High rates of mental health and addiction (MHA) disorders are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in adolescents and young adults, 1 the age-group with the highest incidence of MHA disorders. 2,3 The serious human, social, and economic consequences 4 of youth MHA disorders and the inadequacies of the prevailing system of care have been well-documented. 5,6 In response, major systemic transformation has recently been initiated in several countries including Canada 7 with the purpose of setting up an enhanced primary youth mental health (YMH) care system. 8 This development of new YMH services in Canada is being promoted and launched in several jurisdictions as “integrated youth services” (IYS). 9

Researchers in this field have outlined a set of guiding principles and objectives for these initiatives, 10,11 which include focus on early intervention, vocational outcomes, youth participation in designing services, elimination of transition at 18 years, care reflecting the epidemiology of mental health problems, and seamless linkages to services for younger children and older adults. These principles are well supported by different stakeholders, especially youth and families. However, there are currently no evidence-based guidelines for the organization and the nature of integration proposed as part of implementation of these services in Canada. Given the historic inadequacy of services for individuals with MHA disorders, it is imperative that the complex mental health needs of youth with MHA disorders are met in these new YMH services following the principles stated above. In this perspective essay, we address 4 issues that, we argue, should be addressed for any new YMH service to be successful in improving outcome for youth MHA problems:

In the new YMH services, should mental health be the central focus around which nonmental health services are integrated?

Is the new YMH service integrated with the existing primary care (e.g., family physicians) and with specialist services?

Does the current configuration of the new YMH services for youth 12 to 25 years address mental health needs of youth with developmental problems, which have an earlier onset?

Within the context of open access to YMH services to promote early intervention, how should a “case” of YMH disorder be defined?

What Is Meant by IYS and What Is the Focus?

MHA disorders are the leading cause of morbidity and help-seeking in youth. 1 However, the latter often has additional needs in education, housing, employment, and physical and sexual health. Ready access to additional services for these associated needs is one of the several objectives of the new YMH services. However, the term IYS does not stipulate that the additional services are to be integrated around the central focus of mental health. In the absence of any stated requirement for the centrality of mental health and addiction, the new IYS may run the risk of erosion of the capacity for effective mental health care for youth.

While none of the currently active provincial (youthubs.ca, foundrybc.ca, quebec/sante/trouveer-une-resource/aire-ouverte) or national (accessopenminds.ca) initiatives in YMH service in Canada include mental health and substance abuse in their monikers, some either indicate a primary focus on mental health (accessopenminds.ca) or include mental health in the description of their services (youthubs.ca and foundrybc.ca). Other jurisdictions (quebec/sante/trouveer-une-resource/aire-ouverte) have launched IYS without making mental health the focus. Indeed, the term “mental health” does not appear in the list of services offered; however, it is stated that it is possible to receive mental health and physical health service.

If an IYS is promoted as providing global youth services, of which mental health is one, the services may not be able to adequately address the unmet and complex mental health needs of the population. An effective mental health service to be at the core of IYS requires a mental health workforce with specific skills and training to deliver effective care. History is witness to mental health having been chronically under-resourced with regard to programs and skilled multidisciplinary mental health staff including psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and nurse clinicians, and social workers. 12,13 Designing these services as generic youth services and not as primary youth mental health care is in contradiction to epidemiological evidence of MHA disorders (anxiety, depression, substance abuse, attention deficit, eating and psychotic disorders) being the most common health concerns for youth. 3,14 Urgent access to a high-quality assessment of MHA problems and rapid access to appropriate treatment should be the key objectives of the new transformed services. 10,11 These objectives may not be met if mental health and addiction are not the primary focus of these services.

Why Might Mental Health be De-emphasized from IYS?

The tendency to de-emphasize “mental health” from the vocabulary of “IYS” may have several reasons. Removing reference to mental health may be assumed to make these services less stigmatizing and more attractive to youth. Ironically, this may imply that the system of care itself is uncomfortable with the term “mental health,” reflecting a service-based stigma. 15 If true, this would be surprising in the context of the recent explosion of bringing mental health into public discourse (e.g., https://letstalk.bell.ca/en). Hesitation to seek help is less likely related to public stigma and more to self and internalized stigma. 16 There is no evidence that removing emphasis on mental health and making these services generic will make them more attractive to youth. On the contrary, there is evidence that mental health literacy programs, awareness campaigns, and early identification of mental health problems may reduce stigma and contribute to increased help-seeking among youth. 17,18 These questions need to be pursued as part of systematically conducted research on how to make YMH services more attractive.

