Key Points

Question

Have specific opioid prescribing practices for children, adolescents, and younger adults in the US changed from 2006 to 2018?

Findings

In this cross-sectional analysis of US opioid prescription data, opioid dispensing rates have decreased significantly for children, adolescents, and younger adults since 2013. Overall, rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions decreased for adolescents and young adults but increased in young children.

Meaning

Findings of this study suggest that total opioid prescriptions have decreased in patients younger than 25 years, but opioids remain commonly dispensed; further investigation into specific opioid prescribing practices may inform targeted interventions to ensure appropriate opioid prescribing in this subset of the US population.

Abstract

Importance

Prescription opioids are involved in more than half of opioid overdoses among younger persons. Understanding opioid prescribing practices is essential for developing appropriate interventions for this population.

Objective

To examine temporal trends in opioid prescribing practices in children, adolescents, and younger adults in the US from 2006 to 2018.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A population-based, cross-sectional analysis of opioid prescription data was conducted from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2018. Longitudinal data on retail pharmacy–dispensed opioids for patients younger than 25 years were used in the analysis. Data analysis was performed from December 26, 2019, to July 8, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Opioid dispensing rate, mean amount of opioid dispensed in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day (individuals aged 15-24 years) or MME per kilogram per day (age <15 years), duration of prescription (mean, short [≤3 days], and long [≥30 days] duration), high-dosage prescriptions, and extended-release or long-acting (ER/LA) formulation prescriptions. Outcomes were calculated for age groups: 0 to 5, 6 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and 20 to 24 years. Joinpoint regression was used to examine opioid prescribing trends.

Results

From 2006 to 2018, the opioid dispensing rate for patients younger than 25 years decreased from 14.28 to 6.45, with an annual decrease of 15.15% (95% CI, −17.26% to −12.99%) from 2013 to 2018. The mean amount of opioids dispensed and rates of short-duration and high-dosage prescriptions decreased for all age groups older than 5 years, with the largest decreases in individuals aged 15 to 24 years. Mean duration per prescription increased initially for all ages, but then decreased for individuals aged 10 years or older. The duration remained longer than 5 days across all ages. The rate of long-duration prescriptions increased for all age groups younger than 15 years and initially increased, but then decreased after 2014 for individuals aged 15 to 24 years. For children aged 0 to 5 years dispensed an opioid, annual increases from 2011 to 2014 were noted for the mean amount of opioids dispensed (annual percent change [APC], 10.58%; 95% CI, 1.77% to 20.16%) and rates of long-duration (APC, 30.42%; 95% CI, 14.13% to 49.03%), high-dosage (APC, 31.27%; 95% CI, 16.81% to 47.53%), and ER/LA formulation (APC, 27.86%; 95% CI, 12.04% to 45.91%) prescriptions, although the mean amount dispensed and rate of high-dosage prescriptions decreased from 2014 to 2018.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that opioid dispensing rates decreased for patients younger than 25 years, with decreasing rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions for adolescents and younger adults. However, opioids remain readily dispensed, and possible high-risk prescribing practices appear to be common, especially in younger children.

This cross-sectional study examines the rates of opioid prescribing and duration of those prescriptions in children, adolescents, and younger adults from 2006 to 2018.

Introduction

The rate of opioid overdose deaths continues to increase in the US, with opioids implicated in the majority of pediatric and younger adult drug overdose deaths.1,2,3 Prescription opioids are involved in more than half of opioid overdose deaths in the pediatric population.4,5,6 Prescription opioid use in children and adolescents is associated with a risk for future opioid misuse, opioid-related adverse events, and emergency department visits or hospitalizations for unintentional opioid exposures by younger children.7,8,9,10,11,12,13

There is an increased risk of opioid misuse and overdose when adults are prescribed higher-dosage, longer-duration, and extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) formulation opioid prescriptions.14,15,16,17 Two studies investigating opioid prescribing patterns and the risk of overdose in adolescents and younger adults revealed similar findings, emphasizing the need for further research characterizing opioid prescribing practices in this population.18,19 Although temporal trends in these high-risk opioid prescribing practices have been described in the general population,20,21 to our knowledge, there are no similar studies in youths. The limited research in children and adolescents has focused on trends in opioid prescribing rates, reporting decreases in prescribing rates similar to those in adults.20,21,22,23 One study in adolescents assessed trends in prescription duration, showing a decrease in short-duration prescriptions.24 However, to our knowledge, no US population-based studies have provided a comprehensive look at trends in opioid prescribing practices, including amount prescribed, duration, high-dosage, and ER/LA prescriptions, in the pediatric, adolescent, and younger adult populations.

Although some states have enacted regulations on opioid prescribing for children and postoperative guidelines for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents were recently released, there remain no national guidelines regarding general opioid prescribing for children and adolescents.25,26 To understand the current state of the opioid epidemic in youths, it is necessary to not only describe the most recent trends in opioid dispensing rates, but also examine trends in specific opioid prescribing practices by age, including amount dispensed, prescription duration, and high-dosage and ER/LA prescriptions. Improved knowledge of these prescribing practices and possible high-risk prescribing will inform targeted areas for future study and interventions to ensure safe and appropriate opioid prescribing within this population. In this study, we aimed to estimate temporal trends and the magnitude of change in several key opioid prescribing practices in children, adolescents, and younger adults in the US from 2006 to 2018.

Methods

Data Sources

We abstracted data from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2018, from IQVIA Longitudinal Prescription Data (LRx), a nationwide database of all-payer opioid prescriptions dispensed from US outpatient retail pharmacies.27 From 2006 to 2018, the database captured 74% to 92% of US retail outpatient opioid prescriptions. Data on prescriptions obtained by mail order, those dispensed in long-term care facilities, cough/cold formulations, and methadone/buprenorphine used to treat opioid use disorder were not included. Data were restricted to prescriptions dispensed to patients aged 0 to 24 years. Data analysis was conducted from December 26, 2019, to July 8, 2020.

