Abstract

Background

Urinary catheterisation is a common procedure, with approximately 15% to 25% of all people admitted to hospital receiving short‐term (14 days or less) indwelling urethral catheterisation at some point during their care. However, the use of urinary catheters is associated with an increased risk of developing urinary tract infection. Catheter‐associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is one of the most common hospital‐acquired infections. It is estimated that around 20% of hospital‐acquired bacteraemias arise from the urinary tract and are associated with mortality of around 10%.

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2005 and last published in 2007.

Objectives

To assess the effects of strategies for removing short‐term (14 days or less) indwelling catheters in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register, which contains trials identified from CENTRAL, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings (searched 17 March 2020), and reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that evaluated the effectiveness of practices undertaken for the removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters in adults for any reason in any setting.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors performed abstract and full‐text screening of all relevant articles. At least two review authors independently performed risk of bias assessment, data abstraction and GRADE assessment.

Main results

We included 99 trials involving 12,241 participants. We judged the majority of trials to be at low or unclear risk of selection and detection bias, with a high risk of performance bias. We also deemed most trials to be at low risk of attrition and reporting bias. None of the trials reported on quality of life. The majority of participants across the trials had undergone some form of surgical procedure.

Thirteen trials involving 1506 participants compared the removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters at one time of day (early morning removal group between 6 am to 7 am) versus another (late night removal group between 10 pm to midnight). Catheter removal late at night may slightly reduce the risk of requiring recatheterisation compared with early morning (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.96; 10 RCTs, 1920 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain if there is any difference between early morning and late night removal in the risk of developing symptomatic CAUTI (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.63; 1 RCT, 41 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain whether the time of day makes a difference to the risk of dysuria (RR 2.20; 95% CI 0.70 to 6.86; 1 RCT, 170 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

Sixty‐eight trials involving 9247 participants compared shorter versus longer durations of catheterisation. Shorter durations may increase the risk of requiring recatheterisation compared with longer durations (RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.41; 44 trials, 5870 participants; low‐certainty evidence), but probably reduce the risk of symptomatic CAUTI (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.61; 41 RCTs, 5759 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and may reduce the risk of dysuria (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.88; 7 RCTs; 1398 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

Seven trials involving 714 participants compared policies of clamping catheters versus free drainage. There may be little to no difference between clamping and free drainage in terms of the risk of requiring recatheterisation (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.21; 5 RCTs; 569 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain if there is any difference in the risk of symptomatic CAUTI (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.63; 2 RCTs, 267 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or dysuria (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.54; 1 trial, 79 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Three trials involving 402 participants compared the use of prophylactic alpha blockers versus no intervention or placebo. We are uncertain if prophylactic alpha blockers before catheter removal has any effect on the risk of requiring recatheterisation (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.42; 2 RCTs, 184 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or risk of symptomatic CAUTI (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.06; 1 trial, 94 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). None of the included trials investigating prophylactic alpha blockers reported the number of participants with dysuria.

Authors' conclusions

There is some evidence to suggest the removal of indwelling urethral catheters late at night rather than early in the morning may reduce the number of people who require recatheterisation. It appears that catheter removal after shorter compared to longer durations probably reduces the risk of symptomatic CAUTI and may reduce the risk of dysuria. However, it may lead to more people requiring recatheterisation. The other evidence relating to the risk of symptomatic CAUTI and dysuria is too uncertain to allow us to draw any conclusions.

Due to the low certainty of the majority of the evidence presented here, the results of further research are likely to change our findings and to have a further impact on clinical practice. This systematic review has highlighted the need for a standardised set of core outcomes, which should be measured and reported by all future trials comparing strategies for the removal of short‐term urinary catheters. Future trials should also study the effects of short‐term indwelling urethral catheter removal on non‐surgical patients.

Plain language summary

What are the best strategies for removing drainage tubes (urinary catheters) from the urinary bladder after 14 days or less?

Key messages

• Removing drainage tubes late at night instead of early in the morning might reduce the number of people who need to have the drainage tube reinserted.

• Removing drainage tubes sooner rather than later probably reduces the risk of infection caused by the drainage tube and painful urination. However, it may lead to more people needing to have the tube reinserted.

• We need future studies to research the effects of drainage tube removal for people who did not have surgery.

What are urinary catheters?

Urinary catheters are flexible, hollow tubes that are used to empty the urinary bladder and collect urine in a bag. They are often used for short periods of time for people who cannot pass urine themselves, for example during or after surgery, or when healthcare staff need to measure someone’s urine. One harmful effect of catheters is the risk of developing urinary tract infections (UTIs). If catheters are removed quickly, the risk of infection is reduced, but if they are removed too soon, they may need to be reinserted.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to investigate the effects of different strategies on the risk of:

• needing to have the catheter reinserted; • developing a urinary tract infection (UTI); • experiencing pain when urinating.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at the use of short‐term urinary catheters in adults. We defined ‘short‐term’ as 14 days or less. Studies could take place anywhere and participants could have any condition or illness.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 99 studies with 12,241 participants. Most participants were surgical patients and many of the studies (50) assessed women only.

The studies investigated:

• removing the catheter early in the morning compared with late at night (13 studies); • retaining the catheter for shorter or longer times (68 studies); • clamping catheters or allowing them to drain freely (7 studies); and • giving men treatment (alpha blockers) to relax the prostate compared to no treatment before removing the catheter (3 studies). The prostate is a small gland located between the penis and the bladder.

Early‐morning compared to late‐night removal

Late‐night catheter removal might reduce the risk of needing to have the catheter reinserted compared with early‐morning removal. We are uncertain if there is any difference between early‐morning and late‐night removal for developing UTI or painful urination.

Shorter compared to longer use of catheters

People who have their catheters removed after a shorter length of time are probably less likely to develop UTIs and may be less likely to experience painful urination compared with those who have their catheters for longer. However, we also found that people may be more likely to need the catheter reinserting if they have the catheter for a shorter compared with a longer time.

Clamping

There may be little to no difference between clamping and free drainage on the risk of needing the catheter to be reinserted. We are uncertain if there is any difference in the risk of UTIs or painful urination.

Treatment to relax the prostate

We are uncertain whether giving alpha‐blockers before the catheter is removed has any effect on the need to have catheters reinserted or the risk of developing UTIs. There was no evidence about the risk of experiencing painful urination.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Many of the included trials had design flaws, did not recruit enough people, or did not report enough information about their results. This means our confidence in the evidence is limited.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

The evidence is current up to 17 March 2020.

Summary of findings

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2005 and last published in 2007. See Appendix 1 for a glossary of medical terms.

Description of the condition

Catheterisation is an important and common clinical procedure. Approximately 15% to 25% of all people who are hospitalised will be catheterised at some point during their management (CDC 2016). However, it should be noted that not every patient who has a urethral catheter inserted requires one. Trials have shown that it is common for catheters to be placed in patients without an appropriate indication (Loeb 2008; Meddings 2014). Catheterisation could be for the short term (up to 14 days) or long term (14 days or longer). The indications for short‐term catheterisation include monitoring of urine output during the perioperative stage or in acutely unwell patients, as part of a urological procedure, or the treatment of patients with acute urinary retention. Short‐term catheterisation could also be used for investigative purposes, such as imaging of the urinary tract and urodynamic trials (Dunn 2000a). Long‐term catheterisation is usually a last resort option in people with recurrent urinary retention, reduced bladder contractility or urinary incontinence.

Retention of urine has been reported as a common problem following the removal of indwelling urethral catheters, particularly following surgery and anaesthesia, where post‐operative urinary retention has a reported incidence between 5% and 70% (Baldini 2009). The risk factors associated with an increase the risk of developing post‐operative urinary retention have been thoroughly researched and include age (over 50 years), sex (male), type of surgery, duration of surgery, type of anaesthesia (general or regional, e.g. epidural), analgesia (use of opiates) and the amount of intravenous fluids used. Post‐operative urinary retention may lead to urinary tract infections, abnormal autonomic responses (e.g. cardiac arrhythmias) as well as over‐distension of the bladder resulting in permanent detrusor muscle damage (Baldini 2009; Madersbacher 2012; Rosseland 2002; Zaouter 2009). For hospital inpatients, the duration of catheterisation in the peri‐operative period remains controversial and is one that is ultimately down to the preference of the surgeon or anaesthetist responsible for the patient. Removal too early, however, may result in the patient developing urinary retention again and thus risking requiring recatheterisation alongside the complications associated with it (Baldini 2009).

