears to be commonly assumed rather than clearly explained (Bryden et al., 2010; van Mook et al., 2009), conducting a study to provide an operational definition of professionalism in occupational therapy (i.e., exposing clear attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the concept) is vital, thereby providing resources to promote its manifestation in day-to-day practices and allowing the construction of a strong professional identity.

Thus, this study aimed to provide an operational definition of the concept of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Method

Design

A concept analysis research design was used to conduct this study (Walker & Avant, 2011). This design was chosen because it goes further than a linguistic exercise; it is part of a theoretical construction approach. It enables clarifying ambiguous, overused, or unexplored concepts to obtain an operational definition underlining specific characteristics, such as attributes, antecedents, and consequences. The Walker and Avant (2011) concept analysis method is a recognized application in health of the method developed by Wilson (1963) in education. This design highlights the relations amongst the characteristics defining a concept. It has been described in the occupational therapy literature (Tremblay-Boudreault et al., 2014) and applied to various concepts such as preventive behaviours at work (Lecours & Therriault, 2017), quality of life (Levasseur et al., 2006), and social participation (Lariviere, 2008).

Procedure and Analysis

A systematic five-step approach was used to collect relevant documents about the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of professionalism in occupational therapy.

1. Identify the research question

The question should be broad and open in including as many relevant documents as possible, and the core concept must be specified. The target question for this study was the following: What is professionalism in occupational therapy?

2. Select relevant documents

To investigate how professionalism in occupational therapy is defined, a meta-narrative review was conducted (Wong et al., 2013). This type of literature review was chosen because it allows the interpretation of the meaning of terms, which is compatible with the concept analysis design. Furthermore, meta-narrative reviews propose a systematic method that offers the flexibility required to include diverse types of documents (Wong et al., 2013). Initially, distinct combinations of keywords related to the research question and aligned with our knowledge of the literature about professionalism were proposed to search for documents from the relevant scientific databases (Table 1). The keywords and search strategies were developed by two researchers and validated by a librarian with accurate knowledge of occupational therapy literature. The reference lists of the selected documents were also examined manually to ensure literature saturation. Moreover, the gray literature was explored to include theses, professional papers, institutional documents, and textbooks. To do so, a search in Google with the same keywords as those used for the scientific databases was performed. The following inclusion criteria were used to select relevant documents: (a) documents concerning occupational therapy and (b) documents addressing the concept of professionalism (i.e., documents proposing a definition of professionalism or a description of attributes, antecedents, or consequences). Documents addressing values, attitudes, or behaviours adopted by occupational therapists, without making links with professionalism, were excluded. For feasibility reasons, only documents written in French or English were selected, and no limit regarding publication dates was imposed.

Table 1.

Search Strategy.

| Keywords | Databases and Search Engines |

|---|---|

| ‘occupational therap*’, professionalism, ‘professional value*’, ‘professional attitude*’, ‘professional behaviour*’ | Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Medline, Eric, PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane library, OTseeker and Google |

Note: Terms were searched in the title, abstract and keyword fields of each database. Multiple combinations of keywords were used.

3. Study the selection

Primarily, the selected documents were integrated into the Endnote X9 reference management software. After the elimination of duplicates, two researchers checked for the relevance of all documents based on the title, abstract, and keywords. When ambiguity was present, the document was read entirely to determine its inclusion in the study. Regular peer-debriefing meetings amongst the researchers took place to rule on the inclusion or rejection of the documents (Padgett, 2017). This regular communication amongst researchers heightened their reflexivity and guarded against the undue influence of any one’s perspective.