According to the institutional policy of New York University Grossman School of Medicine, this study did not involve human subjects and so did not require institutional review board review. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

We obtained annual population data from the US Census Bureau American FactFinder 2006-2018 1-year estimates to calculate age-adjusted prescribing rates.28 The IQVIA LRx database does not include data on individuals’ weight, so we estimated weights using the median weight in kilograms from age- and sex-specific growth charts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.9,19,29 This estimated weight was used to calculate morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (a value assigned to each opioid formulation representing analgesic potency relative to morphine) per kilogram per day in patients younger than 15 years.

Variables

Based on the age provided with each opioid prescription, we created 5 groups: 0 to 5 years, 6 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, 15 to 19 years, and 20 to 24 years. Prescribing practice variables were calculated annually for each age group and included (1) opioid dispensing rates (number of dispensed opioid prescriptions per 100 persons); (2) mean amount of opioid dispensed per prescription, calculated using MME and using prescription duration,30 with weight-based dosing (morphine milligram equivalents per kilogram per day) for patients younger than 15 years; (3) duration of opioid prescription (days’ supply per prescription), including mean, short (≤3 days), and long (≥30 days) duration21,31; (4) high-dosage opioid prescription (≥90 MME/d for individuals aged 15-24 years14,18,31; >2 MME/kg/d for <15 years, defined using weight-based dosing above the maximum recommended prescribed daily dose from pharmaceutical formularies32,33,34); and (5) ER/LA formulation prescriptions.35

Rates for short-duration, long-duration, high-dosage, and ER/LA prescriptions were calculated per 100 persons dispensed an opioid in that year and age group. Because prescribing practice variables were analyzed at the prescription level, we also calculated the number of patients dispensed 1 vs multiple prescriptions to determine the extent to which prescribing trends could have been related to a minority of patients.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were completed using R, version 3.6.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing).36 Joinpoint regression program analyses were used to identify the best-fitting points (years) with a statistically significant increase or decrease in opioid prescribing trends from 2006 to 2018 for each variable and age group.37,38,39

Owing to the increase in retail outpatient pharmacy channel coverage in the IQVIA LRx database from 2013 to 2014, a joinpoint jump model was used to avoid the bias associated with a standard joinpoint model; 2014 was an added parameter to the model as a jump trend.38 We fit a weighted least-squares regression model with constant variance and a log transformation. A maximum of 2 joinpoints were searched for using the grid search algorithm.

Final models were selected using a Monte Carlo permutation test to determine the optimal number of joinpoints (α = .05). We report the annual percent change (APC) with 95% CIs for each trend line segment. The average annual percent changes (AAPCs) with 95% CIs are reported for the complete time period (2006-2018). Findings were statistically significant at P < .05, using a 2-sided test based on the permutation methods.

The IQVIA LRx database does not contain prescription diagnoses or indications but includes prescriber specialty information. To identify patients who may be dispensed opioids based on different practice guidelines than those for the general population, we performed 2 sensitivity analyses. For the first, we removed prescriptions from clinicians in oncology, hematology, and hospice subspecialties. For the second, we removed prescriptions that were both high dosage and long duration or patients dispensed both a high-dosage prescription and a long-duration prescription.

Results

Overall Trends

From 2006 to 2018, total US annual opioid prescriptions dispensed to patients younger than 25 years was highest in 2007 at 15 689 779 prescriptions, and since 2012 has steadily decreased to 6 705 478 in 2018 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Most opioid prescriptions (80.4%) were dispensed for patients aged 15 to 24 years. During each year, most patients (72%-82%) were dispensed only 1 opioid prescription (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The total opioid dispensing rate per 100 persons for patients younger than 25 years decreased from 14.28 in 2006 to 6.45 in 2018, with an annual decrease of 15.15% (95% CI, −17.26% to −12.99%) from 2013 to 2018. There were significant decreases in dispensing rates for every age group from 2014 to 2018 (Figure 1A, Table 1).