The procedure of indwelling urethral catheterisation is associated with complications such as catheter‐associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), bacteruria, stricture formation, structural damage to the urinary tract, bleeding, cystitis or prostatitis, and patient discomfort (Igawa 2008; Fisher 2017). CAUTI is the most common cause of hospital‐acquired infections with some 70% to 80% of these associated with the use of indwelling urethral catheters (Lo 2014; Nicolle 2014). CAUTI arise from the formation of a biofilm on both the extraluminal and intraluminal portal surfaces of the catheter. This biofilm mainly consists of extraluminal organisms, which adhere to the surfaces of the catheter as soon as it has been inserted. It has the ability to defend microbes from the host's defences as well as antimicrobials (Haque 2018; Nicolle 2014). It is estimated that around 20% of hospital‐acquired bacteraemias arise from the urinary tract and are associated with a mortality of around 10%. The incidence of bacteraemia following a single catheterisation episode has been shown to be as high as 8%, with the duration of catheterisation being the most important risk factor (EAU 2020). Development of symptomatic CAUTI can have serious consequences in some patients and has been shown to increase the length of hospital stay, worsen patient renal function, increase patient mortality and lead to increased costs for healthcare providers. However, with aseptic technique during placement of the catheter, the risk of CAUTI can be reduced (Baldini 2009; EAU 2020; Fisher 2017; Gould 2009; Lo 2014; NICE 2012).

Indwelling urethral catheters are prone to various other complications that prevent effective drainage of urine. The most common non‐infective cause is due to urethral stricture formation. Urethral strictures can develop after repeated urethral catheterisation with long‐term urinary catheter use, as well as after urethral trauma. The most common infective cause is the development of encrustation within the catheter. This is when crystalline compounds (such as calcium phosphate and struvite) precipitate in the alkaline conditions of urine to form solid deposits in the catheter lumen. This process is accelerated in the presence of micro‐organisms such as Proteus mirabilis which resides in the body's own bowel flora. These micro‐organisms produce the enzyme urease, allowing the production of ammonia, which causes further alkalinisation of the urine and catalyses the encrustation process. Catheter encrustation and blockage is thought to be experienced by roughly 50% of patients with long‐term catheters (Stickler 2010). Once a urethral catheter is failing to drain properly, flushing them with saline can often help in trying to relieve the obstruction. However, if this fails it is likely that the urethral catheter will need to be removed and the patient's need for a urinary catheter reassessed (Cravens 2000).

There are two routes of infection through which symptomatic urinary tract infections (UTIs) occur: endogenous and exogenous. Endogenous infections are due to bacteria naturally present in the human body. Typical routes of infection of the urinary tract are rectal, vaginal and meatal (bodily passages). Exogenous sources of infection include contamination by healthcare workers or non‐sterile equipment.

Pathogens typically gain access to the urinary tract either by migrating alongside the exterior surface of the lumen, or by movement alongside the inner lumen of the catheter via contaminated urine collection bags. Thus, maintenance of a sterile, closed urinary drainage system is key to prevent symptomatic CAUTIs. Clinical features of symptomatic UTIs include dysuria, urinary frequency or urgency, haematuria, suprapubic pain or tenderness, loin or flank pain, rigors, fever, altered mental status (e.g. confusion, particularly in the elderly), and nausea and vomiting (CDC 2016; Gould 2009; Grabe 2015; Hollingsworth 2013).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has defined symptomatic CAUTI as a UTI in the presence of an indwelling catheter which is in place for two or more calendar days on the date of the UTI, where day one was the date upon which the catheter was placed; or, the catheter was in place on the date of the UTI or the day before and then removed. The patient’s urine culture (from a mid‐stream or catheter bag sample) must also contain no more than two species of organisms, where one of which has a bacterial colony count of ≥ 105 colony forming unit (cfu)/mL. The CDC criteria for symptomatic UTI must also be met, which states that the patient must also have at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever (> 38 °C); suprapubic tenderness; urinary urgency; increased urinary frequency or dysuria (pain during voiding) (CDC 2016; Gould 2009).

The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) definition differs slightly according to their published guidelines. The IDSA considers symptomatic CAUTI as any UTI associated with a catheter in the presence of clinical features consistent with UTI, with no other identified sources of infection and a bacterial count of ≥ 103 cfu/mL of ≥ 1 bacterial species in a single midstream urine (MSU) or catheter specimen. The IDSA definition of symptomatic CAUTI covers patients with indwelling, intermittent and suprapubic catheters, unlike the CDC definition, which excludes intermittent catheterisation (Hooton 2010).

Patients who do not meet this criterion may still meet the various criteria for asymptomatic bacteraemic urinary tract infections (ABUTI), which is defined by the CDC as people who are asymptomatic but have a urine culture of at least 105 cfu/mL of a bacterial species in their urine sample. Between 75% to 90% of people who have ABUTIs have been shown not to produce a systemic inflammatory response or other indications, which would indicate infection (Gould 2009). The decision on how to monitor and treat these individuals is still undecided and varies amongst health providers. The CDC guidelines on symptomatic CAUTI state that the treatment of ABUTI has not been shown to provide any clinical benefit.

Description of the intervention

For the purpose of this review, we only considered short‐term indwelling urethral catheterisation. We defined short term as an intended duration of urethral catheterisation of 14 days or less. While there is extensive literature on the type, maintenance and techniques for insertion of urinary catheters, limited attention has been given to the policies and procedures for their removal. Although the insertion, removal and management of the catheter are usually undertaken by nurses, decisions about the removal of the catheter often remain with the medical practitioner. While the importance of short‐term urethral catheter management is recognised, there is no consensus among clinicians about the optimal time and method for removal of indwelling urethral catheters. Policies are likely to be based on personal preference and established practices rather than on research evidence (Irani 1995). While clinicians have established policies, there has been no objective and systematic examination of the effect of the time of day the catheter is removed, the length of time the catheter is left in place or if clamping the catheter prior to removal influences patient outcomes.

Indwelling urethral catheters are catheters that are inserted into the bladder, via the urethra, to allow continuous drainage of urine into a closed urine collection system. In some clinical contexts, valves may also be used as an alternative to continuous drainage. The urethral route is most commonly used by health professionals. Other routes of urinary catheterisation include intermittent urethral and suprapubic urinary catheterisation. However, these routes of urinary catheterisation are outwith the scope of this systematic review. Urethral catheterisation usually requires the use of a lubricant gel, which often contains a local anaesthetic, and can be used both in short‐term and long‐term catheterisation. The length of duration of urethral catheterisation is commonly associated with the development of complications, the most common being UTI (Nicolle 2014). Around 60% to 80% of hospitalised patients with indwelling catheters will require antibiotics at some stage of their care, although this is usually for reasons other than UTI (Durojaiye 2015; Foxman 2003). A recent prevalence survey published in The New England Journal of Medicine found that urinary catheters are the most common indwelling device in hospitals, used in 23.6% of patients in 183 hospitals in the USA and roughly 17.5% of patients in 66 European hospitals (Magil 2014).

As a result, the bacteria present in urine are continuously exposed to antimicrobials, thus aiding the development of antimicrobial‐resistant organisms. This rise in antimicrobial‐resistant organisms has proven to be a huge burden for healthcare providers from both an economic and medical standpoint, with many providers struggling to control devastating outbreaks. There is limited evidence for the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in short‐term indwelling urethral catheters (Lusardi 2013).

How the intervention might work

Some investigators have hypothesised the potential advantage of morning or midnight removal of catheters. One argument for the removal of urethral catheters early in the morning is that reduced staff at night might fail to respond to complications, such as urinary retention, that can develop following the removal of the catheter (Blandy 1989; Crowe 1993; Ganta 2005; Kelleher 2002; Webster 2006). Other suggested benefits of removing the catheter early in the morning include allowing the patient to rest through the night and then to adjust back to their normal voiding pattern during the day (Gross 2007).