4. Extract and chart data

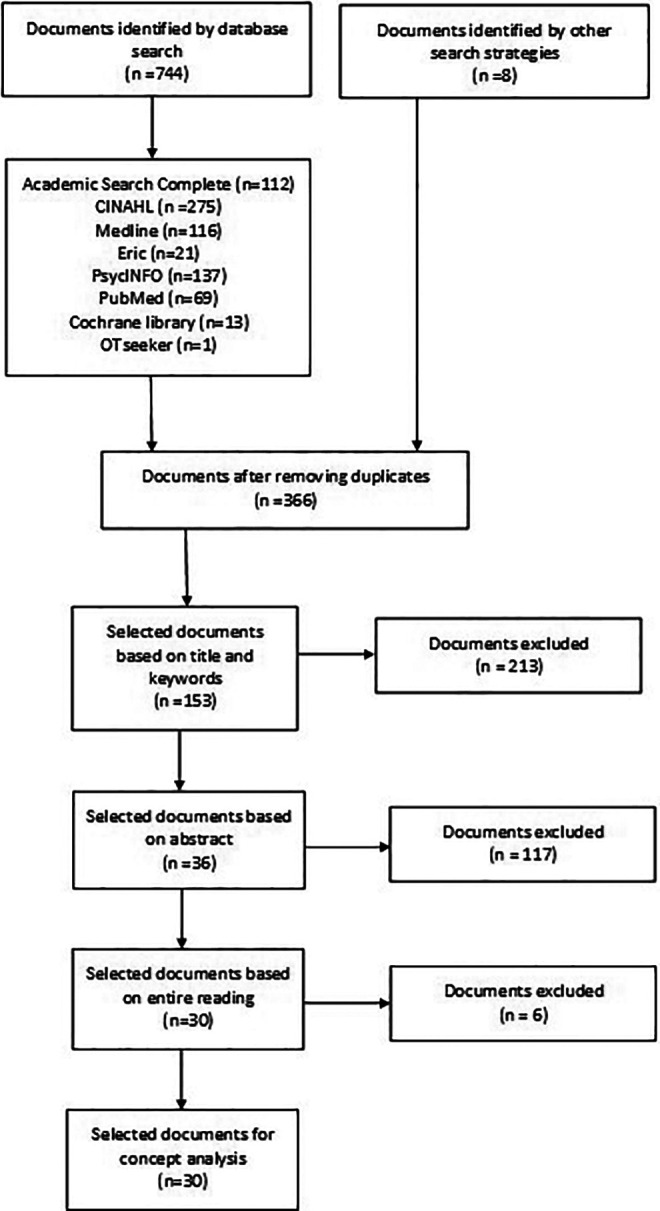

Data on the selected documents were classified according to an adaptation of an extraction grid developed for concept analysis in occupational therapy (Tremblay-Boudreault et al., 2014). The extraction grid included considerable descriptive information about the study (e.g., authors and country), methodological information (e.g., participants and study design), and results (e.g., attributes, antecedents, and consequences of professionalism). This grid was used by two researchers to extract information from five documents. Subsequently, a peer-debriefing meeting took place amongst researchers to modify or adjust the grid as needed. The modified grid was used to extract the information of three other documents before being modified again to improve its validity. These validation steps allowed the researchers to obtain the final version of the grid, which was used to extract the information of all selected documents. Following this systematic research process, a total of 30 reviewed documents 1 were included in the analyses, as shown in the flowchart presented in Figure 1. The information of 12 documents out of 30 (40%) was extracted by two researchers to ensure scientific rigour.

Figure 1.

Documents’ selection flowchart.

5. Analyze the data

The data were examined using the template analysis as an analytical strategy. Template analysis is a form of thematic analysis that is compatible with several qualitative research designs (Crabtree & Miller, 1992). Template analysis has also been found useful in analyzing information from the literature (Crabtree & Miller, 1992). Given that this study aimed to build new knowledge based on the literature, the template analysis was a relevant strategy to achieve the research aim.

Template construction strategy

Initially, a reading of the entire corpus (i.e., data gathered in the extraction grid) was undertaken to obtain a sense of the whole. Several other readings were then conducted to ensure a sense of the immersion of the researchers into the data corpus. The initial coding then started, and the descriptive codes were used and assigned to meaning units (single ideas) found during the data corpus review. The aim of the study was kept in focus to ensure the relevance of the proposed coding. In doing so, the codes were intended to help define the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of professionalism in occupational therapy. The next step consisted of proposing categories and themes. The codes (micro level) were grouped into categories (meso level) and broader themes (macro level). Based on the concept analysis design, three a priori themes (i.e., a: attributes, b: antecedents, and c: consequences) were used to group emerging codes into categories and themes from which a general structure was generated. This step enabled the researchers to propose links amongst the retained codes, categories, and themes. Multiple rounds of applying the extraction grid data to the general structure made the fine-tuning of the analytical process possible.

The analyses were conducted by two researchers. Other members of the research team periodically checked the meaning units identified, codes assigned, and structure produced throughout the analytical process.

Ethics

Institutional ethics approval was not required for the secondary analysis of already published data.

Findings

Description of the Selected Documents

Although there were no restrictions on publication dates, the selected documents were mostly recent. More than 60% had been published in the last 10 years. Three documents were written in French, with the others all being in English. Half of the selected documents were scientific articles, institutional documents, and opinion articles. A textbook was also selected. Diverse types of occupational-therapy-related participants including clinicians, students, educators, or trainee supervisors were represented in the documents. The participants most often came from North America, but some studies included participants from other continents such as Europe, Oceania, Africa, and Asia. Table 2 describes the characteristics of the selected documents.

Table 2.

Description of the Selected Documents (n = 30).

| Number of Documents (%) | |

|---|---|

| Date of publication | |

| 2011 and after | 19 (63.4%) |

| 2000–2010 | 7 (23.3%) |

| Before 1999 | 4 (13.3%) |

| Publication language | |

| English | 27 (90.0%) |

| French | 3 (10.0%) |

| Types of documents | |

| Scientific articles | 17 (56.7%) |

| Institutional documents | 4 (13.3%) |

| Opinion articles | 8 (26.7%) |

| Textbooks | 1 (3.3%) |

| Types of participants* | |

| Occupational therapists: Clinicians | 7 (17.9%) |

| Occupational therapy students | 7 (17.9%) |

| Occupational therapists: Classroom educators | 4 (10.3%) |

| Occupational therapy assistants | 2 (5.1%) |

| Occupational therapists: Placement educators | 2 (5.1%) |

| Occupational therapists: Trainee supervisors | 1 (2.6%) |

| Not applicable/not specified | 16 (41.1%) |

| Continent of the origin of the participants | |

| America | 9 (30.0%) |

| Europe | 2 (6.7%) |

| Africa | 1 (3.3%) |

| Asia | 1 (3.3%) |

| Oceania | 1 (3.3%) |

| Not applicable/not specified | 16 (53.4%) |

* Some documents include more than one type of participants; hence, the total number of participant types exceeds the number of selected documents.