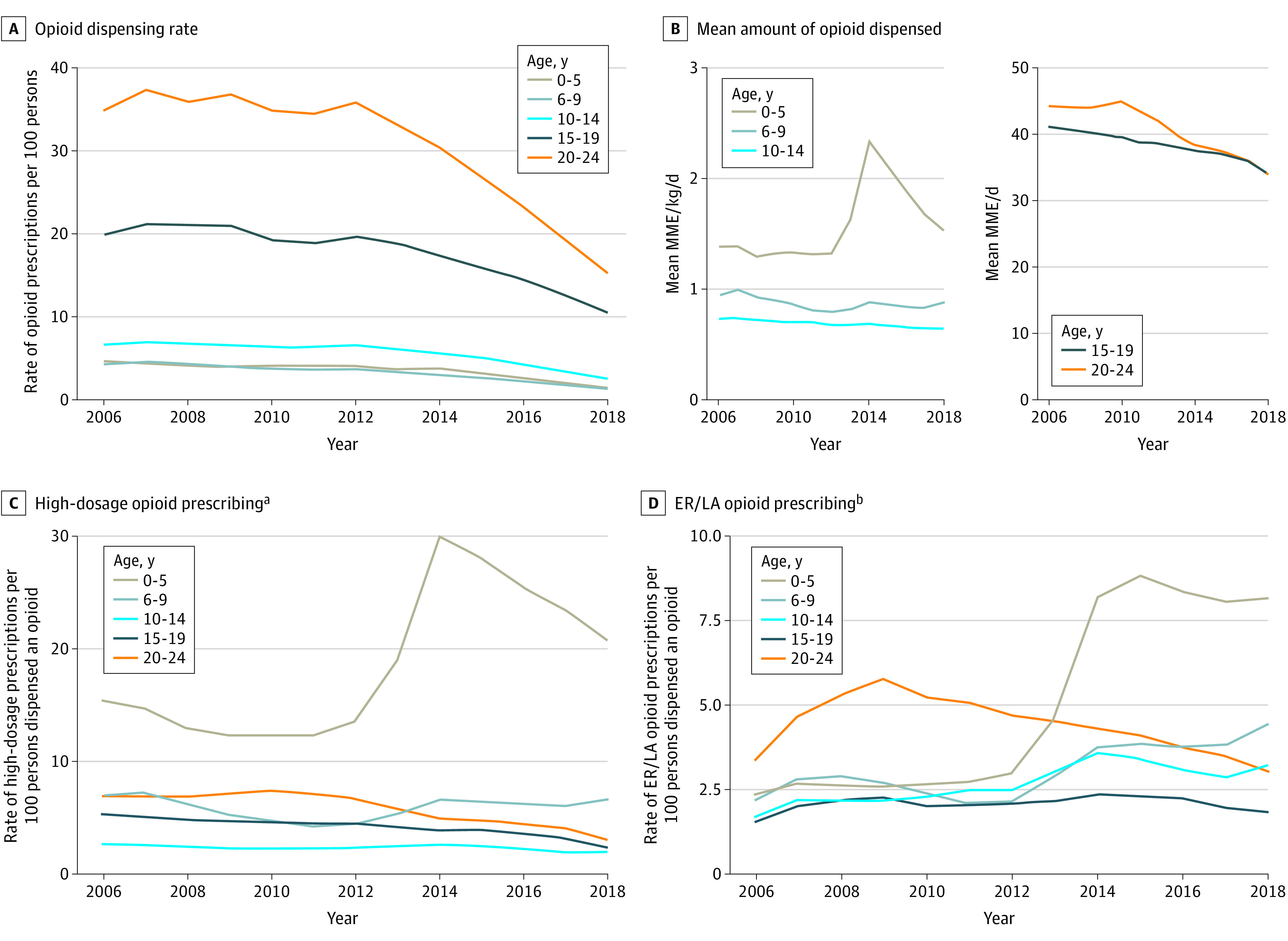

Figure 1. Annual Opioid Prescribing Practices in the US, 2006-2018.

Opioid prescribing practices shown by dispensing rate (A), mean amount dispensed (B), high-dosage prescribing (C), and ER/LA prescribing (D).

aHigh dosage defined as greater than 2 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/kg/d for individuals younger than 15 year and greater than 90 MME/d for those aged 15 to 24 years.

bExtended-release or long-acting opioid formulation.

Table 1. Trends in Opioid Dispensing Rates per 100 Persons and Mean Amount of Opioid Dispensed, 2006-2018.

| Dispensing rate | Mean or rate | AAPC (95% CI)a | APC and joinpoint segmentsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2018 | 2006-2013 | 2014-2018 | Trend years | APC (95% CI) | |

| Opioid dispensing rate, per 100 persons | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 14.28 | 6.45 | −1.03 (−2.51 to 0.46) | −15.15 (−17.26 to −12.99)b | 2006-2013 | −1.03 (−2.51 to 0.46) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2018 | −15.15 (−17.26 to −12.99)b | |

| 0-5 | 4.64 | 1.47 | −2.42 (−4.01 to −0.81)b | −21.14 (−26.18 to −15.74)b | 2006-2013 | −2.42 (−4.01 to −0.81)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2016 | −16.40 (−26.05 to −5.49)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −25.60 (−34.19 to −15.90)b | |

| 6-9 | 4.30 | 1.43 | −3.75 (−4.84 to −2.64)b | −16.33 (−19.61 to −12.91)b | 2006-2015 | −3.75 (−4.84 to −2.64)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2015-2018 | −20.15 (−24.99 to −14.99)b | |

| 10-14 | 6.63 | 2.64 | −1.24 (−2.49 to 0.03) | −17.09 (−21.25 to −12.71)b | 2006-2013 | −1.24 (−2.49 to 0.03) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2016 | −11.60 (−19.65 to −2.74)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −22.24 (−29.32 to −14.45)b | |

| 15-19 | 19.87 | 10.54 | −1.47 (−2.60 to −0.32)b | −10.77 (−14.30 to −7.09)b | 2006-2015 | −1.47 (−2.60 to −0.32)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2015-2018 | −13.67 (−18.97 to −8.03)b | |

| 20-24 | 34.81 | 15.24 | −0.94 (−2.43 to 0.57) | −15.67 (−17.78 to −13.50)b | 2006-2013 | −0.94 (−2.43 to 0.57) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2018 | −15.67 (−17.78 to −13.50)b | |

| Mean amount opioid dispensed, MME/kg/d or MME/d c | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| 0-5 | 1.39 | 1.54 | 1.79 (−0.30 to 3.92) | −10.14 (−12.47 to −7.75)b | 2006-2011 | −1.53 (−3.34 to 0.32) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2014 | 10.58 (1.77 to 20.16)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −10.14 (−12.47 to −7.75)b | |

| 6-9 | 0.95 | 0.89 | −2.38 (−3.21 to −1.54)b | −2.38 (−3.21 to −1.54)b | NAd | NAd |

| 10-14 | 0.74 | 0.66 | −1.26 (−1.43 to −1.08)b | −1.26 (−1.43 to −1.08)b | NAd | NAd |

| 15-19 | 41.21 | 33.90 | −1.16 (−1.25 to −1.06)b | −2.51 (−3.03 to −1.98)b | 2006-2016 | −1.16 (−1.25 to −1.06)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −3.83 (−5.05 to −2.61)b | |

| 20-24 | 44.30 | 34.02 | −1.20 (−1.74 to −0.65)b | −3.14 (−3.50 to −2.77)b | 2006-2010 | 0.28 (−0.81 to 1.39) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2010-2018 | −3.14 (−3.50 to −2.77)b | |

Abbreviations: AAPC, average annual percent change; APC, annual percent change; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; NA, not applicable.

Joinpoint allowed up to 2 joinpoints. Owing to retail channel data coverage, 2014 was added as a jump point.