The de-emphasizing of mental health in “youth services” may also suggest a change in the concept of mental illness and addictions. This may imply a belief that mental illness is like any other medical problem or alternately the consequence of social problems, and, therefore, it does not require a specifically skilled approach. MHA disorders are, in fact, not like any other medical illnesses 19 nor are they merely expressions of social problems. They are products of multiple interacting domains of causation (biological, psychological, social, and cultural) and, therefore, require a highly skilled approach to assessment, case identification, an array of psychological and biological approaches to treatment and facilitating resumption of personal and social functioning. Thus, appropriately addressing youth MHA problems requires, first and foremost, adequately skilled staff from multiple disciplines with expertise specifically in the assessment and treatment of youth MHA disorders. Secondary to this, other services such as employment, housing, physical health and social services must be integrated to the extent that they are readily and rapidly available to support recovery and optimal functioning.

Connecting YMH with Other Primary Care Services and MH Specialist Services

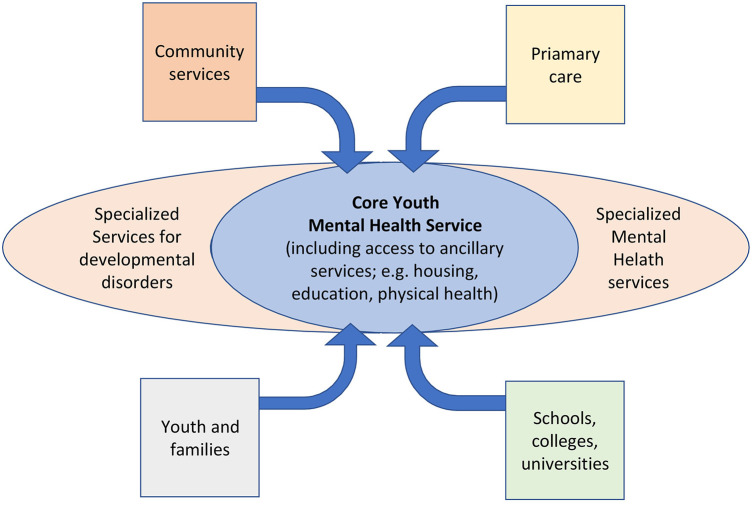

The current YMH initiatives are conceptualized as an enhanced primary mental health care for youth, designed to provide rapid access to assessment, brief mental health interventions to those who are unlikely to require specialist care, access to appropriate additional services (housing, employment, physical health, etc.) and, for patients with greater severity, provide rapid connection to appropriate specialized care (Figure 1). The new YMH services will also need to assure access from current elements of primary health care (e.g., family physicians, pediatricians), in addition to being accessible directly to youth and family without a referral. The new YMH services may continue to have difficulties in rapid access to a higher level of care for those in need, 20 especially in low resource settings. In Canada, with the exception of early psychosis, specialized services for youth with other serious disorders (mood, anxiety, obsessive compulsive, eating, severe personality and substance use disorders) still typically present barriers including long wait times and lack of service integration across the child–adolescent and adult services divide. 21 In order to achieve parity for those with serious mental health problems, the specialized part of the YMH system may need to go through a transformation on the same principles (e.g., early intervention) as those for the new primary YMH care and be integrated with the latter. This is far from having been even attempted. For the 2 components of the system to be able to work efficiently also requires high levels of skill in assessing and treating mild to moderate mental health problems in the new YMH services and to be capable of transferring youth with more serious mental disorders to specialist care with speed and precision. The new YMH services is unlikely to address most or all mental health needs of Canadian youth without integration with the rest of the primary and specialist parts of the system.

Figure 1.

Proposed new youth mental health service configuration.