Operational Definition of Professionalism in Occupational Therapy

The findings from our concept analysis led to the following operational definition of professionalism in occupational therapy:

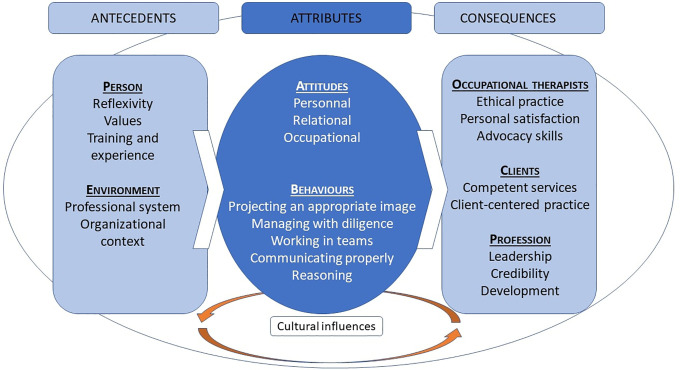

Professionalism in occupational therapy refers to the development of an individual as an occupational therapist serving the public in a distinct way. It is developed within a professional system and organizational context, and emerges from certain individual characteristics such as reflexivity, values, and training/experience. Professionalism is characterized by personal (e.g., being confident), relational (e.g., being devoted), and occupational (e.g., being organized) attitudes and distinctive behaviours such as projecting an appropriate image, managing with diligence, working in teams, communicating properly, and reasoning to address clinical issues. Professionalism in turn leads to ethical behaviour, and satisfied practitioners who are able to advocate for recipients of their services. As a result, clients are satisfied because they receive competent and client-centred services from the practitioners. The professionals in the discipline become good leaders, and the profession increases its credibility and develops a strong, positive identity. The proposed definition also recognizes the ubiquitous cultural influences that generate differences in the development, manifestations, and consequences of professionalism.

For illustration of the aforementioned operational definition of professionalism, please see Figure 2

Figure 2.

Antecedents, attributes, and consequences of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Figure 2 shows the specific characteristics defining professionalism, and exposes the relation between its antecedents, attributes, and consequences. The figure also highlights the constant cultural influences impacting the process of development, manifestations, and consequences of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Description of Attributes, Antecedents, and Consequences of Professionalism

The analysis of the selected documents allowed us to describe with precision and specificity the attributes, antecedents, and consequences comprising the proposed operational definition of professionalism in occupational therapy.

Attributes

Attributes are characteristics that enable the recognition of the concept in reality (Walker & Avant, 2011). Following the exhaustive literature review, the attributes of the concept of professionalism in occupational therapy are attitudes and behaviours, as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Attributes of Professionalism in Occupational Therapy.

| Attitudes |

Personal |

| Positive | |

| Patient | |

| Confident | |

| Mature | |

| Motivated | |

| Relational | |

| Weighted | |

| Humble | |

| Attentive | |

| Devoted | |

| Nice | |

| Declarative | |

| Occupational | |

| Creative | |

| Reliable | |

| Flexible | |

| Organised | |

| Involved | |

| Responsible | |

| Persevering | |

| Behaviours | Projecting an appropriate image |

| Managing with diligence | |

| Time | |

| Resources | |

| Working in teams | |

| Collaborating | |

| Cooperating | |

| Communicating properly | |

| Verbal | |

| Non-verbal | |

| Written | |

| Reasoning | |

| Adopting critical thinking | |

| Exercising clinical judgment |

Attitudes, which are manifestations of soft skills of a person (i.e., personality traits that enable a person to interact with the environment; Schulz, 2008), are divided into three types regarding professionalism in occupational therapy: (a) personal, (b) relational, and (c) occupational. Our analysis led to the identification of five personal attitudes that a professional occupational therapist may manifest, which are being positive, patient, confident, mature, and motivated. For instance, Kasar and Muscari (2000) 2 suggested that having a positive attitude about the role of occupational therapists is a manifestation of professionalism. For other authors, professionalism implies an occupational therapist who undertakes projects and takes initiatives with motivation (Campbell et al., 2015; Kasar & Muscari, 2000; Mason & Mathieson, 2018). Relational attitudes include being weighted, humble, attentive, devoted, nice, and declarative. DeIuliis (2017) demonstrated that professional occupational therapists must be weighted in their relationships; they must have “the ability to self-regulate or maintain emotional stability” (p. xxxi). Professionalism also implies that occupational therapists show an attentive attitude while communicating with clients (Mason & Mathieson, 2018) and colleagues (Campbell et al., 2015), and in other circumstances as well, such as attending a conference (Randolph, 2003). Concerning attitudes that are occupation-centred, we identified seven attributes of professionalism, which are being creative, reliable, flexible, organized, involved, responsible, and persevering. According to several authors, professionalism requires occupational therapists to have a “creative approach to health” (Adam et al., 2013, p. 80) by improvising and thinking outside the box (Campbell et al., 2015) or by using creativity to solve problems (Aguilar et al., 2013). Another example of an occupation-centred attitude is flexibility. In other words, occupational therapists must be “adaptive to different contexts” (Burford et al., 2014, p. 367) such as patients’ situations, physical environments, or specificities of the clinical demand.

Behaviours, which are observable actions of individuals, were divided into five categories. The first behaviour that was identified is projecting an appropriate image. Studies have suggested that adequate dressing and grooming (Bossers et al., 1999) “inspire trust and confidence” (Burford et al., 2014, p. 369) and is a sign of professionalism. The second behaviour that was found to be an attribute of professionalism is managing with diligence. For instance, authors suggested that properly managing time (Adam et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2015; Glennon & Van Oss, 2010; Kasar & Muscari, 2000; Randolph, 2003; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015) or managing resources in an efficient manner (Bossers et al., 1999; Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2017) are manifestations of professionalism for occupational therapists. Working in teams was the third behaviour that formed part of the attributes of professionalism. For Glennon et al. (2010), this behaviour is important to grow as a professional because “working collaboratively [allows one] to maximize one’s own learning experiences” (p. 14). The fourth behaviour defining professionalism in occupational therapy was communicating properly, verbally, non-verbally, and in writing. For instance, Campbell et al. (2015) suggested that communicating with an “appropriate language level with clients” (p. 5) is a manifestation of this attribute. Finally, reasoning was the last behaviour that formed part of the attributes of professionalism in occupational therapy. This behaviour implies adopting critical thinking and exercising clinical judgment. For example, Kasar and Muscari (2000) reported the importance of “analyzing, synthesizing, and interpreting information” (p. 44) as part of professional behaviours. Another example has been found in the manuscript of Parham (1987), in which she reported the importance for occupational therapists to “critique [their] own clinical thinking. Develop an awareness of how [they] are naming and framing clinical problems” (p. 560).