Annual percent change and AAPC were statistically significant (P < .05) using a 2-sided test based on the permutation methods.

Mean morphine milligram equivalents per kilogram per day per prescription for persons younger than 15 years and mean morphine milligram equivalents per day per prescription for persons aged 15 to 24 years. Trends not reported for total strata (<25 years) because mean morphine milligram equivalent amounts are not comparable throughout all age groups.

No joinpoint detected for these strata and outcomes; APC was constant and equal to AAPC.

During the study period, the mean amount of opioids dispensed decreased for all age groups, except for children aged 0 to 5 years, for whom amounts initially increased, followed by a decrease toward the end of the study period (Figure 1B). Rates of high-dosage prescriptions decreased for all age groups older than 5 years, with the largest decreases in those aged 15 to 24 years (Figure 1C). Rates of ER/LA prescriptions had varied trends by age group, with a marked increase for children aged 0 to 5 years and an initial increase followed by a decrease for individuals aged 20 to 24 years (Figure 1D). Mean prescription duration increased for all age groups initially, but then decreased for those aged 10 years or older (Figure 2A). Rates of short-duration prescriptions decreased in all age groups, except for children aged 0 to 5 years (Figure 2B). Rates of long-duration prescriptions increased during the study period for children younger than 15 years; for those aged 15 to 24 years, rates initially increased, followed by a larger decrease (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Annual Duration of Opioid Prescriptions in the US, 2006-2018.

Duration of opioid therapy shown as mean (A), short term (≤3 days) (B), and long term (≥30 days) (C).

Opioid Prescribing Practices by Age Group

Dispensing rates for children aged 0 to 5 years decreased from 4.64 in 2006 to 1.47 by 2018; the largest annual decrease (APC, −25.60%; 95% CI, −34.19% to −15.90%) occurred in 2016-2018 (Table 1). The mean amount dispensed (APC, 10.58%; 95% CI, 1.77% to 20.16%) and rates of long-duration (APC, 30.42%; 95% CI, 14.13% to 49.03%), high-dosage (APC, 31.27%; 95% CI, 16.81% to 47.53%), and ER/LA (APC, 27.86%; 95% CI, 12.04% to 45.91%) prescriptions increased from 2011 to 2014, although the mean amount dispensed (APC, −10.14%; 95% CI, −12.47% to −7.75%) and the rate of high-dosage prescriptions (APC, −9.92%; 95% CI, −13.19% to −6.53%) then decreased from 2014 to 2018 (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3). The mean prescription duration increased from 8.12 to 11.22 days. There was no significant change in short-duration prescriptions. During the study period, of all opioids dispensed, long-duration prescriptions increased from 7.3% to 19.9%, high-dosage prescriptions increased from 15.5% to 20.8%, and ER/LA prescriptions increased from 1.8% to 5.3% (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Trends in Duration of Opioid Prescriptions per 100 Persons Dispensed an Opioid 2006-2018.

| Prescribing characteristic | Mean or rate | AAPC (95% CI)a | APC and joinpoint segmentsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2018 | 2006-2013 | 2014-2018 | Trend Years | APC (95% CI) | |

| Mean duration per prescription, d | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 6.08 | 6.24 | 1.97 (1.60 to 2.35)b | −3.02 (−4.26 to −1.76)b | 2006-2015 | 1.97 (1.60 to 2.35)b |

| 2015-2018 | −4.63 (−6.54 to −2.68)b | |||||

| 0-5 | 8.12 | 11.22 | 2.51 (1.65 to 3.39)b | 0.39 (−1.16 to 1.98) | 2006-2011 | 1.13 (−0.03 to 2.31) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2015 | 6.05 (3.34 to 8.84)b | |

| 2015-2018 | −1.42 (−3.95 to 1.17) | |||||

| 6-9 | 7.27 | 9.19 | 0.86 (0.28 to 1.44)b | 0.86 (0.28 to 1.44)b | NAc | NAc |

| 10-14 | 5.91 | 7.38 | 3.38 (2.18 to 4.59)b | −1.97 (−3.64 to −0.26)b | 2006-2009 | 1.20 (−1.52 to 4.00) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2009-2014 | 5.04 (3.24 to 6.87)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −1.97 (−3.64 to −0.26)b | |

| 15-19 | 5.11 | 5.09 | 1.16 (0.94 to 1.38)b | −2.86 (−4.01 to −1.69)b | 2006-2016 | 1.16 (0.94 to 1.38)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −6.72 (−9.29 to −4.07)b | |

| 20-24 | 6.28 | 6.15 | 2.03 (1.56 to 2.51)b | −3.80 (−4.92 to −2.67)b | 2006-2010 | 4.35 (3.36 to 5.34)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2010-2016 | −0.98 (−1.64 to −0.31)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −6.54 (−9.30 to −3.70)b | |

| Short duration (≤3 d) | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 76.34 | 63.83 | −1.38 (−1.88 to −0.88)b | −1.04 (−3.05 to 1.02) | 2006-2013 | −1.38 (−1.88 to −0.88)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2016 | −5.06 (−8.62 to −1.37)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | 3.16 (−0.70 to 7.77) | |

| 0-5 | 36.78 | 45.05 | −1.20 (−2.65 to 0.27) | 4.50 (−3.62 to 13.30) | 2006-2016 | −1.20 (−2.65 to 0.27) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | 10.53 (−8.57 to 33.61) | |

| 6-9 | 47.36 | 42.70 | −2.20 (−2.68 to −1.72)b | 1.33 (−1.35 to 4.07) | 2006-2016 | −2.20 (−2.68 to −1.72)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | 4.98 (−1.41 to 11.78) | |

| 10-14 | 65.06 | 54.41 | −2.51 (−2.79 to −2.24)b | 0.84 (−0.72 to 2.43) | 2006-2016 | −2.51 (−2.79 to −2.24)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | 4.32 (0.56 to 8.22)b | |