Researchers have also reported that patients whose catheters were removed in the night had larger volumes at first void compared to other people whose catheters were removed in the morning (Chillington 1992; Noble 1990; Webster 2006). It has been suggested that the timing of catheter removal may affect a patient's length of stay in hospital with consequent resource implications. In one trial it was found that removal of catheters at midnight resulted in patients being discharged a mean of 14 hours earlier than patients whose catheters were removed in the morning (Chillington 1992), thus resulting in economic benefits related to a shorter length of hospitalisation and efficient discharge planning (Kelleher 2002).

There has been some debate about whether flexible policies are better than relatively fixed policies for catheter removal (Wyman 1987). However, practice is known to vary. For example, local clinical audits for catheter removal have indicated that 49% of catheters are removed either at the discretion of the nurse or at the time of the medical rounds and only 34% were removed at midnight (Watt 1998). Of those indwelling urethral catheters that were scheduled for removal in the morning, only 70% were removed on time (Noble 1990; Watt 1998).

Practice also varies with respect to the length of time the catheter is left in situ and the procedure for its removal. The factors that influence this decision include: the condition/reason for which the patient is catheterised; clinician/surgeon preference; patient tolerance; and hospital policy (EAUN 2012). Various international guideline panels agree that indwelling urethral catheters should be removed as soon as they are no longer necessary (CDC 2016; EAU 2020; Grabe 2015; Hooton 2010; NICE 2012). The removal of indwelling urethral catheters after shorter durations may prove to be beneficial, as it has the potential to reduce hospital stays and the number of patients developing symptomatic CAUTIs, thus saving healthcare costs and improving patient outcomes (Baldini 2009; Lo 2014).

Bladder dysfunction and post‐operative voiding impairment has been documented following catheterisation and can lead to infections of the urinary tract. The intermittent clamping of the indwelling urethral catheter draining tube prior to withdrawal has been suggested on the basis that this simulates normal filling and emptying of the bladder (EAUN 2012). While clamping catheters might minimise post‐operative neurogenic urinary dysfunction, it could also result in bladder infection or distension if the clamps are not released as scheduled (Roe 1990; Wang 2016).

Another strategy practised prior to removal of urethral catheters is the use of alpha adrenergic blocker drugs. It is thought that post‐operative urinary retention is potentially linked to the stress‐induced, high sympathetic activity occurring around the peri‐operative period. Counteracting its activity with the inhibition of alpha receptors located in the bladder and urethra may potentially reduce the risk of acute urinary retention (Ghuman 2018; Madani 2014; Patel 2018). It has also been reported that alpha blockers are effective in the treatment of voiding dysfunction by enhancing detrusor contractibility and lowering urethral resistance in patients with underactive bladder (Yamanishi 2004). Thus, prophylactic usage of alpha blockers in people with indwelling urethral catheters could reduce the episodes of developing voiding dysfunction after catheter removal.

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review summarises the evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) related to alternative approaches to the removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters. The findings of this review will help determine the safest method of short‐term catheter removal as well as potentially help reduce the risks associated with catheterisation for patients. Since the last version of this review was published (Griffiths 2007), the evidence base has grown substantially and it is important to incorporate findings from new trials into the review in a manner that will enable clinicians to develop evidence‐based policies for practice.

Objectives

To assess the effects of strategies for removing short‐term (14 days or less) indwelling catheters in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs that evaluated the effects of strategies for removing short‐term indwelling urethral catheters.

For the purposes of this review, we defined 'indwelling catheterisation' in accordance with the European Association of Urology (EAU), which states that it is the passage of a urinary catheter into the bladder via the urethra and held in place by an inflatable balloon (EAU 2020; Grabe 2015; Tenke 2008). We defined as 'short‐term' cases where the intended duration of catheterisation was 14 days or less (Dunn 2000a; Kidd 2015; Lam 2014).

Types of participants

We included trials of adults requiring short‐term indwelling urethral catheterisation in any setting (hospital, community, nursing home) for any reason. These included individuals who were acutely unwell, required surgery, had urinary retention or women during childbirth.

Types of interventions

We included all interventions involving short‐term indwelling urethral catheterisation and made the following comparisons.

Removal of indwelling urethral catheters at one specified time of day (6 am to 7 am) versus another specified time of day (10 pm to midnight)

Shorter durations of indwelling urethral catheterisation versus longer durations of indwelling urethral catheterisation e.g. immediate/early removal versus removal of the indwelling urethral catheter one day post‐surgery

Flexible durations of indwelling urethral catheterisation versus fixed duration of indwelling urethral catheterisation

Clamping of indwelling urethral catheterisation versus free drainage of indwelling urethral catheterisation prior to removal

Prophylactic use of alpha blocker prior to indwelling urethral catheter removal versus no intervention or placebo

We defined early removal of catheters as the removal of an indwelling urethral catheter up to eight hours post‐operatively.

We have not considered the following interventions as they are either covered in separate Cochrane Reviews or do not meet the objectives of this review:

Suprapubic or intermittent urethral catheterisation (Kidd 2015)

Long‐term catheterisation (Cooper 2016)

Differing catheter insertion techniques (e.g. use of aseptic liquid/cream based agents or topical antibiotic creams)

Meatal care management techniques

Types of catheter materials for short‐term catheters (e.g. latex, silicone) (Lam 2014)

Types of catheter coatings for short‐term catheters (e.g. antibiotic coating, silver) (Lam 2014)

Types of drainage container

Treatment of drainage bag with antiseptic/antibiotic

The use of antibiotic prophylaxis as a primary or secondary outcome (Foon 2012; Lusardi 2013)

The use of reminders or protocols for catheter removal, for example, stop‐orders

It should be noted that the use of alpha blockers prior to urethral catheter removal in acute urinary retention (AUR) is covered by another Cochrane Review (Fisher 2014). Our review only looks at the use of prophylactic alpha blockers in short‐term indwelling urethral catheters in instances other than AUR. We excluded trials that looked at the use of antibiotic prophylaxis as a primary or secondary outcome on the basis that this is covered by another Cochrane Review and is not related to the intervention of interest of this review (Lusardi 2013). We did not exclude trials that used antibiotic prophylaxis for both intervention and control groups as part of their hospital policy.

Types of outcome measures

We analysed the following outcomes in this review. It should be noted that we did not use them as a basis for including or excluding trials.

Primary outcomes

Number of participants who required recatheterisation following removal of indwelling urethral catheter

Secondary outcomes

-

Complications/adverse effects

-

Incidence of UTI

symptomatic CAUTI

asymptomatic bacteriuria

Incidence of urinary retention

Other complications of catheterisation (or recatheterisation), for example, haemorrhage, stricture formation, fever

-

-

Patient‐reported

Patient pain or discomfort

Patient satisfaction

Urinary incontinence

Number of patients reporting dysuria

-

Clinician‐reported

Volume of first void (mL)

Time to first void (hours)

Post‐void residual volume (mL)

Length of hospitalisation (days)

Time between removal of catheter to discharge (days)

-

Health status/quality of life

Condition‐specific or generic quality‐of‐life measures (e.g. Short Form 36 (Ware 1992))

Psychological outcome measures (e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983))

Main outcomes for summary of findings tables

Number of participants requiring recatheterisation

Symptomatic CAUTI

Dysuria

Condition‐specific or generic quality‐of‐life measures (e.g. Short Form 36)

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any language or other restrictions on any of the searches described below.

Electronic searches

We identified relevant trials from the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register. For more details of the search methods used to build the Specialised Register, please see the Group's webpages where details of the Register's development (from inception) and the most recent searches performed to populate the Register can be found. The Register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, Be Part of Research and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Many of the trials in the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL.

The date of the last search was: 17 March 2020.

The terms used to search the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register are given in Appendix 2.

For an earlier version of this review update we searched CINAHL (on EBSCO), covering December 1981 to 11 May 2016 (searched on 12 May 2016). For the most recent update of the search (17 March 2020) only the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register was searched, as this now incorporates the CINAHL search. The search strategy used in CINAHL is given in Appendix 3.

The search strategies used to search for the previous version of this review (Griffiths 2007) are given in Appendix 4.

Searching other resources

We also searched the reference lists of all relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

For this update, we used the following methods to assess the new reports that were identified as a result of the updated search. For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Griffiths 2007.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AE and IO) independently screened the titles and abstracts of each trial using Covidence before obtaining the full text for all potentially eligible trials. If the title and abstract were inconclusive, we obtained the full text for further assessment. We attempted to obtain any missing trial data by contacting the trial authors for further information. Duplicate trials that had been reported in more than one publication were included only once. We reached decisions about trial eligibility by a discussion between the author team and resolved any disagreements by consulting an independent third party.