The 12- to 25-Year Age Limit for YMH Services and the Need to Integrate Access for Those with Early Developmental Disorders

Despite considerable agreement on abolishing the transition of services at 18 years, there are no clear guiding principles on when and how to transition from child psychiatric to the new YMH services, the latter currently configured for youth of 12 to 25 years. Moving the upper limit of transition to 25 years may be justifiable because more than 75% of incidence cases would have appeared by that age, and the transition, if needed, in adulthood may be easier to accomplish than in adolescence. On the other hand, the lower age limit of 12 years may be more problematic, as many child psychiatric disorders, especially developmental disorders (e.g., attention/deficit hyperactivity, pervasive developmental disorders), present much earlier and are often precursors to adult MHA disorders. These children and their families often face very challenging pathways to care for their mental health needs 22 and must have access to the new YMH services at par with those in whom MHA disorders appear de novo. The new YMH services will, therefore, need to integrate primary care–level services for those with developmental psychiatric disorders with the main MHA services, be staffed adequately to serve their immediate needs, and help them navigate the specialist level of care (Figure 1). While some jurisdictions are adopting the age range 0 to 25 for YMH services, 23 this is not the case with the current YMH initiatives in Canada (ACCESS Open Minds, Y-WHO, Foundry, Aires ouvertes). There is much need for further discussion and research in this field in order to improve the structure of these services in line with population needs.

The Importance of Determining the Boundary around “Caseness” for Youth Accessing the New YMH Services

The new YMH services are designed to encourage youth to seek help through open and unencumbered access using multiple portals, including YMH designated spaces, without a referral, 24 in addition to referrals from within the primary health care and the education systems. While it is essential to remove obstacles for help-seeking, the responsibility for evaluation of caseness of the presenting mental health problem and subsequent decisions for intervention(s) and/or referral to a specialized service falls on the assessing clinician, usually a nonpsychiatrist. Establishing caseness may be more difficult in the case of youth seeking help for the first time for an undefined mental health problem compared to delineating one established MHA disorder from another (e.g. psychotic vs. nonpsychotic disorder). Further, using a psychiatric diagnosis at first assessment may be neither possible nor advisable, given the sensitivity of labeling without adequate evidence. Caseness in such circumstances may be primarily based on the level and source of distress and impaired functioning, and an assessing clinician will need to possess adequate expertise in mental health. The boundary between variations of normal behavior (e.g., crisis following a relationship breakup) and that associated with an MHA disorder may indeed be difficult to define. Assessing clinicians at the first point of contact will need to be aware of negative consequences of unnecessary treatment, including possible harm from therapeutic interventions, 25,26 interference with personal resilience and agency, and the potential impact of such labeling on future help-seeking for health services. On the other hand, missing the presence of an MHA disorder is likely to have consequences such as failed opportunity for early intervention, likelihood of utilizing institutional services in future, and self-harm. Improving the rate of correct assignment of caseness without resorting to making early psychiatric diagnosis will require further research. This could involve validating routine use of brief self-administered instruments to assess the nature and severity of distress (e.g., Kessler 10-item Distress Scale), 27 supported by use of a clinical assessment scale (e.g., Clinical Global Impression–modified), 28 a functioning scale (e.g., Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale) 29 in the context of a clinical interview. Such a multidimensional assessment, 30 once validated, would allow an assessing clinician (nonpsychiatrist) to make decisions regarding need for further specialist diagnostic assessment and care without using a diagnostic label early in the course of the service encounter. This further supports the argument for a high level of skill in mental health for staff working in the new YMH services and integration of a population-level approach to identifying new cases.

