This cross-sectional study evaluates the association between lifetime earning potential and workforce distribution and the potential role of a pediatric subspecialist–specific loan repayment program in workforce expansion.

Key Points

Question

Do differences in lifetime earning potential between pediatric subspecialties play a role in workforce shortages?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 7539 pediatric subspecialists found that lower lifetime earning potential, seen in certain pediatric subspecialties, was significantly associated with multiple measures of current workforce distribution and lower fellowship fill rates. Subspecialties with weaker growth in earning potential throughout the past 10 years have experienced restricted workforce expansion.

Meaning

The lifelong financial returns of pediatric fellowship training and subspecialty of choice may contribute to imbalances in both the current and future pediatric workforce; interventions to improve the financial returns of fellowship training, such as pediatric subspecialist–specific loan repayment programs, are potential tools for policy makers to target workforce shortages.

Abstract

Importance

Differences in lifetime earning potential between pediatric subspecialties may contribute to shortages in the subspecialty workforce.

Objectives

To evaluate the association between lifetime earning potential and workforce distribution and to investigate the potential role of a pediatric subspecialist–specific loan repayment program (LRP) in workforce expansion.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was performed on publicly available mean debt and compensation data from national physician surveys from 2018 to 2019 of pediatric subspecialists in academic practice. Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between lifetime earning potential and measures of workforce distribution in 2019, including distance to subspecialists, percentage of hospital referral regions with a subspecialist, and ratio of subspecialists to the regional child population as well as between lifetime earning potential in 2018 to 2019 and mean subspecialty fellowship fill rates between 2014 and 2018. The association between the change in lifetime earning potential from 2007 to 2018 and the change in workforce distribution metrics from 2003 to 2019 was also examined. The potential role of a pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP was modeled.

Exposures

Lifetime earning potential by subspecialty.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Measures of workforce distribution and fellowship fill rates.

Results

This study included mean compensation data representing 7539 pediatric subspecialists, workforce distribution data representing 24 375 pediatric subspecialists, and fellowship fill rates representing a mean of 1344 pediatric subspecialty fellows per year. Higher lifetime earning potential was associated with shorter distance to subspecialists (−0.59 miles/$100 000 increase in lifetime earning potential; 95% CI, –1.10 to –0.09), higher percentage of hospital referral regions with a subspecialist (+1.17%/$100 000 increase in lifetime earning potential; 95% CI, 0.34-2.00), and higher ratio of subspecialists to regional child population (+0.11 subspecialists/100 000 children/$100 000 increase in lifetime earning potential; 95% CI, 0.04-0.19). The subspecialties for which lifetime earning potential increased the least between 2007 and 2018 experienced the least growth in the ratio of subspecialists to regional child population from 2003 to 2019 (+0.11 subspecialists/100 000 children/$100 000 increase in lifetime earning potential; 95% CI, 0.07-0.16). Higher lifetime earning potential was associated with higher mean fellowship fill rates (+0.96% spots filled/$100 000 increase in lifetime earning potential; 95% CI, 0.15-1.77). Implementing a pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP could increase fellowship fill rates and improve workforce distribution.

Conclusions and Relevance

Lifetime earning potential based on subspecialty may contribute to imbalances in both the current and future pediatric subspecialty workforce. Pediatric subspecialist–specific LRPs, especially for underfilled subspecialties, are potential tools for policy makers to target workforce shortages.

Introduction

We recently published a study analyzing the lifetime financial returns of pediatric subspecialty training.1 We found wide differences in lifetime earning potential between the pediatric subspecialties, differences that have only become more pronounced throughout the last decade.1,2 While there are many factors that go into the decision to subspecialize and trainees may weigh other considerations more highly,3,4,5 the disparate financial returns of fellowship training and subspecialty of choice may influence pediatric workforce distribution if trainees incorporate the economic effect of selecting pediatric subspecialties with lower lifetime earning potential into their career decisions.