Data extraction and management

Four review authors (AE, FS, EK, IO) extracted data independently using a standardised form and AE compared their results. If the data in trials had not been fully reported, we attempted to contact the trial authors for further classification. We entered the extracted data into Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020).

We have only reported those outcomes that were pre‐specified in the Types of outcome measures. However, there were occasions where the outcomes reported were worded differently despite belonging to the same underlying theme ‐ for example, asymptomatic bacteriuria was also reported as positive urine culture. As these are the same underlying concepts, omitting this information was not appropriate. We therefore chose to collate all data from trials that reported positive urine culture with asymptomatic bacteriuria if they met the CDC definition for asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Four review authors (AE, FS, EK, IO) assessed the included trials for risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed the following domains: random sequence generation (selection bias); allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); blinding of microbiological outcome (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective reporting of outcomes (reporting bias); and other potential sources of bias.

Two of the review authors (AE and one of either IO, FS or EK) independently assessed each of the trials and rated each as 'low risk', 'unclear risk' or 'high risk'. We resolved any difference in opinion by discussion or by consulting an independent third party.

Measures of treatment effect

We processed all trial data as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Li 2021). Where appropriate, we undertook meta‐analysis. We combined outcome data by using a fixed‐effect model to calculate pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). We considered the random‐effects model only when there were concerns about heterogeneity affecting the analysis. For categorical outcomes, we related the numbers reporting an outcome to the numbers at risk in each group to calculate a risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. For continuous variables, we used means and standard deviations to derive the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

In parallel‐group trials, the primary analysis was per participant randomised. Where there were trials that involved a variation of this type of randomisation, for example, cross‐over trials or cluster‐randomised trials, we performed analysis as outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021).

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis where possible, meaning that all participants were analysed according to the group they were randomised in irrespective of whether they received their assigned intervention.

Where participants were excluded after allocation or withdrew from the trial, we reported any details provided in full. If there were data missing, we attempted to contact the original trial authors to obtain the missing trial data. If there was evidence of differential dropout between the groups, the review authors imputed data for the missing results once we had contacted the trial authors. Where trials reported mean values without standard deviations (SDs) but with P values or 95% CI, we used a conversion Excel document designed by a statistician to obtain the SDs. In cases of missing SDs with no P values or 95% CIs, we estimated the SD from another trial in the same meta‐analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We only combined trials if there was evidence that they were clinically similar. We assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots, the Chi² test for heterogeneity and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). If significant heterogeneity existed, we used a random‐effects model. We considered statistical heterogeneity significant if either the P value for the Chi² test was low (P < 0.10) or if the I² statistic suggested heterogeneity. We used the following thresholds for interpreting the I² statistic (Deeks 2021):

0% to 40%: heterogeneity might not be that important

30% to 60%: moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulties associated with the detection and correction of publication bias, as well as various other reporting biases, we employed a comprehensive search strategy involving multiple databases and sources. We assessed the likelihood of any potential publication bias by using funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We combined trials for analysis if the interventions were considered to be clinically similar and used a fixed‐effect approach to carry out meta‐analysis. We considered using a random‐effects model if there was substantial statistical heterogeneity (as judged by the Chi² test or I² statistic).

For illustrative purposes, we displayed data in subgroups in the meta‐analysis to help identify the different types of surgery and catheter durations participants were undergoing.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analyses for the primary outcome for each comparison.

The type of surgery (urological versus non‐urological) that participants underwent is likely to have an impact with regard to infection, dysuria, haemorrhage and stricture formation etc. If a participant was to be admitted for surgery involving the urological tract (e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)), it is likely that the passage of a urethral catheter in these participants would have a potentially worsening impact than those participants with urethral catheters who did not have any urological surgery. This is because the urological tract is likely to have sustained some damage as a result of the trauma involved during the surgery.

The sex of an individual can impact the intervention being studied. Women are more prone to urinary tract infections due to their shorter urethra when compared to the anatomy of men. However, the passage of urethral catheters in women is likely to be less challenging than men. Many men in this review were hospitalised for TURP, implying that passing a urethral catheter is likely to be more technically difficult in men.

Antibiotic prophylaxis: the use of antibiotic prophylaxis for participants with short‐term indwelling urethral catheters is likely to impact outcomes looking at infections (e.g. the number of participants developing symptomatic CAUTI and asymptomatic bacteriuria). Attitudes towards antibiotic prophylaxis in short‐term urethral catheterisation vary, as their use is also associated with an increased risk of developing a hospital‐acquired infection by Clostridium difficile.

Where data were available, we performed post hoc subgroup analysis to assess the impact of prophylactic antibiotics on the number of participants developing symptomatic CAUTI. The use of prophylactic antibiotics is a confounding factor in the number of participants developing CAUTI. We also conducted post hoc subgroup analysis for the outcome of length of hospitalisation to explore the effect of type of surgery as a possible explanation for very high heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis.

For outcomes other than the primary outcome and CAUTI, we used the subgroup function for illustrative purposes only to show the different types of surgery that participants underwent and the different catheter durations. It should be noted that, in these cases, we did not report any results of subgroup analysis in relation to the statistical test for subgroup differences.

Sensitivity analysis

Where data were available, we conducted sensitivity analyses for our primary outcome by excluding trials we judged as high risk of bias for the domains relating to random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared summary of findings tables for our main comparisons and presented the results for the outcomes prespecified in the Types of outcome measures.

We assessed the certainty of the body of evidence using the GRADE approach. When choosing which outcomes to select, we looked at previous Cochrane Reviews involving urethral catheterisation, the review teams for which had conducted group discussions with people who had undergone short‐term indwelling urethral catheterisation to assist with the selection of appropriate outcomes for inclusion in the summary of findings tables (Kidd 2015; Lam 2014; Omar 2013). We classified the primary and secondary outcomes as critical, important or not important from the patients' perspective for decision‐making.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

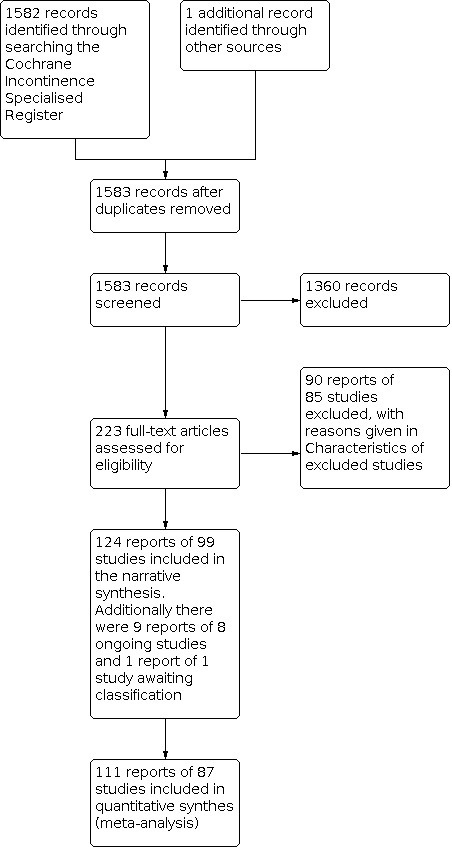

We screened 1583 records, which were identified by the literature search for this review, and retrieved the full texts of 223 reports of trials to assess their eligibility for inclusion. We included 124 reports of 99 trials in this review, and excluded 89 reports of 85 trials from the review. There are nine reports of eight ongoing trials, details of which can be located in the Characteristics of ongoing studies. One trial is still awaiting classification after we obtained further information regarding the trial during the final stages of this review (NCT02602132). Please see the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for more details. The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA diagram (Page 2020; Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Newly included trials

In this update, we re‐assessed the 26 trials included in the previous version of this review and re‐extracted their data (Griffiths 2007). We also evaluated their risk of bias. After performing a new search, we identified a further 73 eligible trials.