Antecedents

Antecedents are events, characteristics, and incidents that must be in place before the occurrence of the concept (Walker & Avant, 2011). Our literature review suggested that antecedents related to the person and environment are required for professionalism to take place, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Antecedents of Professionalism in Occupational Therapy.

| Person | Reflexivity |

| Introspection | |

| Analytical skills | |

| Recognition of one’s limits | |

| Values | |

| Shared with other allied health professionals— | |

| Empathy | |

| Integrity | |

| Health | |

| Altruism | |

| Opening | |

| Respect | |

| Honesty | |

| Human rights | |

| Sense of duty | |

| Specific to occupational therapy—Occupational values | |

| Enablement | |

| Occupational engagement | |

| Occupational balance | |

| Occupational participation | |

| Occupational performance | |

| Occupational signification | |

| Occupational justice | |

| Training and experience | |

| Education and professional development | |

| Work experience | |

| Environment | Professional system |

| Regulations and laws | |

| Codes of ethics | |

| Policies and procedures | |

| Organizational context | |

| Expectations of the organization | |

| Organizational functioning |

Concerning person-related antecedents, our analysis revealed that reflexivity is important in the development of professionalism. According to the authors, reflexivity includes the capacity of introspection (Aguilar et al., 2012; Bossers et al., 1999; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015), analytical skills (Campbell et al., 2015; Drolet & Désormeaux-Moreau, 2016; Mackey, 2014), and recognition of one’s limits (Hordichuk et al., 2015; Randolph, 2003; Robinson et al., 2012). Another person-related antecedent concerns values. Our concept analysis allowed one to understand that both values shared with other allied health professionals and occupational therapy-specific values are required for professionalism to occur. For instance, authors have suggested that having a “strong sense of empathy” (DeIuliis, 2017, p. xxix), “respect for people’s language, culture and views” (Aguilar et al., 2013, p. 211), and “honesty […] by being transparent and authentic” (Drolet & Desormeaux-Moreau, 2015, p. 279) are shared values among allied health professionals that are antecedents to professionalism. Our analysis also proposed that individuals must develop specific occupational values such as enablement, including valorizing clients’ self-determination; and believing in clients’ potential (Aguilar et al., 2012, 2013; CAOT, 2012; Dillon, 2002; Mason & Mathieson, 2018; Nortje & De Jongh, 2017; Université Laval, 2019), occupational engagement, occupational balance, occupational participation, occupational performance, occupational signification (Aguilar et al., 2012, 2013; Hordichuk et al., 2015; Légis Québec, 2018), and occupational justice, including advocating for occupational opportunities and occupational rights (Aguilar et al., 2012; Burford et al., 2014; Hordichuk et al., 2015; Kasar & Muscari, 2000; Légis Québec, 2018; Nortje & De Jongh, 2017; Robinson et al., 2012). Finally, training and experience should also be considered person-related antecedents of professionalism in occupational therapy. For instance, the literature suggests that professional occupational therapists are “qualified by education, training, and/or experience to practice capably and safely in [their] chosen role” (Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2017, p. 14). For students or new graduates, fieldwork experience would be of importance for development of professionalism (Glennon & Van Oss, 2010), notably because it allows one to understand roles and responsibilities, and to apprehend how to manage knowledge in concrete situations (Bossers et al., 1999; Robinson et al., 2012). Furthermore, education, professional development, and work experience have an influence on the development of professionalism. For instance, Nortje and De Jongh (2017) suggested that continuous professional development training is an important factor in maintaining professionalism for clinicians.

Environmental antecedents concern the professional system and the organizational context in which occupational therapists evolve. The professional system, with its regulations and laws (Bossers et al., 1999; Burford et al., 2014; CAOT, 2012; DeIuliis, 2017; Nortje & De Jongh, 2017; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015; Université Laval, 2019), codes of ethics (Bull, 2007; Randolph, 2003; Robinson et al., 2012), policies, and procedures (Burford et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2015; Mason & Mathieson, 2018; Robinson et al., 2012) has an influence on how professionalism develops and takes place on a daily basis. The organizational context with expectations of organizations and organizational functioning was also an antecedent of professionalism. For instance, Robinson et al. (2012) revealed that how workplace communicates expectations to professionals has an impact on the development and manifestation of professionalism. Concurrently, Adam et al. (2013) have highlighted that “organizational issues” (p. 82) impact professionalism of occupational therapists.

Consequences

After the identification of the concept, examining the consequences of the occurrence of the concept is possible. Our concept analysis revealed that professionalism has tangible consequences to the professionals, service recipients, and the profession at large as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Consequences of Professionalism in Occupational Therapy.