There is substantial concern regarding existing workforce shortages within both general pediatrics and multiple pediatric subspecialties.6,7,8 While the number of subspecialists is increasing overall, these gains have not been distributed evenly across the subspecialties or across geographic regions.9,10 If the differences in lifetime earning potential between the subspecialties continue to widen, economic factors may play a role in disrupting the future pediatric workforce and lead to additional unmet needs in pediatric subspecialty care. However, in our prior study,1 we modeled a pediatric subspecialist–specific loan repayment program (LRP) and found that it partially ameliorated the negative financial impact on fellowship training. If there is an association between lifetime earning potential and workforce shortages, an LRP could serve as a targeted intervention to help create a more balanced workforce.

While there are many nonfinancial drivers of workforce distribution, in this study, we examined the association of the lifetime financial returns of subspecialty training and both measures of current workforce distribution and the rates at which graduating pediatric residents chose to pursue training in particular subspecialties. We also modeled the potential role a pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP could play in the decision to subspecialize.

Methods

Data Sources

As summarized in detail in our recent publication,1 we obtained information on fellowship stipends, subspecialty-specific compensation, and educational debt for the academic year of July 2018 to June 2019 from national physician surveys including the Association of American Medical Colleges annual Survey of Resident/Fellow Stipends and Benefits,11 Debt Fact Card,12 and Medical School Faculty Salary Survey.13 Faculty compensation data are presented as mean values aggregated across all survey respondents per subspecialty.

We obtained measures of subspecialty workforce distribution for 2003 and 2019 from publications that reported the mean straight-line distance to subspecialists (in miles), the percent of hospital referral regions (HRRs) with certified subspecialists, and the mean ratio of subspecialists to 100 000 children across HRRs.10,14

We obtained data regarding pediatric subspecialty fellowship fill rate as a percentage of available spots for that subspecialty from 2014 to 2018 from the American Board of Pediatrics.15 We attempted to analyze corresponding years whenever possible; however, we were limited by the availability of our source data and, as a result, the time frames for our data sets did not align perfectly. Because we used publicly available, aggregated, and deidentified data, this study did not meet the criteria for human subject research, and institutional review board review was waived by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Statistical Methods

Using the data sets described above, we estimated age- and academic rank–specific net incomes for pediatric subspecialists throughout a working lifetime and calculated each subspecialty’s lifetime net present value (NPV) in dollars. The NPV is a standard financial technique used to analyze the value of different investments over time,2,16 and we defined the lifetime NPV as the present value of the net income generated from a career in a pediatric subspecialty throughout a working lifetime. The lifetime NPV represents an estimate of the financial returns that a graduating pediatric resident might expect from fellowship training followed by a career as a subspecialist.

We first evaluated the association between the lifetime NPV for 2018 to 2019 and the current distribution of the subspecialty workforce in 2019. Using linear regression analyses (performed in Stata version 15 [StataCorp]), we compared the lifetime NPV for each subspecialty to workforce distribution metrics. To assess the association of changes in the lifetime NPV over time with changes in workforce distribution, we compared the absolute change in the lifetime NPV from 2007 to 20181,2 to the absolute changes in the reported mean straight-line distance to subspecialists, the percent of HRRs with certified subspecialists, and the mean ratio of subspecialists to regional child population from 2003 to 2019.10,14

To evaluate the association of lifetime NPV with the future pediatric workforce, we performed a linear regression analysis on the lifetime NPV of each subspecialty in 2018 and the mean fellowship fill rate as a percentage of available spots for that subspecialty from 2014 to 2018. Because programs may take additional fellows outside the standard fellowship match process, it is possible for a fellowship to have a fill rate of more than 100%. On the other hand, some subspecialties do not fill all their spots. Based on the regression line, we calculated the theoretical lifetime NPV at which a fellowship could expect a 100% fill rate.