Included studies

The trials are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies. We were unable to include 12 trials (13 reports) in the meta‐analysis because they reported data in insufficient detail (Azarkish 2005; Bristoll 1989; Dunn 1999; Dunn 2000b; Iversen Hansen 1984; Nguyen 2012; Ruminjo 2015; Talreja 2016; Wilson 2000; Yee 2015), or they were single trials reporting an outcome for a particular comparison (Liu 2015; Williamson 1982), or reported zero events for a particular outcome and so the result was not estimable (Liu 2015). We contacted the trial authors by email to request further data.

Design

Ninety‐four trials included in the review were RCTs and five trials were quasi‐RCTs (Li 2014; Liu 2015; Noble 1990; Valero Puerta 1998; Zhou 2012).

Sample sizes

The number of participants randomised in the included trials ranged from eight (Williamson 1982), to 501 (Barone 2015). In total, the 99 trials randomised 12,241 participants.

Reason for hospitalisation/catheterisation

The reasons for catheterisation varied between the trials (see Table 5).

1. Types of participants.

| Trial ID | Reason for hospitalisation | Type of surgery/reason for being admitted | Gender |

| Ahmed 2014 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Total abdominal hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy | Female |

| Alessandri 2006 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Vaginal hysterectomy | Female |

| Allen 2016 | Patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery | General thoracic surgical procedure, in whom an epidural catheter was placed for analgesia | Mixed |

| Alonzo‐Sosa 1997 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Anterior colporrhapy, anterior and posterior colporrhaphy with or without vaginal hysterectomy | Female |

| Aref 2020 | Elective CS | Participants admitted for elective CS | Female |

| Aslam 2019 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Participants undergoing minimally invasive pelvic organ prolapse surgery | Female |

| Azarkish 2003 | Elective CS | Participants admitted for elective CS | Female |

| Azarkish 2005 | Emergency CS | Participants admitted for emergency CS | Female |

| Barone 2015 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Participants admitted for vaginal fistula repair | Female |

| Basbug 2020 | Elective CS | Participants admitted for elective CS | Female |

| Benoist 1999 | Elective GI surgery | Extensive rectal resection (total or subtotal proctectomy) | Mixed |

| Bristoll 1989 | Not reported | Not reported | Unknown |

| Carpiniello 1988 | Elective orthopaedic surgery | Total joint replacement (hip or knee) | Female |

| Carter‐Brooks 2018 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Participants undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery | Female |

| Chai 2011 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Total abdominal hysterectomy with or bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy for various benign gynaecological diseases | Female |

| Chen 2013 | Admitted to ICU | Patients requiring mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure | Mixed |

| Chia 2009 | Elective cardiothoracic surgery | Thoracotomy | Mixed |

| Chillington 1992 | Elective urological surgery | TURP | Male |

| Cornia 2003 | Admitted to medicine and cardiology services | Patients admitted to the medicine and cardiology services | Mixed |

| Coyle 2015 | Elective GI surgery | Elective transabdominal colectomy, proctectomy or coloproctectomy | Mixed |

| Crowe 1993 | Admitted to urology ward | Patients admitted to the urology ward with IUCs or who were catheterised during their inpatient stay | Mixed |

| Dunn 1999 | Elective obstetric and gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing elective obstetric or gynaecological surgery | Female |

| Dunn 2000b | Elective gynaecological surgery or CS | Patients undergoing hysterectomy or CS who do not require bladder suspension or strict fluid management | Female |

| Dunn 2003 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Women undergoing hysterectomy for various benign diseases (e.g. fibroid tumours, abnormal uterine bleeding, chronic pain, and persistent cervical dysplasia or micro invasive cancer | Female |

| Durrani 2014 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with bladder outflow obstruction due to benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| El‐Mazny 2014 | Primary or elective CS | Patients admitted to the prenatal wards for primary or repeat elective CS | Female |

| Ganta 2005 | Elective urological surgery | TURP | Male |

| Glavind 2007 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing any type of vaginal prolapse surgery | Female |

| Gong 2017 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer FIGO stage IB‐IIB | Female |

| Gross 2007 | Admitted to stroke ward | Patients with a stroke admitted to the ward | Mixed |

| Gungor 2014 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients with pelvic organ prolapse and/or urinary incontinence undergoing anterior colporrhaphy | Female |

| Guzman 1994 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing vaginal surgery | Female |

| Hakvoort 2004 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing anterior colporrhaphy for vaginal prolapse surgery | Female |

| Hall 1998 | Elective general surgery | Patients admitted to the general surgery wards | Mixed |

| Han 1997 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Hewitt 2001 | Elective urological surgery | Patients requiring radical perineal prostatectomy | Male |

| Huang 2011 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients with cystocele of at least stage II, who were symptomatic and desired operative treatment with anterior vaginal repair with or without other concomitant pelvic surgeries | Female |

| Ind 1993 | Elective hysterectomy, posterior exenteration, colposuspension, anterior colporrhaphy, total/radical vulvectomy, radical oophorectomy, ovarian cystectomy, adhesiolysis myomectomy | Patients which were admitted for any of the following operations: hysterectomy, posterior exenteration, colposuspension, anterior colporrhaphy, total/radical vulvectomy, radical oophorectomy, ovarian cystectomy, adhesiolysis myomectomy | Female |

| Irani 1995 | Elective transurethral prostatic surgery | Patients admitted for transurethral prostatic surgery due to benign hyperplasia | Male |

| Iversen Hansen 1984 | Urethral strictures | Patients with urethral strictures | Not reported |

| Jang 2012 | Surgery for rectal cancer | Patients undergoing elective rectal surgery for cancer | Mixed |

| Jeong 2014 | Robot‐assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy | Patients with localised or advanced prostate cancer | Men |

| Joshi 2014 | Elective hysterectomy with salpingo‐oophorectomy | Patients undergoing uneventful hysterectomy with salpingo‐oophorectomy | Female |

| Jun 2011 | Elective TURP | Patients admitted for TURP | Male |

| Kamilya 2010 | Vaginal prolapse surgery | Patients undergoing vaginal prolapse surgery | Female |

| Kelleher 2002 | Urological surgery | Patients admitted to urology or renal unit | Not reported |

| Kim 2012 | Radical prostatectomy | Patients undergoing extraperitoneal laparoscopic radical prostatectomy | Men |

| Koh 1994 | Elective TURP | Patients admitted for TURP | Men |

| Kokabi 2009 | Anterior colporrhaphy for pelvic organ prolapse | Patients undergoing anterior colporrhaphy due to pelvic organ prolapse and stress incontinence | Female |

| Lang 2020 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for elective benign gynaecological surgery | Female |

| Lau 2004 | Elective general surgery | Patients admitted for elective general surgery | Mixed |

| Li 2014 | Elective TURP | Patients admitted for TURP | Men |

| Liang 2009 | Laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy | Patients admitted for laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy | Female |

| Lista 2020 | Elective urological surgery | Patients admitted for robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy for localised prostate cancer | Male |

| Liu 2015 | Neurosurgery | Patients undergoing neurosurgery | Mixed |

| Lyth 1997 | TURP or bladder neck incision | Patients undergoing TURP or bladder neck incision | Unclear |

| Mao 1994 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing surgery for total hysterectomy or salpingo‐oophorectomy | Female |

| Matsushima 2015 | Surgery for prostate cancer removal (unclear what operation was done) | Patients with prostate cancer | Male |

| McDonald 1999 | TURP | Patients undergoing TURP | Male |

| Naguimbing‐Cuaresma 2007 | Elective CS | Participants admitted for elective CS | Female |

| Nathan 2001 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing surgery for benign gynaecological conditions | Female |

| Nguyen 2012 | Elective urological surgery for urethral strictures | Patients undergoing surgery for urethral strictures | Unclear |

| Nielson 1985 | Elective urological surgery for urethral strictures | Patients undergoing surgery for urethral strictures | Unclear |

| Noble 1990 | Elective urological surgery and procedures | Patients admitted to the urological unit | Mixed |

| Nyman 2010 | Orthopaedic surgery | Patients admitted with hip fractures in need of surgery | Mixed |

| Oberst 1981 | Elective general surgery | Patients undergoing surgery for bowel cancer; low anterior bowel resection or abdominoperineal resection | Mixed |

| Onile 2008 | Elective CS | Patients admitted for elective CS | Female |

| Ouladsahebmadarek 2012 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patienst admitted for elective abdominal hysterectomy or laparotomy for being pathology (fibroma, AUB, chronic pelvic pain, ovarian cysts etc.) | Female |