| For the occupational therapists | Ethical practice |

| Personal satisfaction | |

| Advocacy skills | |

| For the clients | Competent services |

| Client-centred practice | |

| For the profession of occupational therapy | Leadership |

| Credibility | |

| Development |

For the occupational therapists themselves, professionalism may lead to ethical practice. For Drolet and Désormeaux-Moreau (2015), the internalization of professionalism components that are values may help occupational therapists “to facilitate the resolution of ethical challenges posed by professional practice” (p. 282). Personal satisfaction (Weppler, 1973) and development of advocacy skills (Aguilar et al., 2012, 2013; Bossers et al., 1999; Glennon & Van Oss, 2010; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015) were also consequences of professionalism for occupational therapists. For clients, professionalism in occupational therapy tends to ensure that they receive competent and client-centred services. The authors reported that being professional lead occupational therapists to be “clinically competent” (Campbell et al., 2015, p. 5; Nortje & De Jongh, 2017, p. 42;). For Glennon and Van Oss (2010), adopting professional attitudes and behaviours may “improve client-centred interventions” (p. 13). Finally, for the profession of occupational therapy, the occurrence of professionalism may lead to increased leadership in the profession. In fact, leadership is an important consequence of professionalism as the authors stated that it enables occupational therapists to develop leadership roles (Bossers et al., 1999) in their workplace (Aguilar et al., 2012), but also more globally in the healthcare system (Aguilar et al., 2013). Another consequence of professionalism is better credibility of the profession for the population. This idea was found in several manuscripts, including one of Remmel-McKay (1975) published in the 1970 s stating that professionalism in occupational therapy “has encouraged greater assumption of authority and greater inputs into the total health industry” (p. 108). Finally, the last consequence of professionalism we identified was related to the ongoing development of occupational therapy (Aguilar et al., 2013; Bossers et al., 1999; Dillon, 2002; Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2017; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015), contributing to a strong and unique professional identity.

In addition to the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of professionalism discussed earlier, our analysis also revealed that culture has an influence on professionalism. The analysis allowed one to understand that culture impacts on the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of professionalism. The literature proposes that different cultural aspects may influence professionalism such as the societal (Wood, 2004), individual (Davys et al., 2006; Wood, 2004), generational (Reiter et al., 2018), or organizational (Burford et al., 2014) aspects of culture. As an example, Reiter et al. (2018) have suggested differences in how occupational therapists of “various generations interpret and display [professional] behaviours” (p. 3). Another example concerning the individual aspect of culture was provided by Davys et al. (2006) as they explained how personal presentation and appearance of occupational therapists may differ. They explained that personal presentation is a way of expressing one’s identity. Burford et al. (2014) have explained how organizational culture influences professionalism of occupational therapists. For instance, support (or a lack of) from superiors or peers may enhance or inhibit the manifestation of professionalism. Therefore, the influence of culture may lead to variations in the development, manifestations, and consequences of professionalism.

Discussion

Based on the data extraction of 30 documents from the literature in occupational therapy, this concept analysis proposed a definition of professionalism in occupational therapy. The identification of attributes, antecedents, and consequences suggest concrete levers to identify, develop, or implement professionalism in the practice of occupational therapists.

Professionalism as a Developmental Process: The Importance of Antecedents

This study was innovative as previous reflections and studies on professionalism have mainly focused on attributes, showing less interest in antecedents or consequences. This different understanding of professionalism, focusing on the variables upstream of the manifestation of the concept, may have led to the proposal of a distinct definition, especially concerning the values and parameters of the professional system. In fact, other authors have suggested that these characteristics define professionalism as part of its attributes (Aguilar et al., 2012, 2013; Bossers et al., 1999; Bull, 2007; CAOT, 2012; Hordichuk et al., 2015; Kasar & Muscari, 2000; Mason & Mathieson, 2018; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015). However, our concept analysis allowed one to understand that the values and parameters of the professional system are antecedents of professionalism, just as reflexivity, training, experience, and organizational context. In fact, the values and parameters of the professional system are not manifestations of professionalism; they do not allow for recognition.

Values are abstract axiological or evaluative constructs that are not perceptible in real life (Drolet, 2014). However, they influence professional practices in the sense that occupational therapists must first adhere to values, such as empathy or occupational justice, to show professionalism through its attitudes and behaviours. This reflection suggests that values are more likely to be antecedents than attributes of professionalism. This important idea reinforces the place that must be given to the transmission of professional values, especially those specific to occupational therapy, to support the development of professionalism amongst students and early career occupational therapists.

In the same way, parameters of the professional system, such as the code of ethics or the regulations and laws, must be well defined before occupational therapists can implement these in professional practice. These elements are also considered as antecedents of professionalism, not as attributes, because they influence the adoption of behaviours and attitudes by occupational therapists. In fact, by being aware of the socially organized sanctions that condemn and punish professional misconduct, occupational therapists may regulate their actions to show professionalism.

This precision concerning antecedents of the concept is in line with the idea of a developmental understanding of professionalism (Reiter et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2012; Sullivan & Thiessen, 2015); some prerequisites must first be acquired and must influence the possibilities of occupational therapists to develop and implement professionalism in their practice.

Professionalism: A Definition Halfway Between the Two Paradigms

Based on the two paradigms of professionalism construction suggested by Colley et al. (2007), our definition includes task-oriented and person-oriented components. In relation to the task-oriented paradigm, the proposed definition includes a list of values, attitudes, or behaviours that were described as being part of what professionalism in occupational therapy is. These should not be considered as requirements, but as levers to be managed. In a developmental understanding of professionalism, these levers may help students and new graduates to understand, in a tangible manner, how to display professionalism (Reiter et al., 2018). Our results also suggested that professionalism is a complex competence, going further than the application of expectations. This implies the interaction of personal, environmental, and occupational variables and it requires a reflexive practice from occupational therapists. In fact, occupational therapists must first develop reflexivity and show introspection and analytical skills in order to be able to recognize their limits. These antecedents enable occupational therapists to demonstrate behaviours related to reasoning, such as adopting critical thinking and exercising clinical judgment. The manifestation of these attributes of professionalism may contribute to ethical practice. The reflexive practice is then part of professionalism in its antecedents, attributes, and consequences. This important characteristic of professionalism is crucial to support occupational therapists’ decision-making processes in complex situations, leading to a fair professional practice (Fulford, 2004). Reflexive practice is also related to the ability of occupational therapists to manage conflictual situations and take thoughtful and meaningful professional actions (Kinsella, 2001). This converges with the person-oriented paradigm of the professionalism construction. This more in-depth part of our definition may appeal to experienced occupational therapists who have an intrinsic experience of professionalism.