Finally, we modeled a pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP, which was recently authorized by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March 2020.17,18 The bill allows for up to $35 000 per year in loan repayment funds for up to 3 years to pediatric subspecialists. This LRP could increase the lifetime NPV for each subspecialty by an estimated $230 541. Using the regression line from the analysis of lifetime NPV and fellowship fill rates, we calculated how many unfilled fellowship spots for each of the undersubscribed subspecialties might be filled per year if subspecialists were able to participate in an LRP.

Results

Our study included mean compensation data representing 7539 pediatric subspecialists, workforce distribution data representing 24 375 pediatric subspecialists, and fellowship fill rates representing a mean of 1344 pediatric subspecialty fellows per year.

The results of the simple bivariate linear regression showed that higher lifetime NPV from 2018 to 2019, seen in subspecialties such as neonatology, critical care, and cardiology, was associated with a shorter mean straight-line distance to be seen by those subspecialists (−0.59 miles/$100 000 increase in lifetime NPV; 95% CI, −1.10 to −0.09; Figure 1A) in 2019. Similarly, a higher lifetime NPV was associated with a higher percentage of HRRs with a certified subspecialist (+1.17%/$100 000 increase in lifetime NPV; 95% CI, 0.34-2.00; Figure 1B), as well as a higher ratio of subspecialists to regional child population (+0.11 subspecialists/100 000 children/$100 000 increase in lifetime NPV; 95% CI, 0.04-0.19; Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Association of Workforce Distribution with Lifetime Earning Potential.

The association between the net present value of lifetime earnings (lifetime net present value [NPV]) across pediatric subspecialties from 2018 to 2019 and measures of workforce distribution in 2019, including distance to the closest pediatric subspecialist, is displayed. The linear regression line is shown with 95% CI shaded in blue.

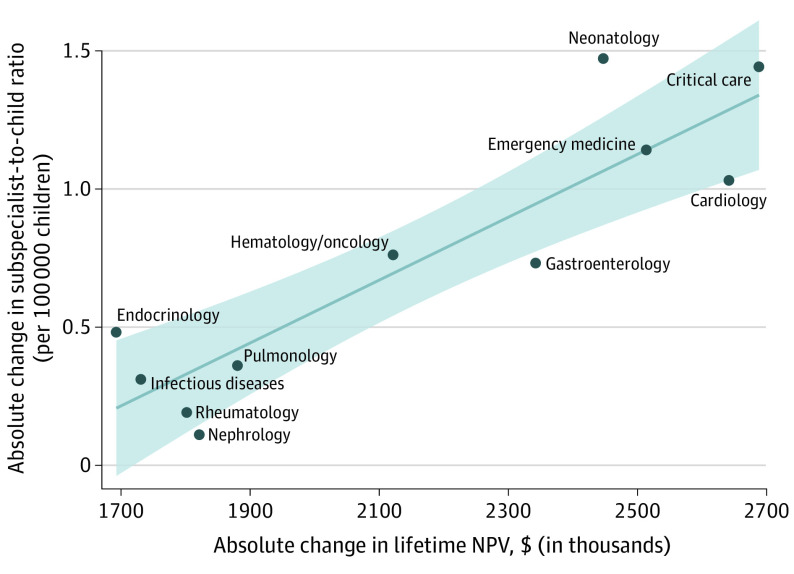

In our repeated measures analysis, higher growth in lifetime NPV from 2007 to 2018 was associated with more growth in the absolute ratio of subspecialists to regional child population between 2003 and 2019 (+0.11 subspecialists/100 000 children/$100 000 increase in lifetime NPV, 95% CI, 0.07-0.16; Figure 2). The least growth was seen in subspecialties with lower lifetime NPV, such as rheumatology, nephrology, and infectious diseases. However, the absolute change in lifetime NPV was not significantly associated with the absolute change in the mean straight-line distance to the closest subspecialist or the absolute change in the percent of HRRs with a subspecialist.

Figure 2. Change in Ratio of Pediatric Subspecialists to Regional Child Population by Lifetime Earning Potential.