| Pervaiz 2019 | Elective urological surgery | Patients undergoing TURP | Male |

| Popiel 2017 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing robotic sacrocolpopexy for vaginal prolapse | Female |

| Rajan 2017 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing surgery for Ward Mayo operation; Manchester repair; vaginal hysterectomy and amputation of cervix | Female |

| Ruminjo 2015 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing fistula repair surgery | Female |

| Sahin 2011 | Elective urological surgery | Patients admitted for TURP due to benign prostate hypertrophy | Male |

| Sandberg 2019 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy | Female |

| Schiotz 1995 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for vaginal plastic surgery (anterior colporrhaphy, anterior plus posterior colporrhaphy or a full Manchester repair) | Female |

| Schiotz 1996 | Elective urogynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for elective retro‐pubic surgery for stress incontinence | Female |

| Sekhavat 2008 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing anterior colporrhaphy | Female |

| Shahnaz 2016 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse | Female |

| Shrestha 2013 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for vaginal hysterectomy, anterior colporrhaphy or Manchester operations | Female |

| Souto 2004 | Elective urological surgery | Patients admitted for retropubic radical prostatectomy | Male |

| Sun 2004 | Elective urogynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for Burch's colposuspension | Female |

| Tahmin 2011 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients with genital prolapses admitted for vaginal hysterectomy and or pelvic floor repair | Female |

| Talreja 2016 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Taube 1989 | AUR | Patients admitted to the hospital with AUR | Male |

| Toscano 2001 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Valero Puerta 1998 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Vallabh‐Patel 2020 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients undergoing robotic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse | Female |

| Webster 2006 | General surgery and medical patients | Patients who required IUC on general surgery and medical wards | Mixed |

| Weemhoff 2011 | Elective gynaecological surgery | Patients admitted for anterior colporrhaphy | Female |

| Williamson 1982 | Elective surgery (unspecific) | Patients undergoing surgery (not specified by trial) | Female |

| Wilson 2000 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Wu 2015 | Elective gallbladder or biliary tree surgery | Pateints undergoing gallbladder or biliary tree surgery | Mixed |

| Wyman 1987 | Elective urological surgery | Patients with benign prostatic enlargement undergoing TURP | Male |

| Yaghmaei 2017 | Elective CS | Patients who underwent CS | Female |

| Yee 2015 | Elective CS | Patients who underwent CS under spinal anaesthesia | Female |

| Zaouter 2009 | Elective major abdominal and thoracic surgery | Patients admitted for elective major abdominal and thoracic surgery | Mixed |

| Zhou 2012 | Elective CS | Patients who underwent CS | Female |

| Zmora 2010 | Elective colon and rectal surgery with pelvic dissection | Patients admitted for elective colon and rectal surgery | Mixed |

| Zomorrodi 2018 | Elective renal transplant surgery | Patients with end‐stage renal failure undergoing renal transplant surgery | Mixed |

AUB: abnormal uterine bleeding; AUR: acute urinary retention; CS: cesarean section; GI: gastrointestinal; FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; ICU: intensive care unit; IUC: indwelling urethral catheter; TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate

Urological or urogenital surgery (Chillington 1992; Durrani 2014; Ganta 2005; Han 1997; Hewitt 2001; Irani 1995; Jeong 2014; Jun 2011; Kelleher 2002; Kim 2012; Koh 1994; Li 2014; Lista 2020; Lyth 1997; Matsushima 2015; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Pervaiz 2019; Sahin 2011; Souto 2004; Talreja 2016; Toscano 2001; Valero Puerta 1998; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987)

Urethrotomy and urethral strictures (Iversen Hansen 1984; Nguyen 2012; Nielson 1985)

Obstetric and gynaecological surgery (Ahmed 2014; Alessandri 2006; Alonzo‐Sosa 1997; Aref 2020; Aslam 2019; Azarkish 2003; Azarkish 2005; Barone 2015; Basbug 2020; Carter‐Brooks 2018; Chai 2011; Dunn 1999; Dunn 2000b; Dunn 2003; El‐Mazny 2014; Glavind 2007; Gong 2017; Gungor 2014; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Huang 2011; Ind 1993; Joshi 2014; Kamilya 2010; Kokabi 2009; Lang 2020; Liang 2009; Mao 1994; Naguimbing‐Cuaresma 2007; Onile 2008; Ouladsahebmadarek 2012; Popiel 2017; Rajan 2017; Ruminjo 2015; Nathan 2001; Sandberg 2019; Schiotz 1995; Schiotz 1996; Sekhavat 2008; Shahnaz 2016; Shrestha 2013; Sun 2004; Tahmin 2011; Vallabh‐Patel 2020; Weemhoff 2011; Yaghmaei 2017; Yee 2015

Management of acute urinary retention (Lau 2004; Taube 1989; Wu 2015)

Major abdominal or thoracic surgery, or both (Allen 2016; Chia 2009; Zaouter 2009)

Colon or rectal surgery (Benoist 1999; Coyle 2015; Jang 2012; Lau 2004; Oberst 1981; Zmora 2010)

Women undergoing any surgery (Williamson 1982)

Stroke (Gross 2007)

Orthopaedic surgery (Carpiniello 1988; Nyman 2010)

Urology ward (Crowe 1993)

Intensive care unit (Chen 2013; Zomorrodi 2018)

Medicine and cardiology patients (Cornia 2003)

General medical or surgery ward (Hall 1998; Webster 2006)

Neurosurgery (Liu 2015)

Sex

Fifty trials included women only (Ahmed 2014; Alessandri 2006; Alonzo‐Sosa 1997; Aref 2020; Aslam 2019; Azarkish 2003; Azarkish 2005; Barone 2015; Basbug 2020; Carpiniello 1988; Carter‐Brooks 2018; Chai 2011; Dunn 1999; Dunn 2000b; Dunn 2003; El‐Mazny 2014; Glavind 2007; Gong 2017; Gungor 2014; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Huang 2011; Ind 1993; Joshi 2014; Kamilya 2010; Kokabi 2009; Lang 2020; Liang 2009; Mao 1994; Naguimbing‐Cuaresma 2007; Nathan 2001; Onile 2008; Ouladsahebmadarek 2012; Popiel 2017; Rajan 2017; Ruminjo 2015; Sandberg 2019; Schiotz 1995; Schiotz 1996; Sekhavat 2008; Shahnaz 2016; Shrestha 2013; Sun 2004; Tahmin 2011; Vallabh‐Patel 2020; Weemhoff 2011; Williamson 1982; Yaghmaei 2017; Yee 2015; Zhou 2012).

Twenty‐two trials included men only (Chillington 1992; Durrani 2014; Ganta 2005; Han 1997; Hewitt 2001; Irani 1995; Jeong 2014; Kim 2012; Koh 1994; Li 2014; Lista 2020; Matsushima 2015; McDonald 1999; Pervaiz 2019; Sahin 2011; Souto 2004; Talreja 2016; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001; Valero Puerta 1998; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987).

Twenty‐one trials included participants of both sexes (Allen 2016; Benoist 1999; Chen 2013; Chia 2009; Cornia 2003; Coyle 2015; Crowe 1993; Gross 2007; Hall 1998; Jang 2012; Jun 2011; Lau 2004; Liu 2015; Noble 1990; Nyman 2010; Oberst 1981; Webster 2006; Wu 2015; Zaouter 2009; Zmora 2010; Zomorrodi 2018).

Six trials did not report participants' sex (Bristoll 1989; Iversen Hansen 1984; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; Nguyen 2012; Nielson 1985).

Age

A wide range of ages was reported in the included trials (see Table 6). Twenty‐three trials did not report the age of participants (Aslam 2019; Azarkish 2005; Bristoll 1989; Chillington 1992; Cornia 2003; Crowe 1993; Dunn 1999; Dunn 2000b; Dunn 2003; Hall 1998; Hewitt 2001; Kelleher 2002; Kim 2012; Kokabi 2009; Lyth 1997; Mao 1994; Naguimbing‐Cuaresma 2007; Nguyen 2012; Noble 1990; Popiel 2017; Ruminjo 2015; Wilson 2000; Yee 2015). In trials that did report age of participants, reported it for each trial arm, overall or both.