Moreover, our definition is not constructed to be prescriptive. Figure 2 proposes categories of antecedents, attributes, and consequences without prescribing specific ways to manifest them. Tables 3 to 5 propose concrete examples of these characteristics based on the literature. However, our understanding of the evolution of the concept suggests the importance of not being prescriptive and allowing room for variations in ways to express professionalism (Remmel-McKay, 1975; Wood, 2004). A non-prescriptive definition of professionalism respects and promotes professional autonomy and the reflective practice of occupational therapists. Cultural influences (e.g., individual, societal, generational, and organizational) that constantly impact the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of professionalism also justify the need to accept variants, dynamism, flexibility, and adaptivity in the development, manifestation, and outcome of professionalism. These cultural influences impacting on how occupational therapists manifest professionalism are in line with previous findings, notably those of Freeman et al. (2009) and Drolet et al. (2020) stating that organizational culture, with its bureaucratic rules and management practices, influences how occupational therapists fulfil their professional obligations.

Professionalism: Based on Shared and Specific Characteristics

Another interesting finding of this study is the idea that some characteristics of professionalism are shared between allied health professions, as others are specific to occupational therapy. In line with other authors suggesting the importance of a profession-specific definition of professionalism (Aguilar et al., 2012; Bryden et al., 2010), we identified values that are unique to occupational therapists. Our analysis of the literature allows one to understand that values of enablement, occupational balance, occupational engagement, occupational participation, occupational performance, occupational signification, and occupational justice are antecedents of professionalism that are specific to occupational therapists. Previous works stated that occupational therapists consider occupation a profession-specific value (Aguilar et al., 2012). Although occupation is deeply rooted in the identity of occupational therapists (Townsend et al., 2013), we cannot consider occupation as a value as it is a concrete descriptive concept and fails to fulfil the requirements of the definition of a value (Drolet, 2014). A valued concept should not automatically be considered a value. We have privileged the inclusion of seven occupational values that are abstract concepts that meet contemporary definitions of values (Drolet, 2013). This conceptual clarification is important for building fair and accurate theories (Hammell, 2009; Phelan, 2011). As theories guide our practices and influence the development of our professional identity (Turner & Knight, 2015), there is a need for a reflection on those professionalism features that are unique to our profession and to deepen those specificities that enrich the complexity and value of occupational therapy.

Why Acting with Professionalism? The Importance of Consequences

Finally, an important contribution of this study for the advancement of knowledge is the identification of the consequences of professionalism. As professionalism was mainly assumed and barely explained (Bryden et al., 2010; van Mook et al., 2009), few authors have examined the consequences of professional practice in occupational therapy. In addition to the adoption of ethical practice, the feeling of personal satisfaction, and the development of advocacy skills for occupational therapists, professionalism contributes to ensuring competent services and a client-centred approach, a fundamental prerequisite for occupational therapists (Townsend et al., 2013). Professionalism is also a means of assuming leadership, attaining credibility, and advancing as a profession. As these consequences are mainly positive for occupational therapists, clients, and the profession, putting in place the antecedents of professionalism and working on the implementation of its attributes are important, thereby leading to the occurrence of these consequences. This process may contribute to the development of a strong and unique professional identity in occupational therapy, responding to the call for a profession-specific definition of professionalism.

Strengths and Limitations

This study proposed a holistic understanding of professionalism, including the definition and identification of links between antecedents, attributes, and consequences. These concrete characteristics offer levers to identify, develop, and implement professionalism in the practice of occupational therapists. The rigorous methodology was presented thoroughly, allowing for replication. However, consistent with the concept analysis design, quality assessment and grading of selected documents were not performed. In addition, it should be recognized that other methods of concept analysis do exist and that maybe the use of another method would have led to different results. Finally, the definition of professionalism proposed is as of today. Consequently, as concepts evolve over time, it is possible that this definition becomes obsolete.

Conclusion

In this study, we proposed an operational definition of the concept of professionalism in occupational therapy, highlighting its antecedents, attributes, consequences, and the constant influence of culture. The results of this study provide an informative, non-prescriptive, and operational definition of professionalism in occupational therapy that is suitable for all occupational therapists, regardless of their age, geographic location, and place of practice. The results obtained suggest concrete implications. For occupational therapists in practice, targets to achieve as part of the professional practice’s continuous development process are now available. Notably, specific attitudes and behaviours to adopt are highlighted. For educational settings, antecedents to promote the development of professionalism amongst students are well defined, such as values to be shared with them. For employing organizations, the organizational context features that enable occupational therapists to manifest professionalism are known. For professional associations, knowledge of the consequences of professionalism proposes strong arguments to advocate supporting the development of this primordial competence in occupational therapy. The next research step will be to determine how culture influences the development, manifestations, and consequences of professionalism. As this is a relevant finding from this study, pursuing our understanding of the influence of culture on professionalism in occupational therapy is crucial.

Key Messages

This article proposes levers to promote the development and maintenance of the concept of professionalism for researchers, practicing occupational therapists, educational settings, and professional associations.

This theoretical work proposes an operational definition of professionalism that suits novice and experienced occupational therapists.

Culture influences the development and manifestation of professionalism in occupational therapy; culture should be considered in any further research about professionalism.

Acknowledgements

The authors thanks Karine L’Écuyer, research assistant, for her help with the literature search.

Author Biographies

Alexandra Lecours is an assistant professor in the Rehabilitation Department at Laval University and a regular researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and Social Integration. Her research interests focus mainly on occupational health, safety and well-being. She is also interested in professional development.