The association between the absolute change in the net present value of lifetime earnings (lifetime net present value [NPV]) from 2007 to 2018 and the absolute change in the ratio of pediatric subspecialists to the regional child population from 2003 to 2019 is displayed. The linear regression line is shown with 95% CI shaded in blue.

Higher lifetime NPV from 2018 to 2019 was also associated with higher mean fellowship fill rates between 2014 and 2018 (+0.96% spots filled/$100 000 increase in lifetime NPV; 95% CI, 0.15-1.77; Figure 3). The subspecialties with higher lifetime NPVs, such as neonatology, critical care, and cardiology, overfilled their initially offered fellowship spots, while the subspecialties with lower lifetime NPVs were unable to fill all their fellowship spots offered in the Match. Nephrology, which had one of the lowest lifetime NPVs at $4 286 710, had a final fellowship fill rate of only 65%, while cardiology, which had the highest lifetime NPV of $6 451 752, had a final fellowship fill rate of 106% (the percent is above 100% because more fellows were ultimately taken than initial spots were offered).

Figure 3. Association of Pediatric Subspecialty Fellowship Fill Rates and Lifetime Earning Potential.

The association between the net present value of lifetime earnings (lifetime net present value [NPV]) across pediatric subspecialties from 2018 to 2019 and mean fellowship fill rates from 2014 to 2018 are displayed. The linear regression line is shown with 95% CI shaded in blue.

Based on the linear bivariate regression equation from Figure 3, we calculated that a lifetime NPV of $5 480 820 would yield a 100% fellowship fill rate (95% prediction interval, 74.2%-125.8%). To achieve a 100% fill rate for adolescent medicine, endocrinology, and infectious diseases, the estimated lifetime NPV would have to be increased by more than $1.4 million in each of these subspecialties. We also estimated that for every $104 024 increase in lifetime NPV, we would expect an annual 1% increase in the fill rate (95% CI, 0.16%-1.84%) of a given pediatric subspecialty. Thus, with the proposed pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP raising the lifetime NPV of a subspecialty by an estimated $230 541, we could anticipate a 2.2% increase in the annual fill rate for the underfilling subspecialties if the LRP was fully funded and implemented. This would translate into an additional 1 to 2 fellowship spots filled per year and a 0.1% to 0.3% annual increase in the total workforce for each subspecialty (Table).19

Table. Theoretical Impact of a Pediatric Subspecialist–Specific Loan Repayment Program (LRP)a.

| Subspecialty | Without LRP implementation | With LRP implementation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total certified subspecialists, No. | Fellowship fill rate, No. (%) | Fellowship fill rate, No. (%) | Annual increase in workforce, No. (%) | |

| Adolescent medicine | 501 | 31 (95.5) | 32 (97.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| Endocrinology | 1334 | 84 (96.2) | 86 (98.4) | 2 (0.1) |

| Infectious diseases | 1167 | 59 (85.1) | 61 (87.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Nephrology | 644 | 38 (64.5) | 40 (66.7) | 2 (0.3) |

| Pulmonology | 1073 | 57 (89.2) | 58 (91.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Rheumatology | 387 | 31 (78.7) | 32 (80.9) | 1 (0.3) |

Discussion

We used standard financial techniques to estimate the financial returns of fellowship training and choice of pediatric subspecialty. We evaluated the association of these returns both with current measures of workforce distribution and, by analyzing fellowship fill rates, with potential future workforce shortages. Lifetime earning potential of a subspecialty strongly associated with multiple measures of current workforce distribution, including distance to subspecialists, the availability of subspecialists across referral regions, and the ratio of subspecialists to the regional pediatric population. Our repeated measures analysis revealed that those subspecialties that experienced the least growth in lifelong earning potential also experienced the smallest increase in number of health care professionals normalized by population. Additionally, fellowship training spots for different subspecialties filled at different rates, rates that were associated with the lifetime financial returns of the specific subspecialty. This suggests that perhaps pediatric residents have preferentially pursued fellowships in higher-earning subspecialties.