| 15-19 | 78.52 | 63.47 | −2.08 (−2.51 to −1.65)b | −0.51 (−2.00 to 1.01) | 2006-2012 | −1.51 (−2.10 to −0.92)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2012-2016 | −5.40 (−7.07 to −3.71)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | 4.64 (0.99 to 8.42)b | |

| 20-24 | 89.69 | 69.37 | −1.28 (−2.70 to 0.15) | −2.57 (−3.25 to −1.88)b | 2006-2009 | 0.45 (−3.35 to 4.40) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2009-2018 | −2.57 (−3.25 to −1.88)b | |

| Long duration (≥30 d) | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 8.15 | 8.78 | 5.75 (3.78 to 7.76)b | −9.50 (−11.98 to −6.94)b | 2006-2009 | 10.43 (5.68 to 15.40)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2009-2014 | 2.37 (−0.44 to 5.26) | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −9.50 (−11.98 to −6.94)b | |

| 0-5 | 9.66 | 30.55 | 8.03 (4.50 to 11.69)b | 1.75 (−2.46 to 6.13) | 2006-2011 | 0.20 (−2.75 to 3.23) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2014 | 30.42 (14.13 to 49.03)b | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | 1.75 (−2.46 to 6.13) | |

| 6-9 | 9.08 | 17.84 | 0.01 (−3.61 to 3.76) | 7.77 (4.04 to 11.64)b | 2006-2011 | −2.94 (−8.50 to 2.96) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2018 | 7.77 (4.04 to 11.64)b | |

| 10-14 | 6.51 | 12.07 | 8.01 (4.05 to 12.13)b | −3.25 (−9.11 to 3.00) | 2006-2013 | 8.01 (4.05 to 12.13)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2018 | −3.25 (−9.11 to 3.00) | |

| 15-19 | 4.53 | 4.26 | 2.95 (1.58 to 4.35)b | −9.20 (−12.67 to −5.58)b | 2006-2014 | 2.95 (1.58 to 4.35)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −9.20 (−12.67 to −5.58)b | |

| 20-24 | 10.80 | 9.11 | 5.60 (1.10 to 10.30)b | −12.50 (−14.87 to −10.06)b | 2006-2010 | 13.64 (9.31 to 18.14)b |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2010-2013 | −4.25 (−15.31 to 8.27) | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2013-2018 | −12.50 (−14.87 to −10.06)b | |

Abbreviations: AAPC, average annual percent change; APC, annual percent change; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; NA, not applicable.

Joinpoint allowed up to 2 joinpoints. Owing to retail channel data coverage, 2014 was added as a jump point.

Annual percent change and AAPC were statistically significant (P < .05) using a 2-sided test based on the permutation methods.

No joinpoint detected for this strata and outcome. APC was constant and equal to AAPC.

Table 3. Trends in Rate of High-Dosage Opioid Prescriptions and Rate of ER/LA Formulation Prescriptions per 100 Persons Dispensed an Opioid, 2006-2018.

| Prescription type | Mean or rate | AAPC (95% CI)a | APC and joinpoint segmentsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2018 | 2006-2013 | 2014-2018 | Trend years | APC (95% CI) | |

| High-dosage prescription, rate per 100 persons dispensed an opioid b | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 10.80 | 5.03 | −2.24 (−3.53 to −0.93)c | −14.85 (−18.68 to −10.48)c | 2006-2012 | −0.94 (−2.73 to 0.88) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2012-2016 | −9.68 (−14.43 to −4.67)c | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −19.72 (−27.94 to −10.57)c | |

| 0-5 | 20.51 | 31.92 | 3.68 (0.70 to 6.75)c | −9.92 (−13.19 to −6.53)c | 2006-2011 | −5.66 (−8.09 to −3.16)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2014 | 31.27 (16.81 to 47.53)c | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −9.92 (−13.19 to −6.53)c | |

| 6-9 | 9.60 | 9.01 | −5.52 (−11.24 to 0.57) | −0.89 (−8.42 to 7.27) | 2006-2011 | −11.78 (−16.58 to −6.71)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2014 | 12.14 (−12.67 to 44.00) | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −0.89 (−8.42 to 7.27) | |

| 10-14 | 3.70 | 2.61 | −1.31 (−4.44 to 1.93) | −9.67 (−13.88 to −5.26)c | 2006-2009 | −5.23 (−12.11 to 2.20) |

| NA | NA | 2009-2014 | 1.73 (−3.01 to 6.71) | |||

| NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −9.67 (−13.88 to −5.26)c | |||

| 15-19 | 8.11 | 2.94 | −3.45 (−4.26 to −2.64)c | −14.37 (−18.22 to −10.35)c | 2006-2016 | −3.45 (−4.26 to −2.64)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −24.06 (−31.81 to −15.42)c | |

| 20-24 | 13.02 | 4.56 | −1.80 (−3.60 to 0.02) | −15.39 (−19.20 to −11.39)c | 2006-2010 | 4.45 (0.62 to 8.43)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2010-2016 | −9.57 (−11.93 to −7.15)c | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −20.83 (−29.65 to −10.89)c | |

| ER/LA prescription, rate per 100 persons dispensed an opioid d | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| Total <25 | 2.43 | 2.89 | 4.45 (0.08 to 9.01)c | −6.55 (−11.29 to −1.56)c | 2006-2008 | 21.89 (1.72 to 46.05)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2008-2015 | −1.81 (−4.76 to 1.24) | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2015-2018 | −8.08 (−16.03 to 0.62) | |

| 0-5 | 2.37 | 8.16 | 8.04 (4.54 to 11.66)c | −0.97 (−5.02 to 3.25) | 2006-2011 | 1.00 (−1.94 to 4.03) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2011-2014 | 27.86 (12.04 to 45.91)c | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −0.97 (−5.02 to 3.25) | |

| 6-9 | 2.16 | 4.44 | 0.35 (−2.40 to 3.18) | 0.35 (−2.40 to 3.18) | NAe | NAe |

| 10-14 | 1.68 | 2.24 | 6.35 (3.47 to 9.30)c | −3.74 (−11.09 to 4.22) | 2006-2014 | 6.35 (3.27 to 9.30)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2014-2018 | −3.74 (−11.09 to 4.22) | |

| 15-19 | 1.55 | 1.84 | 3.71 (−1.24 to 8.92) | −6.09 (−13.49 to 1.94) | 2006-2008 | 17.80 (−4.83 to 45.81) |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2008-2016 | −1.44 (−4.21 to 1.41) | |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2016-2018 | −10.53 (−27.72 to 10.74) | |

| 20-24 | 3.33 | 3.08 | 2.82 (0.23 to 5.48)c | −7.48 (−8.62 to −6.32)c | 2006-2009 | 18.36 (10.57 to 26.71)c |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | 2009-2018 | −7.48 (−8.62 to −6.32)c | |

Abbreviations: AAPC, average annual percent change; APC, annual percent change; ER/LA, extended-release, long-acting; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; NA, not applicable.

Joinpoint allowed up to 2 joinpoints. Owing to retail channel data coverage, 2014 was added as a jump point.

Prescription for more than 2 MME/kg/d for persons younger than 15 years and prescription for 90 MME/d or more for persons aged 15 to 24 years.

Annual percent change and AAPC were statistically significant (P < .05) using a 2-sided test based on the permutation methods.

Prescriptions for ER or LA opioid formulations.

No joinpoint detected for these strata and outcomes. APC was constant and equal to AAPC.

Dispensing rates for children aged 6 to 9 years decreased from 4.30 in 2006 to 1.43 in 2018; the largest annual decrease (APC, −20.15%; 95% CI, −24.99% to −14.99%) occurred in 2015-2018 (Table 1). The mean amount dispensed (2006-2018: APC, −2.38; 95% CI, −3.21 to −1.54) and rates of short-duration (2006-2016: APC, −2.20%; 95% CI, −2.68% to −1.72%) and high-dosage (2006-2011: APC, −11.78%; 95% CI, −16.58% to −6.71%) prescriptions decreased, whereas rates of long-duration prescriptions (2011-2018: APC, 7.77%; 95% CI, 4.04% to 11.64%) increased (Table 2, Table 3). The mean prescription duration increased from 7.27 to 9.19 days. During the study period, of all opioids dispensed, short-duration prescriptions decreased from 34.7% to 31.3%, long-duration prescriptions increased from 6.7% to 13.1%, high-dosage prescriptions decreased from 7.0% to 6.6%, and ER/LA prescriptions did not change significantly (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Dispensing rates for children aged 10 to 14 years decreased from 6.63 in 2006 to 2.64 in 2018; the largest annual decrease (APC, −22.24%; 95% CI, −29.32% to −14.45%) occurred in 2016-2018 (Table 1). The mean amount dispensed (2006-2018: APC, −1.26; 95% CI, −1.43 to −1.08) and rates of high-dosage prescriptions (2014-2018: APC, −9.67%; 95% CI, −13.88% to −5.26%) decreased, whereas rates of long-duration (2006-2013: APC, 8.01%; 95% CI, 4.05% to 12.13%) and ER/LA (2006-2014: APC, 6.35%; 95% CI, 3.27% to 9.30%) prescriptions increased (Tables 1-3). The rate of short-duration prescriptions decreased during the study period overall (2006-2016: APC, −2.51%; 95% CI, −2.79% to −2.24%) but increased annually in 2016-2018 (APC, 4.32%; 95% CI, 0.56% to 8.22%). The mean prescription duration increased from 5.91 to 7.38 days, with an initial increase in duration, followed by a decrease in 2014-2018 (APC, −1.97%; 95% CI, −3.64% to −0.26%). During the study period, of all opioids dispensed, short-duration prescriptions decreased from 47.3% to 41.3%, long-duration prescriptions increased from 4.7% to 9.2%, high-dosage prescriptions decreased from 2.7% to 2.0%, and ER/LA prescriptions increased from 1.2% to 2.5% (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Dispensing rates for adolescents aged 15 to 19 years decreased from 19.87 in 2006 to 10.54 in 2018; the largest annual decrease (APC, −13.67%; 95% CI, −18.97% to −8.03%) was in 2015-2018 (Table 1). The mean amount dispensed (2016-2018: APC, −3.83%; 95% CI, −5.05% to −2.61%) and rate of high-dosage prescriptions (2016-2018: APC, −24.06%; 95% CI, −31.81% to −15.42%) decreased, although the rates of ER/LA prescriptions did not change significantly (Table 3). The mean prescription duration was stable (5.11 days in 2006; 5.09 days in 2018), with an initial increase (2006-2016: APC, 1.16%; 95% CI, 0.94% to 1.38%), followed by a decrease in 2016-2018 (APC, −6.72%; 95% CI, −9.29% to −4.07%) (Table 2). During the study period, of all opioids dispensed, short-duration prescriptions decreased from 51.5% to 50.6% (eTable 1 in the Supplement), although the rate increased annually in 2016-2018 (APC, 4.64%; 95% CI, 0.99 to 8.42). Long-duration prescriptions increased slightly from 3.0% to 3.4% of prescriptions, although the rates decreased overall, with an initial increase followed by a greater decrease in 2014-2018.

Dispensing rates for individuals aged 20 to 24 years decreased from 34.81 in 2006 to 15.24 in 2018, with an annual decrease in 2013-2018 (APC, −15.67%; 95% CI, −17.78% to −13.50%) (Table 1). During the study period, the mean amount dispensed (2010-2018: APC, −3.14%; 95% CI, −3.50% to −2.77%) and rates of short-duration (2009-2018: APC, −2.57%; 95% CI, −3.25% to −1.88%) and high-dosage (2016-2018: APC, −20.83%; 95% CI, −29.65% to −10.89%) prescriptions decreased (Tables 1-3). The mean prescription duration decreased from 6.28 to 6.15 days, with an annual increase (2006-2010: APC, 4.35%; 95% CI, 3.36% to 5.34%) followed by a larger decrease in 2016-2018 (APC, −6.54%; 95% CI, −9.30% to −3.70%). During the study period, of all opioids dispensed, short-duration prescriptions were stable at approximately 47% and high-dosage prescriptions decreased from 6.9% to 3.1% (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The proportion of long-duration and ER/LA prescriptions increased, although the rates decreased overall, with an initial increase, followed by a decrease toward the end of the study period.