Nancy Baril is a clinical professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR). She is a fieldwork supervisor and teaches health promotion and occupational therapy with children and teenagers.

Marie-Josée Drolet is a full professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR). She teaches ethics and conducts research in this field.

Notes

The list of selected documents for conducting the concept analysis is shown in Appendix 1.

To lighten the text, extracts from the selected documents are shown to illustrate the results. The full list of references supporting each of the identified characteristics of professionalism can be obtained by contacting the first author.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Fonds pour la recherche clinique of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières.

ORCID iD: Alexandra Lecours  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4485-7829

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4485-7829

References

- Adam K., Peters S., Chipchase L. (2013). Knowledge, skills and professional behaviours required by occupational therapist and physiotherapist beginning practitioners in work-related practice: A systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60, 76–84. 10.1111/1440-1630.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar A., Stupans L., Scutter S. (2011). Assessing students’ professionalism: considering professionalism’s diverging definitions. Education for Health, 24(3), 599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar A., Stupans I., Scutter S., King S. (2012). Exploring professionalism: The professional values of Australian occupational therapists. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59(3), 209–217. 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2012.00996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A., Stupans, I, Scutter S., King S. (2013). Towards a definition of professionalism in A ustralian occupational therapy: Using the Delphi technique to obtain consensus on essential values and behaviours. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(3), 206–216. 10.1111/1440-1630.12017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby S. E., Adler J., Herbert L. (2016). An exploratory international study into occupational therapy students’ perceptions of professional identity. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 63(4), 233–243. 10.1111/1440-1630.12271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossers A., Kernaghan J., Hodgins L., Merla L., O’Connor C., Van Kessel M. (1999). Defining and developing professionalism. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(3), 116–121. 10.1177/000841749906600303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breines E. B. (1988). Redefining professionalism for occupational therapy. American journal of occupational therapy, 42(1), 55–57. 10.5014/ajot.42.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden P., Ginsburg S., Kurabi B., Ahmed N. (2010). Professing professionalism: are we our own worst enemy? Faculty members’ experiences of teaching and evaluating professionalism in medical education at one school. Academic medicine, 85(6), 1025–1034. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ce64ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull R. (2007). The concept of professionalism in the New Zealand context. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(2), 42. [Google Scholar]

- Burford B., Morrow G., Rothwell C., Carter M., Illing J. (2014). Professionalism education should reflect reality: findings from three health professions. Medical education, 48(4), 361–374. 10.1111/medu.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2019). Professionalism. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/fr/dictionnaire/anglais/professionalism

- Campbell M. K., Corpus K., Wussow T. M., Plummer T., Gibbs D., Hix S. (2015). Fieldwork educators’ perspectives: Professional behavior attributes of level II fieldwork students. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(4), 7. 10.15453/2168-6408.1146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CAOT. (2012). Profile of occupational therapy practice in Canada. ACE. [Google Scholar]

- Colley H., James D., Diment K. (2007). Unbecoming teachers: towards a more dynamic notion of professional participation. Journal of Education Policy, 22(2), 173–193. 10.1080/02680930601158927 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree B. F., Miller W. L. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Crabtree B. F., Miller W. L. (Eds.), Doing qualitative eesearch. (pp. 93–109). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davys D., Pope K., Taylor J. (2006). Professionalism, prejudice and personal taste: does it matter what we wear? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(7), 339–341. 10.1177/03080226060690070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeer F. (1987). Major themes in occupational therapy: A content analysis of the Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lectures, 1955–1985. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 41(8), 527–531. 10.5014/ajot.41.8.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeIuliis E. D. (2017). Professionalism across occupational therapy practice: Slack Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon T. H. (2002). Practitioner perspectives: effective intraprofessional relationships in occupational therapy. Occupational therapy in health care, 14(3–4), 1–15. 10.1080/J003v14n03_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M.-J. (2013. ). De l’éthique à l’ergothérapie: la philosophie au service de la pratique ergothérapique. Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M.-J. (2014). The axiological ontology of occupational therapy: A philosophical analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 21(1), 2–10. 10.3109/11038128.2013.831118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M.-J., Désormeaux-Moreau M. (2014). Les valeurs des ergothérapeutes: résultats quantitatifs d’une étude exploratoire. Bioéthique Online, 3, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M.-J., Désormeaux-Moreau M. (2016). The values of occupational therapy: Perceptions of occupational therapists in Quebec. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 23(4), 272–285. 10.3109/11038128.2015.1082623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet M.-J., Lalancette M., Caty M.-È. (2020). «Brisées par leur travail! OU Au bout du rouleau»: réflexion critique sur les modes managériaux en santé. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 3(1). [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A. R., McWilliam C. L., MacKinnon J. R., DeLuca S., Rappolt S. G. (2009). Health professionals’ enactment of their accountability obligations: Doing the best they can. Social Science & Medicine, 69(7), 1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulford K. (2004). Chapter 14. Facts/values. Ten principles of values-based medicine. In Philosophy Canada (Vol. 57, pp. 113–122). Oxford Press University. [Google Scholar]