These findings are corroborated by a recent study using American Board of Pediatrics data regarding fellowship growth rates from 2001 to 2019, which found the highest growth in the number of fellows per year in the pediatric subspecialties of cardiology, critical care, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, and neonatology,9 all of which are subspecialties we found to have a higher lifetime earning potential. The lower earning fields of adolescent medicine, infectious diseases, and nephrology experienced the least growth in the number of fellows per year. Our findings are also in keeping with other markers of workforce shortages, such as wait times for appointments with pediatric subspecialists. According to a recent study, only 17% of pediatric cardiologists reported wait times for new, nonemergent appointments of longer than 2 weeks; on the other hand, 27% of adolescent medicine, 38% of endocrinology, 48% of pulmonology, 52% of rheumatology, and 71% of nephrology subspecialists reported wait times of more than 2 weeks.20

The multiple streams of evidence discussed above suggest a role for economic factors in current and future workforce shortages. Yet, our findings also offer potential targets for policy interventions to ensure a more balanced workforce. Unfilled fellowship spots are not a direct representation of workforce shortages because the process by which fellowship spots are allocated is complicated and depends on a variety of factors, including institution-specific clinical demands, educational and research offerings, and local community rather than national needs. However, one would presume that, if spots are allocated but not filled, hospital systems, training programs, and other stakeholders anticipated current and future needs that are higher than those actually being met.

We previously found that a pediatric subspecialist LRP could help ameliorate the financial returns of pediatric fellowship training.1 Importantly, an LRP is a tool that not only can be targeted to pediatric subspecialists in general, but can also be used to address anticipated workforce shortages in specific subspecialties. While the pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP would not raise the lifetime NPV of many of the subspecialties to the theoretical intercept for a 100% fellowship fill rate, it could increase the number of filled spots for many of the underfilled subspecialties and, for some of these smaller subspecialties, lead to an appreciable increase in the total subspecialist workforce. If a pediatric subspecialist LRP was funded at a level of $50 million per year, it could potentially fund more than 450 participants. An LRP spread out throughout a number of years could have a profound role in pediatric workforce distribution: the 6 subspecialties that did not fill all available fellowship spots comprise a current workforce of 5106 subspecialists; an additional 450 subspecialists would represent an 8.8% increase in the available workforce across these 6 subspecialties. Each additional trained subspecialist could provide decades of care in that related field, affecting thousands of children and their families. However, at the time of this publication, the federal LRP authorized by the CARES Act is still awaiting funding and implementation.

Shortening the length of fellowship training or eliminating medical school tuition, a major component of educational debt, both of which we have shown increase the lifetime NPV of the pediatric subspecialties, are also potential interventions to balance workforce distribution.1 Furthermore, increased salaries for all the pediatric subspecialties can make pediatrics as a field a more attractive career choice as it is one of the lowest-paying areas in all of medicine. Indeed, all programs that specifically increase the lifetime earning potential and salaries for the underfilled subspecialties can help maintain a balanced and adequate workforce.