Similar temporal and age-specific patterns of opioid prescribing were found when prescriptions from certain subspecialty prescribers were removed from the analysis (eTable 3 in the Supplement) and when patients dispensed both a high-dosage and a long-duration prescription were removed from the analysis (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study describes national trends in several important opioid prescribing practices in children, adolescents, and younger adults. Dispensed opioid prescriptions for this population have decreased by 15% annually since 2013. The overall decrease in total opioid prescriptions and rates of dispensing are consistent with prior studies in the pediatric and adult literature and suggest that opioid prescribing practices may be improving.20,21,22,23 Despite this decrease, opioid prescriptions continue to be readily dispensed in all age groups, but most notably to adolescents and younger adults.

The amount dispensed and rates of short-duration and high-dosage prescriptions decreased across all age groups older than 5 years. The greatest decrease in these prescribing practices, as well as a decrease in rates of long-duration prescriptions, was found in adolescents and younger adults. For example, rates of high-dosage prescriptions showed a greater than 20% annual decrease in adolescents and younger adults from 2016 to 2018. Furthermore, rates of ER/LA prescriptions decreased for younger adults. These findings are encouraging in the context of research in adults, which has shown associations between high-dosage, long-duration, and ER/LA prescriptions and opioid use disorder and opioid overdose, and studies showing similar findings among adolescents and younger adults.14,15,16,17,18,19,40 Earlier studies of trends in opioid prescribing among adolescents and younger adults have found stable or decreasing opioid prescribing rates within the past several years and decreases in long-duration prescriptions, although, to our knowledge, no studies have examined trends in high-risk opioid prescribing practices.22,23,24,41 Our findings might reflect changing norms about opioid prescribing, related to policy changes for adults, such as the publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain published in 2016,31 which states that clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose and duration of opioids, as well as state legislation limiting duration and amount of opioid prescribed.25 Opioid prescribing guidelines and efforts focused on deprescribing for adolescents and younger adults at risk for opioid dependence are important strategies to reduce unnecessary prescription opioid use.

In contrast, rates of long-duration prescriptions increased for children and younger adolescents. In particular, children younger than 10 years were dispensed opioids for a longer average duration than were older age groups. Across age groups, the mean prescription duration was always longer than 5 days, which is a risk factor for continuing opioid use long-term in adults.17 In addition, there was a decrease in the rates of short-duration prescriptions for all age groups older than 5 years. These findings are similar to earlier studies in adolescents and the broader population.21,24 Inappropriately long-duration prescriptions could lead to leftover medication in the home and subsequent poisoning in younger children and might increase the risk for nonmedical use of opioids.8,10,11,42

Although dispensing rates decreased significantly for children aged 0 to 5 years, the mean amount of opioids dispensed and rate of high-dosage prescriptions increased. Decreasing trends from 2014 to 2018 suggest a potential change in prescribing practices toward the end of the study period. However, in 2018, 1 in 5 opioid prescriptions for children aged 0 to 5 years was categorized as a high-dosage prescription, indicating that younger children continue to receive large amounts of opioids. A study of children and adolescents prescribed opioids as outpatients found an increased rate of adverse events with higher opioid doses prescribed.9 However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined national trends in the amount of opioids dispensed to children. Younger children are a unique population in which acute and chronic pain management may be challenging owing to difficulties in communication and assessment of pain, which could lead to inappropriate over- or underprescribing.43 In addition, high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions may represent prescriptions for children with chronic illness, for whom these opioid prescribing practices may be appropriate, but our sensitivity analyses found no significant difference in patterns. These findings indicate that trends may not be influenced by this subset of children. However, given the limitations of our database and our findings of differences in prescribing trends by age, future investigation using a database that includes clinical information is warranted to better understand prescribing practices in younger children.

The rates of ER/LA prescriptions have increased for youths younger than 20 years since 2006, with no marked changes toward the end of the study period. In our sensitivity analyses, we found overall lower rates of these prescriptions, but similar trends, which suggests that ER/LA prescriptions may be readily prescribed for patients without chronic pain or illness. When initiating opioid therapy in adults, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend immediate-release opioids for both acute and chronic pain.31 To our knowledge, there have been no studies in children and adolescents examining trends of ER/LA opioid prescriptions; however, one study found an association between ER/LA opioid use and an increased risk of overdose in adolescents and younger adults.18 Therefore, our findings emphasize the need for pediatric guidelines on prescribing and interventions targeted on opioid selection strategies in children. In addition, although we examined ER/LA prescriptions, understanding trends in the type of opioid dispensed is another important area of future study.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the IQVIA LRx database does not contain detailed patient or clinical information, including weights, diagnoses, or indications for prescriptions. We used weight estimates, which have been used in other studies but could lead to inaccuracies in opioid amount and high-dosage opioid calculations.9,19 Without clinical diagnoses, we were limited in our ability to identify patients who may be appropriately prescribed high-dosage or long-duration opioid treatment. However, we performed 2 sensitivity analyses attempting to identify a subset of patients with chronic illness, both of which showed no significant changes in trends. Second, opioids are commonly prescribed to be taken as needed, but the IQVIA LRx database does not contain this information. The database estimates the days’ supply for these prescriptions based on the quantity of opioid dispensed, which could lead to inaccuracies in determining daily dosage and prescription duration. Third, the IQVIA LRx database is a prescription-level database, so we were unable to determine whether a prescription was a refill vs new prescription for a patient. However, we analyzed the number of patients dispensed 1 vs multiple prescriptions each year, with most patients receiving only 1 prescription. Fourth, there is no established definition for high-dosage opioid prescription for children. We created a definition based on maximum dosing by prescribing formularies, but the clinical significance of this value remains unknown. We used 90 MME/d as the level for a high-dosage prescription for adolescents based on the adult studies, although the clinical significance of this dosing in adolescents is not well studied.

Conclusions

From 2006 to 2018, there have been significant decreases in opioid dispensing rates in patients younger than 25 years, with decreased rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions in adolescents and younger adults. However, opioids remain readily dispensed and potential high-risk prescribing practices were common. Given the differences between pediatric and adult pain and indications for opioid prescribing, there is a need for pediatric-specific and adolescent-specific guidelines and focused research in this unique population. Examining trends in opioid prescribing practices is a necessary first step in understanding the scope and direction of the opioid epidemic in this subset of patients. This information may be used to develop national and local targeted interventions.

eTable 1. Annual Opioid Prescribing Practices, 2006-2018, Stratified by Age Groups

eTable 2. Patients <25 Years Old Dispensed One Versus Multiple Opioid Prescriptions, by Year, 2006-2018

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis Removing Oncology, Hematology, and Hospice Prescriber Subspecialties

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis Removing Long-Duration and High-Dosage Prescriptions

References

- 1.Ali B, Fisher DA, Miller TR, et al. Trends in drug poisoning deaths among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2006-2015. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80(2):201-210. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2019 Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States, 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. November 1, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2019-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf

- 3.Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Center for Health Statistics;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaither JR, Shabanova V, Leventhal JM. US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186558. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H IV, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1169-e1177. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):480-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient opioid prescriptions for children and opioid-related adverse events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20172156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen JD, Casavant MJ, Spiller HA, Chounthirath T, Hodges NL, Smith GA. Prescription opioid exposures among children and adolescents in the United States: 2000-2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20163382. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tadros A, Layman SM, Davis SM, Bozeman R, Davidov DM. Emergency department visits by pediatric patients for poisoning by prescription opioids. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(5):550-555. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1194851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195-1201. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovegrove MC, Mathew J, Hampp C, Governale L, Wysowski DK, Budnitz DS. Emergency hospitalizations for unsupervised prescription medication ingestions by young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1009-e1016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, et al. Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):608-615. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, DeVries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):557-564. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use—United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(10):265-269. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6610a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert A. Association of opioid prescribing patterns with prescription opioid overdose in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):141-148. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groenewald CB, Zhou C, Palermo TM, Van Cleve WC. Associations between opioid prescribing patterns and overdose among privately insured adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20184070. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schieber LZ, Guy GP Jr, Seth P, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in opioid prescribing practices by state, United States, 2006-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190665. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagne JJ, He M, Bateman BT. Trends in opioid prescription in children and adolescents in a commercially insured population in the United States, 2004-2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(1):98-99. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudgins JD, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Bourgeois FT. Trends in opioid prescribing for adolescents and young adults in ambulatory care settings. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20181578. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henke RM, Tehrani AB, Ali MM, et al. Opioid prescribing to adolescents in the United States from 2005 to 2016. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(9):1040-1043. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Conference of State Legislatures . Prescribing policies: states confront opioid overdose epidemic. June 30, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescribing-policies-states-confront-opioid-overdose-epidemic.aspx

- 26.Kelley-Quon LI, Kirkpatrick MG, Ricca RL, et al. Guidelines for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents after surgery: an expert panel opinion. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):76-90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.IQVIA Longitudinal Prescription Data (LRx) , 2006-2018. Published 2019. Accessed December 26, 2019. https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/solutions/commercial-operations/essential-information/real-world-data

- 28.Explorer Social. US Census Bureau American community survey 2006-2018: 1-year estimates. 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.socialexplorer.com

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics . Clinical growth charts. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/html_charts/wtage.htm#males

- 30.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control . CDC compilation of benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, stimulants, zolpidem, and opioid analgesics with oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME). 2018. Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html

- 31.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morphine sulfate: pediatric dosing. IBM MicroMedex Drug Info for Apple iOS (version v2376). 2018. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/ibm-micromedex-drug-ref/id666520138

- 33.Morphine (systemic). In: Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs. UpToDate, Inc; 2020. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://online-lexi-com.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/pdh_f/2853079

- 34.Morphine sulfate (pediatric dosing). Epocrates Version 20.11.0. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/epocrates/id281935788

- 35.Hwang CS, Kang EM, Ding Y, et al. Patterns of immediate-release and extended-release opioid analgesic use in the management of chronic pain, 2003-2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180216. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Accessed December 26, 2019. https://www.R-project.org.

- 37.National Cancer Institute . Joinpoint regression program, version 4.8.0.1. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; April 2020.

- 38.Chen HS, Zeichner S, Anderson RN, Espey DK, Kim HJ, Feuer EJ. The Joinpoint-Jump and Joinpoint-Comparability ratio model for trend analysis with applications to coding changes in health statistics. J Off Stat. 2020;36(1):49-62. doi: 10.2478/jos-2020-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomaszewski DM, Arbuckle C, Yang S, Linstead E. Trends in opioid use in pediatric patients in US emergency departments from 2006 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186161. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey JE, Campagna E, Dart RC; RADARS System Poison Center Investigators . The underrecognized toll of prescription opioid abuse on young children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):419-424. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manworren RCB. pediatric pain assessment and indications for opioids. In: Shah RD, Suresh S, eds. Opioid Therapy in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36287-4_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Annual Opioid Prescribing Practices, 2006-2018, Stratified by Age Groups

eTable 2. Patients <25 Years Old Dispensed One Versus Multiple Opioid Prescriptions, by Year, 2006-2018

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis Removing Oncology, Hematology, and Hospice Prescriber Subspecialties

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis Removing Long-Duration and High-Dosage Prescriptions