- Glennon T. J., Van Oss T. (2010). Identifying and promoting professional behavior: best practices for establishing, maintaining, and improving professional behavior by occupational therapy practitioners. OT Practice, 15(17), 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hammell K. W. (2009). Les textes sacrés: Un examen sceptique des hypothèses qui sous-tendent les théories sur l’occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(1), 14–22. 10.1177/00084174090760010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hordichuk C. J., Robinson A. J., Sullivan T. M. (2015). Conceptualising professionalism in occupational therapy through a Western lens. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(3), 150–159. 10.1111/1440-1630.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikiugu M. N., Schultz S. (2006). An argument for pragmatism as a foundational philosophy of occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(2), 86–97. 10.2182/cjot.05.000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanny E. (1993). Core values and attitudes of occupational-therapy practice. American Occupational Therapy Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kasar J., Muscari M. E. (2000). A conceptual model for the development of professional behaviours in occupational therapists. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(1), 42–50. 10.1177/000841740006700107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella E. A. (2001). Reflections on reflective practice. Canadian journal of occupational therapy., 68(3), 195. 10.1177/000841740106800308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lariviere N. (2008). Analyse du concept de la participation sociale: definitions, cas d’illustration, dimensions de l’activite et indicateurs. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 114. 10.1177/000841740807500207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecours A., Therriault P.-Y. (2017). Preventive behavior at work - A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(4), 1–10. 10.1080/11038128.2016.1242649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légis Québec. (2018). Code de déontologie des ergothérapeutes. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ShowDoc/cr/C-26,%20r.%20113.01/.

- Levasseur M., Tribble D. S.-C., Desrosiers J. (2006). Analyse du concept qualité de vie dans le contexte des personnes agées avec incapacités physiques. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3), 163–177. 10.2182/cjot.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey H. (2014). Living tensions: Reconstructing notions of professionalism in occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(3), 168–176. 10.1111/1440-1630.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason V. C., Mathieson K. (2018). Occupational therapy employers’ perceptions of professionalism. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 6(1), 9. 10.15453/2168-6408.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. (2019). Professionalism. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/professionalism

- Nortje N., De Jongh J. (2017). Professionalism-A case for medical education to honour the societal contract. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47(2), 41–44. 10.17159/231-3833/1017/v47n2a7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Parham D. (1987). Toward professionalism: The reflective therapist. American journal of Occupational Yherapy, 41(9), 555–561. 10.5014/ajot.41.9.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloquin S. M. (2007). A reconsideration of occupational therapy’s core values. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(4), 474–478. 10.5014/ajot.61.4.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S. K. (2011). Constructions of disability: a call for critical reflexivity in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78(3), 164–172. 10.2182/cjot.2011.78.3.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph D. S. (2003). Evaluating the professional behaviors of entry-level occupational therapy students. Journal of Allied Health, 32(2), 116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter K., Helgeson L., Lee S. C. (2018). Enhancing professionalism among OT students: The culture of professionalism. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 2(3), 8. 10.26681/jote.2018.02030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remmel-McKay A. M. (1975). Sociological overview of professionalism in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 42(3), 104–109. 10.1177/000841747504200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard C., Colvez A., Blanchard N. (2012). État des lieux de l’ergothérapie et du métier d’ergothérapeute en France. Analyse des représentations socioprofessionnelles des ergothérapeutes et réflexions pour l’avenir du métier. ErgOthérapies(48), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson A. J., Tanchuk C. J., Sullivan T. M. (2012). Professionalism and occupational therapy: An exploration of faculty and students’ perspectives. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(5), 275–284. 10.2182/CJOT.2012.79.5.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists. (2017). Professional standards for occupational therapy Practice. https://www.rcot.co.uk/practice-resources/rcot-publications/downloads/professional-standards

- Schulz B. (2008). The importance of soft skills: Education beyond academic knowledge. Nawa Journal of Communication , 2(1), 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Skorikov V. B., Vondracek F. W. (2011). Occupational identity. In Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 693–714): Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. M., Thiessen A. K. (2015). Occupational therapy students’ perspectives of professionalism: An exploratory study. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(4). 10.15453/2168-6408.1154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin S. A., Truskett P. G. (2020). Professionalism for surgeons. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 90(6), 1153–1159. 10.1111/ans.15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend E. A., Beagan B., Kumas-Tan Z., Versnel J., Iwana M., Landry J., Stewart D., Brown J. (2013). Habiliter: la compétence primordiale en ergothérapie (Cantin N., Trans.). In Townsend E. A., Polatajko H. J. (Eds.), Habiliter à l’occupation (2nd ed., pp. 103–158). Association Canadienne des Ergothérapeutes. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay-Boudreault V., Durand M.-J., Corbière M. (2014). L’analyse de concept: Description et illustration de la charge de travail mentale. In Corbière M., Larivière N. (Eds.), Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes (pp. 123–143). Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Turner A. (2011). The Elizabeth Casson Memorial Lecture 2011: Occupational therapy—A profession in adolescence? British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(7), 314–322. 10.4276/030802211X13099513661036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A., Knight J. (2015). A debate on the professional identity of occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78(11), 664–673. 10.1177/0308022615601439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Université Laval. (2019). Référentiel de compétences du programme d’ergothérapie. Université Laval.

- van Mook W. N., de Grave W. S., Wass V., O’Sullivan H., Zwaveling J. H., Schuwirth L. W., van der Vleuten C. P. (2009). Professionalism: Evolution of the concept. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 20(4), e81–e84. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. O., Avant K. C. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Weppler C. (1973). The acquisition of professionalism. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40(2), 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock A. A. (2000). Development of a personal, professional and educational occupational philosophy: An Australian perspective. Occupational Therapy International, 7(2), 79–86. 10.1002/oti.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. (1963). Thinking with concepts. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong G., Greenhalgh T., Westhorp G., Buckingham J., Pawson R. (2013). RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC medicine, 11(1), 20. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W. (2004). The heart, mind, and soul of professionalism in occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Rherapy, 58(3), 249–257. 10.5014/ajot.58.3.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder L. (2017). Professionalism in nursing. MEDSURG Nursing, 26(5), 293–294. [Google Scholar]