We also found that the more inpatient-based, procedure-focused subspecialties, such as neonatology, critical care, cardiology, and gastroenterology, had higher lifetime earning potentials, had the most robust workforce, and had overfilled fellowship spots. Conversely, the more outpatient-based, less procedure-focused subspecialties, such as rheumatology, endocrinology, and nephrology, had lower lifetime earning potentials, had the most evidence of current workforce shortages, and had underfilled fellowship spots. This suggests that differences in reimbursements, which help drive physician salaries, may be contributing to a disproportionate increase in the number of higher-paid subspecialists and the failure of lower-earning subspecialties to grow adequately to meet present and future patient care needs. Although beyond the scope of this study, changes in reimbursement patterns, such as the anticipated increase in the valuation of outpatient evaluations and management of Current Procedural Terminology codes, which were scheduled to take effect in January 2021 and are anticipated to increase payment for less procedure-focused subspecialties,21 may represent additional levers that policy makers can use to address workforce shortages. Moreover, efforts to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates to match those paid by Medicare may be another promising avenue for policy intervention given the large proportion of Medicaid patients in many pediatric subspecialists’ payer mix. Understanding the specific ramifications of these changes on salary and pediatric subspecialist workforce distribution will be an important area for future study.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. Our results are dependent on the assumptions made in our referenced data sources as well as the assumptions inherent to our models of lifetime NPV, including those regarding continuity of training, timing of academic promotion, proportion of academic practice per subspecialty, and rates of debt repayment.1 Measures other than those we used may reflect other aspects of workforce distribution and ultimately access to care. The time frames reflected in our data sets do not perfectly align, and our findings theoretically might vary if different time points were chosen. However, we anticipate that the magnitude and direction of the associations would be similar. Additionally, our models cannot capture the many other factors beyond economic concerns that affect the decision to subspecialize, such as lifestyle considerations, research opportunities, and interest in specific diseases or organ systems, which may play a larger role for many trainees than financial considerations.3 For example, gastroenterology demonstrated relatively high fill rates compared with the calculated lifetime NPV, which may reflect some of these other factors: for example, the opportunity to perform well-reimbursed procedures without the typical burden of covering 24/7 inpatient call that the critical care subspecialties bear. Owing to the lack of publicly available data, the present study only includes a subset of the pediatric subspecialties; going forward, it will be important to expand these analyses to include some of the additional subspecialties in which there are significant workforce shortages, such as neurology, allergy/immunology, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, and child and adolescent psychiatry.22,23

Interventions such as the pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP that enhance the financial returns of fellowship training may lead to an increased number of subspecialists but may not lead to the appropriate geographic distribution of those subspecialists. There is a complex interplay in determining where subspecialists choose to practice, as evidenced by regional growth patterns in fellowship size9 and by our repeated measures analysis, which showed that neither the change in distance to the closest subspecialist nor the change in the percent of HRRs with a subspecialist were directly associated with the change in lifetime earning potential. For example, hospital-based subspecialists, such as critical care intensivists, may cluster at tertiary care centers, as opposed to those subspecialists who can practice in ambulatory community settings, such as adolescent medicine clinicians. In addition, an LRP or other financial incentives may lead to unintended consequences, such as physicians pursuing alternative practice patterns such as part-time work.24 Thus, potential policy interventions targeting the subspecialty workforce will need to address factors determining practice location and type. There also has been recent scrutiny on whether perceived subspecialist workforce shortages reflect true unmet care needs or whether adjustments in referral patterns and management practices could address these issues without requiring additional subspecialists.25 Finally, these analyses do not take into account the role that advanced-practice clinicians can play in addressing workforce shortages.

Conclusions

Our results provide evidence that the lifelong financial returns of fellowship training and lifetime earning potential based on subspecialty of choice may contribute to imbalances in both the current and future pediatric workforce. Interventions to improve the lifetime financial return of fellowship training and subspecialty of choice, such as a pediatric subspecialist–specific LRP, particularly for underfilled and underrepresented subspecialties, are potential tools for policy makers to target workforce shortages and imbalances. In addition, increasing the lifelong earning potential of a career in pediatrics can make this field more attractive compared with other areas in medicine. Any future policy changes will need to take into account the complex interplay between the demand for access to care and the distribution and deployment of the physician workforce.

References

- 1.Catenaccio E, Rochlin JM, Simon HK. Differences in lifetime earning potential for pediatric subspecialists. Pediatrics. Published online March 8, 2021. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-027771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochlin JM, Simon HK. Does fellowship pay: what is the long-term financial impact of subspecialty training in pediatrics? Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):254-260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haftel HM. Factors that are priorities in pediatric subspecialty choice. Academic Pediatrics. 2020;20(7):e38-e39. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.06.102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freed GL, Dunham KM, Switalski KE, Jones MD Jr, McGuinness GA; Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics . Recently trained pediatric subspecialists: perspectives on training and scope of practice. Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl 1):S44-S49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1578K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris MC, Marx J, Gallagher PR, Ludwig S. General vs subspecialty pediatrics: factors leading to residents’ career decisions over a 12-year period. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):212-216. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basco WT, Rimsza ME; Committee on Pediatric Workforce; American Academy of Pediatrics . Pediatrician workforce policy statement. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):390-397. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinci RJ. The pediatric workforce: recent data trends, questions and challenges for the future. Pediatrics. Published online March 10, 2021. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-013292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of American Medical Colleges . The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2018 to 2033. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/complexities-physician-supply-and-demand-projections-2018-2033

- 9.Macy ML, Leslie LK, Turner A, Freed GL. Growth and changes in the pediatric medical subspecialty workforce pipeline. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(5):1297-1303. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01311-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner A, Ricketts T, Leslie LK. Comparison of number and geographic distribution of pediatric subspecialists and patient proximity to specialized care in the US between 2003 and 2019. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):852-860. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges . AAMC survey of resident/fellow stipends and benefits. Accessed October 31, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/aamc-survey-resident/fellow-stipends-and-benefits

- 12.Medical Student Education: Debt, Costs, and Loan Repayment Fact Card. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges . AAMC faculty salary report. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/aamc-faculty-salary-report

- 14.Mayer ML. Are we there yet? distance to care and relative supply among pediatric medical subspecialties. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2313-2321. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Board Of Pediatrics . Comparison of ABP data to the NRMP Match data. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.abp.org/content/comparison-abp-data-nrmp-match-data

- 16.Microsoft . NPV function. Accessed July 16, 2020. https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/npv-function-8672cb67-2576-4d07-b67b-ac28acf2a568

- 17.Miller D. Stay in the know: COVID-19 updates from the nation's capital. AAP News. Published May 20, 2020. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/05/20/washington052020

- 18.CARES Act, HR 748, 116th Cong (2019-2020). Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

- 19.American Board Of Pediatrics . Interactive ABP workforce data. Accessed October 31st, 2020. https://www.abp.org/content/data-and-workforce

- 20.Rimsza ME, Ruch-Ross HS, Clemens CJ, Moskowitz WB, Mulvey HJ. Workforce trends and analysis of selected pediatric subspecialties in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(7):805-812. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicare Program; CY 2021 revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other changes to part B payment policies; Medicare shared savings program requirements; Medicaid promoting interoperability program requirements for eligible professionals; establishment of an ambulance data collection system; updates to the quality payment program; Medicare enrollment of opioid treatment programs and enhancements to provider enrollment regulations concerning improper prescribing and patient harm; and amendments to physician self-referral law advisory opinion regulations final rule; and coding and payment for evaluation and management, observation and provision of self-administered esketamine interim final rule. Fed Regist. 2020;85(248):84472-85378.

- 22.Children’s Hospital Association . Pediatric workforce shortages persist. Published January 19, 2018. Accessed October 31, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Issues-and-Advocacy/Graduate-Medical-Education/Fact-Sheets/2018/Pediatric-Workforce-Shortages-Persist

- 23.Bale JF Jr, Currey M, Firth S, Larson R; Executive Committee of the Child Neurology Society . The Child Neurology Workforce Study: pediatrician access and satisfaction. J Pediatr. 2009;154(4):602-606. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller DM, Davis MM, Freed GL. Access to pediatric subspecialty care for children and youth: possible shortages and potential solutions. Pediatr Res. 2020;87(7):1151-1152. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0889-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weyand AC, Freed GL. Pediatric subspecialty workforce: undersupply or over-demand? Pediatr Res. 2020;88(3):369-371. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0766-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]