2. Interventions and age of participants.

| TrialID | InterventionA | Intervention B |

Age (A), years Mean (SD) |

Age (B), years Mean (SD) |

Age (overall), years |

| Ahmed 2014 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 24 h post‐op | 59.1(8.3) | 61.3 (10.5) | Not reported |

| Alessandri 2006 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 12 h post‐op | 51 (4.3) | 47 (5) | Not reported |

| Allen 2016 | IUC removed within 48 h post‐op | IUC removed within 6 h after epidural removal | 61.1 (range 31–85) | 61.7 (range 21–87) | 61.5 (range 21‐87) |

| Alonzo‐Sosa 1997 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | 53.5 (range 37‐63) | 47.1 (range 37‐67) | Not reported |

| Aref 2020 | IUC removal 6 h post‐op | IUC removal 24 h post‐op | 25.3 (2) | 25.6 (3) | Not reported |

| Aslam 2019 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1‐day post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Azarkish 2003 | IUC removal 2‐3 h after surgery | IUC removal the morning after surgery | 24.96 (4.88) | 27.06 (5.56) | Not reported |

| Azarkish 2005 | IUC removal 2‐3 h after surgery | IUC removal 24 h after surgery | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Barone 2015 | IUC removal 7 days after surgery | IUC removal 14 days after surgery | 31.9 (11.5) | 30.6 (11.7) |

Not reported |

| Basbug 2020 | IUC removal 2 h after surgery | IUC removal 12 h after surgery | 30.13 (5.83) | 29.96 (4.71) | Not reported |

| Benoist 1999 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 5 days post‐op | 55 (18) | 56 (17) | Not reported |

| Bristoll 1989 | threshold clamping | complete drainage | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Carpiniello 1988 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1‐day post‐op | 73 (6.6) | 70 (8.6) | Not reported |

| Carter‐Brooks 2018 | IUC removal 4 h after surgery | IUC removal 6 am on post‐op day 1 | 64.9 (11.5) | 65.2 (10.3) | Not reported |

| Chai 2011 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | 46.4 (3.9) | 46.4 (4.0) | Not reported |

| Chen 2013 | IUC removal ≤ 7 days | IUC removal > 7 days | 77 (12.7) | 78 (10.5) | Not reported |

| Chia 2009 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | 54.7 (11.2) | 55.7 (10.3) | Not reported |

| Chillington 1992 | IUC removal at midnight | IUC removal at 6 am the next morning | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cornia 2003 | A computer study order was used to remind staff to remove the IUC after 3 days | A computer study order was not used to remind staff to remove the IUC after 3 days | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Coyle 2015 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal within 12 h of withdrawal of epidural anaesthesia | 63.5 (SD not reported) | 62 (SD not reported) | Not reported |

| Crowe 1993 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dunn 1999 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | Delayed IUC removal post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dunn 2000b | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dunn 2003 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Durrani 2014 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 4 or 5 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 71.32 (5.94) |

| El‐Mazny 2014 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 12 h post‐op | 24.5 (4.2) | 23.8 (3.9) | Not Reported |

| Ganta 2005 | IUC removal at midnight | IUC removal at 6 am | 69.9 (SD not reported) | 68.2 (SD not reported) | 68.9 (SD not reported) |

| Glavind 2007 | IUC removal 3 h post‐op | IUC removal the next morning | Not reported | Not reported | 61 (range 31‐88) |

| Gong 2017 | IUC for 48 h with intermittent clamping | IUC for 48 h without intermittent clamping | 46.14 (8.33) | 45.70 (9.63) | Not Reported |

| Gross 2007 | IUC removal at 10 pm the day the order for removal was written | IUC removal at 7 am the day after the order for removal was written | Not reported | Not reported | 70.3 (11.7) |

| Gungor 2014 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 3 or 4 days post‐op | 55.7 (8.8) | 3 days: 58.5 (10.1) 4 days: 55.8 (9.0) |

Not reported |

| Guzman 1994 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op (with and without bladder‐clamping) | 56 (range 40‐75) | No clamping: 58 (range 8‐79) Clamping: 57 (range 36‐75) |

Not reported |

| Hakvoort 2004 | IUC removal on the morning after surgery | IUC removal 5 days post‐op | 67 (range 36 ‐ 86) | 66 (range 33‐87) | Not reported |

| Hall 1998 | IUC removal between 7 am and 9 am | IUC removal between 9 pm and 11 pm | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Han 1997 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal ≥ 3 days post‐op | 64.6 (range 50‐86) | 68.2 (range 50‐90) | Not reported |

| Hewitt 2001 | IUC removal 4‐6 days post‐op | IUC removal at 14 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Huang 2011 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 3 or 4 days post‐op | 61.21, (10.17) | 3 days: 63.93 (10.43) 4 days: 63.7 (12.5) |

62.9 (10.93) |

| Ind 1993 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | 49.59 (14.2) | 49.84 (16.6) | Not reported |

| Irani 1995 | IUC removal within 48 h | IUC removal at surgeon's discretion | 70.7 (range 42‐88) | 70 (range 58‐85) | Not reported |

| Iversen Hansen 1984 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 14 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 70 (range 24‐85) |

| Jang 2012 | No alpha blockers given | Prophylactic alpha blockers given | 54 (range 48‐62) | 59 (range 54‐66) | Not reported |

| Jeong 2014 | Prophylactic alpha blockers given | No alpha blockers given | 63.6 (6.6) | 63.4 (8) | Not reported |

| Joshi 2014 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | 46.8 (6.9) | 45.09 (6.44) | Not reported |

| Jun 2011 | Prophylactic alpha blockers given | No alpha blockers given | 68.71 (7.6) | 71.4 (7.85) | Not reported |

| Kamilya 2010 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 4 days post‐op | 46.9 (12.02) | 47.9 (12.78) | Not reported |

| Kelleher 2002 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kim 2012 | IUC removal on post‐op day 3/4 | IUC removal on post‐op day 7/8 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Koh 1994 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | 68.8, 7.3 (mean, SD) | 73, 7.6 (mean, SD) | Not reported |

| Kokabi 2009 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 2 days post‐op OR 4 days post‐op (3‐arm trial) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lang 2020 | IUC removal 4 h post‐op | IUC removal day 1 post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 44.4 (8.8) |

| Lau 2004 | "In out" catheterisation | IUC overnight | Not reported | Not reported | 63.3 (4.9) |

| Li 2014 | IUC removal on day 1‐2 post‐op | IUC removal on day 5‐7 post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Range 56 ‐ 92 |

| Liang 2009 | IUC removal immediately | IUC removal 1 day post‐op OR 2 days post‐op (3‐arm trial) |

43.7 (3.9) | B) 45.7 ( 3.5) C) 45.7 ( 5.8) |

Not reported |

| Lista 2020 | IUC removal on day 3 post‐op | IUC removal on day 5 post‐op | 63 (range 48 ‐ 75) | 64 (range 45 – 75) | Not reported |

| Liu 2015 | Clamping of IUC | No clamping of IUC i.e. free drainage | 51 (13.2) | 52 (16.4 SD) | Not reported |

| Lyth 1997 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mao 1994 | IUC duration 7 am to 8 pm (same day) | IUC duration 7 am to 6 am (next day) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Matsushima 2015 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 4 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 65.9 (5.5) |

| McDonald 1999 | IUC removal at midnight | IUC removal at 6 am | 66.7 (range 51‐81) | 68.7 (range 57‐89) | 67.8 (range 51‐89) |

| Naguimbing‐Cuaresma 2007 | IUC removal 4 h post‐op | IUC removal day 1 post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nathan 2001 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | 46.5 (5.6) | 45.7 (5.4) | Not reported |

| Nguyen 2012 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 10 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nielson 1985 | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | IUC removal 28 days post‐op | 64 (range 21‐81) | 64 (range 16‐78) | Not reported |

| Noble 1990 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at midnight | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nyman 2010 | Clamping of IUC | No clamping of IUC | 79 (11) | 80 (11.2) | Not reported |

| Oberst 1981 | Clamping of IUC | No clamping of IUC | 64.5 (10.26) | 59 (11.92) | Not reported |

| Onile 2008 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removed immediately post‐op | 31.67 (6.042) | 32.72 (5.96) | Not reported |

| Ouladsahebmadarek 2012 | IUC removed immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | 37.48 (8.85) | 39.48 (9.54) | Not reported |

| Pervaiz 2019 | IUC removal on day 1 post‐op | IUC removal on day 4 post‐op | 67.00 (9.11) | 65.56 (9.25) | Not reported |

| Popiel 2017 | IUC removal within 6 h of operation completion | IUC removal on day 1 post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Rajan 2017 | IUC removal within 3 h of operation completion | IUC removal on day 1 post‐op | 50 (18) | 48 (2.4) | Not reported |

| Ruminjo 2015 | IUC removal on day 7 post‐op | IUC removal on day 14 post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Sahin 2011 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 2 days post‐op AND 3 days post‐op (3‐arm trial) |