Conclusions

We support the continued development of the new YMH services to be purposed as an “enhanced primary mental health care” providing rapid access to a skilled assessment of MHA problems, brief interventions when appropriate, supportive services (e.g. housing, physical health, employment), and rapid access to specialized care, when needed. However, several key issues may need to be addressed in the process of scaling up current models of service across the country. We propose that the new YMH services be specifically focused around MHA disorders through integration at several levels: ancillary services be organized around the primary focus of assessment and treatment of YMHA disorders and not by making mental health as just one part of a host of other services, thereby, making them Integrated Youth Mental Health Services and not just Integrated Youth Services; the new YMH services be integrated with other primary health care (e.g. family physicians) and specialist services for care of serious MHA disorders; particular attention be paid to integrate needs of younger children (under 12) and youth with developmental disorders; to explore the potential benefit of removing the lower end of the age criterion (12 years); and the issue of caseness of a YMH disorder be established, through systematic research, to reduce the risk of false positives and false negatives. We strongly propose that a clearly articulated national research plan be developed to establish an evidence base that would ensure fidelity to the well-established principles and objectives of YMH service. 10 Evaluation of whether the current YMH initiatives are meeting their objectives will assist in supporting large-scale deployment of one or more models of YMH services. While an uncontrolled multi-site evaluation of one of the models of YMH service transformation is nearing completion, 30 controlled evaluation of effectiveness of one or more models, using their current infrastructure, may further strengthen the scalability of the new YMH services. In order to match the current enthusiasm generated for improving YMH service delivery, it is important that this first step in YMH service reform be adequately structured, resourced, and investigated for effectiveness, followed by similar development in specialist services as a continuum. Otherwise, we will once again run the risk of creating the same disappointing state of failed reforms that litter the history of treatment of mental illness.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AM has no competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript. Unrelated to the work in the manuscript, AM has received funding for research consultations and honoraria for lectures delivered at conferences sponsored by Lundbeck and Otsuka, Canada and Global. PB has no competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript. RJ has no competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript. Unrelated to the work in the manuscript, RJ has participated in advisory boards for Pfizer, Janssen, BMS, Sunovion, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Perdue, and Myelin. He received grant funding from them and from Astra Zeneca and HLS. He received honoraria from Janssen Canada, Shire, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer and from Perdue for CME presentations and royalties for the Henry Stewart talk.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AM is funded through the Canada Research Chairs program.

References

- 1. Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2383–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(s54):s5–s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cosgrave EM, Yung AR, Killackey EJ, et al. Met and unmet need in youth mental health. J Mental Health. 2008;17(6):618–628. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malla A, Shah J, Iyer S. Youth mental health should be a top priority for health care in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(4):216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: best available evidence and future directions. Med J Australia. 2017;207(S10):S5–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rickwood D, Paraskakis M, Quin D, et al. Australia’s innovation in youth mental health care: the headspace centre model. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(1):159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halsall T, Manion I, Iyer SN, Mathias S, Purcell R, Henderson J. Trends in mental health system transformation: integrating youth services within the Canadian context. Los Angeles (CA). Sage; 2019. p. 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(s54):s30–s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malla A, Iyer S, Shah J, et al. Canadian response to need for transformation of youth mental health services: ACCESS Open Minds (Esprits ouverts). Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carbone S, Rickwood D, Tanti C. Workforce shortages and their impact on Australian youth mental health service reform. Adv Mental Health. 2011;10(1):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone S, Amminger GP. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(4):301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henderson C, Noblett J, Parke H, et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(6):467–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, Schultze-Lutter F. Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milin R, Kutcher S, Lewis SP, et al. Impact of a mental health curriculum on knowledge and stigma among high school students: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(5):383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Booth RG, Allen BN, Jenkyn KMB, Li L, Shariff SZ. Youth mental health services utilization rates after a large-scale social media campaign: population-based interrupted time-series analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2018;5(2):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malla A, Joober R, Garcia A. Mental illness is like any other medical illness: a critical examination of the statement and its impact on patient care and society. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40(3):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McGorry P, Trethowan J, Rickwood D. Creating headspace for integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reid GJ, Brown JB. Money, case complexity, and wait lists: perspectives on problems and solutions at children’s mental health centers in Ontario. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2008;35(3):334–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh SP, Paul M, Ford T, et al. Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: multiperspective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vyas NS, Birchwood M, Singh SP. Youth services: meeting the mental health needs of adolescents. Irish J Psychol Med. 2015;32(1):13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Settipani CA, Hawke LD, Cleverley K, et al. Key attributes of integrated community-based youth service hubs for mental health: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crawford MJ, Thana L, Farquharson L, et al. Patient experience of negative effects of psychological treatment: results of a national survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(3):260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Linden M, Schermuly-Haupt ML. Definition, assessment and rate of psychotherapy side effects. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berk M, Ng F, Dodd S. The validity of the CGI severity and improvement scales as measures of clinical effectiveness suitable for routine clinical use. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(6):979–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rybarczyk B. Social and occupational functioning assessment scale (SOFAS). In: Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. 1st ed. Vol. LXIII. New York (NY). Springer; 2011. p. 2313. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iyer SN, Shah J, Boksa P, et al. A minimum evaluation protocol and stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial of ACCESS Open Minds, a large Canadian youth mental health services transformation project. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]