62.5 (SD not reported) | B: 61.5, C: 62 (SD not reported) | 62 (range 48‐77) |

| Sandberg 2019 | IUC removal immediately post‐op | IUC removal 18‐24 h post‐op | 49.3 (10.5) | 51.5 (11.9) | Not reported |

| Schiotz 1995 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 65.9 (range 29.9‐95.2) |

| Schiotz 1996 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 50.3 (range 26.9‐72.6) |

| Sekhavat 2008 | IUC removed immediately post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | 38.9 (2.9) | 39 (3.8) | Not reported |

| Shahnaz 2016 | IUC removal 24 h post‐op | IUC removal 72 h post‐op | 39.4 (3.2) | 38.8 (2.8) | Not reported |

| Shrestha 2013 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | 53.35 (10.94) |

| Souto 2004 | IUC removal 7 days post‐op | IUC removal 14 days post‐op | 64 (7.3) | 61 (7.3) | 62 (range 50‐73) |

| Sun 2004 | IUC removal on the next morning post‐op | IUC removal 5 days post‐op | 46.7 (6.7) | 48.3 (8.3) | Not reported |

| Tahmin 2011 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 5 days post‐op | 51.75 (10.8) | 53.95 (12.8) | Not reported |

| Talreja 2016 | Clamping of IUC | No clamping of IUC i.e. free drainage | 63.05 (4.69) | 64.21 (5.36) | Not reported |

| Taube 1989 | IUC removal immediately after emptying of bladder | IUC removal 1 day post‐op AND 2 days post‐op (3‐arm trial) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Toscano 2001 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Valero Puerta 1998 | IUC removal on day 2 post‐op | IUC removal according to usual care | 70 (range 53‐83) | 69 (range 50‐87) | Not reported |

| Vallabh‐Patel 2020 | IUC removal 6 h post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | 59.52 (8.5) | 59.57 (11.2) | Not reported |

| Webster 2006 | IUC removal at 6 am | IUC removal at 10 pm | 55.02 (19.97) | 55.05 (18.99) | Not reported |

| Weemhoff 2011 | IUC removal 2 days post‐op | IUC removal 5 days post‐op | 59.9 (10.2) | 60.7 (11.1) | Not reported |

| Williamson 1982 | Clamping of IUC | No clamping of IUC i.e. free drainage | Not reported | Not reported | Range 22‐40 |

| Wilson 2000 | Bladder infusion with normal saline by gravity until bladder was full | IUC removal at 6 am | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Wu 2015 | Catheter clamped when patient woke up post‐op. On Day 1 morning post‐op, when the patient felt urge to pass urine, the urinary catheter balloon was deflated and the catheter allowed to be self‐dislodged during urination | On the morning of Day1 post‐op, after the patient passed urine (through the catheter), saline was used to wash the bladder and the catheter clamped. 10 min after clamping, the balloon was deflated and the catheter allowed to be self‐dislodged during urination | 45.6 (7.2) | 46.1 (7) | Not reported |

| Wyman 1987 | IUC removal between 6 am and 7 am | IUC removal between 10 pm and 11 pm | Not reported | Not reported | 70.8 (range 50‐89) |

| Yaghmaei 2017 | IUC removal 6 h post‐op | IUC removal 12‐24 h post‐op | 28.19 (5.80) | 28.01 (5.83) | Not reported |

| Yee 2015 | IUC removal 8 h post‐op | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zaouter 2009 | IUC removal on the same morning as the surgery | IUC removal when the epidural anaesthesia was removed | 57 (15) | 63 (11) | Not reported |

| Zhou 2012 | IUC removal 6‐8 h post‐op | IUC removal 24 h post‐op | 25.11(4.88) | 26.33 (5.08) | Not reported |

| Zmora 2010 | IUC removal 1 day post‐op | IUC removal 3 days post‐op AND 5 days post‐op (3‐arm trial) |

57.4 (range 18‐85) | B: 54.6 (range 25‐81) C: 54.2 (range 22‐78) |

Not reported |

| Zomorrodi 2018 | IUC removal 3 days post‐op | IUC removal 7 days post‐op | 43.52 (13.6) | 43.20 (14.39) | Not reported |

IUC: indwelling urethral catheter

In eight trials participants were less than 35 years old (Aref 2020; Azarkish 2003; Barone 2015; Basbug 2020; El‐Mazny 2014; Onile 2008; Yaghmaei 2017; Zhou 2012). In 49 trials, participants were 35 to 65 years old (Ahmed 2014; Alessandri 2006; Allen 2016; Alonzo‐Sosa 1997; Benoist 1999; Carter‐Brooks 2018; Chai 2011; Chia 2009; Coyle 2015; Dunn 2003; Glavind 2007; Gong 2017; Gungor 2014; Guzman 1994; Huang 2011; Ind 1993; Jang 2012; Jeong 2014; Joshi 2014; Kamilya 2010; Lang 2020; Lau 2004; Liang 2009; Lista 2020; Liu 2015; Nathan 2001; Nielson 1985; Oberst 1981; Ouladsahebmadarek 2012; Rajan 2017; Sahin 2011; Sandberg 2019; Schiotz 1996; Sekhavat 2008; Shahnaz 2016; Shrestha 2013; Souto 2004; Sun 2004; Tahmin 2011; Talreja 2016; Valero Puerta 1998; Vallabh‐Patel 2020; Webster 2006; Weemhoff 2011; Williamson 1982; Wu 2015; Zaouter 2009; Zmora 2010; Zomorrodi 2018). Nineteen trials had participants between 65 to 75 years old (Carpiniello 1988; Chen 2013; Durrani 2014; Ganta 2005; Gross 2007; Hakvoort 2004; Han 1997; Irani 1995; Iversen Hansen 1984; Jun 2011; Koh 1994; Li 2014; Matsushima 2015; McDonald 1999; Pervaiz 2019; Schiotz 1995; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001; Wyman 1987). The participants of one trial were more than 75 years old (Nyman 2010).

Participants who received antibiotics during hospitalisation

There was considerable variation between trials in participants receiving antibiotic prophylactic therapy (see Table 7). We think this is most likely due to the reasons for hospitalisation.

3. Use of antibiotic prophylaxis.

| TrialID | Comparison | Antibiotic prophylaxis used | Details |

| Ahmed 2014; | 2 | Yes | Prophylaxis was given to all patients on the morning of surgery in the form of 1 g of ceftriaxone IM |

| Alessandri 2006 | 2 | Yes | Prophylaxis was given as a single dose before operation |

| Allen 2016 | 2 | No | N/A |

| Alonzo‐Sosa 1997 | 2 | No | N/A |

| Aref 2020 | 2 | Yes | Single dose of prophylactic antibiotic in the form of ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Aslam 2019 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Azarkish 2003 | 2 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Azarkish 2005 | 2 | Not reported | Perineum wash by povidone iodine 10% before catheter insertion |

| Barone 2015 | 2 | No | N/A |

| Basbug 2020 | 2 | Yes | All participants received 1 g IV cefazolin as prophylaxis |

| Benoist 1999 | 2 | Yes | All participants received IV antibiotics as a single dose at the induction of anaesthesia |

| Bristoll 1989 | 3 | Not reported | N/A |

| Carpiniello 1988 | 2 | Yes | Prophylactic cefazolin sodium or clindamycin was given on post‐op day 3 |

| Carter‐Brooks 2018 | 2 | Not reported | N/A |

| Chai 2011 | 2 | No | N/A |

| Chen 2013 | 2 | No | Routine prophylaxis was not given. Antibiotics were only used in symptomatic participants. |

| Chia 2009 | 2 | Yes | Single dose of prophylactic antibiotic was given IV in all participants |

| Chillington 1992 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported |